Abstract

Nocturia is a manifestation of systemic diseases, in which chronic kidney disease (CKD) is an independent predictor of nocturia due to its osmotic diuretic mechanism. However, to our knowledge, previous studies have not examined the association between nocturia and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). The purpose of this study was to assess the association between nocturia exposure and eGFR in the general US population. This study presents a cross-sectional analysis of the general US population enrolled in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 2005 to 2018. To account for potential confounding factors, linear regression analysis was conducted to investigate the association between nocturia and eGFR. Stratified analyses and interaction tests were employed to examine the variables of interest. Additionally, sensitivity analyses were conducted across diverse populations. A total of 12,265 individuals were included in the study. After controlling for confounding factors, the results of the linear regression analysis indicated that a single increase in nocturnal voiding frequency was associated with a decrease in eGFR by 2.0 mL/min/1.73 m2. In comparison to individuals with a nocturnal urinary frequency of 0, those who voided 1, 2, 3, 4, and ≥ 5 times at night experienced a decrease in eGFR by 3.1, 5.4, 6.4, 8.6 and 4.0 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively. Nocturia was found to be associated with a decreased eGFR of 4 mL/min/1.73 m2 when compared to individuals without nocturia. The sensitivity analysis yielded consistent findings regarding the association between nocturia and eGFR in both CKD and non-CKD populations, as well as in hypertensive and non-hypertensive populations. Nevertheless, inconsistent conclusions were observed across various prognostic risk populations within the CKD context. The presence of nocturia and heightened frequency of nocturnal urination have been found to be associated with a decline in eGFR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

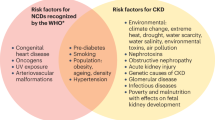

Nocturia, as per the definition provided by the International Continence Society (ICS), refers to the frequency of urination episodes experienced during the main sleep period. It is essential that after the initial awakening for urination, each subsequent urination episode is accompanied by either sleep or the intention to sleep1. Nocturia can arise from various etiologies, such as diminished bladder capacity, sleep disorders, and nocturnal polyuria2,3,4. The prevalence of nocturia among adults is notably high, but it tends to be underestimated by both patients and physicians5. The implications of nocturia can be severe, encompassing insomnia, debilitation, urinary incontinence, and falls6. Moreover, heightened severity of nocturia is linked to a decline in quality of life7. Furthermore, nocturia is correlated with an elevated probability of experiencing depressive symptoms8,9. Furthermore, there exists a significant correlation between cardiovascular disease and the prevalence of nocturia10. Research has demonstrated that the manifestation of nocturia serves as an initial indication of CKD and arises from a compromised capacity to concentrate urine11.

Based on a review of previous research, the association between the frequency of nocturnal urination and eGFR remains inconclusive. A study12 reported a significant association between CKD and the severity of nocturia. Furthermore, the findings of Minhang et al.13 indicated that higher eGFR was less likely to be linked with nocturia (odds ratio < 1). In a study conducted by Xuke et al.14, it was observed that patients with CKD exhibited significantly elevated nocturia score. Furthermore, the study identified lower eGFR and overweight as independent risk factors for nocturia. However, in a cross-sectional study15 involving 861 older adults residing in the community, no significant correlation was observed between nocturia and decreased eGFR when defining nocturia as two or more nocturnal urination. Considering the lack of clarity regarding the relationship between nocturnal urination frequency and eGFR, further investigation into their association is deemed imperative.

Methods

Study population

The present study utilized data from the NHANES spanning the years 2005 to 2018. This dataset provided valuable information pertaining to the frequency of nocturnal urination, the presence of prostate enlargement, and renal outcomes. Our investigation specifically focused on nocturnal urination frequency, eGFR, and urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (UACR). Supplementary Fig. 1 displays the flowchart illustrating the study design. Participants were included in the analysis only if they had complete data on all variables, including race/ethnicity, gender, age, fasting blood glucose, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TCHOL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low density lipoprotein (LDL), uric acid, eGFR, creatinine (Cr), UACR, body mass index (BMI), previous medical history (hypertension, diabetes), history of smoking and alcohol consumption and psychological factor (item patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)). It is important to highlight that individuals with prostate enlargement were deliberately excluded from the study. The absence of ethical review was justified by the fact that all data used in the study were publicly accessible and fully anonymized. This report adheres to the reporting guidelines for cross-sectional studies outlined in the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)16.

Measurement and definition of nocturia

Each participant’s nocturia data was obtained from the NHANES questionnaire on “During the past 30 days, how many times per night did you most typically get up to urinate, from the time you went to bed at night until the time you got up in the morning”. Following the guidelines set by the ICS, participants who reported urinating at least once during the night were diagnosed with nocturia.

Measurement of eGFR

The eGFR measurement is not readily accessible within the NHANES database. Consequently, the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology(CKD-EPI) equation, as developed by Levey17, was employed to estimate eGFR. Levey17 synthesized data from 10 studies to establish the CKD-EPI formula, which allows for the estimation of serum creatinine GFR. The formula underwent validation through data from 16 studies, demonstrating enhanced accuracy and reduced bias, particularly in the calculation of eGFR ≥ 60 mg/min.

Covariates

NHANES collected data regarding the age, sex, and race (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Mexican American, and other) of participants. During the physical examination phase of the survey, measurements of height, weight, and blood pressure were obtained. Medical professionals collected blood and urine samples, which were subsequently sent to the testing facility. The study also gathered the following covariates: fasting blood glucose, HbA1c, biochemical markers (ALT, AST, Cr and uric acid), lipids (TG, TCHOL, LDL and HDL), UACR, PHQ-9 score, past medical history (hypertension and diabetes) and history of smoking and alcohol consumption.

The BMI was determined by dividing the measured weight in kilograms by the measured height in meters squared18. This resulted in a categorical classification of BMI, with underweight defined as BMI < 18.5, normal weight as 18.5 ≤ BMI < 25, overweight as 25 ≤ BMI < 30, and obese as BMI ≥ 30.

Hypertension was determined based on the criteria of having a systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg, or a diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg, measured on three consecutive occasions. Additionally, it encompassed individuals who were prescribed medication for hypertension or had received a professional diagnosis from a doctor or other healthcare provider. diabetes, on the other hand, was diagnosed when a physician informed the participant of their condition and prescribed hypoglycemic medication for the regulation of blood glucose levels.

Extract answers to the following questions: “In the past 12 months, on those days that you drank alcoholic beverages, on the average, how many drinks did you have?” and “Days have 5 or more drinks/past 12 month” and “Days per week, month, year?” and “Had at least 12 alcohol drinks/lifetime?”. Drinking severity was defined19 as (1) heavy alcohol user: ≥ 3 drinks per day for female, ≥ 4 drinks per day for male, binge drinking on 5 or more days per month. (2) moderate alcohol user: ≥ 2 drinks per day for female, ≥ 3 drinks per day for male, binge drinking ≥ 2 days per month. (3) mild alcohol user: ≥ 1 drinks per day for female, ≥ 2 drinks per day for male. (4) non-drinking was defined as answering no to the question “Had at least 12 alcohol drinks/lifetime?”.

Smoking is defined as answering “yes” to the following questions “Smoked at least 100 cigarettes in life?”. Or answer “every day” or “some days” to the question “Do you now smoke cigarettes?”. Otherwise, is defined as non-smoking.

In this study, the assessment of depressive symptoms was carried out utilizing the PHQ-9, a tool comprising nine items derived from the symptoms of depression outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV)20. For the purposes of this study, depressions deemed clinically significant were defined as those with PHQ-9 total score equal to or exceeding 1021.

Statistical analysis

The principle of weighting served as the “lowest common denominator”. In this study, NHANES provided weights for fasting blood glucose samples, which were then combined with weights from all 8 cycles and followed NHANES guidelines for analysis. Linear regression analysis was employed to ascertain the association between frequency of nocturnal urination and eGFR. The ultimate model incorporates adjustments for significant confounding variables, which are determined by observing changes in effect estimates of more than 10% or regression coefficients of covariates with p-values below 0.1. A stratified analysis was conducted to examine the impact of nocturnal urination frequency on the continuous variable of eGFR. Additionally, stratified analyses and interaction tests were conducted for each covariate to assess their influence on the association between nocturnal urination frequency and eGFR. Finally, sensitivity analyses were conducted in diverse populations to ensure the robustness of the findings. The statistical software programs R (version 4.2.0) and Empower Stats (version 4.0) were employed to conduct all the analyses. Statistical significance was evaluated utilizing a two-sided significance level of 0.05.

Results

Supplementary Table 1 presents demographic information and descriptive statistics related to nocturnal urination frequency for the 12,265 NHANES individuals who participated in this study. In addition, Table 1 presents weighted demographic information and descriptive statistics related to frequency of nocturnal urination. Among these individuals, the highest number of individuals reported urinating once at night. Briefly, the number of individuals with no nocturnal urination, as well as those with 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 or more episodes of nocturnal urination was 3720, 4705, 2301, 979, 327 and 233, respectively. Furthermore, the majority of the study population included individuals with CKD stages 1 and 2. In comparison to individuals who experienced voided 0-time or 1-time during night, experienced voided 2 or more times exhibited elevated levels of age, fasting blood glucose, HbA1C, ALT, TG, HDL, BMI, and UACR. Conversely, individuals with a higher frequency of nighttime urination demonstrated a lower eGFR. Additionally, an escalation in the frequency of nocturia was associated with an increased prevalence of smoking, drinking, hypertension, diabetes, CKD, and depression. In populations exhibiting varying prognostic risks for CKD, a notable rise in the percentage of individuals experiencing voiding more than three times at night was observed with in the very high risk, high risk and moderate risk groups. Nevertheless, no statistically significant differences were found in the levels of AST, uric acid, TCHOL, and LDL across different frequency groups of nocturnal urination (P > 0.05).

Nocturia is associated with a decrease in eGFR

The initial examination focused on the association between the gathered covariates and eGFR, as presented in supplement Table 2. Univariate analysis demonstrated a significant association between age, elevated fasting blood glucose, HbA1c, uric acid, lipids, BMI, and increased frequency of nocturnal urination with a decline in eGFR. Furthermore, smoking, hypertension, and diabetes were also found to be associated with a decrease in eGFR. These findings align with previous research studies22,23,24,25. This study examines the potential use of the PHQ-9 score as a diagnostic tool for depression, considering the established relationship between depressive symptoms and the risk of rapid decline in eGFR, end-stage renal disease and acute kidney injury26. Furthermore, it acknowledges the documented association between nocturia and increased likelihood of depression8,9,27. However, it is important to note that this study did not observe a significant association between depression and eGFR.

To evaluate the independent impact of nocturia on eGFR, we defined nocturia as the occurrence of nocturnal urination at least once. As indicated in Table 2, nocturia was found to be significantly associated with a reduction of 7.3 ml/min/1.73 m2 in eGFR when compared to individuals without nocturia, without any adjustments for confounding variables. In model II, after adjusting for important covariates such as CKD, CKD prognosis risk, fasting blood glucose, HbA1c, ALT, AST, Cr, uric acid, TG, HDL, drinking habits, smoking status, hypertension, BMI, and PHQ-9 score, linear regression analysis revealed that nocturia was still associated with a decrease of 4.0 ml/min/1.73 m2 in eGFR compared to individuals without nocturia.

Furthermore, in order to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the independent impact of nocturnal urination frequency on eGFR, we employed measures to control for potential confounding variables and conducted a linear regression analysis as presented in Table 2. Our findings indicate that a single increase in the frequency of nocturnal urination is associated with a decrease in eGFR by 3.5 mL/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI − 3.9, − 3.1) when not accounting for other confounders. However, after adjusting for these confounding factors, we observed that a one-time increase in nocturnal urination frequency is linked to a reduction in eGFR by 2.0 mL/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI − 2.2, − 1.7).

Subsequently, in order to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the association between nocturnal urinary frequency and eGFR, we conducted an analysis of nocturnal urinary frequency using categorical variables. In the absence of any adjustments for variables, our findings indicate that the population with a frequency of one nocturnal urination experienced a decrease in eGFR of 5.5 mL/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI − 6.4, − 4.6) in comparison to those with no nocturnal urination. Similarly, individuals who voided 2, 3, 4, and ≥ 5 times during the night exhibited a decrease in eGFR of 9.3 mL/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI − 10.5, − 8.2), 11.4 mL/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI − 13.1, − 9.7), 13.0 mL/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI − 16.0, − 10.0), and 9.9 mL/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI − 13.3, − 6.4), respectively. Furthermore, following adjustment for various confounding variables, our analysis revealed a significant decline in eGFR of 3.1 mL/min/1.73 m2 among individuals who voided once during the nocturnal period, as compared to those who did not void at all. Moreover, we observed a progressive decrease in eGFR of 5.4 mL/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI − 6.2, − 4.6), 6.4 mL/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI − 7.6, − 5.3), 8.6 mL/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI − 10.6, − 6.5), and 4.0 mL/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI − 6.3, − 1.7) for individuals who voided 2, 3, 4 and ≥ 5 times during the nocturnal period, respectively.

Investigation of the association between nocturia and eGFR in different populations

According to the criteria established by Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO)28, the population was divided into two groups: those with CKD and those without CKD. This division was based on an eGFR of less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and a UACR of 30 mg/g or higher. The eGFR and UACR were used to assess the prognostic risk of CKD in the participants. In order to determine the factors that influenced the impact of nocturnal urination frequency on eGFR, we examined the interaction of various confounding variables. Our analysis revealed a significant interaction between the frequency of nocturnal urination and hypertensive status, CKD status, and CKD prognostic risk (interaction P = 0.0497, 0.029, 0.0005, respectively) (see supplement Table 3). Consequently, a stratified analysis was conducted on various populations affected by CKD, populations with hypertension, and populations at risk for CKD prognosis. Figure 1 demonstrates a consistent association between eGFR and nocturia as well as nocturnal urination frequency in both CKD and non-CKD populations. Likewise, this association remained consistent in populations with and without hypertension, as depicted in Fig. 2. Furthermore, Fig. 3 reveals disparate findings among different prognostic risk populations for CKD. Our study revealed a significant correlation between the frequency of nocturia/nocturnal urination and a decline in eGFR among individuals classified as intermediate risk and low risk. However, no such association was observed in the very high risk and high risk groups.

Discussion

In a comprehensive analysis of adult US citizens utilizing the NHANES database, an association was observed between nocturia/heightened frequency of nocturnal urination and diminished eGFR. This study stands as the most extensive investigation to date, demonstrating the presence of such a correlation within the American population. The outcomes align with a pathophysiological mechanism of nocturia, thereby indicating that it may serve as an indicator of renal disease29,30,31. Several early studies32,33 have investigated the etiology of nocturia, yet there has been a limited emphasis on exploring the correlation between nocturia and renal function. Historically, nocturia has been regarded as an inconsequential phenomenon, resulting in a scarcity of patients seeking medical intervention due to perceiving it as a natural consequence of aging34. Our research findings serve as a compelling alert to both physicians and patients, highlighting the association between nocturia and reduced eGFR. Consequently, this serves as a reminder to healthcare professionals to exercise vigilance regarding alterations in renal function when confronted with patients presenting with nocturia.

Our study revealed that, after accounting for confounding variables, the outcomes of the linear regression analysis demonstrated that a single increase in nocturnal voiding frequency resulted in a decrease of 2.0 mL/min/1.73 m2 in eGFR. In comparison to individuals with a nocturnal urinary frequency of 0, those who voided 1, 2, 3, 4, and ≥ 5 times during the night experienced a decrease in eGFR of 3.1, 5.4, 6.4, 8.6 and 4.0 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively. Nocturia was found to be associated with a decrease in eGFR of 4.0 mL/min/1.73 m2 when compared to individuals without nocturia. These findings suggest a correlation between nocturia, increased frequency of nocturnal urination, and lower eGFR. There is compelling evidence indicating a strong correlation between nocturia and renal function. Empirical findings suggest that nocturia emerges as an early indicator of CKD when renal function declines, leading to a reduced ability to concentrate urine. Certain researchers propose that osmotic diuresis, rather than free-water diuresis, is responsible for plays a role in nocturia and impaired renal function in CKD11,32. In addition, in individuals with CKD, nocturia, may serve as a potential marker for diminished renal tubular function35. While prior research has demonstrated a connection between nocturia and renal function, our study represents the inaugural investigation into the correlation between nocturia and eGFR. Consequently, this finding serves as a valuable prompt for clinicians to be attentive to patients who report experiencing one or more episodes of nocturnal urination per night.

Numerous diseases have been found to be linked with the occurrence of nocturia. Research has demonstrated a significant 39% rise in the prevalence of nocturia among individuals classified as obese, with a BMI over 30 kg/m2, in comparison to those who are non-obese36. Subsequently, individuals diagnosed with diabetes were found to have a 49% higher likelihood of developing nocturia37. Moreover, advancing age has been strongly associated with the occurrence of nocturia38. Specifically, nocturia is reported by only 0.4% of adults below the age of 40, whereas the prevalence increases to 11.5% among individuals aged 60 and above38. Additionally, untreated hypertensive patients were found to be 39% more likely to report nocturia compared to normotensive men39. Hence, the risk factors associated with nocturia encompass the process of aging, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity36,37,40,41, all of which contribute to the development of CKD42,43,44,45. In order to evaluate the influence of these factors on the relationship between nocturia and eGFR, an interaction test was conducted. The findings revealed that hypertension significantly impacted the association between nocturia and eGFR, potentially due to the occurrence of hypertensive diuresis46. In the present study, a sensitivity analysis was conducted, revealing that the association between nocturia and eGFR was consistent across both non-hypertensive and hypertensive populations.

In conclusion, our findings indicate a significant correlation between that nocturia and heightened frequency of nocturnal urination with decreased eGFR, a relationship that holds true for both CKD and non-CKD, hypertensive and non-hypertensive cohorts. Nevertheless, this association does not persist uniformly across various CKD prognostic risk populations, specifically the very high risk and high risk groups, for which our conclusions are not applicable. This finding indicates that the association between nocturia and heightened frequency of nocturnal urination, as well as eGFR, becomes insignificant once renal function reaches a certain level of impairment. This observation serves as a reminder for healthcare professionals that nocturia should be given more attention when it manifests in individuals with mild renal function abnormalities.

Our study possesses several notable strengths. Firstly, the utilization of a population-based strategy, multi-stage probability sampling, and a substantial sample size greatly enhance the generalizability of our findings. Secondly, we have conducted the first investigation into the correlation between nocturia and eGFR, thereby raising awareness among physicians regarding renal function in patients experiencing nocturia. Lastly, we have systematically stratified additional factors based on their influence on nocturia and evaluated their interactions with nocturia, thereby providing a potential mechanistic understanding of the impact of nocturia on renal function.

It is crucial to recognize the limitations of our study. Due to its cross-sectional nature, our investigation only allows for the identification of an association between nocturia exposure and eGFR, rather than establishing causal evidence. Furthermore, the diagnosis of nocturia relied on participants completing a voiding diary. However, the data regarding nocturnal urinary frequency were obtained from self-reported individuals who did not comply with a voiding diary, thereby necessitating the need to validate of our conclusions in individuals who experience increased nocturnal urination and diligently maintain a bladder diary. Furthermore, our findings were not evident in cases where the prognostic risk of CKD was deemed high or very high, which could potentially be attributed to the limited number of individuals falling within these specific risk categories. In order to achieve more precise findings, our objective is to conduct future research endeavors that encompass larger sample sizes within these two cohorts. Additionally, the data collection process was afflicted by uncertainty, leading to a significant amount of missing data in this study. To ensure the reliability of the results, the population with incomplete data was intentionally excluded from this analysis. Furthermore, the potential influence of prostate enlargement and overactive bladder syndrome on the outcomes of our study warrants consideration. In order to address this, participants who self-reported prostate enlargement were deliberately excluded from our study. However, the lack of available data pertaining to individuals with overactive bladder syndrome hindered our ability to definitively ascertain its impact on the results. Consequently, it is important to acknowledge that our study may not be entirely representative of the entire population of the US. Lastly, the limited availability of comprehensive drug-related data in the NHANES database posed a hindrance to our capacity to determine the impact of medications, including diuretics, on our findings. It is expected that forthcoming research endeavors will incorporate supplementary covariates to augment the credibility of our conclusion.

Conclusion

The presence of nocturia and heightened frequency of nocturnal urination exhibited a correlation with a decline in eGFR. Nevertheless, this association was not observed within the subsets of CKD patients classified as having a very high prognostic risk or high risk.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm. or it can be requested from the corresponding author and is available upon reasonable request.

References

Hashim, H. et al. International Continence Society (ICS) report on the terminology for nocturia and nocturnal lower urinary tract function. Neurourol. Urodyn. 38, 499–508. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.23917 (2019).

Presicce, F. et al. Variations of nighttime and daytime bladder capacity in patients with Nocturia: Implication for diagnosis and treatment. J. Urol. 201, 962–966. https://doi.org/10.1097/ju.0000000000000022 (2019).

Endeshaw, Y. W., Johnson, T. M., Kutner, M. H., Ouslander, J. G. & Bliwise, D. L. Sleep-disordered breathing and nocturia in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 52, 957–960. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52264.x (2004).

Weiss, J. P. & Everaert, K. Management of Nocturia and nocturnal Polyuria. Urology 133, 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2019.09.022 (2019).

Chen, F. Y. et al. Perception of nocturia and medical consulting behavior among community-dwelling women. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 18, 431–436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-006-0167-x (2007).

Dutoglu, E. et al. Nocturia and its clinical implications in older women. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 85, 103917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2019.103917 (2019).

Bozkurt, O. et al. Mechanisms and grading of Nocturia: Results from a multicentre prospective study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 75, e13722. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13722 (2021).

Kupelian, V. et al. Nocturia and quality of life: Results from the Boston area community health survey. Eur. Urol. 61, 78–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2011.05.065 (2012).

Funada, S. et al. Longitudinal analysis of bidirectional relationships between Nocturia and depressive symptoms: The Nagahama study. J. Urol. 203, 984–990. https://doi.org/10.1097/ju.0000000000000683 (2020).

Moon, S. et al. Association of nocturia and cardiovascular disease: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Neurourol. Urodyn. 40, 1569–1575. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.24711 (2021).

Feinfeld, D. A. & Danovitch, G. M. Factors affecting urine volume in chronic renal failure. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 10, 231–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-6386(87)80179-8 (1987).

Fujimura, T. et al. Nocturia in men is a chaotic condition dominated by nocturnal polyuria. Int. J. Urol. Off. J. Jpn. Urol. Assoc. 22, 496–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/iju.12710 (2015).

Chung, M. S. et al. Prevalence and associated risk factors of nocturia and subsequent mortality in 1301 patients with type 2 diabetes. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 46, 1269–1275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-014-0669-2 (2014).

Hsu, C. K., Wu, M. Y., Chiang, I. N., Yang, S. S. & Chang, S. J. Are middle-aged men with chronic kidney disease at higher risk of having nocturia than age-matched controls. Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms 7, 133–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/luts.12064 (2015).

Obayashi, K., Saeki, K. & Kurumatani, N. Association between melatonin secretion and nocturia in elderly individuals: A cross-sectional study of the HEIJO-KYO cohort. J. Urol. 191, 1816–1821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2013.12.043 (2014).

von Elm, E. et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 4, e296. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296 (2007).

Levey, A. S. et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 150, 604–612. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 (2009).

Carter, E. A. et al. Diabetes mellitus and impaired fasting glucose in Alaska Eskimos: The Genetics of Coronary Artery Disease in Alaska Natives (GOCADAN) study. Diabetologia 49, 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-005-0071-9 (2006).

Rattan, P. et al. Inverse Association of telomere length with liver disease and mortality in the US population. Hepatol. Commun. 6, 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep4.1803 (2022).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16, 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x (2001).

Manea, L., Gilbody, S. & McMillan, D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A meta-analysis. CMAJ 184, E191–E196. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.110829 (2012).

Waas, T. et al. Distribution of estimated glomerular filtration rate and determinants of its age dependent loss in a German population-based study. Sci. Rep. 11, 10165. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89442-7 (2021).

Vallon, V. & Komers, R. Pathophysiology of the diabetic kidney. Compr. Physiol. 1, 1175–1232. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c100049 (2011).

Jamshidi, P. et al. Investigating associated factors with glomerular filtration rate: Structural equation modeling. BMC Nephrol. 21, 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-020-1686-2 (2020).

Ridgway, A. et al. Nocturia and chronic kidney disease: Systematic review and nominal group technique consensus on primary care assessment and treatment. Eur. Urol. Focus 8, 18–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2021.12.010 (2022).

Kop, W. J. et al. Longitudinal association of depressive symptoms with rapid kidney function decline and adverse clinical renal disease outcomes. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. CJASN 6, 834–844. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.03840510 (2011).

Obayashi, K., Saeki, K., Negoro, H. & Kurumatani, N. Nocturia increases the incidence of depressive symptoms: A longitudinal study of the HEIJO-KYO cohort. BJU Int. 120, 280–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.13791 (2017).

Levey, A. S. et al. Nomenclature for kidney function and disease: Report of a kidney disease: Improving global outcomes (KDIGO) consensus conference. Kidney Int. 97, 1117–1129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.02.010 (2020).

Nielsen, S., Kwon, T. H., Frøkiaer, J. & Agre, P. Regulation and dysregulation of aquaporins in water balance disorders. J. Intern. Med. 261, 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01760.x (2007).

Verbalis, J. G. Renal physiology of nocturia. Neurourol. Urodyn. 33(Suppl 1), S6-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.22594 (2014).

Gulur, D. M., Mevcha, A. M. & Drake, M. J. Nocturia as a manifestation of systemic disease. BJU Int. 107, 702–713. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09763.x (2011).

Fukuda, M. et al. Polynocturia in chronic kidney disease is related to natriuresis rather than to water diuresis. Nephrol. Dialy. Transplant. Off. Publ. Eur. Dialy. Transpl. Assoc. Eur. Renal Assoc. 21, 2172–2177. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfl165 (2006).

Van der Weide, M. J. et al. Causes of frequency and nocturia after renal transplantation. BJU Int. 101, 1029–1034. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07292.x (2008).

Lose, G., Alling-Møller, L. & Jennum, P. Nocturia in women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 185, 514–521. https://doi.org/10.1067/mob.2001.116091 (2001).

Agarwal, R., Light, R. P., Bills, J. E. & Hummel, L. A. Nocturia, nocturnal activity, and nondipping. Hypertension 54, 646–651. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.109.135822 (2009).

Moon, S. et al. The association between obesity and the Nocturia in the U.S. population. Int. Neurourol. J. 23, 169–176. https://doi.org/10.5213/inj.1938062.031 (2019).

Fu, Z., Wang, F., Dang, X. & Zhou, T. The association between diabetes and nocturia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 10, 924488. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.924488 (2022).

Pesonen, J. S. et al. Incidence and remission of Nocturia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. 70, 372–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2016.02.014 (2016).

Victor, R. G. et al. Nocturia as an unrecognized symptom of uncontrolled hypertension in black men aged 35 to 49 years. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e010794. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.118.010794 (2019).

Huang, M. H., Chiu, A. F., Wang, C. C. & Kuo, H. C. Prevalence and risk factors for nocturia in middle-aged and elderly people from public health centers in Taiwan. Int. Braz. J. Urol. Off. J. Braz. Soc. Urol. 38, 818–824. https://doi.org/10.1590/1677-553820133806818 (2012).

Ihara, T. et al. Effects of fatty acid metabolites on nocturia. Sci. Rep. 12, 3050. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07096-5 (2022).

Ortiz, A., Mattace-Raso, F., Soler, M. J. & Fouque, D. Ageing meets kidney disease. Age Ageing https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afac157 (2022).

Tonelli, M. & Riella, M. C. World Kidney Day 2014: CKD and the aging population. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 63, 349–353. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.01.003 (2014).

Georgianos, P. I. & Agarwal, R. Hypertension in chronic kidney disease (CKD): Diagnosis, classification, and therapeutic targets. Am. J. Hypertens. 34, 318–326. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpaa209 (2021).

Mount, P. F. & Juncos, L. A. Obesity-related CKD: When kidneys get the munchies. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28, 3429–3432. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2017080850 (2017).

Ohishi, M., Kubozono, T., Higuchi, K. & Akasaki, Y. Hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and nocturia: A systematic review of the pathophysiological mechanisms. Hypertens. Res. Off. J. Jpn. Soc. Hypertens. 44, 733–739. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00634-0 (2021).

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 82160143) and Kidney Disease Engineering Research Center of Jiangxi Province (no. 20164BCD40095).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Research idea and study design and data acquisition: X.F.; data analysis/interpretation and statistical analysis: J.S; supervision or mentorship: B.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, J., Ke, B. & Fang, X. Association of nocturia of self-report with estimated glomerular filtration rate: a cross-sectional study from the NHANES 2005–2018. Sci Rep 13, 13924 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39448-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39448-0

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.