Abstract

This study aimed to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the emergency department (ED) visits of cardiovascular disease (CVD) patients. The customized data of the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) from 2017 to 2020 were analyzed. CVD patients were defined by the code ‘V192’ based on the NHIS coverage benefit expansion policy. The number of ED visits of CVD patients, as well as executed procedures in 2020 (during the pandemic), were compared to the corresponding average numbers in 2018 and 2019 (prepandemic). Stratification by age group, residential area and hospital location was performed. The number of ED visits of newly diagnosed CVD patients decreased by 2.1% nationwide in 2020 (2018–2019: 97,041; 2020: 95,038) and decreased the most (by 14.1%) in March (2018–2019: 8539; 2020: 7334). However, the number of executed procedures increased by 1.1% nationwide in 2020 (2018–2019: 74,696; 2020: 75,520), while it decreased by 11.9% in April (2018–2019: 6603; 2020: 5819). The most notable decreases in the number of newly diagnosed CVD patients (31.7%) and procedures (29.2%) in March 2020 were observed in the Daegu·Gyeongbuk area. CVD patients living in the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic may experience difficulty accessing healthcare facilities and receiving proper treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared a global pandemic of COVID-19 since it quickly spread worldwide starting in Wuhan, China, in December 20191. The first confirmed case of COVID-19 in Korea was reported on January 20, 20202. To control the transmission of COVID-19, the Korean government and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDCP) implemented different levels of measures, such as social distancing or the redistribution of health care delivery systems. They provided guidelines to install exothermic detectors and to conduct simple health status questionnaires to screen suspected COVID-19 patients with fever or cough at the hospital entrance under social distancing circumstances3,4,5. Furthermore, they ordered the securing of designated hospitals or isolation beds for COVID-19 patients, and the hospitals started to triage COVID-19 patients. The government expanded the range of assignment of COVID-19 designated hospitals from 42 on February 21, 2020, to 69 on March 10, 20206. The hospitals also rearranged areas to distinguish COVID-19 patients based on symptom assessment and triaged following the selective process protocol. For example, the hospitals assigned some emergency department (ED) units: a unit for screening patients and awaiting COVID-19 test results and an acute care unit divided into 3 degrees of severity (normal beds, negative-pressure emergency intensive care rooms, extremely intensive isolation rooms)5. The adjusted hospital systems restricted the accessibility of health care services for patients with other diseases who had not been infected with COVID-19, who were considered to experience collateral damage from the COVID-19 pandemic7. Collateral damage is also said to be the effect of distraction, including unintended disruption to health care delivery or collapse on the management of critical emergencies8.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) patients have experienced collateral damage from the COVID-19 pandemic. Since most health care systems required these patients to be screened for COVID-19 and wait to be triaged or allocated a negative-pressure room for isolation, they could not access the health care system or receive proper care during the pandemic. An international survey conducted within 909 inpatient and outpatient centers from 108 countries showed a significant decline in CVD diagnostic tests or procedures, such as transthoracic echocardiography, by 42% from March 2019 to March 2020 and decreased further by 64% from March 2019 to April 20209. A decrease in the number of CVD patients who admitted in EDs was observed in Saarland, Germany. The number of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients, including those with unstable angina pectoris, myocardial infarction with ST-elevation (STEMI), and myocardial infarction without ST-elevation (NSTEMI), decreased by 41% after the first COVID-19 case in calendar week 10 of 2020 compared to the same period in 2019 and decreased by 48% during the shutdown in weeks 12–16 of 202010. These examples of collateral damage due to the COVID-19 pandemic still leave concerns regarding underdiagnosed harmful but treatable CVDs related to a reduction in ED visits.

In this study, we aimed to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the emergency department visits of patients with a new diagnosis of CVD to address the potential collateral damage of the pandemic in Korea.

Methods

Ethics statement

The study was exempt from IRB review by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University College of Medicine/Seoul National University (IRB No. E-2010–002-1160), and written informed consent was waived because all analyses were performed by using secondary data for which personal information is unidentifiable.

Study materials

A retrospective analysis of a cohort of patients from 2017 to 2020 was performed using the Customized Data of the National Health Information Database (NHID). The NHID is a public database based on the unidentifiable personal information of over 50 million people with the utilization of health care provided by the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS)11. The NHIS data include sociodemographic information, medical utilization data from clinics or pharmacies, death status, and the results of national health screening programs. The diagnosis of diseases and the types of medical services are presented as International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th revision (ICD-10) codes12 and Korean Standard Classification of Diseases and Causes of Death (KCD-8) codes13.

Study population

The eligible individuals were CVD patients who newly visited the ED and were diagnosed with the relevant diseases in 2018, 2019, and 2020. The CVD patients were defined by the code ‘V192’, granted if the patients had been charged for medical care benefits for CVDs and hospitalized to receive treatment for the diseases within 30 days based on the NHIS coverage benefit expansion policy. Each defined disease and procedure was based on the KCD-8 code as follows (Supplementary Table S1). CVD patients who newly visited the ED were those with no history of ED visits for the relevant diseases in the previous year. Of the total CVD patients who visited the ED from 2017 to 2020 (Supplementary Table S2), CVD patients who newly visited the ED between 2018 and 2020 were identified (Tables 1 and 2). The patients’ ED visits were identified by the code indicating ‘emergency department visit.’ The number of CVD patients who underwent the related procedures was also examined.

Analyses

The age group was divided into 3 categories: under 40, from 40 to 64, and older than 65 years. The insurance type was divided into 3 types: self-employed insured, employee-insured, and medical-aid beneficiary. The insurance premium was categorized into 5 groups: medical aid, the bottom 25%, the bottom 50%, the top 50%, and the top 25%. The regions were categorized into 5 categories: the Capital (Seoul, Incheon, Gyeonggi), Central (Daejeon, Sejong, Gangwon, Chungbuk, Chungnam), North of the Southeastern (Daegu, Gyeongbuk), South of the Southeastern (Busan, Ulsan, Gyeongnam) and Southwestern (Gwangju, Jeonbuk, Jeonnam, Jeju) regions.

The reference period was from 2018 to 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic. The pattern of the number of daily newly confirmed COVID-19 cases in Korea in 2020 was observed by using data from the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA)14. The average number of patients who newly visited the ED and those who underwent the related procedures from 2018 and 2019 for each month were compared to the corresponding number in 2020. The percentage difference was also obtained by dividing the difference in the number between two periods. Stratified analyses by age group, residential area, and location of the medical institution were conducted. In addition, the concordance between residential areas and the location of the hospital visited by the CVD patients was calculated to reflect the effect of proper response on emergent CVD patients.

All analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

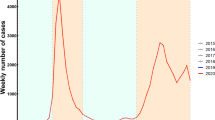

Pattern of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020

In 2020, there were three waves of COVID-19 in Korea (Fig. 1). The first COVID-19 epidemic wave struck the Daegu·Gyeongbuk region in March 2020, leading to the introduction of the first intensive social distancing measures nationwide in April2. The second wave was centered in the capital region in August 20202. The third wave started in the capital and central regions and spread nationwide in December 20202.

Comparison of basic characteristics

We compared the basic characteristics of the CVD patients, including sex, age, insurance type, insurance premium, residential areas, and the location of the medical institution, from 2018 to 2020. The total number of CVD patients who visited the ED during the study period was 108,841 in 2018, 114,579 in 2019 and 111,500 in 2020 (Supplementary Table S2). Among these patients, 94,627 newly visited the ED in 2018, 99,454 newly visited in 2019 and 95,038 newly visited in 2020 (Table 1). The proportions of sex, age, insurance type, income level, residential area, and location of the medical institution remained similar over the 3 years. During the observed years, the proportion of males (66.8–68.3%) and those aged older than 65 years (54.1–55.8%) was higher than their counterparts.

The number of visits to emergency department

The total number of CVD patients who were newly diagnosed and visited the ED decreased by 2.1% nationwide in 2020 compared to the corresponding average numbers in 2018 and 2019 (2018–9: 97,041; 2020: 95,038) (Table 2). The decrease was observed to be the most significant at 14.1% nationwide in March 2020 (2018–9: 8539; 2020: 7334), while it increased the most by 11.6% in June 2020 (2018–9: 7514; 2020: 8388). Comparing the stratified age groups, the group aged older than 65 years showed the sharpest decrease in March 2020 by 16.0% (2018–9: 4750; 2020: 4049), and the group aged 40 to 64 years had the sharpest decrease by 13.1% in April 2020 (2018–9: 3378; 2020: 2967), followed by that of 11.6% in March 2020.

The total number of new CVD patients with ED visits decreased in all regions except for the southwestern region (Table 2). The sharpest decline of 31.6% was observed in the Daegu·Gyeongbuk area in March 2020 (2018–9: 950; 2020: 649) and in the capital region in April 2020 by 11.9% (2018–9: 3828; 2020: 3371) (Fig. 2). Similar patterns were observed regarding the location of the medical institutions, with a decline by 31.7% in the Daegu·Gyeongbuk area in March 2020 (2018–9: 812; 2020: 555) and 13.6% in the capital region in April 2020 (2018–9: 4520; 2020: 3907). The concordance between the residential area and the location of the medical institutions decreased in all regions except for the southwestern region (6.0%), with the sharpest decrease by 6.3% in the central region. Likewise, the Daegu·Gyeongbuk area showed a 29.0% decrease in March 2020 (2018–9: 761; 2020: 540) and a decrease of 11.3% in the capital region in April 2020 (2018–9: 3712; 2020: 3292). The differences in the number of new CVD patients with ED visits based on the other characteristics, including sex, insurance type and income level, are shown in Supplementary Table S3.

The number of emergency department visits and undergone procedures

While the total number of CVD patients with new diagnoses and ED visits decreased nationwide in 2020, that of those who had undergone procedures showed an increase of 1.1% in 2020 (2018–9: 74,696; 2020: 75,520) (Table 3). In April 2020, the sharpest decline of 11.9% was observed. Among the age groups, the number of individuals aged older than 65 years decreased the most by 12.1% in April 2020, as did the number of individuals aged between 40 and 64 years (12.2%). The capital region and the southwestern region showed an increase in the total number; however, that of the central region and Daegu·Gyeongbuk decreased. The most significant reduction was observed in Daegu·Gyeongbuk in March 2020. The changes based on the other characteristics, including sex, insurance type and income level, are shown in Supplementary Table S4.

Discussion

The total number of CVD patients with new diagnoses and ED visits decreased. In particular, the Daegu·Gyeongbuk area experienced the most significant decline in March 2020. This indicates that the Daegu·Gyeongbuk region experienced the most severe collateral damage from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The onset of the early COVID-19 epidemic in Korea appeared as a pattern of sporadic clusters. The Daegu·Gyeongbuk region was confronted with the crisis of the first epidemic wave caused by a religious group, Shincheonji, in the middle of February 2020. With the soaring number of confirmed cases in the Daegu·Gyeongbuk region in March 2020, intensive social distancing was applied nationwide until the beginning of May. Then, the second wave appeared similar to the first with religious activities and rallies in the capital region in August. The third wave started in December with spreading nationwide through the various clusters of hospitals and religious facilities, and even family-to-family infections occurred2. Our findings demonstrate that dramatic declines during the pandemic were observed in accordance with the epidemic periods, when the first and second epidemic waves struck, followed by a surge in COVID-19 cases nationwide. It also emphasizes that the regions with COVID-19 clusters were affected more severely; for example, there were immense pressures on the health care delivery system in Daegu after 121 health care workers were infected with the COVID-19 virus5.

Surveys conducted in the United States demonstrated that older people tended to be more compliant with social distancing regulations, and younger people had greater concern about COVID-19 infection or being quarantined15,16. This can explain the results of our study, which showed a relatively low decline in ED visits among cardiovascular patients older than 65 years, while those among patients under 40 years old decreased by more than 10%. Given the small number of young age groups in our study, it was reported from a multicenter study with five different major children’s hospitals in Korea that the number of pediatric ED visits during the COVID-19 pandemic was 58.1% lower than that in the previous years of 2018 and 201917. However, the difference in age groups should be interpreted cautiously due to the larger number of patients in the older age groups than in the younger age groups. Age is an important risk factor for CVD18; therefore, an underlying tolerance and vulnerability to cardiovascular disease among the older age groups may explain our findings of a small decrease in the number of ED visits and the procedures observed in our study.

Many countries have introduced a variety of measures to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 virus, such as Korea, which has implemented many kinds of restrictions and rules, including social distancing measures. Even a few European countries imposed nonpharmaceutical interventions, such as lockdowns, where there was a high incidence rate of COVID-1919. In previous studies from China, Spain, Italy, Germany, and the United States, negative effects of national lockdowns on ED visits and emergency care in patients with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases were observed, with a reduction of 40–70% in ED admissions and proper procedures for STEMI and strokes9,10,19,20,21. These results are consistent with our findings. However, in the case of Finland, even though the total number of ED visits decreased by 16% after the lockdown, the visit rate due to acute myocardial infarctions or cerebral strokes remained stable during the study period22. The changed government policies altered the circumstances of hospitals, and the hospitals tried to adapt their stances to these policies.

Not only were the systems of hospitals adjusted, but the patients also changed their attitudes regarding visiting the hospitals, even the EDs. Some patients who were not infected with the COVID-19 virus but had other diseases were reluctant to visit the hospitals because of the fear of transmission7. Outpatients in India were hesitant about regular physician visits and delayed or avoided unneeded visits due to higher caution of contracting COVID-1923. This phenomenon was caused by the past issue of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in Korea in 2015. There were intrahospital transmissions from patient to patient in EDs or hospitals and interhospital transmissions from hospital to hospital due to the transfer of confirmed patients24,25.

Ironically, the number of overall ED visits and executed procedures increased the most in June 2020. This was when the aggregation of confirmed cases was low, with a daily average of 39.3 cases, and social distancing was converted to the degree of daily life2. A previous study reported that when comparing the monthly cancer screening rates in 2019 and 2020, the figure increased in June compared to March 202026. Unlike cancer screening, it is extremely difficult to delay ED visits or endure sickness without urgent action due to the characteristics of CVD itself, well known as being time-sensitive. Therefore, it is hard to interpret whether patients were merely putting off or suspending ED visits for CVDs. Rather, it would be better to interpret it as the occurrence of a sequential increase provoked by the complications of severe patients or long-COVID sequelae of the confirmed patients during the first epidemic wave. The fact that COVID-19 may contribute to symptoms related to CVDs, such as myocardial infarction or thrombosis, has been revealed27,28. This might further lead to the possible explanation for the observed overall increase in the treatments of CVD patients.

The southwestern region showed an exceptional increase in the number of overall ED visits and executed procedures compared to the Daegu·Gyeongbuk and central regions. In 2020, the southwestern region was affected less severely than the Daegu·Gyeongbuk region (Supplementary Table S5)2,29. It is possible that the collateral damage induced by measures imposed on the system of EDs (e.g., triage) and emotional avoidance related to hospital visits might be less in the southwestern region.

The current study has some limitations to be noted with caution. First, we used the customized NHID data, including information only from 2017 up to 2020. Therefore, we could not observe the longer prepandemic period before 2017 and reflect the latest trends in this study. Second, we could not conduct an analysis of ED visits according to specific types of CVDs, such as ACS, heart failure, and arrhythmia. The code ‘V192’, which we used to define CVD patients, only includes specific CVDs with high medical expenses, as shown in Supplementary Table S1. Nevertheless, the use of the code ‘V192’ helped to increase the validity of CVD diagnosis when using claim data. This specific code is not easily assigned compared to diagnosis codes, which may include the differential diagnosis; therefore, we believe that it is more likely that CVD patients who truly need acute care were detected in this analysis. Third, we could not investigate symptom-based causes of the CVD patients’ ED visits, including chest pain, dyspnea, and syncope. The NHID provides the history of ED visits but does not have information on the detailed reasons. Lastly, there was a lack of information regarding the severity of CVDs in the NHID. Instead, we observed it based on the CVD-specific deaths reported by the Korean Statistical Information Service29. While the overall age-standardized mortality (ASMR) decreased in 2020 compared to 2018–2019 regardless of the regions, Daegu·Gyeongbuk still exhibited the greatest increase of 11.3 per 100,000 population in the crude mortality rate and the smallest decrease of 2.4 in the ASMR (Supplementary Table S6). Although the mortality statistics were presented for the general population, it could be interpreted that the severity of CVDs remained higher in the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, to the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to document the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the emergency department visits of newly diagnosed CVD cpatients to stress the likely collateral damage caused by the pandemic in Korea. We discovered a decrease in the number of CVD patients with new ED visits and emergent procedures by month, age, and region. This result indicated that collateral damage occurred as postponed responses to acute CVDs. Additionally, it calls for the importance of preparation against an unexpected pandemic. From the public health perspective, our study provides essential evidence to arrange systems and policies to deliver proper health care services within an appropriate time during the pandemic era. Further research is needed to investigate the growing burden of mortality and the other consequences of collateral damage in patients with cardiovascular or even cerebrovascular diseases in Korea during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the number of CVD patients with new ED visits in Korea was affected in 2020 compared to the prepandemic period. The overall number of CVD patients with new ED visits decreased, whereas the number of those with executed treatments increased. However, this trend differed by region and month, following the surge of COVID-19 clusters. The Daegu·Gyeongbuk area had the greatest reduction in the number of new ED visits and treatments in March throughout 2020. This indicates that CVD patients living in the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic may experience difficulty accessing health care facilities and receiving proper treatment. Future studies are required to examine the growing burden of mortality as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data availability

The customized datasets used and analyzed for the study were downloaded from the National Health Insurance Service (https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr/bd/ab/bdaba021eng.do) and available during a permitted period after the approval by the NHIS for a fee.

References

Cucinotta, D. & Vanelli, M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 91, 157–160 (2020).

Kim, Y. et al. COVID-19 1-year outbreak report as of January 19, 2021 in the Republic of Korea. Public Health Wkly. Rep. 14, 472–481 (2021).

Dighe, A. et al. Response to COVID-19 in South Korea and implications for lifting stringent interventions. BMC Med. 18, 321 (2020).

Central Defense Response Headquarters. Coronavirus Infection Prevention and Control in Hospital-Level Medical Institutions (Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, 2020). https://ncov.kdca.go.kr/shBoardView.do?brdId=2&brdGubun=24&ncvContSeq=1277.

Kang, J. et al. South Korea’s responses to stop the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Infect. Control. 48, 1080–1086 (2020).

Ministry of Health and Welfare. Financial Support of KRW 39 Billion for 69 COVID-19 Designated Hospitals. https://www.mohw.go.kr/react/al/sal0301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=04&MENU_ID=0403&CONT_SEQ=353539&page=1 (2020).

Mira, J. J. & Lorenzo, S. Collateral damage for failing to do in the times of COVID-19. J. Healthc. Qual. Res. 36, 125–127 (2021).

Pothiawala, S. COVID-19 and its danger of distraction. Qatar Med. J. 2020, 17 (2020).

Einstein, A. J. et al. International impact of COVID-19 on the diagnosis of heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 77, 173–185 (2021).

Schwarz, V. et al. Decline of emergency admissions for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events after the outbreak of COVID-19. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 109, 1500–1506 (2020).

Seong, S. C. et al. Data resource profile: The national health information database of the national health insurance service in South Korea. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 799–800 (2017).

World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision. https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en (2022).

Korea Informative Classification of Disease. Korean Standard Classification of Diseases and Causes of Death (KCD-8). https://www.koicd.kr/kcd/kcds.do (2022).

Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Latest Updates of Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19): Cases in Korea. https://ncov.kdca.go.kr (2023).

Moore, R. C., Lee, A. Y., Hancock, J. T., Halley, M. C. & Linos, E. Age-related differences in experiences with social distancing at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic: A computational and content analytic investigation of natural language from a social media survey. JMIR Hum. Factors 8, e26043. https://doi.org/10.2196/26043 (2021).

Bruine de Bruin, W. Age Differences in COVID-19 risk perceptions and mental health: Evidence from a national U.S. survey conducted in March 2020. J. Gerontol. B 76, e24–e29. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa074 (2021).

Choi, D. H. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on trends in emergency department utilization in children: A multicenter retrospective observational study in Seoul metropolitan area, Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e44 (2021).

Rodgers, J. L. et al. Cardiovascular risks associated with gender and aging. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 6, 19 (2019).

Thu, T. P. B., Ngoc, P. N. H., Hai, N. M. & Tuan, L. A. Effect of the social distancing measures on the spread of COVID-19 in 10 highly infected countries. Sci. Total Environ. 742, 140430 (2020).

Kulkarni, P., Mahadevappa, M. & Alluri, S. COVID-19 pandemic and the impact on the cardiovascular disease patient care. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 16, 173–177 (2020).

Adjemian, J. et al. Update: COVID-19 pandemic-associated changes in emergency department visits—United States, December 2020–January 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 70, 552–556 (2021).

Kuitunen, I. et al. The effect of national lockdown due to COVID-19 on emergency department visits. Scand. J. Trauma. Resusc. Emerg. Med. 28, 114 (2020).

Oliver, S. & Melvin, C. L. J. Out-patient attitude towards hospitals during COVID-19 in India. Stud. Appl. Econ. https://doi.org/10.25115/eea.v40iS1.5497 (2022).

Ki, H. K., Han, S. K., Son, J. S. & Park, S. O. Risk of transmission via medical employees and importance of routine infection-prevention policy in a nosocomial outbreak of middle east respiratory syndrome (MERS): A descriptive analysis from a tertiary care hospital in South Korea. BMC Pulm. Med. 19, 190 (2019).

Ki, M. MERS outbreak in Korea: Hospital to hospital transmission. Epidemiol. Health 37, e2015033. https://doi.org/10.4178/epih/e2015033 (2015).

Park, H. et al. The impact of COVID-19 on screening for colorectal, gastric, breast, and cervical cancer in Korea. Epidemiol. Health 44, e2022053. https://doi.org/10.4178/epih.e2022053 (2022).

Tedeschi, D., Rizzi, A., Biscaglia, S. & Tumscitz, C. Acute myocardial infarction and large coronary thrombosis in a patient with COVID-19. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 97, 272–277 (2021).

Luo, H. et al. Age differences in clinical features and outcomes in patients with COVID-19, Jiangsu, China: A retrospective, multicentre cohort study. BMJ Open 10, e039887. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039887 (2020).

Korean Statistical Information Service. Korean Statistical Information Service (KOSIS). https://kosis.kr/eng/ (2023).

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project from the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI). This study was funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HC20C0005). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.S., J.Y.B., S.H.S., S.C., J.-B.P., B.K., S.H.Y.; Data curation: J.Y.B, S.H.S. Formal analysis: A.S., J.Y.B, S.H.S., S.C.; Funding acquisition: A.S.; Investigation: A.S., J.Y.B, S.H.S.; Methodology: A.S., J.Y.B, S.H.S, S.C.; Validation: A.S., J.Y.B, S.H.S., S.C., J.-B.P., B.K., S.H.Y.; Visualization: A.S., J.Y.B.; Writing—original draft: A.S., J.Y.B, S.H.S.; Writing—review & editing: A.S., J.Y.B, S.H.S., S.C., J.-B.P., B.K., S.H.Y.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baek, J.Y., Seo, S.H., Cho, S. et al. Emergency department visits of newly diagnosed cardiovascular disease patients in Korea during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Rep 14, 397 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50709-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50709-w

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.