Abstract

Social anxiety and paranoia often co-occur and exacerbate each other. While loneliness and negative schemas contribute to the development of social anxiety and paranoia separately, their role in the development of the two symptoms co-occurring is rarely considered longitudinally. This study examined the moment-to-moment relationship between social anxiety and paranoia, as well as the effects of loneliness and negative schemas on both experiences individually and coincidingly. A total of 134 non-clinical young adults completed experience sampling assessments of momentary social anxiety, paranoia, and loneliness ten times per day for six consecutive days. Participants’ negative-self and -other schemas were assessed with the Brief Core Schema Scale. Dynamic structural equation modelling revealed a bidirectional relationship between social anxiety and paranoia across moments. Loneliness preceded increases in both symptoms in the next moment. Higher negative-self schema was associated with a stronger link from paranoia to social anxiety; whereas higher negative-other schema was associated with a stronger link from social anxiety to paranoia. Our findings support the reciprocal relationship between social anxiety and paranoia. While loneliness contributes to the development of social anxiety and paranoia, negative self and other schemas appear to modify the relationships between the two symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Around one-fifth of individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders have a comorbid social anxiety disorder (see meta-analysis by McEnery et al.1), characterized by an excessive fear or anxiety about scrutiny from others in social situations2. Compared with patients without comorbidity, those with comorbid social anxiety disorder report lower quality of life, more severe depression, and a higher rate of suicide3,4,5. The level of social anxiety in schizophrenia spectrum disorders needs only be at a subclinical level to be associated with poorer functioning, both concurrently and longitudinally6. This suggests that social anxiety may contribute to poorer outcomes in individuals with psychosis, even when present at subclinical levels.

Paranoia, the exaggerated belief that intentional harm is done or will be done by others7, is a common symptom of psychosis. Paranoia can manifest in milder forms as ideas of social reference or more severe forms as persecutory delusions 8. Albeit being distinct phenomena, paranoia and social anxiety are both characterized by appraisals of social threat: paranoia concerns imminent and ongoing physical, psychological or social harms by others7, whereas social anxiety reflects worry about rejection, embarrassment and scrutiny9. Among individuals with first-episode psychosis, those with comorbid social anxiety disorder reported more persecutory threats than those without comorbidity3. Across non-patient and community samples, correlations between subclinical levels of social anxiety and paranoia are consistently found to be moderate to strong10,11,12,13.

The co-occurrence of social anxiety and paranoia raises questions about how the two symptoms may influence each other3,14. On the one hand, it has been proposed that paranoia develops against the backdrop of anxiety and related worry processes15,16,17. The cognitive model of paranoia posits that social evaluative concerns, which form the core of social anxiety, contribute as an antecedent of paranoia18. In a longitudinal study with a community sample, Aunjitsakul et al.19 found that social anxiety at baseline predicted an increase in paranoia at 3-month follow-up. On the other hand, social anxiety has also been proposed to be a consequence of paranoid thinking, which inflicts internalized stigma and shame20,21,22. Two longitudinal cohort studies with general population samples9,23 found that paranoia at baseline predicted subsequent emergence of social anxiety, but not vice versa. However, these studies did not examine both directions of relationship in the same model. Therefore the covariation of the symptoms, which is conceptually interactive in nature, was not taken into full consideration.

Delineating the temporal dynamics between social anxiety and paranoia will not only reveal their potential bidirectional relationship, but also allow for investigations of putative underlying mechanisms. As both social anxiety and paranoia are experiences derived from the social environment, how connected one feels to the surrounding social environment could be important to the manifestation of these symptoms. Loneliness, a negative experience arising from a mismatch between perceived and actual social relationships24, has recently been implicated in the development of both social anxiety and paranoia10,25,26,27. It has been proposed that loneliness triggers heightened vigilance towards social threats, with an aim to protect the thwarted social relationships from further deterioration24,28. Heightened vigilance for social threats could be driven by an increase in negative affect29 or an attention bias towards cues of social threat in the external environment30, which may in turn precipitate heightened social threat appraisals. A 3-wave longitudinal study with a community sample27 found that loneliness predicted increases in social anxiety and paranoia, even after controlling for depression (which often co-exists with loneliness). This finding supports loneliness as a common psychopathological pathway to the development of both social anxiety and paranoia.

Apart from loneliness, negative schemas (i.e. global and stable beliefs about the self and others) may also underlie the development of social anxiety and paranoia. Cognitive models of social anxiety18,31,32 and paranoia33,34 have suggested that both symptoms build on negative-self beliefs (e.g., “I am worthless and weak”), which facilitate appraisals that one is vulnerable to social threats. Paranoia is suggested to be specific to negative-other beliefs (e.g., “Others are harsh and bad”)10,35,36, leading to a biased interpretation of others’ intention as hostile and malevolent. Recently, a cognitive model of social anxiety in schizophrenia highlights the role of negative-self schema37. The model posits that negative social situations activate preexisting negative self-representation, leading to the appraisal of social threats in the forms of social anxiety and paranoia. While the model does not specify the role of negative-other schema, we expect negative-other schema to contribute to a stronger tendency towards the formation of paranoia (relative to social anxiety).

As social anxiety, paranoia and loneliness occur naturalistically in the flow of daily life with varying intensities across hours and days, they can be reliably captured by the experience sampling method (ESM). ESM refers to repeated self-report questionnaires that record subjective experiences across moments in the flow of daily life38. Compared to traditional retrospective questionnaires, ESM represents these experiences with less recall bias39, which is particularly important when investigating momentary beliefs and appraisals. Importantly, ESM data provides valuable insights into the temporal dynamics between variables (i.e. cross-lagged effects) while taking into account their tendency to carry over across time (i.e. autoregressive effects)40,41. The autoregressive effects represent the extent to which a variable at the previous moment t-1 predicts itself at the current moment t, indicating the carry-over effect within the same variable across moments. On the other hand, the cross-lagged effects represent the extent to which a variable at the previous moment t-1 predicts change in another variable at the current moment t, indicating the spill-over effect from a variable to another variable across moments.

While previous studies mainly recruited samples across a large age span, the current study focused on young adulthood (i.e. age 18–30), a life stage where people are most vulnerable to loneliness, social anxiety and paranoia42,43,44. The aim of the present study was threefold: First, we tested the moment-to-moment dynamics between social anxiety and paranoia. We hypothesized significant cross-lagged effects from social anxiety to paranoia and vice versa. Second, we examined the moment-to-moment dynamics between loneliness and the two symptoms. We hypothesized significant cross-lagged effects from loneliness to both social anxiety and paranoia. Third, we tested the associations of core schemas with the strength of the cross-lagged effects. We hypothesized that negative-self schema would increase the strength of the cross-lagged bi-directional effects between social anxiety and paranoia. We also hypothesized a positive association between negative-other schema and the strength of the cross-lagged effect from social anxiety to paranoia.

Results

Sample characteristics

One hundred and fifty-four participants consented and took part in the study. Twenty participants were excluded due to a past or current psychiatric diagnosis (n = 18), or a subthreshold completion rate of the ESM assessment (see ‘Methods’ section, n = 2). Therefore, the final sample consisted of ESM data from 134 participants. The majority of our sample consisted of undergraduate students (n = 116, 86.6%), while the remaining (n = 18, 13.4%) were adults from the general population. A total of 5,800 ESM entries were entered into the Dynamic Structural Equation Modelling (DSEM) analyses (mean completion rate: 72.1%, SD = 0.16, range = 36.7% – 100%). The mean duration between two consecutive ESM entries within a day was 80.18 min (SD = 19.31, range = 15–147). The descriptive statistics of participants’ demographic information and baseline survey can be found in Table 1.

Dynamic structural equation modelling (DSEM) analyses

The estimates of the fixed and random effects in Models 1 and 2 are shown in Table 2. For Model 1, there were significant autoregressive effects for both social anxiety (β = 0.50, 95% CrI [0.28, 0.73]) and paranoia (β = 0.47, 95% CrI [0.24, 0.71]), indicating carry-over effects of social anxiety and paranoia across moments. The cross-lagged effect from social anxiety to paranoia (β = 0.20, 95% CrI [0.01, 0.41]) and the cross-lagged effect from paranoia to social anxiety (β = 0.29, 95% CrI [0.06, 0.51]) were both significant. We found no gender differences in the strength of these cross-lagged effects (p > 0.050).

For Model 2, as shown in Table 2, the autoregressive effects of social anxiety (β = 0.41, 95% CrI [0.20–0.63]), paranoia (β = 0.31, 95% CrI [0.11, 0.52]) and loneliness (β = 0.61, 95% CrI [0.26–0.86]) were significant. The cross-lagged effects from loneliness to social anxiety (β = 0.26, 95% CrI [0.00, 0.52]) and paranoia (β = 0.21, 95% CrI [0.01, 0.42]) were both significant. There was also a significant cross-lagged effect from paranoia to social anxiety (β = 0.25, 95% CrI [0.04, 0.46]), but not vice versa (β = 0.19, 95% CrI [− 0.01, 0.40]). There were no gender differences in the strength of these cross-lagged effects (p > 0.050).

The between-person correlations between negative schemas and DSEM parameters for Model 2 are reported in Table 3. The level of negative-self was positively associated with the strength of the cross-lagged effect from paranoia to social anxiety (r = 0.32, 95% CrI [0.11, 0.51]). The level of negative-other schema was positively associated with the strength of the cross-lagged effect from social anxiety to paranoia (r = 0.30, 95% CrI [0.11, 0.49]), but negatively associated with the strength of the cross-lagged effect from loneliness to paranoia (r = − 0.23, 95% CrI [− 0.43, − 0.02]). Both levels of negative-self (rs = 0.35–0.45) and -other schemas (rs = 0.23–0.29) were associated with mean social anxiety, paranoia and loneliness.

Discussion

This study utilized ESM to repeatedly assess momentary symptoms in daily life and found that social anxiety predicted an increase in paranoia across moments and vice versa. Such reciprocal relationships were demonstrated in a sample of young adults in the absence of full-blown psychiatric disorders. These relationships did not differ between genders. Our findings showed that social anxiety and paranoia do not merely co-exist, but also dynamically interact with one another in their development and maintenance.

In addition to previous longitudinal studies which considered social anxiety and paranoia separately9,19,23, our analytical approach using DSEM focused on the covariation of both symptoms in a single model (Model 1). For the first time, we offered evidence for the bidirectional relationship within the same sample, revealing comparable effect sizes of each directional path. In addition to previous conceptualization of social anxiety as an antecedent to paranoia (e.g. cognitive model of paranoia, Freeman et al.18), our results also supported it as a consequence of paranoia as shown in other studies9,23. Future studies may clarify the overlap of paranoid thinking with the affective, cognitive and behavioral manifestations of social anxiety, which would inform the underlying processes in both symptoms.

We then took a closer look at loneliness in the moment-to-moment dynamics between social anxiety and paranoia (Model 2). We found that loneliness predicted an increase in both social anxiety and paranoia, corroborating with a longitudinal study with a community sample27. We confirmed the ‘healthy’ status of our sample with a psychiatric interview; therefore, our findings reflected the relationship between social anxiety and paranoia free from the confounding effects by treatments and chronicity of the psychiatric disorders. The convergent finding from Lim et al.27 and our study support loneliness as a common psychopathological pathway to both social anxiety and paranoia. While previous studies have found that loneliness leads to heightened vigilance for social threat via a myriad of affective and social-cognitive processes29,30, the contributions of these processes in differentiating social anxiety from paranoia outcomes need to be ascertained in further studies.

As hypothesized, the level of negative-self schema was associated with a stronger relationship from paranoia to social anxiety, whereas the level of negative-other schema was associated with a stronger relationship from social anxiety to paranoia. These findings were in line with the proposed role of negative beliefs about self (e.g. ‘I am worthless and weak’) in the formation of fear of rejection and criticism implicated in social anxiety31,32. The findings also supported the specificity between negative-other schema and paranoia10,35,36, where negative beliefs about others (e.g. ‘Others are harsh and bad’) would exacerbate the formation of paranoid thinking, possibly against the backdrop of social anxiety. Importantly, our findings highlighted the presence of both negative-self and -other schemas to be necessary to the maintenance of the reciprocal relationship between social anxiety and paranoia. This speculation is consistent with the finding of a recent latent profile analysis by Chau et al.10. They identified a subgroup of non-clinical young adults high on both social anxiety and paranoia, who reported more negative-self and -other schemas than subgroups high on either symptom. Future studies may examine how various constellations of negative-self- and -other schemas would shape the development of various phenotypic expressions of social anxiety and paranoia. Our findings also pave ways for future investigation of the potential between-person heterogeneity in these moment-to-moment dynamics, which may longitudinally predict the transition into social anxiety disorder, schizophrenia and their co-morbidity.

In sum, our findings offered support to Aunjitsakul et al.37’s unified framework for the understanding the psychopathological processes underlying social anxiety and paranoia. In particular, loneliness appears to be a situational trigger to the emergence of social anxiety and paranoia, in which their dynamics are strengthened by negative schemas. Our findings further extended Aunjitsakul et al.’s37 cognitive model with the role of negative-other schemas, which may exaggerate the appraisal of social threat in terms of harm and malevolence, which define paranoia35. Our findings shed light on the possibility of ameliorating social anxiety and paranoia via interventions that reduce loneliness45,46 or challenge negative-self and -other schemas (e.g. cognitive restructuring47,48,49).

There are several limitations of the current study. First, our results may be specific to the current sampling frequency of ESM assessment. Despite the statistical adjustment to confine the temporal effects to one-hour windows, it is inevitable that any effects that operate at shorter or longer time windows would be missed. Second, our data collection was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, a period when exacerbated loneliness, social anxiety and paranoia were reported50,51,52. Although the baseline levels of these phenomena were comparable to another sample of demographically diverse non-clinical young adults tested before the outbreak of the pandemic10 (N = 2089), we could not ascertain the confounding impact of the pandemic on the expression of these phenomena in daily life36. Third, a majority of our sample were undergraduate students. It is not sure whether our results would be replicated in demographically diverse samples. Finally, we acknowledge the possibility that the dynamics between social anxiety and paranoia may also involve other unmeasured mechanisms beyond loneliness and negative core schemas, such as interpersonal trauma53,54. This should be investigated in future research.

Using ESM, the current findings supported the reciprocal relationship between social anxiety and paranoia. Loneliness was also found to predict increases in both anxiety and paranoia across moments, suggesting that loneliness predates and may lead to the increases in both symptoms. Moreover, the strength of the dynamics between social anxiety and paranoia was associated with levels of negative-self and -other schemas. Our findings shed new light on the understanding of the dynamics between social anxiety and paranoia, which may invite replications in the clinical populations.

Methods

Ethics approval for the study was granted by the Survey and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee of The Chinese University of Hong Kong (Reference no.: SBRE-19–788). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Participants

Eligible participants aged 18–30 were recruited either from the subject pool of the Introductory Psychology course or via campus recruitment. Participants with any past or current psychiatric diagnosis (self-reported and then confirmed with a diagnostic clinical interview, see Measures) and who could not read Chinese were excluded. We targeted a sample size of 130, which is comparable to previous ESM studies with non-clinical samples analyzed using the dynamics structural equational modelling (DSEM) (see Statistical Analysis)55,56,57. Our targeted sample size fulfilled the sample size recommendation from a recent simulation study for DSEM58.

Procedure

Data collection took place in June to October 2021. It happened to be after the peak of the fourth wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong. While face-to-face data collection was allowed by the university, territory-wide infection control measures such as social distancing and mask-wearing mandate were in place. Consented participants attended a 1-h assessment session during which they were screened with the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (SCI-DSM-IV; So et al.59). Participants without any past or current psychiatric diagnosis completed a baseline survey, and were then briefed individually on the ESM procedure.

The ESM questionnaires were programmed into a smartphone app (SEMA360) installed on the participant’s mobile phone. Adopting a signal-contingent sampling design, the app prompted participants to answer the same set of items assessing momentary loneliness, social anxiety and paranoia (see Measures below) ten times a day for six consecutive days. The app displayed the items one by one in a way that the preceding item had to be answered before the next item would appear. The prompt signals were pseudo-randomized into blocks of time intervals within 13 waking hours. The starting time of the ESM assessment was tailored for each participant to maximize compliance. Consecutive ESM questionnaires were set at least 15 min apart. Each ESM questionnaire expired in 15 min. The participant completed at least one ESM questionnaire as practice under the guidance of a research worker.

Support was rendered to the participants by the research team throughout the ESM assessment period. On the first assessment day, a research worker contacted the participant to ensure that the app was functioning properly and to encourage them to answer to the ESM prompts. In the middle of the week, the research worker monitored the participant’s progress and offered help to increase their compliance when necessary. Participants could also contact the research team whenever they encountered any difficulties with the app. After completing the 6-day ESM assessment, participants received course credits or monetary compensation for their time.

Measures

Baseline survey

Participants completed retrospective questionnaires assessing levels of loneliness, paranoia, depression, and social anxiety. These included the UCLA-Loneliness Scale version 3 (UCLA-LS-v3)61, the Revised Green et al. Paranoid Thoughts Scale (R-GPTS)62, the Patient Health Questionannire-9 (PHQ-9)63 and the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale-6/Social Phobia Scale-6 (SIAS-6/SPS-6)64. The UCLA-LS-v3 and SIAS-6/SPS-6 do not specify the timeframe of reference, whereas PHQ-9 and R-GPTS assess depressive symptoms and paranoia within two weeks and one month respectively. The Chinese versions of these measures have been validated and used in previous studies10,26,36. Negative-self and -other schemas were measured with the respective subscales of the Brief Core Schema Scale65. Its Chinese version has been used in Chau et al.10 and So et al.36. Internal consistencies of these measures ranged from 0.78 to 0.93 in this sample. Items on age, gender, educational attainment, monthly household income and employment status were also included.

ESM assessment

All ESM measures were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 “not at all”–7 “very”).

Momentary loneliness

The 3-item UCLA Loneliness scale66 was modified to assess momentary loneliness (e.g., ‘I lack companionship right now’). These three items have been used in a previous ESM study29. In the current study, the within- and between-person reliabilities were 0.86 and 0.98 respectively.

Momentary social anxiety

Momentary social anxiety was assessed with the three items suggested in Kashdan and Steger67 (e.g., ‘I worried that I would say or do something wrong right now’). It has been used in previous ESM studies 68,69. In the current study, the within- and between-person reliabilities were 0.84 and 0.99 respectively.

Momentary paranoia

Momentary paranoia was assessed with the five items suggested by Schlier et al.70 (e.g., ‘People are trying to upset me right now’). These items have been used in previous ESM studies70,71,72. The within-(0.84) and between-person (0.99) reliabilities were good in the current study.

Statistical analysis

In accordance with previous ESM studies, responses from participants who completed less than one-third of the total ESM questionnaires (i.e. 20) were excluded from the data analysis73. Our hypotheses were tested with Dynamic Structural Equation Modeling (DSEM)40,41. DSEM allows the examination of multi-level relationships among ESM variables by decomposing the intensive longitudinal data into within- and between-person variance components using a latent person-mean approach. For the within-person components, the fixed effects of means of ESM variables (i.e. intercepts), their autoregressive effects and cross-lagged effects were simultaneously estimated in a single model. The autoregressive effects were estimated by regressing the variables at the current moment t on the same variables at the previous moment t-1, while the cross-lagged effects were estimated by regressing the variable at the current moment t on another variable at the previous moment t-1. To allow for inter-individual differences in these fixed effects, the DSEM estimated all the random effects at the between-person level, which were allowed to correlate with each other.

Bayesian estimation is supported in DSEM to estimate all random effects in a single model with high accuracy and computational efficiency. The default non-informative priors were used in this study. Four Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains with 5000 iterations each were used, with a thinning of 10. Missing data was assumed to be missing at random and handled with MCMC sampling40. Within-person standardized parameters of the fixed effects74 were computed for interpretation. Estimates of all fixed effects were regarded as statistically significant if their 95% credible intervals (CrIs) did not include zero. Tests for model comparison were not conducted, as model comparison is an underdeveloped area for DSEM40.

To control for potential trends or non-stationarity of ESM data, the hour of measurement was added in the within-person level of the DSEM models as fixed effects. Unequal time spacing of the ESM data was handled by creating time grids of one hour using a discrete time filter approach using the Mplus option TINTERVAL40. Therefore, the interpretation of all parameters was in reference to the time window of one hour. A simulation study indicated that estimates of parameters are unbiased up to 80–85% of missing data58.

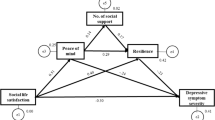

For the first hypothesis, we fitted the bivariate multilevel first-order vector autoregressive model (Model 1) with within-person cross-lagged effects between momentary social anxiety and paranoia, while controlling for their autoregressive effects (see schematic representation in Fig. 1). For the second hypothesis, we further added momentary loneliness into the model, creating a Model 2 that examined the within-person cross-lagged effects between loneliness, social anxiety and paranoia, while controlling for their autoregressive effects (see Fig. 2). As exploratory analyses, we also examined gender differences in these effects by adding gender as a predictor at the between-person level of these models. The third hypothesis was tested by the correlation between the random effects at the between-person level and the levels of negative-self and -other schemas, which were grand-mean centred before entering into the model.

Schematic representation of the DSEM model of social anxiety and paranoia (Model 1). Note: This figure is a schematic representation of the dynamic structural equation model of social anxiety and paranoia (Model 1). The left panel contains the decomposition of social anxiety and paranoia into within-person and between-person variance components respectively. The top right panel indicates the within-person level model, which is a vector autoregressive model. The bottom right panel indicates the between-person level model, which includes all the random effects of the model, corresponding to the solid black circles in the within-person level model. SA—social anxiety, PAR—paranoia.

Schematic representation of the DSEM model of loneliness, social anxiety and paranoia (Model 2). Note: This figure is a schematic representation of the dynamic structural equation model of social anxiety, paranoia and loneliness (Model 2). The left panel contains the decomposition of social anxiety, paranoia and loneliness into within-person and between-person variance components respectively. The top right panel indicates the within-person level model, which is a vector autoregressive model. The bottom right panel indicates the between-person level model, which includes the levels of negative-self and -other schemas, as well as all the random effects of the model, corresponding to the solid black circles in the within-person level model. SA—social anxiety, PAR—paranoia, LONE—loneliness, NS—negative-self subscore of the Brief Core Schema Scale, NO—negative-other subscore of the Brief Core Schema Scale.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

McEnery, C., Lim, M. H., Tremain, H., Knowles, A. & Alvarez-Jimenez, M. Prevalence rate of social anxiety disorder in individuals with a psychotic disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 208, 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2019.01.045 (2019).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edn. (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Michail, M. & Birchwood, M. Social anxiety disorder in first-episode psychosis: Incidence, phenomenology and relationship with paranoia. Br. J. Psychiat. 195, 234–241. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.053124 (2009).

Stefano Pallanti, M. D., Leonardo Quercioli, M. D. & Eric Hollander, M. D. Social anxiety in outpatients with schizophrenia: A relevant cause of disability. Am. J. Psychiat. 161, 53–58. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.1.53 (2004).

Vrbova, K., Prasko, J., Ociskova, M. & Holubova, M. Comorbidity of schizophrenia and social phobia—Impact on quality of life, hope, and personality traits: a cross sectional study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 13, 2073–2083. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S141749 (2017).

Nemoto, T. et al. Impact of changes in social anxiety on social functioning and quality of life in outpatients with schizophrenia: A naturalistic longitudinal study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 131, 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.08.007 (2020).

Freeman, D. & Garety, P. A. Comments on the content of persecutory delusions: Does the definition need clarification?. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 39, 407–414. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466500163400 (2000).

Freeman, D. et al. Psychological investigation of the structure of paranoia in a non-clinical population. Br. J. Psychiat. 186, 427–435. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.186.5.427 (2005).

Rietdijk, J., van Os, J., Graaf, R. D., Delespaul, P. & Gaag, M. V. D. Are social phobia and paranoia related, and which comes first?. Psychosis 1, 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/17522430802654105 (2009).

Chau, A. K. C. et al. The co-occurrence of multidimensional loneliness with depression, social anxiety and paranoia in non-clinical young adults: A latent profile analysis. Front. Psychiat. 13, 931558. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.931558 (2022).

Horton, L. E., Barrantes-Vidal, N., Silvia, P. J. & Kwapil, T. R. Worries about being judged versus being harmed: disentangling the association of social anxiety and paranoia with schizotypy. PLoS ONE 9, e96269. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096269 (2014).

Matos, M., Pinto-Gouveia, J. & Gilbert, P. The effect of shame and shame memories on paranoid ideation and social anxiety. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 20, 334–349. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1766 (2013).

Tone, E. B., Goulding, S. M. & Compton, M. T. Associations among perceptual anomalies, social anxiety, and paranoia in a college student sample. Psychiat. Res. 188, 258–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.03.023 (2011).

Maria, M. in New Insights into Anxiety Disorders (ed Durbano Federico) Ch. 7 (IntechOpen, 2013).

Bird, J. C., Waite, F., Rowsell, E., Fergusson, E. C. & Freeman, D. Cognitive, affective, and social factors maintaining paranoia in adolescents with mental health problems: A longitudinal study. Psychiat. Res. 257, 34–39 (2017).

Startup, H. et al. Worry processes in patients with persecutory delusions. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 55, 387–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12109 (2016).

Sun, X., So, S. H., Chan, R. C. K., Chiu, C. D. & Leung, P. W. L. Worry and metacognitions as predictors of the development of anxiety and paranoia. Sci. Rep. 9, 14723. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-51280-z (2019).

Freeman, D., Garety, P. A., Kuipers, E., Fowler, D. & Bebbington, P. E. A cognitive model of persecutory delusions. Brit. J. Clin. Psychol. 41, 331–347. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466502760387461 (2002).

Aunjitsakul, W., McLeod, H. J. & Gumley, A. Investigating key mechanisms mediating the relationship between social anxiety and paranoia: A 3-month follow-up cross-cultural survey conducted in Thailand and the United Kingdom. Psychiat. Res. Commun. 2, 100028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psycom.2022.100028 (2022).

Michail, M. & Birchwood, M. Social anxiety disorder and shame cognitions in psychosis. Psychol. Med. 43, 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712001146 (2013).

Birchwood, M. et al. Social anxiety and the shame of psychosis: A study in first episode psychosis. Behav. Res. Therapy 45, 1025–1037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.07.011 (2007).

Michail, M. In New Insights into Anxiety Disorders (ed Durbano Federico) Ch. 7 (IntechOpen, 2013).

Schutters, S. I. J. et al. The association between social phobia, social anxiety cognitions and paranoid symptoms. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 125, 213–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01787.x (2012).

Cacioppo, J. T. & Hawkley, L. C. Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 13, 447–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005 (2009).

Bell, V. et al. Do loneliness and social exclusion breed paranoia? An experience sampling investigation across the psychosis continuum. Schizophr. Res. Cogn. 33, 100282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scog.2023.100282 (2023).

Chau, A. K. C. et al. A network analysis on the relationship between loneliness and schizotypy. J. Affect. Disorders 311, 148–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.05.057 (2022).

Lim, M. H., Rodebaugh, T. L., Zyphur, M. J. & Gleeson, J. F. M. Loneliness over time: The crucial role of social anxiety. J. Abnormal Psychol. 125, 620–630. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000162 (2016).

Hawkley, L. C. & Cacioppo, J. T. Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 40, 218–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8 (2010).

Meng, J., Wang, X., Wei, D. & Qiu, J. State loneliness is associated with emotional hypervigilance in daily life: A network analysis. Personal. Individual Differ. 165, 110154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110154 (2020).

Tanaka, H. & Ikegami, T. Fear of negative evaluation moderates effects of social exclusion on selective attention to social signs. Cogn. Emotion 29, 1306–1313. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2014.977848 (2015).

Clark, D. M. & Wells, A. Social Phobia: Diagnosis, Assessment, and Treatment (The Guilford Press, 1995).

Wong, Q. J. J. & Rapee, R. M. The aetiology and maintenance of social anxiety disorder: A synthesis of complementary theoretical models and formulation of a new integrated model. J. Affect. Disorders 203, 84–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.069 (2016).

Monsonet, M., Amedy, A., Kwapil, T. R. & Barrantes-Vidal, N. A psychosocial pathway to paranoia: The interplay between social connectedness and self-esteem. Schizophr. Res. 254, 199–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2023.03.006 (2023).

Murphy, P., Bentall, R. P., Freeman, D., O’Rourke, S. & Hutton, P. The paranoia as defence model of persecutory delusions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiat. 5(11), 913–929. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30339-0 (2018).

Humphrey, C., Bucci, S., Varese, F., Degnan, A. & Berry, K. Paranoia and negative schema about the self and others: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 90, 102081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102081 (2021).

So, S.H.-W. et al. Pandemic paranoia, general paranoia, and their relationships with worry and beliefs about self/others—A multi-site latent class analysis. Schizophr. Res. 241, 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2022.01.045 (2022).

Aunjitsakul, W., McGuire, N., McLeod, H. J. & Gumley, A. Candidate factors maintaining social anxiety in the context of psychotic experiences: A systematic review. Schizophr. Bull. 47, 1218–1242. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbab026 (2021).

Trull, T. J. & Ebner-Priemer, U. Ambulatory Assessment. Ann. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 9, 151–176. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185510 (2013).

Shiffman, S., Stone, A. A. & Hufford, M. R. Ecological momentary assessment. Ann. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 4, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415 (2008).

Hamaker, E. L., Asparouhov, T., Brose, A., Schmiedek, F. & Muthén, B. At the frontiers of modeling intensive longitudinal data: dynamic structural equation models for the affective measurements from the COGITO study. Multivar. Behav. Res. 53, 820–841. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2018.1446819 (2018).

Hamaker, E., Asparouhov, T. & Muthén, B. Dynamic structural equation modeling as a combination of time series modeling, multilevel modeling, and structural equation modeling. Handb. Struct. Eq. Model. 31, 859625 (2021).

Buecker, S., Mund, M., Chwastek, S., Sostmann, M. & Luhmann, M. Is loneliness in emerging adults increasing over time? A preregistered cross-temporal meta-analysis and systematic review. Psychol. Bull. 147, 787–805. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000332 (2021).

Jefferies, P. & Ungar, M. Social anxiety in young people: A prevalence study in seven countries. PLOS ONE 15, e0239133. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239133 (2020).

Freeman, D. et al. Concomitants of paranoia in the general population. Psychol. Med. 41, 923–936. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291710001546 (2011).

Lim, M. H. et al. A pilot digital intervention targeting loneliness in young people with psychosis. Soc. Psychiat. Psychiat. Epidemiol. 55, 877–889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01681-2 (2020).

Lim, M. H., Penn, D. L., Thomas, N. & Gleeson, J. F. M. Is loneliness a feasible treatment target in psychosis?. Soc. Psychiat. Psychiat. Epidemiol. 55, 901–906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01731-9 (2020).

Freeman, D. et al. An early Phase II randomised controlled trial testing the effect on persecutory delusions of using CBT to reduce negative cognitions about the self: The potential benefits of enhancing self confidence. Schizophr. Res. 160, 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2014.10.038 (2014).

McEnery, C. et al. Social anxiety in young people with first-episode psychosis: Pilot study of the EMBRACE moderated online social intervention. Early Interv. Psychiat. 15, 76–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12912 (2021).

Halperin, S., Nathan, P., Drummond, P. & Castle, D. A cognitive-behavioural, group-based intervention for social anxiety in schizophrenia. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiat. 34, 809–813. https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1440-1614.2000.00820.x (2000).

Ernst, M. et al. Loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Am. Psychol. 77, 660–677. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001005 (2022).

Kindred, R. & Bates, G. W. The Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on social anxiety: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20, 2362 (2023).

Suthaharan, P. et al. Paranoia and belief updating during the COVID-19 crisis. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 1190–1202. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01176-8 (2021).

Michail, M. & Birchwood, M. Social anxiety in first-episode psychosis: The role of childhood trauma and adult attachment. J. Affect. Disorders 163, 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.033 (2014).

Spinhoven, P. et al. The specificity of childhood adversities and negative life events across the life span to anxiety and depressive disorders. J. Affect. Disorders 126, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.02.132 (2010).

Blanke, E. S., Neubauer, A. B., Houben, M., Erbas, Y. & Brose, A. Why do my thoughts feel so bad? Getting at the reciprocal effects of rumination and negative affect using dynamic structural equation modeling. Emotion 22, 1773–1786. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000946 (2022).

Hjartarson, K. H., Snorrason, I., Bringmann, L. F., Ögmundsson, B. E. & Ólafsson, R. P. Do daily mood fluctuations activate ruminative thoughts as a mental habit? Results from an ecological momentary assessment study. Behav. Res. Therapy 140, 103832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2021.103832 (2021).

Tammilehto, J. et al. Dynamics of attachment and emotion regulation in daily life: Uni- and bidirectional associations. Cogn. Emotion 36, 1109–1131. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2022.2081534 (2022).

Schultzberg, M. & Muthén, B. Number of subjects and time points needed for multilevel time-series analysis: a simulation study of dynamic structural equation modeling. Struct. Eq. Model. Multidiscip. J. 25, 495–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2017.1392862 (2018).

So, E. et al. The Chinese-bilingual SCID-I/P project: Stage 1–reliability for mood disorders and schizophrenia, Hong Kong. J. Psychiat. 13, 7 (2003).

SEMA3: Smartphone Ecological Momentary Assessment, Version 3 (2019).

Russell, D. W. UCLA loneliness scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. J. Personal. Assess. 66, 20–40. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2 (1996).

Freeman, D. et al. The revised Green et al, Paranoid Thoughts Scale (R-GPTS): Psychometric properties, severity ranges, and clinical cut-offs. Psychol. Med. 51, 244–253. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719003155 (2021).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. W. The PHQ-9. J. General Intern. Med. 16, 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x (2001).

Peters, L., Sunderland, M., Andrews, G., Rapee, R. M. & Mattick, R. P. Development of a short form Social Interaction Anxiety (SIAS) and Social Phobia Scale (SPS) using nonparametric item response theory: The SIAS-6 and the SPS-6. Psychol. Assess. 24, 66–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024544 (2012).

Fowler, D. et al. The Brief Core Schema Scales (BCSS): psychometric properties and associations with paranoia and grandiosity in non-clinical and psychosis samples. Psychol. Med. 36, 749–759 (2006).

Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C. & Cacioppo, J. T. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Res. Aging 26, 655–672 (2004).

Kashdan, T. B. & Steger, M. F. Expanding the topography of social anxiety: An experience-sampling assessment of positive emotions, positive events, and emotion suppression. Psychol. Sci. 17, 120–128 (2006).

Kashdan, T. B. et al. A contextual approach to experiential avoidance and social anxiety: Evidence from an experimental interaction and daily interactions of people with social anxiety disorder. Emotion 14, 769–781. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035935 (2014).

Kashdan, T. B. et al. Distinguishing healthy adults from people with social anxiety disorder: Evidence for the value of experiential avoidance and positive emotions in everyday social interactions. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 122, 645–655. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032733 (2013).

Schlier, B., Moritz, S. & Lincoln, T. M. Measuring fluctuations in paranoia: Validity and psychometric properties of brief state versions of the Paranoia Checklist. Psychiat. Res. 241, 323–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.05.002 (2016).

Bahlinger, K., Lincoln, T. M. & Clamor, A. Are acute increases and variability in emotion regulation strategies related to negative affect and paranoid thoughts in daily life?. Cogn. Therap. Res. 46, 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-021-10253-1 (2022).

Bahlinger, K., Lincoln, T. M., Krkovic, K. & Clamor, A. Linking psychophysiological adaptation, emotion regulation, and subjective stress to the occurrence of paranoia in daily life. J. Psychiat. Res. 130, 152–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.07.021 (2020).

Palmier-Claus, J. E. et al. Experience sampling research in individuals with mental illness: Reflections and guidance. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 123, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01596.x (2011).

Schuurman, N. K., Ferrer, E., de Boer-Sonnenschein, M. & Hamaker, E. L. How to compare cross-lagged associations in a multilevel autoregressive model. Psychol. Methods 21, 206–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000062 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for all the study participants for giving up their time to join the study.

Funding

The study was supported by the Seed Funding Support for Thesis Research 2019–20, Faculty of Social Science, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, and the Research Grants Council (GRF grant 14605020). A.K.C.C was supported by the Vice Chancellor’s Discretionary Fund of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K.C.C. and S.H.S. designed the study and wrote the protocol. A.K.C.C managed the data collection, overseen by S.H.S. and E.B.; A.K.C.C. undertook the statistical analysis. A.K.C.C. and S.H.S. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chau, A.K.C., So, S.Hw. & Barkus, E. The role of loneliness and negative schemas in the moment-to-moment dynamics between social anxiety and paranoia. Sci Rep 13, 20775 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-47912-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-47912-0

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.