Abstract

Real-world data (RWD) can provide intel (real-world evidence, RWE) for research and development, as well as policy and regulatory decision-making along the full spectrum of health care. Despite calls from global regulators for international collaborations to integrate RWE into regulatory decision-making and to bridge knowledge gaps, some challenges remain. In this work, we performed an evaluation of Austrian RWD sources using a multilateral query approach, crosschecked against previously published RWD criteria and conducted direct interviews with representative RWD source samples. This article provides an overview of 73 out of 104 RWD sources in a national legislative setting where major attempts are made to enable secondary use of RWD (e.g. law on the organisation of research, "Forschungsorganisationsgesetz"). We were able to detect omnipresent challenges associated with data silos, variable standardisation efforts and governance issues. Our findings suggest a strong need for a national health data strategy and data governance framework, which should inform researchers, as well as policy- and decision-makers, to improve RWD-based research in the healthcare sector to ultimately support actual regulatory decision-making and provide strategic information for governmental health data policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Real-world data (RWD) generate evidence for various research, development, policy and regulatory decision-making purposes along the product lifecycles of pharmaceuticals and medical devices. The increasing use1,2,3,4 of RWD also provides significant possibilities beyond the aforementioned opportunities across the full spectrum of health care, ranging from clinical trial design to the study of medical (mal-)practice5 to public health and health policy6. To account for the transformative potential of RWD, the European Union has recently passed in addition to existing legislation such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the European Data Governance Act (DGA7). Furthermore, the European Commission (EC) proposed a regulation for the European Health Data Space (EHDS8) to facilitate, among other aims, the safe and secure use and reuse of health data for better healthcare delivery, research and policy-making. The recent proposal of the EC to revise pharmaceutical legislation also emphasizes the importance of leveraging RWD in healthcare.9 However, progress in the digitalisation of health care systems is unevenly distributed across Europe10, casting doubts on achieving the ambitious aims of the EHDS. Despite ongoing initiatives like DARWIN EU11, calls from global regulators for international collaboration to integrate real-world evidence (RWE) into regulatory decision-making12 and to bridge knowledge gaps, some challenges, such as heterogeneity of data sources, linkability/sharing of data, variable quality of data and differing approaches for data access, require more and appropriate attention. In addition to the outlined ongoing changes, the results of previous work13 also indicate the necessity for increased transparency regarding the availability of national RWD sources. The checklist in this work13 covers important areas such as data management, governance, quality requirements, data privacy, research objectives, data providers, patient population, data elements, and infrastructure. The checklist incorporates the "FAIR Data Principles," which emphasize the importance of making RWD easy to find, access, use, and reuse for secondary purposes and added value. However, the applicability, value, and practicality of the previously published checklist13 on quality criteria for RWD sources have not been evaluated yet.

Research objectives

In this work, a multi-stakeholder group coordinated by the Gesellschaft für Pharmazeutische Medizin (GPMed, Austrian Society for Pharmaceutical Medicine) compiled and classified already used national RWD sources in Austria and made an in-depth assessment of the research readiness of selected datasets. The group reviewed the previously published quality checklist for RWD in pharmaceutical research and regulatory decision-making13 in terms of added value and usability in practice. The results and findings intend to emphasise the relevance of RWD and to inform researchers, health care regulators, decision-makers and strategic governmental health data policy working groups on national and international levels about their availability and currently identified limitations. The objectives are as follows:

-

to provide an initial overview of available Austrian healthcare RWD sources for research and decision-making purposes, data locations and data custodians,

-

to test and improve the previously published checklist13,

-

to discuss and conclude which data quality aspects should be applied to improve the use of RWD for scientific and regulatory purposes.

Methods

To meet the objectives, we tapped into expert knowledge within and outside the group of authors, conducted interviews, and common desktop research using search engines and employing snowballing techniques, i.e., searching research articles on Austrian healthcare and extracting the RWD source used. We applied the following research strategies:

-

Initially, based on a past survey14, we identified health data registers established by Austrian law.

-

In addition, we searched the PubMed database for publications based on Austrian RWD sources (articles in the period from February 2017 to February 2022 including the criteria ((Austria[Affiliation]) AND (Austrian[Title/Abstract])) AND (data[Title/Abstract]).

-

We then performed a targeted search for RWD on professional societies’ and universities’ websites.

-

Finally, we searched international RWD directories (e.g., OrphaNet) for Austrian RWD.

-

Fifth and finally, the authors of this paper used their practitioners’ knowledge to identify additional RWD sources in Austria.

Based on this search strategy, we extracted only healthcare-related RWD sources as described in the articles and listed those who fit the RWD definition as published previously13. We categorized results according to institutional data holder and category of the RWD source:

-

For data holders, we differentiated between types of institutions that hold the data, including (1) expert communities (loose networks of experts without any formal organization), (2) professional societies (formally organized associations), (3) universities (organization under public law), (4) government institutions (ministries and public authorities including organization under direct state control based on private law), (5) hospitals, and (6) social insurance organizations.

-

We categorized the RWD sources based on the collection’s main purpose derived from information available on the web and verified in interviews. “Main purpose” does not mean that the data cannot be used for other purposes; however, it was defined based on the intended use during RWD establishment (= database setup / inauguration). We identified seven main purposes: (1) clinical, (2) epidemiological, (3) quality assurance, (4) regulatory, (5) administrative, (6) research, and (7) informational.

-

Finally, we categorized the subject of the RWD: (1) administrative data are data that are generated in administrative activities, (2) administrative registries also follow administrative purposes but have a legal basis, (3) biobanks store biological samples, (4) disease registries: the main data unit is a disease, (5) patient registries: the main data units are human subjects, (6) product registries: the main data units are products, (7) intervention registries: the main unit is an intervention, (8) health care databases include various health care data, and (9) observational studies.

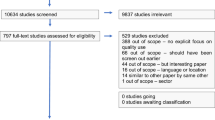

Following our objectives, we also conducted interviews with data holders on a subset of RWD sources out of the dataset “listed RWD sources” (Fig. 1). The sampling strategy was agreed upon by the author consortium and was used to create a representative RWD sample based on (1) purpose as well as (2) institutional type of data holder. During the interviews, we conducted a meticulous review of the checklist13 with the data holders, employing a systematic approach to ensure a comprehensive evaluation. To assess their own RWD sources, the interviewees utilized a rating scale for each quality criterion within the checklist, including options such as fully realized, partially realized, not realized, not realized but planned, and not applicable. Based on the participant information and consent form that we have completed with all the interview partners, we are able to utilize the aggregated and anonymized results in our work. The final scoring was determined by the authors.

Results

We identified 73 out of 104 RWD sources that met the defined criteria and objectives (Supplementary Table A). Thirty-one out of 104 RWD sources mentioned in publications were no longer findable or accessible online (Supplementary Table B). Table 1 provides an overview what data holder group holds RWD sources in what category as outlined under methods.

We identified 30 different organisations holding and managing RWD sources (Supplementary Table C), which we further grouped into seven institutional types of RWD holders (Fig. 2). Expert communities and professional academic societies owned 27 verified RWD sources in Austria. All Austrian medical universities hold at least one RWD source. For the Austrian governmental organisations, all of the main institutions appeared as data holders (e.g., Federal Ministry of Social Affairs, Health, Care and Consumer Protection (BMSGPK), Federal Office for Safety in Health Care/Austrian Medicines and Medical Devices Agency (BASG/AGES) and Austrian National Public Health Institute Gesundheit Österreich GmbH (GÖG)), and this group holds 27 RWD sources. The Austrian social insurance is also amongst the RWD holders, which already shared specific data sets for research purposes. The selected interview sample reflects the overall distribution of institutional types of RWD holders, as shown in Fig. 3.

The majority of identified and verified RWD sources are registries (89%) followed by health care databases (4%), biobanks (3%), observational collections (3%) and administrative data collections (1%). Thirty-nine RWD sources belonged to the category “disease registry” (Fig. 4). The distribution of the main purpose mainly follows a functional differentiation: governmental organisations and social insurance carriers hold RWD sources with an administrative and quality assurance purpose. Governmental organisations are also central for RWD with an epidemiological and regulatory purpose (Fig. 5). Medical universities as well as professional organisations often run clinical RWD sources. More strikingly, there are only a few RWD sources whose main purpose lies in research (beyond clinical questions). Despite the small size of the subset consisting of 11 RWD sources, which were utilized for conducting interviews with the representative data holders, we present Fig. 6 as an overview to demonstrate that the distribution of the 'main purpose' among the subset is comparable to the dataset of '73 listed RWD sources' mentioned in Supplementary Table A.

Following our approach to cluster identified RWD sources by disease area or topic wise, most RWD sources in the clinical and/or epidemiological domain can be mapped to the disease area “cancer” (26 out of the 73, Fig. 7), as RWD sources in cardiovascular diseases do in quality assurance. Due to the strict regulation of the pharmaceutical domain, a high number of RWD for regulatory, administrative and quality assurance purposes exist. Only a few remaining RWD sources focus on other specific diseases.

In line with our research objective to assess and enhance the previously published checklist13, the results of the conducted interviews, which were based on a subset of 11 RWD sources (as shown in Fig. 1), revealed that this particular subset of RWD sources already fulfilled numerous quality criteria outlined in the checklist. The parameters "Infrastructure”, "Data Elements", "Data Provider" and “Quality requirements” stood out as the most commonly fulfilled criteria (Fig. 8). Among the four FAIR Data Principles, the principle of 'Findable'—essentially referring to the ease of locating the data source through a website or online research—was found to be the least fulfilled when compared to the principles of 'Accessible', 'Interoperable', and 'Reusable'. This indicates that data owners should pay particular attention to addressing this fundamental principle. Based on our overall research approach and the experience we gained, the results of the interviews clearly demonstrate that the challenges we encountered during our own research, particularly in terms of "finding" the relevant RWD sources, were subjectively perceived as cumbersome and time-consuming. The quality criterion "data privacy and transparency" produced low ratings due to the ambiguous interpretation resulting from the type of regulations used, e.g., informed consent processes and GDPR for research vs. national regulations implemented by law. The same applied to the low rating of “Research objectives”, since RWD sources set up by law do not necessarily follow a research question or protocol such as the approach inherent to classic clinical research projects. This also concerned the parameter “Patient population covered” due to the heterogeneity and disease-specification not applying to the general population.

The interviews provided us with valuable feedback so that we were able to revise the checklist13 and interviewees had the opportunity to self-assess their own RWD sources utilizing the checklist. The overall average results of these self-assessments from the 11 interviews are presented in Fig. 8. The checklist has undergone minor revisions, including the addition of references and improvements in language. We have added headlines and an additional column with for rating options. However, the sub-element "core RWD set collected for RWD use case or purpose" in the data-elements section has been removed for usability reasons. The revised version of the checklist can be found in Table 2.

Discussion

Our research approach to identify RWD sources out of publications reveals various challenges concerning the availability and accessibility of the national RWD landscape. The considerable effort invested in this work to identify RWD resources underscored the importance of providing a central directory for RWD sources aligned with DGA7 and EHDS15 requirements (e.g., data catalogues) to facilitate research with high-quality data sets, which could serve as a valuable resource for all stakeholders. The time and resources required to search for and locate each of the identified RWD sources were a major obstacle to utilizing the available data sets in a more efficient manner.

Several RWD sources identified in the search process were not findable online (31 of 104 RWD sources, Supplementary Table B). It remains unclear if adequate metadata descriptions of these RWD sources were just unavailable or if they have been deleted since. This, however, puts the research integrity of these sources, notably data transparency and reproducibility, into question. This highlights the importance of data holders ensuring the long-term accessibility of collected RWD, enabling their reuse for (secondary) research purposes. Without such accessibility features, the potential benefits of using RWD for research, public health policy, and society in general cannot be reached.

RWD with a dedicated research purpose used in the analysed articles were rather a national exception. Predominantly, publications on RWD data sets are characterised by the secondary use of quality assurance data or epidemiological RWD, indicating a gap in the integration of academic research into public health policy-making in Austria. This suggests that aside the primary intention to establish a register, the possibility of opening the register data for further research or decision-making purposes (secondary data use) was not or only partially considered. The limited availability of RWD collected for research purposes hinders the potential to develop evidence-based policies and strategies that could positively impact public health outcomes in the country.

Expert communities and professional societies hold a substantial number of RWD sources. However, these organizations are often characterized by lacking adequate resources to maintain robust data management practices, e.g. up-to-date content and long-term availability. Due to missing directories, lacking online meta data descriptions and undefined rules for third party access, these RWD sources appear to be data silos or “club good” for “insiders” and cannot provide any benefit for healthcare research or policymaking.

The population of RWD data holders in Austria is quite diverse ranging from small professional societies to large public authorities. While this diversity could prove beneficial, this is also a source of the siloization of health data in Austria as demonstrated by the fact that barely any article in our sample used more than one data set in each publication due to legal and technical restrictions.

These findings prompt a critical discussion regarding the current state of working with or setting up RWD sources that do not adhere to FAIR data principles. It raises the question of whether such practices can still be considered state-of-the-art demonstrating a striking contrast to the initiatives on the European level as stated in the introduction. A substantial share of the RWD sources was not findable (Table 2). Accessibility was another major issue, either based on the lacking “findability”, or if findable on undefined rules for third party access. This concerns also public RWD where some institutions could use administrative datasets based on contracts, but given the transaction costs, this impedes smaller research groups and individual researchers to use these data. Therefore, the prevalence of data silos and the lack of data interoperability and standardization12 continues to pose challenges in this fragmented RWD landscape impeding the potential of RWD in general. The shortcomings of the RWD landscape in Austria have shown that the previously published RWD quality checklist13 and the feedback from the interviewees were valuable resources to inform future RWD efforts to consider multifunctional use of the data in the long term. A response was: "We would have needed this checklist before we built the registry".

Furthermore, the findings of the interviews confirmed our initial assumption that research readiness for secondary purposes and broader applicability were albeit often, forgotten during the inauguration of RWD sources. In the assessment of the checklist by the interviewees, registers/cohorts dedicated to specific purposes tended to receive high scores in terms of research readiness. However, their usefulness was limited due to the prevailing data siloization. This lack of data integration and interoperability prevents researchers from harnessing the full benefits of these "research-ready" datasets, leading to their underutilization. Interestingly, some of the most comprehensive and interesting RWD sources out of the subset score low on the checklist criteria, putting their value as RWD source into question. However, following our broad definition of RWD13 not every RWD source is inaugurated based on a research objective (e.g. health care claims data). This might highlight the prevailing marginal status of RWD utilization, as these valuable datasets remain underutilized and underappreciated in the research community. We also received valuable and constructive suggestions on how to further improve or adapt the criteria listed in the checklist so that it can be used more broadly (Table 2).

Conclusion

The health data landscape changes constantly due to new data collection points, cheaper and faster availability of omics data, digital health and digital care pathways, imaging technology and artificial intelligence. This evolution creates opportunities not only for healthcare research and development but also for public health and health policy6. This necessitates increased coordination, the creation of common (meta)data standards and interoperability to avoid siloization and to maximise the benefits of RWD through data exploration in linked data sets, which are able to represent the complexities of public and individual health issues.

However, the legislative environment is not yet ready to support RWD within the boundaries of fundamental rights. This is for several reasons, not all of them being purely of a legal nature. Strictly legally speaking, Austria already made a major attempt to increase access to secondary use of data via several reforms of the federal law on the organisation of research (“Forschungsorganisationsgesetz”) and of the law on statistics (“Bundesstatistikgesetz”) in 201816 and in 202117,18, respectively. The aim of these reforms was to increase the accessibility of existing (personal) data for research purposes. However, for several reasons, including the lack of secondary legislation on a ministerial level that would have been needed and due to legal complexity, these attempts have not yet sufficiently reached their goals. The already complex national situation faces new challenges by the planned European legislative initiatives, in particular the DGA7 and the EHDS Act15. The DGA aims to improve data sharing and data reuse within the European Union (EU) by introducing, inter alia, competent bodies (Art. 7), single information points (Art. 8), data intermediation services (Art. 10) and public registers of recognised data altruism organisations (Art. 17). The EHDS will likely introduce a whole chapter on the secondary use of electronic health data (Chapter IV), introducing health data access bodies (Art. 36), rules on data altruism in health (Art. 40), a cross-border infrastructure for secondary use of electronic health data (HealthData@EU) (Art. 52) and new governance bodies such as the EHDS Board (Art. 64). Whereas these European attempts have the potential to improve the accessibility of RWD, there exists at the same time a significant risk of even more legal complexity by legal inconsistency, national deviations and unclarity as an unwanted offspring of these initiatives.

High-quality criteria for RWD are key for improved data utilization in research and healthcare decision-making4. The herein provided improved checklist (Table 2) may also support authorities and government institutions in their attempt to ensure data quality for the whole sector, in particular with regard to the implementation of the DGA and the coming EHDS as well as national and European activities of open science. RWD sources can foster a more open culture of data sharing and reuse, which is unfortunately almost absent in the currently reviewed health data sector.

We also call for a critical, scientifically driven analysis of the regulatory environment, together with an attempt to simplify the legal landscape, and more ambitious and structured governance activities regarding health data, in particular for a more comprehensive approach to data collection, considering the potential for future research and wider utilization. Multipurpose datasets may increase efficiency and may act as a boost for research on topics that are often neglected due to the lack of data. A significant improvement in data utilization could be achieved through better linking of data from both public and private sources. Our findings emphasize the creation of a comprehensive data strategy in the healthcare domain, especially in the reviewed national framework in Austria.

On the upside, Austria employs already sector-specific personal identifiers to link data across data sets without compromising privacy and data protection (the so-called "bereichsspezifische Personenkennzeichen (bPK)"), and the recently established Austria Microdata Center (AMDC) at Statistics Austria can serve as a role model for the use of administrative and statistical data for research (legally, technically, organisational).

Future legislative developments at the EU level (e.g. EHDS15 or pharma legislation9), the efforts of the HMA/EMA Big Data Steering Group19 and in particular the European Medicines Regulatory Network (EMRN) and the RWD for Decision Making Network (RWD4DM) will provide significant impetus.

Recent national developments such as the government’s introduction of the Digital Austria Act20 in mid-2023 and the recommendations of the “Digitalization and Registries Working Group” to create an Austrian health data space21 indicate that there is more awareness of better data use in national health policy. Further encouraging signals regarding the improvement of the secondary use of health data can be found in the “eHealth Strategy”22 as well as in the national healthcare measures within the federal finance act23 presented in November 2023.

While governments have a responsibility to create clear legal frameworks, data holders have no less responsibility to ensure that RWD is made accessible and usable in accordance with new regulations. However, if the goals and plans set are not followed by action, then no added value can be generated from the use of RWD for each individual, society and the healthcare system. In conclusion, the findings underscore the need for:

-

a central directory of RWD that also helps to enact quality standards on data sets,

-

raising awareness and compliance with data standards, in particular the “Findable”–“Accessible”–“Interoperable”–“Reusable” (FAIR) data principles given that a substantial share of RWD is neither findable nor accessible,

-

a more strategic approach to think about the roles and features of existing and future data sets, in particular by including the research purpose in RWD,

-

resolving issues to warrant sustainable data management by providing adequate resources,

-

a fundamental legal work and willingness to simplify the existing national legislation as well as to adapt it in an RWD-supportive manner to the (reformed) EU-layer of relevant secondary law and to,

-

leave data silo-ization behind and start creating interoperable data sets.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the PubMed research approach described in the methods section are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All data analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Burns, L. et al. Real-world evidence for regulatory decision-making: Guidance from around the world. Clin. Ther. 44(3), 420–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2022.01.012 (2022).

Valla, V. et al. Use of real-world evidence for international regulatory decision making in medical devices. Int. J. Digital Health. 3, 1. https://doi.org/10.29337/ijdh.50 (2023).

Baumfeld, A. E. et al. Trial designs using real-world data: The changing landscape of the regulatory approval process. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 29, 1201–1212. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.4932 (2020).

European Medicines Agency. High-Quality Data to Empower Data-Driven Medicines Regulation in the European Union. News 10/10. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/high-quality-data-empower-data-driven-medicines-regulation-european-union (2022).

Rudrapatna, V. A. & Butte, A. J. Opportunities and challenges in using real-world data for health care. J. Clin. Invest. 130(2), 565–574. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI129197 (2020).

Degelsegger-Márquez, A. The future of European health (data) systems. PHIRI Spring School on Health Information. https://jasmin.goeg.at/2768/1/PHIRI%20Spring%20School%202023%20-ADM.pdf (2023).

Regulation (EU) 2022/868 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2022 on European data governance and amending Regulation (EU) 2018/1724 (Data Governance Act). EUR-Lex. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32022R0868 (2022).

European Commission. Public Health. eHealth: Digital Health and Care. European Health Data Space. https://health.ec.europa.eu/ehealth-digital-health-and-care/european-health-data-space_en.

European Commission. Public Health. Reform of the EU Pharmaceutical Legislation. https://health.ec.europa.eu/medicinal-products/pharmaceutical-strategy-europe/reform-eu-pharmaceutical-legislation_en.

Thiel, R. et al. #SmartHealthSystems. Digitalisierungsstrategien im internationalen Vergleich. Bertelsmann Stiftung (HRSG). https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/de/publikationen/publikation/did/smarthealthsystems (2018).

European Medicines Agency. Data Analysis and Real World Interrogation Network (DARWIN EU). https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/about-us/how-we-work/big-data/data-analysis-real-world-interrogation-network-darwin-eu#share.

European Medicines Agency. Global Regulators Call for International Collaboration to Integrate Real-World Evidence into Regulatory Decision-Making. News 22/07. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/global-regulators-call-international-collaboration-integrate-real-world-evidence-regulatory-decision (2022).

Klimek, P. et al. Quality criteria for real-world data in pharmaceutical research and health care decision-making: Austrian expert consensus. JMIR Med. Inform. 10(6), e34204. https://doi.org/10.2196/34204 (2022).

Degelsegger‐Márquez, A. Gesundheitsdaten in Österreich—ein Überblick. Gesundheit Österreich. https://jasmin.goeg.at/id/eprint/2023 (2021).

Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the European Health Data Space. COM/2022/197 final. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52022PC0197 (2022).

Feldman, K., Johnson, R. A. & Chawla, N. V. The state of data in healthcare: path towards standardization. J. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2, 248–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41666-018-0019-8 (2018).

Bundesgesetzblatt. Datenschutz-Anpassungsgesetz 2018—Wissenschaft und Forschung – WFDSAG 2018. BGBl. I Nr. 31/2018. https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/eli/bgbl/I/2018/31 (2018).

Bundesgesetzblatt. Änderung des Bundesstatistikgesetzes 2000 und des Forschungsorganisationsgesetzes. BGBl. I Nr. 205/2021. https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/eli/bgbl/I/2021/205 (2021).

EMA/HMA Big Data Big Data Steering Group. Workplan 2023–2025. Version 1.1—September 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/work-programme/workplan-2023-2025-hma/ema-joint-big-data-steering-group_en.pdf (2023).

Staatssekretariat für Digitalisierung, Bundesministerium für Finanzen. Digital Austria Act. Das Digitale Arbeitsprogramm der Bundesregierung. Digitales Gesundheitswesen. https://www.digitalaustria.gv.at/Strategien/Digital-Austria-Act---das-digitale-Arbeitsprogramm-der-Bundesregierung.html (2023).

Aigner, G. et al. Grundlagenpapier zur Schaffung des österreichischen Gesundheitsdatenraumes. Arbeitsgruppe Digitalisierung und Register des Obersten Sanitätsrates. IERM-Working-Paper Nr. 12. https://ierm.univie.ac.at/fileadmin/user_upload/i_ierm/Varanstaltungen/WP_12_-_Aigner_et_al._-_Grundlagenpapier_zur_Schaffung_des_oesterreichischen_Gesundheitsdatenraumes.pdf (2023).

Bundesministerium für Finanzen. Pressemeldungen November 2023. Rauch/Tursky: Digitale Gesundheitsreform bringt entscheidenden Beitrag zur Entlastung des Gesundheitssystems. https://www.bmf.gv.at/presse/pressemeldungen/2023/november/digitalisierung-gesundheitsbereich.html (2023).

Parlament Österreich. Parlamentskorrespondenz Nr. 1232 vom 22.11.2023. Rauch: Insgesamt 5 Mrd. € mehr für das Gesundheitswesen bis zum Jahr 2028. https://www.parlament.gv.at/aktuelles/pk/jahr_2023/pk1232 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.M., V.M. and M.S. conceived and conducted the research strategies and methodologies. D.B., T.C., P.K., DB.L., B.M., V.M., J.P-D. and M.S. conceived and conducted the deep dive interview(s). D.B., T.C., G.G-L., P.K., DB.L., B.M., V.M., J.P-D., M.S. and T.S. and analysed the results. All authors derived conclusions and discussion points. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors declare no financial support or funding for this project. D.B. is an employee of Amgen GmbH, Vienna, Austria. B.M. is an employee of Novartis Pharma GmbH, Vienna, Austria. V.M. and J.P-D. are employees of Roche Austria GmbH, Vienna, Austria. All other authors declare no other conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mikl, V., Baltic, D., Czypionka, T. et al. A national evaluation analysis and expert interview study of real-world data sources for research and healthcare decision-making. Sci Rep 14, 9751 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-59475-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-59475-9

Keywords

- Real-world data

- Real-world evidence

- Data quality

- Data quality criteria

- Health data use

- Secondary use of health data

- Health data strategy

- FAIR data principles

- Data quality recommendations

- Pharmaceutical research

- Healthcare decision-making

- Quality criteria for RWD in health care

- Gesellschaft für Pharmazeutische Medizin

- GPMed

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.