Abstract

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is increasing in middle- and low-income countries, and this disease is a burden on public health systems. Notably, dietary components are crucial regulatory factors in T2DM. Plant-based dietary patterns and certain food groups, such as whole grains, legumes, nuts, vegetables, and fruits, are inversely correlated with diabetes incidence. We conducted the present study to determine the association between adherence to a plant-based diet and the risk of diabetes among adults. We conducted a cross-sectional, population-based RaNCD cohort study involving 3401 men and 3699 women. The plant-based diet index (PDI) was developed using a 118-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). Logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association between the PDI score and the risk of T2DM. A total of 7100 participants with a mean age of 45.96 ± 7.78 years were analysed. The mean PDI scores in the first, second, and third tertiles (T) were 47.13 ± 3.41, 54.44 ± 1.69, and 61.57 ± 3.24, respectively. A lower PDI was significantly correlated with a greater incidence of T2DM (T1 = 7.50%, T2 = 4.85%, T3 = 4.63%; P value < 0.001). Higher PDI scores were associated with significantly increased intakes of fibre, vegetables, fruits, olives, olive oil, legumes, soy products, tea/coffee, whole grains, nuts, vitamin E, vitamin C, and omega-6 fatty acids (P value < 0.001). After adjusting for confounding variables, the odds of having T2DM were significantly lower (by 30%) at T3 of the PDI than at T1 (OR = 0.70; 95% CI = 0.51, 0.96; P value < 0.001). Our data suggest that adhering to plant-based diets comprising whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, vegetable oils, and tea/coffee can be recommended today to reduce the risk of T2DM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a significant healthcare challenge worldwide and contributes to more than 1 million deaths annually as a primary cause of mortality 1. The global incidence of T2DM continues to increase, with more than 500 million people affected by T2DM by 20232. Implementing preventive strategies involving modifiable lifestyle factors such as diet, smoking status, stress, and physical activity contributes significantly to reducing the economic and clinical burden of T2DM 3,4. Substantial evidence supports the idea that adherence to various healthy dietary patterns, including Mediterranean-style diets, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diets, prudent patterns, and dietary guidelines, plays a crucial role in reducing susceptibility to type 2 diabetes5. A plant-based diet is characterized by the consumption of vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, seeds, and whole grains, particularly excluding certain animal products 6. Dietary patterns rich in plant-derived foods and low in animal-derived foods are associated with a lower incidence of chronic diseases, as indicated in the 2015 DGAC Scientific Report 7. Emerging evidence suggests that plant-based dietary patterns are linked to a reduced risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and dyslipidemia 8,9, gastroesophageal disease 10, cancer 11, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) 12, T2DM 6, and obesity 13,14. Moreover, a plant-based diet is likely to ameliorate common complications in diabetic patients, namely, sleep disturbances and psychological disorders15.

Epidemiologic studies have demonstrated the protective effects of certain plant-derived substances, such as polyphenols comprising flavonoid compounds, phenolic acids, stilbenes, and lignans, on insulin sensitivity to prevent T2DM by combining data from 18 cohorts16,17. Other potential strategies for the antidiabetic effect of a plant-based diet include reducing systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, enhancing the gut microbiota, and promoting weight loss 6,18. According to a recent meta-analysis of observational studies, plant-based diets are inversely associated with T2DM in high-income countries, while this correlation remains unknown in low- or middle-income countries6. Dietary patterns and composition (i.e., consumption of grains) varied between low- and high-income countries, which is why the results may not be generalizable to all races19,20.

To the best of our knowledge, in Iran, no studies have investigated the association between a plant-based diet and the risk of T2DM. In addition, the results of other aspects of research in Iran, such as CVD incidence, GDM incidence and cancer risk, are controversial 21,22,23. Therefore, in the present study, we sought to determine whether a plant-based diet can moderate the likelihood of T2DM in low- and middle-income countries to become a crucial public health priority.

Methods

Study design and participants

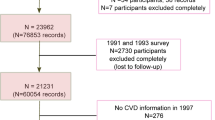

This cross-sectional study utilized data obtained from the Ravansar Non-Communicable Disease (RaNCD) cohort and was conducted with the approval of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (grant number: 92472). The RaNCD is an ongoing community-based prospective study aimed at assessing noncommunicable diseases within the Kurdish population. Comprehensive details of this study have been previously published 24. Initially, 10,047 participants were enrolled in the study during the baseline phase of the RaNCD study. Participants were excluded based on specific criteria: had an energy intake above 4200 or less than 800 kcal per day (746), had cancer (83), had a cardiovascular disease (1566), had hypertension (375), or were pregnant (138). After applying the exclusion criteria, a total of 7100 participants were included in this analysis (see Fig. 1).

General measurements

Information regarding age, sex, marital status, and smoking habits was gathered through trained interviewers and online questionnaires. Physical activity levels were assessed using the PERSIAN cohort questionnaire and categorized into three groups: low (24–36.5 MET/hour per day), moderate (36.6–44.4 MET/hour per day), and high (≥ 44.5 MET/hour per day)25,26. Socioeconomic status (SES) was determined using variables related to residence, level of literacy, and economic well-being and was classified into three groups ranging from lowest to highest levels 24.

Anthropometric data, including weight, visceral fat area (VFA), and body mass index (BMI), were obtained using an automated bioelectric impedance device (In Body Co., Seoul, Korea). Additionally, waist circumference (WC) was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm. WC was measured at the narrowest point immediately below the lowest rib and above the iliac crest 24.

Dietary assessment and plant-based diet index (PDI) calculation

A trained dietitian collected dietary data using a validated semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) consisting of 118 food items. This FFQ was utilized for the annual assessment of typical food and beverage intake.

The FFQ estimates the intake frequency (per day, week, month, and year) and quantity of each food item consumed. Food items were categorized into 18 groups based on their nutrient content, as demonstrated in Table 1. These groups were further classified into broader categories: healthy plant foods, less healthy plant foods, and animal foods. Healthy plant foods included whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, vegetable oils, tea, and coffee, while less healthy foods included fruit juices, refined grains, potatoes, sugar-sweetened beverages, and sweets/desserts.

Furthermore, animal foods consisted of animal fats, eggs, dairy products, fish/seafood, meats, and other animal-based items. Each participant received a score ranging from 1 to 5 for every food group based on their quintile of consumption.

To compute the plant-based diet index (PDI), the highest quintile within healthy plant foods and less healthy plant foods were allotted 5 points, mirroring the highest scores as similar to the lowest quintile within animal foods. Conversely, the lowest quintile of healthy plant foods and less healthy plant foods, as well as the highest quintile of animal foods, received the lowest score (1 point). The cumulative scores of all food groups were then calculated to derive the overall index scores, ranging theoretically from 18 to 90 and representing the lowest to the highest possible scores 27.

Definition of type 2 diabetes mellitus

For the diagnosis of T2DM, fasting blood sugar (FBS) levels were evaluated in accordance with the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) criteria, which consider levels equal to or greater than 126 mg/dL and/or treatment with antidiabetic medications 28.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 14.2 software (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to test the normality of the variables. Differences in continuous variables across the PDI tertiles were assessed using analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA), while categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. The means ± SDs of qualitative characteristics across the different tertiles of adherence to the PDI were calculated. All dietary intakes of participants across tertiles of plant-based diet adjusted for daily energy intake.

Logistic regression models were employed to evaluate the associations between the PDI score and T2DM incidence. Two different models were used in this analysis: (1) Model 1, adjusted for age and sex; and (2) Model 2, adjusted for age, sex, energy intake, physical activity and SES. We selected the covariates according to previous studies 29,30,31,32. A P value of < 0.05 with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was considered to indicate statistical significance in this study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (KUMS.REC.1394.318). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All the participants provided oral and written informed consent.

Results

Basic participant characteristics

Baseline information on the participants is presented across the tertiles of PDI scores in Table 2. A total of 7100 participants, with a mean age of 45.96 years, BMI of 96.43 cm, and visceral fat area of 118.07 kg, were included in the current survey. Of these participants, 47.90% were male and 52.10% were female, with 408 individuals (5.74%) diagnosed with T2DM. The mean PDI scores in the first, second, and third tertiles (T) were 47.13 ± 3.41, 54.44 ± 1.69, and 61.57 ± 3.24, respectively.

Participants with higher PDI scores tended to have a higher socioeconomic status, were more likely to be married, exhibited lower levels of physical activity, and had a reduced risk of current smoking (P < 0.001). Additionally, a significant association was observed between lower PDI scores and a greater incidence of T2DM (T1 = 7.50%, T2 = 4.85%, T3 = 4.63%; P < 0.001) (Table 2).

PDI and dietary intake

In Table 3, the mean dietary intakes of participants across different tertiles of PDI are depicted, with energy intake adjusted. Individuals in T3 of the PDI demonstrated increased consumption of nutrients and foods, including carbohydrates, trans fats, fibre, vegetables, fruits, olives, olive oil, legumes, soy products, tea/coffee, whole grains, nuts, vitamin E, vitamin C, and omega-6 (P < 0.001).

Conversely, higher adherence to the PDI was associated with lower intakes of proteins, lipids, saturated fat, seeds, dairy products, red and white meats, eggs, vitamin D, and omega-3 fatty acids (P < 0.001).

PDI and T2DM

Table 4 displays both crude and adjusted ORs (95% CI) for T2DM across the tertiles of PDI. According to the crude model, the odds of T2DM at T3 in the DPI were significantly lower than those at T1 (OR = 0.59; 95% CI = 0.46, 0.77). This significant relationship persisted even after we adjusted for potential factors such as age and sex; a 37% decrease in the odds of developing T2DM was observed in T3 patients compared to T1 patients (OR = 0.63; 95% CI = 0.48, 0.82). Further adjustment for energy intake, physical activity, and SES revealed a 30% decrease in the odds of having T2DM at T3 compared to T1 (OR = 0.70; 95% CI = 0.51, 0.96; P-trend < 0.001).

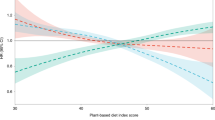

Figure 2 illustrates the association between DPI and T2DM among different sex and age groups, demonstrating inverse associations between DPI and T2DM in both sex and age categories.

Discussion

In this study, our findings revealed that participants with higher PDI scores had lower odds of having T2DM. Notably, even after adjusting for age and sex, a significant inverse association was observed between higher PDI tertiles and a reduced risk of T2DM. This robust association persisted after we adjusted for confounding variables such as age, sex, energy intake, physical activity, and SES. Furthermore, the inverse relationship between increased energy intake from plant-rich foods and T2DM was consistent across sex and various age groups.

Prior research has extensively explored the interconnection between plant-based diets and susceptibility to T2DM. In line with our current study, Satija et al. conducted a prospective cohort study involving 200,727 individuals in the U.S. Their investigation revealed an independent association between plant-based diets, particularly high-quality plant foods, and a remarkable 49% reduction in the risk of T2DM, even after adjusting for BMI and other diabetes risk factors 27. Similarly, Ahmed et al. conducted a four-year prospective study involving 35,307 Swedish men and women. Their findings highlighted an elevated risk of T2DM among individuals with inadequate vegetable intake. Specifically, after accounting for BMI, age, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and physical activity, a 62% increased risk of T2DM was observed in men (OR = 1.62; 95% CI = 1.00, 2.63) 33. Multiple studies exploring different populations have consistently demonstrated an inverse relationship between adherence to plant-based diets and the risk of T2DM. In a cross-sectional study involving 50,694 Chinese participants, a significant association was observed between the fourth quartile of PDI and a reduced risk of T2DM (OR = 0.83; 95% CI = 0.75–0.92)34. Likewise, the Singapore Chinese Health Study indicated that adherence to plant-based diets and higher PDI scores correlated with a notable 17% reduction in the risk of T2DM35. Moreover, findings from the 7.3-year Rotterdam Study, conducted on Dutch adults by Chen et al., reported a 13% reduced risk of T2DM among individuals with higher PDI scores, even after adjusting for lifestyle confounders 36. Further affirming these observations, three large cohort studies conducted in the U.S. involving both men and women over a 4-year follow-up period highlighted a substantial link between better adherence to a plant-based diet and a decreased risk of T2D. Specifically, these studies reported a 12–23% increase in the risk of developing diabetes over four years among participants who exhibited the greatest decline in PDI adherence 37. Overall, the Henan Rural Cohort Study conducted by Yang et al. among Chinese adults revealed a notable association between a higher plant-based diet score and a reduced risk of T2DM (OR = 0.88; 95% CI: 0.79–0.98). This study highlighted a 4% decrease in the risk of developing T2DM with a one standard deviation increase in the PDI 38. However, it is important to note that not all studies have demonstrated a consistent relationship between T2DM incidence and PDI. For instance, the findings of two cohort studies contradicted the outcomes observed in the present study and suggested no significant relationship between T2DM incidence and PDI 39,40. These discrepancies might arise due to variations in populations, dietary behaviors, and lifestyles.

One such example is the study by Kim et al. in Korea, where they observed that the healthy plant-based diet index (hPDI), rather than the traditional PDI, was associated with the risk of developing T2DM. This study emphasized that in a population consuming more plant foods and fewer animal foods, solely increasing the quantity of plant foods might not be effective. However, the consumption of higher-quality plant foods has been shown to be inversely related to the risk of developing diabetes 40. These divergent outcomes across different populations underscore the impact of dietary habits and lifestyles on the study results. It is worth noting that the current study on Kurdish ethnicity in Iran represents the initial exploration of the relationship between the PDI and the risk of T2DM within this specific ethnic group, potentially providing unique insights into this association.

The outcomes of our study align with those of Kim et al., who demonstrated that individuals with higher mean PDI scores tend to exhibit increased daily intake of whole grains, fruits, vegetables, legumes, tea, and coffee. Conversely, they also tend to consume lower amounts of dairy, eggs, and meat. This similarity in dietary patterns strengthens the observations across different populations, highlighting the consistency of these associations between plant-based diets and specific food intake choices. 40. Indeed, the findings from our study align with prior research indicating the advantages of a plant-based diet in preventing diabetes. A cohort study conducted in China revealed that increased consumption of fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes and limited intake of red meat were associated with a reduced risk of T2DM 31.

Similarly, Lv et al. highlighted that adhering to a dietary pattern rich in fruits and vegetables while restricting red meat intake led to a substantial 26% reduction in the risk of developing T2DM 32. These consistent outcomes across diverse studies underscore the potential benefits of specific dietary choices in mitigating the risk of diabetes 41.

According to the Stockholm Diabetes Prevention Program, a clear inverse relationship was observed between high intake of fruits and vegetables and a decreased risk of T2DM42. Schwingshack et al. further supported this by demonstrating that increased consumption of fruits and vegetables correlates with a decreased incidence of T2DM43. Additionally, a prospective study among healthy females highlighted that higher intake of leafy green vegetables and fruits was associated with a decreased risk of developing T2DM 44. Meta-analyses also consistently underscored the risk reduction in T2DM among individuals consuming fruits, vegetables, soy products, and whole grains, contrasting with the increased risk linked to higher red meat consumption43,45. These collective findings emphasize the pivotal role of specific dietary patterns in lowering the risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Certainly, the protective effect of a plant-based diet (PDI) against T2DM risk might involve various biological pathways. As phytochemicals are predominantly found in plant-based foods46, diets abundant in fruits and vegetables are strongly associated with a reduced risk of T2DM 47. A meta-analysis involving 18,164 patients with T2DM demonstrated that the overall intake of dietary flavonoids is linked to a decreased risk of developing T2DM 48. Additionally, another meta-analysis encompassing seven cohort studies revealed that individuals with higher flavonoid intake had an 11% lower likelihood of developing T2DM than did those with minimal flavonoid intake49. These findings underscore the potential role of phytochemicals and flavonoids present in plant-based foods in mitigating the risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Certainly, the mechanisms underlying the potential benefits of a plant-based diet against T2DM encompass various aspects. The phytochemicals present in these diets exhibit antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, aiding in safeguarding pancreatic beta-cells from hyperglycemia and oxidative stress. Moreover, they support enhanced glucose absorption via insulin-dependent pathways, thereby improving insulin sensitivity and potentially preventing insulin resistance50,51. These compounds also have an impact on energy balance and regulate lipid and carbohydrate metabolism. Additionally, a plant-based diet is associated with improved intestinal microbiome health, increased dietary fibre content, and increased levels of unsaturated fatty acids, as well as decreased levels of saturated fatty acids, cholesterol, and animal protein37. For instance, an Umbrella Review analysing sixteen meta-analyses highlighted the significant association between higher fibre intake and a reduction in the relative risk of type 2 diabetes, fasting blood sugar concentration, and glycosylated hemoglobin levels among individuals with type 2 diabetes52. These factors collectively contribute to the potential protective effect of plant-based diets against the development and management of type 2 diabetes.

These findings are consistent with the proposed mechanisms. We observed a significant decrease in the number of individuals diagnosed with T2DM and a lower percentage of individuals consuming antidiabetic drugs as adherence to a plant-based diet increased. Additionally, our analysis revealed a decreasing trend in fasting blood sugar (FBS) levels with increasing plant-based diet index (PDI) tertiles. These results align with previous research by Lotfi et al., who demonstrated an inverse relationship between FBS concentration and greater adherence to a plant-based diet (OR = 0.42; 0.33–0.53)53. These findings reinforce the potential benefits of a plant-based diet in managing and possibly preventing type 2 diabetes, as indicated by the correlations observed in our study and in prior research.

The present study has several strengths, including a large sample size, adjustment for a wide range of potential confounders and the use of a validated questionnaire administered by trained specialists. However, there are limitations to consider. The cross-sectional study design prevented the establishment of causal relationships between the plant-based diet index (PDI) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) incidence. Additionally, while the Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ), employed for determining PDI validity and reliability for evaluating plant foods, was used, it may not have captured the full dietary spectrum accurately. Despite controlling for various confounding factors, some potential confounders might not have been entirely accounted for in the study 54.

Conclusion

Taken together, the findings of this study suggest that increased adherence to a plant-based diet comprising whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, vegetable oils, and tea/coffee could lower the risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). However, further research is essential to validate and strengthen these results. This study underscores the importance of considering such dietary patterns to potentially mitigate the risk of T2DM, but additional investigations would be valuable to confirm and expand upon these findings.

Data availability

The data sets generated during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request via email.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CVDs:

-

Cardiovascular diseases

- DASH:

-

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension

- FBS:

-

Fasting blood sugar

- FFQ:

-

Food Frequency Questionnaire

- GDM:

-

Gestational diabetes mellitus

- hPDI:

-

Healthy plant-based diet index

- IDF:

-

International Diabetes Federation

- PDI:

-

Plant-based diet index

- RaNCD:

-

Ravansar Non-Communicable Disease

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

- T:

-

Tertiles

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- VFA:

-

Visceral fat area

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

References

Khan, M. A. B. et al. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes—Global burden of disease and forecasted trends. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 10(1), 107 (2020).

Atlas D. International diabetes federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 7th edn (International Diabetes Federation, 2015) 33.

Aguiar, E. J., Morgan, P. J., Collins, C. E., Plotnikoff, R. C. & Callister, R. Efficacy of interventions that include diet, aerobic and resistance training components for type 2 diabetes prevention: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 11(1), 1–10 (2014).

Ajala, O., English, P. & Pinkney, J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of different dietary approaches to the management of type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 97(3), 505–516 (2013).

Ley, S. H., Hamdy, O., Mohan, V. & Hu, F. B. Prevention and management of type 2 diabetes: dietary components and nutritional strategies. The Lancet. 383(9933), 1999–2007 (2014).

Qian, F., Liu, G., Hu, F. B., Bhupathiraju, S. N. & Sun, Q. Association between plant-based dietary patterns and risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 179(10), 1335–1344 (2019).

McGuire, S. Scientific report of the 2015 dietary guidelines advisory committee. Washington, DC: Us departments of agriculture and health and human services, 2015. Adv. Nutr. 7(1), 202–204 (2016).

Satija, A. et al. Healthful and unhealthful plant-based diets and the risk of coronary heart disease in US adults. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 70(4), 411–422 (2017).

Trautwein, E. A. & McKay, S. The role of specific components of a plant-based diet in management of dyslipidemia and the impact on cardiovascular risk. Nutrients 12(9), 2671 (2020).

Heidarzadeh-Esfahani, N. et al. Dietary intake in relation to the risk of reflux disease: A systematic review. Prevent. Nutr. Food Sci. 26(4), 367 (2021).

Loeb, S. et al. Association of plant-based diet index with prostate cancer risk. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 115(3), 662–670 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. Prepregnancy plant-based diets and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: A prospective cohort study of 14,926 women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 114(6), 1997–2005 (2021).

Greger, M. A whole food plant-based diet is effective for weight loss: The evidence. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 14(5), 500–510 (2020).

Siqueira, C. H. I. A., Esteves, L. G. & Duarte, C. K. Plant-based diet index score is not associated with body composition: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Res. 104, 128–139 (2022).

Daneshzad, E. et al. Association of dietary acid load and plant-based diet index with sleep, stress, anxiety and depression in diabetic women. Br. J. Nutr. 123(8), 901–912 (2020).

Rienks, J., Barbaresko, J., Oluwagbemigun, K., Schmid, M. & Nöthlings, U. Polyphenol exposure and risk of type 2 diabetes: Dose–response meta-analyses and systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 108(1), 49–61 (2018).

Da Porto, A. et al. Polyphenols rich diets and risk of type 2 diabetes. Nutrients. 13(5), 1445 (2021).

McMacken, M. & Shah, S. A plant-based diet for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. JGC 14(5), 342 (2017).

Ghanbari-Gohari, F., Mousavi, S. M. & Esmaillzadeh, A. Consumption of whole grains and risk of type 2 diabetes: A comprehensive systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Food Sci. Nutr. 10(6), 1950–1960 (2022).

Hopping, B. N. et al. Dietary fiber, magnesium, and glycemic load alter risk of type 2 diabetes in a multiethnic cohort in Hawaii. J. Nutr. 140(1), 68–74 (2010).

Shirzadi, Z., Daneshzad, E., Dorosty, A., Surkan, P. J. & Azadbakht, L. Associations of plant-based dietary patterns with cardiovascular risk factors in women. J. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Res. 14(1), 1 (2022).

Rigi, S., Mousavi, S. M., Benisi-Kohansal, S., Azadbakht, L. & Esmaillzadeh, A. The association between plant-based dietary patterns and risk of breast cancer: A case–control study. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 3391 (2021).

Zamani, B. et al. Association of a plant-based dietary pattern in relation to gestational diabetes mellitus. Nutr. Dietetics 76(5), 589–596 (2019).

Pasdar, Y. et al. Cohort profile: Ravansar Non-Communicable Disease cohort study: The first cohort study in a Kurdish population. Int. J. Epidemiol. 48(3), 682–683 (2019).

Poustchi, H. et al. Prospective epidemiological research studies in Iran (the PERSIAN Cohort Study): Rationale, objectives, and design. Am. J. Epidemiol. 187(4), 647–655 (2018).

Jetté, M., Sidney, K. & Blümchen, G. Metabolic equivalents (METS) in exercise testing, exercise prescription, and evaluation of functional capacity. Clin. Cardiol. 13(8), 555–565 (1990).

Satija, A. et al. Plant-based dietary patterns and incidence of type 2 diabetes in US men and women: Results from three prospective cohort studies. PLoS Med. 13(6), e1002039 (2016).

Saeedi, P. et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 157, 107843 (2019).

Kautzky-Willer, A., Harreiter, J. & Pacini, G. Sex and gender differences in risk, pathophysiology and complications of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocr. Rev. 37(3), 278–316 (2016).

Hillier, T. A. & Pedula, K. L. Characteristics of an adult population with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: The relation of obesity and age of onset. Diabetes Care. 24(9), 1522–1527 (2001).

Gill, J. M. & Cooper, A. R. Physical activity and prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Sports Med. 38, 807–824 (2008).

Agardh, E., Allebeck, P., Hallqvist, J., Moradi, T. & Sidorchuk, A. Type 2 diabetes incidence and socio-economic position: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 40(3), 804–818 (2011).

Ahmed, A., Lager, A., Fredlund, P. & Elinder, L. S. Consumption of fruit and vegetables and the risk of type 2 diabetes: A 4-year longitudinal study among Swedish adults. J. Nutr. Sci. 9, e14 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Meng, Y. & Wang, J. Higher adherence to plant-based diet lowers type 2 diabetes risk among high and non-high cardiovascular risk populations: A cross-sectional study in Shanxi, China. Nutrients. 15(3), 786 (2023).

Chen, G.-C. et al. Diet quality indices and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: The Singapore Chinese Health Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 187(12), 2651–2661 (2018).

Chen, Z. et al. Plant versus animal based diets and insulin resistance, prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: The Rotterdam Study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 33, 883–893 (2018).

Chen, Z. et al. Changes in plant-based diet indices and subsequent risk of type 2 diabetes in women and men: Three US prospective cohorts. Diabetes Care. 44(3), 663–671 (2021).

Yang, X. et al. Association of plant-based diet and type 2 diabetes mellitus in Chinese rural adults: The Henan Rural Cohort Study. J. Diabetes Investig. 12(9), 1569–1576 (2021).

Flores, A. C. et al. Prospective study of plant-based dietary patterns and diabetes in Puerto Rican adults. J. Nutr. 151(12), 3795–3800 (2021).

Kim, J. & Giovannucci, E. Healthful plant-based diet and incidence of type 2 diabetes in Asian population. Nutrients. 14(15), 3078 (2022).

Lv, J. et al. Adherence to a healthy lifestyle and the risk of type 2 diabetes in Chinese adults. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46(5), 1410–1420 (2017).

Barouti, A. A., Tynelius, P., Lager, A. & Björklund, A. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: Results from a 20-year long prospective cohort study in Swedish men and women. Eur. J. Nutr. 61(6), 3175–3187 (2022).

Schwingshackl, L. et al. Food groups and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 32, 363–375 (2017).

Bazzano, L. A., Li, T. Y., Joshipura, K. J. & Hu, F. B. Intake of fruit, vegetables, and fruit juices and risk of diabetes in women. Diabetes Care. 31(7), 1311–1317 (2008).

Li, W., Ruan, W., Peng, Y. & Wang, D. Soy and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 137, 190–199 (2018).

Delshad Aghdam, S. et al. Dietary phytochemical index associated with cardiovascular risk factor in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 21(1), 293 (2021).

Cooper, A. J. et al. The association between a biomarker score for fruit and vegetable intake and incident type 2 diabetes: The EPIC-Norfolk study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 69(4), 449–454 (2015).

Liu, Y.-J. et al. Dietary flavonoids intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Clin. Nutr. 33(1), 59–63 (2014).

Xu, H., Luo, J., Huang, J. & Wen, Q. Flavonoids intake and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Medicine. 97(19), e0686 (2018).

Abshirini, M. et al. Higher intake of phytochemical-rich foods is inversely related to prediabetes: A case–control study. Int. J. Prevent. Med. 9, 64 (2018).

Bahadoran, Z., Mirmiran, P., Tohidi, M. & Azizi, F. Dietary phytochemical index and the risk of insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction: A prospective approach in Tehran lipid and glucose study. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 66(8), 950–955 (2015).

McRae, M. P. Dietary fiber intake and type 2 diabetes mellitus: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. J. Chiropract. Med. 17(1), 44–53 (2018).

Lotfi, M. et al. Plant-based diets could ameliorate the risk factors of cardiovascular diseases in adults with chronic diseases. Food Sci. Nutr. 11(3), 1297–1308 (2023).

Mohammadifard, N. et al. Validation of a simplified food frequency questionnaire for the assessment of dietary habits in Iranian adults: Isfahan Healthy Heart Program, Iran. ARYA Atheroscler. 11(2), 139 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the PERSIAN cohort study collaborators and Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. The Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education has also contributed to the funding used in the PERSIAN Cohort through Grant No. 700/534.

Funding

This research was supported by Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (Grant No. 92472).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.H.E. and Y.P. designed the study. M.D. and F.N. conducted the data analyses, and N.H.E., E.S., D.S. and M.M. interpreted the results. N.H.E., F.K.H. and M.D. drafted the manuscript, and all the authors revised it critically for important intellectual content and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heidarzadeh-Esfahani, N., Darbandi, M., Khamoushi, F. et al. Association of plant-based dietary patterns with the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus using cross-sectional results from RaNCD cohort. Sci Rep 14, 3814 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52946-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52946-z

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.