Abstract

Self-medication (SM) with over-the-counter (OTC) medications is a prevalent issue in Afghanistan, largely due to poverty, illiteracy, and limited access to healthcare facilities. To better understand the problem, a cross-sectional online survey was conducted using a convenience sampling method based on the availability and accessibility of participants from various parts of the city. Descriptive analysis was used to determine frequency and percentage, and the chi-square test was used to identify any associations. The study found that of the 391 respondents, 75.2% were male, and 69.6% worked in non-health fields. Participants cited cost, convenience, and perceived effectiveness as the main reasons for choosing OTC medications. The study also found that 65.2% of participants had good knowledge of OTC medications, with 96.2% correctly recognizing that OTC medications require a prescription, and 93.6% understanding that long-term use of OTC drugs can have side effects. Educational level and occupation were significantly associated with good knowledge, while only educational level was associated with a good attitude towards OTC medications (p < 0.001). Despite having good knowledge of OTC drugs, participants reported a poor attitude towards their use. Overall, the study highlights the need for greater education and awareness about the appropriate use of OTC medications in Kabul, Afghanistan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Self-medication (SM) has been described as “the taking of drugs, herbs or home remedies on one's own initiative, or on the advice of another person, without consulting a doctor”1. This can include purchasing medications directly from pharmacies, reusing formerly prescribed medicines, or buying over-the-counter (OTC) medications from pharmacies or medical stores2. The most commonly self-prescribed medications include analgesics, antipyretics, sedative drugs, specific antibiotics, supplements, herbal medicines, and homeopathic remedies2. Adolescent athletes may also consume nutritional supplements like proteins and amino acids, which may complicate the SM phenomenon3.

SM is a global issue and may contribute to the human pathogen resistance to antibiotics1. One concern about SM is stockpiling, which can lead to a shortage of important drugs that may be needed to treat other serious conditions4. Studies conducted on SM shows that it is a very common practice, especially in economically destitute communities1. Various factors can lead to the practice of SM, including the need for self-care, sympathy for ailing family members, scarcity of healthcare services, low economic status, ignorance, assumption, excessive advertisements of drugs, and availability of drugs in places other than pharmacies5.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the issue of SM globally. Fear and anxiety surrounding the pandemic6, difficulty in accessing healthcare services due to lockdowns7, and misinformation about COVID-19 and potential treatments have all contributed the rise of SM8. Countries in sub-Saharan Africa like Togo do not require a prescription for the purchase of antibiotics and have found an increase in the use of SM to prevent against COVID-19. In a cross-sectional study conducted in Lomé, the capital of Togo, a total of 955 participants were questioned and one-third of the individuals in high-risk populations were found to practice SM9. Another study in Peru questioned 3,792 study respondents about SM during the pandemic and found majority of respondents practiced SM with acetaminophen for respiratory symptoms mainly because they had a cold or flu10. Similarly in Pakistan, the freedom of purchasing pharmaceutical drugs without prescription and the use of unlabeled and unregulated medicinal preparations offered by fake herbalists, homeopaths, and so-called traditional healers has led to misdiagnosis and SM practice11. Globally, SM practice with different OTC medications has seen an increase due to the general population struggle against Coronavirus12. According to a study, global SM practice with different OTC products and antibiotics has increased from 36.2% in 2019 to 60.4% in 20202.

SM is also a prevalent issue in Afghanistan, as demonstrated by a study of 385 participants who visited community pharmacies. The study found that 73.5% of participants had self-medicated with antibiotics, with the top three being penicillin, metronidazole, and ceftriaxone. The primary reasons for SM with antibiotics included economic problems and a lack of time to visit doctors13. Additionally, a study conducted among first- and fifth-year medical students at Kabul University of Medical Sciences found that 25.16% of students reported engaging in SM14. While there is evidence of SM in Afghanistan, the body of literature on the subject remains limited. Therefore, there is a need to further study the issue and bring it to the attention of health policymakers and relevant stakeholders.

The current research was unable to use a paper-and-pencil technique with randomly selected samples due to conflict-related limitations. Instead, it intended to raise awareness of the SM among internet users in Afghanistan who use over-the-counter medicines to provide updated insight for researchers to investigate the topic further and inform health policymakers and other relevant stakeholders.

Results

Demographics of participants

Based on the responses obtained, it was found that 75.2% of the participants were male. The majority of the participants were over 40 years old (95.1%) and single (65.7%). As for occupation and level of education, more participants were from the non-health staff and university level respectively (69.6%, 92.1%). The majority of participants (69.3%) earned more than $100 per month and most of them (97.4%) funded their health expenses by themselves (Table 1).

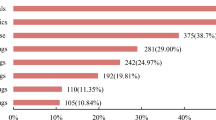

Attitude towards over-the-counter medication

Analyzing the attitude toward OTC medication among the participants, it was found that more than 50% believed that OTC is cheap 80.1% and appropriate to treat minor ailments (75.2%). The average response of participants is 5 over 9 with 53.5% having a good attitude. Based on the threshold cut off number, we assumed 5 score to be considered as good attitude among participants (Table 2).

Knowledge about over-the-counter medication

Assessing the knowledge of the participants with regards to OTC medications, it was found that more than 50% used OTC because they knew what medications can be used to treat themselves (52.4%) and that they read the leaflets before using 62.7%. Moreover, over 90% of respondents agreed that OTC needs prescription and that long-term use of OTC can have side effects (93.6%). The average response of OTC was 5 out of 9 and 65.2% participants were perceived as having good knowledge. Thus, we considered 5 score as good knowledge among participants (Table 3).

Comparison between participants having good or poor knowledge of OTC

Participants with a good knowledge of OTC were significantly from a higher level of education and were health staff (p-value < 0.05) (Table 4).

Comparison between participants having good or poor attitude of OTC

Comparing those who had good attitudes against those having poor attitudes, it was found that those from a higher education level had a statistically better attitude as compared to those having a lower level of education. (p value < 0.05) (Table 5).

Discussion

Afghanistan is a country grappling with numerous challenges, including a long history of conflict and an economy heavily reliant on foreign aid15. The country's healthcare system is strained and lacks sufficient resources, leading many people resorting to SM with OTC medications. The quality of education in Afghanistan is poor, further exacerbating the cycle of poverty. To improve the standard of living in Afghanistan, it is essential to have a responsive government committed to the well-being of its citizens and the nation as a whole, as well as skilled professionals capable of effectively managing the country's challenges. In addition, cooperation with donors can help address the significant gaps in education, economics, and health in Afghanistan.

Before the pandemic, SM was already a significant public health concern in Afghanistan, and the pandemic has only exacerbated the situation, introducing new challenges. In the present study, 65.2% of the participants reported a good knowledge about the use of OTC medications, with those who had a higher level of education reporting even better knowledge. This could be attributed to the multiple studies conducted on SM in Afghanistan, which may have contributed to increased awareness among people and policy implementation13,14. This finding is similar to that reported in Jordan, where a majority of the participants reported good knowledge about the OTC products16. In this study, participants with a higher education degree reported good knowledge. However, in a study conducted in Saudi Arabia, 69.7% of the participants reported poor knowledge, and higher education and employment were found to be statistically significant factors17.

In the present study, more than 90% of respondents agreed that OTC medication needs prescription (96.2%) and that long-term use of OTC can result in side effects. This is similar with a study conducted in Saudi Arabia where the majority of participants reported that analgesic is accompanied by side effects. In this study, participants believed that the causes of analgesic are the result of misuse of the analgesic which are easily obtained without prescription18.

Regarding attitude, nearly half (46.5%) of the participants in this study reported having poor attitude towards OTC medications. This finding is consistent with a study conducted in Asmara, Eritrea, where 44.7% of the participants continued to take drugs despite experiencing health problems19. This could be attributed to socio-economic factors such as poverty, accessibility to healthcare resources, which may impact the attitude of participants.

One reason for SM is for treatment of minor illness. In the present study, 75.2% of the participants self-medicated for this reason. Similar findings have been reported in studies conducted in Eritrea and Thailand. Other reasons for SM included easy access to drugs and cost savings19,20.

The present study reveals that more than 56.8% of the participants used OTC medications because they found the doctors’ fee quite high. In a poor country like Afghanistan, where half of the population lives below poverty line16, it is not surprising that many people cannot afford doctors’ fees and thus seek alternative methods, such as using OTC medications without a prescription. This finding is similar to what has been reported in India, where participants with poor access to healthcare services were more likely to self-medicate and not consult with medical practitioners and use OTC medications21.

In terms of education and financial stability, those participants with a higher level of education and good financial stability reported good knowledge and attitude towards OTC medications. Whereas participants with low level of knowledge and low economic status reported poor attitude and knowledge towards OTC medications. These findings are consistent with those of studies conducted in Greece and Saudi Arabia17,22.

Strengthens and limitations

There are several strengths and limitations to our study. One significant strength was that it was conducted during the pandemic, providing an up-to date understanding of self-medication practices in the country. Additionally, our study identified a significant number of participants who still practice SM, which could be useful for policymakers in implementing timely policies to prevent unnecessary self-medication.

However, the study had several limitations as well. Firstly, it was conducted online, which excluded participants without internet access and may have introduced participation bias toward those with social media access, such as Facebook and WhatsApp. As a result, the study’s findings could be subject to bias. Secondly, the study had a narrow focus, employing a simple questionnaire and only involving the capital city of Kabul. Further research is necessary to examine this topic in other parts of the country. Moreover, the study’s results were affected by an uneven distribution of male participants and university students, which may not accurately represent the population parameters of Kabul. Therefore, more research is needed to determine if this skewed representation is due to the fact that internet and social media usage is more prevalent among university students and graduates. We hope that research institutions, organizations and health authorities who have funding will conduct more in-depth, nationwide research on this issue to gain a better understanding of self-medication practices in Afghanistan.

Conclusion

This study concluded that participants had good knowledge about the use of OTC drugs, but a poor attitude was reported towards them. Therefore, it is recommended that policymakers work towards improving participant’s attitude by implementing new policies and campaigns. In addition, research from other parts of the country is also required to provide a better understanding of the use of OTC drugs in Afghanistan.

Methods

Study population and data collection

An online cross-sectional survey was conducted in Kabul, Afghanistan to assess the knowledge and attitudes towards the use of over-the-counter medication (OTC) among the general public who had access to the internet. The survey was conducted from July to November 2021 through a Google Form link shared via social media platforms such as Facebook (Meta), WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, and Telegram. The questionnaire included a brief background, objective, strategy, voluntary nature of participation, declaration of anonymity and secrecy, instructions for filling out and its submission.

Data were collected online through crowd-sourced convenience sampling based on the availability and accessibility of participants from various parts of the city. The questionnaire was created in English and then translated into Dari, widely spoken in Afghanistan, and verified using face and content validity approaches. Content validity was performed by the expert researchers to ensure the survey was representative of the construct it was intended to assess. Face validity was determined through pilot testing, and changes were made to the questionnaire as needed.

Before completing the questionnaire, participants' were asked for their consent, and 391 (294 male and 97 female) individuals from both rural and urban areas of Kabul were included. Kabul is the capital city of Afghanistan and is diverse and densely populated. The city has become overcrowded due to political upheaval and a lack of opportunity in other parts of the country. The inclusion criteria for this study were adults aged 18 or older living in Kabul who had internet and social media access, regardless of education level or profession, and who agreed to participate voluntarily. Exclusion criteria included individuals under the age of 18 and those living temporarily in Kabul. Sure, we were asked in the survey where people live and exclude those who didn't live at the time of survey. Therefore, the study primarily focused on adult residents of Kabul to determine their attitudes and responses towards consuming drugs without a prescription. A pilot study was conducted to assess the feasibility of the research approach and to confirm that the questionnaire was properly prepared to acquire all the information required. To eliminate uncertainty, the original questionnaire was updated, and repetitive items were removed.

Sampling method

The sample size required for the study was calculated using Krejcie and Morgan’s table. Considering the total number of internet users in Afghanistan 7,337,489 or total population of Kabul city 4,400,000 with 99% CI and 5% margin of error, the sample size calculated was 38523.

Statistical analysis

The data were collected and entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and then entered into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23 for analysis. Simple descriptive analysis was computed for demographic characteristics, and the rest of items were explained in frequency and percentage.

Ethical statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Microbiology Department of Kabul University of Medical Sciences (Approval code: KUMS/ RECMD-193). All processes were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the declaration of Helsinki and subsequent revisions.

Consent to participate

All study participants provided their informed consents to participate in the study before completing the survey.

Data availability

Data cannot be shared publicly because of ethical restriction and respect for anonymity. Data are available upon request from Dr. Arash Nemat, Academic member of Microbiology Department, Kabul University of Medical Sciences via (dr.arashnemat@yahoo.com).

References

Bennadi, D. Self-medication: A current challenge. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 5, 19 (2013).

Arain, M.I., Shahnaz, S., Anwar, R. & Anwar, K. Assessment of Self-medication Practices During COVID-19 Pandemic in Hyderabad and Karachi, Pakistan. Sudan J. Med. Sci. 16, 347–354–347–354 (2021).

Tsarouhas, K. et al. Use of nutritional supplements contaminated with banned doping substances by recreational adolescent athletes in Athens Greece. Food Chem. Toxicol. 115, 447–450 (2018).

Shoaib, A., Babar, M. S., Essar, M. Y., Sinha, M. & Nadkar, A. Infodemic, self-medication and stockpiling: A worrying combination. East. Mediterr. Health J. 27, 438–440 (2021).

Kassie, A. D., Bifftu, B. B. & Mekonnen, H. S. Self-medication practice and associated factors among adult household members in Meket district, Northeast Ethiopia, 2017. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 19, 1–8 (2018).

Chopra, D., et al. Prevalence of self-reported anxiety and self-medication among upper and middle socioeconomic strata amidst COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of education and health promotion 10(2021).

Shrestha, A. B. et al. The scenario of self-medication practices during the covid-19 pandemic; A systematic review. Ann. Med. Surg. (Lond) 82, 104482–104482 (2022).

Gaviria-Mendoza, A. et al. Self-medication and the “infodemic” during mandatory preventive isolation due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 13, 20420986221072376–20420986221072376 (2022).

Sadio, A. J. et al. Assessment of self-medication practices in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak in Togo. BMC Public Health 21, 1–9 (2021).

Quispe-Cañari, J. F. et al. Self-medication practices during the COVID-19 pandemic among the adult population in Peru: A cross-sectional survey. Saudi Pharmaceut. J. 29, 1–11 (2021).

Ali, M. et al. Over-the-counter medicines in Pakistan: Misuse and overuse. The Lancet 395, 116 (2020).

Rafiq, K., et al. Self-medication in the COVID-19 pandemic: survival of the fittest. Disaster Med. Public Health Prepare. 1–5 (2021).

Roien, R. et al. Prevalence and determinants of self-medication with antibiotics among general population in Afghanistan. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 20, 315–321 (2022).

Daanish, A. F. & Mushkani, E. A. Influence of medical education on medicine use and self-medication among medical students: A cross-sectional study from Kabul. Drug Healthcare Patient Saf. 14, 79 (2022).

Essar, M. Y., Ashworth, H. & Nemat, A. Addressing the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan through $10 billion Afghani assets: What are the challenges and opportunities at hand?. Glob. Health 18, 74 (2022).

Taybeh, E., Al-Alami, Z., Alsous, M., Rizik, M. & Alkhateeb, Z. The awareness of the Jordanian population about OTC medications: A cross-sectional study. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 8, e00553–e00553 (2019).

Aljadhey, H., Assiri, G.A., Mahmoud, M.A., Al-Aqeel, S. & Murray, M. Self-medication in Central Saudi Arabia. Community pharmacy consumers' perspectives. Saudi Med J 36, 328–334 (2015).

Raja, M. A. G., Al-Shammari, S. S., Al-Otaibi, N. & Amjad, M. W. Public attitude and perception about analgesic and their side effects. J. Pharm. Res. Int 2020, 35–52 (2020).

Tesfamariam, S. et al. Self-medication with over the counter drugs, prevalence of risky practice and its associated factors in pharmacy outlets of Asmara Eritrea. BMC Public Health 19, 1–9 (2019).

Chautrakarn, S., Khumros, W. & Phutrakool, P. Self-medication with over-the-counter medicines among the working age population in metropolitan areas of Thailand. Front. Pharmacol. 2101 (2021).

Panda, A., Pradhan, S., Mohapatro, G. & Kshatri, J. S. Predictors of over-the-counter medication: A cross-sectional Indian study. Perspect. Clin. Res. 8, 79 (2017).

Kontogiorgis, C. et al. Estimating consumers’ knowledge and attitudes towards over-the-counter analgesic medication in Greece in the years of financial crisis: The case of paracetamol. Pain Ther. 5, 19–28 (2016).

Internet World Stats. Afghanistan Internet Usage. (2021).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.N. wrote the manuscript draft and developed the original idea; KH.R. and MY.E. contributed in the analysis, discussion and proofreading, SH.A., W.M. and MY.M. assisted with the design and distribution of the questionnaire and revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. A.N. is the corresponding author. All authors attest they meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship. All contributing authors provided their consent for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nemat, A., Rezayee, K.J., Essar, M.Y. et al. A report of Kabul internet users on self-medication with over-the-counter medicines. Sci Rep 13, 8500 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35757-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35757-6

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.