Abstract

Many members of the scorpaenid subfamily: Sebastinae (rockfishes and their relatives) exhibit slow growth and extreme longevity (> 100 y), thus are estimated to be vulnerable to overfishing. Blackbelly rosefish (Helicolenus dactylopterus) is a deepwater sebastine whose longevity estimates range widely, possibly owing to different regional levels of fisheries exploitation across its Atlantic Ocean range. However, age estimation has not been validated for this species and ageing for sebastines in general is uncertain. We performed age validation of northern Gulf of Mexico blackbelly rosefish via an application of the bomb radiocarbon chronometer which utilized eye lens cores instead of more traditional otolith cores as the source of birth year Δ14C signatures. The correspondence of eye lens core Δ14C with a regional reference series was tested with a novel Bayesian spline analysis, which revealed otolith opaque zone counts provide accurate age estimates. Maximum observed longevity was 90 y, with 17.5% of individuals aged to be > 50 y. Bayesian growth analysis, with estimated length-at-birth included as a prior, revealed blackbelly rosefish exhibit extremely slow growth (k = 0.08 y−1). Study results have important implications for the management of blackbelly rosefish stocks, as extreme longevity and slow growth imply low resilience to fishing pressure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bathybenthic and abyssal fishes have become increasingly exploited by fisheries in many regions of the world1. These deepwater species often have distinctive and complex life histories, exhibiting slow growth and extreme longevity, sometimes in excess of 100 years, and live in dark, cold, low-productivity habitats1,2,3. This combination of factors makes sustainable management of deepwater fisheries challenging, as they can be particularly susceptible to overfishing and slow to recover once overfished4,5,6. Catches can often be high as a fishery develops and a stock is fished down, but long-term sustainability often necessitates low catches else stocks are rapidly depleted below sustainable levels7. For example, orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus), a deepwater trachichthyid harvested in the south Pacific, has a maximum sustainable yield estimated to be around 2% of unfished biomass given it is extremely long-lived (> 200 y) with low natural mortality8.

Age is a fundamental parameter in population ecology and fisheries science given accurate estimation of population dynamics rates relies on accurate and precise age estimates9,10. Ageing error most frequently materializes as an underestimate rather than an overestimate of true age, resulting in overestimates of growth and productivity11. Furthermore, underestimation of longevity, which is frequently used to estimate natural mortality (M), can result in the overestimation of M, thus overestimation of FMSY, the fishing mortality that produces maximum sustainable yield12,13. Biased age estimates can also propagate as uncertainty in stock assessment models, leading to overestimates of stock productivity and unsustainably high catch levels as management advice14,15,16,17. Therefore, accurate age estimates are vital to effective fisheries management.

Age in bony fishes is typically estimated by enumerating opaque zones in otoliths, with the assumption that opaque zone counts correspond to annual age11. Opaque zones are formed in otoliths due to seasonal differences in fish growth, which results in changes in the deposition of CaCO3 and protein on the otolith and alternating opaque and hyaline zones18. However, these zones are often difficult to distinguish in otolith sections of many deepwater species, which can result in biased ageing or low precision among readers19,20. Therefore, age validation is critical to accurate age estimation and effective management of deepwater fisheries9.

Blackbelly rosefish (Helicolenus dactylopterus), which is also known as bluemouth rockfish in part of its range, is a deepwater sebastine that is broadly distributed across the Atlantic Ocean, including the northern Gulf of Mexico (nGOM) and Mediterranean Sea21, and is commercially and recreationally exploited in U.S. waters and in commercial, multi-species longline fisheries in European Union waters22,23. However, there have been no stock assessments for blackbelly rosefish stocks in any part of its range since the early 2000s24, thus exploitation status is unknown. Previous age and growth studies in different global regions produced longevity estimates ranging widely from 10 to 43 y22,25,26, but ageing methods have yet to be validated for this species. Moreover, it is not uncommon for deepwater sebastines to have longevity estimates > 100 y27, implying a lack of resiliency to fishery exploitation1,2.

The bomb radiocarbon (14C) chronometer has been widely used to validate age estimation in marine fishes11, including many species in the nGOM28,29,30,31. This tool is based on the approximate doubling of atmospheric 14C in the 1950s and 1960s as a result of nuclear weapon testing, with atmospheric bomb 14C subsequently transferred into the ocean as dissolved inorganic carbon, or DIC32,33. The rise and subsequent decline in Δ14C, which is how 14C is typically measured and reported34, was incorporated into the aragonite skeletons of hermatypic corals around the world35, which have been used as reference time series for validating marine fish age estimates. In applying bomb 14C signatures for fish age validation, fish birth year Δ14C values, typically derived from otolith cores, are examined qualitatively or quantitatively for their correspondence to a regional Δ14C reference series33,36.

Successful applications of the bomb 14C chronometer for fish age validation have largely been restricted to species that spend their early life in shelf or epipelagic waters. This is due to the fact that Δ14CDIC declines rapidly below a well-mixed surface layer31,37 and otolith C is largely (70–80%) derived from DIC38. Therefore, otolith cores of deepwater species are often depleted in 14C relative to surface waters39,40,41. The lack of correspondence of otolith core Δ14C values can lead to a conclusion that birth year, hence age, estimates are biased, when in fact the real issue is that Δ14C values in otolith cores reflect fossil C at depth instead of the bomb 14C signal from the well-mixed surface layer31,42,43.

Patterson et al.44 recently reported eye lens cores can be utilized as a source of birth year Δ14C, which may be especially beneficial for deepwater species because eye lenses are composed of metabolic C and nearly all organic C available to deepwater fishes is derived from epipelagic sources45. Additionally, eye lenses, like otoliths, are metabolically inert once formed and grow throughout a fish’s life46,47. Thus, eye lens cores may be an ideal source of birth year Δ14C for deepwater species44, and analysis of eye lens versus otolith core Δ14C values of nGOM deepwater (to 500 m) fishes suggests eye lens Δ14C does in fact match surface Δ14CDIC values48. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to conduct age validation of blackbelly rosefish via application of the bomb 14C chronometer to eye lens Δ14C, as well as to estimate growth, longevity, and natural mortality from ageing data. Results are discussed in the context of blackbelly rosefish population dynamics, assessment, and management in the nGOM and other global regions where the species occurs.

Methods

Sample collection and age estimation

Fisheries-independent blackbelly rosefish samples were collected between 2015 and 2022 in the nGOM (28.55N to 29.39N and 86.50W to 88.02W) with hook and line at depths of 330 to 520 m. Animals were handled in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals under protocols approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol #202111559). Fish were labeled with zip-ties fastened through the buccal and opercular cavities and then placed on ice. Total length (TL) was measured to the nearest mm and each fish was weighed to the nearest g. Sex was determined by macroscopic examination of the gonads. Sagittal otoliths were removed, cleaned of adhering tissue, and stored dry in plastic cell wells. Both eyes were removed from the head, placed in plastic bags, and frozen at − 20 °C.

Fisheries-dependent samples were collected as part of the National Marine Fisheries Service Trip Interview Program (TIP). Port agents measured blackbelly rosefish to the nearest mm TL and the right and left sagittal otoliths were removed and stored dry in paper coin envelopes, and archived at National Marine Fisheries Service facility in Panama City, FL. Subsequently, all nGOM blackbelly rosefish otolith samples stored in the NMFS archives were shipped to the University of Florida Marine Fisheries Laboratory for age and growth analysis.

Left and right sagittal otoliths from fishery-dependent and -independent samples were weighed to the nearest mg. The left sagitta from each fish sample was embedded in epoxy and fixed to a glass slide with a toluene-based mounting medium. An approximately 0.4-mm thick transverse section was cut through the otolith core with a low-speed, diamond-bladed saw. Thin sections were affixed to glass slides with the mounting medium and the surface of the section was coated with the same medium to fill any cracks or abrasions from the sectioning process. Sections were viewed under a dissecting microscope with 25 × magnification and transmitted light to count opaque zones; for counts > 20, the edge of the otolith was observed under greater magnification (up to 60x). Opaque zones were enumerated independently by two experienced readers (WFP and DWC) without knowledge of morphometric data or the other reader’s opaque zone count. Timing of spawning and opaque zone formation in blackbelly rosefish otoliths is unknown, and consistent margin condition identification is difficult for long-lived fish due to compacted growth zones at the otolith margin; therefore, we only report integer age here. The index of average percent error (iAPE) was calculated between readers to assess between-reader precision of opaque zone counts49, and bias plots were constructed to examine trends in opaque zone counts between readers across ages50.

Bomb 14C age validation

A subset of fisheries-independent blackbelly rosefish samples was selected for Δ14C analysis; fisheries-dependent samples were not considered because eye lenses were not available for those samples. All tools, aluminum foil, or vials that came in contact with otolith or eye lens samples were baked at 525 °C for 24 h to remove any residual C from the manufacturing process. Right otoliths were embedded in epoxy, fixed to a glass slide with mounting medium, and a 1.5-mm thick transverse section, centered on the otolith core, was cut with a diamond-bladed, low-speed saw. Sections were rinsed with 1% ultrapure nitric acid, repeatedly flooded with 18.3 ΜΩ cm−1 polished water, and, once dry, affixed to a glass slide with a toluene-based mounting medium. The core of the otolith was identified, and a trench was milled around the core using the automated milling capabilities of a New Wave Research Micromill fitted with a 0.5-mm diameter milling bit. Powdered aragonite generated from milling the trench was removed, leaving the core intact. The core of the otolith was then extracted by milling to a depth of 1.0 mm. The resulting material was weighed and stored in borosilicate glass vials.

The right eye lens of the blackbelly rosefish whose otoliths were cored were also cored for Δ14C analysis. Eyes were thawed and each lens was extracted through an incision made in the cornea. Each lens was then wrapped in aluminum foil and freeze dried for 12 h, which caused the outer laminae of the lens to split and begin flaking. Outer laminae were removed with forceps, targeting a core mass of approximately 0.7 mg. Once extracted, eye lens cores were stored in borosilicate glass vials.

Otolith and eye lens samples were analyzed for Δ14C and δ13C with accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) at the National Ocean Sciences AMS (NOSAMS) facility at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. The resulting data are reported as Δ14C, which is the activity relative to the absolute international standard (base year 1950) corrected for δ13C fractionation and 14C age34. Blackbelly rosefish otolith and eye lens core Δ14C signatures and birth years were superimposed on the regional Δ14C reference series of coral51,52,53,54,55,56, and known-age red snapper otolith30,56 Δ14C values. Blackbelly rosefish birth year was estimated as year of collection—opaque zone count + 0.5 for each sample. Adding the fractional year accounts for the fact that the entirety of the otolith core from the primordium to the beginning of the first annulus was milled, and the target eye lens diameter of 0.7 mg is estimated to correspond to the first year of life as well. Given the mean birth date and the timing of opaque zone formation are not known for nGOM blackbelly rosefish, adding 0.5 y to the estimated birth year accounted for the fact eye lens and otolith core material were formed across some portion of the first year of life.

The fit of otolith core and eye lens core Δ14C signatures to the regional Δ14C reference series was initially evaluated visually to determine which corresponded best with the regional Δ14C reference series. Ageing bias was subsequently assessed by analyzing the eye lens core Δ14C signatures versus estimated birth years with a Bayesian spline model fit to the regional Δ14C reference series. The Bayesian spline model uses a penalized B-spline approach to fit a smooth function through the Δ14C reference series. The B-spline functions are continuous, piecewise polynomial functions (1 and 2) with the resulting smooth function coming from a linear combination of B-splines (3).

where \({B}_{j,k}\left({x}_{i}\right)\) is the B-spline function for the \(j\)’th member of a set of B-splines of order \(k\) (the polynomial degree plus one) evaluated at a given birth year, \({x}_{i}\). Each B-spline function is defined as a linear combination of two B-splines with order \(k-1\) with weights, \({\omega }_{j,k}\), defined at a given birth year value, \({x}_{i}\), for a given knot, \({t}_{j}\), from a sequence of knots \({\varvec{t}}={t}_{j}, \dots , {t}_{q}\). This sequence of knots, \({\varvec{t}}\), is extended, such that \({q}_{\text{extended}}=2*\left(k-1\right)+q\) to ensure that the B-spline functions cover the whole span of the knots. The set of B-splines of a given order, \(k\), and sequence of knots, \({\varvec{t}}\), can be defined as:

where \({a}_{j}\) are the coefficients of the B-spline functions controlling the effect size of the B-spline. Put simply, the B-splines are a series of piecewise functions spanning the range of the birth years with weights that control how much each B-spline matters to each observed birth year. These B-splines are then multiplied by their coefficients, \({a}_{j}\), to fit the set of B-splines to the Δ14C reference series.

Choosing the number of knots can be done arbitrarily but can easily result in overfitting. To prevent overfitting and avoid tuning the number of knots, we chose an arbitrarily high level of knots, 50, and used a random-walk prior to control the smoothing (4).

where a hyperprior is put on the B-spline coefficients, \({a}_{j}\), based on a random walk from the \(j-1\) coefficient with standard normal priors for the first coefficient, \({a}_{1}\), and for the hyperprior standard deviation, \(\tau\). The effect of this random-walk prior is that across a wide range knot numbers the resulting reference series fit is very similar. To assess the accuracy of age estimates, we fit the penalized B-spline to the reference series assuming the expected Δ14C reference series value came from a normal distribution (5).

where \({Y}_{{\text{ref}},i}\) is the observed Δ14C values, \({\widehat{Y}}_{{\text{ref}},i}\) is the expected Δ14C from the penalized B-splines using the observed reference series birth years \({x}_{{\text{ref}},i}\), and \({\sigma }_{\text{ref}}\) is the standard deviation of the observations around the expected values, the reference series process error. The set of penalized B-splines are then used to estimate the expected Δ14C value of the eye lens samples based on the observed birth year, \({x}_{{\text{obs}},i}\).

However, this does not account for systematic ageing bias so the observed birth years, \({x}_{{\text{obs}},i}\), are then adjusted and the expected Δ14C value re-estimated from the penalized B-splines to estimate the posterior of the ageing bias using (6):

where \({Y}_{{\text{obs}},i}\) is the observed Δ14C values for the otolith and eye lens core samples, \({\widehat{Y}}_{{\text{obs}},i}\) is the expected Δ14C values for these samples, \({\sigma }_{\text{obs}}\) is the standard deviation of the observed Δ14C values around the expected (i.e., process error), and \(\delta\) is the ageing bias. We assumed a uniformly flat prior on \(\delta \sim U\left(-\infty ,\infty \right)\). We fit this model with the cmdstanr package57 in R58 using 8 chains, 1,000 warmup iterations per chain, and 125 sampling iterations per chain. The Gelman-Rubin statistic was used to assess chain convergence with values less than 1.1 indicating convergence59. The 95% Bayesian credible interval was computed for the birth year adjustment posterior distribution, and we assessed whether the estimated ageing bias was significantly different than zero via the probability of the maximum a posteriori (MAP) value was zero, with an inference of no bias if \(p\left({\delta }_{\text{MAP}}=0\right)>0.05\).

Following age validation analysis, a linear regression was fitted to the otolith mass (mg) versus estimated age data. This included fishery-independent as well as fishery-dependent samples. Fishery-dependent samples could not be included in the eye lens-based age validation analysis since eye lenses had not been collected from those fish at the time of sampling. Therefore, computing the relationship between otolith mass and age estimates among all samples, including those from fishery-dependent samples, provided some means to assess the plausibility of longevity estimates.

Growth and natural mortality estimation

A von Bertalanffy growth model (VBGM) incorporating length-at-birth60 as a prior was used to estimate blackbelly rosefish growth parameters (7)61,62.

where \({L}_{\infty }\) is the asymptotic length, \({L}_{0}\) is the length-at-birth, k is the Brody growth coefficient, and \({\widehat{l}}_{t,j,VB}\) is the predicted length at age \(t\) derived from opaque zone counts for each otolith \(j\). There were two opaque zone counts for each otolith section, so we assumed the observed age of each individual came from a Student’s T distribution with the true age as a latent parameter (8).

where \({t}_{j,r}\) is the observed age for otolith \(j\) for reader \(r\), \(\nu\) is the degrees of freedom equal to the number of reads, \({\widehat{t}}_{j}\) is the true age, and \({\sigma }_{\text{obs}}\) is a measure of the between-reader error. This separates the ageing imprecision estimated by multiple readers of otolith samples from overall growth variability, \({\sigma }_{VB}\). We assumed that \({\widehat{l}}_{t,j,VB}\) came from a log-Normal distribution with standard deviation, \({\sigma }_{VB}\) (9).

where \({l}_{t,VB}\) is the observed lengths for each sample.

The VBGM was fit in a Bayesian framework in STAN using the rstan package63 in R58. Weakly informative priors were placed on \({L}_{\infty }\), k, \({\sigma }_{VB}\) using the predicted mean from a VBGM fit using maximum likelihood and setting the respective \({\sigma }_{\theta }\) as the mean parameter estimate times a 50% coefficient of variation. A literature search was conducted for the length-at-birth of blackbelly rosefish and an informative log-normal prior was placed on \({L}_{0}\) with a mean of 2.8 mm and a standard deviation of 1.4 mm64. The model was run over 8 chains with a warmup of 5,000 and 500 samples kept per chain. Models were checked for convergence visually with trace plots and by examining the Gelman-Rubin convergence diagnostic, with values < 1.10 indicating model convergence59.

Natural mortality was estimated using the Hamel and Cope65 estimator, which is based on the maximum observed age (10).

where Amax is the maximum observed longevity. Longevity based proxies have been shown to outperform proxies based on growth and environmental parameters13. Thus, mortality estimation was restricted to the Hamel and Cope65 method.

Results

Sample collection and age estimation

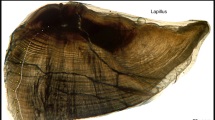

In total, 356 nGOM blackbelly rosefish were sampled, consisting of 255 fisheries-dependent samples, and 101 fisheries-independent samples (Supplementary Fig. S1). Fisheries-independent samples were collected at depths of 338 to 520 m, with a mean depth of 377 m. Depth was not reported for fisheries-dependent samples. Otolith opaque zones were clear but become compacted after the 10th opaque zone (Fig. 1). Opaque zones were enumerated for each individual by both readers. There was no indication of systematic bias in opaque zone counts between reader 1 and reader 2 (Fig. 2) and the between-reader iAPE was 4.5%. Readers agreed on 13.7% of samples and 88.5% were within 5 opaque zones of each other. Otolith opaque zone counts ranged from 8 to 90 for reader 1 and 7 to 94 for reader 2.

Digital image of a 351 mm total length blackbelly rosefish and a blackbelly rosefish otolith section from a 473 mm total length individual estimated to be 90 y by the primary reader. Yellow point denotes the otolith primordium. White points denote every 10th opaque zone, with the 20th through 90th opaque zones denoted in the inset. Red lines outline the approximate area targeted when milling the otolith core.

(A) Primary (WFP) and secondary (DWC) reader otolith opaque zone count comparison (n = 356). Error bars represent the 95% CI about the mean age assigned by reader 2 for all fish assigned a given age by reader 1. Dashed line denotes the 1:1 line of agreement. (B) Distribution of otolith opaque zone count differences between primary (R1) and secondary (R2) readers (n = 356).

Bomb 14C age validation

Thirteen eye lens cores and eleven otolith cores were analyzed for Δ14C. Two otolith cores were broken and lost during processing, hence the mismatch between sample sizes. Otolith opaque zone counts for validation samples ranged from 15 to 63, with resulting birth year estimates ranging from 1956.5 to 2002.5 (Table 1). Otolith cores were considerably depleted in 14C relative to the regional reference series, while the eye lens core Δ14C signatures corresponded well with the reference series (Fig. 3). Thus, age validation analysis was restricted to eye lens core Δ14C. Results of the Bayesian validation analysis (\(p\) = 0.50) demonstrated otolith opaque zone counts provided accurate age estimates for blackbelly rosefish (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3). The Gelman-Rubin convergence diagnostic (1.01 for all parameters) and trace plots indicated the model converged (Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3). There was a significant relationship between otolith mass and age (p < 0.001; R2 = 0.78; Fig. 4), and the residuals were evenly distributed about the regression.

Blackbelly rosefish eye lens (n = 13, red circle) and otoliths core (n = 11, black circle) Δ14C versus the primary reader’s (WFP) year of formation (birth year) estimates overlaid on a regional coral and known-age otolith Δ14C reference series (1940–2021, gray circles). Dashed lines are 95% credible intervals.

Growth and natural mortality estimation

The Bayesian VBGM modeling produced a median growth coefficient (k) estimate of 0.08 y−1. The median L∞ estimate was 399.8 mm, while t0 was estimated to be − 0.10 y, and L0 was 2.95 mm (Table 2, Fig. 5). The Gelman-Rubin convergence diagnostic (< 1.1) and trace plots indicated the model converged (Table 2, Supplementary Fig. S4). Natural mortality was estimated at 0.06 y−1 with the Hamel and Cope65 method, based on maximum observed longevity of 90 y.

von Bertalanffy growth model (VBGM) fitted to blackbelly rosefish age (y) and total length (mm) data. White points with a black border are the primary reader’s (WFP) age estimates and gray points are the secondary reader’s (DWC) age estimates. The median (black solid line) and 95% credible intervals (CI; shaded area) are shown for the model-predicted length at age t (lt) from age-0 to age-94. Posterior distributions and 95% CI (shaded area) of VBGM parameter estimates are shown for asymptotic length (\({L}_{\infty }\)), Brody growth coefficient (k), the theoretical age at which length is 0 (t0), length-at-birth (\({L}_{0}\)), the measure of inter-reader error (\({\upsigma }_{\text{obs}}\)), and the likelihood standard deviation of the VBGM (\({\upsigma }_{VB}\)).

Discussion

Results of eye lens core Δ14C analysis validate blackbelly rosefish otolith opaque zone counts as accurate estimates of age. The observed maximum longevity of 90 y indicates extreme longevity in this species, with correspondingly low natural mortality (M = 0.06 y−1), suggesting blackbelly rosefish stocks may be highly vulnerable to overfishing. Study results also provide a template to validate age estimates of other deep-water marine fishes, which are increasingly exploited1. There is a close relationship between M and the fishing mortality that produces the maximum sustainable yield (\({F}_{MSY}\))12. Therefore, the low level of M for blackbelly rosefish suggests their populations can only sustain minimal fishing mortality, and stocks may not be able to support substantial targeted fisheries long-term. There is not a directed fishery currently for this species in the nGOM (e.g., annual landings of 3.5 metric tons between 2000 and 2021). Nonetheless, its life history suggests conservative management would be prudent there, and especially in global regions where blackbelly rosefish are directly targeted.

In the U.S., blackbelly rosefish are harvested recreationally and commercially in the nGOM and in the Atlantic Ocean, although the fishery in the nGOM is basically a bycatch fishery. As a result, the nGOM stock is not heavily exploited, averaging approximately 3.5 mt landed per year since 2000. Conversely, the Atlantic stock has experienced a rapid increase in exploitation since 2000, particularly in the recreational sector. Landings have increased from approximately 6 mt in 2000 to 115 mt in 2021, an 1800% increase. The US Atlantic stock is currently unassessed, but the composition of Atlantic landings sampled in the 1990s had a max age of 30 years, and a much more truncated age distribution than we report for the nGOM22. We cannot evaluate whether recent landings levels in the US Atlantic catch exceed MSY, but the data presented here could be informative for a data-limited assessment of that stock.

Blackbelly rosefish are also exploited but unassessed in the Portuguese Azores and the Mediterranean Sea23,66. Landings estimates in the multispecies bottom longline fishery in the Azores average approximately 350 mt of blackbelly rosefish per year, with over 11,500 mt in total landed between 1985 and 201823. The smaller Mediterranean fishery landed just under 50 mt in 2003 in Catalonia alone66. The low level of natural mortality estimated for GOM fish suggests only low levels of fishing mortality are likely to be sustainable for these stocks. The rapid increase in recreational landings in the U.S. Atlantic and the sustained landings in the Azores and Mediterranean underlie the need for stock assessments to estimate stock status and prevent overfishing.

Accurately estimating age and growth are critical for effective stock assessment and management67. However, doing so often requires robust sample sizes that are spread across the full age range of the stock68,69. Size-selectivity in which smaller individuals are less vulnerable to capture can result in the underestimation of the theoretical age at which length is equal to zero (t0) and the Brody growth coefficient (k), which is related to stock productivity69. The age and length data presented here clearly show a gear bias as no fish smaller than 195 mm or younger than 8 y were captured. Fitting a traditional von Bertalanffy growth function would have resulted in biased parameter estimates, appearing to show slower growth, thus even lower productivity than estimated here69. The use of the Bayesian model that incorporated a size-at-birth prior to fitting the VBGM to validated age estimates produced a realistic fit to the data without having to fix parameter estimates.

The Brody growth coefficient in the blackbelly rosefish VBGM was estimated at 0.08 y−1, which is comparable to the slow growing, deep-water orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus) in the southwest Pacific70,71 and the sebastine thornyheads (Sebastolobus altivelis and S. alascanus) in the northwest Pacific72. The orange roughy fisheries in New Zealand and Australia are notorious for their collapse in the 1970s and 1980s due to age misspecification and resultant overexploitation11,73. The similarity in growth rates between blackbelly rosefish and orange roughy may suggest blackbelly rosefish stocks are similarly vulnerable to overexploitation1, thus also indicates conservative management approaches are warranted.

Deepwater marine fishes are often difficult to age and many are long-lived27,74. There have been attempts to validate age estimates of deepwater fishes via radiometric methods74,75, as well as application of the bomb 14C chronometer, using otolith-derived birth year material39,76,77. However, these attempts have often served to increase rather than decrease ageing uncertainty. Radiometric age estimates tend to have high levels of uncertainty, with the thornyhead rockfishes (Sebastolobus alascanus and S. altivelis) in the northwest Pacific having mean radiochemical age uncertainty of ± 7.9 y, based on analytical uncertainty1,72. Notably, this uncertainty increases with age, with a mean radiochemical age uncertainty of ± 16.4 y for samples estimated to be older than 40 y. Therefore, while radiometric methods can provide evidence of extreme longevity in long-lived fishes, measurement error means actual age estimates are highly uncertain.

Application of the bomb 14C chronometer to otolith (birth year) Δ14C signatures also has been similarly uninformative for age validation of long-lived, deepwater marine fishes, albeit for other reasons than radiometric ageing. This uncertainty is due to the fact that otolith cores are often substantially depleted in 14C relative to reference series that index Δ14CDIC in the well-mixed surface layer39,76,77,78. This trend has also been observed in long-lived sebastines in the north Pacific Ocean, Gulf of Alaska, and Bering Sea41,79, as well as other Helicolenus spp. in the western Pacific40. The offset between surface reference and otolith core Δ14C for species living at depths > 500 m is often reported to be 100–150‰, which is in the same range as the offset between nGOM blackbelly rosefish otolith core Δ14C and reference series Δ14C values. However, data reported here, as well as for the suite of nGOM deepwater fishes48, suggests deriving birth year Δ14C signatures from eye lens rather than otolith cores may enable the bomb 14C chronometer to be generally effective for age validation of deepwater fishes. It is currently unclear, however, if this approach has some depth threshold to its effectiveness, but to date it has been successfully applied to upper slope reef fishes that live at depths as great as 500 m. Given vertical migrants routinely (daily) transit from depths of 1,000 m or more into the epipelagic to forage80,81,82, it may be that the organic carbon available at those depths also has a contemporary surface bomb 14C signature. However, further testing, and perhaps coupling eye lens Δ14C signatures with either radiometric ageing or amino acid racemization83 approaches, could resolve this question.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are provided within the published article or will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Clark, M. Are deepwater fisheries sustainable? The example of orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus) in New Zealand. Fish. Res. 51, 123–135 (2001).

Morato, T., Cheung, W. W. L. & Pitcher, T. J. Vulnerability of seamount fish to fishing: Fuzzy analysis of life-history attributes. J. Fish Biol. 68, 209–221 (2006).

Rigby, C. & Simpfendorfer, C. A. Patterns in life history traits of deep-water chondrichthyans. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr., 115, 30–40 (2015).

Koslow, J. A, Boehlert, G. W., Gordon, J. D. M., Haedrich, R. L., Lorance, P. et al. Continental slope and deep-sea fisheries: implications for a fragile ecosystem. ICES J. Mar. Sci., 57, 548–557 (2000).

Roberts, C. M. Deep impact: The rising toll of fishing in the deep sea. Trends Ecol. Evol. 17, 242–245 (2002).

Norse, E. A. et al. Sustainability of deep-sea fisheries. Mar. Policy 36, 307–320 (2012).

Edwards, C. T. T., Hillary, R. M., Levontin, P., Blanchard, J. L. & Lorenzen, K. Fisheries assessment and management: A synthesis of common approaches with special reference to deepwater and data-poor stocks. Rev. Fish. Sci. 20, 136–153 (2012).

Francis, R. I. C. C. & Smith, D. C. Mean length, age, and otolith weight as potential indicators of biomass depletion for orange roughy, Hoplostethus atlanticus. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 29, 581–587 (1995).

Beamish, R. J. & McFarlane, G. A. The forgotten requirement for age validation in fisheries biology. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 112, 735–743 (1983).

Reeves, S. A simulation study of the implications of age-reading errors for stock assessment and management advice. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 60, 314–328 (2003).

Campana, S. Accuracy, precision and quality control in age determination, including a review of the use and abuse of age validation methods. J. Fish Biol. 59, 197–242 (2001).

Zhou, S., Yin, S., Thorson, J. T., Smith, A. D. M. & Fuller, M. Linking fishing mortality reference points to life history traits: an empirical study. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. 69, 1292–1301 (2012).

Then, A. Y., Hoenig, J. M., Hall, N. G. & Hewitt, D. A. Evaluating the predictive performance of empirical estimators of natural mortality rate using information on over 200 fish species. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 72, 82–92 (2015).

Lin Lai, H. & Gunderson, D. R. Effects of ageing errors on estimates of growth, mortality and yield per recruit for walleye pollock (Theragra chalcogramma). Fish. Res., 5, 287–302 (1987).

Rivard, D. & Foy, M. G. An analysis of errors in catch projections for Canadian Atlantic fish stocks. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. 44, 967–981 (1987).

Tyler, A. V., Beamish, R. J. & McFarlane, G. A. Implications of age determination errors to yield estimates in Effects of Ocean Variability on Recruitment and an Evaluation of Parameters used in Stock Assessment Models (ed. R. J. Beamish and G. A. McFarlane) 27–35 (Canadian Special Publication of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 1989).

Bradford, M. J. Effects of ageing errors on recruitment time series estimated from sequential population analysis. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. 48, 555–558 (1991).

Hüssy, K. & Mosegaard, H. Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) growth and otolith accretion characteristics modelled in a bioenergetics context. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. 61, 1021–1031 (2004).

Hanselman, D. A., Clark, W. G., Heifetz, J. & Anderl, D. M. Statistical distribution of age readings of known-age sablefish (Anoplopoma fimbria). Fish. Res. 131–133, 1–8 (2012).

Wakefield, C. B. et al. Ageing bias and precision for deep-water snappers: evaluating nascent otolith preparation methods using novel multivariate comparisons among readers and growth parameter estimates. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 74, 193–203 (2017).

Froese, R. & Pauly, D. (Eds). FishBase. World Wide Web Electronic Publication. www.fishbase.org. (2022).

White, D. B., Wyanski, D. M. & Sedberry, G. R. Age, growth, and reproductive biology of the blackbelly rosefish from the Carolinas, USA. J. Fish Biol., 53, 1274–1291 (1998).

Santos, R. V. S., Silva, W. M. M. L., Novoa-Pabon, A. M., Silva, H. M. & Pinho, M. R. Long-term changes in the diversity, abundance and size composition of deep sea demersal teleosts from the Azores assessed through surveys and commercial landings. Aquat. Living Resour. 32, 1–20 (2019).

Perotta, R. G. & Hernández, D. R. Stock assessment of the bluemouth (Helicolenus dactylopterus) in Azorean waters during the 1990–2002 period, applying a biomass dynamic model. Rev. Investig. Desarro. Pesq. 17, 81–93 (2005).

Ragonese, S. & Reale, B. Distribuzione e crescita dello scorfano di fondale, Helicolenus dactylopterus dactylopterus (Delaroche, 1809), nello stretto di Sicilia (Mar Mediterraneo). Biol. Mar. Mediterr. 2, 269–273 (1995).

Kelly, C. J., Connolly, P. L. & Bracken, J. J. Age estimation, growth, maturity, and distribution of the bluemouth rockfish Helicolenus d. dactylopterus (Delaroche 1809) from the Rockall Trough. ICES J. Mar. Sci., 56, 61–74 (1999).

Munk, K. M. Maximum ages of groundfishes in waters off Alaska and British Columbia and considerations of age determination. Alsk. Fish. Res. Bull. 8, 12–21 (2001).

Baker, M. S. Jr. & Wilson, C. A. Use of bomb radiocarbon to validate otolith section ages of red snapper Lutjanus campechanus from the northern Gulf of Mexico. Limnol. Oceanogr. 46, 1819–1824 (2001).

Fischer, A., Baker, M. Jr., Wilson, C. & Neiland, D. Age, growth, mortality, and radiometric age validation of gray snapper (Lutjanus griseus) from Louisiana. Fish. Bull. 103, 307–319 (2005).

Barnett, B. K., Thornton, L., Allman, R., Chanton, J. P. & Patterson, W. F. III. Linear decline in red snapper (Lutjanus campechanus) otolith Δ14C extends the utility of the bomb radiocarbon chronometer for fish age validation in the Northern Gulf of Mexico. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 75, 1664–1671 (2018).

Barnett, B. K., Chanton, J. P., Ahrens, R., Thornton, L. & Patterson, W. F. III. Life history of northern Gulf of Mexico Warsaw grouper Hyporthodus nigritus inferred from otolith radiocarbon analysis. PLoS ONE 15, e0228254 (2020).

Nydal, R. & Lövseth, K. Tracing bomb 14C in the atmosphere 1962–1980. J. Geophys. Res. 88, 3621–3642 (1983).

Kalish, J. M. Pre- and post-bomb radiocarbon in fish otoliths. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 114, 549–554 (1993).

Stuiver, M. & Polach, H. A. Discussion: Reporting of 14C data. Radiocarbon 19, 355–363 (1977).

Grottoli, A. G. & Eakin, C. M. A review of modern coral δ18O and Δ14C proxy records. Earth Sci. Rev. 81, 67–91 (2007).

Kastelle, C. R., Kimura, D. K. & Goetz, B. J. Bomb radiocarbon age validation of Pacific ocean perch (Sebastes alutus) using new statistical methods. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. 65, 1101–1112 (2008).

Kalish, J. M., Johnston, J. M., Smith, D. C., Morison, A. K. & Robertson, S. G. Use of the bomb radiocarbon chronometer for age validation in the blue grenadier Macruronus novaezelandiae. Mar. Biol. 128, 557–563 (1997).

Chung, M. T., Trueman, C. N., Godiksen, J. A. & Grønkjær, P. Otolith δ13C values as a metabolic proxy: approaches and mechanical underpinnings. Mar. Freshw. Res. 70, 1747–1756 (2019).

Cook, M., Fitzhugh, G. R. & Franks, J. S. Validation of yellowedge grouper, Epinephelus flavolimbatus, age using nuclear bomb-produced radiocarbon. Environ. Biol. Fishes 86, 461–472 (2009).

Grammer, G. L., Fallon, S. J., Izzo, C., Wood, R. & Gillanders, B. M. Investigating bomb radiocarbon transport in the southern Pacific Ocean with otolith radiocarbon. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 424, 59–68 (2015).

Kastelle, C. et al. Age validation of four rockfishes (genera Sebastes and Sebastolobus) with bomb-produced radiocarbon. Mar. Freshw. Res. 71, 1355–1366 (2020).

McNichol, A. P. et al. Ten years after—The WOCE AMS radiocarbon program. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 172, 479–484 (2000).

Guilderson, T. P., Roark, E. B., Quay, P. D., Flood Page, S. R. & Moy, C. Seawater radiocarbon evolution in the Gulf of Alaska: 2002 observations. Radiocarbon, 48, 1–15 (2006).

Patterson, W. F. III., Barnett, B. K., TinHan, T. C. & Lowerre-Barbieri, S. K. Eye lens Δ14C validates otolith-derived age estimates of Gulf of Mexico reef fishes. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. 78, 13–17 (2021).

Broecker, W. S. & Peng, T.-H. Tracers in the Sea (Lamont Doherty Geological Observatory, 1982).

Dahm, R., Schonthaler, H. B., Soehn, A. S., van Marle, J. & Vrensen, G. F. J. M. Development and adult morphology of the eye lens in the zebrafish. Exp. Eye Res. 85, 74–89 (2007).

Tzadik, O. E. et al. Chemical archives in fishes beyond otoliths: a review on the use of other body parts as chronological recorders of microchemical constituents for expanding interpretations of environmental, ecological, and life-history changes: chemical archives in fishes beyond otoliths. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 15, 238–263 (2017).

Patterson, W. F. III. & Chamberlin, D. W. Novel application of the bomb radiocarbon chronometer for age validation in deepwater reef fishes. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfas-2023-0003 (2023).

Beamish, R. J. & Fournier, D. A. A method for comparing the precision of a set of age determinations. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. 38, 982–983 (1981).

Campana, S. E., Annand, M. C. & Mcmillan, A. I. Graphical and statistical methods for determining the consistency of age determinations. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 124, 131–138 (1995).

Druffel, E. M. Radiocarbon in annual coral rings of the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. University of California, San Diego. 213 pp (1980).

Druffel, E. R. M. Decade time scale variability of ventilation in the North Atlantic: High-precision measurements of bomb radiocarbon in banded corals. J. Geophys. Res. 94, 3271–3285 (1989).

Wagner, A. J. Oxygen and carbon isotopes and coral growth in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea as environmental and climate indicators. Texas A&M University. 117 pp (2009).

Moyer, R. P. & Grottoli, A. G. Coral skeletal carbon isotopes (δ13C and Δ14C) record the delivery of terrestrial carbon to the coastal waters of Puerto Rico. Coral Reefs 30, 791–802 (2011).

Toggweiler, J. R., Druffel, E. R. M., Key, R. M. & Galbraith, E. D. Upwelling in the ocean basins north of the ACC: 1. On the upwelling exposed by the surface distribution of Δ14C. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans, 124, 2591–2608 (2019).

Chamberlin, D. W., Siders, Z. A., Barnett, B. K., Ahrens, R. N. M. & Patterson III, W. F. Highly variable length-at-age in vermilion snapper (Rhomboplites aurorubens) validated via Bayesian analysis of bomb radiocarbon. Fish. Res., 264, 106732 (2023).

Gabry, J. & Češnovar, R. cmdstanr: R interface to “CmdStan.” https://mc-stan.org/cmdstanr/, https://discourse.mc-stan.org (2022).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/ (2020).

Gelman, A. & Rubin, D. B. Inference from iterative simulation using multiple sequences. Stat. Sci. 7, 457–511 (1992).

von Bertalanffy, L. Untersuchungen Über die Gesetzlichkeit des Wachstums : I. Teil: Allgemeine Grundlagen der Theorie; Mathematische und physiologische Gesetzlichkeiten des Wachstums bei Wassertieren. Wilhelm Roux’ Archiv fur Entwicklungsmechanik der Organismen, 131, 613–652 (1934).

Cailliet, G. M., Smith, W. D., Mollet, H. F. & Goldman, K. J. Age and growth studies of chondrichthyan fishes: the need for consistency in terminology, verification, validation, and growth function fitting. Environ. Biol. Fishes 77, 211–228 (2006).

Caltabellotta, F. P., Siders, Z. A., Cailliet, G. M., Motta, F. S. & Gadig, O. B. F. Preliminary age and growth of the deep-water goblin shark Mitsukurina owstoni (Jordan, 1898). Mar. Freshw. Res. 72, 432–438 (2021).

Stan Development Team. RStan: The R interface to Stan. https://mc-stan.org/ (2022).

Moser, H. G., Ahlstrom, E. H. & Sandknop, E. M. Guide to the identification of scorpionfish larvae (family Scorpaenidae) in the eastern Pacific with comparative notes on species of Sebastes and Helicolenus from other oceans. NOAA Technical Report NMFS Circular 402 (1977).

Hamel, O. S. & Cope, J. M. Development and considerations for application of a longevity-based prior for the natural mortality rate. Fish. Res. 256, 1–8 (2022).

Ribas, D., Muñoz, M., Casadevall, M. & Gil de Sola, L. How does the northern Mediterranean population of Helicolenus dactylopterus dactylopterus resist fishing pressure? Fish. Res., 79, 285–293 (2006).

Stawitz, C. C., Haltuch, M. A. & Johnson, K. F. How does growth misspecification affect management advice derived from an integrated fisheries stock assessment model?. Fish. Res. 213, 12–21 (2019).

Taylor, N. G., Walters, C. J. & Martell, S. J. D. A new likelihood for simultaneously estimating von Bertalanffy growth parameters, gear selectivity, and natural and fishing mortality. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. 62, 215–223 (2005).

Gwinn, D. C., Allen, M. S. & Rogers, M. W. Evaluation of procedures to reduce bias in fish growth parameter estimates resulting from size-selective sampling. Fish. Res. 105, 75–79 (2010).

Mace, P. M., Fenaughty, J. M., Coburn, R. P. & Doonan, I. J. Growth and productivity of orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus) on the north Chatham Rise. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 24, 105–119 (1990).

Smith, D. C., Robertson, S. G., Fenton, G. E. & Short, S. A. Age determination and growth of orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus): a comparison of annulus counts with radiometric ageing. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. 52, 391–401 (1995).

Kline, D. E. Radiochemical age verification for two deep-sea rockfishes, Sebastolobus altivelis and S. alascanus. San Jose State University, San Jose, CA. 141 pp (1996).

Clark, M. Experience with management of orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus) in New Zealand waters, and the effects of commercial fishing on stocks over the period 1980–1993 in Deepwater Fisheries of the North Atlantic Oceanic Slope (ed. Hopper, A.G.) 251–266 (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1995).

Cailliet, G. M. et al. Age determination and validation studies of marine fishes: do deep-dwellers live longer?. Exp. Gerontol. 36, 739–764 (2001).

Andrews, A. H. et al. Bomb radiocarbon and lead—Radium disequilibria in otoliths of bocaccio rockfish (Sebastes paucispinis): a determination of age and longevity for a difficult-to-age fish. Mar. Freshw. Res. 56, 517–525 (2005).

Filer, K. R. & Sedberry, G. R. Age, growth and reproduction of the barrelfish Hyperoglyphe perciformis (Mitchill) in the western North Atlantic. J. Fish Biol. 72, 861–882 (2008).

Lombardi-Carlson, L. A. & Andrews, A. H. Age estimation and lead-radium dating of golden tilefish, Lopholatilus chamaeleonticeps. Environ. Biol. Fishes 98, 1787–1801 (2015).

McMillan, P. J. et al. Review of life history parameters and preliminary age estimates of some New Zealand deep-sea fishes. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 55, 565–591 (2021).

Kerr, L. A. et al. Radiocarbon in otoliths of yelloweye rockfish (Sebastes ruberrimus): a reference time series for the coastal waters of southeast Alaska. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. 61, 443–451 (2004).

Hernández-León, S. et al. Carbon sequestration and zooplankton lunar cycles: Could we be missing a major component of the biological pump?. Limnol. Oceanogr. 55, 2503–2512 (2010).

Hernández-León, S., Calles, S. & de Puelles, M. L. The estimation of metabolism in the mesopelagic zone: Disentangling deep-sea zooplankton respiration. Prog. Oceanogr., 178, 1–8 (2019).

Cavan, E. L., Henson, S. A., Belcher, A. & Sanders, R. Role of zooplankton in determining the efficiency of the biological carbon pump. Biogeosciences 14, 177–186 (2017).

Chamberlin, D. W., Shervette, V. R., Kaufman, D. S., Bright, J. E. & Patterson, W. F. III. Can amino acid racemization be utilized for fish age validation?. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. 80, 642–647 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the many researchers, TIP port samplers, and fishers who were integral in collecting and processing the data presented in this manuscript. In particular, we would like to acknowledge Captain Johnny Green and the crew of the F/V Intimidator for aiding in collecting samples. We thank Miaya Glabach for help in sample processing and Bill Kline for assistance with micromilling. We are also grateful for the support and expertise provided by Kathy Elder, Susan Handwork, and others at NOSAMS for otolith and eye lens Δ14C analysis. Funding for this research was provided by the NOAA Fisheries Cooperative Research Program grant #NA18NMF4540080 and NOAA Fisheries Marine Fisheries Initiative grant #NA21NMF4330501. The scientific results and conclusions, as well as any views or opinions expressed herein, are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of NOAA or the Department of Commerce.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.C. and W.P. conceived of and designed this study. They oversaw the collection of samples and conducted the ageing presented here. D.C processed the 14C samples that were analyzed at NOSAMS. Z.S. designed and coded the Bayesian spline model used to determine ageing accuracy and the Bayesian VBGM used to estimate growth parameters. B.B. provided the archived samples from NOAA Fisheries and input on otolith coring. The manuscript first draft was written by D.C. and revised with input from all co-authors. All authors have reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chamberlin, D.W., Siders, Z.A., Barnett, B.K. et al. Eye lens-derived Δ14C signatures validate extreme longevity in the deepwater scorpaenid blackbelly rosefish (Helicolenus dactylopterus). Sci Rep 13, 7438 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34680-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34680-0

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.