Abstract

We evaluated the association between maternal prenatal folic acid supplement use/dietary folate intake and cognitive development in 4-year-old offspring (N = 3445) using data from the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Cognitive development was evaluated using the Kyoto Scale of Psychological Development 2001. Multiple regression analysis revealed that offspring of mothers who started using folic acid supplements pre-conception had a significantly higher language-social developmental quotient (DQ) (partial regression coefficient 1.981, 95% confidence interval 0.091 to 3.872) than offspring of mothers who did not use such supplements at any time throughout their pregnancy (non-users). Offspring of mothers who started using folic acid supplements within 12 weeks of gestation had a significantly higher cognitive-adaptive (1.489, 0.312 to 2.667) and language-social (1.873, 0.586 to 3.159) DQ than offspring of non-users. Regarding daily dietary folate intake from preconception to early pregnancy, multiple regression analysis revealed that there was no significant association with any DQ area in the 200 to < 400 µg and the ≥ 400 µg groups compared with the < 200 µg group. Maternal prenatal folic acid supplementation starting within 12 weeks of gestation (but not adequate dietary folate intake from preconception to early pregnancy) is positively associated with cognitive development in 4-year-old offspring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Folate is important for fetal neurodevelopment and an essential cofactor in DNA, RNA synthesis, and DNA methylation processes 1,2. Folate is also essential for the development of neural tubes in the first 4 weeks of pregnancy, and previous studies have established that supplementation with folic acid, which is the synthetic form of folate, in mothers reduces the risk of neural tube defects 3,4,5. Previous studies have also suggested that prenatal folic acid supplementation or adequate dietary folate intake may be beneficial for the cognitive development of pregnant women’s offspring 1,2,6,7.

In a study based on the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS) database, adequate maternal dietary folate intake from preconception to early pregnancy was positively associated with verbal cognitive development in 2-years-old offspring 8. However, in the same study, maternal prenatal folic acid supplement use was not significantly associated with verbal or nonverbal cognitive development in 2-years-old offspring 8.

The association between maternal prenatal folic acid/folate intake and neurodevelopment of the offspring may change as the offspring grow 1,2,7. Therefore, continuous evaluation of offspring growth is necessary. In this study, we evaluated the association between maternal prenatal folic acid supplement use/dietary folate intake and cognitive development in 4-year-old offspring using the JECS database.

Experimental methods

Ethical approval

The JECS protocol has been previously published 9,10. The JECS protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ministry of the Environment Institutional Review Board on Epidemiological Studies (No. 100910001) and the Ethics Committees of all participating institutions. The JECS was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and other national regulations and guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Informed consent was obtained from a parent or a legal guardian for participants below 20 years old.

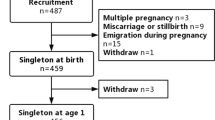

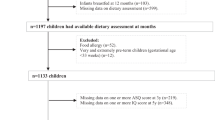

From the JECS Main Study, we extracted data from the Sub-Cohort Study, which comprised 5% of the participating offspring who were randomly selected and met the eligibility criteria 11. Of 100,148 children in the JECS Main Study, children born after April 1, 2013, met the eligibility criteria. (1) all questionnaire and medical record data from offspring and their mothers collected from the first trimester to 6 months of age, (2) biospecimens (except umbilical cord blood) from children and their mothers collected in the first to second/third trimester and delivery were randomly selected for each Regional Centre at regular intervals. Of 10,302 selected offspring, 5017 participated. Face-to-face assessment of neuropsychiatric development, body measurement, pediatrician’s examination, blood/urine collection for clinical testing and chemical analysis, and home visits (ambient and indoor air measurement and dust collection) are conducted. Face-to-face assessment of neuropsychiatric development conducted by trained personnel via the Kyoto Scale of Psychological Development 2001 (KSPD) for 4-year-old offspring 11. The profiles of the participating mothers, fathers, and offspring did not substantially differ between the main and Sub-Cohort Studies11. For the present study, we used the jecs-ta-20210401 dataset, which was released in April 2021 and revised in February 2022. The dataset contains the cognitive developmental results of 4-year-old offspring in the form of KSPD scores. Multiple-birth offspring were excluded from the study because we wanted to focus on offspring from singleton pregnancies.

Design and participants

The JECS is a nationwide, prospective, birth cohort study involving 100,000 mother–offspring pairs, started in 20119,10. It is ongoing and is planned to continue until the offspring turn 18. Trained examiners evaluated the cognitive development of approximately 5000 offspring selected for the Sub-Cohort Study of the JECS 11. The dataset of 4-years-old offspring’s test results was provided to us in 2021.

We followed the same method as we did for our previous study in which we used the Kyoto Scale of Psychological Development 2001 (KSPD) on 2-year-old offspring 8. The main differences were that we used the KSPD data of 4-year-old offspring and evaluated sex differences.

Exposure: maternal folic acid supplement use

The Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in Japan recommends the intake of 400 µg/day of supplementary folic acid for pregnant women and women intending to become pregnant 12. A face-to-face interview was conducted with pregnant women to assess their use of folic acid and other supplements 13,14. In this study, multivitamin supplements were not considered folic acid supplements, as we did not have data on the contents of each multivitamin supplement.

Participants were classified into four groups, based on the time of initiation of folic acid supplementation: (1) preconception users (started before conception), (2) early post-conception users (within 12 weeks of gestation), (3) late post-conception users (after 12 weeks of gestation), and (4) non-users (non-use of folic acid supplements before conception and during gestation).

Exposure: maternal dietary folate intake

A semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) was used to estimate participants’ dietary folate intake from foods 13. The FFQ comprises a list of foods with standard portion sizes commonly consumed in Japan 15. The validity of the FFQ for the estimation of dietary folate intake in Japan has previously been established 15. The FFQ consisted of 172 food and beverage items and nine frequency categories, ranging from almost nothing to seven or more times per day for food and 10 or more glasses per day for beverages. Thereafter, the intake of 53 nutrients was calculated.

The mother’s FFQ was administered during the first and second trimesters of gestation, at a median of 14.6 (interquartile range: 12.0–17.9) weeks of gestation. Participants reported their frequency of food consumption over the previous year.

The FFQ was not designed to estimate folic acid 13,15. The Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in Japan recommends an estimated average requirement for total dietary folate, for example, from natural food sources, as follows: an intake of ≥ 200 µg/day for adult women and ≥ 400 µg/day for pregnant women 12. Therefore, the study participants were classified into three groups, according to daily dietary folate intake (< 200 µg, 200 µg to < 400 µg, and ≥ 400 µg).

Outcome: psychological development of 4-year-old offspring

The KSPD is a standardized developmental assessment tool for Japanese children, covering cognitive-adaptive and language-social areas 16,17. These areas correspond to nonverbal and verbal cognitive development, respectively. Scores are combined to form the developmental quotient (DQ; in days), which is calculated by dividing the developmental age (in days) by the chronological age (in days) and multiplying the quotient by 100. To ensure reliability of administration of the KSPD, the interviewers were trained and certified by the JECS. Administrative procedures and evaluations were strictly standardized to ensure inter-interviewer reliability.

Statistical analysis and covariables

We compared the mothers’ characteristics and their offspring’s cognitive developmental data via analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s range test. Sex differences were also examined. Multiple regression analyses were used to assess the association between maternal prenatal folic acid intake/dietary folate intake and offspring psychological development.

First, multiple regression analyses were adjusted for maternal age at delivery, maternal body mass index (kg/m2) before pregnancy, infertility treatment, unexpected pregnancies, parity, marital status, maternal highest level of education, paternal highest level of education, maternal smoking status during pregnancy, paternal smoking status during pregnancy, maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy, annual household income (× 103 yen/year) during pregnancy, pregnancy complications, obstetric labor complications, mode of delivery, maternal neuropsychiatric disorders, and a six-item maternal Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6) score ≥ 5 during pregnancy18,19,20. Adjustments were also made for the sex of the offspring (not for subgroup analysis), the offspring’s birth weight, gestational week of delivery, breastfeeding at 18 months postpartum, family structure, maternal job status after delivery, day care center attendance, multivitamin supplement use, iron preparation use, and trace element use. Dietary intake (measured with the FFQ) included energy content and nutrients, including amino acids, n − 3 unsaturated fatty acids, Fe, Ca, vitamin A, vitamin B12, and vitamin C. No multicollinearity was observed in the multiple regression analysis. For reference, the parity and number of the offspring’s siblings were confirmed to be multicollinear. The total energy, protein, and Zn contents were also confirmed to be multicollinear.

Second, multiple regression analyses were adjusted for variables selected using a stepwise method.

All analyses were significant at a 0.05 probability of significance and were performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

We analyzed the records of 3445 offspring out of the 104,059 records in the dataset (Fig. 1). Table 1 summarizes the participants’ characteristics. The maximum dietary folate intake in the ≥ 400 µg/day group was 2956 µg/day.

Folic acid supplements

The results of the ANOVA and Tukey’s range test for maternal folic acid supplement use and the KSPD score of the offspring are summarized in Table 2.

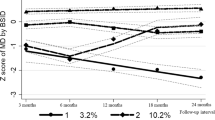

Overall, the multiple regression analysis without the stepwise method revealed significantly higher scores for cognitive-adaptive DQ among early post-conception users (partial regression coefficient [B]: 1.489, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.312 to 2.667, standardized partial regression coefficient [β]: 0.046, P = 0.01) than among non-users (Table 3). There was also a significantly higher score for language-social DQ among the preconception (B: 1.981, 95% CI 0.091 to 3.872, β: 0.036, P = 0.04) and early post-conception (B: 1.873, 95% CI 0.586 to 3.159, β: 0.052, P = 0.004) users than among non-users (Table 3). The multiple regression analysis with the stepwise method revealed significantly higher scores for cognitive-adaptive DQ among early post-conception users (B: 1.595, 95% CI 0.430 to 2.760, β: 0.049, P = 0.01) than among non-users (Table 3). There was also a significantly higher score for language-social DQ among the preconception (B: 2.122, 95% CI 0.273 to 3.972, β: 0.039, P = 0.02) and early post-conception (B: 1.932, 95% CI 0.718 to 3.145, β: 0.054, P = 0.002) users than among non-users (Table 3).

In male offspring, the multiple regression analysis without the stepwise method revealed significantly higher score for language-social DQ was observed among preconception (B: 3.316, 95% CI 0.606 to 6.026, β: 0.061, P = 0.02) and early post-conception (B: 2.377, 95% CI 0.405 to 4.350, β: 0.062, P = 0.02) users than among non-users (Table 3). The multiple regression analysis with the stepwise method that revealed significantly higher score for language-social DQ was observed among preconception (B: 3.666, 95% CI 1.057 to 6.275, β: 0.068, P = 0.01) and early post-conception (B: 2.646, 95% CI 0.807 to 4.485, β: 0.069, P = 0.005) users than among non-users (Table 3).

In female offspring, the multiple regression analysis without the stepwise method revealed significantly higher score for cognitive-adaptive DQ was observed among early post-conception users (B: 1.670, 95% CI 0.104 to 3.236, β: 0.055, P = 0.04) than among non-users (Table 3). The multiple regression analysis with the stepwise method that revealed significantly higher score for cognitive-adaptive DQ was observed among early post-conception users (B: 1.673, 95% CI 0.211 to 3.135, β: 0.055, P = 0.02) than among non-users (Table 3).

Dietary folate intake

The results of the ANOVA and Tukey’s range test for maternal dietary folate intake and the KSPD score of offspring are summarized in Table 4.

Overall, the multiple regression analysis without the stepwise method revealed no significant association with any DQ score in the 200 µg to < 400 µg group or the ≥ 400 µg group compared with the < 200 µg group (Table 5). The multiple regression analysis with the stepwise method revealed no significant association with any DQ score in the 200 µg to < 400 µg group or the ≥ 400 µg group compared with the < 200 µg group (Table 5).

In male and female offspring, the multiple regression analysis without the stepwise method revealed no significant associations with any DQ score in the 200 µg to < 400 µg group and the ≥ 400 µg group compared with the < 200 µg group (Table 5). The multiple regression analysis with the stepwise method revealed no significant associations with any DQ score in the 200 µg to < 400 µg group and the ≥ 400 µg group compared with the < 200 µg group (Table 5).

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that the offspring of mothers who started prenatal folic acid supplement use within 12 weeks of gestation exhibited better nonverbal and verbal cognitive development at age 4 than did those with mothers who did not use folic acid supplements. However, offspring of mothers with an adequate daily dietary folate intake from preconception to early pregnancy did not exhibit better nonverbal or verbal cognitive development at age 4 than did offspring of mothers with inadequate folate intake in that period. These results are inconsistent with those of our previous study on 2-year-old offspring 8.

First, our previous study of 2-year-old offspring 8 demonstrated that the offspring of mothers who took ≥ 200 µg folate per day from preconception to early pregnancy had a significantly higher DQ in the language-social area than did those in the < 200 µg group. Moreover, the DQ was higher in the ≥ 400 µg group than in the 200 to < 400 µg group. However, this study revealed that the beneficial association was no longer present in 4-year-olds. This suggests that the benefit of maternal dietary folate intake during early pregnancy on the offspring’s verbal cognitive development may last for up to approximately 2 years, and that postnatal environment factors may offset the difference between groups by the time the offspring are 4 years of age.

Second, regarding maternal prenatal folic acid supplementation, previous studies 8 and the current study were limited by the lack of detail on the amount of folic acid in the supplements used and the frequency of use. Our previous study of 2-year-old offspring revealed no significant association between starting prenatal folic acid supplement use within 12 weeks of gestation and verbal or nonverbal cognitive development. However, to our surprise, such associations were observed for 4-year-old offspring in this study. In Japan, only approximately 30% of pregnant women seem to start using folic acid supplements before conception or within 12 weeks of gestation 14. Therefore, pregnant women who use folic acid supplements may be more conscious of their future offspring’s health than women who do not 21,22,23. We hypothesize that mothers who use folic acid supplements in early pregnancy for their offspring’s health will exhibit enthusiastic parenting behavior after delivery. The effects of enthusiastic postpartum parenting behavior may become apparent when the offspring reach the age of 4. In support of this hypothesis, a cohort study in the Netherlands 24 revealed that there was no association between plasma folate concentrations in pregnant women and autistic traits in their offspring, but that prenatal folic acid use was associated with fewer autistic traits in the offspring at age 3. They suggested that prenatal folic acid supplement use, a marker of good health literacy, is associated with many health-conscious behaviors that decrease the background risk of autistic traits in offspring. To substantiate our hypothesis, the next task would be to analyze the relationship between maternal prenatal folic acid supplement use and postpartum parenting behavior.

In this study of 4-year-old offspring, we also explored sex differences in the effect of folic acid supplementation/dietary folate intake. Male offspring of mothers who started using folic acid supplements before conception or within 12 weeks of gestation exhibited better verbal cognitive development than those of mothers who did not use such supplements. However, no significant association was observed with nonverbal cognitive development. Female offspring of mothers who started using folic acid supplements within 12 weeks of gestation exhibited better nonverbal cognitive development than those of mothers who did not use such supplements. However, no significant association was observed with verbal cognitive development. In animal studies, sex differences have been demonstrated in maternal folic acid loading and behavior in offspring 25,26; however, few reports on such sex differences have been made for human studies. The reason for the observed sex difference in human offspring is unknown, and further investigation is required.

For reference, we compared our results to those of previous cohort studies on prenatal folic acid/dietary folate intake and cognitive development in offspring from 3 to 6 years of age3. Maternal supplement use of more than 600 µg/day and folate intake from food in early pregnancy were positively associated with receptive language development in 3-year-old offspring in a US cohort study 27. Maternal folic acid supplement use from the eighth week of pregnancy was associated with a reduced risk of severe language delay in 3-year-old offspring in a Norwegian cohort study 28. In a US cohort study, the use of periconceptional folic acid supplements was not associated with language development in 3-year-old offspring 29. In a Spanish cohort study, a positive association between maternal use of folic acid supplements at the end of the first trimester and social competence, verbal skills, and verbal-executive skills was observed in 4-year-old offspring. However, no differences in perceptive performance or memory were observed in that study 30. In a European, multicenter, randomized controlled trial, the maternal use of 400 μg/day folic acid supplement from the 20th week of pregnancy until delivery had no significant effect on the cognitive function of 6.5-year-old offspring 31. Moreover, a study in the US revealed that the folate nutritional status of mothers in the latter half of pregnancy, assessed via plasma and erythrocyte folate concentrations, had no impact on the cognitive development of 5-year-old offspring 32.

This section discusses the overall importance of folate/folic acid in pregnancy. Because the fetus receives folate from the mother through the placenta, pregnant women’s folate/folic acid intake must be adequate. Folate deficiency in pregnant women can cause megaloblastic anemia 1. Low folate status in pregnant women increases the risk of preterm delivery, low birth weight, fetal growth retardation, congenital heart disease, and structural malformations such as oral clefts 1. It has also been suggested that maternal folate deficiency may result in neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia in their offspring 1. It is also well known that supplementation with folic acid, a synthetic form of folate, reduces the prevalence of folate deficiency during pregnancy and that folic acid supplementation during gestation reduces the risk of neural tube defects (NTD) in the fetus3,4,5.

Besides folate/folic acid, other nutrients, such as protein, zinc, iron, vitamins, and long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid, are also important for offspring’s neurodevelopment 33,34,35. The nurturing environment after birth is also important. Therefore, factors other than those we have included as confounding factors in this study may also likely play a role in children’s neurodevelopment. Further comprehensive evaluations that include folate/folic acid and these factors are needed.

This study had some limitations. The first limitation was the retrospective collection of information for maternal supplement use, which in the case of the preconception period was at least 10–16 weeks before the interviews; this may not have been very accurate. Second was the lack of detailed information on the use of folic acid supplements and whether the supplements used by all of the study participants contained the same amount of folic acid. In Japan, folic acid supplements are manufactured by various companies, but pregnant women and women planning to conceive are recommended to supplement their diet with 400 μg/day of folic acid, not exceeding 1000 μg/day 12. Thus, although not all pregnant women necessarily received the same dose of folic acid, each likely consumed at least 400 μg/day.Third, there was no accurate information on how long women took folic acid supplements during preconception or pregnancy. Fourth, the fact that dietary folate intake was self-reported via the FFQ. Fifth, there was no information on reliable biochemical indicators of folate status, such as red blood cell folate concentration, in the JECS study.

However, the study’s strength was in the objective investigation of the offspring’s cognitive development by trained interviewers.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that maternal prenatal folic acid supplement use starting within 12 weeks of gestation was associated with higher verbal and nonverbal cognitive development in 4-year-old offspring than not using such supplements. However, there were sex differences in this association. Offspring of mothers with an adequate daily dietary folate intake from preconception to early pregnancy were not at an advantage in terms of verbal and nonverbal cognitive development at 4 years of age.

Data availability

Data are unsuitable for public deposition due to ethical restrictions and legal framework of Japan. It is prohibited by the Act on the Protection of Personal Information (Act No. 57 of 30 May 2003, amendment on 9 September 2015) to publicly deposit the data containing personal information. Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Research enforced by the Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare also restricts the open sharing of the epidemiologic data. All inquiries about access to data should be sent to: jecs-en@nies.go.jp. Te person responsible for handling enquiries sent to this e-mail address is Dr. Shoji F. Nakayama, JECS Programme Office, National Institute for Environmental Studies.

References

Naninck, E. F. G., Stijger, P. C. & Brouwer-Brolsma, E. M. The importance of maternal folate status for brain development and function of offspring. Adv. Nutr. 10, 502–519 (2019).

Li, M., Francis, E., Hinkle, S. N., Ajjarapu, A. S. & Zhang, C. Preconception and prenatal nutrition and neurodevelopmental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 11, 1628 (2019).

Kancherla, V., Wagh, K., Priyadarshini, P., Pachón, H. & Oakley, G. P. Jr. A global update on the status of prevention of folic acid-preventable spina bifida and anencephaly in year 2020: 30-Year anniversary of gaining knowledge about folic acid’s prevention potential for neural tube defects. Birth. Defects Res. 20, 1392–1403 (2022).

Singer, T. G., Kancherla, V. & Oakley, G. Paediatricians as champions for ending folic acid-preventable spina bifida, anencephaly globally. BMJ Paediatr. Open 6, e001745 (2022).

Aukrust, C. G. et al. Comprehensive and equitable approaches to the management of neurological conditions in low-and middle-income countries-A call to action. Brain. Spine 2, 101701 (2022).

Chen, H. et al. Neurodevelopmental effects of maternal folic acid supplementation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. On line ahead of print (2021).

Gao, Y. et al. New perspective on impact of folic acid supplementation during pregnancy on neurodevelopment/autism in the offspring children - a systematic review. PLoS ONE 11, e0165626 (2016).

Suzuki, T. et al. Maternal folic acid supplement use/dietary folate intake from preconception to early pregnancy and neurodevelopment in 2-year-old offspring: The Japan environment and children’s study. Br. J. Nutr. 1–24 (2022).

Kawamoto, T. et al. Rationale and study design of the Japan Environment and Children’s study (JECS). BMC Public Health 14, 25 (2014).

Michikawa, T. et al. Baseline profile of participants in the Japan environment and children’s study (JECS). J. Epidemiol. 28, 99–104 (2018).

Sekiyama, M. et al. Study design and participants’ profile in the Sub-Cohort Study in the Japan environment and children’s study (JECS). J. Epidemiol. 32, 228–236 (2022).

Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan. DRIs for folate and folic acid, in Overview of Dietary Reference Intakes for Japanese, 232–237. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10904750/000586553.pdf (2020).

Iwai-Shimada, M. et al. Questionnaire results on exposure characteristics of pregnant women participating in the Japan Environment and children study (JECS). Environ. Health Prev. Med. 23, 45 (2018).

Nishigori, H. et al. Drug use before and during pregnancy in Japan: the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Pharmacy (Basel) 5, 21 (2017).

Yokoyama, Y. et al. Validity of short and long self-administered food frequency questionnaires in ranking dietary intake in middle-aged and elderly Japanese in the Japan public health center-based prospective study for the next generation (JPHC-NEXT) protocol area. J. Epidemiol. 26, 420–432 (2016).

Society for the Kyoto Scale of Psychological Development Test. Shinpan K Shiki Hattatsu Kensahou 2001 Nenban (the Kyoto Scale of Psychological Development Test 2001) (Nakanishiya Shuppan, 2008).

Koyama, T., Osada, H., Tsujii, H. & Kurita, H. Utility of the Kyoto scale of psychological development in cognitive assessment of children with pervasive developmental disorders. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 63, 241–243 (2009).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 60, 184–189 (2003).

Furukawa, T. A. et al. The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 17, 152–158 (2008).

Sakurai, K., Nishi, A., Kondo, K., Yanagida, K. & Kawakami, N. Screening performance of K6/K10 and other screening instruments for mood and anxiety disorders in Japan. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 65, 434–441 (2011).

Obara, T. et al. Prevalence and determinants of inadequate use of folic acid supplementation in Japanese pregnant women: the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (4ECS). J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 30, 588–593 (2017).

Ishikawa, T. et al. Update on the prevalence and determinants of folic acid use in Japan evaluated with 91,538 pregnant women: The Japan environment and children’s study. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 33, 427–436 (2020).

Kikuchi, D. et al. Evaluating folic acid supplementation among Japanese pregnant women with dietary intake of folic acid lower than 480 µg per day: Results from TMM BirThree Cohort Study. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 35, 964–969 (2022).

Steenweg-de Graaff, J. et al. Maternal folate status in early pregnancy and child emotional and behavioral problems: The generation R study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 95, 1413–1421 (2012).

Barua, S. et al. Increasing maternal or post-weaning folic acid alters gene expression and moderately changes behavior in the offspring. PLoS ONE 9, e101674 (2014).

Barua, S., Kuizon, S., TedBrown, W. T. & Junaid, M. A. High gestational folic acid supplementation alters expression of imprinted and candidate autism susceptibility genes in a sex-specific manner in mouse offspring. J. Mol. Neurosci. 58, 277–286 (2016).

Villamor, E., Rifas-Shiman, S. L., Gillman, M. W. & Oken, E. Maternal intake of methyl-donor nutrients and child cognition at 3 years of age. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 26, 328–335 (2012).

Roth, C. et al. Folic acid supplements in pregnancy and severe language delay in children. JAMA 306, 1566–1573 (2011).

Wehby, G. L. & Murray, J. C. The effects of prenatal use of folic acid and other dietary supplements on early child development. Matern. Child Health J. 12, 180–187 (2008).

Julvez, J. et al. Maternal use of folic acid supplements during pregnancy and four-year-old neurodevelopment in a population-based birth cohort. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 23, 199–206 (2009).

Campoy, C. et al. Effects of prenatal fish-oil and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate supplementation on cognitive development of children at 6.5 y of age. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 94(Supplement), 1880S-1888S (2011).

Tamura, T. et al. Folate status of mothers during pregnancy and mental and psychomotor development of their children at five years of age. Pediatrics 116, 703–708 (2005).

Schwarzenberg, S. J. & Georgieff, M. K. Advocacy for improving nutrition in the first 1000 days to support childhood development and adult health. Pediatrics 141, e20173716 (2018).

Cortés-Albornoz, M. C., García-Guáqueta, D. P., Velez-van-Meerbeke, A. & Talero-Gutiérrez, C. Maternal nutrition and neurodevelopment: A scoping review. Nutrients 13, 3530 (2021).

Heland, S., Fields, N., Ellery, S. J., Fahey, M. & Palmer, K. R. The role of nutrients in human neurodevelopment and their potential to prevent neurodevelopmental adversity. Front. Nutr. 9, 992120 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all study participants.

Funding

This study was funded by the Ministry of the Environment, Japan. The findings and conclusions of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors, and do not represent the official views of the above government department.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

The authors’ contributions are as follows: H.N. designed the study. H.N., T.O., T.S., K.I., T.M., H.K., Y.O., A.S., K.S., S.Y., M.H., K.H., and K.F., carried out the study. H.N. and T.N. analyzed the data. H.N., T.N., T.O., T.S., M.M., K.I., T.M., H.K., Y.O., A.S., K.S., S.Y., M.H., K.H., and K.F. interpreted the findings. H.N. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nishigori, H., Nishigori, T., Obara, T. et al. Prenatal folic acid supplement/dietary folate and cognitive development in 4-year-old offspring from the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Sci Rep 13, 9541 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36484-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36484-8

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.