Abstract

The knowledge and attitudes of health care providers were limited as reviewed in many studies. Attitudes and knowledge about pre-exposure prophylaxis among healthcare providers have not been investigated in Ethiopia even though pre-exposure prophylaxis is a novel healthcare topic. The aim was to assess knowledge, attitudes, and associated factors towards pre-exposure prophylaxis among healthcare providers in Gojjam health facilities, North West Ethiopia, 2022. An institutional-based cross-sectional study was conducted from June 1–30 among 410 healthcare providers in public health facilities in the East Gojjam zone. A simple random sampling technique was used to recruit the required study participants. The statistical program EPI Data version 4.6 was used to enter the data, and statistical packages for Social science version 25 was used for analysis. Variables with a p-value less than 0.25 in the bivariable analysis were included in the multivariable logistic regression analysis. Statistical significance was determined with a p-value less than 0.05. The good knowledge and the favorable attitude of healthcare providers toward HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis were 55.7% (50.6–60.2%) and 60.2% (55.0–65.0%) respectively. male participant (AOR 1.67; 95% CI (1.01–2.55), service year ≥ 10 years (AOR 2.52; 95% CI (1.23–5.17), favorable attitudes (AOR 1.92; 95%CI (1.25–2.95), and providers good sexual behavior (AOR 1.85; 95%CI (1.21–2.82) were significantly associated with the good knowledge, and training (AOR 2.15; 95% CI (1.23–3.76), reading the guideline (AOR 1.66; 95% CI (1.02–2.70), and good knowledge (AOR 1.78; 95% CI (1.16–2.75) was significantly associated with the favorable attitudes. In general, the finding of this study shows that the knowledge and attitudes of healthcare providers were low. Since this is a new initiative their knowledge is lower than their attitudes. Male, service year 10 years, and good provider sexual behavior were factors significantly associated with good knowledge. Training, reading the guidelines, and good knowledge were factors significantly associated with a favorable attitudes. As a result, healthcare facilities intervention programs and strategies better target these factors to improve the knowledge and attitudes of healthcare providers. Preparing training programs to enhance knowledge and attitudes towards PrEP is recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background

HIV/AIDS is among chronic infectious diseases and the primary global burden of diseases1. Currently, there is a new strategy to prevent newly acquired infection of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) for people exposed to HIV/AIDS by once-daily taking medications called pre-exposure prophylaxis. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is an effective prevention against HIV, approved by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2015, and by the United States Food and Drug Administration (UFDA) in 20122,3. Ethiopia approved tenofovir (TDF)/ lamivudine (3TC) HIV prevention and considered HIV PrEP as one of the six pillars for HIV prevention for HIV-negative people in 20194.

PrEP has been widely regarded as a biomedical prevention strategy for highly vulnerable population groups to contracting HIV5. Several clinical trials have demonstrated unequivocally the effectiveness of a combination of TDF/3TC fixed-dose combination used as per the WHO recommendation in reducing the risk of HIV transmission6. The WHO has recently recommended its adoption as one of the strategies to combat new HIV infections among individuals at substantial risk of HIV (commercial sex workers and discordant)7. If taken daily by an HIV- negative individual, PrEP provides over 90% reduction in HIV acquisition8.

Several African countries have already approved guidelines for tenofovir plus emtricitabine, although Ethiopia approved tenofovir plus lamivudine-based PrEP for HIV prevention to individuals at substantial risk of HIV as part of combination HIV prevention despite key questions remain about how to identify and deliver PrEP to those in greatest need4,9,10,11. Throughout the continent, individuals in serodiscordant relationships and Sex workers are likely to benefit from the availability of PrEP. It has been estimated that at least three million individuals in Africa are likely to be eligible for PrEP according to WHO's criteria12.

Health Care professionals must be aware of and willing to administer PrEP to apply PrEP guidelines and effectively deliver PrEP to at-risk groups. Provider acceptability studies have been primarily undertaken in PrEP research studies in North America5,8,13,14. Understanding provider concerns and challenges to PrEP knowledge and attitudes in distinct geographical and cultural settings has the potential to increase PrEP coverage among critical populations, helping to achieve the overarching objective of regional and global HIV incidence reduction15.

Despite these developments, the use of PrEP among those at the highest risk of HIV acquisition has been slow. Until March 2022 only 2870 people in Ethiopia have received a prescription for PrEP out of 14,046 eligible PrEP users who attend health facilities. The estimated cumulative number of people to initiated PrEP was 16,000 to 17,000, this indicates that there is a huge gap between the eligible people and the access to PrEP16.

Different strategies have been implemented to cope with this problem in Ethiopia including USAIDS targets of 95–95–95, the HIV/AIDS strategic plan to end HIV transmission by 2030 and reduce HIV as a public health threat, an implementation manual for pre-exposure prophylaxis of HIV infection, also national comprehensive HIV care guideline recommends PrEP for clients at substantial risk of HIV infection4,17.

The Federal Ministry of Health 2019 released HIV-PrEP guidelines including oral tenofovir/ lamivudine fixed-dose as a PrEP for a person who has a risk but is not yet infected with HIV according to the clinical benefit of HIV-PrEP18.

Health providers that work in African countries have low knowledge of PrEP and the knowledge ranges from 3.5% in Tanzania to 67% in Kenya5,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. The magnitude of the attitudes of healthcare providers toward PrEP is not similar around the world. The pooled prevalence of providers' attitudes about PrEP is 66% in the USA, 70% in England, and 79 in Italy out of European countries6,23,26. Unlike European and American countries the attitudes of health providers in Africa is below 60% in Tanzania, Uganda, Botswana, and South Africa10,24.

HIV PrEP services should be given by a provider that has good knowledge and a favorable attitude. Despite this, if it is given by a provider with poor knowledge and unfavorable attitudes could have many consequences such as increased new HIV acquisition, poor patient adherence to ART medication, development of HIV drug resistance, decreased willingness to new PrEP users, decreased number of follow up patients, and an increase in the incidence of other sexually transmitted diseases14,27. It also decreases the satisfaction of substantial-risk individuals with PrEP service and decreases provider-to-user relationships28.

Providers who have poor knowledge and unfavorable attitudes still represent a significant barrier for substantial risk individuals seeking PrEP29,30,31. The knowledge and attitudes towards HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among health care providers working in health care facilities in Ethiopia have not yet been studied. Therefore, this study aims to assess the knowledge, attitudes and associated factors towards HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among healthcare providers working in East Gojjam zone health facilities.

Methodology

Study area, period, and design

A multi-institutional based cross-sectional study was conducted from June 1 to 30 in the East Gojjam zone, North West Ethiopia. The total number of healthcare work providers in the study area was 51832. Based on the Amhara Regional Health Bureau report there are eleven hospitals and 102 health centers under the zone33. Eleven hospitals and fifteen health centers are providing PrEP services for those substantial risk individuals34.

Population

The source populations were healthcare providers (physicians, health officers, nurses, and midwives) who were working in ART, VCT, and PMTCT in the East Gojjam zone public health facilities and The study populations of this study were healthcare providers (physicians, health officers, nurses, and midwives) who were working in ART, VCT, and PMTCT during the study period.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All Healthcare providers (physicians, health officers, nurses, and midwives) who were working in ART, VCT, and PMTCT during the study period were included in the study. HCPs who were sick and on annual leave at the time of data collection were excluded from the study.

Sample size determination

The sample size was determined by using a single population proportion formula with the assumption of 59% and 67% of the overall prevalence of knowledge and attitudes of healthcare workers towards HIV PrEP from the previous studies done in Kenya respectively25. 95% confidence level and 5% margin of error. Based on this study the actual sample size for the study was computed by using a single population proportion formula.

where n = sample size of the population, Z = critical value of 95% CI = 1.96, P = Proportion of knowledge or attitudes of PrEP taken as above (0.5) D = precision (marginal error) = 0.05.

The sample size of attitudes

The sample size of knowledge

Then, by adding 10% for possible non-response rate the total sample size by knowledge and attitudes was 410 and 379 respectively. The sample size for the third and fourth objectives was determined using Epi-info 7 software with the assumption of 95% CI, 5% margin of error, 80% power, and exposure to an unexposed ratio of 1:1 (Table 1).

Then, from the above list of sample sizes, the large sample is 410, and it was taken as the final sample of the population.

Sampling techniques

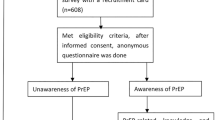

A simple random sampling technique was used to select the study participants after allocating participants from public health facilities by proportional allocation to the population. The list of health providers taken from the matron and chief medical officer was used as a sampling frame and study participants were selected by lottery method until 410 health providers from a total of 518 HCPs in the working area (Fig. 1).

Study variables

Dependent variables

Knowledge and attitudes of HCPs towards HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis.

Independent variables

Socio-demographic factors: sex, age, marital status, profession, and educational level.

Sexual risky behavioral factors: Ask about sexual activity, discuss sexual behavior, offer HIV test for adults who needs treatment, refer high-risk patients, and offer PrEP for high-risk individuals.

Work-related factors: Place of work, service year, working area/ward, availability of resources, history of working in PEP, Training, and the number of patients served per day.

Operational definitions, data collection tools, procedures, and techniques

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

PrEP is an evidence-based HIV risk-reduction intervention with two ART drug combinations (TDF/3TC) that is offered to commercial sex workers and serodiscordant couples at risk of acquiring HIV37.

Attitudes

The attitudes of healthcare providers were measured with standardized tool and who scored greater than or equal to the mean from the total attitudes-related questions were considered to have favorable attitudes towards PrEP. There are 13 attitudes-related questions that had a Likert scale scored 1, 2,3,4, and 5 for strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly agree respectively those who scored agree and strongly agree are considered to have favorable attitudes38.

Knowledge

Healthcare providers who answer ≥ 70% of total knowledge-related questions regarding PrEP have good knowledge whereas healthcare providers who scored below 70% of knowledge-related questions were considered as having poor knowledge36.

Behaviors/practices regarding providers’ HIV testing and pre-exposure prophylaxis

Someone is considered as having good Behaviors/practices regarding providers’ HIV testing and pre-exposure prophylaxis, at least if he/she answers often and always on a 5-point Likert scale from six questionnaires, and those who answered never, rarely, and sometimes were considered as having poor Behaviors/practices39.

Data were collected using a structured and pretested self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire and the consent form were prepared in English. The data were collected by 11 trained BSc degree nurses and were supervised by 3 MSc nurses and 2 public health professionals having previous experience in data collection. The data were collected using a simple random sampling technique by using a lottery method and approached privately on arrival without disturbing the routine working activity in the health facility. The objective of the study was explained to them using study-specific information and enough time was given to make an independent decision to participate in the study.

Data quality assurance and control

Data quality was controlled by giving training and appropriate supervision for data collectors. One day of training was provided to the data collectors and the supervisor on the aim of the study, how to use the questionnaire, how to approach study participants, and how to collect data and supervise.

The questionnaires were evaluated by three HIV/AIDS experts (a physician and an MSc nurse) before the data collection. The questionnaire was arranged based on the content validity index (CVI) format and sent to those experts via email to give their evaluation. Based on their responses I-CVI scores were calculated by dividing the expert agreement by the number of experts, and finally, the average of I-CVI scores across all items was computed. Based on this procedure the S-CVI was 0.86 for knowledge and 0.88 for attitudes-related questions. Which indicates the tool is acceptable.

A pretest was conducted on 5% (n = 21) of the total sample size at Finote Selam General Hospital. The reliability of the tool was checked before data collection with alpha coefficients for the knowledge, attitudes, and providers' sexual behavior scales of 0.739, 0.726, and 0.778, respectively. Continuous follow-up and supervision were also made by the principal investigator throughout the data collection period. A review was made to check the completeness of the questionnaire and corrections was made. Each questionnaire and data sheet was checked before the data entry. The data was entered daily for nearby sites and every week for those far sites and there was no identified major missing data.

Data processing and analysis

The data were checked for discrepancies and completeness. The data were entered using Epi-data version 4.6. Then the data were cleaned, coded, and analyzed using SPSS version 25. The Multicollinearity between each independent variable was checked and there was no correlation between the independent variables with the Variance inflation factor (VIF) with a maximum value of 2.3 and the Tolerance test with a minimum value of 43.6%.

Hosmer and Lemeshow's goodness of fit test was used to test the model adequacy using a p-value (p = 0.615) for knowledge and (P = 0.269) for attitudes model fit. Variables having a p-value < 0.25 in a bi-variable analysis were entered into a multivariable binary logistic regression model to adjust for possible confounders. P-value < 0.05 and odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval were considered as a measure of statistically significant variables in this study. The result was described and expressed by using tables, graphs, and narrative descriptions.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Debre Markos University, College of Health Sciences Ethical and Research review committee with an ethical clearance reference number of HSC/R/C/Ser/PG/Co/214/11/14. A formal letter of cooperation was written to eleven hospitals and other fifteen health centers. All methods were performed according to relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from each study participant. Data was kept anonymously in the distributed questionnaire to keep confidentiality.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of healthcare providers

A total of 397 healthcare providers were included in the study, giving a response rate of 96.8%. Of the total participants, 314 (79.1%) healthcare providers ranged from 25 to 34 years old with a mean age of 29.48 with SD ± 4.07 years. The majority of the participants 255 (64.2%), were married and 218 (54.9%) of the participants were male by sex. Regarding the profession of participants around 213 (53.7%) were nurses, and 290 (73.0%) participants were first-degree holders (Table 2).

Providers' work-related characteristics

Among 397 study participants, 205 (51.7%) participants were from the hospital, and 180 (45.3%) study participants were working in ART. 200 (50.4%) participants had work experience of 5 -10 years, but only 117 (29.5%) participants had received the training on PrEP. Two hundred sixty-eight (67.5%) of study participants read the current Ethiopian PrEP implementation guideline. The majority (97.5%) of participants heard about PrEP and the main source of information was from the health facility (Table 3).

The majority of the participants get information about PrEP from a health facility (Fig. 2).

Sexual behavior-related characteristics of healthcare workers

Seventy-two (18%) and 204 (51.4%) providers reported always or very often asking adult patients about their sexual activity. Two-thirds of providers reported always or very often offering HIV tests to sexually active adults who had not been previously tested for HIV, while the remaining one-third reported sometimes, rarely, or never doing so. About 276 (69.5%) of providers were reported always or very often offering HIV tests to adults seeking treatment for another sexually transmitted infection (STI). Twelve respondents (3%) reported never offering to test such patients. Just over 267 (68%) of providers always or very often refer high-risk patients to an HIV (or infectious disease) specialist after a positive test result. Generally, study participants have good sexual behavior in linking their patients to HIV testing but they have a limitation on prescribed PrEP (Fig. 3).

Knowledge of healthcare providers

Out of the 397 study participants, 221 (55.7%) with 95% CI (50.6–60.2) of the respondents had good knowledge, and 176 (44.3%) with 95% CI (39.8–49.4) had poor knowledge. Just below 1/3 of the providers 117 (29.47%) reported having trained in Ethiopian PrEP clinical practice guidelines, and around 221 (55.7%) of providers correctly answered 8 and above out of 11 knowledge-related questions. Of a total of 241 participants who read the guideline only 58.5% had good knowledge; also HCPs who serve greater than 20 patients per day were knowledgeable (59.4%) (Table 4).

Of the respondents, 82.6 percent were aware that HIV testing is important before starting PrEP and 74.75% of participants answered that commercial sex workers and serodiscordant negative couples are eligible for PrEP service. Concerning the number of drugs used for PrEP 61% of the respondents are familiar with two drugs used, but most of the health care providers lack the knowledge to differentiate which drugs and the effectiveness of the regime, 36.2% answered Tenofovir/lamivudine (TDF/3TC and (48.4%)) answered that PrEP is effectively greater than 90%. Most study participants lack knowledge related to the adverse effect, and the exclusion criteria of PrEP drugs were mostly answered below 50.0%%, which are 39.55%, 40.3%, and 48.4% respectively.

Factors affecting the knowledge of healthcare providers

Logistic regression analyses were performed to identify factors significantly associated with good HIV-PrEP knowledge. Those variables' p values less than 0.25 (age, sex, profession, educational level, working place, working area, worked in PEP, service year, training, reading the guideline, number of patients served, attitudes, and risky sexual behavior and HIV testing practice) were entered into multivariable logistic regression. Regarding a positive knowledge of HIV-PrEP, bivariable logistic regression showed several factors were significantly associated with this parameter. Being a male, serving more than 10 years, providers having favorable attitudes and good sexual behavior activity to HIV testing were the independent factors associated with a positive knowledge of HIV-PrEP in multi-variable logistic regression analysis.

The odds of having good knowledge were 2.5 times higher among healthcare providers who have more than 10 years of experience than HCPs having less than 5 years of experience [AOR] 2.52, 95% confidence interval [CI] (1.23–5.17) P-value: 0.012. The odds of healthcare providers’ knowledge among males were 1.7 times more likely to be knowledgeable than female healthcare providers (AOR 1.67, 95% CI ( 1.01–2.55) P-value: 0.017.

The knowledge of healthcare providers was also highly associated with the attitudes of study participants, the odds of having good PrEP knowledge were nearly 2 times higher among those who had favorable attitudes as compared to healthcare providers who had unfavorable attitudes about PrEP (AOR 1.92, 95% CI (1.25–2.95) P-value:0.003.

The other significantly associated independent variable with knowledge of PrEP during multiple logistic regressions was the sexual behavior of health care providers, the odds of having good knowledge of PrEP were 1.8 times higher among providers who had good sexual behavior and HIV testing practice as compared to HCPs who had poor sexual behavior and HIV testing practice (AOR 1.85, 95% CI (1.21–2.82) P-value: 0.004 (Table 5).

Attitudes of healthcare providers toward PrEP

The mean score of the total attitudes questions was 43 with SD ± 6.58. Out of the total of 397 study participants, 239 (60.2%) with 95% CI (55.0–65.0) of the respondents had a favorable attitudes, and 158 (39.8%) with a 95% CI (34.9–44.8) had an unfavorable attitudes.

Of the respondents, 322 (81.1%) agree and strongly agree that 3TC/TDF is a safe drug to use as PrEP. One hundred forty-nine (48.6%) of participants agreed that PrEP is an effective prevention tool in the real world. In addition, 249 (62.7%) of the participants also believe that PrEP is more effective than PEP. Fifty-five percent of participants also believe that PrEP will put their patients under discrimination, 250 (63%) also agreed and strongly agreed that PrEP leads to an increase in sexually transmitted diseases (Table 6).

Factors affecting attitudes of health care providers toward PrEP

Logistic regression analyses were performed to identify factors significantly associated with favorable attitudes toward HIV-PrEP. There were 12 factors (age, marital status, profession, educational level, working area, worked in PEP, service year, training, reading the guideline, heard about PrEP, knowledge, and providers' risky sexual behavior) found to be significantly associated with a favorable attitude of health care providers towards HIV-PrEP in bivariable analysis, but only the following 4 factors (training, reading the guideline, good knowledge, and profession) were identified as independent factors of attitudes of health care providers towards HIV-PrEP in multivariable analysis.

The odds of having favorable attitudes among nurses were 2.7 times more favorable than medical doctors (AOR 2.70, 95% CI (1.19–6.14) P-value: 0.018. The odds of having favorable attitudes among those who take basic PrEP training had 2 times more likely favorable attitudes than healthcare providers who didn’t train in the basic PrEP guidelines. (AOR 2.15, 95% CI (1.23–3.76) P-value: 0.008.

The favorable attitudes of healthcare providers were also highly associated with reading the PrEP guideline, the odds of having favorable PrEP attitudes among those who read the guideline were nearly two times higher than healthcare providers who didn’t read about PrEP guideline (AOR 1.66, 95% CI (1.02–2.70) P-value: 0.041.

The favorable attitudes of healthcare providers were also highly associated with the good knowledge of study participants. The odds of having a favorable attitude were two times higher among those who had good knowledge as compared to healthcare providers who had unfavorable attitudes about PrEP. (AOR 1.78, 95% CI (1.16–2.75) P-value: 0.009 (Table 7).

Discussion

In this study, the majority of participants 369 (92.9%) with 95% CI (90–95.3) heard about PrEP for HIV which is higher as compared to previous studies like research conducted in Deland Florida (75%), and in Rwanda, 86.4% of respondents heard about HIV PrEP39,40. This might be due to the difference in the period of adoption of the program and training opportunities.

In this study, the good knowledge of health care providers about HIV PrEP was 55.7% (50.6–60.2%), which was similar to the study conducted in America among Air Force health care providers (55%)36, Australia (51%) and in International AIDS Society-USA (IAS-USA) (51%)28. However, it is lower than the study done in the United Kingdom (80%)20, Tennessee Medical Center in America (78.75%)8, Italy (64.5%)23, and study in Florida 79%39. The possible explanation for this difference could be the tool (self-rated questionnaire) they used to rate the knowledge, countries that haven’t specific policies related to PrEP, and the other explanation could be study participants in the UK and America had an experience of being included in the previous study8.

On the other hand, health care providers who had good knowledge (55.7%) are higher than the study conducted in Boston Medical School (44%)26 and Rwanda < 50%40. This variation might be due to the study period, data collection method (they use a convenient sampling technique), late introduction of PrEP service, and then conducted in a small (51) study participants.

This study also found that healthcare providers who had work experience greater than or equal to 10 years had a significant association with a good knowledge of PrEP. HCPs who had this much experience were 2.5 times more likely to be knowledgeable than those who had less than 10 years of work experience (AOR 2.52). This study result is similar to the study conducted in New England26 and the USA Air Force36. The possible explanation could be health care providers who have more experience have a chance to participate in training and workshops related to HIV prevention strategies like PrEP, so greater engagement with certain continuing education tools and training influences PrEP knowledge. The other explanation might be young sexually active patients interested in PrEP may be more likely to seek out highly experienced HCPs41,42.

The other finding of this study was the significant association between the knowledge of PrEP and the sex of participants (males were approximately two times more likely knowledgeable than female healthcare providers (AOR 1.67). This study is in line with the study conducted in the UK and USA, which stated that there was a statistically significant difference in the proportion of male and female respondents who rated their knowledge of PrEP as high or medium.20,35,36.

The knowledge of healthcare providers was also highly associated with the attitudes of study participants. Those providers who had favorable attitudes to PrEP had a great association with a good knowledge of PrEP (AOR 1.92). This result is in line with the study conducted in Mexico and Brazil43 as well as in Florida39. The reason could be those healthcare providers who have a favorable attitude are eager to welcome the program and read the studies related to PrEP. The other reason might be providers who have favorable attitudes may read literature related to the efficacy and side effects of PrEP medication to increase the adherence of their patients44.

HCPs who had good sexual behavior were 2 times more likely to have a favorable attitude than those who had poor sexual behavior (AOR 1.85). This study is in line with a study conducted in Thailand and America38,45. The study found that discussing sexual risk history with patients, frequency of taking a sexual history, ever prescribing antiretroviral for HIV prevention, and offering patients HIV testing and linking to STI clinics for high-risk patients were significantly associated with independent variables with knowledge of PrEP46. The possible explanation could be those providers read different literature about HIV prevention strategies to cascade their daily activities or to answer questions raised by their patients21. The other reason could be those practicing sexual behavior activities had training on HIV prevention methods.

The other finding in this study was that 49% (45.6–55.7%) of healthcare providers discussed PrEP with high-risk patients, which is in line with the study in Florida (50%)39, greater than the study conducted in the US navy (29.9%)46. But it is lower than the study conducted in Italy (69%)23. This difference might be providers’ perception that patients do have high-risk behaviors and most patients have a low risk for infection and it may include a lack of training regarding PrEP, such as how to offer PrEP47. Another possible explanation is response bias, for example, providers know that they should be discussing and prescribing PrEP to high-risk patients according to practice guidelines, so they indicated that they were willing to do so when additional factors impact compliance in practice23.

The other pertinent finding of this study was the attitudes of health care providers about HIV PrEP was 60.2% (55.0–65.0%), which was similar to the study conducted in Tanzania (61%)24, and the multicenter study in Uganda, Botswana, and South Africa, which is less than 60%10. However, this finding is less than the study conducted in America (pooled prevalence of provider attitudes was 68%)48 and Italy (79%)23 The possible explanation for this difference could be the tool (self-rated questionnaire) they used to rate the attitudes. The other explanation could be the time of adoption of the program, those countries have accepted the PrEP program since 20159, so providers had a chance to get training and symposiums related to HIV prevention. However, the current study was conducted after 3 years of implementation in Ethiopia.

Similarly, these studies are also lower than the study done in Belgium (78.4%)49, South Africa (79%), and sub-Saharan African countries (66%)10,44. The possible explanation for this difference was that to study participants this study believed that promoting HIV testing and treating HIV-infected patients is more important than offering PrEP. On the other finding, this result was much greater than the study conducted in Rwanda, which is 40%. This discrepancy related to study participants in that study believed that PrEP leads patients to highly risky sexual behavior (59.3%) and is related to an increase in sexually transmitted diseases (58.3%)40.

The finding of this study showed that significant association between the attitudes of HCPs and the formal training of PrEP (trained HCPs were 2 times more likely favorable attitudes than untrained health care providers (AOR 2.15). This study is in line with the study conducted in Kenya42, Tanzania24, Nigeria41, and South Africa44. The possible explanation for this association is that formal training is the key to recording accurate and reliable data (efficacy; adherence, the side effect of PrEP) and it increases the attitudes of HCPs28.

The favorable attitudes of health care providers were also highly associated with reading the PrEP guideline, Study participants who read the guideline were approximately two times more likely to have a favorable attitude about HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis as compared to health care providers who didn’t read about PrEP guideline (AOR 1.66). This finding is in line with the study conducted at Tennessee Medical Center8, Florida39, Germany22, and Kenya25. The possible reason might be those who read the guideline get a clear picture of PrEP and more detailed information about it, so HCPs who read the guideline might have a favorable attitude9.

The main concerns about PrEP found in our study were adherence to PrEP and long-term side effects, and it increases risky sexual behavior, which has also been found in other studies in Belgium. As found in other studies, addressing the belief that PrEP is an effective intervention to prevent HIV4,37 and that it is a good prevention strategy may be crucial to enhancing the acceptance of PrEP among HCPs.

The favorable attitudes of healthcare providers were also highly associated with the knowledge of PrEP, knowledgeable participants had a favorable attitude about HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis as compared to healthcare providers who did not know about PrEP (AOR 1.78). This finding is in line with the study conducted at Tennessee Medical Center8, Germany22, and Kenya25. This finding may be explained by that less knowledgeable physicians possibly had more HIV-PrEP concerning issues about medication adherence behavior and risk of developing HIV drug resistance in real-life clinical practice38.

A finding that was associated with a favorable attitude towards PrEP was profession (nurses were more likely to have a favorable attitude by three times as compared to medical doctors (AOR 2.7). This study is in line with the study conducted in Washington20, and Thailand36, which found that nurses (73%) have a higher attitude toward HIV PrEP than physicians. This discrepancy may be due to the preview paradox (physicians believing that PrEP services must be given by other HCPs like nurses and clinical officers) and this paradox leads them to an unfavorable attitude15.

Conclusion and recommendations

In general, the finding of this study shows that the knowledge and attitudes of healthcare providers who were working in East Gojjam zone facilities were low, even more than half of healthcare providers in the East Gojjam zone had good knowledge and a favorable attitude. This study showed that sex (men), service years greater than 10 years, attitudes, and sexual behavior were found to be significantly associated with the PrEP knowledge of healthcare providers. Profession (being a nurse), training, reading the guidelines, and good sexual behavior were significantly associated with the favorable attitudes of healthcare providers towards HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Highly experienced HCPs should share their experience with those who have less experience. Training to female HCPs and clinicians with limited work experience should undergo PrEP-specific training to increase and promote the use of PrEP among high-risk groups and reduce the risk of HIV infections. Health facilities should make available PrEP guidelines within their workplace and standardize written PrEP. The study focuses on the knowledge and attitudes of HCPs in geographically limited areas so, we recommend that future researchers study nationwide by including the practice.

Limitations of the study

The study may be subjected to the response set bias from the respondents. In addition to the above limitation, the sexual behavior component may have been influenced by social desirability bias.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AGYW:

-

Adolescent girls and young women

- AIDS:

-

Acquired immune compromised syndrome

- CVI:

-

Content validity index

- FMOH:

-

Federal Ministry of Health

- HCPS:

-

Health care providers

- I-CVI:

-

Item content validity index

- PLWA:

-

People living with AIDS

- PrEP:

-

Pre Exposure prophylaxis

- SHAs:

-

Sexual health advisors

- TDF/3TC:

-

Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate + Lamuvidine

- UNAIDS:

-

United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS

References

Colvin, C. J. HIV/AIDS, chronic diseases and globalisation. Glob. Health 7(1), 1–6 (2011).

Carter, M. R., Aaron, E., Nassau, T. & Brady, K. A. Knowledge, attitudes, and PrEP prescribing practices of health care providers in Philadelphia, PA. J. Prim. Community Health 10, 2150132719878526 (2019).

Moore, E. et al. Tennessee healthcare provider practices, attitudes, and knowledge around HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. J. Prim. Community Health 11, 2150132720984416 (2020).

Federal, H. HIV Prevention in Ethiopia National Road Map 2018–2020 (Federal HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control Office Addis Ababa, 2018).

Carter, M. R., Aaron, E., Nassau, T. & Brady, K. A. Knowledge, attitudes, and PrEP prescribing practices of health care providers in Philadelphia, PA. J. Prim. Care Community Health 10, 2150132719878526 (2019).

Zhang, C. et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation cascade among health care professionals in the United States: Implications from a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDS 33(12), 507–527 (2019).

Ajayi, A. I. et al. Low awareness and use of pre-exposure prophylaxis among adolescents and young adults in high HIV and sexual violence prevalence settings. Medicine 98(43), e17716 (2019).

Moore, E. et al. Tennessee healthcare provider practices, attitudes, and knowledge around HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. J. Prim. Care Community Health 11, 2150132720984416 (2020).

Karim, S. S. A. & Baxter, C. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation in Africa: Some early lessons. Lancet Glob. Health 9(12), e1634–e1635 (2021).

Lanham, M. et al. Health care providers’ attitudes toward and experiences delivering oral PrEP to adolescent girls and young women in Kenya, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. BMC Health Serv. Res. 21(1), 1–12 (2021).

Bekker, L. G. et al. Southern African guidelines on the safe use of pre-exposure prophylaxis in persons at risk of acquiring HIV-1 infection. South. Afr. J. HIV Med. 17(1), 455 (2016).

Baeten, J. et al. Near elimination of HIV transmission in a demonstration project of PrEP and ART. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) (2015).

Organization WH. WHO Implementation Tool for Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) of HIV Infection: Module 5: Monitoring and Evaluation (World Health Organization, 2018).

Ross, I. et al. Awareness and attitudes of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among physicians in Guatemala: Implications for country-wide implementation. PLoS ONE 12(3), e0173057 (2017).

Pleuhs, B., Quinn, K. G., Walsh, J. L., Petroll, A. E. & John, S. A. Health care provider barriers to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in the United States: A systematic review. AIDS Patient Care STDs 34(3), 111–123 (2020).

Coalition, AVA. Global PrEP Tracker https://www.prepwatch.org/resource/global-prep-tracker. Accessed; 2022.

Country, E. & Plan, R. O. Strategic Direction Summary 2021 (2021).

Desai, M., Field, N., Grant, R. & McCormack, S. J. B. Recent Advances in Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for HIV 359 (2017).

Maude, R., Volpe, G. & Stone D. Knowledge, attitudes and practice of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) against HIV infection of medical providers at an academic center. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 4(Suppl 1), S437 (2017).

Desai, M., Gafos, M., Dolling, D., McCormack, S. & Nardone, A. Healthcare providers’ knowledge of, attitudes to and practice of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection. HIV Med. 17(2), 133–142 (2016).

Lane, W., Heal, C. & Banks, J. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: Knowledge and attitudes among general practitioners. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 48(10), 722–727 (2019).

Kutscha, F., Gaskins, M., Sammons, M., Nast, A. & Werner, R. N. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) counseling in Germany: Knowledge, attitudes and practice in non-governmental and in public HIV and STI testing and counseling centers. Front. Public Health 8, 298 (2020).

Puro, V., Palummieri, A., De Carli, G., Piselli, P. & Ippolito, G. Attitudes towards antiretroviral Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) prescription among HIV specialists. BMC Infect. Dis. 13, 217 (2013).

Pilgrim, N. et al. Provider perspectives on PrEP for adolescent girls and young women in Tanzania: The role of provider biases and quality of care. PLoS ONE 13(4), e0196280 (2018).

Mireku, M. et al. Health care providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards provision of PrEP to adolescent girls and young women in Kenya. HIV Research for Prevention Conference (2018).

Krakower, D. S. et al. Knowledge, beliefs and practices regarding antiretroviral medications for HIV prevention: Results from a survey of healthcare providers in New England. PloS ONE 10(7), e0132398 (2015).

Organization WH. Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Prevention, Testing, Treatment, Service Delivery and Monitoring: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach (World Health Organization, 2021).

Blumenthal, J. et al. Knowledge is Power! Increased provider knowledge scores regarding pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) are associated with higher rates of PrEP prescription and future intent to prescribe PrEP. AIDS Behav. 19(5), 802–810 (2015).

Goparaju, L. et al. Stigma, partners, providers and costs: Potential barriers to PrEP uptake among US women. J. AIDS Clin. Res. 8(9), 730 (2017).

Marcus, J. L. et al. Barriers to preexposure prophylaxis use among individuals with recently acquired HIV infection in Northern California. AIDS Care 31(5), 536–544 (2019).

Mayer KH, Agwu A, Malebranche D (2007) Barriers to the wider use of pre-exposure prophylaxis in the United States: A narrative review. Adv. Ther. 37(5), 1778–1811.

Ethiopian Public Health Institute E, Federal Ministry of Health F, Icf. Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019 (EPHI/FMoH/ICF, 2021).

Aynalem, B. Y. & Melesse, M. F. Health extension service utilization and associated factors in East Gojjam zone, Northwest Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 16(8), e0256418 (2021).

Authority CS. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (2019).

Wood, B. R. et al. Knowledge, practices, and barriers to HIV preexposure prophylaxis prescribing among Washington state medical providers. Sex. Transm. Dis. 45(7), 452–458 (2018).

Hakre, S. et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among US Air Force Health Care Providers. Medicine 95(32), e4511 (2016).

MOH. FDRE Implementation Tool for Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) of HIV Infection: Monitoring and Evaluation (MOH, 2019).

Wisutep, P. et al. Attitudes towards, knowledge about, and confidence to prescribe antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis among healthcare providers in Thailand. Medicine 100(49), e28120 (2021).

Gunn, L. H. et al. Healthcare providers’ knowledge, readiness, prescribing behaviors, and perceived barriers regarding routine HIV testing and pre-exposure prophylaxis in DeLand, Florida. SAGE Open Med. 7, 2050312119836030 (2019).

Kambutse, I., Igiraneza, G. & Ogbuagu, O. Perceptions of HIV transmission and pre-exposure prophylaxis among health care workers and community members in Rwanda. PLoS ONE 13(11), e0207650 (2018).

Abayomi, J. A., Adefunke, A., Olugbemiga, P., Oluwalusi, E. & Omolola, O. Knowledge, attitudes and practice of healthcare workers towards availability of antiretroviral pre-exposure prohylaxis in Nigeria. J. Clin. Res. HIV AIDS Prev. 3(3), 46–59 (2018).

Irungu, E. M. et al. Training health care providers to provide PrEP for HIV serodiscordant couples attending public health facilities in Kenya. Glob. Public Health 14(10), 1524–1534 (2019).

Vega-Ramirez, H. et al. Awareness, knowledge, and attitudes related to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and other prevention strategies among physicians from Brazil and Mexico: A cross-sectional web-based survey. BMC Health Serv. Res. 22(1), 532 (2022).

Joseph Davey, D. L. et al. Healthcare provider knowledge and attitudes about pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in pregnancy in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Care 32(10), 1290–1294 (2020).

Walsh, J. L. & Petroll, A. E. Factors related to pre-exposure prophylaxis prescription by U.S. primary care physicians. Am. J. Prev. Med. 52(6), e165–e172 (2017).

Wilson, K. et al. Provider knowledge gaps in HIV PrEP affect practice patterns in the US Navy. Mil. Med. 185(1–2), e117–e124 (2020).

Castel, A. D. et al. Understanding HIV care provider attitudes regarding intentions to prescribe PrEP. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 70(5), 520–528 (2015).

Krakower, D. S. & Mayer, K. H. The role of healthcare providers in the roll out of preexposure prophylaxis. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 11(1), 41–48 (2016).

Reyniers, T. et al. Physicians’ preparedness for pre-exposure prophylaxis: Results of an online survey in Belgium. Sex. Health 15(6), 606–611 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Shebel Berenta Hospital for funding to do this research. Our acknowledgment also extends to Debre Markos University staff for their support. We would like to acknowledge data collectors and study participants for providing valuable information and for the success of this research.

Funding

Shebel Berenta Hospital in collaboration with Debre Markos University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.M. writing original draft preparation: G.M., A.D., T.L., A.A. Methodology, Formal analysis G.M., A.D., T.L., A.A. All authors reviewed, read, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mekonnen, G., Liknaw, T., Anley, A. et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and associated factors towards HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among health care providers. Sci Rep 14, 6168 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56371-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56371-0

Keywords

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.