Abstract

Smoking is recognised as a critical public health priority due to its enormous health and economic consequences. Constant monitoring of the effectiveness of tobacco control programs calls for timely population-based data. This study reports the national and sub-national patterns in tobacco consumption among Iranian adults based on the results from the STEPwise approach to chronic disease risk factor surveillance (STEPS) survey 2021. This study was performed through an analysis of the results of the STEPS survey 2021 which had been conducted as a nationally representative cross-sectional study. Participants included Iranian adults aged ≥ 18 years in all provinces of Iran, who were selected via multistage cluster sampling method. Data were analyzed via survey analysis while considering population weights. The total number of participants was 27,874, including 15,395 (55.23%) women and 12,479 (44.77%) men. The all-ages prevalence of current tobacco smoking was 14.01% overall, 4.44% among women, and 25.88% among men. The all-ages prevalence of current cigarette smoking was 9.33% overall, 0.77% among women, and 19.95% among men. The all-ages prevalence of current hookah smoking was 4.5% overall, 3.64% among women, and 5.56% among men. The mean (SD) number of cigarettes smoked per day was 12.41 (10.27) overall, 7.65 (8.09) among women, and 12.64 (10.31) among men. The mean (SD) monthly times of hookah use was 0.42 (7.87) overall, 2.86 (23.46) among women, and 0.3 (6.2) among men. The national all-ages prevalence of second-hand smoking at home was 24.64% overall, 27.38% among women, and 20.26% among men. The national all-ages prevalence of second-hand smoking at work was 19.49% overall, 17.33% among women, and 22.94% among men. The tobacco consumption in Iran remains alarmingly high, indicating the current tobacco control policy implementation level is ineffective and insufficient. This calls for adopting, implementing, and enforcing comprehensive packages of evidence-based tobacco control policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Smoking, the second leading risk factor for deaths and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), has caused more than 200 million deaths over the last three decades1. It has been recognised as a critical public health priority due to its enormous health and economic consequences2. As a modifiable risk factor, the burden attributable to smoking could be minimised via the effective implementation of tobacco control interventions. Since the introduction of the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC)3, countries have made endeavors to implement demand-reduction tools, including reducing affordability through taxation, passing smoke-free laws, mandating health warnings on packaging, and banning tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship4.

Nevertheless, implementation and progress in tobacco control programs have varied substantially across countries5. As the success of tobacco control programs has slowed in many countries in the past decade, it is estimated that the total number of smokers continues to increase globally1. In this sense, constant monitoring of the effectiveness of previous tobacco control programs calls for timely population-based data on the prevalence of tobacco use for taking prompt public health measures6. The STEPwise approach to chronic disease risk factor surveillance (STEPS), developed by WHO, focuses on obtaining data on established risk factors that determine the burden of significant non-communicable diseases. The STEPS study has been conducted seven times in Iran in 2004, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2011, 2016 and 2021. This study reports the national and sub-national smoking prevalence and tobacco consumption among Iranian adults based on the results from the STEPS survey 2021.

Methods

Ethics approval

The study methodology conformed to Helsinki Declaration standards as revised in 1989. All experimental protocols were approved by the National Institute for Health Research under reference number IR.TUMS.NIHR.REC.1398.006. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation in the study. Moreover, the data used in the study did not include any identifiable personal information of participants, and the confidentiality of the data and the results are preserved.

Data source

Data were derived from the STEPS study 2021, a national cross-sectional survey carried out by the Non-Communicable Diseases Research Center (NCDRC). The STEPS survey required a nationally-representative sample. Five components were considered when estimating the sample size, including the confidence interval, margin of error, design effect, baseline index level, and non-response rate. The sample size for evaluating risk factors of NCDs in each province was calculated using a proportion to population size method. The survey used a systematic cluster classification method with 3176 clusters, each with ten participants, to conduct the study on the national level. Iranian adults aged above 18 residing in urban or rural areas of one of the 31 provinces were studied as the target population, excluding certain individuals such as those with mental disorders and pregnant women. In total, 28,821 participants from 3176 clusters were selected from rural and urban areas of the 31 provinces of Iran. A detailed description of the study population and the sampling method of the 2021 version of the STEPS survey has been published elsewhere7.

Variables

Smoking was assessed using the transcultural-adaption of the STEPS questionnaire, as proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in national STEPS surveys. Covariates included sociodemographic status of participants and their underlying conditions. Outcome variables included smoking-related variables. Sociodemographic variables included age, sex, province of residence, residential area, years of schooling, marital status, employment status, health insurance, complementary insurance, and wealth. Underlying conditions included body mass index (BMI), hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. Smoking-related variables included forms of smoking including cigarette smoking, hookah use, pipe smoking, and smokeless tobacco use; amount of cigarette smoking; frequency of smoking; tobacco consumption; history of ex-smoking; attempt to quit smoking; history of second-hand smoking; and place of second-hand smoking. Current tobacco smoking was defined as the use of smoked tobacco products, including cigarettes, pipes, or hookah, daily, non-daily or occasional basis in the past 12 months. Second-hand smoking, or passive smoking, was defined as being exposed to the smoke of any tobacco products in the past 30 days.

Statistical analysis

Data weighting

Data weighting was an important step between data cleaning and analysis in this survey. It was necessary to deal with incomplete data and non-response, as well as differences in the population characteristics. To ensure the reliability and validity of the results, a weighting procedure was used to adjust the survey data based on several factors. The four stages of the weighting procedure included: (a) weighting for general non-response, (b) weighting for non-response at each step of the survey, (c) weighting for age, sex, and area of residence, and (d) final weighting for the analysis of data. More information on the weighting process and equations used has been published elsewhere7.

Descriptive measures

Frequencies, proportions, means, and standard deviations were used to describe the data. We used the chi-square test for categorised variables. T-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test were used to analyse the differences among means of two groups and three groups or more, respectively. We considered p-values below 0.05 as significant.

Age standardisation

The National Population and Housing Census conducted by Iran's Statistical Center in 2016 was considered the standard population for direct age-standardisation to allow comparisons between provinces8.

Inequity analysis

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied to derive the household wealth index based on questions on key dwelling characteristics and household ownership, as described in the study protocol. PCA is an approach to statistical analysis in which multiple datasets are combined as orthogonal components9. The wealth index was used to divide the population into quintiles, whereby the first and fifth quintiles present the least fortunate and wealthiest households, respectively.

The concentration index with Erreygers' correction10 was used to quantify the degree of inequality in all types of smoking-related to wealth index and years of schooling. A zero concentration index would indicate no inequality related to wealth index or years of schooling. Negative values of concentration index would mean a higher prevalence of smoking among people with lower wealth index or years of schooling. Positive values of concentration index would indicate a higher prevalence of the type of smoking among people with higher wealth index or years of schooling11.

Model-based clustering method was applied to the data to achieve homogenous clusters regarding tobacco use on the sub-national level based on the smoking behaviours reported. We used data mining methods to determine the number of clusters and the combination of provinces in each cluster12,13.

Tools

All essential data analyses were performed using R statistical package v3.4.3 (http://www.r-project.org, RRID: SCR_001905). Data visualisations were performed using Python programming language, version 3.6 and R statistical package v3.4.3.

Results

Sociodemographic status

The total number of participants was 27,874, including 15,395 (55.23%) women and 12,479 (44.77%) men. The sociodemographic status of participants is presented in Table 1.

Prevalence of tobacco use

Prevalence of tobacco use among women and men of all ages

The all-ages prevalence (95% CI) of current tobacco smoking was 4.44% (4.09–4.82) among women, 25.88% (25.03–26.75) among men, and 14.01% (13.56–14.48) overall. The all-ages prevalence of current cigarette smoking was 0.77% (0.62–0.95) among women, 19.95% (19.17–20.75) among men, and 9.33% (8.95–9.72) overall. The all-ages prevalence of current hookah smoking was 3.64% (3.33, 3.98) among women, 5.56% (5.12–6.03) among men, and 4.5% (4.23–4.78) overall. The all-ages prevalence of all types of tobacco smoking among both sexes is presented in Table 2.

Age pattern of tobacco use prevalence

The prevalence (95% CI) of current cigarette smoking among men increased with age, from 8.01% (6.45–9.91) among men aged 18–24 to the observed peak of 26.43% (24.47–28.48) among age-group 45–54 years; however, it then decreased to 10.49% (8.08–13.51) among those aged more than 75. The prevalence of current use of hookah reached the observed peak of 11.03% (9.66, 12.56) among men and 5.87% (4.98, 6.9) women aged 25–34, then decreased to 2.03% (1.1–3.72) among men aged more than 75 and 2.53% (1.66–3.85) among women aged 65–69. Some 19.19% (16.83–21.78) and 6.97% (5.63–8.62) of men and women aged 18–24 years had used hookah at least once. The corresponding rates were 20.7% (18.91–22.61) and 8.88% (7.77–10.13) for men and women aged 25–34 years, respectively (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1).

Geographical pattern of tobacco prevalence

The age-standardised (95% CI) prevalence of all types of smoking varied significantly across the 31 provinces of Iran (Fig. 2a–c, Supplementary Table 2).

Geographical pattern of tobacco prevalence among women

The age-standardised prevalence (95% CI) of ever smoking among women ranged from 0.81% (0.19–3.35) in Ilam to 20.87% (17.62–24.54) in Sistan and Baluchistan. The prevalence of ever cigarette smoking among women ranged from Zero percent in Ilam, Hormozgan, Sistan and Baluchistan, and South Khorasan to 2.19% (1.19–4) in West Azerbaijan. The prevalence of ever use of hookah among women ranged from 0.23% (0.03–1.59) in Ardabil to 19.5% (16.38–23.06) in Sistan and Baluchistan. The prevalence of current smoking among women ranged from 0.39% (0.12–1.29) in Chahar Mahaal and Bakhtiari to 16.64% (13.69–20.08) in Sistan and Baluchistan. The prevalence of current cigarette smoking among women ranged from zero percent in Bushehr, Chahar Mahaal and Bakhtiari, Hormozgan, Ilam, North Khorasan Sistan, South Khorasan, Markazi, and Baluchistan to 1.59% (1.04–2.43) in Tehran. The prevalence of the current use of hookah among women ranged from zero percent in Ardabil and West Azerbaijan to 15.27% (12.47–18.56) in Sistan and Baluchistan (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Table 2).

Geographical pattern of tobacco prevalence among men

The age-standardised prevalence (95% CI) of ever smoking among men ranged from 20.94% (16.19–26.65) in South Khorasan to 45.99% (39.71–52.39) in Qazvin. The prevalence of ever cigarette smoking among men ranged from 13.28% (9.65–18.01) in South Khorasan to 39.02% (33.05–45.34) in Qazvin. The prevalence of ever use of hookah among men ranged from 3.68% (1.96–6.81) in Kermanshah to 22.38% (12.63–20.63) in Isfahan. The prevalence of current smoking among men ranged from 12.88% (9.31–17.57) in South Khorasan to 38.21% (32.25–44.55) in Qazvin. The prevalence of current cigarette smoking among men ranged from 7.29% (4.77–10.97) in South Khorasan to 32.39% (26.87–38.44) in Qazvin. The prevalence of current use of hookah among men ranged from 2.81% (1.38–5.66) in Kermanshah to 12.32% (9.31–16.12) in Isfahan (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Table 2).

Cigarette and hookah smoking

Cigarette and hookah smoking among women and men

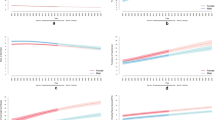

The all-ages mean (SD) cigarette pack/year was 17.56 (19.32) overall, 11.93 (17.35) among women, and 17.83 (19.37) among men. The mean (SD) number of cigarettes smoked per day was 12.41 (10.27) overall, 7.65 (8.09) among women, and 12.64 (10.31) among men. The mean (SD) monthly times of hookah use was 0.42 (7.87) overall, 2.86 (23.46) among women, and 0.3 (6.2) among men (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 3).

Age pattern of cigarette and hookah smoking

The mean (SD) number of cigarettes smoked per day increased with age, from 9 (9) among men and 4.28 (5.02) among women aged 18–24 to the observed peak of 13.87 (10.08) among men and 14.64 (7.73) among women aged 65–69 (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 3).

Geographical pattern of cigarette and hookah smoking

Cigarette and hookah smoking varied significantly among men and women across the 31 provinces of Iran (Fig. 4a–c, and Supplementary Table 4).

Geographical pattern of cigarette and hookah smoking among women

Among provinces with enough data, the mean cigarette pack/year ranged from 0.03 in Qazvin to 45 in Gilan. The median cigarette pack/year ranged from 0.03 in Qazvin to 45 in Gilan. The mean number of cigarettes smoked per day ranged from 0.03 in Qazvin to 18. 61 in Hamadan. The median number of cigarettes smoked per day ranged from 0.03 in Qazvin to 20 in Kermanshah, Gilan, Lorestan, and Fars. The mean monthly times of hookah use ranged from Zero in Alborz, Ardebil, East Azerbaijan, West Azerbaijan, Fars, Gilan, Golestan, Hamadan, Isfahan, Kerman, Kermanshah, Khuzestan, Lorestan, Mazandaran, Qazvin, Semnan, and Zanjan to 7.31 in Terhan. The median monthly times of hookah use ranged from Zero in Alborz, Ardebil, East Azerbaijan, West Azerbaijan, Fars, Gilan, Golestan, Hamadan, Isfahan, Kerman, Kermanshah, Razavi Khorasan, Khuzestan, Kurdistan, Kohgiluyeh and Boyer − Ahmad, Lorestan, Mazandaran, Qazvin, Semnan, Tehran and Zanjan to 4.29 in Qom and Yazd (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Table 4).

Geographical pattern of cigarette and hookah smoking among men

The mean cigarette pack/year ranged from 10.28 in Sistan and Baluchistan to 24.9 in West Azerbaijan. The median cigarette pack/year ranged from 4.5 in Kerman to 19.2 in Qom. The mean number of cigarettes smoked per day ranged from 7.93 in Razavi Khorasan to 17.4 in West Azerbaijan. The median number of cigarettes smoked per day ranged from 6 in Razavi Khorasan to 20 in West Azerbaijan and East Azerbaijan. The mean monthly times of hookah use ranged from zero in Ardebil, Chahar Mahaal and Bakhtiari, Hormozgan, Ilam, North Khorasan, South Khorasan, and Qazvin to 5.24 in Sistan and Baluchistan. The median monthly times of hookah use was zero in all provinces (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Table 4).

Prevalence of second-hand smoking

Prevalence of second-hand smoking at home

The national all-ages prevalence (95% CI) of second-hand smoking at home was 24.64 (24.05–25.24) overall, 27.38 (26.59–28.18) among women, and 20.26 (19.39–21.17) among men. The prevalence of second-hand smoking at home decreased with age among both sexes, from 29.35% (27.39–31.39) among age-group 18–24 to 16.17% (13.74–18.93) among those aged 70–74. It then rose to 18.72% (16.22–21.52) among those aged more than 75. The prevalence of second-hand smoking at home among women ranged from 14.94% (11.11–19.79) % in Alborz to 48.9% (43.5–54.33) in Kerman. The prevalence of second-hand smoking at home among men ranged from 8.2% (5–13.17) in Alborz to 39.14% (32.84–45.83) in Kerman (Figs. 2, 5, Supplementary Tables 1, 2).

Prevalence of second-hand smoking at work

The national all-ages prevalence (95% CI) of second-hand smoking at work was 19.49% (18.95–20.05) overall, 17.33% (16.67–18.02) among women, and 22.94% (22.01–23.9) among men. The prevalence of second-hand smoking at work among both sexes increased from 22.92% (21.11–24.84) among age-group 18–24 to 23.98% (22.62–25.39) among age-group 25–34. The prevalence of second-hand smoking at work among women ranged from 6.91% (4.47–10.53) in Semnan to 36.7% (31.91–41.77) in Kurdistan. The prevalence of second-hand smoking at work among men ranged from 14.37% (10.06–20.1) in South Khorasan to 43.44% (35.72–51.49) in Ardabil (Figs. 1, 5, Supplementary Tables 1, 2).

Determinants of tobacco smoking

Wealth and years of schooling

On the national level, lower wealth index or years of schooling were associated with higher prevalence of ever or current tobacco smoking among both women and men (Table 3). Nevertheless, wealth index and years of schooling had varying roles in tobacco smoking prevalence among women and men across provinces in Iran (Fig. 6, Supplementary Table 5).

Geographical pattern

Using model-based clustering, the 31 provinces of Iran were categorized into four clusters based on prevalence of ever tobacco smoking, ever cigarette smoking, current tobacco smoking, and current cigarette smoking (Fig. 7). The prevalence of smoking among the four clusters is presented in Table 4.

Model based clustering of Iran 31 provinces into four clusters based on prevalence of ever tobacco smoking, ever cigarette smoking, current tobacco smoking, and current cigarette smoking. AL Alborz, AR Ardebil, EA Azerbaijan-East, WA Azerbaijan-West, BS Bushehr, CM Chahar-Mahal-Bakhtiari, FA Fars, GI Gilan, GO Golestan, HD Hamedan, HG Hormozgan, IL Ilam, ES Isfahan, KE Kerman, BK Kermanshah, KN North Khorasan, KR Razavi Khorasan, KS South Khorasan, KZ Khuzestan, KB Kohkiluyeh-and-Boyer-Ahmad, KD Kurdistan, LO Lorestan, MK Markazi, MN Mazandaran, QZ Qazvin, QM Qom, SM Semnan, SB Sistan-and-Baluchestan, TE Tehran, YA Yazd, ZA Zanjan.

Discussion

The study showed that 14% of the Iranian adults, 4.4% of women and 25.9% of men, were current tobacco smokers in 2021. Some 9.3% of the study participants, 0.8% of women and 20% of men, were current cigarette smokers. Moreover, the all-ages prevalence of current hookah use was 3.6% among women and 5.6% among men. Pipe smoking and smokeless tobacco were unpopular among the Iranian population.

The prevalence of current tobacco smoking since the previous STEPS survey in 2016 has stagnated: form 14.1% in 2016 to 14% in 2021. Nevertheless, the mean number of cigarettes smoked per day has increased from 10.4 in 2016 to 12.4 in 202114.

There was a heterogeneous geographical distribution pattern in tobacco smoking prevalence in Iran, distinctively witnessed among the smoking behaviour of women and men, depending on the type of smoking. In northwestern Iran, West Azerbaijan had the second-highest prevalence of current cigarette smoking among men and the fourth-highest among women. Nevertheless, it ranked 16th in terms of current hookah use among men, and the prevalence was nearly zero among women. In southwestern Iran, Bushehr had the highest prevalence of current hookah use among both women and men, while having nearly zero prevalence of current cigarette smoking among women and being ranked as the third-lowest in terms of prevalence among men. In southeastern Iran, women in Sistan and Baluchistan had the second-highest prevalence of current hookah use while having nearly zero prevalence of current cigarette smoking. Sistan and Baluchistan also had the highest prevalence of smokeless tobacco use. The geographical pattern also conformed to neighbouring countries1,15, possibly due to ethnic, cultural, and access resemblance16.

Using data mining techniques, we grouped Iran’s provinces into four clusters with similar prevalence of ever tobacco smoking, ever cigarette smoking, current tobacco smoking, and current cigarette smoking. In provinces in cluster 1, smoking cessation policies need to be prioritized, while other forms of tobacco use, namely hookah are less pressing issues. In cluster 2, which interestingly maps to northwestern Iran, both cigarette smoking and tobacco use need to be addressed. In provinces in cluster 3 both ever/current prevalence of tobacco and cigarette smoking are low. Cluster 4 is consistent with central, southern, and eastern provinces, where tobacco consumption needs to be addressed. The clustering of provinces could empower Iranian authorities in decision-making and public policy efforts regarding tobacco control. This needs to be further investigated in future studies which particularly focus on proposing tobacco reduction policies based on the real-world data. Notably, upon interpretation of the results of model-based clustering, the role of smoking determinants reported in this study including wealth index and years of schooling need to be considered for policy and intervention development.

The prevalence gap between men and women was narrower in the current hookah use compared with current cigarette smoking. The prevalence of hookah use is more than cigarette smoking among women. Moreover, women tend to have more positive attitudes towards hookah use, which is much less stigmatised than cigarette smoking17. In recent years, the prevalence of hookah use among women has increased more than men18. Alarmingly, the study showed that women's mean monthly times of hookah use was more than nine times that of men. Meanwhile, there is evidence that the deleterious effects of hookah use on women could be higher than in men19.

There was an interest in hookah use, particularly among younger adults. Some 19% and 7% of men and women aged 18–24 years had used hookah at least once. Moreover, the prevalence of current hookah use reached a surprisingly early peak of 11% among men and 6% women aged 25–34. Despite supposedly more deleterious effects of hookah use than cigarette smoking20, there has been a growing interest in hookah use in recent decades21. While hookah use is considered recreational in Iran16, there is evidence that hookah users are increasingly susceptible to cigarette smoking22,23.

Six decades after the first documentations of the deleterious health effects of tobacco use24, there has been substantial progress in reducing the prevalence of tobacco smoking worldwide. In contrast, it is estimated that the age-standardised prevalence of current tobacco smoking has increased by 8% among men and 2% among women in the past three decades in Iran and the population growth has also led to a marked increase in the number of smokers1. Since introducing the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) in 2005, outlining demand-reduction policies, many counties have witnessed drastic decreases in the prevalence of tobacco smoking25. Taking a closer look at the previous STEPS surveys in Iran, the smoking prevalence of Iranian adults has somewhat stagnated since 2004 among both men and women26. Simultaneously, Brazil, Norway, and Senegal have managed to decrease the prevalence of tobacco smoking by 73%, 54%, and 51%, respectively. Iceland, Denmark, Canada, Australia, Colombia, and Costa Rica, also witnessed nearly 50% decreases in the prevalence of tobacco smoking1.

Though once an early adapter to FCTC16, the current tobacco control policy implementation level is insufficient in Iran. In the absence of any new concerted effort towards smoking reduction, sanctions and subsequently the economic downturn could have played a significant role in the slight reduction of smoking prevalence in Iran since 201614,16,27. Evidence shows that economic recessions are associated with decreased cigarette consumption via decreasing its affordability16. Overall, cigarettes have become less affordable in Iran, particularly since 201828. The purchase pattern of Iranian smokers has changed from the whole box of cigarettes to the single stick cigarette. In addition, smokers have generally swapped to less expensive cigarettes29. Dealing with the burden attributable to tobacco use, public health authorities encounter substantial obstacles such as an increased number of smokers due to population growth, pressure from the tobacco industry, and competing for health and political priorities1. WHO discourages Iran from implementing high import duties as they encourage domestic production of tobacco. Direct taxation also needs to be excised rather than other indirect taxes.

Moreover, uniform tax rates are recommended to avoid product switching28. There is evidence that tobacco taxation, as one of the most cost-effective tobacco control policies30, needs to be concordantly adjusted to people's purchasing power to remain potent and reduce affordability31. Moreover, the revenue from tobacco taxation needs to be redistributed to tobacco control programs, health care services, and social support services30. Unless strict regulations are in place to control cigarette smuggling, any increase in cigarette price could be compensated by flooding smuggled cigarettes into the market29. This calls for substantially reducing smoking rates in the country via adopting, implementing, and enforcing comprehensive packages of evidence-based tobacco control policies. The witnessed heterogeneities and determinants in the patterns of smoking prevalence and tobacco consumption need to be taken into account when prioritizing vulnerable groups and designing tobacco reduction strategies, especially considering the relative authority of the medical universities of Iran in sub-national healthcare programs implementation32. Otherwise, the death toll, imposed economic costs, and the burden to health systems caused by smoking will increase over the years.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study lies in its large sample size. Given the sampling method, the results could represent the Iranian population. The study investigated the smoking prevalence and tobacco consumption pattern by age, sex, province of residence, wealth, and years of schooling. This could empower public health authorities to make evidence-based decisions and design tobacco reduction action plans based on various determinants according to real-world data, especially considering that individual level data were used for assessing the inequality patterns. Moreover, this was the first nationwide study from Iran to investigate pipe smoking and the use of smokeless tobacco. Given the use of electronic and online data gathering tools, the study had very little missing data. To minimise the missing data, the software used for data collection was designed to avoid ignoring obligatory questions. Moreover, the estimated sample size was initially calculated to be 10% higher than the required sample size so that potential missing data did not violate the sample representativeness.

Conclusion

The tobacco consumption in Iran remains alarmingly high, indicating the current tobacco control policy implementation level is insufficient. This calls for adopting, implementing, and enforcing comprehensive packages of evidence-based tobacco control policies. In the meantime, the witnessed heterogeneities in the patterns of smoking prevalence and tobacco consumption need to be considered when designing tobacco reduction strategies. Otherwise, the death toll, imposed economic costs, and the burden to health systems caused by smoking will increase over the years.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Reitsma, M. B. et al. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 397, 2337–2360 (2021).

Jha, P. & Peto, R. Global effects of smoking, of quitting, and of taxing tobacco. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 60–68 (2014).

W. H. Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. (2003).

Chung-Hall, J., Craig, L., Gravely, S., Sansone, N. & Fong, G. T. Impact of the WHO FCTC over the first decade: A global evidence review prepared for the Impact Assessment Expert Group. Tob. Control 28, S119–S128 (2019).

World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2019 : Offer Help to Quit Tobacco Use (2019).

Bilano, V. et al. Global trends and projections for tobacco use, 1990–2025: An analysis of smoking indicators from the WHO comprehensive information systems for tobacco control. Lancet 385, 966–976 (2015).

Protocol Design for Surveillance of Risk Factors of Non-Communicable Diseases During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Experience from Iran STEPS Survey 2021. http://journalaim.com/Article/aim-23947 (2021).

Statistical Center of Iran. Population and Housing Censuses. https://www.amar.org.ir/english/Population-and-Housing-Censuses.

Rencher, A. C. & Schimek, M. G. Methods of multivariate analysis. Comput. Stat. 12, 422 (1997).

Erreygers, G. Correcting the concentration index. J. Health Econ. 28, 504–515 (2009).

O’Donnell, O., O’Neill, S., Van Ourti, T. & Walsh, B. conindex: Estimation of concentration indices. Stand. Genomic Sci. 16, 112 (2016).

Parsaeian, M. et al. Introducing an efficient sampling method for national surveys with limited sample sizes: Application to a national study to determine quality and cost of healthcare. BMC Public Health 21, 1–10 (2021).

Abbasi-Kangevari, M. et al. Quality and cost of healthcare services in patients with diabetes in Iran: Results of a nationwide short-term longitudinal survey. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1099464 (2023).

Varmaghani, M. et al. Prevalence of smoking among Iranian adults: Findings of the national steps survey 2016. Arch. Iran. Med. 23, 369–377 (2020).

Kendrick, P. J. et al. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of chewing tobacco use in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 6, e482–e499 (2021).

Sohrabi, M.-R., Abbasi-Kangevari, M. & Kolahi, A.-A. Current tobacco smoking prevalence among Iranian population: A closer look at the STEPS surveys. Front. Public Health 8, 571062 (2020).

Burki, T. K. Tobacco control in Jordan. Lancet Respir. Med. 7, 386 (2019).

Dadipoor, S. et al. Explaining the determinants of hookah consumption among women in southern Iran: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 19, 1–13 (2019).

Salameh, P., Khayat, G. & Waked, M. Lower prevalence of cigarette and waterpipe smoking, but a higher risk of waterpipe dependence in Lebanese adult women than in men. Women Health 52, 135–150 (2012).

Jukema, J. B., Bagnasco, D. E. & Jukema, R. A. Waterpipe smoking: not necessarily less hazardous than cigarette smoking: Possible consequences for (cardiovascular) disease. Neth. Hear. J. 22, 91 (2014).

Qasim, H. et al. The effects of hookah/waterpipe smoking on general health and the cardiovascular system. Environ. Health Prevent. Med. 24, 1–17 (2019).

Bahelah, R. Curiosity and susceptibility to cigarette smoking among cigarette-naïve, waterpipe smoking US youth: National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2014. Tobacco Prevent. Cessation 3, 132 (2017).

Soneji, S., Sargent, J. D., Tanski, S. E. & Primack, B. A. Associations between initial water pipe tobacco smoking and snus use and subsequent cigarette smoking: Results from a longitudinal study of US adolescents and young adults. JAMA Pediatr. 169, 129–136 (2015).

Doyle, J. T., Dawber, T. R., Kannel, W. B., Heslin, A. S. & Kahn, H. A. Cigarette smoking and coronary. Heart Dis. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM196204192661602266,796-801 (2009).

Gravely, S. et al. Implementation of key demand-reduction measures of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and change in smoking prevalence in 126 countries: An association study. Lancet Public Health 2, e166–e174 (2017).

Sohrabi, M.-R., Abbasi-Kangevari, M. & Kolahi, A.-A. Current tobacco smoking prevalence among Iranian population: A closer look at the STEPS surveys. Front. Public Health 8, 945 (2020).

Abbasi-Kangavari, M. et al. Current inequities in smoking prevalence on district level in Iran: A systematic analysis on the STEPS survey. J. Res. Health Sci. 22, e00540 (2021).

Mediterranean, W. H. Organization. R. O. for the E. Tobacco Tax: Islamic Republic of Iran.

Golestan, Y. P. et al. The effect of price on cigarette consumption, distribution, and sale in Tehran: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 21, 1–9 (2021).

WHO. Earmarked Tobacco Taxes: Lessons Learnt from Nine Countries. Preprint (2016).

Institute, U. N. C. & WHO. Monograph 21. The Economics of Tobacco and Tobacco Control. Preprint (2016).

Peykari, N. et al. National action plan for non-communicable diseases prevention and control in Iran; A response to emerging epidemic. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 16, 3 (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: F.F., Ne.R., M.A.-K.; Data curation: F.F., Ne.R., Na.R., Y.F., E.G., M.Y., E.F.M., M.N., M-M.R., N.F., N.A., M.Ma., A.G.; Formal Analysis: A.G., M.Ma., N.A., M-R.M., E.G., M.N., M.A.-K.; Funding acquisition: F.F.; Investigation: F.F., Ne.R.; Methodology: F.F., Ne.R., M.-R.M., N.A., M.Ma., A.G.; Project administration: F.F., Ne.R.; Resources: F.F., Ne.R., Na.R.; Supervision: F.F., Ne.R.; Validation: F.F., Ne.R., A.G., M.Ma., N.A., M-R.M., M.A.-K.; Visualisation: M.A.-K., M.-R.M., M.Ma.; Writing-original draft: M.A.-K.; Writing-review & editing: M.A.-K., A.G., M.-R.M., M.Ma., N.A., S.-H.G., M.N., N.F., M.-M.R., A.M., Z.A.-K., Na.R., E.F.M., M.Mo., Ne.R., F.F.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abbasi-Kangevari, M., Ghanbari, A., Fattahi, N. et al. Tobacco consumption patterns among Iranian adults: a national and sub-national update from the STEPS survey 2021. Sci Rep 13, 10272 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-37299-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-37299-3

This article is cited by

-

Prevalence of tobacco use among cancer patients in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis

BMC Public Health (2024)

-

Effects of educational interventions based on the theory of planned behavior on oral cancer-related knowledge and tobacco smoking in adults: a cluster randomized controlled trial

BMC Cancer (2024)

-

Prevalence of plasma lipid abnormalities and associated risk factors among Iranian adults based on the findings from STEPs survey 2021

Scientific Reports (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.