Abstract

Many studies have reported positive contributions of health promotion on the health behavior of nursing staff working in hospitals, including the maintenance of a regular healthy diet, engagement in physical activity, performance of routine screening practices, and participation in a health examination. Despite being considered a role model for healthy lifestyles, little is known about the effect of health-promoting hospital settings on nursing staff. The aim of this study was to perform a nationwide, hospital-based, cross-sectional, survey comparing health practices between full-time nurses of health-promoting hospitals and those of non-health-promoting hospitals in Taiwan. We conducted a nationwide, hospital-based, cross-sectional, survey in 100 hospitals from May to July 2011 using a questionnaire as the measurement tool. Nurses aged between 18 and 65 years from certified health-promoting hospitals (n = 14,769) were compared with nurses in non-health-promoting hospitals (n = 11,242). A multiple logistic regression model was conducted to estimate the effect of certified HPH status on the likelihood of performing health behavior, receiving general physical examination, undergoing cancer screening, and participating in hospital-based health-promoting activities. All nurses of HPH hospitals were more likely to perform physical activity, practice cancer screening, receive at least one general physical examination in the past 3 years, and had a higher chance of participating in at least one hospital-based health-promoting activity in the past year (particularly weight-control groups and sports-related clubs) than those of non-HPH hospitals. This study suggests the effectiveness of implementing health promotion on the health behavior of full-time nursing staff in hospitals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Health promotion and disease prevention are integral parts of primary healthcare management. Ever since the mid-1980s, the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion has received considerable attention globally1. In 1988, the World Health Organization (WHO) initiated the Network of the health-promoting hospital (HPH). The HPH initiative aims at reorienting hospital services and resources toward health promotion and disease prevention2. The implementation of HPH has been recognized as a core strategy to encourage healthier lifestyles and behaviors in disease prevention among healthcare workers and patients. Many studies have reported the positive contribution of health promotion on the health behavior of nursing staff working in hospitals, including the maintenance of a regular healthy diet, engagement in physical activity, performance of routine screening practices, and participation in health examinations3,4,5,6,7. Since its establishment, the HPH initiative has now been adopted by more than 700 hospitals and health service members in more than 40 countries worldwide. The Taiwan HPH Network became the first Asian member of the WHO's international HPH network in 2006. With strong commitment from the Taiwanese health authorities, it has become the largest domestic HPH network globally with 162 members by 2016 (147 hospitals, 13 township public health centers, and 2 long-term care facilities)2.

Despite the fact that physicians have ultimate responsibility for the care of their patients, hospital authorities continue to increase the work responsibility of nurses to implement patient care8. Being the largest primary health care professional group working at hospitals, the health practice of nurses is important because they spend more time with their patients, and provide more direct care with them than the doctors. Nurses who practice healthy behaviors may influence their patients to adopt healthy lifestyles9,10,11,12,13. In fact, the general public has more confidence in nurses who are normal-weight to provide general advice about diet and such as reducing calorie intake and increasing exercise to overweight or obese patients to achieve weight loss than those who are overweight13,14. Nurses who are ex-smokers or non-smokers have more positive attitudes and are more motivated to engage in smoking cessation for their patients than nurses who smoked11,12. When compared to nurses who are physically inactive, nurses who regularly exercise are more likely to encourage physical activity among patients9,10.

The HPH initiative also had a positive impact on implementing health promotion strategies among hospitals in Taiwan3,15,16,17,18,19. Although HPH had a positive effect on hospital workers, the nursing staff had significantly fewer days “exceeding 30-min of walking or equivalent physical activity” and “having 5 portions of fruits and vegetables” during the past week as well as were less likely to participate in health-promoting activities provided by hospitals (participation in sports-related clubs, weight-control groups, and recreational or service clubs; use of gym or sports equipment; attending lectures) than physicians, pharmacists, and other health professionals3. Notwithstanding their increased awareness and greater accessibility to healthcare services, nurses exhibit lower rates of Pap smear screening in comparison to the general population6. Variances in individual characteristics, encompassing age, gender, and comorbidity, may significantly influence an individual's health-promoting practices. A previous study has identified that male healthcare professionals or healthcare professionals aged over 45 years have a higher likelihood of engaging in physical activity19. Nevertheless, little is known about the effect of health-promoting hospital settings on the overall health practices (health behavior, health screening, and participation in hospital-based health-promoting activities provided by hospitals) of nursing staff alone, which is particularly important when considering them as a role model for healthy lifestyles. Moreover, little is known about the interrelationship among health-promoting hospital settings, individual differences (age, gender, and comorbidity), and health-promoting practices in nurses.

Health-promoting hospital settings and individual differences (age, gender, and comorbidity) are independent and significant predictors of health practices among healthcare professionals. In addition, age, gender, and comorbidity of individuals were considered to affect the choices of lifestyle, which may change the effect of health-promoting hospital settings on health practices. This study examined the relationship between health-promoting hospital settings and health practices among nurses using a nationwide, hospital-based survey in Taiwan. We further examined whether this relationship was moderated by age, gender, and baseline chronic disease.

Subjects and methods

Study design and participants

In Taiwan, all Taiwan’s civilian residents were covered under a single-payer government-operated insurance program. A global budget was negotiated on an annual basis between the Department of Health and healthcare providers of all accredited hospital levels (district hospital, regional hospital, or medical center). Private providers dominate Taiwan’s healthcare market.

We conducted a nationwide, hospital-based, cross-sectional, survey in 100 hospitals from May to July 2011 using the questionnaire as a measurement tool. The questionnaire was developed and collected by the Taiwan Bureau of Health Promotion (BHP) to assess the personal health practices, health-related behaviors, and psychosocial work environment of full-time hospital staff members. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. To protect survey respondents’ confidentiality, data were collected using a self-administered, anonymous, and structured questionnaire, which was developed for comprehension and ease of completion among hospital workers. Cover letters, paper-based questionnaires, and reply envelopes were sent to 98,817 full-time staff members at the participating hospitals. After completing the questionnaire, participants were asked to place the anonymous questionnaire in a sealed envelope and return it to a collection site at the hospital. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Taiwan BHP (Investigation No. 0990800708). The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The details of the study design are described in our previous investigation20.

We referred certified HPH hospitals to member hospitals of the Taiwan HPH Network. In 2011, there were 66 certified HPH (6 medical centers, 45 regional hospitals, and 15 district hospitals) and 421 non-HPH certified hospitals (17 medical centers, 40 regional hospitals, and 364 district hospitals) in Taiwan. To ensure a fair representation, we randomly selected non-Health Promoting Hospitals using a 1:1 ratio based on the distribution of accredited hospital levels. According to the accredited hospital level, we invited all 66 certified HPH and 61 randomly matched non-HPH certified hospitals to participate in the study. A total of 100 hospitals [55 (83.3%) certified HPH and 45 non-HPH certified (81.8%) hospitals] agreed to participate in this survey.

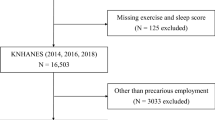

We received 70,622 completed questionnaires, for a response rate of 71.5% (73.6% from HPH and 68.7% from non-HPH certified hospitals). A total of 33,592 respondents reported themselves as full-time licensed registered or practical nurses. To maintain homogeneity in work patterns as suggested by a previous study19, we only included nurses who worked in the five main hospital units, including the operating or delivery room; outpatient clinic; emergency room or intensive care unit; general ward; or administration department. Since the mandatory retirement age for insured workers was 65 in Taiwan, we excluded respondents aged less than 18 and older than 65 years. After excluding those with incomplete information or missing information on independent variables of interest, a total of 26,011 nurses aged between 18 and 65 years were included in the study cohort. Nurses from the certified HPH hospitals were included in the HPH group (n = 14,769, 56.8%), and the remaining nurses in the non-HPH group (n = 11,242, 43.2%; see Supplementary Fig. S1).

Measurements

Independent covariates included baseline participant characteristics (age, sex, education level, marital status), health status (obese status, presence or absence of chronic disease), healthy lifestyle (smoking and drinking status), work unit, and hospital characteristics (accredited level and ownership). Age was assessed in years and subsequently divided into two categories: 18–39 years and 40–65 years. Educational level options encompassed junior high school or below, senior high school, vocational school, university, and post-graduate education. Marital status was determined as unmarried, married, separated, divorced, or widowed. The body-mass index cut-off point for obesity (≥ 27 kg/m2) was defined by the Health Promotion Administration in Taiwan. Chronic diseases included but were not limited to diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, viral hepatitis, insomnia, asthma, and fatty liver. Smoking status was stratified into three categories: never, former, and current; while drinking habits were categorized into never, occasional, small regular amounts, and large regular amounts. Accredited hospital level (medical center, regional hospital, or district hospital) was stipulated by the Taiwan Joint Commission on Hospital Accreditation.

The primary outcomes of the study included (1) health behavior (physical activity and dietary behavior); (2) health screening (general physical examination and cancer screening practice), and (3) participation in hospital-based health-promoting activities (attending lectures, participation in sports-related clubs, use of gym or sports equipment, participation in weight-control groups, and participation in recreational or service clubs).

Health behaviors (physical activity and dietary behavior) were determined by enquiring the number of days "walking exceeding 30 or more minutes or equivalent physical activity" and "eating at least five portions of fruits and vegetables" during the past week. The frequency of physical activity and dietary behaviors was divided into 0, 1–2, 3–4, 5–6, and 7 days per week.

Health screening (general physical examination and cancer screening practices) was enquired as "how long it had since their last examination (including general physical examination, Papanicolaou (Pap) smear, mammography examination, and fecal occult blood test)". General physical examination was measured using a 5-point Likert-scale item from 1 (none), 2 (more than 6 years), 3 (4–6 years), 4 (1–3 years), and 5 (less than one year). A Pap smear (also known as Pap test) is a screening method used to detect cervical cancer in women. The time elapsed since the last pap smear test was divided into > 6 years, 4–6 years, 1–3 years, < 1 year, never and females older than 30 years, never and females younger than 30 years, and male (not applicable). Mammography examination was measured using a 6-point Likert-scale item from 1 (less than 2 years), 2 (2–4 years), 3 (more than 4 years), 4 (never and female older than 40 years), 5 (never and female younger than 40 years), to 6 (male). Fecal occult blood test was measured using a 4-point Likert scale item from 1 (never), 2 (more than 4 years), 3 (2–4 years), to 4 (less than 4 years).

Participation in hospital-based health-promoting activities on a healthy diet and sport-related fitness was determined by enquiring "during the past year, did you participate in the indicated activities (including lectures, clubs/groups, and use of gym or sports equipment)?" Participation in health-related lectures was measured using a 3-point Likert scale item from 1 (none), 2 (a couple of times) to 3 (often), whereas participation in clubs/groups and use of gym or sports equipment were measured using a 5-point Likert scale item from 1 (none), 2 (less than once time a month), 3 (at least once a month), 4 (once or twice a week) to 5 (more than 3 times a week).

We constructed our primary outcomes as binary variables into none or at least one incidence (including at least one day walking exceeding 30 min or five portions of fruits and vegetables during the past week; at least one general physical examination in the past 3 years, Pap smear in the past 3 years (all age or older than 30 years), mammography examination in the past 2 years (all age or older than 45 years), fecal occult blood test in the past 2 years; and participated in at least one hospital-based health-promoting activities in the past year).

Statistical analysis

The dissimilarities in baseline participant and hospital characteristics, health status, and work unit between the HPH and non-HPH hospitals were compared using the Student’s t-test for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi-square test (χ2) for categorical variables. The multivariate logistic regression model was conducted to estimate the effect of certified HPH status on the likelihood of performing health behavior, receiving general physical examination, undergoing cancer screening, and participating in hospital-based health-promoting activities, with adjustment for participant and hospital characteristics, health status, health behavior, and work unit. To account for the potential interaction effects between certified HPH status and individual differences on health practices, sex (male or female), age (younger or older than 40 years), and chronic disease were also used as stratification variables in the logistic model. All data transformation and statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All statistical assessments were considered significant at P < 0.05 based on two-sided tests.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 compares the baseline participant characteristics, health behavior, work unit, and hospital characteristics between nurses in the HPH and non-HPH hospitals. Slightly more than half of the nurses worked in the HPH hospitals (56.8%). Most nurses were women (98.2%), aged between 18 and 39 years (84.8%), holders of a university or postgraduate degree (57.7%), unmarried (56.2%), and workers in private (67.5%) or regional hospitals (65.3%). Only 10.1% of nurses were obese and about 27.3% reported having chronic diseases, particularly insomnia (14.4%), fatty liver (4.7%), and lipidemia (4.6%). Less than 1.3% of nurses were current smokers and 2.6% were regular drinkers. Overall, most nurses worked in the general ward 11,452 (44.0%), followed by 6608 (25.4%) in the emergency room or ICU, 4062 (15.6%) in the outpatient clinic, 3226 (12.4%) in operating or delivery room, and 663 (2.5%) in administration.

Unadjusted and adjusted analyses by certified HPH status of the hospital

Table 2 compares the adjusted and unadjusted odds ratio of health-related behaviors and screening practices associated with the HPH status of the hospital. The dietary intake of five portions of fruit and vegetables in at least one day during the past week was high for all nurses (85.5%-86.3%). Nurses of HPH hospitals were more likely to perform physical activity (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.12; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.07–1.19) or receive at least one general physical examination in the past 3 years (aOR 1.27; 95% CI, 1.18–1.36) than those of non-HPH hospitals. When considering cancer screening practice alone, a significantly higher proportion of nurses in HPH hospitals practiced cancer screening than those in the non-HPH hospitals (55.1% vs 47.0%, P < 0.001). After adjusting for participant and hospital characteristics, health status, health behavior, and work unit, only physical activity, the HPH effect increased the cancer screening practices by 62% (aOR 1.62; 95% CI 1.53–1.71), particularly the increased in fecal occult blood test screening in the past 2 years by 153% (aOR 2.53; 95% CI 2.37–2.70). Overall, the participation level in at least one hospital-based health-promoting activity in the past year was high for all nurses (43.0–46.0%). All nurses of HPH hospitals had a higher chance of participating in most activities, particularly sports-related clubs (24.7% vs 20.7%, P < 0.001) and weight-control groups (13.4% vs 8.9%, P < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences in attending health-promoting lectures between nurses of HPH and non-HPH hospitals even in stratified analyses by sex, age, and chronic disease.

The associations of HPH status, sex, age, and chronic disease with health practices are presented in Tables 3, 4, and 5. The interactions between HPH status and sex, between HPH status and age as well as between HPH status and chronic disease were significantly associated with health practices. Male nurses in HPH (aOR 2.53, 95% CI: 1.81–3.54), male nurses in non-HPH (aOR 2.12, 95% CI: 1.52–2.94), and female nurses in HPH (aOR 1.12, 1.07–1.18) were more likely to engage in exceeding 30 min of walking or equivalent physical activities when compared to female nurses in non-HPH settings. Male nurses in HPH, male nurses in non-HPH, and female nurses in HPH were also more likely to participate in sports-related clubs and use gym or sport equipment provided by hospitals when compared to female nurses in non-HPH settings.

We further stratified our study cohort by sex (Table 6). After covariate adjustment, the HPH effect was associated with an increased likelihood to perform physical activity and receive at least one general physical examination in the past 3 years in female nurses. Female nurses of HPH hospitals had significantly higher screening practices of pap smear in the past 3 years (39.8% vs 37.7%; older than 30 years, 57.2% vs 53.3%) and mammography examination in the past 2 years (10.2% vs 7.7%; older than 45 years, 47.5% vs 33.7%) than those of non-HPH hospitals. On the other hand, male nurses of HPH hospitals had a much higher chance of undergoing fecal occult blood test in the past 2 years (aOR 2.80 vs 2.53) and participating in hospital-based health-promoting activities in the past year (aOR 2.13 vs 1.14) than female nurses. Table 7 stratified nurses into two age groups (18–39 y, 40–65 y). In both age strata, nurses in HPH hospitals had a similar tendency as in the study cohort before stratification to perform physical activity (aOR 1.12–1.16 vs 1.12) and receive at least one general physical examination in the past 3 years (aOR 1.26–1.30 vs 1.27), which suggested that both health practices were independent of age. We also carried out a stratification analysis by chronic disease status (Table 8). Nurses in HPH hospitals had a similar tendency as in the study cohort before stratification to perform physical activity (aOR 1.11–1.16 vs 1.12) and participate in health-promoting activities (aOR 1.12–1.21 vs 1.15), which suggested that both health practices were affected by the HPH effect, and not by the presence or absence of chronic disease. On the contrary, nurses in the HPH hospitals received at least one general physical examination in the past 3 years (aOR 1.17 ~ 1.30) and fecal occult blood test in the past 2 years (aOR 2.19 ~ 2.70) irrespective of their chronic disease status.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that nurses in HPH hospitals were more likely to have better health practices, including health behavior (physical activity and five portions of fruits and vegetables), health screening, and health-promoting activity provided by hospitals when compared to those in non-HPH hospitals in Taiwan. In addition, the interaction between HPH status and individual differences (sex/age/chronic disease) was significant, meaning that associations between HPH status and health practices differed in those with different conditions of sex/age/chronic disease. Finally, our study suggested that nurses who worked in HPH hospitals were more likely to have better health practices, regardless of gender, age, or chronic disease.

In comparison to the general population or other hospital staff, nurses seemingly displayed poorer health-related behaviors and lifestyles3,19,21,22. The poorer health-related behavior and lifestyle of nursing professionals could be partially explained by gender differences23. In the United States, 47.9 percent of adults participated in moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity of at least 150 min per week or 600 MET-minutes per week in 202024. About 52.7% Taiwanese population achieves 600 MET minutes per week, with 61% in males and 44.8% in females25. However, we found that only 12.27% of Taiwanese nurses do 30-min brisk walking of at least 5 days per week, with 19.5% in males and 12.1% in females. Despite the male nurses are better at physical activity than female nurses, the rate did not meet the recommendation and was obviously lower than the Taiwanese general population. Besides physical activity, our research also indicated that male nurses are more likely to participate in sports-related clubs and use gym or sports equipment when compared to female nurses. Interestingly, both male and female nurses who work in HPH tend to have better health practices than those in non-HPH settings. Considering that nurses represent the largest occupational group in hospitals, there is a pressing need to enhance health-promoting initiatives in hospitals and improve the health-promoting practices of nurses, especially female nurses. To encourage participation, female-specific sports-related equipment and clubs could be provided for female nurses.

HPH status and age/chronic disease status were found to be considered simultaneously to predict health practices among nurses3,19. Nurses who were aged 40 and above in HPH were more likely to engage in health behaviors, participate in health screening, and join health-promoting activities facilitated by hospitals than those who were aged below 40 years in non-HPH settings. Additionally, nurses who had a chronic disease in HPH were more likely to participate in cancer screening and join health-promoting activities provided by hospitals when compared to those without chronic disease in non-HPH settings. Given the relationship between increasing age and the prevalence of chronic disease, the positive impact of HPH status on health practices appeared to be similar when stratified by age or baseline chronic disease. Our result further indicated that the interaction between age and baseline chronic disease was associated with health practices among nurses. Nurses who were 40 years of age or older, regardless of their chronic disease status, exhibited a higher likelihood of engaging in healthy practices. It is noteworthy that nurses who were less than 40 years of age and had a chronic disease demonstrated a higher likelihood of engaging in any cancer screening practice, while this group of nurses exhibited a lower likelihood of engaging in certain health behaviors such as exceeding 30 min of walking and consuming five portions of fruits and vegetables a day (see Supplementary Table S1). It implies that younger nurses tend to seek health checks only when they experience a health problem. These findings highlight the importance of considering individual differences, such as age and baseline chronic disease, when promoting health practices among nurses. Healthcare organizations and policymakers should consider tailoring interventions based on individual characteristics to encourage and support health practices among healthcare professionals.

Research suggests that nurses who exhibit healthy behaviors themselves are more likely to provide information about such behaviors to their patients9,10,11,12,13. In our study, most nurses reported having undergone a general physical examination within the past three years and consuming at least five portions of fruits and vegetables on at least one day during the past week. However, the rates of participation in hospital-based health-promoting activities during the past year were low (7.5–24.7%) among nurses, regardless of HPH status. Overall, male nurses, elder nurses, and nurses with chronic diseases were more likely to participate in hospital-based clubs or groups related to sports and weight control, particularly in HPH. These findings can inform policymakers in designing appropriate activities for male nurses, elder nurses, and nurses with chronic diseases, while also increasing incentives for female nurses, younger nurses, and nurses without chronic diseases to participate in such activities and promote healthy habits for themselves and their patients.

Limitation

The cross-sectional study design is limited in establishing a causal relationship. The data were self-reported, which may not exclude a recall bias and response bias. We have no information on nurses who refused to participate in this study, which may have a selection bias. Only 461 male nurses were recruited in this study (1.77%). Hence, our results were probably underpowered to detect the small differences in health-related behaviors between male nurses who worked in HPH or in non-HPH. The questions regarding the physical activities and consumption of fruit and vegetables were not measured using participants' actual habits.

Conclusions

This study suggests the effectiveness of implementing health promotion hospital programs on the health practices of full-time nursing staff in hospitals. To promote the health practice of nurses, their workplace could participate HPH network and provide policies and a supportive environment regarding health promotion to improve nurses’ health. To increase health-promoting activities provided by hospitals and health behavior in female nurses, female-specific lectures, equipment, and clubs could be provided to increase their motions to participation. Male nurses, elder nurses, and nurses with chronic diseases are more likely to have health-related behaviors. Appropriate activities could be designed for male nurses, elder nurses, and nurses with chronic disease and incentives could be increased for female nurses, younger nurses, and nurses without chronic disease to further drive them and their patients to have healthy habits. Future studies can apply a longitudinal design to further examine the effect of HPH status on changes in health practice over time among nursing staff.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Health Promotion Administration, Taiwan (ROC) but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the corresponding author Li-Yin Chien upon reasonable request if permission is granted by the Health Promotion Administration, Taiwan (R.O.C.).

References

Wilson, B. R. & Wagner, D. I. Developing organizational health at the worksite. Am. J. Health Stud. 13(2), 105 (1997).

Taiwan HPH Network. WHO-certified Health Promoting Hospitals in Taiwan. The International HPH Network, 2016. About HPH (2016).

Chiou, S. T., Chiang, J. H., Huang, N. & Chien, L. Y. Health behaviors and participation in health promotion activities among hospital staff: Which occupational group performs better?. BMC Health Serv. Res. 14(1), 474 (2014).

Douglas, F. et al. Promoting physical activity in primary care settings: Health visitors’ and practice nurses’ views and experiences. J. Adv. Nurs. 55(2), 159–168 (2006).

Joyce, C. M. & Piterman, L. The work of nurses in Australian general practice: A national survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 48(1), 70–80 (2011).

Su, S. Y. et al. Association between Pap smear screening and job stress in Taiwanese nurses. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 20, 119–124 (2016).

Whitehead, D. Health promoting hospitals: The role and function of nursing. J. Clin. Nurs. 14(1), 20–27 (2005).

Ruston, A. Interpreting and managing risk in a machine bureaucracy: Professional decision-making in NHS Direct. Health Risk Soc. 8(3), 257–271 (2006).

Albert, F. A., Crowe, M. J., Malau-Aduli, A. E. O. & Malau-Aduli, B. S. Physical activity promotion: A systematic review of the perceptions of healthcare professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(12), 4358 (2020).

Fie, S., Norman, I. J. & While, A. E. The relationship between physicians’ and nurses’ personal physical activity habits and their health-promotion practice: A systematic review. Health Educ. J. 72(1), 102–119 (2013).

Kelly, M., Wills, J. & Sykes, S. Do nurses’ personal health behaviours impact on their health promotion practice? A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 76, 62–77 (2017).

Mujika, A., Arantzamendi, M., Lopez-Dicastillo, O. & Forbes, A. Health professionals’ personal behaviours hindering health promotion: A study of nurses who smoke. J. Adv. Nurs. 73(11), 2633–2641 (2017).

Zhu, D. Q., Norman, I. J. & While, A. E. The relationship between doctors’ and nurses’ own weight status and their weight management practices: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 12(6), 459–469 (2011).

Zhu, D. Q., Norman, I. J. & While, A. E. Nurses’ self-efficacy and practices relating to weight management of adult patients: A path analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 10, 131 (2013).

Lee, C. B. et al. Strengthening health promotion in hospitals with capacity building: A Taiwanese case study. Health Promot. Int. 30(3), 625–636 (2015).

Lee, C. B., Chen, M. S. & Chu, C. M. The health promoting hospital movement in Taiwan: Recent development and gaps in workplace. Int. J. Public Health 58(2), 313–317 (2013).

Lee, C. B., Chen, M. S., Powell, M. & Chu, C. M. Achieving organizational change: Findings from a case study of health promoting hospitals in Taiwan. Health Promot. Int. 29(2), 296–305 (2014).

Lin, Y. W. & Lin, Y. Y. Health-promoting organization and organizational effectiveness of health promotion in hospitals: A national cross-sectional survey in Taiwan. Health Promot. Int. 26(3), 362–375 (2011).

Lo, W. Y., Chiou, S. T., Huang, N. & Chien, L. Y. Medical personnel working in health promoting hospitals have better physical activity and colon cancer screening behaviors. Clin. Health Promot. 9(S2), 36–42 (2019).

Chiou, S. T., Chiang, J. H., Huang, N., Wu, C. H. & Chien, L. Y. Health issues among nurses in Taiwanese hospitals: National survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 50(10), 1377–1384 (2013).

Keele, R. To role model or not? Nurses’ challenges in promoting a healthy lifestyle. Workplace Health Saf. 67(12), 584–591 (2019).

Ross, A., Bevans, M., Brooks, A. T., Gibbons, S. & Wallen, G. R. Nurses and health-promoting behaviors: Knowledge may not translate into self-care. AORN J. 105(3), 267–275 (2017).

George, L. S., Lais, H., Chacko, M., Retnakumar, C. & Krishnapillai, V. Motivators and barriers for physical activity among health-care professionals: A qualitative study. Indian J. Community Med. 46(1), 66–69 (2021).

US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030: Overview and Objectives of Physical Activity. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/physical-activity/increase-proportion-adults-who-do-enough-aerobic-physical-activity-substantial-health-benefits-pa-02.

Health Promotion Administration, Taiwan. The Rate of Insufficient Physical Activity Among Adults Aged 18 Years and Over (2017). https://data.gov.tw/dataset/152379

Funding

This study was originally designed by Shu-Ti Chiou, done by Bureau of Health Promotion, Department of Health, Taiwan, and analyzed by the authors with the support of grant TTMMH-107-07 from Taitung MacKay Memorial Hospital, Taitung, Taiwan. The funding sources were not involved in the study or article preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, H.-H.C., J.C.-Y.L., and L.-Y.C.; Data curation, S.-T.C.; Formal analysis, J.C.-Y.L.; Funding acquisition, J.C.-Y.L.; Investigation, S.-T.C.; Methodology, S.-T.C., N.H., and L.-Y.C.; Supervision, L.-Y.C.; Writing—original draft, H.-H.C., and J.C.-Y.L.; Writing—review and editing, H.-H.C., J.C.-Y.L., S.-T.C., N.H., and L.-Y.C.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, HH., Lai, J.CY., Chiou, ST. et al. The effect of hospital-based health promotion on the health practices of full-time hospital nurses: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 13, 9763 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36873-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36873-z

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.