Abstract

Little is known about disease-modifying drug (DMD) initiation by immigrants with multiple sclerosis (MS) in countries with universal health coverage. We assessed the association between immigration status and DMD use within 5-years after the first MS-related healthcare encounter. Using health administrative data, we identified MS cases in British Columbia (BC), Canada. The index date was the first MS-related healthcare encounter (MS/demyelinating disease-related diagnosis or DMD prescription filled), and ranged from 01/January/1996 to 31/December/2012. Those included were ≥ 18 years old, BC residents for ≥ 1-year pre- and ≥ 5-years post-index date. Persons becoming permanent residents 1985–2012 were defined as immigrants, all others were long-term residents. The association between immigration status and any DMD prescription filled within 5-years post-index date (with the latest study end date being 31/December/2017) was assessed using logistic regression, reported as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We identified 8762 MS cases (522 were immigrants). Among immigrants of lower SES, odds of filling any DMD prescription were reduced, whereas they did not differ between immigrants and long-term residents across SES quintiles (aOR 0.96; 95%CI 0.78–1.19). Overall use (odds) of a first DMD within 5 years after the first MS-related encounter was associated with immigration status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Canada’s long history of immigration, combined with its universal health care coverage and high prevalence of multiple sclerosis (MS) makes it an ideal region to study health service use in immigrants with MS. According to Statistics Canada’s Census data, in 2021 over one in five of the population (23%) were, or had ever been, a landed immigrant or permanent resident1. In addition, most (> 50%) of Canada’s recent immigrants entered under the economic category, while over one-third (35%) came via one of the skilled worker programs. While historically, the majority of immigrants came from Europe, this is no longer true, with most now coming from Asia, including the Middle East (62%), with 19% of all immigrants born in India and 10% from Europe. Nonetheless, the most (93%) recent immigrants could conduct a conversation in either of Canada’s official languages (English or French)1.

MS is a life-altering, chronic immune-mediated disease resulting in lesions and neurodegeneration in the brain and spinal cord. MS typically first presents in young to middle-aged adults, with most diagnosed between the ages of 20–50 years, and is the most common cause of non-traumatic neurologic disability in young adults2. Although there is no known cure for MS, it is now a treatable disease, with over 20 different disease-modifying drugs (DMD) approved for use. However, despite the potential barriers to health care which often disproportionately affect immigrants, including cultural and financial3, much remains unknown regarding use of these DMDs by immigrants with MS in countries, such as Canada, with universal health coverage. Prior work from Ontario, Canada found that, as compared to long-term residents, immigrants with MS had a lower socioeconomic status (SES) and also differed in terms of health care use. For example, while the rates of outpatient neurology visits were somewhat lower in the year before MS diagnosis (adjusted rate ratio 0.93; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.87–0.99), rates were higher in the year during and after MS diagnosis (adjusted rate ratios 1.17; 95% CI 1.12–1.23 and 1.16; 95% CI 1.10–1.23, respectively)4. Hospitalization rates were higher during the year of diagnosis, but lower post-diagnosis. However, whether access to a DMD was affected could not be examined because population-based prescription drug data are not available for persons under age 65 years.

A recent call-to-action highlighted the need for better understanding of potential health disparities among immigrants, and the role of social determinants of health and consequent inequities in MS care that may underpin those disparities5. Key gaps in knowledge included the lack of fundamental epidemiological descriptions of healthcare use by immigrants, such as access to, and use of, one of the mainstays of MS management—the DMDs used to treat MS. Therefore, we assessed the relationship between immigration status and initiation of a DMD. We focused on the 5 years after a first MS-related healthcare encounter, in part because early [versus delayed] DMD treatment may result in better MS outcomes6. Further, we explored whether SES had a differential impact on DMD initiation between immigrants and long-term residents. We hypothesized that, despite universal health care coverage, DMD initiation would be lower in immigrants relative to long-term residents, and that it would be lowest for immigrants living in the most socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods.

Results

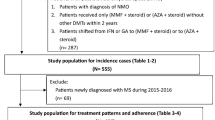

Overall, 8762 MS cases were identified (Fig. 1). Of these, 6% were immigrants. There was a similar female predominance for the immigrants and long-term residents, Table 1 (Pearson’s Chi Squared test p value 0.05, degree of freedom [df] 1).

Most immigrants were resident in Asia (41%) or Europe (34%) before moving to Canada; 13% were refugees. A higher proportion of immigrants fell within the lowest (most deprived) SES quintile at the index date compared to long-term residents (23% versus 18%), Table 1 (Pearson’s Chi squared test p value 0.02, df 4). More than three-quarters of immigrants (76%) and long-term residents (77%) had no comorbidity at the index date, as measured using the Charlson Comorbidity Index, Table 1 (Pearson’s Chi squared test p value 0.90, df 3).

DMD use was captured within 5 years of the index date, thus the maximum relevant follow-up period was 1996–2009 for the index date group 1996–2004 and 2005–2017 for the index date group 2005–2012. More than one-quarter of immigrants (26%; 138/522) and 23% of long-term residents (1889/8240) filled a DMD prescription within 5 years after the index date, Table 1 (Fisher’s exact test p value 0.90). After adjusting for sex, age, comorbidity score, SES, and calendar years at the index date, the odds of filling a DMD prescription within 5 years after the index date were similar between immigrants and long-term residents with MS (aOR 0.96; 95% CI 0.78–1.19). In the analysis that included SES and immigration status, we observed a 17% decrease in the odds of filling a DMD prescription within 5 years after the index date for each decrease in SES quintile (representing a decrease in neighborhood-level income) for immigrants (aOR per SES-quintile decrease: 0.83; 95% CI 0.72–0.96) but not for long-term residents (aOR 0.99; 95% CI 0.95–1.03). Thus, at the lowest income quintile, the odds of filling a DMD became 32% (aOR 0.68; 95% CI 0.47–0.98) lower for the immigrants versus long-term residents (Table 2).

Post-hoc, we described the mode of DMD administration for persons who had filled a DMD prescription within the 5-year period (Table 2). Most immigrants (94.2%) and long-term residents (96.7%) first used an injectable drug (beta-interferon, glatiramer acetate), Table 1 (Fisher’s exact test p value 0.14). Although there was a suggestion that immigrants were more likely to use an oral or intravenous DMD (5.8% of immigrants did so versus 3.3% of long-term residents), a higher proportion of immigrants (versus long-term residents) also had their index date in later years (2005–2012) when oral and intravenous DMDs were available.

Discussion

In this population-based study, the overall use (odds) of a first DMD prescription fill within 5 years after the first MS-related healthcare encounter was similar between immigrants and long-term residents in BC, Canada. However, immigrants with a lower (versus higher) area-level SES, based on neighborhood-level income, had lower odds of filling a first DMD prescription, while this association was not seen in long-term residents. Therefore, our hypothesis was confirmed. This suggests that intersectionality of immigrant status and SES contributes to disparities in DMD access5. Whether this adversely affects outcomes for immigrants with MS warrants future study.

DMD use in immigrants has seldom been reported, and there were few studies with which to compare our findings. A largely descriptive, population-based study from France (1995–2007) which focused on DMD-treated individuals suggested that immigrants (n = 133, all of whom were from North Africa) were treated earlier with a DMD, as compared to 2288 age- and sex matched MS cases from across continental Europe (1.3 versus 4.5 years after MS diagnosis)7. A smaller study from Oslo, Norway observed that for persons diagnosed with MS after the first DMDs became available (i.e., 1997) a somewhat higher proportion (71%; 27/38) of non-Western immigrants (from the Middle East, Asia, Africa or South/Central America) compared to 59% (143/241) of Norwegian individuals used any DMD treatment over the 6 year study period (1997–2012)8. While differences in study design, and also the time periods studied, makes it rather difficult to compare across articles, reassuringly both these studies and ours suggest that overall, of the relatively few immigrants studied to date, differences in DMD initiation by immigration status have not been observed, at least at the broad level in regions with access to universal healthcare. However, our findings indicated that health disparities amongst immigrants were affected by SES; the odds of filling a first DMD prescription was nearly one-third (32%) lower for those in the lowest, i.e., least affluent, SES quintile, relative to long-term residents in that same quintile. Health disparities related to socioeconomic inequities have been well-recognized in the wider population and represent a significant public health challenge9. Even within regions, such as Canada, with universal healthcare coverage, health disparities persist in lower socioeconomic groups, indicating that equitable availability of healthcare services alone is insufficient to address such disparities comprehensively9, 10. Individuals, including immigrants from lower socioeconomic groups can face several barriers that impact their overall health, including, although not limited to, health literacy, transportation challenges, work obligations, and cultural beliefs11,12,13. Lower SES has been associated with a higher disease burden, including higher rates of physical and mental health morbidities, and higher mortality rates in both the MS and general populations4, 9, 14,15,16,17, with immigrants often disproportionately affected by comorbidities18. A deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms driving these disparities in the MS population and impact on health outcomes could help inform evidence-based interventions for reducing health inequalities.

Our study has several limitations. Our immigration-related information was only available up until 2012, limiting our index date to 1996–2012. Further, our analysis lacked MS-specific clinical information such as relapses and disease severity. It would be of interest for future studies to consider the clinical status of immigrants in relation to DMD uptake. For example, prior work from Canada found that immigrants had a higher rate of hospitalizations in the year of their MS diagnosis versus long-term residents (adjusted rate ratio 1.20; 95% CI 1.04–1.39)4. This could suggest that immigrants were experiencing a more severe disease course even at presentation (diagnosis). Diagnostic delays in other under-represented or marginalized groups have been reported, including in MS5. This can lead to higher disability at the time of diagnosis, and possibly a greater need to treat rapidly with highly effective DMDs5. Whether immigrants have an actual altered risk of MS is less clear; a 2019 Canadian study found that MS incidence varied widely by region of origin, being higher for some regions, such as the Middle East, while lower for most others, as compared to immigrations from Western regions. MS incidence also varied by time spent resident in Canada19. Further work is warranted to explore all these issues further. Due to the cohort size and the lack of information on the duration of residency in the province for all members of the cohort, we were constrained in performing subgroup analyses (e.g., by age20 as ≤ 6 immigrants and ≤ 6 long-term residents aged ≥ 55 years at the index date had ever filled a DMD prescription). Strengths of our study included the use of linked health administrative data, and the large, geographically-defined MS population identified within a region providing universal healthcare, which included access to the DMDs to treat MS. Moreover, the mandatory enrollment in the publicly available health system virtually eliminates volunteer or selection bias and the prospective collection of the data ensure that our findings are not affected by recall bias.

To conclude, the use (odds) of any DMD to treat MS within 5 years after a first MS-related healthcare encounter differed between immigrants and long-term residents in a universal health care setting: SES affected findings, suggesting that immigrants (but not long-term residents) living in lower (versus higher) income neighborhoods may face health disparities, at least when it comes to prompt use of a DMD to treat MS. How this affects longer term outcomes for immigrants with MS, and what factors may drive potential health disparities for these individuals, requires consideration.

Methods

Data sources and cohort creation

We performed a population-based study in the province of British Columbia (BC), Canada using linked health administrative data. BC has a public healthcare plan, with mandatory enrollment for residents. Encounters with the healthcare system are routinely collected, including physician and hospital visits and prescription drugs dispensed in the community or outpatient setting. Across Canada, over 98% of the population (comprising both immigrants and long-term residents) have access to medically necessary services without user fees, including consultations with specialists or general physicians for the treatment of chronic diseases such as MS21. Data access was facilitated by Population Data BC and databases used included: Medical Service Plan Billing Information (providing physician visits [‘claims’])22 and the Discharge Abstract Database (providing hospital admissions/discharges)23. Both provided diagnoses made by physicians, coded using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) system. PharmaNet provided information on prescriptions filled at outpatient/community pharmacies, including dates and unique drug identification numbers24. Census Geodata provided SES estimates based on the median neighborhood-level income. Neighborhood income was derived by linking the individual’s postal code to the census dissemination area, using a Statistics Canada algorithm25. Registration and Premium Billing files provided demographics (sex, date of birth, and place of residency via the first 3-digits of each person’s postal code) and confirmation of residency in BC via days registered in the mandatory healthcare plan26. Vital Statistics captured death dates27. Finally, the Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada Permanent Residents dataset28 captured all landed permanent residents in Canada (1985–2012) and included refugee status and country of last permanent residence.

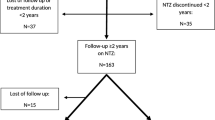

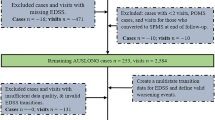

We identified MS cases using a validated algorithm requiring the presence of at least three MS-specific ICD codes (ICD-9 340 and ICD-10-CA G35) related to a hospitalization or physician visit in any combination, or at least one prescription filled for an MS DMD (Table 3)29. For example, an individual could fulfill the algorithm if they had three ICD-9 340 codes, or two ICD-9 340 and one ICD-10-CA G35 codes, and so on. The date of the first MS-related healthcare encounter defined the index date. Tables 3 and 4 show all relevant ICD codes and DMDs. MS cases were eligible for inclusion if they were: ≥ 18 years old at the index date and resident in BC for > 90% of the days in the year pre-index date30. The earliest possible index dates were 1-January-1996 and latest were 31-December-2012. Both dates reflect data availability; prescription data started 1-January-1996 and the immigration data ended 31-December-2012. Also, 1996 was the first full calendar year that the DMDs became available to treat MS in Canada. MS cases were categorized as an immigrant or long-term resident. Immigrants were defined as persons with a record of being a landed permanent resident at any time between 1985 and 2012. All others were considered long-term residents (i.e., persons who had received landed permanent resident status before 1985 or who had always resided in Canada). All persons were followed from their index date until the earliest of emigration from BC (i.e., end of mandatory healthcare plan registration), death or study end (31-December-2017). At least 5 years of follow-up (inclusive of the index date) were required in order to examine the study outcome—any DMD prescription filled within the five years post-index date. This five year period represented ‘early’ initiation of a DMD which is thought to result in better MS outcomes6. Five years also represented the time between the latest possible index date (31-December-2012) and the latest study end (31-December-2017), thus maximizing the number of eligible persons.

The outcome of any DMD prescription filled in the 5-years post-index date was categorized as ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Over the study period (1996–2017), the available DMDs comprised: the injectable (beta-interferon and glatiramer acetate); oral (fingolimod, dimethyl fumarate and teriflunomide), and intravenous (natalizumab) drugs. While daclizumab, alemtuzumab and ocrelizumab were available, these were never used as the first DMD within our MS population. Further details, including brand names and DMD identification numbers are in Table 3.

Statistical analysis

We described characteristics at the index date according to immigration status including sex, age, calendar years (i.e., 1996–1999, 2000–2004, 2005–2009, 2010–2012), SES (quintiles ranging from 1 [lowest income quintile, i.e., most deprived] to 5 [highest income quintile, i.e., most affluent]), comorbidity score (0, 1, 2, and ≥ 3) measured using the modified Charlson Comorbidity Index31 (based on physician/hospital data during the 1-year period pre-index date), and the number of persons filling a DMD within 5 years after the index date. For immigrants only, we described their refugee status and place of last permanent residence (grouped by region: Asia, Europe, United States of America, Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Oceania). We assessed the relationship between immigration status and filling a DMD prescription within 5 years post-index date using a logistic regression model, adjusted for sex, and, at the index date: age (continuous), comorbidity score, SES, and calendar years (see above). Findings were reported as adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% CIs. Pearson’s Chi-squared test (sex, calendar period, SES, comorbidity score, DMD prescription filled within 5 years), Fisher’s exact test for count data (DMD prescription filled by route of administration), and Wilcoxon rank sum test (age) were used to assess cohort characteristics (Table 1).

In order to analyse whether SES had a differential effect on DMD initiation between immigrants and long-term residents, we further included an interaction between SES and immigration status. We used a similar approach as in the main analyses, but with the quintiles as a continuous measure, and after excluding the minority (< 0.4%) of MS cases without an available SES.

Ethics, registration, and patient consents

This study was part of a wider research program registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04472975), and ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Boards at the University of British Columbia (#H18-00407; waiver for consent granted).

Data availability

As we are not the data custodians, we are not authorized to make the data available. With the appropriate approvals, the data may be accessed through the Population Data British Columbia.

References

Statistics Canada. Immigrants Make Up the Largest Share of the Population in Over 150 Years and Continue to Shape Who We are as Canadians. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221026/dq221026a-eng.htm (2022).

Wallin, M. T. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of multiple sclerosis 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 18, 269–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30443-5 (2019).

Lasser, K. E., Himmelstein, D. U. & Woolhandler, S. Access to care, health status, and health disparities in the United States and Canada: Results of a cross-national population-based survey. Am. J. Public Health 96, 1300–1307. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.059402 (2006).

Rotstein, D. L. et al. Health service utilization in immigrants with multiple sclerosis. PLoS ONE 15, e0234876. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234876 (2020).

Amezcua, L., Rivera, V. M., Vazquez, T. C., Baezconde-Garbanati, L. & Langer-Gould, A. Health disparities, inequities, and social determinants of health in multiple sclerosis and related disorders in the US: A review. JAMA Neurol. 78, 1515. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.3416 (2021).

Filippini, G. et al. Treatment with disease-modifying drugs for people with a first clinical attack suggestive of multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 4, CD012200. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012200.pub2 (2017).

Lebrun, C. et al. Impact of disease-modifying treatments in North African migrants with multiple sclerosis in France. Mult. Scler. 14, 933–939. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458508091369 (2008).

Berg-Hansen, P., Smestad, C., Sandvik, L., Harbo, H. F. & Celius, E. G. Increased disease severity in non-Western immigrants with multiple sclerosis in Oslo, Norway. Eur. J. Neurol. 20, 1546–1552. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.12227 (2013).

Martin, D. et al. Canada’s universal health-care system: Achieving its potential. Lancet 391, 1718–1735. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30181-8 (2018).

Baxter, N. N. Equal for whom? Addressing disparities in the Canadian medical system must become a national priority. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 177, 1522–1523. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.071578 (2007).

Tsai, P.-L. & Ghahari, S. Immigrants’ experience of health care access in Canada: A recent scoping review. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 25, 712–727. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-023-01461-w (2023).

Wang, L., Guruge, S. & Montana, G. Older immigrants’ access to primary health care in Canada: A scoping review. Can. J. Aging 38, 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980818000648 (2019).

Kalich, A., Heinemann, L. & Ghahari, S. A scoping review of immigrant experience of health care access barriers in Canada. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 18, 697–709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-015-0237-6 (2016).

Harding, K. E. et al. Socioeconomic status and disability progression in multiple sclerosis: A multinational study. Neurology 92, e1497–e1506. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000007190 (2019).

Calocer, F. et al. Low socioeconomic status was associated with a higher mortality risk in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 29, 466–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/13524585221129963 (2023).

Chandola, T., Ferrie, J., Sacker, A. & Marmot, M. Social inequalities in self reported health in early old age: Follow-up of prospective cohort study. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 334, 990. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39167.439792.55 (2007).

Uijen, A. A. & van de Lisdonk, E. H. Multimorbidity in primary care: Prevalence and trend over the last 20 years. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 14(Suppl 1), 28–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/13814780802436093 (2008).

Rotstein, D. et al. Risk of mortality in immigrants with multiple sclerosis in Ontario, Canada. Neuroepidemiology 54, 148–156. https://doi.org/10.1159/000506161 (2020).

Rotstein, D. L. et al. MS risk in immigrants in the McDonald era: A population-based study in Ontario, Canada. Neurology 93, e2203–e2215. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000008611 (2019).

Ng, H. S. et al. Disease-Modifying Drug Uptake and Health Service Use in the Ageing MS Population. Front. Immunol. 12, 794075. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.794075 (2022).

Ng, H. S. et al. Disease-modifying drugs for multiple sclerosis and association with survival. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 9, 5. https://doi.org/10.1212/NXI.0000000000200005 (2022).

British Columbia Ministry of Health [Creator] (2017): Medical Services Plan (MSP) Payment Information File. V2. Population Data BC [Publisher]. Data Extract. https://www.popdata.bc.ca/data/ (MOH, 2017).

Canadian Institute for Health Information [Creator] (2017): Discharge Abstract Database (Hospital Separations). V2. Population Data BC [Publisher]. Data Extract. https://www.popdata.bc.ca/data/ (MOH, 2017).

British Columbia Ministry of Health [Creator] (2017): PharmaNet. V2. BC Ministry of Health [Publisher]. Data Extract. https://www.popdata.bc.ca/data/ (Data Stewardship Committee, 2017).

Statistics Canada. Postal Code OM Conversion File (PCCF), Reference Guide. Catalogue No. 92-154-G. 2017. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/92-154-G (2021).

British Columbia Ministry of Health [Creator] (2017): Consolidation File (MSP Registration & Premium Billing). V2. Population Data BC [Publisher]. Data Extract. https://www.popdata.bc.ca/data/ (MOH, 2017)

BC Vital Statistics Agency [Creator] (2017): Vital Statistics Deaths. V2. Population Data BC [Publisher]. Data Extract. https://www.popdata.bc.ca/data/ (BC Vital Statistics Agency, 2017)

Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada [Creator] (2017): Permanent Resident Database. Population Data BC [Publisher]. Data Extract. https://www.popdata.bc.ca/data/ (IRCC, 2017).

Marrie, R. A., Yu, N., Blanchard, J., Leung, S. & Elliott, L. The rising prevalence and changing age distribution of multiple sclerosis in Manitoba. Neurology 74, 465–471. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cf6ec0 (2010).

Fereidan-Esfahani, M. et al. Population-based incidence and clinico-radiological characteristics of tumefactive demyelination in Olmsted County, Minnesota, United States. Eur. J. Neurol. 29, 782–789. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.15182 (2022).

Quan, H., Parsons, G. A. & Ghali, W. A. Validity of information on comorbidity derived from ICD-9-CCM administrative data. Med. Care 40, 675–685. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200208000-00007 (2002).

Disclaimer

Access to data provided by the Data Steward(s) is subject to approval, but can be requested for research projects through the Data Steward(s) or their designated service providers. All inferences, opinions, and conclusions drawn in this manuscript are those of the authors, and do not reflect the opinions or policies of the Data Steward(s).

Funding

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Project and Foundation Grant (PJT-156363 and FDN-159934, PI: HT). Jonas Graf receives a Research Fellowship from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Project Number 438899010, GZ: GR 5665/1-1). We are also grateful to Dr Lawrence W Svenson for supporting the team’s original funding application.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.G., Y.Z., and H.T. interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript. J.G., H.S.N., F.Z., J.M.A.W., C.E., J.D.F., R.A.M., Y.Z., and H.T. conceptualized and designed the study. J.G. (Research Fellowship from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft), as well as F.Z., C.E., J.D.F., R.A.M., Y.Z., and H.T. facilitated obtaining funding (PI: HT, CIHR Project and Foundation award). J.G., H.S.N., and F.Z. accessed the data and performed data analysis. All authors revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content, approved the final version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Jonas Graf has received in the last 3 years travel/meeting/accommodation reimbursements from Merck Serono, Sanofi-Genzyme, Grifols, and receives a Research Fellowship from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (project number 438899010, GZ: GR 5665/1-1). Huah Shin Ng has received funding from the MS Society of Canada’s endMS Postdoctoral Fellowship and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Trainee Award. John Fisk receives research funding from CIHR, the MS Canada, Crohn’s and Colitis Canada, Research Nova Scotia, the Nova Scotia Health Authority Research Fund, and licensing and distribution fees from MAPI Research Trust. Ruth Ann Marrie receives research funding from: CIHR, Research Manitoba, MS Canada, Multiple Sclerosis Scientific Foundation, Crohn’s and Colitis Canada, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, CMSC, the US Department of Defense, the Arthritis Society, Biogen Idec (no funds to her/her institution) and Roche (no funds to her/her institution), and is supported by the Waugh Family Chair in Multiple Sclerosis. Helen Tremlett has received research support in the last 3 years from the: Canada Research Chair program, National MS Society, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canada Foundation for Innovation, MS Society of Canada, the MS Scientific Research Foundation and the EDMUS Foundation (‘Fondation EDMUS contre la sclérose en plaques’). Feng Zhu, Yinshan Zhao, José M A Wijnands, and Charity Evans declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Graf, J., Ng, H.S., Zhu, F. et al. Multiple sclerosis disease-modifying drug use by immigrants: a real-world study. Sci Rep 13, 21235 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46313-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46313-7

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.