Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic, progressive and debilitating disease that affects quality of life (QOL), especially among patients living in poor environments. This study aimed to determine the influencing factors of good QOL among COPD patients living in Zhejiang, China. A cross-sectional study was conducted to collect data from participants in six tertiary hospitals in Zhejiang Province by a simple random sampling method. A validated questionnaire was used to collect general information, environmental factors, and COPD stage. The standardized St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) was used to assess QOL. Logistic regression was used to determine influencing factors of good QOL among COPD patients at a significance level of α = 0.05. A total of 420 participants were recruited for analysis. The overall prevalence of patients with good QOL was 25.7%. Six variables were found to be associated with good QOL in the multivariable analysis. Patients who were employed had 2.35 times (95% CI 1.03–5.34) greater odds of having good QOL than those who were unemployed. Those whose family income was higher than 100,000 CNY had 2.49 times (95% CI 1.15–5.39) greater odds of having good QOL than those whose family income was lower than 100,000 CNY. Those who had treatment expenses less than 5,000 CNY had 4.57 (95% CI 1.57–13.30) times greater odds of having good QOL than those who had treatment expenses of 5,000 CNY or higher. Those who had mild or moderate airflow limitation were 5.27 times (95% CI 1.61–17.26) more likely to have good QOL than those who were in a severe or very severe stage of COPD. Those who had a duration of illness less than 60 months had 5.57 times (95% CI 1.40–22.12) greater odds of having good QOL than those who had a duration of illness of 120 months or more. Those who were not hospitalized within the past 3 months had 9.39 times (95% CI 1.62–54.43) greater odds of having good QOL than those who were hospitalized more than twice over the past 3 months. Socioeconomic status, disease stage and accessibility were associated with good QOL among COPD patients in Zhejiang Province, China. Increasing family income and implementing measures to improve the accessibility of medical care, including developing a proper system to decrease the cost of treatment for COPD patients, can improve patients’ QOL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a substantial public health concern worldwide1 and is an irreversible progressive disease characterized by persistent airflow limitation2. COPD has been identified as the fourth leading cause of death worldwide and is projected to be the third leading cause of death in middle-income countries by 20303. COPD is also defined as a disease with one of the largest health economic burdens in many countries, including China4. The Chinese government spent more than $73 billion caring for and treating patients with several chronic diseases, including COPD5. Moreover, the prevalence of COPD among Chinese individuals aged 40 years or older increased from 7.6% in 2009 to 13.7% in 20186,7. The mortality rate was 79.4 per 100,000 population in 2013, which was higher than the global mortality rate (50.7 per 100,000 people) in the same year8. In the context of an aging society, including economic development based on industry, many people will suffer from COPD in China9.

The main problem for COPD patients is quality of life (QOL)10. Several factors contribute to the level of QOL among COPD patients, including its pathogenesis according to patients’ traits, socioeconomic status, and family support. Most COPD patients often suffer from poor QOL beyond suffering from its pathogenesis, such as symptoms and limited medical access9,11,12,13. A large proportion of COPD research conducted in China focuses on treatment and care, while a few publications emphasize the improvement in QOL in these populations by using the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ)14,15. However, the QOL of COPD patients should be one of the most important issues for public health, particularly during the pandemic of COVID-19 due to both diseases’ impact on human lungs16. The suffering of COPD patients in China increased because of the incomplete function of healthcare services in China, ultimately leading to poor QOL.

COPD prevalence varies across different areas in China. The prevalence of COPD in Zhejiang Province, which is one of the largest, high-density, and industrial areas, ranges between 12.8 and 14.5% among people aged 40 or older17,18. COPD was reported as the main public health problem in Zhejiang Province, and its healthcare services system was the most highly impacted in China6,7,18,19. Zhejiang Province is the third largest industrial province in China with high levels of industrial emissions19. A large proportion of people aged 40 years and over smoke, and the environment has very poor air quality20,21, including exposure to outdoor air pollution from industrial factories and agricultural burning by residents; COPD patients face a problem regarding QOL22,23. Nevertheless, there is no scientific information about QOL among COPD patients living in areas with poor air pollution, such as Zhejiang Province, China. Therefore, this study aimed to assess QOL and determine the factors associated with good QOL among COPD patients in Zhejiang Province, China.

Methods

Study design and setting

An analytical cross-sectional study was used to assess the level of QOL among COPD patients and determine the factors associated with good QOL among COPD patients in the respiratory departments of six tertiary hospitals in Zhejiang Province, Southeast China.

Study population and study sample

The study population was COPD patients who attended one of six hospitals in Zhejiang Province, China. The inclusion criteria were those aged 40 years and over and who were diagnosed with COPD by a physician. However, those who had been diagnosed with lung cancer, bronchiectasis, pneumoconiosis, or other restrictive lung ventilation dysfunction were excluded from this study.

The sample size was calculated by the standard formula for a cross-sectional study24, n = [Z2α/2 PQ]/e2, where \(Z\) = the value of the standard normal distribution corresponding to the desired confidence level (\(Z=\) 1.96 for 95% CI); P is the prevalence of good QOL among COPD patients in China at 14.1%, which was 0.1425; Q is the difference of one and P (1-P); and e is the desired precision (0.05 or 5%). Allowing for 15% error throughout the study process, at least 213 individuals were required for the analysis.

After the sample size was calculated, six tertiary hospitals were randomly selected from among 108 hospitals by a computer-generated randomization method, as shown in the following flowchart (Fig. 1). To ensure that each sample site had an equal probability of providing a sample, simple random sampling with a proportional allocation of 0.25% was used to select the sample at each study site. Those who were selected were screened according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria before the initiation of data collection.

Research instruments

A validated questionnaire and the standardized SGRQ26 were used for data collection. The validated questionnaire was developed according to the relevant literature and guidelines and discussed with experts in the field. The questionnaire consisted of three parts: general information about the participants, environmental factors, and the stage and treatment of COPD. In part one, twelve questions were used to collect general information about the participants, such as age, sex, marital status, educational level, occupational status, and household income. In part two, five questions were used to collect information on environmental factors such as residence, distance to the hospital, and hospital transport method. In the last part, five questions were used to collect information on the COPD stage and treatment of the participants.

The standardized SGRQ26 was used to assess QOL among the participants. The SGRQ contains 50 items for assessing QOL in 3 domains: symptoms, activity, and impact. Each questionnaire response has a unique empirically derived ‘weight’26. SGRQ scores range from “0” to “100”, and “0” represents the best QOL. Finally, the participants were divided into three levels of QOL according to their scores: poor (scores of 66.68–100.00), moderate (scores of 33.34–66.67), and good (scores of 0.00–33.33)27. The Mandarin Chinese version of the SGRQ was provided by St. George’s, University of London, and had been tested as a valid and responsive tool for assessing the QOL of Chinese COPD patients in China28.

Research instrument development

All questions were examined for validity and reliability by the item-objective congruence (IOC) method29 and verified by three external experts in the field: a medical doctor, an epidemiological expert, and a nurse. Each expert evaluated each item, and the scores ranged from − 1 to + 1 (if a question complied with the study scope and objective, it was scored + 1, suspicious = 0, and inconsistent = − 1). For the evaluation results, questions that scored an average score ≥ 0.70 were included in the questionnaire. The questions with average scores between 0.51 and 0.70 were modified before being included in the questionnaire. Questions with an average score below 0.5 were excluded from the questionnaire.

Before data collection, a pilot test was conducted at two selected tertiary hospitals in Zhejiang Province with 30 samples (15 samples from each) who had similar characteristics to the study sample. Only the questions with Cronbach’s alpha value ≥ 0.75 were included in the questionnaire. Finally, all the questions were reviewed by the research team before the data collection began.

Measures

Body mass index (BMI) was classified into three categories: less than 18.50 (underweight), 18.5–23.9 (normal weight), and ≤ 24.0 (overweight)30. The airflow limitation severity in COPD was classified into four levels: mild (forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) ≥ 80% of predicted), moderate (50% predicted ≤ FEV1 < 80% predicted), severe (30% predicted ≤ FEV1 < 50% predicted) and very severe (FEV1 < 30% predicted)2. The QOL among COPD patients was classified by the standardized SGRQ into three levels: poor, moderate, and good.

Data collection procedure

Six tertiary hospitals from among 108 hospitals with respiratory departments listed by the Ministry of Health and Population were randomly selected by a computer-generated randomization method and divided into two categories: tertiary class A hospitals and tertiary class B hospitals. Permission to assess the hospital was granted by the department director after sending official letters. The respiratory department staff were contacted to explain the purpose and questionnaire again to obtain their agreement to collect data in both outpatient and inpatient departments.

The purpose of this study and the content of the questionnaire were explained to the selected participants. Afterward, a written informed consent form was signed before starting data collection. The questionnaires were completed by the researcher. One hundred ninety-one participants were interviewed face-to-face, and 229 participants were interviewed by telephone due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Each face-to-face interview took 30 min, and each telephone interview took 40 min. Before ending the interview, completed questionnaires were checked again to ensure that there were no missing data. Data were collected between October and December 2021.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered into the spreadsheet and checked for any errors before being imported into the SPSS program (Version 24, Chicago, IL). Continuous data were analyzed and are presented as frequencies, means, maximums, minimums, and standard deviations to describe the participants’ characteristics. Categorical data are presented as percentages. QOL was divided into three levels: low, moderate, and high.

A chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used to preliminarily test the associations between factors and good QOL. Logistic regression was used to determine the associations of factors and good QOL at a significance level α = 0.05 in both univariate and multivariate analyses. In the multivariate analysis, all predicted variables were entered into the model before non-statistical variable(s) were considered to exclude from the model. In this step, one most non-statistical variable was excluded from the model first, and considered the fit of the model by using the Hosmer–Lemeshow chi-square test before excluding the remaining non-statistical variable(s) in the model. The Cox-Snell R2 and Nagelkerke R2 were used to determine the fitness of the model before interpreting the final model.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from Mae Fah Luang University (No. EC 21073-18). Participants were recruited on a voluntary basis. On the date of data collection, each participant received all the necessary information about the study protocol, the purpose of the survey and the potential risks. Participants were asked to sign consent forms before starting the interview. The study procedures were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines, regulations, and within the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5).

Results

A total of 420 COPD patients were recruited into this analysis: 56.4% were males, 48.1% were aged 70 years and over, and 67.1% were married. Approximately one-fifth (21.2%) were illiterate, 73.3% were unemployed, and 57.9% had an annual family income of less than 100,000 CNY ($14,750). Approximately twenty percent of participants (19.2%) faced problems with medical expenses, 69.8.0% self-paid for medical expenses, 73.3% had comorbidities, and 18.3% were current smokers (Table 1).

Nearly half of the participants (47.6%) lived in rural areas, and 48.3% went to a hospital by themselves. Half of the participants (43.8.0%) lived with others, and 40.5% had experienced exposure to secondhand smoke (Table 2).

Almost half (49.5%) had severe airflow limitation. A large proportion (61.9%) were reported to have been diagnosed with COPD for 60 months or more, 44.8% did not have home oxygen therapy available, and 49% had been hospitalized at least once in the past three months. A large proportion (62.9%) had visited their doctor 5 times or more in the last three months. Only one-fourth (25.7%) of the participants had good QOL (Table 3).

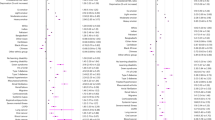

In the univariable analysis, 16 variables were found to be associated with good QOL: age, annual family income, cost of COPD treatment, BMI, medical insurance, number of comorbidities and types of comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes, and osteoporosis, current cigarette smoking, duration of smoking, distance from residence to hospital, exposure to secondhand smoke, airflow limitation severity, duration of illness, home oxygen therapy, number of hospitalizations within the past 3 months and doctor visits within the past 3 months. Other variables were not found to be associated with QOL (Table 4).

In the multivariable analysis, six variables were found to be associated with good QOL. Patients who were employed had 2.35 times (95% CI 1.03–5.34) greater odds of having good QOL than those who were unemployed. Those whose family income was higher than 1,00,000 CNY had 2.49 times (95% CI 1.15–5.39) greater odds of having good QOL than those whose family income was lower than 1,00,000 CNY. Those who had treatment expenses of less than 5000 CNY had 4.57 times (95% CI 1.57–13.30) greater odds of having good QOL than those who had treatment expenses of 5000 CNY or higher. Those who had mild or moderate airflow limitation had 5.27 times (95% CI 1.61–17.26) greater odds of having good QOL than those who had severe or very severe airflow limitation. Those who had a duration of illness less than 60 months had 5.57 times (95% CI 1.40–22.12) greater odds of having good QOL than those who had a duration of illness of 120 months or more. Those who had not been hospitalized within the past 3 months had 9.39 times (95% CI 1.62–54.43) greater odds of having good QOL than those who were hospitalized more than twice over the past 3 months (Table 4).

Discussion

Only one-third (24.8%) of the COPD patients who lived in Zhejiang Province, Chinn had poor QOL. Several factors were detected as contributors to having good QOL among COPD including employment status, high income, having been charged low treatment fees, having mild and moderated airflow limitation, having been diagnosed with COPD less than 60 months, and having never been admitted in a hospital.

The majority of people living in Zhejiang Province, China, had an annual family income of $14,750, which was higher than that of people living in other regions of China. COPD patients living in Shandong Province, where people had an annual family income lower than that in Zhejiang, had a lower proportion of good QOL25,31. Those people who lived in higher-income areas had higher levels of health insurance coverage, which supported them in accessing medical care and having better QOL than those who lived in poorer areas and had lower levels of health insurance coverage25,31. This finding confirmed that COPD patients living in high-income areas have better QOL. This means that those who have a higher income would have a better opportunity for early diagnosis, treatment, and continuous care. Once carefully and continuously cared for, patients would have better QOL and less opportunity to be hospitalized due to poor management of the disease. Moreover, we found that COPD patients who were employed had better QOL than those who were not employed. Kupcewicz et al.32 reported that COPD patients who were employed had better QOL than those who were retired. However, a large proportion of COPD patients were not actively working33,34. Due to its pathogenesis, the disease and the burden of medical expenses could be key impact factors of QOL as well33.

Even in our study, smoking was not found to be associated with QOL among COPD patients. However, many studies35,36,37 have reported that smoking is a key factor of poor QOL among COPD patients. Smoking was reported as a significant risk factor for hospitalization among COPD patients38,39, especially among COPD patients with poor economic status39. A study in Korea40,41 reported that COPD patients with a low family income had a greater chance of using cigarettes and had poorer QOL. This could reflect that COPD patients with a poor economic status have a greater chance of stress and start smoking, followed by a severe stage of COPD and low QOL.

Medical expenses or the cost of treatment was a significant factor associated with QOL among COPD patients living in Zhejiang Province, China. Medications account for the highest proportion of total medical costs for COPD patients42,43. Zhu et al.14 and Li et al.44 reported that a high medical cost was a direct factor in reducing QOL among COPD patients. Unaffordable medical costs of COPD patients were associated with a poor stage of COPD and poor QOL14. Basically, COPD patients need to attend a hospital regularly to check their health and obtain medications throughout their lives. If a patient cannot pay for medication, they enter a poor stage of the disease and have difficulty breathing, which directly impacts their QOL. Thus, affordable medical care is a significant factor in good QOL among COPD patients.

Our study clearly showed that the severity of airflow limitation among COPD patients was associated with their QOL. It is well known that impairment of lung function leads to a reduction in patients’ ability to carry out daily activities2,45. COPD patients with severe airflow limitation often experience dyspnea, cough, fatigue, and declining lung function46,47. This affects their participation in social activities, including the limitation of occupational opportunities and interactions with their family members and other social activities. This could develop the individual’s perception of being a burden to others because they need assistance to complete daily activities and finally manifest as impaired QOL48. Several studies49,50 reported that COPD patients had poor QOL due to personal perceptions of their family members’ burden, especially in the mental health domain.

We found that a longer course of disease led to a poorer level of QOL among COPD patients. On the other hand, those who had a shorter period of COPD development had better QOL than those who had a longer COPD diagnosis. Jankowska-Polańska et al.51 also reported that COPD patients who lived for a shorter duration with the disease had a better QOL than those who had lived longer with the disease. Divo et al.50 reported that COPD patients who had lived with the disease longer had a greater opportunity to have a heavy cough in daily life than those who had lived with COPD for a shorter time. The study52 also reported that coughing was a major sign associated with the QOL of COPD patients. Patients diagnosed over a longer period had a greater chance of being hospitalized than those diagnosed over a shorter period52. Several studies53,54,55,56 reported that COPD patients who had been hospitalized presented panic or mental health problems compared with those who did not, eventually resulting in poorer QOL. Patients with longer illness could face a severe decline in mental health due to the stage of pathogenesis, lack of social interaction, and poorer self-confidence, resulting in poor QOL.

A greater number of hospitalizations indicated disease severity and patients with repeated admissions had significantly reduced QOL. Many studies57,58,59 reported that COPD patients who had been hospitalized had poorer QOL. Physical, psychological, and social life impacts were detected among COPD patients who were frequently admitted to a hospital60,61,62, which directly impacted QOL. Some studies showed that patients with frequent exacerbations had a significantly lower QOL than patients with less frequent exacerbations63. Bernhard et al.64 reported that changes in HRQOL were more dependent on the frequency of exacerbation than on FEV1 and DLCO decline. Hospitalization also increased the financial burden and reduced QOL65. Hospitalization among COPD patients could reduce their QOL due to physical, psychological, social life, and economic reasons.

Some limitations were found in this study that could impact the results and interpretations. First, with the nature of a cross-sectional study that assesses both exposures and outcomes at the same time, quality of life might not be the exact consequence of the preceding factors. Good QOL among individuals might be the integrated outcome of many factors, especially living environment and family relations, which were not measured in our study. Second, the size of the study sample obtained from the standard formula for a cross-sectional study might impact the generalizability of the results to the general population. Last, using telephone calls to collect data might impact the completeness of the data and the quality of the data because physical body language could not be evaluated.

Conclusion

A large proportion of COPD patients living in Zhejiang Province, China, suffer from poor QOL. Several personal traits and the unaffordable cost of treatment are the major factors contributing to poor QOL among COPD patients. To improve QOL among COPD patients, public health policy-makers must develop a proper channel to increase accessibility to health care services, including affordable health insurance. Health institutes must consider supportive ways to provide medical services for COPD patients. Implementing measures to help COPD patients obtain a better job and higher income for family members is one of the challenges to ensure that COPD patients will be able to access medical care and have good QOL.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- SGRQ:

-

St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- IOC:

-

Item-objective congruence

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- FEV1:

-

Forced expiratory volume in one second

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

References

Park, H. Y. et al. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on mortality: a large national cohort study. Respirology 25(7), 726–734. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.13678 (2020).

Agusti, A. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2022 report). Available from: https://goldcopd.org/2022-gold-reports-2/. Accessed 20 May 2022.

Chai, C. S. et al. Clinical phenotypes and heath-related quality of life of COPD patients in a rural setting in Malaysia—a cross-sectional study. BMC Pulm. Med. 20(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-020-01295-4 (2020).

Kwon, H. Y. & Kim, E. Factors contributing to quality of life in COPD patients in South Korea. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 11, 103 (2016).

Office of the State Council. Notice of the General Office of the State Council on Printing and Distributing China's Mid- and Long-Term Plan for the Prevention and Treatment of Chronic Diseases (2017–2025). Available from: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2017-02/14/content_5167886.htm. Accessed on 20 May 2022.

Fang, L. et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: A nationwide prevalence study. Lancet Respir. Med. 6(6), 421–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30103-6 (2018).

Wang, C. Epidemiological survey and analysis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among urban residents in Jinan. Available from: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/thesis/Y1790368. Accessed on 20 May 2022.

Yin, P. et al. A subnational analysis of mortality and prevalence of COPD in China from 1990 to 2013: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2013. Chest. 150(6), 1269–1280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2016.08.1474 (2016).

Stellefson, M., Paige, S. R., Barry, A. E., Wang, M. Q. & Apperson, A. Risk factors associated with physical and mental distress in people who report a COPD diagnosis: Latent class analysis of 2016 behavioral risk factor surveillance system data. Int. J. Chronic Obstructive Pulm. Dis. 14, 809. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S194018 (2019).

Yin, P. et al. The burden of COPD in China and its province: Findings from the global burden of disease study 209. Front. Public Health. 10, 859499. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.859499 (2022).

Von Leupoldt, A. & Janssens, T. Could targeting disease specific fear and anxiety improve COPD outcomes?. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 10(8), 835–837 (2016).

Xu, G., Fan, G. & Niu, W. COPD awareness and treatment in China. Lancet Respir. Med. 6(8), e38. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30200-5 (2018).

Zeng, Y., Jiang, F., Chen, Y., Chen, P. & Cai, S. Exercise assessments and trainings of pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD: A literature review. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 13, 2013. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S167098 (2018).

Zhu, B., Wang, Y., Ming, J., Chen, W. & Zhang, L. Disease burden of COPD in China: A systematic review. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 13, 1353. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S161555 (2018).

Zhou, T., Guan, H., Yao, J., Xiong, X. & Ma, A. The quality of life in Chinese population with chronic non-communicable diseases according to EQ-5D-3L: A systematic review. Qual. Life Res. 27(11), 2799–2814. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1928-y (2018).

Li, J. What should COPD patients do during the "anti-pandemic" period". Family Medicine: Second Half Month (2020).

Yang, H., Chen, S., Zheng, P. & Li, W. W. Survey on the prevalence and risk factors of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among residents in Yongjia County. Zhejiang Prev. Med. 28(6), 4 (2016).

Lv, X., Chen, W., Liu, J., Yang, Q., Fang, Z., Zhuang, Y., et al. Epidemiological investigation and risk factor analysis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Jiaxing City, Zhejiang Province. Chin. J. Evid. Based Med. 15(6), 5 (2015). Available from: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/zgxzyx201506003. Accessed on 20 May 2022.

Office for National Statistics website. China's economic performance in the first three quarters of 2022. Available from: http://www.gov.cn/zhuanti/2022sjdjjsj/index.htm. Accessed on 24 October 2022.

Yoon, H. K., Park, Y. B., Rhee, C. K., Lee, J. H. & Oh, Y. M. Summary of the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease clinical practice guideline revised in 2014 by the Korean academy of tuberculosis and respiratory disease. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 80(3), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.4046/trd.2017.80.3.230 (2017).

Wang, M., Zhong, J. M., Fang, L. & Wang, H. Prevalence and associated factors of smoking in middle and high school students: a school-based cross-sectional study in Zhejiang Province, China. BMJ Open. 6(1), e010379. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010379 (2016).

Woldeamanuel, G. G., Mingude, A. B. & Geta, T. G. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and its associated factors among adults in Abeshge District, Ethiopia: A cross sectional study. BMC Pulm. Med. 19(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-019-0946-z (2019).

Atkinson, R. W. et al. Long-term exposure to outdoor air pollution and the incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a national English cohort. Occup. Environ. Med. 72(1), 42–48. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2014-102266 (2015).

Pourhoseingholi, M. A., Vahedi, M. & Rahimzadeh, M. Sample size calculation in medical studies. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench. 6(1), 14 (2013).

Bi, J. Research on the correlation between COPD patients' perception of chronic disease management, self-management ability and quality of life. 2017. Available from: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD201702&filename=1017081287.nh. Accessed on 24 October 2022.

Jones, P. W., Quirk, F. H. & Baveystock, C. M. The St George’s respiratory questionnaire. Respir. Med. 85, 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0954-6111(06)80166-6 (1991).

Altman, D. G. & Bland, J. M. Statistics notes: quartiles, quintiles, centiles, and other quantiles. BMJ. 309(6960), 996–996. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.309.6960.996 (1994).

Gao, Y. H. et al. Validation of the Mandarin Chinese version of the Leicester Cough Questionnaire in bronchiectasis. Int. J. Tuberculosis Lung Dis. 18(12), 1431–1437. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.14.0195 (2014).

Turner, R. C. & Carlson, L. Indexes of item-objective congruence for multidimensional items. Int. J. Test. 3(2), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327574IJT0302_5 (2003).

Health Commission website. Healthy China Action (2019–2030). Available at: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-07/15/content_5409694.htm. Accessed on 21 May 2022.

National Bureau of Statistic. China Statistical Yearbook. Available from: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/. Accessed on 20 May 2022.

Kupcewicz, E. & Abramowicz, A. Assessment of quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Hygeia Public Health. 49(4), 805–812 (2014).

Wheaton, A. G., Cunningham, T. J., Ford, E. S. & Croft, J. B. Employment and activity limitations among adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—United States, 2013. Morb. Mort. Week. Rep. 64(11), 289 (2015).

Rai, K. K., Adab, P., Ayres, J. G. & Jordan, R. E. Systematic review: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and work-related outcomes. Occup. Med. 68(2), 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqy012 (2018).

Parekh, T. M. et al. The association of low income and high stress with acute care use in COPD patients. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. J. COPD Found. 7(2), 107. https://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.7.2.2019.0165 (2020).

Parekh, T. M. et al. Factors influencing decline in quality of life in smokers without airflow obstruction: The COPDGene study. Respir. Med. 161, 105820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2019.105820 (2020).

Politis, A., Ioannidis, V., Gourgoulianis, K. I., Daniil, Z. & Hatzoglou, C. Effects of varenicline therapy in combination with advanced behavioral support on smoking cessation and quality of life in inpatients with acute exacerbation of COPD, bronchial asthma, or community-acquired pneumonia: A prospective, open-label, preference-based, 52-week, follow-up trial. Chronic Respir. Dis. 15(2), 146–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/14799723177401 (2018).

Örnek, T. et al. Clinical factors affecting the direct cost of patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Med. Sci. 9(4), 285. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.4039 (2012).

Pandey, R. A., Chalise, H. N., Shrestha, A. & Ranjit, A. Quality of life of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease attending a Tertiary Care Hospital, Kavre Nepal. Kathmandu Univ. Med. J. 19(2), 180–185. https://doi.org/10.3126/kumj.v19i2.49642 (2021).

Yun, W. J. et al. Household and area income levels are associated with smoking status in the Korean adult population. BMC Public Health. 15, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1365-6 (2015).

Kwon, H. Y. & Kim, E. Factors contributing to quality of life in COPD patients in South Korea. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 11, 103. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S90566 (2016).

Wang, J., Li, P. & Wen, J. Impacts of the zero mark-up drug policy on hospitalization expenses of COPD inpatients in Sichuan province, western China: An interrupted time series analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 20(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05378-0 (2020).

Fang, X., Wang, X. & Bai, C. COPD in China: The burden and importance of proper management. Chest. 139(4), 920–929. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.10-1393 (2011).

Li, M. et al. Factors contributing to hospitalization costs for patients with COPD in China: A retrospective analysis of medical record data. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 13, 3349. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S175143 (2018).

Kim, J. K. et al. Factors associated with exacerbation in mild-to-moderate COPD patients. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 11, 1327–1333. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S105583 (2016).

Lee, H. et al. Different impacts of respiratory symptoms and comorbidities on COPD-specific health-related quality of life by COPD severity. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 12, 3301. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S145910 (2017).

Goërtz, Y. M. et al. Fatigue is highly prevalent in patients with COPD and correlates poorly with the degree of airflow limitation. Therap. Adv. Respir. Dis. 13, 128. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753466619878 (2019).

Miravitlles, M. & Ribera, A. Understanding the impact of symptoms on the burden of COPD. Respir. Res. 18(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-017-0548-3 (2017).

Skloot, G. S. The effects of aging on lung structure and function. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 33(4), 447–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2017.06.001 (2017).

Divo, M. et al. Comorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 186(2), 155–161. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201201-0034OC (2012).

Jankowska-Polańska, B., Kasprzyk, M., Chudiak, A. & Uchmanowicz, I. Effect of disease acceptance on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Adv. Respir. Med. 84(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.5603/PiAP.a2015.0079 (2016).

Yazar, E., Sahin, F., Aynaci, E., Yildiz, P., Ozgul, A., & Yilmaz, V. Is there any relationship between the duration to diagnosis of COPD and severity of the disease? Eur. Respir. J. Available form: https://erj.ersjournals.com/. Accessed on 20 May 2022.

Sigurgeirsdottir, J., Halldorsdottir, S., Arnardottir, R. H., Gudmundsson, G. & Bjornsson, E. H. COPD patients’ experiences, self-reported needs, and needs-driven strategies to cope with self-management. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 14, 1033. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S201068 (2019).

Apps, L. D. et al. A qualitative study of patients’ experiences of participating in SPACE for COPD: A Self-management Programme of Activity, Coping and Education. ERJ Open Res. 3(4), 1. https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00017-2017 (2017).

Alahmari, A. D. et al. Physical activity and exercise capacity in patients with moderate COPD exacerbations. Eur. Respir. J. 48(2), 340–349. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01105-2015 (2016).

Martinez Rivera, C. et al. Factors associated with depression in COPD: A multicenter study. Lung. 194(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-016-9862-7 (2016).

Matte, D. L. et al. Prevalence of depression in COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled studies. Respir. Med. 117, 154–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2016.06.006 (2016).

Pumar, M. I. et al. Anxiety and depression—Important psychological comorbidities of COPD. J. Thorac. Dis. 6(11), 1615. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.09.28 (2014).

Mohsen, S., Hanafy, F. Z., Fathy, A. A. & El-Gilany, A. H. Nonadherence to treatment and quality of life among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lung India Off. Organ Indian Chest Soc. 36(3), 193. https://doi.org/10.4103/lungindia.lungindia_340_18 (2019).

Huang, J. Analysis on direct economic burden of hospitalized patients with COPD and its influencing factors in a three-level hospital in Beijing. Med. Soc. 28(7), 19–22 (2015).

Xiang, Y. T. et al. Quality of life in older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Hong Kong: A case-control study. Perspect. Psychiatric Care. 51(2), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12073 (2015).

Takechi, Y. Intervention for COPD exacerbation-how to prevent and treat COPD exacerbation?. Cancer Chemother. 43(Suppl 1), 61–63 (2016).

Hurst, J. R. et al. Understanding the impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations on patient health and quality of life. Eur. J. Int. Med. 73, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2019.12.014 (2020).

Bernhard, N. et al. Deterioration of quality of life is associated with the exacerbation frequency in individuals with alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency–analysis from the German registry. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 12, 1427. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S130925 (2017).

Walters, J. A., Tan, D. J., White, C. J. & Wood-Baker, R. Different durations of corticosteroid therapy for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 3, 1. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006897.pub4 (2018).

Acknowledgements

All participants in this study are gratefully acknowledged. We also express our gratitude to Mae Fah Luang University and all the hospitals that made this study possible.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from Mae Fah Luang University. The funding body did not play any role in the design of the study, collection, analysis and interpretation of data or in writing of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YY, SK, TA, and KN designed the study, collected data, analyzed data, drafted the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ying, Y., Khunthason, S., Apidechkul, T. et al. Influencing factors of good quality of life among chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients living in Zhejiang Province, China. Sci Rep 14, 8687 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-59289-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-59289-9

Keywords

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.