Abstract

Ramucirumab plus docetaxel (RD) can cause febrile neutropenia (FN), which frequently requires the prophylactic administration of pegfilgrastim. However, the effects of prophylactic pegfilgrastim on FN prevention, therapeutic efficacy, and prognosis after RD have not been fully evaluated in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Two hundred and eighty-eight patients with advanced NSCLC who received RD as second-line therapy after platinum-based chemotherapy plus PD-1 blockade were included. Patients were divided into groups with and without prophylactic pegfilgrastim, and adverse events, efficacy, and prognosis were compared between both groups. Of the 288 patients, 247 received prophylactic pegfilgrastim and 41 did not. The frequency of grade 3/4 neutropenia was 62 patients (25.1%) in the pegfilgrastim group and 28 (68.3%) in the control group (p < 0.001). The frequency of FN was 25 patients (10.1%) in the pegfilgrastim group and 10 (24.4%) in the control group (p = 0.018). The objective response rate was 31.2% and 14.6% in the pegfilgrastim and control groups (p = 0.039), respectively. The disease control rate was 72.9% in the pegfilgrastim group and 51.2% in the control group (p = 0.009). Median progression free survival was 4.3 months in the pegfilgrastim group and 2.5 months in the control group (p = 0.002). The median overall survival was 12.8 and 8.1 months in the pegfilgrastim and control groups (p = 0.004), respectively. Prophylactic pegfilgrastim for RD reduced the frequency of grade 3/4 neutropenia and febrile neutropenia and did not appear to be detrimental to patient outcome RD.

Clinical Trial Registration Number: UMIN000042333.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ramucirumab plus docetaxel (RD) therapy is an option for patients with previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). A randomized phase 3 study (REVEL) demonstrated significantly better overall survival (OS) than with docetaxel alone in patients with previously treated NSCLC1. Real-world data (NEJ051, REACTIVE) of 288 RD-treated patients with NSCLC in second-line treatment after chemoimmunotherapy showed an objective response rate of 28.8% (95% confidence interval (CI):23.7–34.4)2. Therefore, RD is a confirmed as one of treatment options for patients with previously treated advanced NSCLC.

Besides, a phase 2 study (JVCG) of RD in Japan reported a high frequency of neutropenia and febrile neutropenia (FN)3. The frequency of all-grade neutropenia in the JVCG study was 94.7%3. The frequency of grade 3 or higher neutropenia and FN have previously been reported as 89.5% and 34.2%, respectively3. Although the docetaxel dose was 60 mg/m2 in Japan, hematological toxicity was observed more frequently than that in the REVEL study, requiring palliative management.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines recommend the prophylactic use of granulocyte colony stimulating factors (G-CSFs) when the risk of FN exceeds 20%4. Pegfilgrastim (PEG) is a long-acting preparation that has a prolonged blood elimination half-life owing to the chemical binding of polyethylene glycol to the N-terminus of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)5. PEG is subcutaneously administered at a dose of 3.6 mg once on day 2 per chemotherapy cycle. One small prospective study reported that the incidence of FN with PEG in RD therapy was 5%6, and several retrospective studies have described the incidence of FN as 0–7.4%7,8,9,10,11. Although these exploratory studies identified the prevention of FN in RD therapy by the administration of PEG, the sample sizes of these previous investigations were limited; thus, it remains unclear whether the clinical usefulness of PEG in RD treatment could be confirmed as standard care. Aside from the preventive effect of FN after RD treatment, there is insufficient evidence to determine whether PEG could affect the efficacy and outcome of RD. A large sample size is needed to elucidate the clinical utility of PEG prophylaxis after RD initiation. Based on this background, we conducted a post-hoc analysis to evaluate the clinical significance of PEG prophylaxis after the initiation of RD in patients with previously treated NSCLC using a large sample size, as previously described2.

Results

Patient demographics

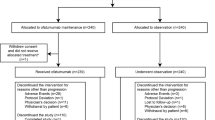

Table 1 shows the demographics of patients classified according to the presence or absence of PEG treatment. Two hundred and forty-seven patients (85.8%) received prophylactic PEG treatment, and 41 (14.2%) (control group) did not. The number of patients with a history of smoking was significantly higher in the control group than in the PEG group (p = 0.025). There were no significant differences in other factors. Of the 247 patients with PEG prophylaxis, 223 (90.3%) underwent prophylaxis during the first cycle of RD and 24 (9.7%) during the second cycle. Therefore 65 patients (41 control plus 24 s cycle) did not receive PEG prophylaxis during the first cycle of RD. Table 2 shows the characteristics of the patients who did/did not receive PEG prophylaxis during the first cycle. The proportion of patients aged ≥ 75 years was significantly higher in the PEG than in the control group (p = 0.013). The number of patients with a history of smoking was significantly higher in the control than in the PEG group (p = 0.043). There were no statistically significant differences in other factors.

Implementation status of drug delivery

The starting dose of docetaxel for RD was 60 mg/m2 in 270 (93.8%) patients and < 60 mg/m2 in 18 (6.3%) patients. Of the 247 patients with PEG prophylaxis, the docetaxel dose was 60 mg/m2 in 233 (94.3%) and < 60 mg/m2 in 14 (5.7%). Of the 41 controls, the docetaxel dose was 60 mg/m2 in 37 (90.2%) and < 60 mg/m2 in 4 (9.8%) patients. The median number of RD cycles in all patients was 4 (range, 1–22). The median number of RD cycles with and without PEG prophylaxis was 5 (range, 1–22) compared with 2 (range, 1–19) for patients without PEG prophylaxis (p = 0.019). RD treatment was discontinued in 270/288 patients (93.8%); 93.9% (232/247 patients) in the PEG group and 92.7% (38/41 patients) in the control group. Sixty-three (27.2%) of 232 PEG-treated patients and 10 (26.3%) of the 38 control patients discontinued treatment. The majority of these patients discontinued due to progressive disease and AE.

Therapeutic efficacy

Table 3 shows the efficacy of RD. The ORR and DCR for RD were 28.8% (95% CI 23.7–34.4) and 69.8% (95% CI 64.1–75.0), respectively. The ORR was 31.2% (95% CI 25.7–37.2) in the PEG group and 14.6% (95% CI 6.5–28.8) in the control group (p = 0.039). DCR was 72.9% (95% CI 67.0–78.0) in the PEG group and 51.2% (95% CI 36.5–65.7) in the control group (p = 0.009). Table S2 compares the efficacy in patients with and without PEG prophylaxis after the first cycle of RD. The ORR was 31.4% (95% CI 25.6–37.8) in the PEG group (n = 223) and 20.0% (95% CI 11.9–31.4) in the control group (n = 65) (p = 0.087). DCR was 72.2% (95% CI 66.0–77.7) in the PEG group and 61.5% (95% CI 49.4–72.4) in control group (p = 0.124).

Survival analysis

Figure 1 shows Kaplan–Meier curves for PFS and OS classified according to whether prophylactic PEG was administered or not. Median PFS was 4.3 months (95% CI 3.9–4.8) in the PEG group and 2.5 months (95% CI 1.1–3.9) in the control group (significant difference (HR 0.57; 95% CI 0.40–0.81; p = 0.002)). Median OS was 12.8 months (95% CI 10.7–14.9) in the PEG group and 8.1 months (95% CI 5.0–11.2) in the control group [significant difference (HR 0.63; 95% CI 0.41–0.96; p = 0.004)]. Figure S1 shows the Kaplan–Meier survival curves with and without PEG administration after the first cycle. Median PFS was 4.4 months (95% CI 3.9–4.8) in the PEG group and 3.4 months (95% CI 2.7–4.0) in the control group (significant difference (HR 0.77; 95% CI 0.58–1.03; p = 0.022)). Median OS was 13.8 months (95% CI 11.8–15.8) in the PEG treatment group and 8.7 months (95% CI 7.2–10.1) in the control group (significant difference (HR 0.63; 95% CI 0.44–0.90; p = 0.001)). Figures S2 and S3 show the Kaplan–Meier survival curves according to PEG administration in the adenocarcinoma (AC) and non-adenocarcinoma (non-AC) groups. Figures S4 and S5 show the Kaplan–Meier survival curves based on PEG administration after the first cycle among the different histology. The PFS was not significantly different between the PEG prophylaxis and control groups in AC patients, but a statistically significant difference was observed between groups in PFS and OS for non-AC patients and OS for AC patients.

Kaplan–Meier curves showing progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) classified according to the presence or absence of prophylactic pegfilgrastim (PEG) in ramucirumab plus docetaxel treatment. Median progression free survival was 4.3 months (95% CI 3.9–4.8) in the PEG prophylaxis group and 2.5 months (95% CI 1.1–3.9) in the control group (p = 0.002). Median overall survival was 12.8 months (95% CI 10.7–14.9) in the PEG prophylaxis group and 8.1 months (95% CI 5.0–11.2) in the control group (p = 0.004).

Relationship between first-line treatment and RD

The PFS (175 days vs. 167 days, p = 0.095) and ORR (55.1% vs. 43.9%, p = 0.236) to first-line treatments were not significantly different between the patients who used and did not use PEG. Moreover, the response of PR or CR to first-line treatments was observed in 54 (70.1%) of 77 patients and 4 (66.7%) of 6 patients with CR or PR to RD in the PEG group and control group, respectively, without statistical significance.

Adverse events

Table 4 shows hematological toxicities. The frequencies of grade 3/4 leukopenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and FN in all patients were 23.6%, 6.3%, 2.1%, 31.3%, and 12.2%, respectively. The frequencies of grade 3/4 leukopenia were 21.5% in the PEG prophylaxis group and 36.6% in the control group (p = 0.046), those of grade 3/4 neutropenia were 25.1% in the PEG group and 68.3% in the control group (p < 0.001), and those of FN were 10.1% in the PEG prophylaxis group and 24.4% in the control group (p = 0.018). No statistically significant differences were observed in the non-hematological AE between the PEG and control groups (Table 5).

Discussion

This post-hoc analysis identified the clinical usefulness of prophylactic PEG in patients with advanced NSCLC who received RD immediately after PD-1 blockade plus platinum-based chemotherapy. We found that the frequency of FN was 10.1% in the PEG prophylaxis group and 24.4% in the control group. The incidence of FN in the REVEL and JVCG studies was 16% and 34.2%, respectively1,3. The incidence of FN in patients who underwent prophylactic PEG in our study was lower than that reported in previous prospective studies1,3. Although there were no significant differences in the patient characteristics between the two groups, prophylactic PEG potentially improved compliance with RD administration by preventing the occurrence of FN. Our large-scale study confirmed that prophylactic PEG can improve the therapeutic efficacy and minimize the toxicity of RD treatment after first line chemoimmunotherapy. However, we guess that the different incidence of FN between JVCG and REVEL study may be caused by the ethnic different between Caucasian and Asian patients. Therefore, we should recommend the use of prophylactic PEG only to Asian patients.

Several studies have described the palliative usefulness of RD treatment for FN prevention5,7,8,9,10,11. When prophylactic PEG was administered for RD treatment, the incidence of FN was < 10%, with an average of approximately 5%5,7,8,9,10,11. Without prophylactic PEG, the incidence of FN was approximately 25%7,8,10,11. Considering the results of previous and current studies, prophylactic PEG immediately after RD treatment should be considered routinely necessary for the prevention of FN and the continuous administration of RD. A retrospective study has reported that the prophylactic use of PEG reduced the hospitalization rate for multiple cancer types12. In our study, the number of dosing cycles of RD tended to be higher in the PEG group, although the frequency of discontinuation due to AE or progressive disease was similar in the PEG prophylaxis and PEG control groups. The optimal timing for chemotherapeutic administration of prophylactic PEG may affect the efficacy and prognosis of RD treatment. Mouri et al. compared the efficacy and outcome of RD between 29 patients with PEG prophylaxis and 4 patients without8. Because of the very small size of the control group, the ORR, PFS, and OS were not significantly different between the two groups. Moreover, Sakaguchi et al. reported that 95 of their 114 (83.3%) patients received prophylactic PEG, whereas 19 (16.7%) did not9. Although their study did not include information regarding the incidence of FN in the control group, the use of prophylactic PEG was significantly associated with favorable PFS and OS9. However, there are several concerns about previous studies. The number and regimens of prior treatments before RD initiation differed in each study, and there was no uniformity in prior immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) treatment. A recent study suggested the potential for increased efficacy of RD by prior ICI treatment13. Considering the regimens used in previous studies8,9, prior immunotherapy may affect the therapeutic efficacy of RD treatment, regardless of the administration of prophylactic PEG. In our study, the regimen administered just before RD was unified as PD-1 blockade plus platinum-based chemotherapy. Interestingly, we found that prophylactic PEG affected the therapeutic efficacy of RD immediately after chemoimmunotherapy. A recent preclinical study demonstrated that PEG enhances the antitumor activity of immunotherapy with antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) or phagocytosis (ADCP)14. As a possible mechanism, stimulation with PEG was related to significant enhancement of leukocytes in the spleen and the mobilization of activated monocytes or granulocytes from the spleen to the tumor bed14. Although it remains unknown whether PEG could potentiate the antitumor activity of PD-1 blockade, the synergistic relationship between PEG and prior immunotherapy is an interesting topic requiring further investigation to elucidate a possible mechanism. Currently, immunotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy are the standard first-line treatments for the care of patients with advanced NSCLC. Unlike previous studies, our study included all patients receiving first-line chemoimmunotherapy. Therefore, our population size meets the requirements for actual clinical practice and will be helpful to physicians.

A new device for convenient PEG administration has been developed. An on-body injector (OBI) is a device worn by patients after chemotherapy that automatically administers PEG approximately 27 h later15. OBI was not inferior to conventional manual injection in terms of pharmacokinetic safety15. Prospective studies in breast cancer, prostate cancer, lung cancer, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma have reported that the OBI reduces neutropenia compared with conventional FN strategies16. The use of the OBI has been suggested to improve adherence and compliance. Thus, preventive effects of the OBI on FN are expected in patients with cancer receiving strong myelosuppressive chemotherapy.

This study has limitations. First, the number of patients in the PEG (n = 247) and control groups (n = 41) was unbalanced because of a retrospective sub-analysis. Second, we could not determine the reasons for choosing PEG, as the decision to use prophylactic PEG depended on the physicians at each institution. An imbalance in the patients in each group may have affected the results of our study. This difference between the PEG prophylaxis and control groups may be associated with differences in efficacy and outcomes of RD treatment. Finally, we could not collect information on whether patients had undergone filgrastim treatment at neutropenia or FN onset in the control group. Future prospective comparative studies are required to verify the therapeutic efficacy and outcomes of PEG prophylaxis in RD treatment. This study is a retrospective assessment, and the major difference between the patients who received and did not receive PEG depended on the judgment of chief physicians at different institutions. No precious definition of PEG administration remains unclear, thus, it may bias the results of our study.

Prophylactic PEG for RD therapy significantly reduced the frequency of neutropenia and FN in patients with advanced NSCLC after chemotherapy. The use of prophylactic PEG does not appear to be detrimental to patient outcome of RD in such patients. Prophylactic PEG is clinically recommended for the prevention of FN after RD.

Methods

Design

A total of 62 Japanese institutions participated in this post-hoc analysis (OnlineAppendix Table S1). We identified 288 patients who received RD as second-line therapy after first-line platinum-based chemotherapy plus PD-1 blockade therapy between January 2017 and August 2020. Our analysis was performed using the same sample as that used in a previously described study2. The following were administered as first-line treatments:

-

Pembrolizumab plus cisplatin or carboplatin plus pemetrexed therapy (KEYNOTE-189)17;

-

Pembrolizumab plus carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel or paclitaxel therapy (KEYNOTE-407)18;

-

Atezolizumab plus carboplatin plus paclitaxel plus bevacizumab therapy (IMpower150)19;

-

Atezolizumab plus carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel therapy (IMpower130)20; or

-

Atezolizumab plus carboplatin plus pemetrexed therapy (IMpower132)21.

Patients who received PEG prophylaxis after RD initiation were compared with those who did not. Clinical data up to March 31, 2021, were extracted from the medical records. This study was approved by the institutional ethics committees of Saitama Medical University International Medical Center. The requirement for informed consent was waived by the ethics committee of the Saitama Medical University International Medical Center owing to the retrospective nature of the study. We would like to confirm that all procedures and methodologies used in this study were carried out in strict compliance with the relevant guidelines and regulations as stipulated by the journal’s editorial policy. We have obtained all required permissions and have ensured that our methods are transparent, ethical, and rigorous.

Treatment and evaluation

All patients received combined chemotherapy with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies as first-line treatment. The KEYNOTE-18917, KEYNOTE-40718, IMpower15019, IMpower13020, and IMpower132 regimens21 were intravenously administered. RD (ramucirumab 10 mg/kg and docetaxel 60 mg/m2) was intravenously administered as second-line treatment. PEG (3.6 mg, G-LASTA™, Kyowa Kirin Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), a prophylactic granulocyte colony-stimulating factor used after RD initiation, was administered based on the judgement of the chief doctor at the individual institution, and its subcutaneous administration was performed per chemotherapy cycle in all patients.

Physical examinations, complete blood counts, biochemical tests, and the recording of adverse events (AE) were performed at the discretion of the chief physicians at the respective institutions. Toxicity was graded based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0. The tumor response was examined according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1.22.

Prognostic endpoints’ definition

The periods considered for overall survival (OS) versus progression free survival (PFS) events were as follows: initiation of RD till the date of mortality due to any cause versus initiation of RD till the dates of exacerbation or mortality due to any cause, or initiation of third-line treatment.

Statistics

To summarize the patient background and treatment results, we calculated the number of patients in each category and the median and maximum values in the continuous data. We further calculated the objective response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR); [%, 95% CI]. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to obtain the survival curves. The significance levels of the tests and confidence coefficients for interval estimation were 5% and 95%, respectively, on both sides. Fisher’s exact test was used to examine the association between categorical variables. GraphPad Prism (version 7.0; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and JMP 14.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA) were used for statistical analyses.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Garon, E. B. et al. Ramucirumab plus docetaxel versus placebo plus docetaxel for second-line treatment of stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer after disease progression on platinum-based therapy (REVEL): A multicentre, double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 384, 665–673 (2014).

Nakamura, A. et al. Multicentre real-world data of ramucirumab plus docetaxel after combined platinum-based chemotherapy with programmed death-1 blockade in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: NEJ051 (REACTIVE study). Eur. J. Cancer 184, 62–72 (2023).

Yoh, K. et al. A randomized, double-blind, phase II study of ramucirumab plus docetaxel vs placebo plus docetaxel in Japanese patients with stage IV non-small cell lung cancer after disease progression on platinum-based therapy. Lung Cancer 99, 186–193 (2016).

Smith, T. J. et al. Recommendations for the use of WBC growth factors: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 3199–3212 (2015).

Molineux, G. et al. The design and development of pegfilgrastim (PEG-rmetHuG-CSF, Neulasta). Curr. Pharm. Des. 10, 1235–1244 (2004).

Kasahara, N. et al. Administration of docetaxel plus ramucirumab with primary prophylactic pegylated-granulocyte colony-stimulating factor for pretreated non-small cell lung cancer: A phase II study. Support Care Cancer 28, 4825–4831 (2020).

Hata, A. et al. Docetaxel plus ramucirumab with primary prophylactic pegylated-granulocyte-colony stimulating factor for pretreated non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 9, 27789–27796 (2018).

Mouri, A. et al. Clinical significance of primary prophylactic pegylated-granulocyte-colony stimulating factor after the administration of ramucirumab plus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac. Cancer 10, 1005–1008 (2019).

Sakaguchi, T. et al. The efficacy and safety of ramucirumab plus docetaxel in older patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac. Cancer 11, 1559–1565 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Safety and effectiveness of ramucirumab and docetaxel: A single-arm, prospective, multicenter, non-interventional, observational, post-marketing safety study of NSCLC in Japan. Expert. Opin. Drug Saf. 21, 691–698 (2022).

Matsumoto, K. et al. Efficacy and safety of ramucirumab plus docetaxel in older patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A multicenter retrospective cohort study. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 13, 207–213 (2022).

Naeim, A. et al. Pegfilgrastim prophylaxis is associated with a lower risk of hospitalization of cancer patients than filgrastim prophylaxis: A retrospective United States claims analysis of granulocyte colony-stimulating factors (G-CSF). BMC Cancer 13, 11 (2013).

Shiono, A. et al. Improved efficacy of ramucirumab plus docetaxel after nivolumab failure in previously treated non-small cell lung cancer patients. Thorac. Cancer 10, 775–781 (2019).

Cornet, S. et al. Pegfilgrastim enhances the antitumor effect of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Mol. Cancer Ther. 15, 1238–1247 (2016).

Yang, B. B. et al. Comparison of pharmacokinetics and safety of pegfilgrastim administered by two delivery methods: On-body injector and manual injection with a prefilled syringe. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 75, 1199–1206 (2015).

Rifkin, R. M. et al. A prospective study to evaluate febrile neutropenia incidence in patients receiving pegfilgrastim on-body injector versus other choices. Support Care Cancer 30, 7913–7922 (2022).

Gandhi, L. et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 2078–2092 (2018).

Paz-Ares, L. et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for squamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 2040–2051 (2018).

Socinski, M. A. et al. Atezolizumab for first-line treatment of metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 2288–2301 (2018).

West, H. et al. Atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone as first-line treatment for metastatic non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower130): A multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 20, 924–937 (2019).

Nishio, M. et al. Atezolizumab plus chemotherapy for first-line treatment of nonsquamous NSCLC: Results from the randomized phase 3 IMpower132 trial. J. Thorac. Oncol. 16, 653–664 (2021).

Eisenhauer, E. A. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 45, 228–47 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Yuka Matsui (M-Techno Planning), Tomohiro Marui (M-Techno Planning), and Hisao Imai (M.D., PhD, Saitama Medical University International Medical Center) for their assistance with the manuscript. The authors also thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for the English language editing.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Eli Lilly Japan K.K.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.N.: Investigation; Writing original draft; Draft review and editing. O.Y.: Conceptualisation; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Writing original draft; Draft review and editing. K.M.: Conceptualisation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing original draft; Writing original draft; Draft review and editing. K.M.: Investigation; Draft review and editing. M.T.: Investigation; Draft review and editing. T.O.: Investigation; Draft review and editing. N.Y.: Investigation; Draft review and editing. H.M.: Investigation; Draft review and editing. T.N.: Investigation; Draft review and editing. T.K.: Investigation; Draft review and editing. K.I.: Investigation; Draft review and editing. A.M.: Investigation; Draft review and editing. D.A.: Investigation; Draft review and editing. H.K.: Investigation; Draft review and editing. K.K.: Conceptualisation; Methodology; Draft review and editing. K.K.: Conceptualisation; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Project administration; Writing original draft; Draft review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Keita Miura reports a relationship with Chugai Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Keita Miura reports a relationship with Taiho Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Kentaro Ito reports a relationship with Eli Lilly that includes speaking and lecture fees. Kentaro Ito reports a relationship with Boehringer Ingelheim that includes speaking and lecture fees. Kentaro Ito reports a relationship with Takeda Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Kentaro Ito reports a relationship with Chugai Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Kentaro Ito reports a relationship with Pfizer that includes speaking and lecture fees. Kentaro Ito reports a relationship with Merck & Co Inc. that includes speaking and lecture fees. Kentaro Ito reports a relationship with AstraZeneca that includes speaking and lecture fees. Kentaro Ito reports a relationship with Ono Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Kentaro Ito reports a relationship with Taiho Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Daisuke Arai reports a relationship with Chugai Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Daisuke Arai reports a relationship with AstraZeneka KK Tokyo Branch that includes speaking and lecture fees. Daisuke Arai reports a relationship with Ono Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Daisuke Arai reports a relationship with Taiho Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Daisuke Arai reports a relationship with Takeda Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Daisuke Arai reports a relationship with Nippon Kayaku Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Daisuke Arai reports a relationship with Merck & Co Inc that includes speaking and lecture fees. Kyoichi Kaira reports financial support was provided by Eli Lilly Japan KK. Kyoichi Kaira reports a relationship with AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP that includes speaking and lecture fees. Hiroaki Kodama reports a relationship with Chugai Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Hiroaki Kodama reports a relationship with Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc that includes speaking and lecture fees. Hiroaki Kodama reports a relationship with Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation that includes speaking and lecture fees. Kunihiko Kobayashi reports a relationship with AstraZeneca that includes speaking and lecture fees. Kunihiko Kobayashi reports a relationship with Takeda Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Atsushi Nakamura reports a relationship with MSD that includes speaking and lecture fees. Atsushi Nakamura reports a relationship with Thermo Fisher Scientific that includes speaking and lecture fees. Atsushi Nakamura reports a relationship with AstraZeneca that includes speaking and lecture fees. Atsushi Nakamura reports a relationship with Eli Lilly Japan KK that includes speaking and lecture fees. Atsushi Nakamura reports a relationship with Chugai Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Atsushi Nakamura reports a relationship with Taiho Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Atsushi Nakamura reports a relationship with Nippon Kayaku Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Atsushi Nakamura reports a relationship with Novartis Pharma that includes speaking and lecture fees. Takashi Ninomiya reports a relationship with Boehringer Ingelheim that includes speaking and lecture fees. Takashi Ninomiya reports a relationship with AstraZeneca that includes speaking and lecture fees. Takashi Ninomiya reports a relationship with Chugai Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Ou Yamaguchi reports a relationship with Eli Lilly Japan K.K. that includes speaking and lecture fees. Ou Yamaguchi reports a relationship with Ono Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Ou Yamaguchi reports a relationship with Bristol Myers Squibb Co that includes speaking and lecture fees. Ou Yamaguchi reports a relationship with Chugai Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Ou Yamaguchi reports a relationship with Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp that includes speaking and lecture fees. Ou Yamaguchi reports a relationship with AstraZeneca that includes speaking and lecture fees. Noriko Yanagitani reports a relationship with Chugai Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Noriko Yanagitani reports a relationshipwith Ono Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Noriko Yanagitani reports a relationship with Bristol Myers Squibb that includes speaking and lecture fees. Noriko Yanagitani reports a relationship with Pfizer Inc that includes speaking and lecture fees. Noriko Yanagitani reports a relationship with Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited that includes speaking and lecture fees. Noriko Yanagitani reports a relationship with Eli Lilly and Company that includes speaking and lecture fees. Noriko Yanagitani reports a relationship with AstraZeneca PLC that includes speaking and lecture fees. Noriko Yanagitani reports a relationship with Bayer Holding Co Ltd that includes speaking and lecture fees. Noriko Yanagitani reports a relationship with Chugai Pharmaceutical Co Ltd that includes paid expert testimony. All other Authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miura, K., Yamaguchi, O., Mori, K. et al. Prophylactic pegfilgrastim reduces febrile neutropenia in ramucirumab plus docetaxel after chemoimmunotherapy in advanced NSCLC: post hoc analysis from NEJ051. Sci Rep 14, 3816 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54166-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54166-x

Keywords

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.