Abstract

An inverse social gradient in early childhood overweight has been consistently described in high-income countries; however, less is known about the role of migration status. We studied the social patterning of overweight in preschool children according to the mother’s socio-economic and migration background. For 9250 children of the French ELFE birth cohort with body mass index collected at age 3.5 years, we used nested logistic regression to investigate the association of overweight status in children with maternal educational level, occupation, household income and migration status. Overall, 8.3% (95%CI [7.7–9.0]) of children were classified as overweight. The odds of overweight was increased for children from immigrant mothers (OR 2.22 [95% CI 1.75–2.78]) and descendants of immigrant mothers (OR 1.35 [1.04–2.78]) versus non-immigrant mothers. The highest odds of overweight was also observed in children whose mothers had low education, were unemployed or students, or were from households in the lowest income quintile. Our findings confirm that socio-economic disadvantage and migration status are risk factors for childhood overweight. However, the social patterning of overweight did not apply uniformly to all variables. These new and comprehensive insights should inform future public health interventions aimed at tackling social inequalities in childhood overweight.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The high prevalence of overweight and obesity, estimated at 17.9% in European children aged 2 to 7 years1 and its social patterning2 are a major public health issue. Several studies have identified an inverse social gradient of childhood overweight in high-income countries; children from families with low socioeconomic position (SEP) seem more affected. Excess weight is associated with many harmful comorbidities in children, both physical and mental (e.g. hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and psychological distress)3 and increases the risk of obesity in adulthood, thus contributing to social inequalities in health throughout life4.

Factors contributing to excess weight are multifaceted, involving a complex interplay between genetic predisposition and environmental5, social and behavioral determinants, which operate at different levels6. One of these determinants is children’s or family SEP, which is commonly characterized by various indicators in the literature, such as parents’ educational level, occupation, or household income. Although correlated, these indicators are all important to be considered because they capture not–inter-changeable dimensions of SEP7. For example, parents’ educational level is indicative of their knowledge and, to some extent, their health literacy and skills; parents’ occupational category provides insight into the social environment in which the child is raised; and household income reflects the family’s purchasing capacity and ability to access goods and services7. Of note, maternal education was found the strongest predictor of child overweight, which can be attributed in part to the temporal consistency of maternal educational level, in contrast to the variability of occupation and income8. A study of 11 European cohorts showed that as early as preschool, children whose mothers had a lower degree of education were more likely to be overweight than those whose mothers had a higher educational degree. Still, parental occupation and household income were also found associated with child overweight and should deserve equal attention9. The few studies that focus on these multiple indicators usually do not cautiously address their interrelation, especially when introducing them all at once in multi-adjusted models, which impairs the interpretation of the results. Davison et al.10 recommended ordering the various determinants of childhood overweight according to their proximity to the outcome, under a socio-ecological conceptual framework. Accordingly, we hypothesized that educational level would be an upstream factor, followed by occupational category, which would in turn influence income.

Beyond these common socio-economic factors, the socio-cultural determinants of child overweight have been under-studied and are worth considering for addressing the issue of inequalities more comprehensively. In particular, people with an immigration background are disproportionally affected by overweight and obesity11,12,13. To date, European data on the health of immigrants and their descendants remain partial and results are inconsistent14. According to the “healthy migrant effect”, individuals who are able to migrate have a better health status on average than their non-migrating counterparts, both in their country of birth and in the host country15. However, the health status for ethnic/racial minorities deteriorates once they have settled in the host country. This deterioration increases over time, mainly due to poor working and housing conditions, downward social mobility, and difficulties in accessing care5,16, along with an acculturation process, which can affect individuals’ health behaviours. In this context and as suggested by Jusot et al.17, migration status may be at the most distal position in our conceptual framework, upstream of the other SEP indicators.

This study investigated the early social patterning of overweight in preschool children while accounting for both mothers’ SEP and migration status in the ELFE national birth cohort.

Material and methods

Study population

The ELFE study is a nationwide, multidisciplinary birth cohort18. It recruited 18,329 children born in a random sample of 344 maternity units located in metropolitan France over 25 days in four different periods in 2011. Inclusion criteria were single or twin births ≥ 33 weeks of amenorrhea and mothers ≥ 18 years old and not planning to leave Mainland France within 3 years. To ensure the inclusion of women with limited French literacy, the information letter and consent form were translated into Arabic, Turkish, and English, the three most commonly spoken languages in France in non-French speakers. Among the eligible mothers, 51% agreed to participate in the study and provided informed and written consent for their and their child’s participation. Fathers gave signed consent for the child’s participation when present at inclusion or were informed about their rights to oppose it. The ELFE study received approvals from the Advisory Committee for the Processing of Information for Health Research (Comité Consultatif sur le Traitement des Informations pour la Recherche en Santé) and National Data Protection Authority (Commission National Informatique et Libertés) and the National Council for Statistical Information. All research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data collection and measurements

Data collection included a comprehensive set of information on maternal and paternal characteristics, pregnancy, birth, and postnatal outcomes as well as follow-up data on the child’s health, development, and environment.

Data collection methods included a face-to-face interview conducted by trained investigators at the maternity hospital and computer-assisted telephone interviews conducted by a survey institute at the 2-month, 2-year and 3.5-year follow-ups. In addition, information from the medical record, including the mother’s health history and the child’s anthropometric measurements and health status at birth, was collected at the maternity hospital. Information on the mother’s SEP and migration history was collected during the 2-month follow-up.

During the telephone follow-up interview at 3.5 years, parents were asked to report their child’s weight and height from the health booklet. From these, the body mass index (BMI) was calculated for each child (weight [kg]/[height (m)]2), as was overweight (including obesity) defined using the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF)19 age- and sex-specific reference (BMI ≥ IOTF-25 cut-off).

Maternal migration status was defined in three categories: “non-immigrant” for women born French to two French parents (in or outside of France); “descendant of immigrant” for women born in France to at least one non-French parent; and “immigrant” for women born outside France, and without French nationality at birth. Additionally, the maternal country of birth was used as a descriptive variable to further characterize the migration dimension. The variable was classified as follows: France, European Union (except France), Turkey and North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, and other (other Africa, Eastern Europe, Asia, America).

Three indicators of SEP were defined in categories as follows: maternal educational level (≤ high school level, 1–2 years university degree, and ≥ 3-year university degree); maternal occupation (“executive and top management”, “middle occupation [teacher, nurse, technician, foreman]”, “farmer and skilled blue-collar worker”, “clerk”, “manual worker, unemployed and student “); and household income level per consumption unit, categorized into quintiles. According to the definition provided by the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies, the latter indicator is calculated by allocating distinct weights to each member of a household, depending on the member’s age (1 consumption unit for the householder, 0.5 for other household members aged 14 or over, and 0.3 for each child aged less than 14 years). This enables the comparison of living standards across households with varying sizes and compositions20.

The adjustment variables considered for this study included child sex, maternal age at delivery (in years), and parity (first-time mother, second-time mother or multiparous).

Study sample selected for statistical analyses

For twin births, the study inclusion was limited to one twin chosen randomly (Fig. 1). Measurements were selected from an age range of 2.5 to 4.2 years, with a mean child age of 3.5 years. Only children with at least one BMI measure available within this age range were eligible for analysis (N = 9250). When multiple BMI measures were available for the same child, only the last one was used.

Statistical analyses

We first estimated the prevalence of children’s overweight at 3.5 years, before and after accounting for the study design and non-response at inclusion and at follow-up, using specific weighting. This weighting method included calibration on margins from the state register’s statistical data as well as data from the 2010 French National Perinatal study21 for the following variables: sex, region, parity, marital status, mother’s and father’s age, mother’s education, mother’s migration status, mother’s and father’s employment at the time of delivery, child-birth preparation sessions, mother living in a partnership at birth, and alcohol consumption during pregnancy. This approach complies with the procedures recommended by the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies.

The associations of overweight status in children aged 3.5 years with maternal migration status and SEP indicators (maternal educational level, maternal occupational category and household income) were first assessed using weighted chi-squared tests. These migration and SEP indicators were structured from the most distal to the most proximal within a four–nested-variable framework, derived from both socio-ecological10 and hierarchical approaches22. As stated in the introduction, we assumed that migration status and educational level were at the most distal levels, with the latter influencing occupational category, which in turn would impact income level, as the most proximal variable7. Accordingly, model 1 included maternal migration status. Models 2, 3 and 4 successively added maternal educational level, maternal occupational category and household income (Fig. 2). This hierarchical approach was intended to ensure that intermediate SEP variables did not affect the association of the more distal migration and SEP indicators with the outcome under study (i.e., overweight status). Consequently, the results for each variable are interpreted as they are added to the model. Unweighted logistic regression models were used to assess the odds of child overweight according to variations in migration or SEP modalities, estimating odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All four models were adjusted for child sex, maternal age at delivery and parity. Missing values were imputed using the missForest R package, which uses random forest imputation techniques. The random forest approach, introduced by Breiman in 200123, is a highly effective method for both classification and regression. By combining multiple randomized decision trees and averaging their predictions, this algorithm has demonstrated very good performance24. Furthermore, to ascertain the necessity of stratification, we tested for interactions between maternal migration status and each SEP variable by using an alpha risk threshold of 0.05.

Primary multivariable analyses were conducted with imputation of missing values for parity, maternal migration status, maternal educational level and household income. Sensitivity analyses were conducted for complete cases (n = 8524).

All statistical analyses involved using RStudio (2022) (RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA).

Results

Of the 9250 children included in the study, 9.8% and 8.5% were born to mothers who were descendants of immigrants or immigrants, respectively (Table 1). Most mothers (90.3%) were born in France, whereas those born outside of France were mainly from North Africa and Turkey (3.3%) and Sub-Saharan Africa (2.4%). Overall, 43.5% of mothers had ≥ 3-year university education and 32.5% had ≤ high school education; 43.5% were employed and the median monthly household income was €1619 (IQR 1238–2048) per consumption unit.

Differences between individuals included in and excluded from the study are reported in Supplementary Table 1. Mothers excluded from the sample were more often single as compared with those included. As compared with excluded mothers, included mothers were more often descendants of immigrants or immigrant themselves; more frequently had ≤ high school education; more often belonged to the clerk or manual worker or unemployed and student occupational categories; and had a lower median household income.

Of 9250 children included, 653 were classified as overweight: 7.1% (95% CI 6.5–7.6) before data weighting and 8.3% (7.7–9.0) after weighting (Table 1). The prevalence of overweight differed by regions, with the highest in Hauts-de-France (north) (10.8%) and the lowest in Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes (middle east) (5.1%; weighted prevalence) (Fig. 3).

Weighted prevalence of overweight status in children aged 3.5 years from the ELFE cohort according to metropolitan France regions (n = 9238 children). *To ensure the validity of this regional prevalence analysis, we excluded children from the Corsica region (n = 12) because of insufficient sample size. **The map was generated on R version 4.2.1 (2022-06-23) using the sf package (v1.0.12) with shapefile downloaded from https://www.data.gouv.fr/en/datasets/contours-des-regions-francaises-sur-openstreetmap.

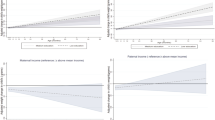

We found a social gradient in overweight for both migration and SEP (Fig. 4). The subgroups of children the most affected by excess weight were those born to immigrant mothers (weighted prevalence:14.4% [95% CI 11.7–17.6]), mothers with ≤ high school education (10.0% [8.8–11.4]); and mothers who were manual workers, unemployed, or students (15.7% [12.4–19.7]); and children living in households in the lowest income quintile (quintile 1) (11.6% [9.7–13.9]). For this final variable, the prevalence of overweight was intermediate for children from households in income quintile 2 and 3 (8.0% [95% CI 6.5–9.7] and 8.1% [6.6–9.8]). Given that we found no interaction between migration status and SEP ((p > 0.2), we did not stratify the analyses afterward.

Weighted prevalence (95% CI) of overweight status according to maternal migration status and socioeconomic position indicators for children aged 3.5 years in the ELFE national cohort. (A) Maternal migration status (n = 8998); (B) maternal education level (n = 8928); (C) maternal occupational status (n = 9250); (D) quintiles of household income per consumption unit (n = 8727).

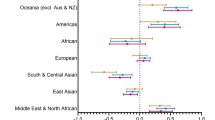

In the multivariable models, the odds of overweight status differed by migration status and was inversely associated with all three dimensions of SEP (Table 2): the odds of overweight was increased for children whose mothers were immigrants or descendants of immigrants (OR 2.22 [95% CI 1.75–2.78] and 1.35 [1.04–1.74]) versus non-immigrant mothers; mothers with ≤ high school education or 2-year university degree (1.72 [1.42–2.08] and 1.36 [1.09–1.70]) versus ≥ 3-year university degree; and mothers in the manual worker, unemployed and student category or clerk category (2.54 [1.74–3.70] and 1.35 [1.02–1.78]) versus the executive and top management category. Regarding household income, the odds of overweight was increased for children in the lowest quintile (1.39 [1.02–1.91]) than the highest quintile.

Discussion

This study confirms a social gradient of overweight in children according to the mother’s educational level. However, the gradient was not as clear for maternal occupation and household income, given that it was rather a threshold effect contrasting the lowest SEP categories to the others, namely, “manual worker, unemployed and student” for occupation and the lowest quintile of income. Additionally, the mother’s migration status seemed to play an important role, without interacting with other SEP variables. We believe our analysis adds value to the existing literature by taking a holistic approach because it incorporates the perspective of migration history, thus better disentangling the multifaceted socio-cultural determinants contributing to this health condition.

The overall prevalence of overweight in our sample (8.3%, obesity included) was relatively low as compared with national estimates reported in three other studies. The INCA3 surveys, conducted in 2014 in metropolitan France and using IOTF cut-offs, estimated a prevalence of 13.7% in children 4 to 6 years old25. Notably, children participating in the ELFE cohort study were younger than these children, precisely 3.5 years old in 2014. Likewise, a nationwide representative school survey conducted in 2013 reported an overweight rate in kindergarten (mean age 5 years) of 11.9% (90% CI 11.5–12.5)26; these latter figures apply to all regions of France, including the overseas departments (except Mayotte), where the prevalence is much higher27. Both studies share a cross-sectional design, which could explain the difference in prevalence with the ELFE cohort, more likely to be affected by selection and attrition biases (as is the case in most cohorts) that can only partly be corrected by weighting. Nevertheless, our findings are consistent with the inverse socio-economic gradient reported from pre-school age in these two other national studies, whether the definition of SEP was based on the highest occupational category among the two parents26 or the educational level of the respondent parent in INCA325. The latter study found no association with respondent occupational status. Although the territorial divide of childhood overweight has not yet been described in France, in adults, the Obepi survey reported a downward North–South gradient of obesity28. Here, we show that the geographical distribution is slightly different in early childhood, with the Northern, Southern and Western regions most affected.

The overall inverse socio-economic gradient of overweight observed in the 3.5-year-old children of the ELFE cohort did not apply uniformly to all SEP dimensions. Our findings show that for household income levels, children in the lowest quintile but not the intermediate ones were more likely to have overweight than those in the highest income quintile. Likewise, children born to “workers, unemployed and student” mothers only were more likely to have overweight than children born to mothers in the reference occupational category. This lack of clear gradient for occupational status can be partly explained by some categories being quite heterogenous, especially “farmer and skilled blue-collar worker” and “manual worker, unemployed, student,” but we could not maintain a finer granularity because of the sample size. More generally, occupation-based indicators are most often non-hierarchical29. Still, all SEP indicators, although interdependent, reflect different facets of the SEP and are not equally stable over time. For instance, income is known to be more volatile, and external shocks can temporarily impact income levels without necessarily altering household conditions. Furthermore, in our study, although a continuous gradient seems to apply to maternal education, the effects of income and occupation seem to be subject to a threshold beyond which they are no longer associated with child overweight. These two different paradigms30 have implications for interventions aimed at reducing health inequalities in terms of components and sub-population groups to be targeted in priority30. They can influence the adoption of proportionate universalism, a perspective that seeks to provide universal access to health services and interventions while directing resources to those who are most in need: this approach recognises that everyone should have access to the same level of basic care but acknowledges that some individuals and communities require additional support to achieve optimal health outcomes30,31,32.

Furthermore, our results show that the association between maternal education and child overweight was substantially attenuated after adjusting for household income. This observation suggests that the effect of maternal education on child overweight in the ELFE cohort is partly explained by household income, as was further confirmed by a mediation analysis (results not shown, but available on request). However, there is some remaining direct effect of education, as confirmed by other studies7,33,34: for example Van Rossem et al.33 reported a persistent but attenuated association between maternal educational level and child overweight after adjusting for material hardship in the Dutch Generation R cohort.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to investigate the association between maternal migration status and childhood overweight in France. The results are consistent with a systematic review of 19 studies conducted in six European countries (not France) published from 1999 to 2009 that overall found a higher risk of overweight and obesity in immigrant children than their non-immigrant counterparts11. However, most of these studies did not control for socio-economic factors in their analyses and the definition used to classify a child as an “immigrant” was not consistent across all studies. Other research from the Generation R study showed that children whose parents were born abroad were more likely to be overweight at age 4 years than children whose parents were both born in The Netherlands. However, after adjusting for maternal education, parental BMI, and infant weight change, the associations were attenuated, with the strongest attenuation observed after adjustment for maternal education33.

The “healthy migrant effect” describes migrants having better health outcomes than non-migrants in both their source and host countries. Evidence for the healthy migrant effect is inconsistent across regions and contexts. Previous studies15,35 have documented the healthy migrant effect in Canada, the United States, Australia and the United Kingdom for the prevalence of chronic conditions, self-assessed health, and obesity, but the situation in other European countries is complex and heterogeneous. Moullan et al.14 found evidence of a healthy migrant effect for self-assessed health in Italy and Spain but not Belgium and France. Some other studies have reported poorer health status among immigrants than non-immigrants in terms of chronic conditions and self-perceived health in France16,17,36 and Europe37. Differences between countries can be explained by factors such as the country of origin, the host country’s legal framework for immigration, the length of stay, and the healthcare system; the healthy migrant effect also depends on the reasons for migration15. Whether this effect extends to the offspring of immigrant mothers with regard to obesity remains unclear. A US study did not find any “healthy foreign-born effect” for childhood obesity38.

A recent study based on the ELFE cohort showed that immigrant parents’ pre-migration education had a positive impact on their children’s birth outcomes including birth weight39, but this advantage declined with length of residence in the new country. The acculturation process, which refers to the change and adaptation that occurs when individuals or groups encounter a different culture, may partly account for why this benefit diminishes with length of residence. This process entails changes in attitudes, values, beliefs, behaviors and language and can take place at both individual and group levels. A systematic review concluded that acculturation was associated with obesity in adult immigrants from low/middle-income to high-income countries40. Another Swedish study found that children of immigrants had greater risk of low physical activity and overweight than children of Swedish parents, despite a better-quality diet15. However, acculturation is a complex and nuanced phenomenon that requires careful examination41. Another study of ELFE data found that the diet of immigrant mothers was better than that of descendants of immigrants, who in turn had a better diet than non-immigrant mothers42. Therefore, women who were less acculturated had both a healthier and less processed diet than non-immigrant mothers43. However, this relationship must be tested in children to determine the extent to which it applies to them. In light of the literature42,44, we were expecting a more pronounced socio-economic gradient of childhood overweight in the non-immigrant than immigrant population, which was not confirmed given the lack of interaction between migration status and all three SEP indicators.

In the present analysis, the association between maternal migration status and childhood overweight persisted even after adjusting for other SEP variables. This finding suggests that migration status has a direct effect, independent of SEP. In particular, socio-cultural norms, values and representations could be involved. For example, perception of weight and overweight may differ according to the migration status and induce less favorable energy balance-related behaviors, regardless of SEP: a British study found that parental perceptions of healthy body size and concerns about overweight in childhood varied by ethnicity45. Disparities observed between different racial and ethnic groups could also indicate discrimination at an institutional or structural level, shaped by personal experiences, or a combination of both7. However, we cannot rule out the possibility of residual confounding due to other unmeasured dimensions of SEP. For instance, a study34 of the ELFE cohort used a multidimensional approach to measure child poverty, combining income and deprivation measures. Income poverty did not perfectly overlap with deprivation: some low-income children were not considered poor and some higher-income children were considered deprived.

There are a number of limitations to our study. As mentioned before, the prevalence estimates reported in this cohort are lower than those from other cross-sectional studies. The specific weights provided by the ELFE team to adjust the sample and mitigate these selection and attrition biases were deemed effective but not sufficient to correct the selection bias due to attrition. However, our primary objective was not to measure the prevalence itself but rather to comprehend the social patterning of childhood overweight with a holistic approach, accounting for various social determinants, in particular migration. Still, the associations under study with the SEP and migration indicators may have been stronger with a better representation of the most socially disadvantaged families. Of note, the ELFE cohort does not include children from the overseas departments. A study published in 2012 on children aged 5 to 9 years in Guadeloupe, Martinique, French Guiana and French Polynesia reported an overweight prevalence of 15.2%, 25.0%, 16.8% and 31.6%, respectively27. Hence, this exclusion could potentially bias the results by underestimating the absolute prevalence and the prevalence in the non-immigrant population. In addition, several studies have reported ethnic variations in body composition46,47,48. For the purpose of consistency, we decided to use the most commonly accepted definition of overweight: BMI greater than or equal to the IOTF-25 cut-off. However, by extension, this choice may slightly overestimate the real prevalence of overweight among some ethnic minorities7.

Our study also has notable strengths. The use of a hierarchical approach in the design of our conceptual model avoids a wrong interpretation of over-adjustment commonly encountered in other studies that incorporate all variables simultaneously in the same models. In addition to confirming that “one size does not fit all”7, our approach demonstrated both social gradient and threshold effects. Finally, the use of multiple imputation techniques mitigated potential bias introduced by missing data, which provided a significant advantage.

This study demonstrates the existence of social inequalities in the ELFE birth cohort. These findings, based on SEP and migration status, agree with those of other studies conducted in similar European cohorts11, such as Generation R33. However, more nuanced aspects of vulnerability34 need to be examined to gain a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms that structure and mediate the effect of these factors on child overweight. This examination would enable the development of concrete solutions to be applied in public health interventions. Nonetheless, if the latter have the overarching goal to reduce social inequalities in childhood overweight, their design requires an appropriate balance between individual versus structural components. Indeed, a systematic review revealed that interventions across different socio-economic groups differed in efficacy49. Those that relied on information provision for individual behavior modification were ineffective in participants with lower SEP. Only community or policy interventions aimed at bringing structural changes to the environment were successful for them. This is also corroborated by a recent systematic review which highlighted that increasing the availability of healthier food options enhanced the likelihood of healthy choices and reduced the energy content of the diet similarly among individuals with higher and lower SEP50. There are existing examples of this type of intervention that have demonstrated positive outcomes in encouraging healthier choices among consumers51. Hence, policies that increase the availability of healthier food could have potential as equitable strategies to reduce obesity and improve population health. In addition to availability, accessibility is a crucial factor in food choices. Research suggests a significant positive effect of higher occupational social class on food expenditure, which in turn influences the healthiness of food purchases52. Within the framework of proportionate universalism, only such structural interventions can empower the segment of the population facing social adversity and promote social equity in health initiatives. Another recent systematic review found that interventions delivered by lay agents among ethnic/racial minorities had some effect on lifestyle behaviors and obesity risk; additional factors for creating more effective, pragmatic, inclusive, and non-judgmental programs were to engage stakeholders, including users, in their development and adhering to theoretical frameworks53.

Conclusion

We confirmed the presence of social inequalities in childhood overweight in the ELFE cohort, appearing as early as 3.5 years. Mother’s migration status was a risk factor for child overweight, even after accounting for several SEP dimensions. Although our study corroborates the existence of a social gradient of overweight in children based on maternal educational level, this gradient was less evident for maternal occupation and household income, which indicates a threshold effect. Hence, some populations are more vulnerable than others, in particular children of mothers who are immigrants or immigrant descendants, those who are manual workers or unemployed, or with low income. Therefore, these factors should be considered for better social equity when designing obesity prevention interventions.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study is not publicly available due to ethical restrictions related to protection of participant confidentiality and legal restrictions imposed by the French National Commission on Data Processing and Liberties (CNIL). Investigators who wish to access the data reported in this article must address a reasonable request to the Elfe’s data access committee (CADE) at contact@elfe-france.fr.

Change history

06 February 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53416-2

References

Garrido-Miguel, M. et al. Prevalence and trends of Overweight and obesity in European children from 1999 to 2016: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 173(10), e192430. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.2430 (2019).

Hemmingsson, E., Nowicka, P., Ulijaszek, S. & Sørensen, T. I. A. The social origins of obesity within and across generations. Obes. Rev. 24(1), 13514. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13514 (2023).

Kluge, H. H. P. WHO European Regional Obesity Report 2022.

Singh, A. S., Mulder, C., Twisk, J. W. R., Van Mechelen, W. & Chinapaw, M. J. M. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: A systematic review of the literature. Obes. Rev. 9(5), 474–488. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00475.x (2008).

Yang, Y. C. et al. Life-course trajectories of body mass index from adolescence to old age: Racial and educational disparities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118(17), e2020167118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2020167118 (2021).

Pillas, D. et al. Social inequalities in early childhood health and development: A European-wide systematic review. Pediatr. Res. https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2014.122 (2014).

Braveman, P. A. et al. Socioeconomic status in health research: One size does not fit all. JAMA 294(22), 2879. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.22.2879 (2005).

Shrewsbury, V. & Wardle, J. Socioeconomic status and adiposity in childhood: A systematic review of cross-sectional studies 1990–2005. Obesity 16(2), 275–284. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2007.35 (2008).

Knai, C., Lobstein, T., Darmon, N., Rutter, H. & McKee, M. Socioeconomic patterning of childhood overweight status in Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 9(4), 1472–1489. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9041472 (2012).

Davison, K. & Birch, L. Childhood overweight: A contextual model and recommendations for future research. NIH Public Access 2(3), 159–171 (2001).

Labree, L. J. W., van de Mheen, H., Rutten, F. F. H. & Foets, M. Differences in overweight and obesity among children from migrant and native origin: a systematic review of the European literature: Differences in overweight and obesity among children. Obes. Rev. 12(5), e535–e547. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00839.x (2011).

Strugnell, C., Mathrani, S., Sollars, L., Swinburn, B. & Copley, V. Variation in the socioeconomic gradient of obesity by ethnicity: England’s National Child Measurement Programme. Obesity 28(10), 1951–1963. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22970 (2020).

Lu, Y., Pearce, A. & Li, L. Distinct patterns of socio-economic disparities in child-to-adolescent BMI trajectories across UK ethnic groups: A prospective longitudinal study. Pediatr. Obes. 15(4), 12598. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12598 (2020).

Moullan, Y. & Jusot, F. Why is the “healthy immigrant effect” different between European countries?. Eur. J. Public Health 24(suppl 1), 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cku112 (2014).

Kennedy, S., Kidd, M. P., McDonald, J. T. & Biddle, N. The healthy immigrant effect: Patterns and evidence from four countries. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 16(2), 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-014-0340-x (2015).

Berchet, C., Jusot, F. & Paris-dauphine, U. État de Santé et Recours aux Soins des Immigrés : Une synthèse des Travaux Français (2012).

Jusot, F., Silva, J., Dourgnon, P. & Sermet, C. Inégalités de santé liées à l’immigration en France: Effet des conditions de vie ou sélection à la migration ?. Rev. Écon. 60(2), 385–411. https://doi.org/10.3917/reco.602.0385 (2009).

Charles, M. A. et al. Cohort Profile: The French national cohort of children (ELFE): Birth to 5 years. Int. J. Epidemiol. 49(2), 368–369. https://doi.org/10.1093/IJE/DYZ227 (2019).

Cole, T. J. & Lobstein, T. Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr. Obes. 7(4), 284–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00064.x (2012).

National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies. Definition: Consumption Unit. Accessed October 16, 2023. https://www.insee.fr/fr/metadonnees/definition/c1802.

Blondel, B., Lelong, N., Kermarrec, M. & Goffinet, F. Trends in perinatal health in France from 1995 to 2010. Results from the French National Perinatal Surveys. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Biol. Reprod. 41(4), e1–e15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgyn.2012.04.014 (2012).

Victora, C. G., Huttly, S. R., Fuchs, S. C., Teresa, M. & Olinto, A. The role of conceptual frameworks in epidemiological analysis: A hierarchical approach. Int. J. Epidemiol. 26, 224–227 (1997).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Lang. 45(1), 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010933404324 (2001).

Shah, A. D., Bartlett, J. W., Carpenter, J., Nicholas, O. & Hemingway, H. Comparison of random forest and parametric imputation models for imputing missing data using MICE: A CALIBER study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 179(6), 764–774. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt312 (2014).

Anses. Étude Individuelle Nationale Des Consommations Alimentaires 3 (INCA 3) (2017).

Chardon, O. et al. La santé des élèves de grande section de maternelle en 2013: Des inégalités sociales dès le plus jeune âge. Etudes Résultats 920, 6 (2015).

Daigre, J. L. et al. The prevalence of overweight and obesity, and distribution of waist circumference, in adults and children in the French Overseas Territories: The PODIUM survey. Diabetes Metab. 38(5), 404–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2012.03.008 (2012).

Fontbonne, A. et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in France: The 2020 Obepi-Roche Study by the “Ligue Contre l’Obésité”. J. Clin. Med. 12(3), 925. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12030925 (2023).

Galobardes, B., Lynch, J. & Smith, G. D. Measuring socioeconomic position in health research. Br. Med. Bull. 81–82, 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldm001 (2007).

Arcaya, M. C., Arcaya, A. L. & Subramanian, S. V. Inequalities in health: Definitions, concepts, and theories. Glob. Health Action 8(1), 27106. https://doi.org/10.3402/GHA.V8.27106 (2015).

Affeltranger, B., Potvin, L., Ferron, C., Vandewalle, H. & Vallée, A. Theoretical and practical challenges of proportionate universalism: A review. Rev Panam Salud PublicaPan Am. J. Public Health 45, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2021.102 (2021).

Francis-Oliviero, F., Cambon, L., Wittwer, J., Marmot, M. & Alla, F. Theoretical and practical challenges of proportionate universalism: A review. Rev Panam Salud Pública 44, 1. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2020.110 (2020).

Van Rossem, L. et al. The role of early life factors in the development of ethnic differences in growth and overweight in preschool children: A prospective birth cohort. BMC Public Health 14(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-722 (2014).

Castillo Rico, B., Leturcq, M. & Panico, L. La pauvreté des enfants à la naissance en France. Résultats de l’enquête Elfe. Rev. Polit. Soc. Fam. 131(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.3406/caf.2019.3342 (2019).

Aldridge, R. W. et al. Global patterns of mortality in international migrants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet 392(10164), 2553–2566. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32781-8 (2018).

Vandentorren, S. et al. Characteristics and health of homeless families: The ENFAMS survey in the Paris region, France 2013. Eur. J. Public Health 26(1), 71–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv187 (2016).

Nielsen, S. S. & Krasnik, A. Poorer self-perceived health among migrants and ethnic minorities versus the majority population in Europe: A systematic review. Int. J. Public Health 55(5), 357–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-010-0145-4 (2010).

Li, N., Strobino, D., Ahmed, S. & Minkovitz, C. S. Is there a healthy foreign born effect for childhood obesity in the United States?. Matern. Child Health J. 15(3), 310–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-010-0588-5 (2011).

Florian, S., Ichou, M. & Panico, L. Parental migrant status and health inequalities at birth: The role of immigrant educational selectivity. Soc. Sci. Med. 278, 113915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113915 (2021).

Alidu, L. & Grunfeld, E. A. A systematic review of acculturation, obesity and health behaviours among migrants to high-income countries. Psychol. Health 33(6), 724–745. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2017.1398327 (2018).

Waters, M. C., Tran, V. C., Kasinitz, P. & Mollenkopf, J. H. Segmented assimilation revisited: Types of acculturation and socioeconomic mobility in young adulthood. Ethn. Racial Stud. 33(7), 1168–1193. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419871003624076 (2010).

Kadawathagedara, M. et al. Diet during pregnancy: Influence of social characteristics and migration in the ELFE cohort. Matern. Child Nutr. 17(3), 13140. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13140 (2021).

Allen, J. D. et al. Pathways between acculturation and health behaviors among residents of low-income housing: The mediating role of social and contextual factors. Soc. Sci. Med. 123, 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.034 (2014).

Auger, N., Luo, Z. C., Platt, R. W. & Daniel, M. Do mother’s education and foreign born status interact to influence birth outcomes? Clarifying the epidemiological paradox and the healthy migrant effect. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 62(5), 402–409. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2007.064535 (2008).

Trigwell, J., Watson, P., Murphy, R., Stratton, G. & Cable, N. Ethnic differences in parental attitudes and beliefs about being overweight in childhood. Health Educ. J. 73(2), 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896912471035 (2014).

Buksh, M. J. et al. Relationship between BMI and adiposity among different ethnic groups in 2-year-old New Zealand children. Br. J. Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000711451800380X (2019).

D’Angelo, S. et al. Body size and body composition: A comparison of children in India and the UK through infancy and early childhood. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 69(12), 1147–1153. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-204998 (2015).

Deurenberg, P. Universal cut-off BMI points for obesity are not appropriate. Br. J. Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1079/BJN2000273 (2000).

Beauchamp, A., Backholer, K., Magliano, D. & Peeters, A. The effect of obesity prevention interventions according to socioeconomic position: a systematic review: Obesity prevention and socioeconomic position. Obes. Rev. 15(7), 541–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12161 (2014).

Langfield, T., Marty, L., Inns, M., Jones, A. & Robinson, E. Healthier diets for all? A systematic review and meta-analysis examining socioeconomic equity of the effect of increasing availability of healthier foods on food choice and energy intake. Obes. Rev. 24, 13565. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13565 (2023).

Surkan, P. J., Tabrizi, M. J., Lee, R. M., Palmer, A. M. & Frick, K. D. Eat right-live well! Supermarket intervention impact on sales of healthy foods in a low-income neighborhood. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 48(2), 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2015.09.004 (2016).

Pechey, R. & Monsivais, P. Socioeconomic inequalities in the healthiness of food choices: Exploring the contributions of food expenditures. Prev. Med. 88, 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.04.012 (2016).

Lioret, S. et al. The effectiveness of interventions during the first 1000 days to improve energy balance-related behaviors or prevent overweight/obesity in children from socio-economically disadvantaged families of high-income countries: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 24(1), 13524. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13524 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank all investigators working on the EndObesity Project. This project received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the ERA-NET Cofund action (grant agreement no. 727565) and the European Joint Programming Initiative “A Healthy Diet for a Healthy Life” (JPI HDHL, EndObesity). We used variables that were harmonized in the framework of the H2020 LifeCycle project. The LifeCycle project received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement no. 733206 LifeCycle). We thank the scientific coordinators (B. Geay, H. Léridon, C. Bois, J. L. Lanoé, X. Thierry and C. Zaros), IT and data managers, statisticians (M. Cheminat, C. Ricourt, A. Candea and S. de Visme), administrative and family communication staff, and study technicians (C. Guevel, M. Zoubiri, L. G. L. Gravier, I. Milan and R. Popa) of the ELFE coordination team as well as the families that gave their time for the study. We also thank the French Institute for Demographic Studies (INED) researchers for the sociodemographic variables created as part of the ANR-funded Veniromond project. This study was funded by two grants from the French National Research Agency (ANR-12-DSSA-0001, within the framework “Social determinants of health”; and ANR-19-CE36–0006). The ELFE study is a joint project between the French Institute for Demographic Studies (INED) and the National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM), in partnership with the French blood transfusion service (Etablissement français du sang [EFS]), Santé publique France, the National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE), the Direction générale de la santé (DGS, part of the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs), the Direction générale de la prévention des risques (DGPR, Ministry for the Environment), the Direction de la recherche, des études, de l’évaluation et des statistiques (DREES, Ministry of Health and Social Affairs), the Département des études, de la prospective et des statistiques (DEPS, Ministry of Culture), and the Caisse nationale des allocations familiales (CNAF), with the support of the Ministry of Higher Education and Research and the Institut national de la jeunesse et de l’éducation populaire (INJEP). Via the RECONAI platform, it receives government grants managed by the National Research Agency under the “Investissements d’avenir” program (ANR-11-EQPX-0038, ANR-19-COHO-0001). The authors thank Laura Smales for her help in preparing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.L.G., B.H. and S.L. designed the research, wrote the manuscript and analysed the data. S.L., B.H., M.A.C., M.L., L.P., A.H.C., J.B., M.M., M.G., T.S., and J.L.L. reviewed drafts and provided critical feedback. All authors approved the final manuscript and were responsible for the final content of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in Table 1, where the column headings were incorrect. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Le Gal, C., Lecorguillé, M., Poncet, L. et al. Social patterning of childhood overweight in the French national ELFE cohort. Sci Rep 13, 21975 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48431-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48431-8

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.