Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to many changes in the medical practice, including a wider access to tele-consultations. It not only influenced the type of treatment but also shed light on mistakes often made by doctors, such as the abuse of antibiotics. This study aimed to evaluate the antibiotic treatment, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on antibiotic prescribing during a GP’s visit. The retrospective medical history analysis involved data from a first-contact medical center (Pantamed, Olsztyn, Poland), from 1 January 2018 to 31 May 2023. Quantities of prescribed antibiotics were assessed and converted into the so-called active list for a given working day of adult patients (> 18 years of age). Statistical analysis based on collective data was performed. During the COVID-19 pandemic, a decline in the number of medical consultations has been observed, both remotely via tele-medicine and in personal appointments, compared to the data from before the pandemic: n = 95,251 versus n = 79,619. Also, during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a decrease in the total amount of prescribed antibiotics relative to the data before the pandemic (2.44 vs. 4.54; p > 0.001). The decrease in the quantities of prescribed antibiotics did not depend on the way doctor consultations were provided. The COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to changing the family doctors’ management of respiratory infections. The ability to identify the etiological agent—the SARS-COV2 virus—contributed to the reduction of the antibiotics use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

On 11 March 2020, WHO announced the outbreak of a pandemic caused by a coronavirus (COVID-19), a disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). This disease can be asymptomatic, with only mild symptoms, mainly from the respiratory tract, or can lead to acute respiratory insufficiency. In uncomplicated cases, as an isolated viral infection, it requires the treatment of symptoms, which is a contraindication to antibiotics use. The widespread availability of tests to detect the SARS-CoV-2 virus enabled simple and rapid diagnosis of this illness, which should also help to reduce the administration of antibiotics. Overuse of antibiotics leads to various complications, with microbiological resistance being one of the most significant1. According to the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), more than 2.8 million antibiotic-resistant infections occur in the United States each year, and more than 35,000 people die as a result2. It is estimated that the global consumption of antibiotics rose by circa 65% between 2000 and 20153. The increase in antibiotic consumption between 2019 and 2020 in the USA resulted in a 15% rise in antibiotic resistance, contributing to a higher number of deaths, primarily due to nosocomial infections1.

With a similar range of symptoms, viral infections of the upper respiratory tract are conducive to a belief that a common cold or influenza is an indication for antibiotic treatment4,5,6,7,8. Most patients do not understand the notion of antibiotic resistance. According to Brookes-Howell et al., as many as 35% of patients attribute the resistance to antibiotics to themselves (‘this antibiotic doesn’t work for me’)9. It is estimated that over 30% of patients in Poland occasionally resort to self-medication with antibiotics, which confronts doctors with a very difficult decision (no possibility of making a retrograde assessment) to discontinue treatment10. Consumption of antibiotics is seasonal, increasing in winter months and decreasing in early spring and summer, which is associated with a rise in influenza-like infections11,12,13.

The purpose of this study has been to evaluate the use of antibiotics in the first-contact doctor’s office, and to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on prescribing antibiotics.

Material and method

In order to reliably verify the recommended antibiotic therapy, data from the National Health Fund (NFZ), which is the healthcare payer in Poland, were used. The doctor-payer communication channel is used to transmit information about e-prescriptions issued. Each information package of this kind contains both the EAN code of a prescription and its international classification called ATC (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System). This classification allows one to identify groups of drugs, and not just to see their trade or chemical names. For example, macrolides are coded as J01FA15. This information is encoded in every medical prescription and is therefore available for analysis, which was taken advantage of in our database.

The most recent data (on 2 April 2023) issued by the Ministry of Health, in Poland, indicate that 35 924 946 tests for COVID-19 had been used14. Thus, the COVID-19 pandemic seems to have been an ideal period (a natural experiment) to verify the therapeutic choices of doctors regarding antibiotics and antibiotic-based treatment.

Data collection methodology

A family doctor in Poland works on the so-called active list (people who have chosen a doctor/clinic). This list is quite stable, but in a practice with several thousand people it changes by about 100 people a month (enrolled, discharged, deceased). In addition to these admissions, the family doctor is obliged to provide assistance to people who seek medical help but and live in another part of the country (e.g. people looking for medical consultation during holidays). The program built a database consisting of the active list and omitting ad hoc visits. The prerequisite was that the patient in a given month was under the care of the clinic for the entire month. People who signed up or resigned due to other reasons during a given month were not included in that month. The program generated a database for each subsequent month from 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2022. Then, these databases were merged. The maximum date of birth was also determined for each month (so as not to include persons under 18 years of age). By building monthly databases, the program added the occurrence of events specified in the search to the patient (if any). To avoid double coding of the same diseases, arbitrary minimum time intervals were adopted (Table Z—supplementary files). In Poland, where the national healthcare is free for the patient, it happens quite often that a patient diagnosed with a viral infection visits his family doctor 2–3 times in a short period of time (for example, on Monday he is examined but refuses to take a sick leave, on Tuesday he returns to claim his sick leave and on Wednesday he makes another appointment because he is convinced that he will not be cured without antibiotics). To account for such patterns, the assumed intervals were 30 days for COVID-19, 7 days for other viral infections, 14 days for illnesses suggesting a bacterial background, and a 10-day interval for antibiotics (for details, see Table Z—supplementary files). The program treated repeated events within a time shorter than the specified minimum interval as one. A case was included in the analysis if the product of events was met, thus urinary tract infections for example were excluded from the analysis (no ICD-10 code searched, ATC code searched).

The retrospective cross-sectional analysis included medical data of adults, i.e. aged 18 and older (on the date of the visit), who visited a doctor, either in the form of a remote consultation (tele-admission understood as tele-consultation) or as an on-site visit, from 1 January 2018 to 31 May 2023. In that period, the medical clinic Pantamed, Olsztyn, Poland, served an active list of patients aged over 18 years from 11 341 to 12 615 persons. In total, 716 242 records with data from medical consultations were submitted to the analysis.

All collected data were divided into 3 groups: before the COVID-19 pandemic (1 January 2018–31 May 2020), during the pandemic (1 June 2020–30 June 2022), and after the COVID-19 pandemic (1 July 2022–31 May 2023). The selection of the date of the actual (not official) termination of the pandemic (or its influence on the operation of first-contact medical centers) was based on the analysis of a biplot of discriminant, which confirmed that 93.9% of data were classified correctly.

Statistical analyses

To determine the level of antibiotic use in three periods over 2019–2023, namely: before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic, the index of average antibiotic consumption was related to a daily intake by a patient aged 18 years. To statistically evaluate the significance of differences in consumption of seven antibiotic groups, such as β-lactams (J01C), amoxicillin + clavulonian acid(J01CR), macrolides (J01F), azithromycin (J01FA10), tetracyclines (J01A), and quinolones (J01M), in the three periods, one-way analysis of variance followed the test for normality distribution of variables (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, p < 0.05).

In the procedure to detect variations in antibiotic consumption, a univariate ANOVA was employed to determine if there were statistically significant differences between the means of each group of antibiotics in three COVID-related periods. The differences were analyzed with a multiple comparison test (HSD Tukey's test, df = 62) as a post-hoc procedure.

Afterwards, linear discriminant analysis (DA) was implemented to determine if the time data were properly classified to the COVID-related periods (before, during, and post-COVID-19 pandemic). The use of DA enabled us to verify the accuracy of the a priori classification of COVID-related groups: before, during, and after the pandemic. DA was performed based on both frequencies of patient tele- and on-site admissions as well as the use of 6 antibiotics.

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistica™ 13.1 (TIBCO Software Inc. Palo Alto, US, 2021) and Past 4.0316.

Ethics

The study presented in this paper is a retrospective analysis of patients' medical records, in which no personal data of the patients were used or processed. Because the study was retrospective, written informed consent could not be received from all patients.

An ethics approval from the Bioethics Committee at the Warmia and Masuria Medical Chamber in Olsztyn (Resolution No. 30/2023/VIII) was obtained, and informed consent was waived by the approving ethics committee. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

In this study, patients ≥ 18 years old comprised a group of 87.3% of the whole population considered. The share of patients ≥ 18 during the pre-Covid period amounted to 88.0%, 89.2% during the Covid pandemic, and 82.6% in the post-Covid period (Table 1). Before the COVID-19 pandemic, patients at least 18 years old were given 1,183 medical consultations online, which corresponded to 1.2% of all consultations, and 94,068 on-site consultations (98.8%). During the pandemic, there were 44,454 (55.8%) and 35,165 (44.2%) online and on-site consultations, respectively, and after the pandemic, the respective figures were 5,544 (23.8%) and 35,069 (76.2%).

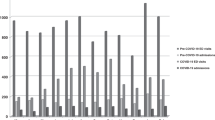

Figure 1 shows data concerning the number of admissions in each of the analyzed months, divided into the types of visits: on-site and tele-medicine, and the total number of consultations.

Discriminant analysis (DA), a multivariate statistical technique, allowed the classification of the antibiotic consumption rate (per person per month), and provided the best separation of the temporal groups previously (a priori) defined: before, during, and after COVID-19 (Fig. 2a). Based on the 65 sets of monthly data concerning the use of 6 antibiotics and the type of consultation with patients, DA (Fig. 2b) showed that the three predefined groups were correctly assigned 93.9% of the time and 88% when cross-validated by the jackknife principle.

(A) Biplot of discriminant analysis (DA) showing the classification of monthly rates of antibiotic use in pre-COVID, during COVID, and post-COVID periods. (B) Summary of classification given and predicted temporal groups with jackknife cross-validation. (C) Confusion matrix for given and predicted pre-COVID, COVID, and post-COVID groups with quality of the classification.

A significant decrease in the number of visits (both on-site and tele-consultations) and the number of consultations provided in the doctor's office was evident during the COVID-19 pandemic During that period, a new form of medical service emerged, namely tele-admission, which remains available after the pandemic. However, the number of tele-consultations since May 2020 has remained low, accounting for only about 11% of the total number of admissions.

Due to fluctuations in the number of patients registered with the clinic, which can result from factors such as deaths or transfers to other clinics providing basic medical care, the authors utilized an indicator. This indicator is calculated as the quotient of the number of events (visits to the clinic) divided by the total number of registered patients on a given day, multiplied by the number of working days in a given month. Based on this indicator, Table 2 presents data regarding the use of antibiotics, categorized into three periods: before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 3 presents cumulative data on antibiotic usage. The diagram illustrates a notable reduction in antibiotic prescriptions, particularly noticeable for all β-lactams and macrolides, including azithromycin, during the pandemic, particularly in its first year.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on the entire healthcare sector. For epidemiological reasons, tele-consultations, which were previously rarely used in the state healthcare system, became essential to maintain the continuity of medical services.. As shown in Fig. 1, there was a substantial increase in remote healthcare services in March 2020, coinciding with a decrease in patients' visits to GP's offices. As the pandemic escalated, the primary focus shifted to the care of COVID-19 patients, leading to a significant reduction in face-to-face consultations with doctors, primarily limited to emergency cases, in order to minimize the risk of disease transmission between doctors and patients17. Between June and September 2021, this trend began to reverse, with a decrease in tele-admissions and a return to on-site admissions in clinics. At the same time, according to data issued by the Ministry of Health in Poland, the pandemic came to a halt, and the number of new cases was in the range of 100–200 new cases/day18.

In December 2020, COVID-19 vaccines became available in Poland, and the highest vaccination coverage of the population was achieved by the spring of 2021, contributing to a renewed increase in the number of on-site medical consultations19.

COVID-19 is a viral infection caused by the SARS-CoV2 virus, which can be treated with such antiviral medications as nirmatrelvir, ritonavir, remdesivir, and molnupiravir20,21,22,23. According to the data presented in this article, there was a significant reduction in the administration of antibiotics from January to April 2020. However, in October 2020, the use of antibiotics began to gradually increase. At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a decrease in the overall use of antibiotics (Fig. 3).

The results presented in Table 1 indicate a noticeable difference in antibiotic use before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Relative to the period preceding the pandemic, the number of prescribed antibiotics during the pandemic decreased, both in total and divided into groups of antibiotics. This trend is observed for each analyzed group of antibiotics.However, there is a discernable difference in the use of antibiotics before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, applying to each prescribed antibiotic.

The gradual increase in the quantities of prescribed antibiotics observed later during the COVID-19 pandemic may be attributed to subsequent waves of the pandemic and secondary bacterial complications.. Shafran et al., based on data collected from hospitalized patients, demonstrated that patients with COVID-19 had more documented secondary bacterial infections than patients with influenza, and these infections were not correlated with the death of patients with COVID-19, but not in patients with influenza24. On the other hand, Nandi et al. demonstrated that the bacterial co-infection index for patients with COVID-19 was lower than 10%, yet antibiotics were prescribed to over 75% of COVID-19 patients25. This approach is linked to the development of antimicrobial resistance. The CDC estimates that from 30 to 50% of all antibiotics prescribed in ambulatory care are unnecessary2.

An article published in Lancet in February 2020 contained an analysis of monthly data from the company IQUVIA MIDAS regarding sales volumes of four groups of broad-spectrum antibiotics: cephalosporins, penicillin, macrolides, and tetracyclines (ATC classification was employed)25,26. This article, based on data from 71 countries covering the period from January 2018 to May 2020, showed that the sales of all four groups of antibiotics decreased rapidly in April and May 2020. Since May 2020, there has been a gradual increase up to the level similar to that before the pandemic. Another high-impact journal article, authored by Allard et al. in 2023, showed that antibiotic use increased during the COVID-19 pandemic; however, this study focused only on data from hospitalized patients3. The apparent contradiction between these two studies can be explained by our results, based entirely on data from an outpatient clinic. It is worth noting that the clinic returned to its normal work in the final stage of the pandemic. Arbitrarily assuming its end date (May 5, 2023, according to WHO) would be an error in our analysis27. Our data (Fig. 2) suggest that the actual end of the direct impact of the pandemic on the healthcare system in our country occurred in March/April 2022. Figure 2, which demonstrates that 93.9% of cases were correctly classified according to the time intervals assumed in our study, supports our assumption.

Our study has a few limitations. First of all, it is a retrospective study conducted in one healthcare center, and its results depend on the accuracy of the center's medical records and diagnosis coding. The study may also be affected by selection bias, as the decision to prescribe antibiotics was made by individual doctors based on their subjective assessment of the severity of each case and the overall clinical picture of the patient. In a retrospective assessment, as explained above, it is impossible to question the reasons for these earlier decisions. Secondly, considering the local screening policy, not every admitted patient was tested for COVID-19, and there is a possibility that some COVID-19 test results may have been falsified by patients during tele-admission visits to avoid isolation. However, the picture of antibiotic use emerging from the data presented in this article is difficult to challenge. In our opinion, widespread access to screening tests such as COVID-19 tests, and consequently, the confirmation of viral infections, had a positive impact on reducing antibiotic administration in outpatient healthcare.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic is a lesson for doctors in first-contact health clinics, showing that the reduction in the administration of antibiotics is possible and recommended. The amounts of antibiotics administered in outpatient health care decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic, and despite their slight increase later on, their prescribing remains lower than before the pandemic (Fig. 3). Our observations suggest that future research should carefully consider the timing of the pandemic, including its end date. Using an arbitrarily chosen end date, such as May 5, 2023, can potentially introduce inaccuracies in study findings.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Murray, C. J. et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. The Lancet 399, 629–655 (2022).

Be Antibiotics Aware: Smart Use, Best Care | Patient Safety | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/patientsafety/features/be-antibiotics-aware.html.

Klein, E. Y. et al. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, E3463–E3470 (2018).

Organization, W. H. Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance (2015).

Fernández-Montero, J. V., Corral, O., Barreiro, P. & Soriano, V. Use of antibiotics in respiratory viral infections. Intern. Emerg. Med. 17, 1569–1570 (2022).

Machado-Duque, M. E. et al. Antibiotic prescriptions for respiratory tract viral infections in the Colombian population. Antibiotics 10, 864 (2021).

Wilson, A. A., Crane, L. A., Barrett, P. H. & Gonzales, R. Public beliefs and use of antibiotics for acute respiratory illness. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 14, 658–662 (1999).

Fredericks, I. et al. Consumer knowledge and perceptions about antibiotics and upper respiratory tract infections in a community pharmacy. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 37, 1213–1221 (2015).

Brookes-Howell, L. et al. ‘The body gets used to them’: Patients’ interpretations of antibiotic resistance and the implications for containment strategies. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 27, 766–772 (2012).

Muras, M., Krajewski, J., Nocun, M. & Godycki-Cwirko, M. A survey of patient behaviours and beliefs regarding antibiotic self-medication for respiratory tract infections in Poland. Archiv. Med. Sci. 9, 854–857 (2013).

Sun, L., Klein, E. Y. & Laxminarayan, R. Seasonality and temporal correlation between community antibiotic use and resistance in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 55, 687–694 (2012).

Klein, E. Y. et al. The Impact of Influenza Vaccination on Antibiotic Use in the United States, 2010–2017. Open Forum Infect Dis 7, (2020).

Romaszko, J. et al. Applicability of the universal thermal climate index for predicting the outbreaks of respiratory tract infections: A mathematical modeling approach. Int. J. Biometeorol. 63, 1231–1241 (2019).

Raport zakażeń koronawirusem (SARS-CoV-2) - Koronawirus: informacje i zalecenia - Portal Gov.pl. https://www.gov.pl/web/koronawirus/wykaz-zarazen-koronawirusem-sars-cov-2.

Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification. https://www.who.int/tools/atc-ddd-toolkit/atc-classification.

Hammer, D. A. T., Ryan, P. D., Hammer, Ø. & Harper, D. A. T. Past: Paleontological Statistics Software Package for Education and Data Analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica vol. 4 http://palaeo-electronica.orghttp://palaeo-electronica.org/2001_1/past/issue1_01.htm. (2001).

Ochal, M., Romaszko, M., Glińska-Lewczuk, K., Gromadziński, L. & Romaszko, J. Assessment of the consultation rate with general practitioners in the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 1–9 (2020).

Koronawirus w Polsce - aktualne oraz historyczne dane i wykresy. https://koronawirusunas.pl/.

Soraci, L. et al. COVID-19 vaccines: Current and future perspectives. Vaccines (Basel) 10, 608 (2022).

Niknam, Z. et al. Potential therapeutic options for COVID-19: An update on current evidence. Eur. J. Med. Res. 27, 1–15 (2022).

Jayk Bernal, A. et al. Molnupiravir for oral treatment of Covid-19 in nonhospitalized patients. New England J. Med. 386, 509–520 (2022).

Cao, Z., Gao, Y. & Zhao, R. VV116 or nirmatrelvir-ritonavir for oral treatment of covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 2396–2397 (2023).

Beigel, J. H. et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 1813–1826 (2020).

Shafran, N. et al. Secondary bacterial infection in COVID-19 patients is a stronger predictor for death compared to influenza patients. Sci Rep 11, 12703 (2021).

Nandi, A., Pecetta, S. & Bloom, D. E. Global antibiotic use during the COVID-19 pandemic: Analysis of pharmaceutical sales data from 71 countries, 2020–2022. EClinicalMedicine 57, (2023).

MIDAS® - IQVIA. https://www.iqvia.com/solutions/commercialization/brand-strategy-and-management/market-measurement/midas.

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

Funding

Funded by the Minister of Science under „the Regional Initiative of Excellence Program”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.R.W. designed the study, conceived the original idea, acquired the data, wrote the manuscript, and reviewed the final manuscript. K.T.M. acquired the data and reviewed the final manuscript. A.D. supervised the project and reviewed the final manuscript. K.G.L. conducted all statistical analyses and reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Romaszko-Wojtowicz, A., Tokarczyk-Malesa, K., Doboszyńska, A. et al. Impact of COVID-19 on antibiotic usage in primary care: a retrospective analysis. Sci Rep 14, 4798 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55540-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55540-5

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.