Abstract

The association between high blood pressure and fracture showed obvious discrepancies and were mostly between hypertension with future fracture, but rarely between fracture and incident hypertension. The present study aims to investigate the associations of hypertension with future fracture, and fracture with incident hypertension. We included adult participants from the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS) prospective cohort in 1997–2015 (N = 10,227), 2000–2015 (N = 10,547), 2004–2015 (N = 10,909), and 2006–2015 (N = 11,121) (baseline in 1997, 2000, 2004, 2006 respectively and outcome in 2015). Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs. In the analysis of the association between hypertension and future fracture, the adjusted HRs (95% CIs) were 1.34 (0.95–1.90) in 1997–2015, 1.40 (1.04–1.88) in 2000–2015, 1.32 (0.98–1.78) in 2004–2015, and 1.38 (1.01–1.88) in 2006–2015. In the analysis of the association between fracture and incident hypertension, the adjusted HRs (95% CIs) were 1.28 (0.96–1.72) in 1997–2015, 1.18 (0.94–1.49) in 2000–2015, 1.12 (0.89–1.40) in 2004–2015, and 1.09 (0.85–1.38) in 2006–2015. The present study showed that hypertension history was associated with increased risk of future fracture, but not vice versa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bone fracture and hypertension are both closely related with aging, and linking through the association between osteoporosis and arterial calcification1. Fractures in the elderly are mainly caused by osteoporosis (commonly seen in people aged over 50 years2,3); arterial calcification, as a very harmful kind of ectopic calcification, may cause arterial stiffening4, which was leading to blood pressure increase and hypertension5,6. Osteoporosis and arterial stiffening have been proved to be closely associated with each other7,8,9. Osteoporosis and arterial calcification are sharing the common molecular mechanisms, in which calcium is loss from bone tissue and ectopic deposition in the arteries10,11. Fracture resulting from osteoporosis and hypertension are supposed to be related with each other, even predictor for each other.

Previous studies of the association between hypertension and fracture showed obvious discrepancies, and were mostly focused on the association between hypertension with future fracture, but rarely on the association between fracture and incident hypertension. In the analysis of the association between hypertension with future fracture, cross-sectional12,13 and case-control14,15,16,17 studies showed significantly positive relationships, however, cohort studies18,19 reported non-significant relationships in male or both genders. In the present study, we will evaluate the associations of hypertension with future fracture and fracture with incident hypertension in a natural population from the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS) cohort. CHNS is a prospective study that includes multiple ages and cohorts across nine diverse provinces and ten rounds of surveys between 1989 and 2015. It is a large-scale, longitudinal study in China, and allows the researchers to understand the relationships between diseases and risk factors under normal circumstances20.

Methods

Study population

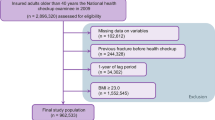

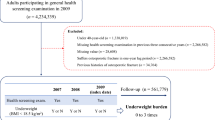

The current study used the longitudinal data from the CHNS. The CHNS is an open, prospective cohort study in China, which have completed 10 rounds of surveys in 1989, 1991, 1993, 1997, 2000, 2004, 2006, 2009, 2011, and 2015. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Survey procedures have been described in more detail elsewhere20,21,22. From 1997, the information of bone fracture was recorded, and we analyzed the associations of hypertension with future fracture (Fig. 1), and fracture with incident hypertension (Supplemental Fig. 1) in participants with age ≥ 18 years in 1997–2015 (baseline in 1997 and outcome in 2015), 2000–2015, 2004–2015, and 2006–2015. Inclusion criteria: participants from the CHNS with age ≥ 18 years at baselines, had clear history of hypertension and fracture, and those with missing history of hypertension or fracture were excluded. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital Affiliated to Capital Medical University in China. The study was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Covariates

Demographic and lifestyle information was obtained through questionnaires, including birth year, gender, diseases history, physical activity, smoking status, and alcohol consumption. Baseline age was calculated as the difference between baseline year and the birth year, and participants with baseline age < 18 years were excluded. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared, and body weight and height were measured by well-trained investigators who followed standard measuring procedures. Blood pressure (BP) was measured three times using standard mercury sphygmomanometers by experienced physicians. The average of the three BP measures was used in analyses. Physical activity was estimated from self-reported 7-day recalls of occupational, transportation, domestic, and leisure activities (the International Physical Activity Questionnaires [IPAQ] include the conversion and classification standard of physical activity), and divided into low and high activity level (low < 5000 MET minutes/week, high ≥ 5000 MET minutes/week). Baseline diabetes history, smoking, and alcohol consumption were recorded from self-reported histories.

In the analysis of the associations between BP values and future fracture, we used mean BP values at each baseline (mean values of BP in 1989, 1991, 1993 and 1997 for 1997–2015; mean values of BP in 1989, 1991, 1993, 1997 and 2000 for 2000–2015; mean values of BP in 1989, 1991, 1993, 1997, 2000 and 2004 for 2004–2015; mean values of BP in 1989, 1991, 1993, 1997, 2000, 2004 and 2006 for 2006–2015), and BP included systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), pulse pressure (PP) (PP = SBP-DBP), and mean arterial pressure (MAP) (MAP = DBP + 1/3 PP).The missing values were excluded.

Outcome

Hypertension was defined as a self-reported diagnosis of hypertension, current use of antihypertensive medication and BP measured of more than 140/90 mmHg. Fracture was defined as a self-reported fracture history. In the analysis of association between hypertension and future fracture, bone fracture was the primary outcome and recorded from the baseline year (not included) till 2015, and a total of 16,497 participants were recorded clear history of fracture till 2015 (Fig. 1); In the analysis of association between fracture and incident hypertension, hypertension was the primary outcome and recorded from the baseline year (not included) till 2015, and a total of 17,499 participants were recorded clear history of hypertension till 2015 (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Statistical analyses

We conducted all statistical analyses using R statistical software version 4.2.0. Continuous variables with normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and compared by two-sample t-test, while those with non-normal distributed were expressed as quartiles and compared by Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and numbers, and compared using the chi-square test. Cox regression models were assessed using the proportional hazards (PH) assumption. Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses were used to evaluate the associations of hypertension with future fracture, and fracture with incident hypertension. And we included age, gender, BMI, physical activity, diabetes history, smoking, alcohol consumption in the multivariable model. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and P-values of 0.05 were considered to be statistically.

Results

The present study included two parts: (1) analysis of the association between hypertension and future fracture, and (2) analysis of the association between fracture and incident hypertension. Both of the two parts were carried out in 1997–2015, 2000–2015, 2004–2015, and 2006–2015 (baseline in 1997, 2000, 2004, 2006 and outcome in 2015). The population characteristics in the analysis of the association between hypertension and future fracture was shown in Table 1. In this natural population, male made up nearly half (46.8–47.0%); mean age was increasing as baseline year moving forward (38.4–43.7 years); mean BMI was in an ideal range (23.2–23.5 kg/m2); the prevalence of diabetes was relatively low (0.5–1.3%); hypertension prevalence ranged from 1.6 to 5.8%; and the estimated annual incidences of fracture were 547, 524, 483, and 439 cases/per 100,000 people in baseline 1997, 2000, 2004, and 2006, respectively. To show the age distribution, the population was divided into four age categories: < 30, 30–40 (not included), 40–50 (not included), ≥ 50 years, in which participants proportions were close to 1/4 in each category in different baselines. As the baseline year moving forward, participants proportions in the higher age categories were increasing. The population characteristics in the analysis of the association between fracture and incident hypertension was shown in Supplemental Table 1. Demographic and lifestyle information was similar to the above. The estimated annual incidences of hypertension were 1802, 1809, 1728, and 1527 cases/per 100,000 people, respectively.

In univariate Cox regression analysis, hypertension history was associated with increased risk of future fracture in 1997–2015 (HR = 2.57, 95% CI 1.83–3.59, P < 0.001), 2000–2015 (HR = 2.59, 95% CI 1.96–3.43, P < 0.001), 2004–2015 (HR = 2.45, 95% CI 1.86–3.24, P < 0.001), and 2006–2015 (HR = 2.36, 95% CI 1.77–3.14, P < 0.001). After adjusting for age, the association of hypertension and future fracture seemed to be changed but still of statistical significance in 1997–2015 (HR = 1.47, 95% CI 1.04–2.07, P = 0.028), 2000–2015 (HR = 1.54, 95% CI 1.16–2.05, P = 0.003), 2004–2015 (HR = 1.40, 95% CI 1.05–1.87, P = 0.022), and 2006–2015 (HR = 1.37, 95% CI 1.02–1.85, P = 0.039). After adjusting for age, gender, BMI, physical activity, hypertension, diabetes, smoking and alcohol consumption, the association between hypertension and future fracture was still significant in 2000–2015 (HR = 1.40, 95% CI 1.04–1.88, P = 0.024) and 2006–2015 (HR = 1.38, 95% CI 1.01–1.88, P = 0.045), and not significant in 1997–2015 (HR = 1.34, 95% CI 0.95–1.90, P = 0.097) and 2004–2015 (HR = 1.32, 95% CI 0.98–1.78, P = 0.071) (Table 2). In multivariate Cox regression analysis, aging, female, high physical activity, smoking and alcohol consumption were not significantly associated with the risk of future fracture (Supplemental Table 2).

In the analysis of the associations between BP values and future fracture, we used mean values of BP in 1989, 1991, 1993 and 1997 for baseline 1997, mean values of BP in 1989, 1991, 1993, 1997 and 2000 for baseline 2000, mean values of BP in 1989, 1991, 1993, 1997, 2000 and 2004 for baseline 2004, and mean values of BP in 1989, 1991, 1993, 1997, 2000, 2004 and 2006 for baseline 2006. The missing BP values were excluded. In univariate Cox regression analysis, increase of mean SBP values were associated with increased risk of future fracture in 1997–2015 (every 10 mmHg increase of SBP, HR = 1.19, 95% CI 1.12–1.26, P < 0.001), 2000–2015 (every 10 mmHg increase of SBP, HR = 1.23, 95% CI 1.16–1.31, P < 0.001), 2004–2015 (every 10 mmHg increase of SBP, HR = 1.17, 95% CI 1.10–1.25, P < 0.001), and 2006–2015 (every 10 mmHg increase of SBP, HR = 1.21, 95% CI 1.12–1.30, P < 0.001). After multivariate adjusted, the association between mean SBP values and future fracture was still significant in 1997–2015 (every 10 mmHg increase of SBP, HR = 1.07, 95% CI 1.01–1.14, P = 0.032) and 2000–2015 (every 10 mmHg increase of SBP, HR = 1.08, 95% CI 1.01–1.16, P = 0.024), and not significant in 2004–2015 and 2006–2015. Mean DBP and MAP increases were also associated with increased risk of future fracture in univariate Cox regression analysis, but the association became non-significant in multivariate regression. In univariate Cox regression analysis, increase of mean PP values were associated with increased risk of future fracture in 1997–2015 (every 5 mmHg increase of PP, HR = 1.14, 95% CI 1.08–1.19, P < 0.001), 2000–2015 (every 5 mmHg increase of PP, HR = 1.17, 95% CI 1.12–1.23, P < 0.001), 2004–2015 (every 5 mmHg increase of PP, HR = 1.13, 95% CI 1.07–1.19, P < 0.001), and 2006–2015 (every 5 mmHg increase of PP, HR = 1.17, 95% CI 1.11–1.24, P < 0.001). After multivariate adjusted, the association between mean PP values and future fracture was still significant in 1997–2015 (every 5 mmHg increase of PP, HR = 1.06, 95% CI 1.01–1.12, P = 0.014), 2000–2015 (every 5 mmHg increase of PP, HR = 1.08, 95% CI 1.02–1.13, P = 0.006), and 2006–2015 (every 5 mmHg increase of PP, HR = 1.08, 95% CI 1.01–1.16, P = 0.022), and not significant in 2004–2015 (Table 3).

In the analysis of association between fracture and incident hypertension, bone fracture history was associated with increased risk of incident hypertension in univariate Cox regression analysis (for 1997–2015, HR = 1.97, 95% CI 1.47–2.64, P < 0.001; for 2000–2015, HR = 1.68, 95% CI 1.35–2.11, P < 0.001; for 2004–2015, HR = 1.47, 95% CI 1.18–1.84, P < 0.001; for 2006–2015, HR = 1.48, 95% CI 1.17–1.87, P < 0.001), but the association became non-significant after adjusting for age only, and still non-significant in multivariate regression (Table 4).

Discussion

The present study has an intriguing finding that hypertension history was associated with increased risk of future fracture, but fracture was not significantly associated with increased risk of incident hypertension after adjusting for age only, and still non-significant in the multivariate regression.

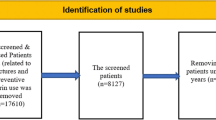

In the studies of association between hypertension and fracture risk, cross-sectional studies of health check-up populations and hospitalized patients reported that hypertension was associated with increased risk of fracture12,13. Several case–control studies, by tracing cardiovascular diseases hospitalization prior to fracture, showed that hypertension was associated with increased risk of fracture14,15,16. However, a case–control study17 with a small sample size reported hypertension was associated with increased risk of hip fracture only in women but not in men. A prospective cohort study18 with a small sample size also showed hypertension was associated with increased risk of hip fracture only in women but not in men. Another cohort study19 showed hypertension was not associated with future fracture risk. Obvious discrepancies exist in the reported finding above, so we carried out a systematic review of the published articles, and the results showed hypertension was associated with increased risk of future fracture in overall studies (pooled OR = 1.40, 95% CI 1.23–1.60; I2 = 72%, P < 0.01) and cohort studies (pooled OR = 1.28, 95% CI 1.09–1.50; I2 = 87%, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2). In the research of association between fracture and hypertension risk, a retrospective case–control study from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed that fracture was associated with increased risk of hypertension in the crude model, but became non-significant after multivariable adjusted, which is consistent with the present study. The analysis of the present study and previous studies showed that hypertension was associated with increased risk of future fracture, but not vice versa.

Bone fracture and hypertension are diseases both related with aging. Osteoporotic fracture is an influential health issue in the elderly, which will result in substantial bone-associated morbidities and increased mortality2. In fact, osteoporosis is commonly detected by X-ray-based imaging in people aged over 50 years3. Fractures in the young are more likely to be non-osteoporotic fractures, however, chronic kidney diseases and endocrine abnormalities will result in osteoporosis in the young23,24. Hypertension is also an age-related disease. A certain number of studies6,9 have discussed the association between hypertension and arterial stiffening, that arterial stiffening may antedate and contribute to the development of hypertension25. Arterial medial calcification is the pathophysiological mechanism of arterial stiffening. Generalized arterial calcification of infancy (GACI) will present hypertension after birth26. Patients with hypertension are supposed to have arterial calcification, which may or may not be detected. Arterial calcification is a very harmful kind of ectopic calcification, which is sharing the common molecular mechanisms with osteoporosis11. In osteoporosis and arterial calcification, calcium is loss from bone tissue and ectopic deposition in the arteries. Based on the results of the present study, we supposed that, when arterial stiffening is leading to hypertension, bone tissue may already have osteoporotic changes, which may or may not be detected. In the follow-up, osteoporosis causes fragility fractures. That is why hypertension may predict future fracture. But on the other hand, fractures are not all osteoporosis-caused. Osteoporosis occurs as arterial calcification happens. Osteoporosis has been proved to be associated with hypertension risk27. But fracture may not predict incident hypertension.

The present study has some limitations: first, there are no bone mineral density or other biomarker to evaluate osteoporosis in CHNS, thus, it is difficult to show the effect of osteoporosis in the association between hypertension and fracture, and we can only speculate it from the results of other studies; second, in this natural population, fracture incidence is too low for subgroup analysis, and we can’t perform analysis in different ages or other groups.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Tap, L. et al. Unraveling the links underlying arterial stiffness, bone demineralization, and muscle loss. Hypertension. 76, 629–639 (2020).

Collaborators GBDF. Global, regional, and national burden of bone fractures in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2, e580–e592 (2021).

Clynes, M. A. et al. The epidemiology of osteoporosis. Br. Med. Bull. 133, 105–117 (2020).

Durham, A. L., Speer, M. Y., Scatena, M., Giachelli, C. M. & Shanahan, C. M. Role of smooth muscle cells in vascular calcification: Implications in atherosclerosis and arterial stiffness. Cardiovasc. Res. 114, 590–600 (2018).

Kaess, B. M. et al. Aortic stiffness, blood pressure progression, and incident hypertension. JAMA. 308, 875–881 (2012).

Dernellis, J. & Panaretou, M. Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of progression to hypertension in nonhypertensive subjects. Hypertension. 45, 426–431 (2005).

Jaalkhorol, M. et al. Low bone mineral density is associated with an elevated risk of developing increased arterial stiffness: A 10-year follow-up of Japanese women from the Japanese Population-based Osteoporosis (JPOS) cohort study. Maturitas. 119, 39–45 (2019).

El-Bikai, R. et al. Association of age-dependent height and bone mineral density decline with increased arterial stiffness and rate of fractures in hypertensive individuals. J Hypertens. 33, 727–735 (2015). (discussion 735).

Raggi, P., Bellasi, A., Ferramosca, E., Block, G. A. & Muntner, P. Pulse wave velocity is inversely related to vertebral bone density in hemodialysis patients. Hypertension. 49, 1278–1284 (2007).

De Mare, A., Opdebeeck, B., Neven, E., D’Haese, P. C. & Verhulst, A. Sclerostin protects against vascular calcification development in mice. J. Bone Miner. Res. 37, 687–699 (2022).

Wei, X. et al. Understanding the stony bridge between osteoporosis and vascular calcification: Impact of the FGF23/Klotho axis. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2021, 7536614 (2021).

Wada, H., Hirano, F., Kuroda, T. & Shiraki, M. Breast arterial calcification and hypertension associated with vertebral fracture. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 12, 330–335 (2012).

Xu, B. et al. Cardiovascular disease and hip fracture among older inpatients in Beijing, China. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 493696 (2013).

Gerber, Y. et al. Cardiovascular and noncardiovascular disease associations with hip fractures. Am. J. Med. 126(169), e19-26 (2013).

Sennerby, U., Farahmand, B., Ahlbom, A., Ljunghall, S. & Michaelsson, K. Cardiovascular diseases and future risk of hip fracture in women. Osteoporos. Int. 18, 1355–1362 (2007).

Vestergaard, P., Rejnmark, L. & Mosekilde, L. Hypertension is a risk factor for fractures. Calcif. Tissue Int. 84, 103–111 (2009).

Perez-Castrillon, J. L. et al. Hypertension as a risk factor for hip fracture. Am. J. Hypertens. 18, 146–147 (2005).

Yang, S., Nguyen, N. D., Center, J. R., Eisman, J. A. & Nguyen, T. V. Association between hypertension and fragility fracture: A longitudinal study. Osteoporos. Int. 25, 97–103 (2014).

Tran, T. et al. A risk assessment tool for predicting fragility fractures and mortality in the elderly. J. Bone Miner. Res. 35, 1923–1934 (2020).

Zhang, B., Zhai, F. Y., Du, S. F. & Popkin, B. M. The China Health and Nutrition Survey, 1989–2011. Obes. Rev. 15(Suppl 1), 2–7 (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. Waist circumference change is associated with blood pressure change independent of BMI change. Obesity (Silver Spring). 28, 146–153 (2020).

Popkin, B. M., Du, S., Zhai, F. & Zhang, B. Cohort profile: The China Health and Nutrition Survey–monitoring and understanding socio-economic and health change in China, 1989–2011. Int J Epidemiol. 39, 1435–1440 (2010).

Sakka, S. D. Osteoporosis in children and young adults. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 36, 101776 (2022).

Rozenberg, S. et al. How to manage osteoporosis before the age of 50. Maturitas. 138, 14–25 (2020).

Mitchell, G. F. Arterial stiffness and hypertension: Chicken or egg?. Hypertension. 64, 210–214 (2014).

Ramirez-Suarez, K. I. et al. Longitudinal assessment of vascular calcification in generalized arterial calcification of infancy. Pediatr. Radiol. 52, 2329–2341 (2022).

Park, J. S. et al. Parathyroid hormone, calcium, and sodium bridging between osteoporosis and hypertension in postmenopausal Korean women. Calcif. Tissue Int. 96, 417–429 (2015).

Funding

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170335, 81800304).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiang-Peng Du, Mei-Liang Zheng and Mei-Li Zheng wrote the main manuscript text, Xiang-Peng Du prepared tables and Xin-Chun Yang prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, XP., Zheng, ML., Yang, XC. et al. High blood pressure is associated with increased risk of future fracture, but not vice versa. Sci Rep 14, 8005 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58691-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58691-7

Keywords

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.