Abstract

Despite economic growth and poverty reduction, under-5 child undernutrition is still rampant in South Asian countries. This study explored the prevalence and risk factors of severe undernutrition among under-5 children in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal for comparison using the Composite Index of Severe Anthropometric Failure. We utilised information on under-5 children from recent Demographic Health Surveys. We used multilevel logistic regression models for data analysis. The prevalence of severe undernutrition among under-5 children was around 11.5%, 19.8%, and 12.6% in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal, respectively. Children from the lowest socioeconomic quintile, and children born with low birth weight were key factors associated with severe undernutrition in these countries. The factors, parental education, maternal nutritional status, antenatal and postnatal care, and birth order were not homogeneous in explaining the determinants of child severe undernutrition across the countries. Our results suggest that the poorest households, and low birth weight of children have significant effects on severe undernutrition among under-5 children in these countries, which should be considered to formulate an evidence-based strategy to reduce severe undernutrition in South Asia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Child undernutrition refers to deficiencies or imbalances in a child’s intake of energy and/or nutrients1. In 2020, approximately 149 million children worldwide aged under five years were estimated to be stunted, with 45 million estimated to be wasted, and 85 million underweight1. About 45% of deaths in children are linked to these conditions1. Severe undernutrition, especially its acute form is a major cause of death in children under five, and severely undernourished children are often too weak to survive childhood morbidities, such as diarrhoea and pneumonia2. Children with severe acute undernutrition are twelve times more likely to die than well-nourished children3. However, the overall prevalence of severe undernutrition and its determinants remain to be elucidated.

South Asia is considered vulnerable for its growing number of under-5 severe undernutrition cases, as two-thirds of affected children live in Asia4. Among the South Asian counties, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal are struggling with a high burden of under-5 severe undernutrition (severe stunting) with the prevalence of 11%, 10%, and 10%, respectively between the year 2010 to 20145,6,7,8. Despite economic growth and poverty reduction, undernutrition is still rampant in South-Asian countries9. This indicates that non-economic factors along with economic development are important. In this study, a nationwide survey from Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal has been used to identify factors that may explain why children under five are severely undernourished.

Under-5 Severe undernutrition is still an issue of discussion. Studies tend to look at disaggregated conventional indicators (e.g., severe stunting, severe wasting, and severe underweight) while it may be better to aggregate these individual indicators8,10,11. Conventional disaggregated indicators are not sufficient for quantifying the overall prevalence of severe child undernutrition which was underreported in the previous studies8,10,11. These conventional indicators partly overlap, and thus do not provide a convincing estimate of the proportion of undernourished children in the population. Further, prevalence estimates by disaggregating indicators cannot comprehensively capture the burden of undernutrition given that children may suffer from more than one form of undernutrition12. The Composite Index of Anthropometric Failure (CIAF) uses conventional undernutrition indicators to provide six different ways of measuring undernutrition13. The overall prevalence of undernutrition was estimated by aggregating conventional undernutrition indicators’ values13. The CIAF, therefore, convincingly, and inclusively estimates the overall proportion of undernourished children in the population13. The Composite Index of Severe Anthropometric Failure (CISAF) in this study has been estimated by using six disaggregated conventional severe undernutrition indicators following the methodological approach of CIAF that provides a convincing estimate of the overall prevalence of severe undernutrition14.

Previous studies have identified several maternal, child, contextual and few environmental factors associated with severe undernutrition measured by the CIAF in Bangladesh, India, and other developing countries15,16,17,18,19. However, the CISAF was used to measure severe undernutrition in Bangladesh, and certain factors were found to be associated with this condition20,21. Further, no previous study used CISAF to explore the prevalence and complex interplay between individual, community, public policy, and environmental risk factors of under-5 severe undernutrition in other South Asian countries including Pakistan and Nepal. Further, available studies used fixed-effect model such as binary logistic regression analysis to identify the determinants of undernutrition or severe undernutrition20,21. However, no previous studies addressed the possibility of both community- and household-level effects on severe undernutrition measured by the CISAF in Bangladesh, Pakistan, Nepal as well as other South Asian countries. The present study has considered already known aetiology to identify the associated factors of severe undernutrition as per the CISAF taking into account multilevel random effect (community-, household- and individual- level effects), investigating the change of direction of these factors using more recent data, might help revise important policy decision-making. Therefore, multilevel binary logistic regression with a random intercept was used to identify various factors related to under-5 child severe undernutrition in Bangladesh, Pakistan and Nepal including any community and household variations on severe undernutrition.

Methods

Data source and study plan

The Demographic Health Surveys (DHS) are nationally representative household sample surveys that collect population data, health and nutrition, and socioeconomic and anthropometric indicators, emphasising maternal and child health. The DHS is modular in structure, and in addition to the core questionnaire, a set of country-relevant sections and country-specific variables are included. The DHS provides data with standardised variables across surveys. These surveys are administered by ICF International and are nationally representative cross-sectional surveys in low- and middle-income countries22.

The DHS used a two-stage stratified sampling technique. Each country was divided into regions, and populations within these regions were stratified by urban and rural areas of residence. Within these stratified areas, enumeration areas were randomly selected based on the most recent population census. In the first stage, primary sampling units were selected from enumeration areas using the probability proportional to size technique, and samples of households were selected in the second stage using the equal probability systematic sampling technique. In the surveys, women of reproductive age (15–49 years) were interviewed to collect children’s information, such as the demography and environment; health and nutrition; and anthropometric data of children born in the five years preceding the interview included. This multistage sampling technique including its sampling weight helps reduce potential sampling bias. Further, the survey interviewers interviewed all ever-married women aged 15–49 years from the pre-selected households without replacement and change in the implementing stage to prevent selection bias22. The response rates of interviews in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal were 99%, 95%, and 96% respectively.

To allow cross-country comparisons, we restricted the samples to the three latest surveys—Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) 2017–18, Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (PDHS) 2017–18, and Nepal Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) 2016, resulting in information on 7902 children under five years of age in Bangladesh, 4227 in Pakistan, and 2379 in Nepal, capturing a period between 2016 and 2018 (Table S1). A detailed list of the survey years by country can be found elsewhere23,24,25.

Outcome variables

The primary outcome of this study was severe undernutrition among under-5 children, which was measured using the CISAF14. A child was considered to be severely stunted (too short stature for age), severely wasted (severely thin for height) and severely underweight (very low weight for age) if the height-for-age, weight-for-height, and weight-for-age indices were three or more Standard Deviations (SDs) below the WHO Child Growth Standards median26.

Severe undernutrition indicators for under-5 children were categorized into seven groups: (A) no severe failure; (B) severe wasting only; (C) severe wasting and severe underweight; (D) severe wasting, severe stunting, and severe underweight; (E) severe stunting and severe underweight; (F) severe stunting only; and (Y) severe underweight only (Supplementary Table 2). If children belonged to group (A)—i.e., no severe failure, they were categorized as having no anthropometric failures; otherwise, they were categorized as having any anthropometric failure (i.e., the group from B to Y) (Table S2).

Independent variables

The potential independent variables were considered based on previous studies5,6,8,27,28,29, and the availability of the dataset. The potential variables were selected from three levels of characteristics: (i) parental characteristics—maternal age (in years) (≤ 24, 25–29, 30–34, ≥ 35), parents’ educational status ((both parents were uneducated (no formal education)), only father was uneducated, only mother was uneducated, both parents were educated), mother’s income-earning status (currently not working, currently working), underweight mother (no, yes), mother received antenatal care (no, yes), mother received postnatal care (no, yes), women’s attitude toward inmate partner violence (not justified, justified), mother’s decision-making autonomy (no, yes); (ii) child characteristics were, for example, children’s age (0–11 months, 12–23 months, 24–35 months, 36–47 months, 48–59 months), sex of child (male, female), birth order (first, second, third, fourth and above), low birth weight (no, yes, not weighted), and child morbidity (no, yes); (iii) household characteristics—source of drinking water (improved, unimproved), solid fuel used in cooking (clean fuel, solid fuel), type of toilet facility (improved, unimproved), mass media exposure (no, yes), wealth index (poorest, poorer, middle, richer, richest), and contextual factors—place of residence (urban, rural) and region of residence (varies for three countries) (see Table S3 for detailed descriptions).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to present the background characteristics of the children. Since more than 5% missing cases were found in most of the important independent variables (such as, mother received antenatal care, postnatal care, low birth weight etc.) across datasets of three countries, the background characteristics of included and excluded participants were compared and tested if missingness is completely at random (MCAR) using Little’s test, as well as the presence of covariate-dependent missingness30,31. We then performed complete case analysis. Covariate-dependent missingness was handled by including those covariates in the models. Bivariate analysis (Chi-square test) was used to explore the associations between the covariates and severe undernutrition among under-5 children. In three countries, variables that were found to be significant at the level p < 0.10 in bivariate analysis were included in the multivariable analysis20,32,33,34. In DHS, individuals are nested within households and households are nested within communities, which indicate that individuals, households, and communities are not independent of each other35,36. This type of data is usually analysed using a multilevel random intercept model to account for variation in different levels. Therefore, to determine the association between the selected independent variables and the outcome (severe undernutrition as per the CISAF), a multilevel binary logistic regression model with a random intercept term at the community- and household-level were performed. The level of significance for multilevel logistic regression analysis was set at p < 0.05, and an odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was estimated to determine the associated factors. Stata version 17 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas) was used for all analyses considering the complex nature of the sampling weight of all the DHSs. To control the effect of the complex survey design, all bivariate and multivariable analyses of this study were performed using Stata’s “svyset” and melogit commands respectively.

Model evaluation

The predictive performance (discrimination power) of three multivariable statistical models for three countries respectively, was evaluated by calculating the area under the receiver operation curve (ROC) analysis that determines the accuracy of the models in the prediction of under-5 child severe undernutrition.

Ethical approval

The data were collected from secondary sources that do not need ethical approval. Informed consent was obtained verbally from each mother of children (every married woman aged 15–49 years) before being enrolled in the study.

Results

Background characteristics of the study participants

Complete cases or included participants identified for Bangladesh, Pakistan and Nepal were 4617, 2673, and 1919 respectively (Table S4). The background characteristics of included participants were compared with those who were excluded from this analysis due to missing information on outcomes or covariates. The Little’s test for MCAR based on the significance level (p < 0.001) confirmed that the missingness in parents’ educational status, mothers received antenatal and postnatal care, mother’s decision-making autonomy, solid waste and low birth weight (in three countries) were not completely at random. In addition, covariate-dependent missingness was observed; the excluded children were more like to be older age, male, rural settlers and from poor households (Table S5). The findings suggest that the covariates used in the covariate-dependent missingness test could be considered in the final model as well as other important factors might be considered in the complete case analysis.

Furthermore, more than 70% of mothers of children were less than 30 years of age in Bangladesh and Nepal and it was around 53% in Pakistan (Table S4). Parents with no formal education were reported at 50% (22.6 + 27.4) in Pakistan whereas it was around 31.4% and 6% in Nepal and Bangladesh, respectively. More than 45% of children belonged to the socio-economically poorest households in Pakistan and Nepal, and it was 42.3% in Bangladesh. Two-thirds (66.4%) of the children were rural residents in Bangladesh whereas more than half of the children (54%) were in Pakistan and 42.4% in Nepal. Also, more than 50% of the children were less than 2 years of age and were male in the three countries. Detailed information regarding children’s background characteristics is presented in Table S4.

Prevalence of under-5 severe undernutrition

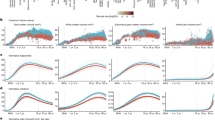

Severe stunting, wasting, and being underweight were approximately 9.1%, 2.0% and 4.1% respectively in Bangladesh. Similarly, they are 1.7%, 2% and 7.5% in Pakistan; and 1.2%, 2% and 5% in Nepal respectively (Fig. 1). In the case of a single form, only severe stunting showed a higher percentage in three countries (for example, Bangladesh: 6.4%, Pakistan: 10.1%, and Nepal: 6.7%) whereas the multiple concurrent forms of severe stunting and severe underweight showed higher percentage than other concurrent forms of severe undernutrition (Bangladesh: 2.2%, Pakistan: 5.7% and Nepal: 2.7%) (Fig. 1).

The prevalence of severe child undernutrition based on the CISAF was 11.4%, 19.8%, and 12.6% in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal, respectively. In Bangladesh, the prevalence was higher among children of parents with no formal education (21.6%), mothers who did not receive antenatal care (18.3%), and children born with low birth weight (18.1%). In Pakistan, a higher prevalence of severe undernutrition was found among children from the poorest households (38%), mothers who did not receive antenatal care (34.4%), and children of parents with no formal education (32%). In Nepal, the prevalence of severe undernutrition was higher among children of the oldest mothers (≥ 35 years) (23.2%), mothers who did not receive antenatal care (25.6%), and children of fourth and above birth order (23.1%) (Table 1).

Regional variations in the prevalence

In Bangladesh, severe undernutrition was highly prevalent among under-5 children in the North-East region (Sylhet division) (13.2%) and the prevalence was lower in the South-West region (Khulna division) (7.8%) (Fig. S1). In Pakistan, the prevalence of severe undernutrition was higher in the South-West region (Baluchistan) (32.4%) and was lower in the North-East region (Federal Capital Territory) (10.2%) (Fig. S2). Again, in Nepal, severe undernutrition was highly prevalent in the mid-Western Development region (Karnail province) (21.5%) and was lower in the Far-Western Development Region (Sudurpashchim province) (10.2%) (Fig S3).

Associated factors of under-5 child undernutrition

All multilevel logistic regression models presented in Table 2 were statistically significant (likelihood-ratio χ2 = 113.53, P < 0.001 for Bangladesh; likelihood-ratio χ2 = 285.14, P < 0.001 for Pakistan; and likelihood-ratio χ2 = 56.98, P < 0.001 for Nepal)35,36. The analysis results also showed that the variances of the community and household effects were significant for severe undernutrition measured by CISAF in all three countries with a p value of < 0.001 (Table 2).

In Bangladesh, the important factors for severe child undernutrition were: children born with low birth weight (OR 5.36, 95% CI 2.80–10.29, p < 0.001), versus normal weight; children of age group 24–35 months (OR 3.16, 95% CI 2.05–4.86, p < 0.001) versus children of age group 0–11 months; children from the lowest socio-economic quintile (OR 2.51, 95% CI 1.14–5.48, p < 0.001) versus the upper socio-economic quintile; and children of parents with no formal education (OR 2.14, 95% CI 1.33–3.45, p = 0.002) versus both parents with formal education (Table 2).

Similarly, in Pakistan, children from the lowest socio-economic quintile (OR 21.13, 95% CI 4.84–92.19, p < 0.001) versus the upper socio-economic quintile; children born with low birth weight (OR 23.34, 95% CI 5.60–97.23, p < 0.001) vs. healthy weight; children less than 3 years of age (24–35 months) (OR 8.76, 95% CI 4.03–19.05, p < 0.001) versus children of age group 0–11 months; mothers of oldest age group (20–24 years) (OR 0.15, 95% CI 0.06–0.43, p < 0.001) versus the youngest age group (≤ 24 years); children of parents with no formal education (OR 2.49, 95% CI 1.07–5.79) vs. children of parents with formal education were identified key factors associated with severe undernutrition (Table 2).

Further, important factors identified in Nepal were children from the lowest socio-economic quintile (OR 4.43, 95% CI 1.38–14.27, p = 0.013) vs. the upper socio-economic quintile; children of fourth and above birth order (OR:2.96, 95% CI 1.14–7.64, p < 0.001) vs. first order children; children born with low birth weight (OR 2.77, 95% CI 1.23–6.26, p = 0.014) versus healthy weight; and children of underweight mothers (OR 2.22, 95% CI 1.25–3.95, p = 0.006) (Table 2).

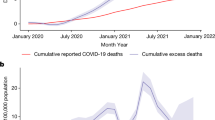

Predictive performance

Figure 2 described the predictive performance of the three models. The area under the ROC curves for Bangladesh, Pakistan and Nepal were 0.683, 0.730 and 0.711 respectively, indicating the models’ performance in predicting under-5 severe undernutrition was low.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study that investigates factors from different levels/perspectives concerning severe undernutrition as per the CISAF taking into account community- and household-level variations for Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal. The study revealed that the overall prevalence of under-5 severe undernutrition was 11.4%, 19.8%, and 12.6% in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal, respectively. Evidence from 39 low- and middle-income countries showed an average of 20% of severe undernutrition cases were recorded while applying the CISAF method14. In the South Asian region, the prevalence of severe undernutrition in India is one of the highest, accounting for more than 16%, based on conventional disaggregated indicators, such as severe stunting, severe wasting, and severe underweight37. However, the overall prevalence of severe undernutrition will be higher according to the measurement of the CISAF because it accounts for all forms of anthropometric failure. According to the present findings, the South Asian countries, likes Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal were not very successful in reducing severe child undernutrition. One of the possible reasons could be that there is a lack of coordination between different key sectors. Therefore, coordination between key institutions, for example, government institutions, academic, research and training institutions, and national/international non-governmental organizations is necessary along with addressing other associated factors38.

In estimating prevalence, a higher prevalence of severe undernutrition was not shared by the same variable. It differed by children’s parents with no formal education, children from the poorest households, and children of the oldest mothers aged ≥ 35 years in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal, respectively. On the other hand, the lowest socio-economic quintile, and children born with low birth weight were found to be potential factors associated with severe child undernutrition and common in the three countries, respectively. The findings from the present study are in line with previous studies suggesting that the poorest household have significant effects on under-5 severe undernutrition as per the CISAF in Bangladesh and as per the conventional disaggregated indicators in Pakistan, and Nepal5,11,20,21,39,40. Earlier evidence also suggests that the reduction in childhood undernutrition is greater when both the mother and father had higher socioeconomic status40. Investing in women’s education, maternal and child healthcare resources and increasing participation of underprivileged people in income-generating activities might be a key to improving the nutritional status of children. Our study also found that children born with low birth weight had a higher chance of severe undernutrition in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal. Few studies in developing countries assessed low birth weight as a key risk of severe undernutrition using the disaggregated conventional indicator and using CISAF in Bangladesh irrespective of community- and household-level variations20,21,29,41. Generally, children who are born with a low birth weight gain inadequate amounts of height and weight42. Thus, they may remain shorter and lighter and might suffer from severe undernutrition without adequate nutritional support. More advanced and up-to-date guidelines for antenatal and postnatal care need to be developed and essentially ensured following the guideline by the healthcare provider and mothers that might help to reduce childhood severe undernutrition in those countries.

This study reveals that parental education and children aged 24–35 years of age were found to be associated with severe undernutrition based on the CISAF in Bangladesh and Pakistan whereas mothers’ underweight was associated with severe undernutrition in Bangladesh and Nepal. On top of that, mothers who received postnatal care and children of fourth and above birth order were identified as important correlates of severe undernutrition in Bangladesh and Nepal respectively. The overall burden of severe undernutrition and its distinct factors were not widely articulated while considering community- and household-level variations in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal. However, the education status of mothers, maternal nutritional status, and birth order have previously been found to be significantly associated with severe acute (wasting) and chronic (stunting) undernutrition in different low and middle-income countries irrespective of community- and household-level variations43,44,45,46. The present study suggested that various factors associated with severe undernutrition as per the CISAF acted differently across these three South Asian countries and the associated odds ratio (or the magnitude of the risk) varied while considering composite index with community- and household-level variations. Despite sharing similar cultural boundaries, sharp contrasts are appearing in these countries in terms of demography, social context, geography, health, and environment47,48. Higher and varied wealth education-based inequalities exist in countries like Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal47. In brief, the emerging and varied threats to population structure, society, education, economics, urbanization, environment, geography, and health care might prevent the improvement of the nutritional status of children in the South Asian region, particularly in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal47,48. It is important to consider factors at local, regional, and potentially global levels that help the process of formulating strategies and policies on a transnational basis to reduce severe undernutrition. The present study also suggests introducing community-based management of severe undernutrition for large numbers of children to receive effective nutritional and clinical care in various settings41.

A composite index combines multiple indicators of undernutrition (e.g., severe stunting, wasting and underweight) into a single summary measure which provides a more comprehensive and accurate picture of the nutritional status of a population than any single indicator alone. Single indicators can be affected by measurement error. For example, the prevalence of coexistence of stunting and wasting is the interaction term of stunting and wasting49,50. Combining multiple indicators into a composite index reduces measurement error and increases the accuracy of undernutrition estimates. While a single indicator may only capture one type of undernutrition, composite index captures different types of undernutrition such as chronic (stunting) and acute (wasting and underweight) undernutrition that can aid in improving the effectiveness of nutritional interventions by targeting multiple forms of undernutrition simultaneously and can have a greater impact on improving children’s health and well-being.

The use of three different national representative household survey data points with a high response rate was a strength of this study. The survey questions and instruments were validated and well-established. A wide range of potential factors from the parental, household, and child perspectives has been used in logistic regression models concerning severe undernutrition among children aged under five years based on the CISAF. In addition, the results from this study are generalizable for Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal, and even for other South Asian countries, because the large sample size accounts for the population across the three countries. However, there are limitations to the study. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, it was not possible to establish a causal relationship. Diet practice, ethnicity, and parental behavioural factors were not controlled for in this study due to the lack of availability of this information. Another limitation is that information bias can occur because the survey data was collected by self-reporting information.

Conclusion

Using the recent Demographic Health Surveys from Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal, our results suggest that children from the poorest households and children born with low birth weight were key factors associated with severe undernutrition. Introducing cost-effective community-based program with a focus on poor and marginalized populations might help reduce under-5 severe undernutrition in South Asian countries. Although the composite index provides a comprehensive scenario, still it is not a popular method in application among demographers and nutritionists. Further extensive research on composite indexing might help to address the high burden of under-5 severe undernutrition comprehensively.

Data availability

The data underlying the results presented in the study are publicly accessible and available from the DHS website (https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm). The name of the datasets are Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS), Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (PDHS) 2017–18, and Nepal Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) 2016.

Abbreviations

- BDHS:

-

Bangladesh demographic and health survey

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CIAF:

-

Composite index of anthropometric failure

- CISAF:

-

Composite index of severe anthropometric failure

- DHS:

-

Demographic health surveys

- NDHS:

-

Nepal demographic and health survey

- PDHS:

-

Pakistan demographic and health survey

References

WHO. Malnutrition. World Health Organization (WHO) Switzerland: Geneva (2021).

Trehan, I. et al. Research article (New England Journal of Medicine) Antibiotics as part of the management of severe acute malnutrition. Malawi Med. J. 28(3), 123–130 (2016).

McDonald, C. M. et al. The effect of multiple anthropometric deficits on child mortality: Meta-analysis of individual data in 10 prospective studies from developing countries. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 97(4), 896–901 (2013).

Organization WH. Management of severe acute malnutrition in infants and children (2018).

Chowdhury, M. R. K. et al. Socio-demographic risk factors for severe malnutrition in children aged under five among various birth cohorts in Bangladesh. J. Biosoc. Sci. 53(4), 590–605 (2021).

Tiwari, R., Ausman, L. M. & Agho, K. E. Determinants of stunting and severe stunting among under-fives: Evidence from the 2011 Nepal demographic and health survey. BMC Pediatr. 14(1), 1–15 (2014).

Aurangzeb, B. et al. Prevalence of malnutrition and risk of under-nutrition in hospitalized children. Clin. Nutr. 31(1), 35–40 (2012).

Islam, M. R. et al. Reducing childhood malnutrition in Bangladesh: The importance of addressing socio-economic inequalities. Public Health Nutr. 23(1), 72–82 (2020).

Organization WH. Levels and trends in child malnutrition: UNICEF (2021).

Bhandari, R., Khatri, S. K. & Shrestha, K. B. Predictors of severe acute malnutrition among children aged 6 to 59 months attended out patient therapeutic program Center in Kavre District of Nepal-a case control study. Int. J. Child Health Nutr. 7(1), 30–38 (2018).

Sand, A. et al. Determinants of severe acute malnutrition among children under five years in a rural remote setting: A hospital based study from district Tharparkar-Sindh, Pakistan. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 34(2), 260 (2018).

Vollmer, S. et al. The association of parental education with childhood undernutrition in low-and middle-income countries: Comparing the role of paternal and maternal education. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46(1), 312–323 (2017).

Nandy, S. et al. Poverty, child undernutrition and morbidity: New evidence from India. Bull. World Health Organ. 83, 210–216 (2005).

Vollmer, S. et al. Levels and trends of childhood undernutrition by wealth and education according to a composite index of anthropometric failure: Evidence from 146 demographic and health surveys from 39 countries. BMJ Glob. Health 2(2), e000206 (2017).

Islam, M. S. & Biswas, T. Prevalence and correlates of the composite index of anthropometric failure among children under 5 years old in Bangladesh. Matern. Child Nutr. 16(2), e12930 (2020).

Kundu, R. N. et al. Factor associated with anthropometric failure among under-five Bengali children: A comparative study between Bangladesh and India. PLoS ONE 17(8), e0272634 (2022).

Chowdhury, M. R. K., Khan, H. T. & Mondal, M. Differences in the socio-demographic determinants of undernutrition in children aged< 5 years in urban and rural areas of Bangladesh measured by the composite index of anthropometric failure. Public Health 198, 37–43 (2021).

Permatasari, T. A. E. & Chadirin, Y. Assessment of undernutrition using the composite index of anthropometric failure (CIAF) and its determinants: A cross-sectional study in the rural area of the Bogor District in Indonesia. BMC Nutr. 8(1), 133 (2022).

Fenta, H. M., Zewotir, T. & Muluneh, E. K. Space–time dynamics regression models to assess variations of composite index for anthropometric failure across the administrative zones in Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 22(1), 1–11 (2022).

Chowdhury, M. R. K. et al. Prevalence and correlates of severe under-5 child anthropometric failure measured by the composite index of severe anthropometric failure in Bangladesh. Front. Pediatr. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2022.978568 (2022).

Anik, A. I. et al. Urban-rural differences in the associated factors of severe under-5 child undernutrition based on the composite index of severe anthropometric failure (CISAF) in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health 21(1), 1–15 (2021).

USAID. Sampling and Household Listing Manual: Demographic and Health Survey (DHS). U S Agency for International Development ICF International (2012).

NIPORT. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2017–18. National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), and ICF Dhaka (2020)

NIPS. Pakistan demographic and health survey 2017–18. National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) and ICF International (2018).

MOHP. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP), New ERA, and ICF International, Calverton, Maryland (2017)

World Health Organization. WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/Height-for-Age, Weight-for-Age, Weight-for-Length, Weight-for-Height and Body Mass Index-for-Age: Methods and Development (World Health Organization, 2006).

Kumar, R. et al. Prevalence and factors associated with underweight children: A population-based subnational analysis from Pakistan. BMJ Open 9(7), e028972 (2019).

Akombi, B. J. et al. Stunting and severe stunting among children under-5 years in Nigeria: A multilevel analysis. BMC Pediatr. 17(1), 1–16 (2017).

Mukuku, O. et al. Predictive model for the risk of severe acute malnutrition in children. J. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 1–7 (2019).

Little, R. J. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 83(404), 1198–1202 (1988).

Groenwold, R. H. et al. Missing covariate data in clinical research: when and when not to use the missing-indicator method for analysis. CMAJ 184(11), 1265–1269 (2012).

Bursac, Z. et al. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol. Med. 3(1), 1–8 (2008).

Thiese, M. S., Ronna, B. & Ott, U. P value interpretations and considerations. J. Thorac. Dis. 8(9), E928 (2016).

Kim, J. How to choose the level of significance: A pedagogical note. SSRN Electron. J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2652773 (2015).

Chowdhury, M. R. K. et al. Risk factors for child malnutrition in Bangladesh: A multilevel analysis of a nationwide population-based survey. J. Pediatr. 172(194–201), e1 (2016).

Chowdhury, M. R. K. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of childhood anemia in Nepal: A multilevel analysis. PLoS ONE 15(10), e0239409 (2020).

Bhadoria, A. S. et al. Prevalence of severe acute malnutrition and associated sociodemographic factors among children aged 6 months–5 years in rural population of Northern India: A population-based survey. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 6(2), 380 (2017).

Saha, K. K. et al. Bangladesh National Nutrition Services: Assessment of Implementation Status (World Bank Publications, 2015).

Seid, A., Seyoum, B. & Mesfin, F. Determinants of acute malnutrition among children aged 6–59 months in public health facilities of pastoralist community, afar region, northeast Ethiopia: A case control study. J. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 1–7 (2017).

Hossain, M. B. & Khan, M. H. R. Role of parental education in reduction of prevalence of childhood undernutrition in Bangladesh. Public Health Nutr. 21(10), 1845–1854 (2018).

Bhutta, Z. A. et al. Severe childhood malnutrition. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 3(1), 1–18 (2017).

Doyle, L. W. Growth and respiratory health in adolescence of the extremely low-birth weight survivor. Clin. Perinatol. 27(2), 421–432 (2000).

Lambebo, A., Temiru, D. & Belachew, T. Frequency of relapse for severe acute malnutrition and associated factors among under five children admitted to health facilities in Hadiya Zone, South Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 16(3), e0249232 (2021).

Ghimire, U. et al. Severe acute malnutrition and its associated factors among children under-five years: A facility-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 20, 1–9 (2020).

Dahal, K. et al. Determinants of severe acute malnutrition among under 5 children in Satar community of Jhapa. Nepal. PloS one 16(2), e0245151 (2021).

Valente, A. et al. Acute and chronic malnutrition and their predictors in children aged 0–5 years in São Tomé: A cross-sectional, population-based study. Public Health 140, 91–101 (2016).

Véron, J. et al. The demography of South Asia from the 1950s to the 2000s. Population 63(1), 9–89 (2008).

King, V. T. Environmental Challenges in South-East Asia (Routledge, 2013).

Garenne, M. et al. Concurrent wasting and stunting among under-five children in Niakhar, Senegal. Matern. Child Nutr. 15(2), e12736 (2019).

Chowdhury, M. R. K. et al. The prevalence and socio-demographic risk factors of coexistence of stunting, wasting, and underweight among children under five years in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nutr. 8(1), 84 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank the DHS program to allow us using the data.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.R.K.C. and M.K. designed the study plan, M.R.K.C. and M.S.R. performed statistical analyses and prepared figures and tables, M.R.K.C., M.K. and M.R. drafted the manuscript, M.A. and B.B. edited it. All authors approved the study and the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chowdhury, M.R.K., Rahman, M.S., Billah, B. et al. Prevalence and factors associated with severe undernutrition among under-5 children in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal: a comparative study using multilevel analysis. Sci Rep 13, 10183 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36048-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36048-w

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.