Abstract

To identify pregnant women’s attitudes towards, and acceptance and rejection of, COVID-19 vaccination. This prospective, descriptive, implementation study was conducted in the Antenatal clinic of Siriraj Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand. In Phase I, 40 pregnant women were interviewed. Phase II consisted of questionnaire development and data validation. In Phase III, the questionnaire was administered to 400 participants. Pregnant women’s attitudes towards and acceptance and rejection of COVID-19 vaccination. Most pregnant women were uncertain about the potential harm of vaccination to themselves or their unborn child, including risks such as miscarriage or premature birth (59–66/101 [58.4%–65.3%]; OR 2.53–8.33; 95% CI 1.23–3.60, 5.17–19.30; P < 0.001) compared to those who disagreed with vaccination. Their vaccination decisions were significantly influenced by social media information regarding vaccination complications in pregnant women (74/101 [73.3%]; OR 15.95; 95% CI 2.15–118.55; P = 0.001) compared to those who disagreed with vaccination. Most pregnant women opined that they should not receive a COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 6.57; 95% CI 2.44–17.70; P = 0.001). Most also rejected vaccination despite being aware of its benefits (AOR 17.14; 95% CI 6.89–42.62; P < 0.001). Social media messages and obligatory vaccination certifications influence maternal vaccination decisions. Pregnant women believe vaccination helps prevent COVID-19 infection and reduces its severity. Nevertheless, the primary reason for their refusal was concern about potential harm to their unborn child or themselves during pregnancy.

The Thai clinical trials registry: TCTR20211126006.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a novel infectious disease that was first reported in Wuhan, China, on 31 December 2019. The symptoms were ranging from the common cold to more severe illnesses. The new virus was named ‘SARS-CoV-2’, and COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic in March 20201.

Pregnant women face an elevated risk of severe infections and are more prone to experiencing serious complications from COVID-19 compared to non-pregnant women. These complications may involve ICU admission, invasive ventilation, ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation), and even death2,3,4 Physiological changes in the immune system and circulatory blood flow during pregnancy make pregnant women susceptible to respiratory infection from SARS-CoV-25 Serious COVID-19 infection during pregnancy can result in disabilities and abnormalities of the foetus, intrauterine foetal death, and neonatal death during the postpartum period6.

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that pregnant women are one of the groups at high risk of developing severe symptoms when they are infected with COVID-19. Women infected with COVID-19 are more likely to get sick from the infection than non-pregnant people. They may need to be admitted to an intensive care unit or use a ventilator or special breathing device. Severe illness from COVID-19 during pregnancy can lead to death. There is also a risk of complications affecting the pregnancy and the unborn child, such as miscarriage or death. Pregnant women infected with coronavirus are at increased risk of preeclampsia, miscarriage and other complications from pregnancy7. Respiratory complications may also prolong their hospital stay. Pregnant women with severe illnesses from coronavirus infection may also die. Therefore, raising awareness of the potential hazards of COVID-19 infection during pregnancy and counselling pregnant women about the safety of COVID-19 vaccines is critical8.

Risk factors for severe COVID-19 during pregnancy or postpartum include medical complications, age over 25, living/working in high COVID-19 areas, and close proximity to potentially infected individuals9. Pandemic restrictions limited prenatal care, leading to increased stillbirths and preterm births10,11,12. The WHO in the Western Pacific region advocates for vaccination and other measures to control COVID-19, with many countries endorsing at least one vaccine since 202213.

The United States CDC currently monitors COVID-19 vaccinations during pregnancy and maternal and foetal complications during the first trimester to better understand the impact of vaccination on pregnancy and unborn children. Recent data show that administering an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy reduces the risk of serious illness from COVID-19 infection14,15,16. Vaccinations during pregnancy have also been found to produce antibodies that can help protect babies from COVID-19 because antibodies have been found in babies’ umbilical cord blood17,18,19. A recent small study found that 57% of babies at 6 months born to mothers vaccinated during pregnancy had antibodies to COVID-19. This proportion was substantially higher than that for babies born to mothers with a COVID-19 infection during pregnancy: only 8% of these babies had antibodies to COVID-1920.

Fell and colleagues reported that neonates born to vaccinated mothers did not have an increased need for admission to a neonatal intensive care unit and had better APGAR scores than neonates born to unvaccinated mothers21. In addition, vaccination was not associated with an increased risk of postpartum haemorrhage or chorioamnionitis. Pregnant women are a high-risk group recommended for vaccination to avoid complications from the disease, hospitalisation, intensive care unit admission and death21. Worldwide evidence shows that COVID-19 vaccinations during pregnancy are not associated with maternal or neonatal adverse outcomes and are effective in preventing infection in mothers and neonates during the first few months of life.

Numerous medical organisations recommend COVID-19 vaccination of pregnant women throughout their pregnancy21. Among them are the United States CDC, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine, and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine.

WHO also works with affiliated governments through the multi-channel COVAX (Covid-19 Vaccines Global Access Facility) to facilitate access to vaccines and the earliest possible distribution of primary vaccinations. WHO recommended that the highest priority be given to distributing initial vaccination stocks to high-risk groups within each country. These were physicians, nurses, health workers, the elderly and people with significant health compromises. COVID-19 vaccines have become widely available since 202210. This means that the provision of vaccinations can be expanded to other important groups, such as pregnant women, and the general population10,22.

However, many pregnant women have decided not to get vaccinated against COVID-19. They adopted this stance despite the publication of reports confirming the safety of vaccinating pregnant women in all trimesters of pregnancy17,23. We wanted in-depth information on pregnant women’s attitudes towards vaccination against COVID-19 infection and their reasons for accepting or refusing vaccination. The information gathered would facilitate planning for the care of pregnant women in the scenario of a new wave of outbreaks.

Materials and methods

This was a prospective, descriptive study. The Siriraj Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine at Siriraj Hospital approved the protocol (Si1018/2021). The Thai Clinical Trials registration number is TCTR20211126006.

This survey study utilised validated questionnaires (Phase III). The sample size was calculated using a proportion of the results of interest of 50% (P = 0.5), an estimation error of ≤ 5% and a 95% confidence level (type I error = 0.05; 2-sided). The number of pregnant women who needed to be surveyed was ≥ 385.

The research was divided into 3 consecutive phases: (1) in-depth interview; (2) questionnaire development and validation; (3) questionnaire administration (Supplementary Information).

Phase I: in-depth interviews

To find participants for Phases I and III, pregnant women of any gestational age attending the hospital’s antenatal ward without any restriction were invited to a private counselling room where the research project was described. The pregnant women participating in the study were Thai women aged at least 16 years and literate. The women were given time to ask questions and consider whether they wished to enrol in the trial. They were advised that they could decline to participate or withdraw at any stage and for any reason if they did enrol. All women who volunteered to be research subjects for Phases I and III were asked to sign an informed consent form.

This phase collected information about the following 4 areas:

-

1.

General pregnant women information

-

2.

Pregnant women attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination, knowledge of complications of COVID-19 infection during pregnancy, and reasons for accepting or rejecting COVID-19 vaccination

-

3.

Decision-making about COVID-19 vaccination

-

4.

Frustrations with deciding whether to be vaccinated

We conducted in-depth interviews with pregnant women to explore their knowledge, attitudes, acceptance, and refusal of vaccination. The insights gathered from these interviews were then utilized to develop a questionnaire.

Between 1st May and 15nd June 2022, in-depth interviews for Phase I were conducted with 40 women. Before these interviews commenced, the participants were asked for permission for the conversations and their structured interview to be audio-recorded. Forty-five pregnant women were invited to participate in the in-depth interview phase. Five pregnant women declined the interview because they were uncomfortable while answering the question and being audio-recorded. The subjects initially completed an attitude assessment questionnaire. It dealt with their attitudes, knowledge of the complications of a COVID-19 infection during pregnancy, and their reasons for accepting or rejecting COVID-19 vaccination. Several other aspects were then investigated in a structured interview. One aspect related to their decision-making for COVID-19 vaccination and any frustration they felt before deciding to be vaccinated.

The total time from the commencement of the questionnaire until the completion of the comprehensive interview was approximately 30 min. The data integrity of the research questions was later verified. The completeness of data provided by patients in the basic demographic questions regarding their history of vaccination, type of vaccination, and acceptance or rejection was reexamined to ensure data integrity.

Phase II: questionnaire development and validation

Between 16th June and 31st July 2022, the data from the provisional questionnaire (non-revised and non-validated questionnaire) and the in-depth interviews administered during Phase I were analysed to determine the means and standard deviations. Doing so enabled the questionnaire and the interview questions to be refined. The validity and reliability of the revised questionnaire and interview questions were tested before their use in the next phase. The revised questionnaire and interview questions underwent testing for validity and reliability before their implementation in the subsequent phase. A specialized statistician assessed the questionnaire's validity, focusing on double-barreled, confusing, and leading questions. To evaluate the test–retest reliability, the same respondents completed the questionnaire again one month after the initial completion. Forty pregnant women were given a revised questionnaire to test its validity and accuracy.

Phase III: questionnaire administration (final phase)

Between 1st August and 31st October 2022, the validated questionnaires which has been tested for validity and accuracy, were given to 430 pregnant women (different group from Phase I) in the hospital’s antenatal ward during the final phase. Out of 430 pregnant women approached for the study, 30 declined to participate, resulting in a total recruitment of 400 women in this specific timeframe. There was no dropout of pregnant women during response to questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise demographic data. Categorical data are presented as numbers and percentages. Continuous data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median and range. All analyses were performed using PASW Statistics for Windows (version 18.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Multivariate analysis was performed using the forward stepwise and multiple logistic regression methods.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis were used to identify statistically significant independent factors association. Factors having a p-value of less than 0.10 in the univariate analysis were imported to multivariate logistic regression to control the effect of possible confounding factors. Factors were chosen using the forward-stepwise likelihood ratio approach in the multiple logistic regression model, and the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with its 95% CI at a p-value of ≤ 0.05 was used to determine statistically significant association.

Institutional review board statement

The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Siriraj Institutional Review Board (COA [Si1018/2021]). All procedures performed in studies are not involving human participants.

Informed consent statement

Written, informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

The majority received a COVID-19 vaccination before pregnancy (341 cases [85.3%]), with approximately half receiving 2 vaccine doses (189 cases [47.3%]; Table 1). A fifth of the respondents (91 cases [22.8%]) had contracted COVID-19 before their pregnancy (Table 1).

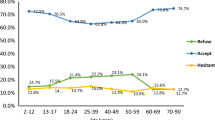

More than 50% of the respondents agreed that COVID-19 is a potentially dangerous disease and can cause miscarriages and premature births. However, over 50% were unsure whether the vaccine could protect against COVID-19, might harm an unborn baby, or could increase the risk of miscarriage or preterm birth (Fig. 1). More than half (55.8%) were confident that the COVID-19 vaccine could reduce the severity of the disease.

Of those who accepted the COVID-19 vaccination, more than 50% believed that the vaccine would protect against COVID-19, 65.6% were unsure whether the vaccine would harm their child, and 59.2% were still unsure and needed to consult others before getting vaccinated. Of those who refused to be vaccinated against COVID-19, more than 50% were unsure if the vaccine could cause foetal abnormalities or increase the risk of miscarriage or preterm birth (Fig. 2).

More than 70% of the pregnant women indicated that the core information that influenced their vaccination decisions was the following:

-

1.

the severity of COVID-19 illness

-

2.

the reduction in infection and disease severity resulting from vaccination

-

3.

the potential harm to an unborn baby caused by COVID-19 vaccines

-

4.

the level of immunity to COVID-19 in women who have been previously vaccinated (Table 2)

More than 50% of the women reported that obligatory vaccination certifications impacted their daily work and their decisions to be vaccinated. Furthermore, over 50% indicated that social media information about the dangers of vaccination or the death of pregnant women influenced their vaccination decisions. Additionally, more than 60% of the women agreed that the type, number of vaccinations, and levels of immunity to COVID-19 affected their vaccination decisions (Table 3).

Of the 101 pregnant women who rejected having a COVID-19 vaccination, most were unsure whether the vaccine could harm themselves (59/101 [58.4%]; odds ratio [OR] 8.26; 95% CI 3.59–19.01; P < 0.001) or their unborn child (66/101 [65.3%]; OR 5.26; 95% CI 1.85–14.98; P < 0.001), including miscarriage (61/101 [60.4%]; OR 8.33; 95% CI 3.60–19.30; P < 0.001) or premature birth (66/101 [65.3%]; OR 2.53; 95% CI 1.23–5.17; P < 0.001; Table 4). They believed that too many vaccinations might harm themselves (43/101 [42.6%]; OR 3.04; 95% CI 1.10–8.38; P = 0.018) or their unborn child (48/101 [47.5%]; OR 4.26; 95% CI 1.22–14.81; P = 0.006; Table 4).

Most pregnant women believed they should not be vaccinated against COVID-19 during pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 6.57; 95% CI 2.44–17.70; P = 0.001; Table 5). They opined that COVID-19 vaccines increase the risk of premature birth (AOR 5.57; 95% CI 1.69–18.37; P = 0.011). Most rejected vaccination despite knowing its benefits (AOR 17.14; 95% CI 6.89–42.62; P < 0.001; Table 5).

Discussion

We engaged in in-depth interviews with pregnant women to delve into their knowledge, attitudes, acceptance, and refusal of vaccination. The valuable insights obtained from these interviews were instrumental in shaping the authentic data used to construct a questionnaire.

In our study, 85.3% of the pregnant women were vaccinated before becoming pregnant and understood the potential severity of COVID-19. Nevertheless, once pregnant, 50% of this subgroup had no confidence in the vaccination. They were concerned about the dangers of the vaccine to themselves and their unborn children, especially miscarriage and premature birth. This concern was evident despite their being aware that the vaccine can reduce the severity of the disease.

Our research also found that the pregnant women’s level of immunity to COVID-19 did not affect their vaccination decisions. The effectiveness of vaccines varies depending on the vaccine type and evolves over time within the pregnant population. The variations in immunity can be influenced by factors such as maternal age and underlying diseases, body mass index, and gestational age24. Nevertheless, pregnant women continue to express concerns about their immunity following previous injections and are hesitant to receive any further vaccinations during pregnancy.

Even if they knew their immunity level, they still decided not to get vaccinated because they were concerned about possible harm to the unborn baby, miscarriage or preterm delivery. This attitude must be adjusted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Several studies have shown that vaccination against COVID-19 before and during pregnancy is safe, effective and beneficial to both the mother and child. The benefits of getting a COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy far outweigh any potential adverse consequences23,25,26,27,28.

No COVID-19 vaccine contains a live virus, so the vaccines do not cause COVID-19 infection in recipients, including pregnant women and their foetuses23,25,26,27,28. However, our investigation found that most respondents were uncertain whether the vaccine was safe for themselves and their unborn children. The women were unsure whether the vaccine would help prevent infection in their unborn babies. Most also believed that multiple vaccinations would harm their unborn children. This lack of information made it very challenging for them to decide whether to be vaccinated while pregnant.

Regarding the safety of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines (Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech), no problems have been found for women vaccinated with them before or during pregnancy or for their unborn children23,25,26,27,28. Data from studies in the United States, Europe and Canada show that their use during pregnancy is not associated with an increased risk of complications, such as preterm birth, miscarriage and postpartum haemorrhage21,26,29. There is no increased risk of miscarriage in pregnant women administered an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine before or during early pregnancy (before 20 gestational weeks)25,26,28,29. A study from Chicago found that COVID-19 vaccination in pregnant women before and during the first trimester was not associated with a risk of congenital malformations30.

The administration of 2 primary doses of a COVID-19 mRNA vaccine to mothers during their pregnancy helped protect babies younger than 6 months from being hospitalised due to COVID-19 infection. In our investigation, the majority (84%) of infants hospitalised with an infection were born to women not vaccinated during pregnancy31.

Our research found that the type and number of vaccinations influenced vaccination decisions. In Thailand, the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines are more popular than the other COVID-19 vaccines available in the country, and these 2 vaccines have been reported to be safe in pregnant women23. However, some vaccination centres in Thailand only provide 1 type of vaccine. Consequently, people seeking vaccination may find that their preferred vaccine is unavailable. If an alternative vaccine can be provided by allowing pregnant women to select the vaccine themselves, it would likely increase the vaccination rate among pregnant women.

In addition, our research found that vaccination decisions are influenced by social media news about the dangers to mothers and unborn children, including death and disability. Most of the pregnant women in our study rejected vaccination because they were uncertain whether vaccination would increase their foetuses’ immunity. Recent research has revealed the role of social media in disseminating information and potentially influencing people’s attitudes towards vaccination. Studies have also shown the positive potential of social media in public health interventions and overcoming vaccination hesitancy among mothers32,33,34,35. Therefore, there should be thorough scrutiny of the various roles of social media in disseminating information to the public and influencing individual behaviour in the context of public health activities. This approach will give pregnant women a correct understanding of COVID-19 vaccines.

Vaccination certifications also play a key role in pregnant women’s vaccination decisions. Attending workplaces or meetings involving large groups of people puts individuals at risk of contracting COVID-19. Therefore, most public and private organisations require employees attending workplaces to be vaccinated to the levels recommended by the Thai Ministry of Health. Employers may also require certification of COVID-19 vaccination status. These restrictive policies pressurise pregnant women to get vaccinated even if they disagree with having a vaccination.

WHO has commented that COVID-19 is a health emergency that does not give governments many choices in quickly returning the situation to normal. Regarding calls for the widespread use of COVID-19 vaccination certificates, WHO recognises that introducing such certificates is risky and may result in harm. The general use of the certificates may cause deviations from their initial objectives: to ensure continuity of care and to provide proof of vaccination status. Legal or ethical considerations may be raised by further potential uses for vaccination certificates, for example, public health surveillance, pharmacovigilance, research, and exemptions to public health and social measures. WHO cites legal obligations to protect patient data and the need to respect human rights and fundamental freedoms. To this end, WHO has recommended that data protection measures be in place before adopting digital vaccination certificates. It has also stressed that vaccination certificates must not be considered a substitute for health surveillance36.

Our study presented both similar and different results from the previous study about attitudes, acceptance and rejection of COVID-19 vaccination among breastfeeding women34. Both pregnant and breastfeeding women believed that vaccines can reduce infection and disease severity. The women’s COVID-19 immunity levels did not affect their acceptance or rejection of vaccination and some mothers rejected vaccination because of concerns about possible harm to them or their newborns. The safety of COVID-19 vaccination to the unborn and newborn babies and mothers is the main concerning of both pregnant and breastfeeding women. However the different results of pregnant women from breastfeeding women were the effect of social media messages and vaccination certifications to their decision. Pregnant women had more concern about those issue than breastfeeding women. Most of pregnant women were still working and COVID-19 vaccination certifications were important to their works. While breastfeeding women have a right for stop working up to 90 days, therefore vaccination certification is not required.

To enhance COVID-19 vaccination rates during pregnancy, it is essential to address the significant decline in pregnant women's confidence in vaccination. Targeted strategies involve implementing comprehensive education and communication campaigns to dispel misinformation and underscore the safety and benefits of vaccination for both mothers and unborn children. Specific measures include developing focused educational initiatives, employing communication strategies to counter social media influence, improving information accessibility about vaccine types, establishing clear certification guidelines for safety, and tailoring messaging to address concerns about potential harm to unborn babies. These efforts aim to increase vaccination acceptance among pregnant women, contributing to improved maternal and fetal health outcomes.

Our study is affected by some limitation. The study design was prospective cross-sectional study which represented the real situation of COVID-19 outbreak during that time. The study is limited by the exclusive recruitment of the sample from Siriraj Hospital. Despite this, it's crucial to recognize that Siriraj Hospital, functioning as both a medical school and a referral center in Bangkok, draws patients from diverse regions of Thailand seeking advanced prenatal care. The selection of 400 pregnant women aimed to represent a varied demographic from different parts of the country. Although participants were not randomly chosen and were exclusively from Siriraj Hospital, the study intended to capture the extensive demographics and geographic diversity inherent in the hospital's patient population. Most of pregnant women (85.3%) had a history of COVID-19 vaccination which would affect the decision making for repeated vaccination. Their actual attitude may be affected by the severity of disease and availability of database of COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy at that time.

The strength of our study is the less of “socially desirable” bias. In phase I, participant was in-depth interviewed in a close area by only single interviewer and in phase III, pregnant women response questionnaire in a closed place. The respondent can present the actual attitude, acceptance or rejection of COVID-19 vaccination.

Conclusions

Although COVID-19 severity has decreased, it is essential to note that this factor does not significantly influence pregnant women's decisions to accept or refuse vaccination. The study findings indicate that pregnant women hold the belief that vaccines play a crucial role in preventing infection and mitigating the severity of the disease. Nevertheless, their main reason for refusing injections is concern about potential harm to their unborn children and themselves during pregnancy. Social media communications and obligatory vaccination certifications influence maternal vaccination decisions. Providing accurate information through social media will enable pregnant women to better understand the role of vaccination in reducing the severity of the disease and the complications for mothers and babies both during pregnancy and after childbirth.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors (Email address: saifon.cha@mahidol.ac.th) upon reasonable request and with permission of Faculty of Medicinle, Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University.

References

Wang, C., Horby, P. W., Hayden, F. G. & Gao, G. F. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet 395(10223), 470–473 (2020).

Jamieson, D. J. & Rasmussen, S. A. An update on COVID-19 and pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 226(2), 177–186 (2022).

Mullins, E. et al. Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes of COVID-19: coreporting of common outcomes from PAN-COVID and AAP-SONPM registries. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 57(4), 573–581 (2021).

Simbar, M., Nazarpour, S. & Sheidaei, A. Evaluation of pregnancy outcomes in mothers with COVID-19 infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 43(1), 2162867 (2023).

Wastnedge, E. A. N. et al. Pregnancy and COVID-19. Physiol. Rev. 101(1), 303–318 (2021).

Dashraath, P. et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 222(6), 521–531 (2020).

Wei, S. Q., Bilodeau-Bertrand, M., Liu, S. & Auger, N. The impact of COVID-19 on pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 193(16), E540–E548 (2021).

COVID-19 Vaccines While Pregnant or Breastfeeding. Centers for Disease control and prevention. Updated June 13, 2022. (National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), Division of Viral Diseases).

Pregnant and recently pregnant people: At Increased Risk for Severe Illness from COVID-19. (National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), Division of Viral Diseases, 2021) https://www.who.int/westernpacific/emergencies/covid-19/covid-19-vaccines (2022).

Burki, T. The indirect impact of COVID-19 on women. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20(8), 904–905 (2020).

Khalil, A. et al. Change in the incidence of stillbirth and preterm delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 324, 705–706 (2020).

Roberton, T. et al. Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: A modelling study. Lancet Glob. Health. 8(7), e901–e908 (2020).

Western Pacific regional road map for COVID-19 vaccination response 2021–2022 (WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific, 2022) https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/359078.

Dagan, N. et al. Effectiveness of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in pregnancy. Nat. Med. 27(10), 1693–1695 (2021).

Stock, S. J. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination rates in pregnant women in Scotland. Nat. Med. 28(3), 504–512 (2022).

Theiler, R. N. et al. Pregnancy and birth outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM. 3(6), 100467 (2021).

Gray, K. J. et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine response in pregnant and lactating women: a cohort study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 225(3), 303.e1-303.e17 (2021).

Nir, O. et al. Maternal-neonatal transfer of SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin G antibodies among parturient women treated with BNT162b2 messenger RNA vaccine during pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM. 4(1), 100492 (2022).

Yang, Y. J. et al. Association of gestational age at coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination, history of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, and a vaccine booster dose with maternal and umbilical cord antibody levels at delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 139(3), 373–380 (2022).

Shook, L. L. et al. Durability of anti-spike antibodies in infants after maternal COVID-19 vaccination or natural infection. JAMA. 327(11), 1087–1089 (2022).

Fell, D. B. et al. Association of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy with adverse peripartum outcomes. JAMA. 327(15), 1478–1487 (2022).

Ida, A. et al. Successful management of a cesarean scar defect with dehiscence of the uterine incision by using wound lavage. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 421014 (2014).

Shimabukuro, T. T. et al. Preliminary findings of mRNA Covid-19 vaccine safety in pregnant persons. N. Engl. J. Med. 384(24), 2273–2282 (2021).

Barouch, D. H. Covid-19 vaccines—immunity, variants, boosters. N. Engl. J. Med. 387(11), 1011–1020 (2022).

Kharbanda, E. O. et al. Spontaneous abortion following COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy. JAMA. 326(16), 1629–1631 (2021).

Lipkind, H. S. et al. Receipt of COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy and preterm or small-for-gestational-age at birth—eight integrated health care organizations, United States, December 15, 2020–July 22, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 71(1), 26–30 (2022).

Moro, P. L. et al. Post-authorization surveillance of adverse events following COVID-19 vaccines in pregnant persons in the vaccine adverse event reporting system (VAERS), December 2020–October 2021. Vaccine. 40(24), 3389–3394 (2022).

Zauche, L. H. et al. Receipt of mRNA Covid-19 vaccines and risk of spontaneous abortion. N. Engl. J. Med. 385(16), 1533–1535 (2021).

Magnus, M. C. et al. Covid-19 vaccination during pregnancy and first-trimester miscarriage. N. Engl. J. Med. 385(21), 2008–2010 (2021).

Ruderman, R. S. et al. Association of COVID-19 vaccination during early pregnancy with risk of congenital fetal anomalies. JAMA Pediatr. 176(7), 717–719 (2022).

Perl, S. H. et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies in breast milk after COVID-19 vaccination of breastfeeding women. JAMA. 325(19), 2013–2014 (2021).

Akafa, A. T., Amos, Y., Okeke, A. & Oreh, A. C. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 transmission and preventive measures among residents of Nigeria: A population-based survey through social media. West Afr. J. Med. 38(4), 347–358 (2021).

Al-Regaiey, K. A. et al. Influence of social media on parents’ attitudes towards vaccine administration. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 18(1), 1872340 (2022).

Chin, C. Y., Liu, C. P. & Wang, C. L. Evolving public behavior and attitudes towards COVID-19 and face masks in Taiwan: A social media study. PLoS ONE. 16(5), e0251845 (2021).

Jogezai, N. A. et al. Teachers’ attitudes towards social media (SM) use in online learning amid the COVID-19 pandemic: The effects of SM use by teachers and religious scholars during physical distancing. Heliyon. 7(4), e06781 (2021).

Digital documentation of COVID-19 certificates: vaccination status: technical specifications and implementation guidance, 27 August 2021 available in: WHO-2019-nCoV-Digital-certificates-vaccination-2021.1-eng.pdf. (World Health Organization).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, for its funding support (grant number [IO] R016533023). We also appreciate the administrative support provided by Ms Nattacha Palawat. Finally, we are indebted to Mr David Park for the English-language editing of this paper.

Funding

The Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, provided funding support ([IO] R016533023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C. contributed to the conception and design of the research; the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript; and the approval of the final manuscript. S.A. contributed to the recruitment of the patients, revision of the manuscript, and approval of the final manuscript. A.K. contributed to the transcription of data from the audio recordings and approval of the final manuscript. J.P. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript, and final manuscript approval. V.T. contributed to the approval of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Each author has completed the Uniform Disclosure Form for Potential Conflicts of Interest prepared by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (Si1018/2021) and the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written, informed consent was obtained from all participants. I declare that the authors have no competing interests as defined by BMC, or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and/or discussion reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chawanpaiboon, S., Anuwutnavin, S., Kanjanapongporn, A. et al. A qualitative study of pregnant women’s perceptions and decision-making regarding COVID-19 vaccination in Thailand. Sci Rep 14, 5128 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55867-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55867-z

Keywords

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.