Abstract

This study aimed to assess the knowledge regarding impacts, causes and management of black triangles (BT) among participants from different educational backgrounds including dental students, dentists and laypeople. This descriptive cross-sectional observational research included 435 participants who comprised 4 groups: pre-clinical (3rd year) dental students, clinical (4th and 5th year) dental students, dentists, and laypeople. A constructed self-reported questionnaire was utilized to assess participants’ demographic data and their knowledge of the impacts, causes and management of BT. The VAS scale was used to assess participants’ ratings for the impacts of BT on esthetics, with 0 meaning no impact and 10 meaning very severe negative impacts. The most reported treatments for BT were “cannot be treated” 99.3% and “non-surgical periodontal treatment” 67.1%. Meanwhile, the least reported was “modify the porcelain” 41.8%. The most reported cause of BT was “periodontal disease” 85.1%. However, the least reported were “parafunction” and “deep implants” 33.1% each. Dental professionals had better knowledge of the causes (t = 8.189, P < 0.001) and management (t = 8.289, P < 0.001) of BT than the non-dental participants. The dentists had the best knowledge, while the laypeople had the least knowledge of the causes (F = 62.056, P < 0.001) and treatment (F = 46.120, P < 0.001) of BT. The knowledge of the causes (t = 0.616, P = 0.538) and treatment (t = 1.113, P = 0.266) for BT was not significantly different between males and females. Age was not significantly related to the total knowledge about the causes (r = −0.034, P = 0.475) or treatment (r = −0.034, P = 0.482) for BT. Dental professionals had better knowledge of the impacts, causes and management of BT than the non-dental participants. The dentists were the best, while the laypeople were the worst in this regard. Age and gender had no relationships with the knowledge of causes or management of BT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The loss of interdental gingival papillary tissue results in the formation of a triangular space between the dentition known as open gingival embrasures or black triangles1,2,3,4. This might result in esthetic troubles, speech problems, food impaction and/or improper plaque control5,6,7. Black triangles, especially between the central incisors, are considered among the worst esthetic factors that negatively impact smile esthetics8,9,10,11,12.

The loss of support for interdental papillae is multifactorial, and would result from the loss of tooth contact, loss of bone, or increased distance from tooth contact point to the bony crest that is caused by several reasons, including periodontal disease, periodontal surgery, traumatic insults, improper tooth surface contours, aging, tooth spacing and loss of teeth5,13,14. Also, orthodontic treatment15 and implant restorations are associated with higher chances of papillary loss16,17,18.

Currently, management of black triangles includes prosthetic14,19,20, orthodontic21, and surgical approaches22,23 as well as tissue regeneration24 and tissue volumising25. Considering the difficulty in regenerating the interdental papillary tissue26, it is important to prevent black triangles by having enough support for the interdental papilla and not exceeding certain dimensions between the contact of teeth and the alveolar bone crest5. This is challenging as regeneration of lost tissue is difficult and requires maintaining the interdental papillary tissue volume within certain and difficult to obtain circumstances8,26. Also, having long interdental contact was preferred by patients as opposed to the presence of black triangles8.

Perception of esthetics is a complicated dynamic phenomenon affected by multiple dimensions including geographic, demographic (gender, age and education), socio-cultural and psychological factors27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. Furthermore, previous research demonstrated significant differences between patients’ and dentists’ opinions regarding face and smile esthetics35,36.

Hence, dental professionals were found to be more critical in their judgment of dental and smile esthetics than laypeople12,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44, and this might owe to their dental education31. In addition, dental specialists perceive the black triangle as less attractive than non-specialists or laypeople28,37,39. Moreover, younger patients and females perceive black triangles as less attractive than males and older patients45,46. Nevertheless, laypeople and periodontists were found to consider the inflamed gingiva as worse than black triangles12.

This potentially inspired investigators to better understand how to prevent and manage black triangles. In fact, a successful treatment would probably result when the goals and expectations of the patient and the clinician overlap12,47. This may help in directing the appropriate treatment to the patient and by this, save time, efforts, and costs29,30,33,34.

The literature lacks studies that investigate the knowledge of participants concerning the causes and management of black triangles. In addition, the literature lacks studies that explore the knowledge among different study groups including dentists, clinical dental students, preclinical dental students and laypeople. Furthermore, the literature is short in studies concerning the associations between knowledge regarding black triangles and age and gender.

Consequently, this study was conducted to explore the knowledge regarding the impacts, causes and management of black triangles among participants from different educational backgrounds. This could add further guidance to better understand the factors involved in the perception and management of black triangles.

The aim of the current study was to identify the knowledge regarding the impacts, causes and management of black triangles, and the relationship between the knowledge and the educational background among preclinical dental students, clinical dental students, dentists and laypeople.

The null hypothesis for this study was that there is no difference in the knowledge regarding the impacts, causes and management of black triangles between preclinical dental students, clinical dental students, dentists and laypeople.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

This descriptive cross-sectional, observational investigation was conducted between June 2022 and October 2022 in the University of Jordan considering the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration (9th version, 2013). It was ethically approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Jordan (Reference number: 19-2022-238 dated 17-4-2022). A signed written informed consent was provided by each participant before inclusion in the study.

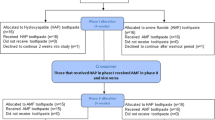

The participants were invited to participate and were recruited from their laboratories (3rd year pre-clinical dental students), clinics (4th and 5th year dental students), offices (employees) and practices (dentists).

Simple randomization utilizing computer generated numbers was used to select the place (laboratories, clinics, offices and practices) of recruitment. A non-probability, convenient, and purposive sampling was used to recruit the participants in this study.

The invitation to participate in this study was extended to 450 participants, and 435 accepted to participate and were recruited (response rate = 96.7%). The study sample consisted of 4 groups including 3rd year preclinical dental students, 4th and 5th year clinical dental students, dentists and laypeople.

The participants were included if they were able to comprehend the questionnaire, did not have debilitating disease or mental disorders and were able to provide a signed informed consent. Also, dentists were included if they are currently practicing dentistry and registered with the Jordan Dental Association.

Dentists were excluded if they were not practicing or not registered with the Jordan Dental Association. Also, participants with history of mental disorders or debilitating disease were excluded.

Study instruments and procedures

After recruitment, the participants were requested to complete a constructed self-reported questionnaire. The questionnaire was adopted from Atieh (2023)48. The questionnaire was developed, used, and validated in a previous investigation48. The development of the questionnaire involved reviewing the relevant literature and drafting the available causes, impacts and management of black triangles. Then, a panel of dental professionals with previous experience with black triangles (4 prosthodontists, 2 periodontists, 2 orthodontists, 1 oral surgeon, and 2 general dental practitioners) was consulted regarding the developed and drafted causes, impacts and management of black triangles. They were requested to comment on the clarity of the drafted questionnaire as well as to add any missing causes, impacts and managements of black triangles. Following the feedback of the consulted dental professionals, a final draft was prepared and sent back to the consulted professionals for final suggestions. Then, the used questionnaire was finalized. After development, the questionnaire was used and validated in a previous investigation that started with a pilot study, which validated and tested the questionnaire for clarity and effectiveness48. In addition, the test–retest reliability was conducted by Atieh (2023)48 as well as during this investigation to indicate the reliability of the used questionnaire.

To assess the reliability of participants’ responses to the questions, forty participants (ten from each group) were asked to answer the questions twice with a one week interval between the two occasions. In this regard, the Kappa value ranged between 0.8 and 0.9 for the tested questions, indicating an adequate reliability.

The utilized questionnaire in this study included 4 parts. The first part included items to record the demographic data of the participants including gender, age, level of education, educational background, marital status, place of residence, income and experience for dentists.

The second part of the questionnaire included items to assess participants’ knowledge and awareness of black triangles in the everyday life, items to record whether the participants had previous experiences with black triangles, and items with VAS scales to measure their ratings for the impacts of black triangles on the esthetics and appearance of individuals.

The VAS scale was used to assess participants’ ratings for the impacts of black triangles on esthetics and the appearance of individuals, 0 meant no impact and 10 meant very severe negative impacts. The visual analogue scale (VAS) was used in this study because it is considered a simple, valid and reliable method for assessment48,49,50,51. Also, adequate level of reliability was shown for the VAS when was used in previous literature regarding the black triangles48,51.

The third part of the questionnaire included items to assess participants’ knowledge of the possible causes of black triangles. This part of the questionnaire assessed the participants’ knowledge of 11 investigated causes of black triangle. The participants were asked whether each one of the investigated causes could be a possible cause for black triangles or not. A total score of knowledge about causes of black triangles was calculated by denoting one for each correct answer selected by the participant (possible minimum score is 0 and possible maximum score is 11). The participants were also asked to report any other possible cause for black triangles that was not mentioned in the questionnaire.

The fourth part of the questionnaire included items to assess participants’ knowledge of the available management of black triangles. The study investigated the participants’ knowledge of 8 investigated treatments of black triangle. The participants were asked whether each one of the investigated managements could be a possible management for black triangles or not. A total score of knowledge about treatment of black triangles was calculated by denoting one for each correct answer selected by the participant (possible minimum score is 0 and possible maximum score is 8). The participants were also asked to report any other possible management for black triangles that was not mentioned in the questionnaire.

Study outcome measures

The main outcome measures for this study were participants’ knowledge regarding impacts, causes, and management of black triangles, and the level of participants’ education. The secondary outcome measures were the relationship between participants’ demographics (age, gender, and educational background) and their knowledge regarding black triangles.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis for this investigation was carried out utilizing the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics v23.0; IBM Corp., USA). The data was examined for normal distribution and the proper statistical analyses tests were then utilized. The continuous data was expressed as means, standard errors, standard deviations and confidence intervals, meanwhile the categorical data was described as frequencies, percentages, medians, minimum, maximum and interquartile ranges.

Correlations between different variables parametric variables were tested utilizing the Pearson’s r test and the Point biserial correlation (r). The independent student t-test was used for two-group comparisons, and the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test and Post hoc analyses were used for comparison between more than two groups. Comparisons for non-parametric dependent variables (each tested causes and treatments of black triangles) between dental and non-dental participants were done using the Chi Square test. In addition, two-step hierarchical multiple linear regression analyses were carried out to examine the predictive power of the group and being from dental or non-dental backgrounds on the level of knowledge regarding black triangles, while controlling for the age and gender of participants. The significance level was set as two-tailed with P < 0.05 and 95% confidence intervals for all the analyses executed.

The G*power program (version 3.1.9.7) was used to perform a priori power analysis to determine the appropriate sample size for this investigation. The ANOVA test for multiple independent variables was utilized with a total of 4 groups, a power of 0.80, a significance level of 0.05 and an effect size of 0.25 based on Alomari et al. 202212. This estimated a sample size of 180 participants. Allowing for a potential attrition rate of 20%, a sample size of 220 subjects was approximated. The invitation to participate was extended to 450 individuals, and 435 participants responded and participated in this investigation (response rate = 96.7%) and were the same cohort of patients in a previous investigation51.

Results

Overall, 435 participants (136 males (31.3%) and 299 females (68.7%)) were recruited, and had their data collected and analyzed. The participants’ mean age was 28 years old (SD = ± 10 years, age range = 18–78 years, 95% CI = 27–29 years).

Table 1 demonstrates the distribution of participants’ demographic data in this study. The study sample comprised 4 groups: dentists (n = 110), pre-clinical (3rd year) dental students (n = 104), clinical (4th and 5th year) dental students (n = 110) and laypeople (n = 111) (Table 1).

General awareness of BT and knowledge of BT impacts on smile attractiveness

Table 2 shows the participants’ general awareness of black triangles and their knowledge of the significance and impacts of black triangles on smile attractiveness among the study sample. The dentists reported the highest general awareness of black triangles whilst the laypeople reported the least general awareness of the problem. The VAS scores for rating the impacts of black triangles on the esthetics and appearance of individuals was significantly different between groups (F = 3.769, P = 0.011). Further comparisons using Tukey post hoc test revealed that dentists (mean difference = −0.8119, P = 0.014) and clinical dental students (mean difference = −0.7337, P = 0.030) reported more negative impacts of black triangles on esthetics and appearance than laypeople.

Dentists, clinical and preclinical dental students heard more about black triangles than laypeople (P < 0.05, Table 3). Dentists saw more BT between teeth and prosthesis than clinical dental students, preclinical students and laymen (P < 0.05, Table 3). Clinical dental students saw more BT between dental prosthesis than preclinical dental students and laymen (P < 0.001, Table 3).

Knowledge of the causes and treatment of BT amongst the participants

Table 4 demonstrates the distribution of the knowledge regarding the causes and treatment of black triangles amongst the study participants. The most reported cause of black triangles among the study sample was “periodontal disease” (n = 370) followed by “bone loss” (n = 232). However, the least reported cause of black triangles was the “increased overjet/overbite” (n = 76) followed by “parafunction” and “deep implants” (n = 144 each) (Table 4). Meanwhile, the most reported treatment for black triangles among the study sample was “cannot be treated” (n = 432) followed by “non-surgical periodontal treatment” (n = 292). However, the least reported treatment for black triangles was “surgery without bone graft” (n = 106) followed by “removing implants” (n = 112) (Table 4).

Table 5 shows the presence of significant differences in participants’ knowledge about the causes (F = 62.056, P < 0.001) and treatment (F = 46.120, P < 0.001) of black triangles between the study groups. Further comparisons using the Scheffe Post hoc test revealed that dentists have better knowledge about the causes of black triangles than clinical dental students, pre-clinical dental students and laypeople (P < 0.05, Table 5). Similarly, clinical dental students had better knowledge about the causes of black triangles than pre-clinical dental students and laypeople (P < 0.001, Table 5). As well, pre-clinical dental students had better knowledge about the causes of black triangles than laypeople (P = 0.037, Table 5). Furthermore, dentists had better knowledge regarding the treatment for black triangles than pre-clinical dental students and laypeople (P < 0.001, Table 5). Similarly, clinical dental students had better knowledge about the treatment for black triangles than pre-clinical dental students and laypeople (P < 0.001, Table 5).

Furthermore, the participants with dental backgrounds (Mean = 5.31 ± 2.55) had better knowledge about the causes of black triangles (t = 8.189, P < 0.001) than the non-dental participants (Mean = 2.85 ± 2.25). Also, the participants with dental backgrounds (Mean = 4.53 ± 1.74) had better knowledge about the treatment for black triangles (t = 8.289, P < 0.001) than the non-dental participants (Mean = 3.05 ± 1.41).

Additionally, the dental participants demonstrated significantly better knowledge (P < 0.05, Table 6) regarding each tested cause of black triangles than the non-dental participants, except for “parafunction” (χ2 = 0.000, P = 0.989) and “increased overjet/overbite” (χ2 = 0.900, P = 0.343). Furthermore, the dental participants demonstrated significantly better knowledge (P < 0.05, Table 6) regarding each tested type of treatment for black triangles than the non-dental participants, except for “removing implants” (χ2 = 3.314, P = 0.069) and “cannot be treated” (χ2 = 1.124, P = 0.289).

However, no significant relationship was identified between participants’ age and the total knowledge about the causes (r = −0.034, P = 0.475) or the treatment (r = −0.034, P = 0.482) for black triangles. Besides, no significant differences were found between males and females regarding the knowledge of the causes (t = 0.616, P = 0.538) and treatment (t = 1.113, P = 0.266) for black triangles.

The two-step multiple hierarchical regression analyses showed that the group significantly contributed to the total knowledge regarding the causes of black triangles (R2 = 0.296, R2 change = 0.290, B = −1.361, β = −0.566, t = −8.432, P < 0.001, 95% CI of B = −1.678 to −1.061). Being a dentist was associated with 1.361 higher odds of having better knowledge regarding the treatment of black triangles than clinical dental students, 2.72 higher odds than preclinical dental students, and 4.08 higher odds than laypeople.

Also, the group significantly contributed to the total knowledge regarding the treatment of black triangles (R2 = 0.238, R2 change = 0.234, B = −0.770, β = −0.486, t = −6.961, P < 0.001, 95% CI of B = −0.987 to −0.552). Being a dentist was associated with 0.77 higher odds of having better knowledge regarding the treatment of black triangles than clinical dental students, 1.54 higher odds than preclinical dental students, and 2.31 higher odds than laypeople.

Discussion

The results of this study revealed the existence of associations between the knowledge regarding black triangles and the study group as well as being from dental or non-dental background. Consequently, the null hypothesis was rejected.

The findings showed that the dentists had experienced more cases of black triangles in comparison to dental students and laypeople, possibly due to having higher experience and more practice experience. Also, participants with dental educational backgrounds heard more about black triangles than laypeople. This could be explained by the lack of exposure of laypeople to dental education compared to the other groups. Also, dentists and clinical dental students reported more negative impacts of black triangles on esthetics than laypeople.

This concurs with other findings showing that individuals with a dental background were more strict in their evaluation of different esthetic parameters than the laypeople12,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,52,53,54,55. However, this opposes other studies that could not find any difference28,56,57,58,59,60,61.

In contrast to this study, Kay et al. (2014) reported no difference in disutility perception between dental professionals and patients in relation to tooth loss61. They found that both dental professionals and patients value tooth loss similarly and reported more disutility as the missing teeth were nearer to the front of the mouth, except for the loss of the upper canine that was rated to cause more disutility by the dental professionals. This relates to the black triangles problem as both the loss of anterior teeth and black triangles cause spaces that lead to negative impacts on esthetics.

In addition, missing teeth would cause larger spaces than the ones that result from black triangles, and this might account for negatively perceiving the esthetics regardless being a dental professional or a patient. The differences in psychological, cultural, and social factors could also account for this contrast, as well as differences in the tested parameters and methodologies adopted during these studies.

Dental participants demonstrated better knowledge than the non-dental ones in most of the knowledge items related to the causes of and treatments for black triangles, which might be reflected by the dental education that they were exposed to.

The findings also demonstrated that the odds of having better knowledge regarding causes and treatment of black triangles were the best for dentists, followed by clinical dental students, then the preclinical dental students, and finally the laypeople. This may be explained as dentists had already completed their dental degree, and that clinical students were further ahead in their degree than the pre-clinical dental students, and so they were more likely to have gained greater knowledge related to the black triangles and be more educated than the other groups. In addition, the laypeople had no dental education in this regard which resulted in them having the least knowledge regarding the causes and treatment of black triangles. No studies could be found that compared those specific aspects, but in a similar manner, the study by Costa and colleagues found that dentists had greater knowledge about sedation, followed by dental students and laypeople62. Moreover, the work by Al-Omiri and his group found that students in the higher years had better knowledge about oral health30,63.

No differences were found between the male and female participants in this study, and no studies looking particularly at the knowledge about black triangles could be found, so studies about knowledge of other aspects of black triangles and esthetics would be referred to. For instance, studies have found opposing results, where females had better knowledge than males about the relation of sugar intake and dental caries64,65,66. Furthermore, females also had better knowledge about oral hygiene practices and oral health than males30,66,67,68. Those differences may be explained by that, in this study, different aspects were tested and, in addition, female participants were more represented in the sample, and this calls for cautious interpretation. Utilizing various methods to measure the knowledge and perception might also underline this contrast.

Also, some researchers investigated the perception of black triangles as well as other esthetic parameters and concluded that women were more judgmental in their evaluation of black triangles and perceived them as less attractive than men46,69. However, this does not agree with the results of other studies investigating different esthetic factors12,50,70,71. This might owe to variations in the methods used to evaluate perception, differences in tested esthetic parameters as well as the sample demographics and the number of female participants.

Furthermore, no significant relationships were identified between participants’ age and the total knowledge about the causes or the treatment for black triangles. This might be related to the exposure of individuals to social media and having information regardless of the age.

No studies were available to compare with in this regard, so comparison to studies that tested other aspects would be refereed to. For example, this does not agree with previous findings that younger dentists were more familiar with preventive measures than the older counterparts, which is because they were exposed to the more recent dental education curriculum that puts more emphasis on the preventive approaches72. Also, multiple studies have shown that older subjects are less critical when it comes to esthetics30,46,73,74. Nonetheless, this was not shown in other studies12,71. This contrast might be attributed to variations in evaluated age groups and sample demographics, differences in the evaluated aspects of esthetics, and differences in education.

The study limitations included that in the present study, racial, social and cultural factors were not considered during this study. Besides, the age and gender distribution were beyond control among some groups such as the dental students who had a small age range. However, careful interpretation of those factors was undertaken. In addition, the confounding effects of age and gender were considered in the hierarchical regression analysis. Furthermore, the responses to the study instrument were subjective and self-reported by the participants; however, the utilized questionnaire was simple, clear, easy to score, and the participants were well informed and had any query answered by the investigators. Also, the reliability of the items was tested and ensured. Furthermore, the participants were recruited from available locations, which may potentially limit the generalizability of the findings of the study.

More investigations are required to highlight the possible effects of cultural, social, personality and racial factors on the knowledge and perception of black triangles and the role of different educational backgrounds in this regard. Comparisons between participants from different social, cultural, and racial backgrounds would highlight the impacts of how black triangles are perceived by different populations, and provide an insight into a more holistic understanding of the black triangles problem. Evaluation of personality might also identify how various personality factors potentially impact the perception of black triangles. Also, further investigations using larger samples are advisable on different populations.

Conclusions

Within the limitations of this research, it was concluded that dental professionals have more negative perception of the impacts of black triangles on esthetics than laypeople. In addition, having a dental educational background was associated with better knowledge about the impacts, causes and treatment of black triangles.

Data availability

Data generated and analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon request to the following email: alomirim@yahoo.co.uk.

References

Gonzalez, M. K. et al. Interdental papillary house: A new concept and guide for clinicians. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 31(6), e87-93 (2011).

Sharma, A. A. & Park, J. H. Esthetic considerations in interdental papilla: Remediation and regeneration. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 22(1), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1708-8240.2009.00307.x (2010).

Sharma, P. & Sharma, P. Dental smile esthetics: The assessment and creation of the ideal smile. Semin. Orthod. 18, 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sodo.2012.04.004 (2012).

Pugliese, F., Hess, R. & Palomo, L. Black triangles: Preventing their occurrence, managing them when prevention is not practical. Semin. Orthod. 25(2), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sodo.2019.05.006 (2019).

Tarnow, D. P., Magner, A. W. & Fletcher, P. The effect of the distance from the contact point to the crest of bone on the presence or absence of the interproximal dental papilla. J. Periodontol. 63(12), 995–996. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.1992.63.12.995 (1992).

Sarver, D. M. Principles of cosmetic dentistry in orthodontics: Part 1. Shape and proportionality of anterior teeth. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 126(6), 749–753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.07.034 (2004).

An, S. S., Choi, Y. J., Kim, J. Y., Chung, C. J. & Kim, K. H. Risk factors associated with open gingival embrasures after orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod. 88(3), 267–274. https://doi.org/10.2319/061917-399.12 (2018).

Hochman, M. N., Chu, S. J., da Silva, B. P. & Tarnow, D. P. Layperson’s esthetic preference to the presence or absence of the interdental papillae in the low smile line: A web-based study. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 31(2), 113–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/jerd.12478 (2019).

Cunliffe, J. & Pretty, I. Patients’ ranking of interdental “black triangles” against other common aesthetic problems. Eur. J. Prosthodont. Restor. Dent. 17(4), 177–181 (2009).

Foulger, T. E., Tredwin, C. J., Gill, D. S. & Moles, D. R. The influence of varying maxillary incisal edge embrasure space and interproximal contact area dimensions on perceived smile aesthetics. Br. Dent. J. 209(3), E4. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.719 (2010).

Batra, P., Daing, A., Azam, I., Miglani, R. & Bhardwaj, A. Impact of altered gingival characteristics on smile esthetics: Laypersons’ perspectives by Q sort methodology. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 154(1), 82-90.e82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2017.12.010 (2018).

Alomari, S. A., Alhaija, E. S. A., AlWahadni, A. M. & Al-Tawachi, A. K. Smile microesthetics as perceived by dental professionals and laypersons. Angle Orthod. 92(1), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.2319/020521-108.1 (2022).

Singh, V. P., Uppoor, A. S., Nayak, D. G. & Shah, D. Black triangle dilemma and its management in esthetic dentistry. Dent. Res. J. (Isfahan) 10(3), 296–301 (2013).

Ziahosseini, P., Hussain, F. & Millar, B. J. Management of gingival black triangles. Br. Dent. J. 217(10), 559–563. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.1004 (2014).

Rashid, Z. J., Gul, S. S., Shaikh, M. S., Abdulkareem, A. A. & Zafar, M. S. Incidence of gingival black triangles following treatment with fixed orthodontic appliance: A systematic review. Healthcare (Basel). 10(8), 1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10081373 (2022).

Choquet, V. et al. Clinical and radiographic evaluation of the papilla level adjacent to single-tooth dental implants. A retrospective study in the maxillary anterior region. J. Periodontol. 72(10), 1364–1371. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2001.72.10.1364 (2001).

Tarnow, D. et al. Vertical distance from the crest of bone to the height of the interproximal papilla between adjacent implants. J. Periodontol. 74(12), 1785–1788. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2003.74.12.1785 (2003).

Ryser, M. R., Block, M. S. & Mercante, D. E. Correlation of papilla to crestal bone levels around single tooth implants in immediate or delayed crown protocols. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 63(8), 1184–1195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2005.04.025 (2005).

Alani, A., Maglad, A. & Nohl, F. The prosthetic management of gingival aesthetics. Br. Dent. J. 210(2), 63–69. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.2 (2011).

An, H. S., Park, J. M. & Park, E. J. Evaluation of shear bond strengths of gingiva-colored composite resin to porcelain, metal and zirconia substrates. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 3(3), 166–171. https://doi.org/10.4047/jap.2011.3.3.166 (2011).

Cardaropoli, D. & Re, S. Interdental papilla augmentation procedure following orthodontic treatment in a periodontal patient. J. Periodontol. 76(4), 655–661. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2005.76.4.655 (2005).

Cortellini, P. & Tonetti, M. S. Microsurgical approach to periodontal regeneration. Initial evaluation in a case cohort. J. Periodontol. 72(4), 559–569. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2001.72.4.559 (2001).

Kotschy, P. & Laky, M. Reconstruction of supracrestal alveolar bone lost as a result of severe chronic periodontitis. Five-year outcome: Case report. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 26(5), 425–431 (2006).

McGuire, M. K. & Scheyer, E. T. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to determine the safety and efficacy of cultured and expanded autologous fibroblast injections for the treatment of interdental papillary insufficiency associated with the papilla priming procedure. J. Periodontol. 78(1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2007.060105 (2007).

Ficho, A. C. et al. Is interdental papilla filling using hyaluronic acid a stable approach to treat black triangles? A systematic review. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 33(3), 458–465. https://doi.org/10.1111/jerd.12694 (2021).

Carnio, J. Surgical reconstruction of interdental papilla using an interposed subepithelial connective tissue graft: A case report. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 24(1), 31–37 (2004).

Patnaik, G., Singla, R. K. & Bala, S. Anatomy of a beautiful face and smile. J. Anat. Soc. India. 52, 74–80 (2003).

Kokich, V. O., Kokich, V. G. & Kiyak, H. A. Perceptions of dental professionals and laypersons to altered dental esthetics: Asymmetric and symmetric situations. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 130(2), 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.04.017 (2006).

Al-Omiri, M. K. & Karasneh, J. Relationship between oral health-related quality of life, satisfaction, and personality in patients with prosthetic rehabilitations. J. Prosthodont. 19(1), 2–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-849X.2009.00518.x (2010).

Al-Omiri, M. K., Barghout, N. H., Shaweesh, A. I. & Malkawi, Z. Level of education and gender-specific self-reported oral health behavior among dental students. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 10(1), 29–35 (2012).

Mehl, C., Wolfart, S., Vollrath, O., Wenz, H. J. & Kern, M. Perception of dental esthetics in different cultures. Int. J. Prosthodont. 27(6), 523–529. https://doi.org/10.11607/ijp.3908 (2014).

Sütterlin, C. & Yu, X. Aristotle’s dream: Evolutionary and neural aspects of aesthetic communication in the arts. Psych. J. 10(2), 224–243. https://doi.org/10.1002/pchj.416 (2021).

Al Nazeh, A. A. et al. Relationship between oral health impacts and personality profiles among orthodontic patients treated with Invisalign clear aligners. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 20459. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77470-8 (2020).

Al-Omiri, M. K. et al. Oral health status, oral health–related quality of life and personality factors among users of three-sided sonic-powered toothbrush versus conventional manual toothbrush. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 21(2), 371–381. https://doi.org/10.1111/idh.12642 (2023).

Jørnung, J. & Fardal, Ø. Perceptions of patients’ smiles: A comparison of patients’ and dentists’ opinions. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 138(12), 1544–1553. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0103 (2007) (quiz 1613–1544).

Sriphadungporn, C. & Chamnannidiadha, N. Perception of smile esthetics by laypeople of different ages. Prog. Orthod. 18(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40510-017-0162-4 (2017).

Kokich, V. O. Jr., Kiyak, H. A. & Shapiro, P. A. Comparing the perception of dentists and lay people to altered dental esthetics. J. Esthet. Dent. 11(6), 311–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1708-8240.1999.tb00414.x (1999).

Moore, T., Southard, K. A., Casko, J. S., Qian, F. & Southard, T. E. Buccal corridors and smile esthetics. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 127(2), 208–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.11.027 (2005) (quiz 261).

LaVacca, M. I., Tarnow, D. P. & Cisneros, G. J. Interdental papilla length and the perception of aesthetics. Pract. Proced. Aesthet. Dent. 17(6), 405–412 (2005) (quiz 414).

Machado, A. W., McComb, R. W., Moon, W. & Gandini, L. G. Jr. Influence of the vertical position of maxillary central incisors on the perception of smile esthetics among orthodontists and laypersons. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 25(6), 392–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/jerd.12054 (2013).

Betrine Ribeiro, J., Alecrim Figueiredo, B. & Wilson Machado, A. Does the presence of unilateral maxillary incisor edge asymmetries influence the perception of smile esthetics?. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 29(4), 291–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/jerd.12305 (2017).

Magne, P., Salem, P. & Magne, M. Influence of symmetry and balance on visual perception of a white female smile. J. Prosthet. Dent. 120(4), 573–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2018.05.008 (2018).

Revilla-León, M. et al. Perception of occlusal plane that is nonparallel to interpupillary and commissural lines but with the maxillary dental midline ideally positioned. J. Prosthet. Dent. 122(5), 482–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2019.01.023 (2019).

Babiuc, I. et al. A comparative study on the perception of dental esthetics of laypersons and dental students. Acta Medica Transilvanica. 25(2), 61–63. https://doi.org/10.2478/amtsb-2020-0034 (2020).

Pithon, M. M. et al. Esthetic perception of black spaces between maxillary central incisors by different age groups. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 143(3), 371–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2012.10.020 (2013).

Bolas-Colvee, B., Tarazona, B., Paredes-Gallardo, V. & Arias-De Luxan, S. Relationship between perception of smile esthetics and orthodontic treatment in Spanish patients. PLoS ONE 13(8), e0201102. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201102 (2018).

Tortopidis, D., Hatzikyriakos, A., Kokoti, M., Menexes, G. & Tsiggos, N. Evaluation of the relationship between subjects’ perception and professional assessment of esthetic treatment needs. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 19(3), 154–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1708-8240.2007.00089.x (2007) (discussion 163).

Atieh, D. W. A. The relationship between the perception of black triangles appearance, personality factors, and the level of education. MDSc Thesis. Jordan, Amman: The University of Jordan, 159–165 (2023).

Talic, N. & Al-Shakhs, M. Perception of facial profile attractiveness by a Saudi sample. Saudi Dent. J. 20, 17–23 (2008).

Talic, N., Alomar, S. & Almaidhan, A. Perception of Saudi dentists and lay people to altered smile esthetics. Saudi Dent. J. 25(1), 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sdentj.2012.09.001 (2013).

Al-Omiri, M. K. et al. Relationships between perception of black triangles appearance, personality factors and level of education. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 5675. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55855-3 (2024).

Pinho, S., Ciriaco, C., Faber, J. & Lenza, M. A. Impact of dental asymmetries on the perception of smile esthetics. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 132(6), 748–753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.01.039 (2007).

Nascimento, D., Santos, Ê., Machado, A. & Bittencourt, M. Influence of buccal corridor dimension on smile esthetics. Dental Press J. Orthod. 17, 145–150. https://doi.org/10.1590/S2176-94512012000500020 (2012).

Sadrhaghighi, H., Zarghami, A., Sadrhaghighi, S. & Eskandarinezhad, M. Esthetic perception of smile components by orthodontists, general dentists, dental students, artists, and laypersons. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 8(4), 12235. https://doi.org/10.1111/jicd.12235 (2017).

Ngoc, V. T. N. et al. Perceptions of dentists and non-professionals on some dental factors affecting smile aesthetics: A study from Vietnam. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17(5), 1638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051638 (2020).

Parekh, S. M., Fields, H. W., Beck, M. & Rosenstiel, S. Attractiveness of variations in the smile arc and buccal corridor space as judged by orthodontists and laymen. Angle Orthod. 76(4), 557–563. https://doi.org/10.1043/0003-3219(2006)076[0557:Aovits]2.0.Co;2 (2006).

Ritter, D. E., Gandini, L. G., Pinto Ados, S. & Locks, A. Esthetic influence of negative space in the buccal corridor during smiling. Angle Orthod. 76(2), 198–203. https://doi.org/10.1043/0003-3219(2006)076[0198:Eionsi]2.0.Co;2 (2006).

Krishnan, V., Daniel, S. T., Lazar, D. & Asok, A. Characterization of posed smile by using visual analog scale, smile arc, buccal corridor measures, and modified smile index. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 133(4), 515–523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.04.046 (2008).

Barros, E., Carvalho, M., Mello, K., Botelho, P. & Normando, D. The ability of orthodontists and laypeople in the perception of gradual reduction of dentogingival exposure while smiling. Dental Press J. Orthod. 17, 81–86. https://doi.org/10.1590/S2176-94512012000500012 (2012).

Saffarpour, A., Ghavam, M., Saffarpour, A., Dayani, R. & Fard, M. J. Perception of laypeople and dental professionals of smile esthetics. J. Dent. 13(2), 85–91 (2016).

Kay, E. J., Nassani, M. Z., Aswad, M., Abdelkader, R. S. & Tarakji, B. The disutility of tooth loss: A comparison of patient and professional values. J Public Health Dent. 74(2), 89–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/jphd.12042 (2014).

Costa, L. R. et al. Perceptions of dentists, dentistry undergraduate students, and the lay public about dental sedation. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 12(3), 182–188. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-77572004000300004 (2004).

Al-Omiri, M. K., Alhijawi, M. M., Al-Shayyab, M. H., Kielbassa, A. M. & Lynch, E. Relationship between dental students’ personality profiles and self-reported oral health behaviour. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 17(2), 125–129. https://doi.org/10.3290/j.ohpd.a42371 (2019).

Bhayat, A. Oral health knowledge and practice among administrative staff at Taibah university, Madina, KSA. Eur. J. Gen. Dent. 2, 308–311. https://doi.org/10.4103/2278-9626.116025 (2013).

Elrashid, A. et al. Correlation of sociodemographic factors and oral health knowledge among residents in Riyadh City, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Oral Health Community Dent. 12, 8–13. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10062-0018 (2018).

Rajeh, M. T. Gender differences in oral health knowledge and practices among adults in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 14, 235–244. https://doi.org/10.2147/ccide.S379171 (2022).

Halboub, E., Dhaifullah, E. & Yasin, R. Determinants of dental health status and dental health behavior among Sana’a University students, Yemen. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 4(4), 257–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-1626.2012.00156.x (2013).

Abu-Gharbieh, E. et al. Oral health knowledge and behavior among adults in the United Arab Emirates. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 7568679. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7568679 (2019).

Abu Alhaija, E. S., Al-Shamsi, N. O. & Al-Khateeb, S. Perceptions of Jordanian laypersons and dental professionals to altered smile aesthetics. Eur. J. Orthod. 33(4), 450–456. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjq100 (2011).

Omar, H. & Tai, Y. Perception of smile esthetics among dental and nondental students. J. Educ. Ethics Dent. 4(2), 54–60. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-7761.148986 (2014).

Silva, B. P., Jiménez-Castellanos, E., Martinez-de-Fuentes, R., Fernandez, A. A. & Chu, S. Perception of maxillary dental midline shift in asymmetric faces. Int. J. Esthet. Dent. 10(4), 588–596 (2015).

Yusuf, H. et al. Differences by age and sex in general dental practitioners’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviours in delivering prevention. Br. Dent. J. 219(6), E7. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.711 (2015).

Hantash, R. O., Al-Omiri, M. K., Yunis, M. A., Dar-Odeh, N. & Lynch, E. Relationship between impacts of complete denture treatment on daily living, satisfaction and personality profiles. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 12(3), 200–207. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1035 (2011).

Younis, A. et al. Relationship between dental impacts on daily living, satisfaction with the dentition and personality profiles among a Palestinian population. Odontostomatol. Trop. 35(138), 21–30 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mrs. AbdelAziz M. for her help during the preparation of this manuscript. Thanks also to the University of Jordan, King Khalid University and De Montford University for making this study possible and for providing administrative support.

Funding

This research received no external funding. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K.AL-O. conceived the study. M.K.AL-O. and D.W.A.A. designed the study. M.K.AL-O. and D.W.A.A. collected the data. M.K.AL-O., D.W.A.A., M.A.A., A.A.AlN., S.A., S.A.B.H., A.A.A., M.A.A., N.M.S. and E.L. interpreted the data, conceived the results, drafted sections of the manuscript, and revised the manuscript. M.K.AL-O. prepared the tests for the study. M.K.AL-O., D.W.A.A., M.A.A., A.A.AlN., S.A., S.A.B.H., A.A.A., M.A.A., N.M.S. and E.L. carried out the data analysis and critically revised the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the submitted final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

AL-Omiri, M.K., Atieh, D.W.A., Abu-Awwad, M. et al. The knowledge regarding the impacts and management of black triangles among dental professionals and laypeople. Sci Rep 14, 10840 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-61356-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-61356-0

Keywords

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.