Abstract

Since many cities lack botanical gardens, we introduced the concept of Ancillary Botanic Gardens (ABG), which builds on the premise that organizations can expand informal botanical learning by adding a secondary function to their institutional green spaces. This study guides the application of the ABG concept in various spatial and functional contexts by offering practical and interpretive tools to organizations who are less used to working with nature but are interested in mitigating urban residents’ detachment from nature. Online maps of 220 botanic gardens were reviewed to define types of plant collections and produce an exhaustive list of physical botanic garden elements. The collected information was developed into an ABG field checklist that was tested on three case studies in Lebanon and then used to develop guidelines for ABG establishment. The guidelines and checklist are meant to empower and guide organizations interested in establishing an ABG.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In cities, absence of nature from everyday life leads to plant ‘blindness’, a ‘defective world view’, and contributes to detachment from, and destruction of, the natural world1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8.

Urban green spaces offer possibilities for residents to connect with nature especially in cities where there are limited possibilities to interact with the natural world. This opportunity to informally learn about plants and nature beyond schools and universities is described as “learner-motivated, guided by learner interests, voluntary, personal, and open-ended"9,10. However, exposure to plants in urban green spaces does not necessarily lead to an educational encounter. This is because many people are plant blind i.e., they tend to be unaware of plants and perceive them as lifeless, static, classified as ‘bulk categories’11, lost in the ‘chromatic homogeneity’, and harmless6. Plants are the ‘least understood and botanical learning is on the decline leading to an increasing gap in botanical knowledge and patchy and inconsistent conservation activities around the world2,12.

Botanic gardens are a type of green spaces that cater for informal botanical learning and for exchange between visitors and plants, evoking a sense of relationship to ecosystems and offering opportunities to explore complex questions about humans and their impact and relationship to other species13. When considering typologies of urban green spaces, botanic gardens fall at the center of a continuum, mediating between human experience normally offered by public parks and scientific understanding typically occurring is ecological restoration sites14.

However, the geographical distribution of botanic gardens in the world is skewed, and their contribution to informal botanical learning is limited globally. The number of botanic gardens is highest in Europe while most biodiverse areas, such as the tropics, have a small number of botanic gardens and countries in desert biomes, such as those of the Arab League, have the lowest number of botanic gardens15,16,17,18. Heywood19 highlighted this imbalance and showed that biodiversity rich countries have few botanic gardens and conservation activities. Westwood et al.20 called for a massive scale to create new gardens in biodiversity hotspots and low-income economy countries where conservation priority is the greatest.

Physical and financial limitations limit the possibility of a widespread increase in the number botanic gardens globally to mitigate plant blindness and mainstream conservation activities. Although there are several sources to guide the establishment of new botanic gardens or the upgrade of existing ones21,22,23,24,25, it is unlikely that countries struggling economically will dedicate land and resources in the city to set up and manage botanic gardens17. In fact, there is evidence that the persistence of current botanic gardens may be at stake. There are cases where urban development projects have taken over gardens in Kashmir and Iran, with Kashmir losing around 50% of its garden cover in the last decades26,27.

Transforming institutional green spaces in cities into botanic gardens is a solution proposed by Talhouk et al.17 to increase venues that offer informal botanical learning opportunities. The authors termed these Ancillary Botanic Gardens to emphasize the multifunctional use of urban green spaces, most of which were initially designed for aesthetic purposes. Talhouk et al.17 explained that, reconceiving urban green spaces physically and operationally as botanic gardens could offer similar educational roles. ABGs can “develop appropriate attitudes and behavior that may ultimately be responsible for saving the earth”28,29,30,31, allow visitors to “reflect of their evolving relationship with plants and the rest of the natural world”, and serve as places that will “continue to remind us of the many wonders of life here on earth”32,33. Talhouk et al.17 explained that Ancillary botanic gardens are secondary on a spatial level in that they are developed in green spaces of archaeological sites, public and private institutions, educational institutions, and touristic sites and institutions. A key aspect of ABGs is that unlike botanic gardens, both their role and scope are flexible rather than prescriptive and are not benchmarked against international standards22. This, however, should not lead to the conclusion that ABGs are ‘mere’ visits to green spaces because they are implemented following a locally driven mission to offer informal botanical learning.

Like urban botanic gardens, ABGs can offer informal botanical learning encounters and contribute to sustainability, and global conservation34. Depending on how and when they were set up, ABGs, like botanic gardens, can offer unique experiences of nature, telling a story about the culture or history of a community or geographic location35. They can use their premises holistically to raise awareness of environmental issues and conduct many activities that contribute to the achievement of the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals)16.

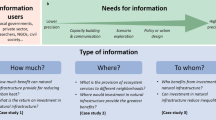

This paper examines the basic physical and functional elements of a botanic garden and argues that the application of the concept of Ancillary Botanic Garden is feasible, that when urban green spaces are conceived from this new perspective, they may expand informal botanical learning opportunities in cities. By proposing field assessment tools and universal ABG guidelines the authors propose a novel way to bring out the identity and value of plants in urban green spaces where they were placed as aesthetic backdrops to various institutions. The aim is to offer a road map for public and private institutions who are less used to working with nature to help mitigate urban residents’ detachment from nature. The ABG road map to guide the transformation of urban institutional green spaces into ABGs includes evidence-based tools that consist of guidelines, a field checklist, and a description of botanic garden elements. The tools developed by the study provide a common method, yet they offer interpretive flexibility guiding the transformation of urban institutional green spaces into ABGs in a variety of spatial and functional contexts.

Methods

The following flowchart depicts the various steps followed to develop the ABG guidelines (Fig. 1):

Defining elements characteristic of a botanic garden

The Garden Search database hosted by Botanic Garden Conservation International (BGCI), was used as the source for primary data collection and included, at the time the research was conducted, 3571 botanical institutions including botanic gardens, gene/seed banks, zoological institutions, private collections, and networks36. Characteristic elements of a botanic garden were found following a systematic analysis of 220 case study botanic gardens featured in the Garden Search global database (https://www.bgci.org/resources/bgci-databases/gardensearch/). Case study institutions included in the study were: botanic gardens (2907) that are members of the BGCI network (525) and have published a garden site plan online (260), which is narrated in English, French, or Arabic (220).

Data collection consisted of systematically inspecting the 220 botanic garden site plans and recording all marked elements in a spreadsheet, adding new entries for every newly encountered element. This iterative process of inspecting botanic garden maps and adding new entry fields to the spreadsheet continued until no new elements were found, and all botanic gardens with their elements shown on maps were accounted for (M. Melhem, and S.N. Talhouk conducted the content analysis and organized the elements into thematic categories without pre-existing frameworks).

Developing an Ancillary Botanic Garden checklist

The categorized botanic garden elements were organized into a matrix referred to as ABG field checklist and featuring columns that allow for comments on whether the element is present, absent, and comments on potential development of an element (matrix sheet not shown). The ABG field checklist was used for site analysis of cases study institutions.

Description of case study institutions

The case study institutions were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) the institution has a green space equal to or larger than the built area, (2) the owner is managing the green space, (3) the owner has expressed interest in exploring the possibility of retrofitting the green space into an ABG.

-

Case study 1 site primary function is the production of certified organic authentic Lebanese and Mediterranean juices, jams, and preserves. Located northeast of Beirut, the site building, land and old Mediterranean terraces were rehabilitated by the owner who is looking to reconstruct stories and traditions in memory of his grandfather.

-

Case study 2 is a residence in Beirut built in 1860. The estate is amongst the largest private homes in the city with a primary function to cater for weddings and exhibitions. The estate suffered extensive damage in the Beirut Blast in August 202037.

-

Case study 3 is a private school founded in 1873. The school is east of Beirut and its campus includes a wooded hillside with panoramic views.

Validating the Ancillary Botanic Garden checklist

Site visits were conducted by researchers to collect data using the ABG checklist in collaboration with the owner or assigned contact person who was present during the visits. The information compiled in the checklist included presence or absence of each element, description of its status, and suggestions for potential use or development of a botanic garden element.

Developing guidelines for retrofitting urban institutional green spaces into Ancillary Botanic Gardens

Opportunities and lessons learned from the three case studies constituted the basis for developing ABG guidelines.

Describing functionality, materiality, and modes of use of the recorded botanic gardens elements

To better guide and inform ABG stakeholders, each recorded botanic garden element was described as shown below:

A systematic Google Image search was conducted using the element as key word associated with the word ‘botanic garden’. When the search results produced unrelated images, a new search was performed using the element as the only key word. For each element, the top 20 image hits were examined, and the first five images that clearly showed physical aspects of the element, namely, material it is made of, its relative size, its context location, circulation related to it, types of activities within it, and accessibility to it, were selected. With the selected images, the following set of questions was addressed to complete the image guided description of each botanic garden element: What are the materials (soft scape, hardscape) used to construct the element? What is the estimated size of the element? Where is the element found? How is the circulation organized within or around the element? What do people do in the element? What is the main program of activities in the element? How is the element accessible? Is there any remarkable observation which was not included in the answers above?

Results

General description of case study botanic gardens

The case study botanic gardens (N = 220) are in Europe (36%), North America (26%), Asia (19%), Australia (11%), Africa (7%), and South America (1%) (Fig. 2). More than half (64%) of these botanic gardens are public, 20% are privately owned, and 16% are owned by academic/educational institutions.

The establishment dates of the case study botanic gardens span over 470 years. Using the five historical periods that coincide with changing roles of botanic gardens13,38, the results show that most case study botanic gardens were set up during the last two periods, i.e., between 1851 and 1960 and from 1960 till today (Table 1).

Typology of plant collections in case study botanic gardens

According to BGCI36, plant collections are organized as geographical—consisting of native plant collections from the surrounding region or national flora, taxonomic—displaying taxonomic plant groups, thematic—focusing on related or morphologically similar plants such as orchids and roses, or plants falling under the same theme such as medicinal plants, bonsai, and butterfly gardens, and ecological—including plants species that occur in similar habitats or ecotypes such as alpines or epiphytes36.

The number of recorded plant collections in the case study botanic gardens was 350, with some housing more than one collection, and less than half (45%) housing an arboretum. Based on the names assigned to the plant collections, it appears that half were thematic, one third were geographic, and less than 10% were ecological or taxonomic. Further inspection of the thematic plant collections names revealed a diversity of educational intents including habitats (ex: rock garden, moss garden, water garden), horticulture (ex: rose garden, vegetable, xeriscape), culture (ex: thirteenth century, Viking, Shakespeare, Memories), as well as leisure (ex: winter, shade, gravel, entry, exhibition) (Table 2).It is worth noting that the assignment of the collections under the four categories was based on the authors’ assessment of the name of the collection. There may have been overlaps between diverse types of collections that were overlooked such as geographical attributes which are also closely related with ecological and habitat attributes. This may affect the actual number of collections in each category but the fact that the largest numbers were those of thematic and geographic plant collections remains.

Botanic garden elements and thematic categories

Thirty-seven botanic garden elements were recorded and organized under seven themes namely, living collections, educational experiences, social experiences, natural experiences, cultural experiences, research and conservation, and water features (Table 3). In addition, there were 12 elements related to services and amenities. The percentage occurrence of each element in the case study botanic gardens was recorded. The highest-ranking elements present in more than 25% of botanic garden maps include plant collections, arboreta, and fauna (living collections), tours-trails and visitor education centers (educational experiences), restaurant-café, gift shop, and pavilion (social experiences), fauna, picnic, and children playground-trail (natural experience), herbarium and seedbank (research and conservation), and pond (water features). The highest-ranking elements under services and amenities included restrooms, parking, information desk, and wheelchair access.

Field testing of the Ancillary Botanic Garden checklist

For each case study institution, the Ancillary Botanic Garden checklist was completed during field visits as shown in Tables 4, 5, and 6, and Figs. 3, 4, and 5 below.

Guidelines for retrofitting institutional green spaces to Ancillary Botanic Gardens

This section elaborates general guidelines for Ancillary Botanic Gardens derived from the content analysis, field data observations, reflection about the applicability of the ABG concept following the receptivity of the stakeholders that took part in this exercise, and the authors experience in transforming the campus of the American University of Beirut into an Ancillary Botanic Garden40. The ABG guidelines shown below, along with the ABG checklist, and the description of each botanic garden element, are meant to inform and guide institutions interested in setting up an ABG on their premises to give benefit to the primary function of the institution (Table 7).

Discussion

Building on the concept of Ancillary Botanic Garden, this paper explored how reconceiving institutional urban green spaces could support informal botanical learning by emulating the layout and function of a botanic garden.

With over half its case study botanic gardens found in Europe and North America, the research first confirmed the reported imbalance in the geographic distribution of botanic gardens supporting the argument that many cities around the world lack these botanical institutions19. Addressing this skewed distribution, Westwood et al.20 called for a massive scale effort to create new gardens in biodiversity hotspots and low-income economy countries where conservation priority is the greatest and where prospects for global conservation efforts will be affected by the gap in botanical knowledge12. The outcome of this study, which guides public and private institutions on how to establish ABGs, is a response to calls for increasing botanic gardens worldwide. Furthermore, the proposed application of the ABG concept is innovative and sustainable and contributes to an increase in the number of botanic gardens that are locally grown, multifunctional, financially sustainable, and co-created with community41.

To better understand the nature of plant collections typically housed in botanic gardens, the study explored the types of plant collections ‘worthy’ of imparting informal botanical learning in the case study botanic gardens. The findings revealed that most plant collections have a geographic or thematic scope rather than an ecological or taxonomic one. This may be because many of these gardens were set up during periods where the focus was on public education and horticulture rather than research38,39. This finding is important in that it points to the fact that a scientific underpinning is not necessary to offer informal botanical learning to the public. In fact, many institutions have developed botanical collections within their institutional grounds to cater for the learning of their constituencies. Schools have set up botanical collections to offer students dynamic and novel educational methods, boost students’ consumption of fruits and vegetables, and instill an early determination for environmental conservation42,43,44. Universities display native and traditionally used plant species on their campuses to promote local heritage and culture. Medical institutions have set up therapy and edible plant gardens to promote well-being45. Civil society groups transformed public green spaces into botanic gardens to provide communities with a sense of place ownership, to promote wellbeing, and to serve as a link to traditional knowledge46,47. In this research, field assessment of the first case study site revealed that it houses two types of plant collections namely; a Mediterranean-terrace habitat plant collection, and traditional horticultural varieties. The second case study site has a collection of trees and shrubs representative of historic Beirut gardens. The third case study includes a Mediterranean pine woodland habitat. Although all three case study institutions selected plant species with no educational goal in sight, today, these plant collections can contribute to local informal botanical learning. The ABG field checklist and guidelines guide the process of defining the theme of the plant collections in each urban green space depending on the predominance of the species present at the time of the ABG field assessment. Considering that, each urban institution set up its urban green space independently and at various times, when many such institutions engage in this transformation of their green spaces into ABGs, they will offer diverse scale, size, and scope for informal botanical learning through their plant collections. They will also ‘casually’ reach out to a larger number of citizens by targeting their respective constituencies.

Unlike the focus of the literature on the design and establishment of new botanic gardens, this study contributes to grassroots action by offering urban institutions, who may wish to contribute to informal botanic learning, tools that aid in assigning a secondary function to green spaces without jeopardizing their institutional primary function. The importance of botanic gardens as providers of education and recreation is well established48,49; and has driven the production of many publications to guide the establishment of new botanic gardens or upgrade of existing ones21,22,23,24,25. The tools provided in this study are especially relevant in poor countries and in line with Reid and Gable50 who suggested that small-scale horticultural oases such as localized community, school, and demonstration gardens can play the same educational role as botanic gardens and can have multiplied impacts that also include building a sense of community underserved areas.

Regarding the type of institutions that can engage in the establishment of ABGs, the study revealed that more than half of the case study botanic gardens are public, 20% privately owned, and 16% owned by academic/educational institutions. Although the findings of the content analysis suggest an important opportunity to reconceive public green spaces into ABGs, the case study locations in this research were drawn from privately owned green spaces. We do not believe that there is a particular situation in Lebanon that makes private gardens / institutions more prone to be transformed into ABG. However, during the research, it was not possible to secure a case study location standing for a public green space due to political conflicts and economic instability, which left public institutions idle and dysfunctional with limited financial and human resources. On the other hand, Talhouk et al.51 showed unique opportunities to expand the scope and breadth of botanical learning in Lebanon by reconceiving public green spaces, specifically the peripheries of archeological sites, which are around 350 and vary from three to 25 hectares, as ABGs. Work is in progress to develop one of these sites as an ABG in collaboration with the Lebanese Ministry of Culture. Efforts are also ongoing to explore green space assets of tourism resorts to contribute to informal botanical learning. By establishing ABGs, public and private institutions may develop a new and different relation with their constituencies, residents, staff, or clients, by sharing a physical green space that promotes the supportive role of nature and by encouraging them to revisit the relationship between plants and people and plants and local cultures13.

The botanical garden elements shown after a content analysis of the 220-case study were organized into themes and developed into an ABG field checklist used in field assessments. The checklist allowed for a systematic recording and evaluation on site of each element during field visits, deciding whether the element was present or absent. More importantly, systematically going over the checklist gave the opportunity to co-design with the owners the physical and operational opportunities to develop a given botanic garden element and associated activities. The findings and suggestions arising from this exercise are listed in Tables 4, 5, and 6. This approach is important as it guides a systematic assessment that precedes the transformation of the green space into an ABG while observing locality, i.e., a botanic garden that is locally grown, multifunctional, financially sustainable, and co-created with community41.

An important contribution of the ABG field checklist was unveiled during field evaluations of the case study sites. The systematic assessment of the presence, absence, or potential development of an element following clear theme related to experiences in botanic gardens built the confidence of stakeholders in the possibility of contributing to informal botanical learning. Stakeholders saw clarity in the assessment and planning of an ABG which was physically and operationally aligned with formal botanic gardens. Field assessments using the ABG field checklist also opened new perspectives for owners of how their green spaces are seen, and used, and how the institution’s history and culture can be part of it. For example, stakeholders of the case study sites were not aware of the value of their plant collections. The field checklist dispelled the misconception amongst stakeholders that plants with educational value are specific to botanic gardens. Maunder52 and Robertson4 showed that botanic gardens have been judged, or have judged themselves, by the number of species held in the garden; however, the value of plant collections is in their contribution to economic and social development rather than by the number of the species kept as botanical living dead. Furthermore, Rae53 pointed out that it is not uncommon that botanic gardens build up their collection first and then afterwards sort out the justification of the existence of their collections.

The ABG guidelines presented in this study are an application of the ABG concept and were informed by insights gained from the content analysis, the development of the ABG checklist and its field application. While content analysis helped list the basic elements and types of operations in a botanic garden, the use of the ABG checklist during field assessments showed which elements are unlikely to be found in institutional urban green spaces. These elements were kept in the field checklist, but not included as core elements in the guidelines. With respect to living collections, the ABG guidelines were also informed by the field visits to case study sites where it was clear that a holistic view of the vegetation, i.e., landscape of the site including the history of the institution may be an inspiration for naming the living collection. The field visits also highlighted the importance of collaboration between stakeholders within the institution and outside the institution to lead and sustain activities in the ABG. Another element clear from the field visit is that the commitment of an institution to setting up an ABG reflects its commitment to conservation and community engagement, and this commitment should be communicated.

The ABG guidelines are universal in scope, beyond Lebanon, and applicable in various spatial and functional contexts. More importantly, the guidelines incorporate key aspects of the ABG concept17. Unlike botanic gardens, ABGs are ‘deregulated’ and seek to promote informal botanical learning, their roles and scope are not benchmarked against international standards22, and their mandates are flexible rather than prescriptive and are defined by stakeholders. This does not mean that ABGs are designed as ‘mere’ urban green spaces because they are conceived to offer botanical learning hence the importance of the ABG guidelines, the field checklist, and the description of the elements. Based on physical and operational elements of formal botanic gardens, the ABG guidelines capture the essence of the ABG concept as follows: They rely on local nomenclature which is fundamental in developing enthusiasm for plant conservation, they seek to create themes from existing plant assemblages, essential for effective local communication and engagement, they encourage the engagement of taxonomically illiterate members of society as ‘custodians’ of ethnobotanical knowledge, they guide the development of urban green spaces as local ‘nature’ that is healing for adults, a free play space for children, and wildlife friendly for biodiversity, they link the institution’s culture and history with nature and culture, and they encourage the development of inclusive greenspaces.

With the ABG checklist and the description of the botanic garden elements, the guidelines are the ABG concept’s application. They offer practical and interpretive tools to organizations who are less used to working with nature but are interested in mitigating plant blindness and urban residents’ detachment from nature.

Conclusion

By exploring the application of the Ancillary Botanic Garden concept, this study has contributed to the mitigation of plant blindness by developing guidelines that guide the repurposing of urban green spaces to bring out the educational value of plants. Based on an analysis of formal botanic gardens, the guidelines, along with the field checklist, and description of elements, are also an example of how to promote collaboration between public and private institutions. On a practical level, the developed tools offer benefits to visitors, allowing regular access to urban green spaces and botanical learning opportunities. They also allow institutions to maximize the use of an underutilized asset and formalize their contribution to nature and human wellbeing. Finally, it is worth noting that one of the case study sites registered as a formal botanic garden following this research, showing that ABGs may be a transitioning step by urban institutions who chose to further commit to botanical learning and join the global botanic garden community by becoming a member of formal botanic garden organizations.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cox, D. T., Hudson, H. L., Shanahan, D. F., Fuller, R. A. & Gaston, K. J. The rarity of direct experiences of nature in an urban population. Landsc. Urban Plan. 160, 79–84 (2017).

Cronquist, A. Plantwatching How plants remember, tell time, form partnerships and more. By Malcolm Wilkins. Brittonia 40, 356 (1988).

Lehmann, S. Reconnecting with nature: Developing urban spaces in the age of climate change. Emerald Open Res. 1, 2 (2019).

Robertson S. A. Flora of Aride Island Seychelles. 209–210 (1996)

UNFPA. Annual Report 2016 in 2017 (Accessed February 10, 2019); https://www.unfpa.org/annual-report-2016

Wandersee, J. H. & Schussler, E. E. Preventing plant blindness. Am. Biol. Teach. 61(2), 82–86 (1999).

Williams, S. J., Jones, J. P., Gibbons, J. M. & Clubbe, C. Botanic gardens can positively influence visitors’ environmental attitudes. Biodivers. Conserv. 24(7), 1609–1620 (2015).

Worpole, K. Regaining an interior world. Landsc. Design 289, 20–22 (2000).

Bell, P., Lewenstein, B., Shouse, A. & Feder, M. Learning Science in Informal Environments: People, Places, and Pursuits (National Research Council, 2009).

Freeland, E. The role of informal environmental education in the changing political climate of 2017 in the USA: A focus on climate change.

Zakia, R. D. Perception and Imaging: Photography–A Way of Seeing (Taylor & Francis, 2013).

Sharrock, S. & Chavez, M. The role of Botanic Gardens in building capacity for plant conservation. BG J. 10(1), 3–7 (2013).

Sanders, D. L., Ryken, A. E. & Stewart, K. Navigating nature culture and education in contemporary botanic gardens. Environ. Educ. Res. 24(8), 1077–1084 (2018).

Hohn, T.C. Curatorial practices for botanicalgardens. Lanham: Rowman Altamira. Martinelli, G.& Moraes, M.A. (Org.). 2013. Livro Vermelho da Flora do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Andrea JakobssonEstúdio (2008).

Antonelli, A. et al. An engine for global plant diversity: Highest evolutionary turnover and emigration in the American tropics. Front. Genet. 6, 130. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2015.00130 (2015).

O’Donnell, K. & Sharrock, S. The contribution of botanic gardens to ex situ conservation through seed banking. Plant Divers. 39(6), 373–378 (2017).

Talhouk, S., Abunnasr, Y., Hall, M., Miller, T. & Seif, A. Ancillary Botanic Gardens in Lebanon: Empowering local contributions to plant conservation. Sibbaldia Int. J. Botanic Garden Horticult. https://doi.org/10.24823/Sibbaldia.2014.27 (2014).

UNEP-WCMC. The State of Biodiversity in Africa: A mid-term review of progress towards the Aichi Biodiversity Targets. UNEP-WCMC Cambridge UK (2016).

Heywood, V. H. The future of plant conservation and the role of botanic gardens. Plant Divers. 39(6), 309 (2017).

Westwood, M., Cavender, N., Meyer, A. & Smith, P. Botanic garden solutions to the plant extinction crisis. Plants People Planet 3(1), 22–32 (2021).

Borsch, T. & Löhne, C. Botanic gardens for the future: Integrating research conservation environmental education and public recreation. Ethiopian J. Biol. Sci. 13, 115–133 (2014).

Gratzfeld J. (Ed.). From idea to realisation – BGCI’s manual on planning, developing and managing Botanic Gardens. Botanic Gardens Conservation International Richmond United Kingdom (2016).

Kneebone S. & Willison J. A global snapshot of botanic garden education provision. 3rd Global Botanic Gardens Congress BGCI (pp. 15–20) (2007).

Reid, A. Environmental education research-milestones and celebrations. Environ. Educ. Res. 25(1), 1–5 (2019).

Volis, S. Conservation utility of botanic garden living collections: Setting a strategy and appropriate methodology. Plant Divers. 39(6), 365–372 (2017).

Ershad A. By night Iran’s urban gardens are disappearing. France24 in 2017: https://observers.france24.com/en/20170315-night-iran%E2%80%99-urban-gardens-are-disappearing

Kaul G. Disappearing gardens: In response to a GK story on the decline of garden cover in Srinagar in 2021. (Greater Kashmir); https://www.greaterkashmir.com/todays-paper/disappearing-gardens

Byrd, W. T. J. Re-creation to recreation: The botanic garden as arboreal ark. Landscape Architecture 79, 42–51 (1989).

Houston, C. C. Conservation design guidelines for botanic gardens. Graduate Theses and Dissertations, 529 (2009).

Smith, A. ‘Botanic gardens - what can they teach?’ Roots, 2, 8. students’ botanical sense of place. Am. Biol. Teach. 68(7), 419–422 (1990).

Wyse Jackson, P. S. Experimentation on a large scale–an analysis of the holdings and resources of botanic gardens. Botanic Gard. Conserv. News 3(3), 27–30 (1999).

Johnson, B. & Medbury, S. Botanic Gardens: A living history (Black Dog Publishing, 2007).

Sanders, D. Building sustainable botanic gardens: Beyond architecture. In Proceedings of the 4th Global Botanic Gardens Congress. p. 1 (2010).

Zelenika, I., Moreau, T., Lane, O. & Zhao, J. Sustainability education in a botanical garden promotes environmental knowledge attitudes and willingness to act. Environ. Educ. Res. 24(11), 1581–1596 (2018).

Paiva, P. D. D. O., Sousa, R. D. B. & Carcaud, N. Flowers and gardens on the context and tourism potential. Ornamental Hortic. 26, 121–133 (2020).

BGCI. Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Richmond U.K: 2019. Garden Search Online Database. Available at: https://www.bgci.org/resources/living_collections

John T., et al. Beirut explosion rocks Lebanon's capital city in 2020. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/middleeast/live-news/lebanon-beirut-explosion-live-updates-dle-intl/h_e062fcb57b659cf33da424f059e4ca2b

Heywood V. H. The changing role of botanic gardens. Proceedings of an International Conference Botanic Gardens and the World Conservation Strategy 3–18 (1987).

Mielcarek L. E. Factors associated with the development and implementation of master plans for Botanical Gardens. The University of Arizona United States (2000).

Talhouk, S. N., Abi, A. R., Forrest, A. & Abunnasr, Y. Ancillary Botanic Gardens: A case study of the American University of Beirut. Pullaiah, T. and A. Galbraith. Botanical Gardens and Their Role in Plant Conservation: Asian Botanical Gardens (David Taylor & Francis Ltd., 2023).

Dushkova, D. & Haase, D. Not simply green: Nature-based solutions as a concept and practical approach for sustainability studies and planning agendas in cities. Land. 9, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9010019 (2020).

Berezowitz, C. K., Bontrager Yoder, A. B. & Schoeller, D. A. School gardens enhance academic performance and dietary outcomes in children. J. Sch. Health. 85(8), 508–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12278 (2015).

Sanders, D. L. Making public the private life of plants: The contribution of informal learning environments. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 29(10), 1209–1228 (2007).

Sellmann, D. & Bogner, F. X. Climate change education: Quantitatively assessing the impact of a botanical garden as an informal learning environment. Environ. Educ. Res. 19(4), 415–429 (2013).

Stagg, B. C. & Donkin, M. Teaching botanical identification to adults: Experiences of the UK participatory science project ‘Open Air Laboratories’. J. Biol. Educ. 47(2), 104–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2013.764341 (2013).

Graham, H., Beall, D. L., Lussier, M., McLaughlin, P. & Zidenberg-Cherr, S. Use of school gardens in academic instruction. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 37(3), 147–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60269-8 (2005).

Mazin, Q. et al. Role of museums and botanical gardens in ecosystem services in developing countries: Case study and outlook. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 74, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207233.2017.1284383 (2017).

Dodd, J. & Jones, C. Towards a new social purpose: The role of botanic gardens in the 21st century. Roots (Bot Gard Conserv Int Edu Rev) 8, 5–8 (2011).

Kohlleppel, T., Bradley, J. C. & Jacob, S. A walk through the garden: Can a visit to a botanic garden reduce stress?. Hort Technol. 12(3), 489–492 (2002).

Reid K. & Gable M. University-trained volunteers use demonstration gardens as tools for effective and transformative community education. In I International Symposium on Botanical Gardens and Landscapes 1298. p. 85–90. (2019)

Talhouk, S. N., Abunnasr, Y., Forrest, A. & Miller, T. Ancillary botanic gardens. In Conserving Wild Plants in the South and East Mediterranean Region (eds Valderrábano, M. et al.) (IUCN, 2018).

Maunder, M. Botanic gardens: Future challenges and responsibilities. Biodivers. Conserv. 3(2), 97–103 (1994).

Rae D. A. Botanic gardens and their live plant collections: present and future roles (Doctoral dissertation) (1995).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the case study institutions for their willingness and interest in supporting research and botanical learning

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.N.T developed the ABG concept; Y.A. and A.F. contributed to the elaboration of the ABG concept; M.M. conducted the desk and field research; S.N.T. supervised and guided the desk and field research; R.A. assisted in the revision of the data; M.M. wrote a draft of the manuscript; S.N.T. made extensive revisions to the draft and rewrote the discussion; Y.A. and A.F. reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Melhem, M., Forrest, A., Abunnasr, Y. et al. How to transform urban institutional green spaces into Ancillary Botanic Gardens to expand informal botanical learning opportunities in cities. Sci Rep 13, 15646 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41398-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41398-6

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.