Abstract

High vagal nerve activity, reliability measured by HRV, is considered protective in cancer, reducing oxidative stress, inflammation and opposing sympathetic nerve activity. The present monocentric study examines the relationship between HRV, TNM stage, co-morbidity, systemic inflammation and survival in patients who underwent potentially curative resections for colorectal cancer (CRC). Time-domain HRV measures, Standard Deviation of NN-intervals (SDNN) and Root Mean Square of Successive Differences (RMSSD), were examined as categorical (median) and continuous variables. Systemic inflammation was determined using systemic inflammatory grade (SIG) and co-morbidity using ASA. The primary end point was overall survival (OS) and was analysed using Cox regression. There were 439 patients included in the study and the median follow-up was 78 months. Forty-nine percent (n = 217) and 48% (n = 213) of patients were categorised as having low SDNN (< 24 ms) and RMSSD (< 29.8 ms), respectively. On univariate analysis, SDNN was not significantly associated with TNM stage (p = 0.830), ASA (p = 0.598) or SIG (p = 0.898). RMSSD was not significantly associated with TNM stage (p = 0.267), ASA (p = 0.294) or SIG (p = 0.951). Neither SDNN or RMSSD, categorical or continuous, were significantly associated with OS. In conclusion, neither SDNN or RMSSD were associated with TNM stage, ASA, SIG or survival in patients undergoing potentially curative surgery for CRC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) forms an intricate network of connections that maintain homeostasis via tightly regulated sympathetic and parasympathetic outputs1. The Vagus nerve, a major component of the parasympathetic nervous system, is thought to be protective in cancer2,3. Specifically, vagal nerve activity is thought to reduce oxidative stress and inhibit sympathetic nerve output4. Moreover, reduce inflammation via the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway5.

Heart rate variability (HRV) is defined as the variation in time interval between successive heartbeats6. Reported to be a reliable measure of vagal nerve activity7, recent systematic reviews have found an association between HRV and survival outcomes in patients with cancer8,9. Furthermore, HRV has been associated with prognostic factors associated with cancer outcomes including advanced age, co-morbidity, advanced disease stage and systemic inflammation10,11,12,13,14. As such, the basis of this relationship between HRV and survival outcomes in cancer remains unclear.

To date, the majority of studies examining HRV in colorectal cancer (CRC) have been carried out in patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease15,16,17,18. Indeed, there is a paucity of studies examining the relationships between HRV, tumour/host characteristics and survival in patients with potentially curative CRC19. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to examine the relationship between HRV, TNM stage, co-morbidity, systemic inflammation and survival in patients undergoing potentially curative resections for non-metastatic CRC.

Methods

Patients

Consecutive patients who underwent potentially curative resections for colorectal cancer, within NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde (NHSGGC), between April 2008 and April 2018, were identified from a prospectively maintained database. Those patients with a pre-operative ECG, pre-operative assessment of the systemic inflammatory response and had TNM stage I-III disease were assessed for inclusion. Exclusion criteria were as follows; patients without a pre-operative ECG, had no pre-operative assessment of the systemic inflammatory response or had TNM stage IV disease.

Clinicopathological characteristics

Routine demographic details collected included age, sex and BMI. Age categories were grouped into < 64, 65–74 and > 74 years. Patient comorbidity was classified using the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grading system20. The presence of ischaemic heart disease, congestive heart failure and diabetes mellitus specifically was also identified from patients’ medical records10,11. The patient’s pre-operative medication history was identified from anaesthetic assessments and medical records. The cumulative anti-cholinergic burden (AChB) score of mediations was retrospectively calculated and grouped as < 3/ ≥ 321,22. Tumour pathological characteristics including stage, differentiation and the presence of venous invasion were identified from pathology reports. Tumours were staged using the fifth edition of the TNM classification, consistent with practice current in the United Kingdom during the study period23.

The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS). The date and cause of death were confirmed using hospital electronic case records. Date of last recorded follow-up or last review of electronic case records was 21st March 2023, which served as the censor date. This retrospective observational study was approved by the West of Scotland Research Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to surgery. All aspects of this study were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Heart rate variability (HRV)

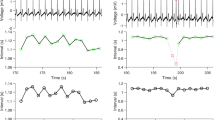

Heart rate variability was analysed using a 12-lead, 10-s (150 Hz) pre-operative ECG performed within the 3 months prior to the date of surgery. If multiple ECG’s were available for the same, the most recent ECG before date of surgery was used for analysis. The time interval in milliseconds (ms) between consecutive R-peaks in lead II was used to calculate time-domain HRV parameters, Standard Deviation of NN-intervals (SDNN) and Root Mean Square of Successive Differences (RMSSD), as previously described19. The R-R time interval was calculated by manually counting the number of small boxes between R waves and multiplying the sum by 40 ms. Measurements of time intervals were performed by two individuals (JM and SL). The median values of SDNN and RMSSD were then calculated and used to categorised into low/high groups.

Patients with pre-operative ECG’s were excluded for the following reasons: patients with cardiac arrhythmias (including atrial and ventricular extrasystole), pacemakers, patients taking beta-blockers, patients with bradycardia (heart rate < 50 bpm) or tachycardia (heart rate > 110 bpm) as previously described19,24.

Systemic Inflammation

The pre-operative systemic inflammatory response was determined using the Systemic Inflammatory Grade (SIG)- a combination of the neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and the modified Glasgow Prognostic Score (mGPS)25. Patients were categorised as grade 0–4, as follows: SIG 0 was defined as mGPS 0 and NLR < 3; SIG 1 as mGPS 0 and NLR 3–5 or mGPS 1 and NLR < 3; SIG 2 as mGPS 0 and NLR > 5 or mGPS 2 and NLR < 3 or mGPS 1 and NLR 3–5; SIG 3 as mGPS 1 and NLR > 5 or mGPS 2 and NLR 3–5 and SIG 4 as mGPS 2 and NLR > 5 (See Supplementary Table 1).

Pre‐operative haematological and biochemical results were identified from medical records and prospectively recorded. Blood samples were either obtained at pre-operative assessment, within 30 days of surgery, for elective patients or on admission for patients undergoing emergency surgery. An autoanalyzer was used to measure serum CRP (mg/L) and albumin (g/L) concentrations (Architect; Abbot Diagnostics, Maidenhead, UK).

Statistical analysis

SDNN, RMSSD, TNM stage, ASA, SIG and OS were presented as categorical variables. Categorical variables were analysed using Chi-square test for linear-by-linear association. For categorical variables, Fisher’s exact test was used when value of single cell of a two-by-two table was n ≤ 5.

The prognostic value of SDNN and RMSSD to OS were examined using univariate and multivariate Cox’s proportional-hazards model. SDNN and RMSSD were presented as both continuous and categorical (median) variables. To examine the relationships between OS and clinicopathological variables, and adjust for potential confounding factors, the authors included any variable showing an association below the significance threshold of p < 0.10 on univariate analysis in the backward conditional multivariate model. A two-sided p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. OS was defined as the time (months) from date of surgery to date of death due to any cause.

Missing data were excluded from analysis on a variable-by-variable basis. Two-tailed p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 27.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient inclusion

Of the 605 patients with CRC cancer, who underwent potentially curative resection during the study timeframe, 166 did not meet the inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1). The clinicopathological characteristics of the included patients are shown in Table 1. The median follow-up was 78 months (IQR 61–99 months) and 31% (n = 137) patients died during the follow-up (see Table 1).

Inter-rater reliability was assessed in a sample of 30 random patient ECG’s, with an inter-class correlation coefficient (ICC) of 1.000. The median SDNN was 24.0 ms (interquartile range, IQR, 17.9–35.8 ms) and 49% (n = 217) of patients were categorised as having a low SDNN (< 24.0 ms). The median RMSSD was 29.8 ms (IQR 23.1–42.2 ms) and 48% (n = 213) of patients were categorised as having a low RMSSD (< 29.8 ms).

The relationship between SDNN (median) and tumour pathology, co-morbidity, systemic inflammation and OS in patients undergoing potentially curative surgery for CRC is shown in Table 2. On univariate analysis, SDNN was significantly associated with RMSSD (p < 0.001). On univariate analysis, SDNN was not significantly associated with age (p = 0.180), sex (p = 0.539), tumour site (p = 0.867), TNM stage (p = 0.830), differentiation (p = 0.935), venous invasion (p = 0.052), ASA (p = 0.598), ischaemic heart disease (p = 0.557), heart failure (p = 0.445), diabetes mellitus (p = 0.921), AChB score (p = 0.071), SIG (p = 0.898) or OS (p = 0.882, see Table 2).

The relationship between RMSSD (median) and tumour pathology, co-morbidity, systemic inflammation and survival in patients undergoing potentially curative surgery for CRC is shown in Table 3. On univariate analysis, RMSSD was significantly associated with AChB score (p < 0.05) and SDNN (p < 0.001). On univariate analysis, RMSSD was not significantly associated with age (p = 0.700), sex (p = 0.323), tumour site (p = 0.183), TNM stage (p = 0.267), differentiation (p = 0.314), venous invasion (p = 0.061), ASA (p = 0.294), ischaemic heart disease (p = 0.219), heart failure (p = 1.000), diabetes mellitus (p = 0.172), SIG (p = 0.951) or OS (p = 0.319, see Table 3). When this analysis was repeated in AChB score < 3 patients were examined, there were no new significant results observed. Therefore, these results were not displayed in detail.

The relationship between OS and TNM stage, ASA, SIG, SDNN and RMSSD is shown in Table 4. On univariate analysis, age (p < 0.001), TNM stage (p < 0.001), ASA (p < 0.001) and SIG (< 0.001) were significantly associated with OS. On multivariate analysis, age (p < 0.001), TNM stage (p < 0.001), ASA (p < 0.05) and SIG (p < 0.05) remained significantly associated with OS (see Table 4). When this analysis was repeated in only patients with TNM stage III disease, this did not lead to any new significant results. Therefore, these results were also not displayed in detail.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present study is the largest to date to examine HRV in patients undergoing potentially curative resections for CRC. Recognised prognostic factors including advanced age, TNM stage, ASA and SIG were all found to be determinants of survival in the present, well-defined cohort confirming the internal validity of observations. However, neither measure of HRV (SDNN or RMSSD) was significantly associated with advanced age, disease stage, co-morbidity, inflammatory status or survival. As such the results are not only informative to the utility of HRV as a prognostic host-assessment in patients potentially curative CRC, but to the basis of the relationship between HRV and survival outcomes in patients with CRC.

Despite a reported association with reduced HRV and CRC outcomes15,18, examination of the prognostic value to survival outcomes specifically is limited. Particularly in patients with potentially curative disease, with the majority of studies including only those with locally advanced or metastatic disease in cohorts also including other tumour types8,9. Therefore, the present negative results add to the existing literature and are consistent with the recent report of Strous and co-workers that found neither measure of HRV was associated with cancer-specific or overall survival in a cohort of 428 patients with primary, non-metastatic colorectal cancer19. The patients included in the two studies were similarly matched in age, sex, co-morbidity, stage of disease and survival. Furthermore, with proportion of patients categorised as having low SDNN and RMSSD (49% and 48%, respectively, in the present study vs. 51% and 54%, respectively, in the previous study by Strous and Co-workers). However, heterogeneity did exist between the studies, with Strous and co-workers employing threshold values to categorise patients into low/high HRV based on previous studies. Furthermore, Strous and co-workers reporting a lower median RMSSD (17.5 ms). Nevertheless, the SDNN and RMSSD values reported in the present study are in keeping with those of other contemporary studies of HRV in patients with CRC16,18 and of other cancer subtypes/disease stages12,18. Therefore, taken together the present evidence suggests that HRV may have limited prognostic value with respect to survival in patients undergoing potentially curative surgery for CRC.

While an association between time-domain HRV measures (SDNN and RMSSD) and survival outcomes in patients with cancer has been reported in systematic reviews8,9, the basis of this relationship remains unclear. One hypothesis is that the vagal nerve is responsible for neuro-immune modulation, improving survival outcomes in cancer by dampening the systemic inflammatory response2,3. A recent study of 272 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer by De Couck and co-workers reported that in patients with longer survival, HRV was inversely associated with a systemic inflammation (CRP)12. However, Cherifi and co-workers, in a study of 202 patients with mainly locally advanced or metastatic ovarian cancer, reported that a low HRV was independently associated with survival when adjusted for inflammatory response (Neutrophil: lymphocyte ratio)26. Furthermore, to date, the majority of studies that reported a significant association between HRV and survival outcomes in cancer have been of patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease12,26,27,28. Given the association of reduced HRV and advanced disease stage13,29, tumour stage may be a major confounding factor to the relationship between HRV and survival9. Indeed, the median SDNN (24.0 ms) and RMSSD (29.8 ms) reported in the present study were higher than those reported by Cherifi and co-workers (Median SDNN 11.1 ms and median RMSSD 11.5 ms26. Therefore, further study across a range of disease stages is required to delineate the potential prognostic value of HRV to survival outcomes in patients with cancer.

There are a number of limitations to the present study. Firstly, the present study was retrospective in nature and therefore may be subject to sample bias. Secondly, the present study only included patients who underwent potentially curative surgery for CRC. Further large comparative studies of HRV across TNM stages, including advanced disease, will be informative to the true relationship between HRV and survival in patients with CRC. Lastly, the present study measured the time-interval between heartbeats manually, which may introduce observer error. This may confound the present observations and explain the absence of an association between time-domain HRV parameters and age, systemic inflammation, cardiac disease and survival in the present study. Nevertheless, measurements using the present methodology showed excellent correlation between observers and SDNN and RMSSD values consistent with other contemporary studies of HRV in patients with CRC16,18. Further studies utilizing automated measurement of time-domain parameters should readily confirm the present observations.

In conclusion, HRV was not significantly associated with TNM stage, co-morbidity, systemic inflammation or survival in this well-defined cohort of patients undergoing potentially curative resection for CRC.

Data availability

Raw data will be made available on request to the senior author (DCM).

References

Gibbons, C. H. in Handbook of Clinical Neurology Vol. 160 (eds Kerry H. Levin & Patrick Chauvel) 407–418 (Elsevier, 2019).

Reijmen, E., Vannucci, L., De Couck, M., De Grève, J. & Gidron, Y. Therapeutic potential of the vagus nerve in cancer. Immunol. Lett. 202, 38–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imlet.2018.07.006 (2018).

De Couck, M., Caers, R., Spiegel, D. & Gidron, Y. The role of the vagus nerve in cancer prognosis: A systematic and a comprehensive review. J. Oncol. 1236787–1236787, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1236787 (2018).

De Couck, M., Mravec, B. & Gidron, Y. You may need the vagus nerve to understand pathophysiology and to treat diseases. Clin. Sci. 122, 323–328. https://doi.org/10.1042/cs20110299 (2011).

Martelli, D., McKinley, M. J. & McAllen, R. M. The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway: A critical review. Auton. Neurosci. 182, 65–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2013.12.007 (2014).

Malliani, A., Pagani, M., Lombardi, F. & Cerutti, S. Cardiovascular neural regulation explored in the frequency domain. Circulation 84, 482–492. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.84.2.482 (1991).

Kuo, T. B., Lai, C. J., Huang, Y. T. & Yang, C. C. Regression analysis between heart rate variability and baroreflex-related vagus nerve activity in rats. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 16, 864–869. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.40656.x (2005).

Zhou, X. et al. Heart rate variability in the prediction of survival in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 89, 20–25 (2016).

Kloter, E., Barrueto, K., Klein, S. D., Scholkmann, F. & Wolf, U. Heart rate variability as a prognostic factor for cancer survival—A systematic review. Front Physiol 9, 623. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.00623 (2018).

Mølgaard, H., Christensen, P. D., Sørensen, K. E., Christensen, C. K. & Mogensen, C. E. Association of 24-h cardiac parasympathetic activity and degree of nephropathy in IDDM patients. Diabetes 41, 812–817. https://doi.org/10.2337/diab.41.7.812 (1992).

Stein, P. K. & Kleiger, R. E. Insights from the study of heart rate variability. Annu. Rev. Med. 50, 249–261. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.med.50.1.249 (1999).

De Couck, M., Maréchal, R., Moorthamers, S., Van Laethem, J. L. & Gidron, Y. Vagal nerve activity predicts overall survival in metastatic pancreatic cancer, mediated by inflammation. Cancer Epidemiol. 40, 47–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2015.11.007 (2016).

Wu, S., Chen, M., Wang, J., Shi, B. & Zhou, Y. Association of short-term heart rate variability with breast tumor stage. Front. Physiol. 12, 678428. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.678428 (2021).

Garavaglia, L., Gulich, D., Defeo, M. M., Thomas Mailland, J. & Irurzun, I. M. The effect of age on the heart rate variability of healthy subjects. PLoS One 16, e0255894. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255894 (2021).

Zygulska, A. L., Furgala, A., Krzemieniecki, K., Wlodarczyk, B. & Thor, P. Autonomic dysregulation in colon cancer patients. Cancer Invest. 36, 255–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/07357907.2018.1474893 (2018).

Mouton, C. et al. The relationship between heart rate variability and time-course of carcinoembryonic antigen in colorectal cancer. Auton. Neurosci. 166, 96–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2011.10.002 (2012).

Gidron, Y., De Couck, M. & De Greve, J. If you have an active vagus nerve, cancer stage may no longer be important. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 28, 195–201 (2014).

De Couck, M. & Gidron, Y. Norms of vagal nerve activity, indexed by heart rate variability, in cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol. 37, 737–741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2013.04.016 (2013).

Strous, M. T. A. et al. Is pre-operative heart rate variability a prognostic indicator for overall survival and cancer recurrence in patients with primary colorectal cancer?. PLoS ONE 15, e0237244. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237244 (2020).

Dripps, R. D., Lamont, A. & Eckenhoff, J. E. The role of anesthesia in surgical mortality. JAMA 178, 261–266. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1961.03040420001001%JJAMA (1961).

Kiesel, E. K., Hopf, Y. M. & Drey, M. An anticholinergic burden score for German prescribers: score development. BMC Geriatr. 18, 239. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0929-6 (2018).

Bengtsson, J., Olsson, E., Igelström, H., Persson, J. & Bodén, R. Ambulatory heart rate variability in schizophrenia or depression: Impact of anticholinergic burden and other factors. J Clin Psychopharmacol 41, 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1097/jcp.0000000000001356 (2021).

Sobin, L. H. & Fleming, I. D. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors, fifth edition (1997). Union Internationale Contre le Cancer and the American Joint Committee on Cancer. Cancer 80, 1803–1804 (1997)https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971101)80:9<1803::aid-cncr16>3.0.co;2-9

van den Berg, M. E. et al. Normal values of corrected heart-rate variability in 10-second electrocardiograms for all ages. Front. Physiol. 9, 1. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.00424 (2018).

Golder, A. M. et al. The prognostic value of combined measures of the systemic inflammatory response in patients with colon cancer: an analysis of 1700 patients. Br. J. Cancer 124, 1828–1835. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-021-01308-x (2021).

Cherifi, F. et al. The promising prognostic value of vagal nerve activity at the initial management of ovarian cancer. Front. Oncol. 12, 1. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.1049970 (2022).

Chiang, J.-K., Kuo, T. B. J., Fu, C.-H. & Koo, M. Predicting 7-day survival using heart rate variability in hospice patients with non-lung cancers. PLoS ONE 8, e69482. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069482 (2013).

Wang, Y. M., Wu, H. T., Huang, E. Y., Kou, Y. R. & Hseu, S. S. Heart rate variability is associated with survival in patients with brain metastasis: A preliminary report. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 503421. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/503421 (2013).

Stone, C. A., Kenny, R. A., Nolan, B. & Lawlor, P. G. Autonomic dysfunction in patients with advanced cancer; prevalence, clinical correlates and challenges in assessment. BMC Palliat Care 11, 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684x-11-3 (2012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M. and D.C.M. wrote the manuscript and analysed the data. S.L., G.M., A.H. and I.K. were involved in data collection and analysis. R.D.D., P.G.H., D.K.C. and N.B.J. were involved in conceptualization and editing of the manuscript. D.C.M. had primary responsibility for final content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McGovern, J., Leadbitter, S., Miller, G. et al. The relationship between heart rate variability and TNM stage, co-morbidity, systemic inflammation and survival in patients with primary operable colorectal cancer. Sci Rep 13, 8157 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35396-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35396-x

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.