Abstract

To identify risk factors for smoking among pregnant women, and adverse perinatal outcomes among pregnant women. A case–control study of singleton full-term pregnant women who gave birth at a university hospital in Jordan in June 2020. Pregnant women were divided into three groups according to their smoking status, active, passive, and non-smokers. They were interviewed using a semi-structured questionnaire that included demographic data, current pregnancy history, and neonatal outcomes. Low-level maternal education, unemployment, secondary antenatal care, and having a smoking husband were identified as risk factors for smoke exposure among pregnant women. The risk for cesarean section was ninefold higher in nulliparous smoking women. Women with low family income, those who did not receive information about the hazards of smoking, unemployed passive smoking women, and multiparty raised the risk of neonatal intensive care unit admission among active smoking women. This risk increased in active and passive women with lower levels of education, and inactive smoking women with low family income by 25 times compared to women with a higher level of education. Smoking is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes. Appropriate preventive strategies should address modifiable risk factors for smoking during pregnancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Smoking is associated with many adverse perinatal outcomes and could be controlled and modified by universal efforts1. Smoking is associated with congenital malformations2, fetal growth restriction3, respiratory distress4, low birth weight5, length and head circumference6,7, and premature labour8,9. While passive smoking seems to be no less detrimental as it is associated with premature labour too10,11, and gestational hypertension4.

Furthermore, an independent risk factor for fetal growth limitation is regarded to be paternal smoking12, and stillbirth irrespective of maternal smoking status13. Higher parental education and monthly family income were protective factors for preterm delivery8.

Middle Eastern nations often use tobacco, and Jordan has a high rate of smokers among pregnant mothers14,15. The overall smoking rate in Jordan is 40.90%, with a male smoking rate of 59.00% and female smoking rate of 22.80%. Jordan is sixth among world countries and first among the Middle Eastern countries in relation to smoking16.

In low- and middle-income nations, smoking is still very common, both actively and passively17,18,19. The question of risk factors for active or passive smoking among pregnant women remains controversial. Younger, less educated pregnant women are more likely to become passive smokers17,20,21, where the level of prenatal care had no significant effect22. On the other hand, some studies showed that higher level of maternal education, shift work, and unemployment were predictors for smoking during pregnancy23. Some studies suggest that low level of maternal education is a very relevant risk factor for smoking among pregnant women17,24.

The World “No Tobacco Day (WNTD) 2021 campaign” and "Commitment to quit smoking" amid the COVID-19 pandemic is supported by the Jordanian Ministry of Health (MOH, Jordan 2021). The purpose of this study was to investigate Jordanian women's risk factors for smoking and perinatal outcomes.

Study objectives

-

1.

Exploring the most common risk factors for smoking among pregnant women.

-

2.

Investigating risk factors for maternal and neonatal outcomes based on maternal smoking status.

-

3.

Examining risk factors for admission to the NICU in relation to maternal smoking status.

-

4.

Analyzing the risk factors associated with cesarean section based on maternal smoking.

Methods

Study design and setting

A prospective case–control study was conducted in June 2020 at the King Abdullah University hospital (KAUH), a tertiary referral hospital connected to the Jordan University of Science and Technology in the north of Jordan. This hospital was chosen because it is a major and large hospital in Jordan, serving a substantial number of patients in the northern region of the Kingdom. It provides services for pregnant women and outpatient clinic visits. The presence of a computerized system in the hospital and medical laboratories facilitates the conduct of the study and reaching the target sample. Additionally, there are suitable rooms available to ensure complete privacy and comfort for patients.

Target population

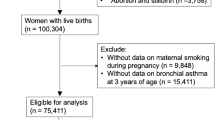

Full-term singleton pregnant women with an alive fetus, the absence of chronic medical illnesses, pregnancy difficulties, gestational hypertension, and diabetes mellitus were the inclusion criteria for the study. Participants had to agree and complete of the study questionnaire.

Data collection

Pregnant women who met the inclusion criteria participated in a face-to-face survey, and laboratory and neonatal department records were also made available. A centralized computer database was used to store and analyze the data. The 180 women who were a part of the study were all interviewed using a semi-structured questionnaire that the researchers designed depend on previous studies and it were tested and retested for validity15,25. Data were collected from women attending the hospital's gynecology clinics over a period of three months (Please see supplementary materials). Women were invited to participate in the study by a research assistant, and after approval, the form is filled out in a private room while waiting for her appointment at the women’s clinic to maintain privacy and confidentiality. The women's consent was obtained to collect samples, and they were collected in the hospital laboratory by specialists. The examination coincided with requests for regular examinations of pregnant women to monitor the pregnancy by an obstetrician and gynecologist, in accordance with the approved conditions for conducting human research. A minimum sufficient population sample, with a confidence level of 90% and a margin of error of 5%, was determined to be 176. The population was selected using a stratified sampling method. According to the smoking status, questionnaires were divided participants into three groups: Group I current active smokers, Group II of women who were passive smokers, and Group III of women who were neither current passive smokers nor active smokers.

Data collected were included; the independent study variables maternal age, education level, employment status, family income, husband smoking habits, maternal and medical history. The questioner also investigate the awareness of the impacts of smoking were. Dependent factors included perinatal and neonatal outcomes, gestational age at birth, delivery method, birth weight, length, head circumference, Apgar score at one and five minutes, and admission to neonatal intensive care unit. The questionnaire on smoking status categories as [current smoker, non-smoker, and/or expose to Second Hand Smoke (SHS)]. Evaluating smoking status (number of cigarettes smoked per day), and exposure to ambient smoke (type and duration). In addition, we used to validate self-reported smoking status using stem cotinine test. Cotinine is the best biomarker for tracking exposure among non-smokers (passive smoking). Accordingly, this indicator reflects cotinine concentrations in the blood. Active smokers always have serum cotinine levels higher than 10 nanograms per milliliter (ng/ml), while non-smokers exposed to typical levels of passive smoking have serum Concentrations less than one ng/ml. After severe exposure to passive smoking, for non-smokers serum cotinine levels can range between 1 and 10 ng/ml (CDC, 2015, 2017). Therefore, serum cotinine levels were evaluated as [levels of < 10 ng/ml, levels of 10–30 ng/ml, > 30 ng/ml]. All participants were divided into three groups according to their smoking status: group 1, current active smokers; Group 2, women who are currently exposed to passive smoking; the third group, non-smoking women, is neither active nor passive.

Ethical considerations

The University Review Committee approved this study for Research on Humans. Study participants signed informed consent after providing adequate information. Everyone who participated had the option to withdraw at any moment. All information collected was kept private and confidential. Data were collected accordance with Declaration of Helsinki26.

The study was approved by the Institutional Human Research Board (IRB) at Jordan University of Science and Technology, and King Abdullah university hospital. [22/139].

Participation was voluntary and participants could opt out at any time; Signing the consent form indicates consent to participate in the study. The consent form excluded the possibility of undue deception, undue influence or intimidation, and was only signed after potential persons had been adequately informed. Their decision to participate will not affect the doctor-patient relationship or any other benefits to which they are entitled. Personal information about the subjects will never be disclosed, and the data collected will be kept confidential. Furthermore, we can confirm that all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data analysis

The IBM SPSS 25 application program was used to conduct the statistical analysis (SPSS: An IBM Company, New York, USA). The Shapiro–Wilk W-criterion was used to assess the nature of the data distribution. In accordance with the distributional type of the feature, different statistical analysis procedures were employed. A mean value with a 95% confidence interval was used to convey quantitative data together with its central tendency and dispersion. Bivariate logistic regression analysis determined associations between pregnant women’s characteristics and adverse perinatal outcomes depending on maternal smoking status. To calculate the proportionate rate of differences between the study and control groups, odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used. If the CI for the OR included 1.0, then the differences between groups as insignificant. If values of CI were more than 1.0, then the studied trait was considered a risk factor. A p-value of 0.05 was used to define statistical significance for all two-sided statistical tests.

Results

Characteristic of the studied groups

A total of 180 pregnant women participated in the study, with 60 women in each of the active smoking, passive smoking, and non-smoking groups. Table 1 displays the characteristics of the study participants.

Risk factors for smoking among Jordanian women

The study found that smoking during pregnancy was more likely in women with low levels of maternal education, such as those who only completed secondary school. Compared to women who were employed, those without jobs smoked more frequently. Lack of regular antenatal care during pregnancy increased the risk of smoking, both active and passive. Women whose husbands were smokers had a 38-fold higher risk to be also smokers, as well as to be passive smokers. Maternal age, family monthly income, parity, and awareness about the hazards of smoking did not affect the risk for active and passive smoking among pregnant women. The details of the risk factors for smoking among participants are represented in Table 2.

Risk factors of adverse pregnancy outcomes and maternal smoking status

Nulliparous smoking women had a ninefold higher risk of having a cesarean section (CS), while non-smoking or passive smoking women did not have this risk. Low family monthly income increased the risk of CS among women of Group I, while unemployment increased it more than sixfold in women of Group II. Factors that increase the need for CS are represented in Table 3.

The current study showed that maternal age at delivery significantly increases the risk of NICU admission in all three groups of women. Multiparty raised this risk more than 10 times in Group I women, whereas in Group II nulliparity was a risk factor for NICU admission, while multiparity was a protective factor. Women who smoked, both actively and passively, and had lower levels of education were at much higher risk for NICU admission. Additionally, low family monthly income negatively affected the risk of NICU admission women of Group I. Risk factors for NICU admission are represented in Table 4.

In all groups of pregnant women, this study’s variables did not affect the rates of CS, preterm delivery, low birth weight, length, head and chest circumferences, low Apgar scores at 1st and 5th minutes, and NICU admissions.

Discussion

One of the avoidable risk factors for poor prenatal outcomes is smoking, which the world's health care systems should address1.

This study found that the strongest predictive factor for active and passive smoking among pregnant women was having a smoking husband. Paternal smoking increases the risk of maternal smoking by 38 times and second-hand smoking by 236 times. The second important risk factor was low-level maternal education, secondary school or less, which raised the chance to be a smoker by 25 times compared to women with a higher level of education. Having a bachelor’s degree or higher reduced the chances for being an active or passive smoker. These findings are supported by other studies17,21,24.

Being unemployed had more than the two-fold risk of being a smoker compared to those women who worked during pregnancy. This finding is comparable to the findings of other studies where being unemployed increased the risk of being a pregnant smoker21,23.

Additionally, this study revealed that poor antenatal care increased the risk of both active and passive smoking. This is probably due to the less responsible approach to childbirth, or due to getting less information about the dangers of smoking during pregnancy. In contrast, Garg and Mora-Pinzon found that the level of prenatal care did not affect maternal smoking status22.

Women who smoke are more likely to have a CS for non-reassuring fetal status27. However, this study found that there are additional risk factors that increase the incidence of CS in women who were active or second-hand smokers. These additional risk factors for needing a CS were nulliparity, low family income, poor antenatal care and lack of adequate knowledge about the hazards of smoking during pregnancy.

Li and colleagues27 showed that smoking significantly increases the prevalence of NICU admission27. This study found, in addition, that maternal age significantly increases the risk of NICU admission in active and passive smokers, as well as non-smoking women. Furthermore, multiparty increased the risk of NICU admission in actively smoking women, those with lower level of education, and low income. Among passive smoking women, the factor that significantly increased the rate of NICU admission was lower levels of education.

In all participant groups, other research variables had no significant effect on the probability of CS, preterm delivery, low birth weight, length, head, or chest circumferences, low Apgar score at 1 or 5 min, or NICU admission. These results are particularly supported by another study which revealed that there is no correlation between smoking status and Apgar score at 5 min6. The authors are not aware of other studies with similar methodology that aimed at identifying risk factors for adverse perinatal outcomes in relation to maternal smoking status.

This study supports the previous research that indicates that smoking among pregnant women, both passive and active, is an issue that needs the implementation of intervention for the prevention of risks associated with tobacco use14. There is still a high percentage of passive and active smoking among pregnant women in Jordan 15. In response, the Jordan Ministry of Health issued plans to combat smoking and indicated that Jordan was able to provide the capabilities for citizens to quit smoking through the implementation of the necessary programs and policies, and the opening of cessation clinics28, in concordance with the World No Tobacco Day (WNTD) 2021 campaign and "Commitment to quit smoking" amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Strengths and limitations

This study could act as a baseline for other larger studies and could help stakeholders and decision-makers to implement smoking prevention strategies. It excluded high-risk pregnant women, discussed a limited number of perinatal outcomes, and did not consider pregnancy complications such as gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, fetal abnormalities, and placental abruption, which could be related to smoking.

This study included cotinine measurement. This is not considered a "gold standard" in pregnant women, especially for passive smoking verifying20, but may give some indication of the extent of the exposure to smoke. Further research on this issue is mandated (Supplementary information).

Conclusions and recommendations

This study demonstrated that smoking during pregnancy—both active and passive—increases the rate of cesarean section (CS) and neonatal intensive care unit admission, especially in women with additional risk factors such as maternal age, nulliparity, low level of education, low family income, maternal unemployment, and lack of knowledge about the hazards of smoking during pregnancy. Furthermore, the study discovered several indicators that determine whether pregnant women may smoke actively or passively that, in addition to the risk factors for higher CS and NICU admissions, include paternal smoking status, and deficient of antenatal care. Health care workers should consider these factors during evaluation encounters.

Data availability

Data is available based on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Committee opinion no. 721 summary: Smoking cessation during pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol 130(4), 1. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002348(2017).

Raitio, A. et al. Maternal risk factors for congenital vertebral anomalies: A population-based study. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 105, 1087–1092 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and the risk of congenital urogenital malformations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Pediatrics 10, 973016 (2022).

Adibelli, D. & Kirca, N. The relationship between gestational active and passive smoking and early postpartum complications. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. 33(14), 2473–2479. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2020.1763294 (2020).

Huang, S. H. et al. The effects of maternal smoking exposure during pregnancy on postnatal outcomes: A cross-sectional study. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. JCMA 80(12), 796–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcma.2017.01.007 (2017).

Kharkova, O. A., Grjibovski, A. M., Krettek, A., Nieboer, E. & Odland, J. Ø. Effect of smoking behavior before and during pregnancy on selected birth outcomes among singleton full-term pregnancy: A Murmansk county birth registry study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14(8), 867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14080867 (2017).

Rumrich, I. et al. Effects of maternal smoking on body size and proportions at birth: a register-based cohort study of 1.4 million births. BMJ Open 10(2), e033465. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033465 (2020).

Ferguson, K. K. et al. Demographic risk factors for adverse birth outcomes in Puerto Rico in the PROTECT cohort. PLoS ONE 14(6), e0217770. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217770 (2019).

Liu, B. et al. Maternal cigarette smoking before and during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth: A dose-response analysis of 25 million mother-infant pairs. PLoS Med. 17(8), e1003158. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003158 (2020).

Hoyt, A. T. et al. Does maternal exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke during pregnancy increase the risk for preterm or small-for-gestational age birth?. Matern. Child Health J. 22(10), 1418–1429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2522-1 (2018).

Rang, N. N., Hien, T. Q., Chanh, T. Q. & Thuyen, T. K. Preterm birth and secondhand smoking during pregnancy: A case-control study from Vietnam. PLoS ONE 15(10), e0240289. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240289 (2020).

Chen, M. M., Chiu, C. H., Yuan, C. P., Liao, Y. C. & Guo, S. E. Influence of environmental tobacco smoke and air pollution on fetal growth: A prospective study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(15), 5319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155319 (2020).

Qu, Y. et al. Exposure to tobacco smoke and stillbirth: A national prospective cohort study in rural China. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 74(4), 315–320. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2019-213290 (2020).

Hamadneh, S., Kassab, M., Eaton, A., Wilkinson, A. & Creedy, D. K. Sudden unexpected infant death. In Handbook of Healthcare in the Arab World (ed. Laher, I.) (Springer, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74365-3_144-1.

Hamadneh, J., Hamadneh, S., Amarin, Z. & Al-Beitawi, S. Knowledge, attitude and smoking patterns among pregnant women: A Jordanian perspective. Ann. Glob. Health 87(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.3279 (2021).

World Population Review. Smoking Rates by Country 2021. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/smoking-rates-by-country.

Madureira, J. et al. The importance of socioeconomic position in smoking, cessation and environmental tobacco smoke exposure during pregnancy. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 15584. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72298-8 (2020).

Mahmoodabad, S., Karimiankakolaki, Z., Kazemi, A., Mohammadi, N. K. & Fallahzadeh, H. Exposure to secondhand smoke in Iranian pregnant women at home and the related factors. Tobacco Prev. Cessation 5, 7. https://doi.org/10.18332/tpc/104435 (2019).

Reece, S., Morgan, C., Parascandola, M. & Siddiqi, K. Secondhand smoke exposure during pregnancy: A cross-sectional analysis of data from Demographic and Health Survey from 30 low-income and middle-income countries. Tobacco Control 28(4), 420–426. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054288 (2019).

Hikita, N. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure among pregnant women in Mongolia. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 16426. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16643-4 (2017).

Kondracki, A. J. Prevalence and patterns of cigarette smoking before and during early and late pregnancy according to maternal characteristics: The first national data based on the 2003 birth certificate revision, United States, 2016. Reprod. Health 16(1), 142. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0807-5 (2019).

Garg, S. & Mora-Pinzon, M. C. Trends and risk factors of secondhand smoke exposure in nonsmoker pregnant women in Wisconsin, 2011–2016. WMJ 118(3), 132–134 (2019).

de Wolff, M. G. et al. Prevalence and predictors of maternal smoking before and during pregnancy in a regional Danish population: A cross-sectional study. Reprod. Health 16(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0740-7 (2019).

Härkönen, J., Lindberg, M., Karlsson, L., Karlsson, H. & Scheinin, N. M. Education is the strongest socio-economic predictor of smoking in pregnancy. Addiction 113(6), 1117–1126. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14158 (2018).

Chaaya, M., Jabbour, S., El-Roueiheb, Z. & Chemaitelly, H. (2004) Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of argileh (water pipe or hubble-bubble) and cigarette smoking among pregnant women in Lebanon. Addict. Behav. 9, 1821–1831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.04.008 (2004).

Goodyear, M. D., Krleza-Jeric, K. & Lemmens, T. The declaration of Helsinki. BMJ. 335(7621), 624–625. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39339.610000.BE (2007).

Li, R., Lodge, J., Flatley, C. & Kumar, S. The burden of adverse obstetric and perinatal outcomes from maternal smoking in an Australian cohort. Austral. New Zeal. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 59(3), 356–361. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.12849 (2019).

The Jordanian World Health Organization (2021). http://www.moh.gov.jo/DetailsPage/MOH_EN/NewsDetailsAR.aspx?ID=741. Accessed 31 May 2021.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Linköping University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H.: Writing, Analytics, J.H.: Investigation, validatoion, E.A.: Writing, Revision, R.A.: Conceptaualization, Superviosion, and A.G.H.: Reviewing, editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hamadneh, S., Hamadneh, J., Alhenawi, E. et al. Predictive factors and adverse perinatal outcomes associated with maternal smoking status. Sci Rep 14, 3436 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53813-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53813-7

Keywords

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.