Abstract

Polymers are often combined with magnetostrictive materials to enhance their toughness. This study reports a cellulose nanofibril (CNF)-based composite paper containing dispersed CoFe2O4 particles (CNF–CoFe2O4). Besides imparting magnetization and magnetostriction, the incorporation of CoFe2O4 particles decreased the ultimate tensile strength and increased the fracture elongation of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper. CNF was responsible for the tensile properties of CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper. Consequently, the magnetic and magnetostrictive properties and tensile properties of CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper can be controlled by changing the mixture ratio of CNF and CoFe2O4 particles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To alleviate the global energy crisis and environmental pollution, many researchers are exploring alternative energy technologies that harvest energy from the ambient environment (e.g., mechanical vibrations)1,2,3. When the ambient energy supply is limited, piezoelectric-energy harvesting devices generate sufficient power for targeted devices such as Internet of Things sensors4. For this purpose, piezoelectric materials, composites, and devices have been actively researched5,6,7,8,9,10,11 and their vibration-energy harvesting performances have been evaluated.

Magnetostrictive materials can deform under an external magnetic field12. The magnetostrictive effect was first described by James Prescott Joule in 184213. He reported that iron, a ferromagnetic material, changes its dimension in response to a magnetic field. Since that time, researchers have developed various magnetostrictive materials such as Tb–Dy–Fe alloys (terfenol-D), Fe–Ga alloys (galfenol), Fe–Co alloys, and CoFe2O4 (cobalt ferrites)14,15,16,17,18. Magnetostrictive materials, composites, and devices are also attracting attention in the energy harvesting field19,20,21,22,23,24. Terfenol-D and galfenol are well-known giant magnetostrictive alloys showing good magnetostrictive properties at room temperature, but are brittle and expensive1,16.

To overcome the brittleness of magnetostrictive materials, many researchers have dispersed magnetostrictive particles through a polymer matrix, forming magnetostrictive polymer composites (MPCs)25. Under an external magnetic field, the magnetostrictive particles deform and exert a force on the polymer matrix, deforming the whole composite. Equilibrium is achieved by balancing the stresses generated in the magnetostrictive particles and the polymer matrix, resulting in overall deformation of the MPC. MPCs are potentially applicable to current and stress sensing, vibration damping, actuation, health monitoring, and biomedical applications. In addition, they are easier to manufacture to the required geometry than the above-mentioned giant magnetostrictive alloys. Previous studies on MPCs have reported terfenol-D particles26 and galfenol particles27 dispersed through an epoxy resin matrix (terfenol-D/epoxy and galfenol/epoxy composites, respectively), Fe–Co alloy particles dispersed through a polyurethane matrix (Fe–Co/PU composites)28 and various others29,30. Positive magnetostriction values of 1600, 360, and 70 ppm have been reported in terfenol-D/epoxy, galfenol/epoxy, and Fe–Co/PU, respectively. However, MPCs with negative magnetostrictive effect have only been investigated to a small degree. Nersessian et al.31 reported saturation magnetostrictions of − 24 and − 28 ppm in hollow and solid nickel composites, respectively. Similarly, Ren et al.32 reported negative magnetostriction in polymer-bonded Sm0.88Dy0.12Fe1.93 pseudo-1-3 composites.

Recently, paper- and cellulose-based devices have gained increasing attention33 because paper is low cost (~ 0.005 $/m2), biocompatible, environmentally friendly, 100% recyclable, and more stretchable than other polymer-based flexible devices34. Cellulose fiber is inexpensive, bio-based, biodegradable, non-hazardous, recyclable, and low-density35. Cellulose nanofibrils (CNFs) in particular show outstanding strength, stiffness, and toughness36 and are expected to be utilized as reinforcing fibers37,38,39,40,41,42,43.

Mattos et al.44 showed that nanonetworks created from CNFs can form superstructures with virtually any kind of particle because of supramolecular cohesion provided by the fibrils. This cohesion was shown to be a result of the high aspect ratio of the fibrils. Yermakov et al.45 fabricated magnetostrictive nanocellulose membranes by embedding terfenol-D particles into CNFs. After evaluating the magnetostrictive properties of the membranes, they found that various orientations of the terfenol-D particles were induced in the membranes, and that particles with in-plane alignment showed the strongest magnetostrictive effect. Kim et al.46 fabricated a magnetostrictive actuator string which could respond to an external magnetic field, by combining magnetic nanoparticles of Fe2O3 in a CNF matrix. However, there are no publications where magnetostrictive composites were made by combining CNFs and CoFe2O4. Antonel et al.47 produced a CoFe2O4-poly(aniline) composite by embedding CoFe2O4 nanoparticles inside a poly(aniline) polymer matrix. They showed that due to particle-polymer interactions, by varying the particle-polymer ratio one can modulate the magnetic behavior of the material.

In the present study, CoFe2O4 particles were dispersed through CNF to form CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers. This paper reports the magnetic, magnetostrictive, and tensile properties of the papers. The microstructures of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers were observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) and an X-ray diffraction (XRD) system.

Experimental procedure

Specimen preparation

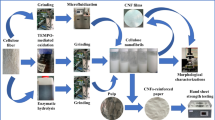

Figure 1 is a schematic of the fabrication process of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers. The starting materials were CoFe2O4 particles (Kojundo Chemical Laboratory Co., Ltd., Japan) and a 2 wt% CNF slurry (IMA-10002, Sugino Machine, Japan). The CoFe2O4 particle size distribution was measured by a laser diffraction particle size analyzer (MASTERSIZER 3000, Malvern Panalytical, Spectris, UK). The CoFe2O4 particles and CNF slurry were manually mixed for 5 min at room temperature by hand-mixing. Using different weight ratios of CoFe2O4 particles: CNF slurry, 3 solutions were prepared: 5:95, 20:80 and 35:65, total weight 20 g. The solutions were sandwiched between two mesh sheets sized 100 \(\times \) 100 mm2. The samples were compressed and dehydrated under an ultra-compact manual hydraulic heating press (Model IMC-195A-E, Imoto Mfg. Co., Ltd., Japan) operated at 120 °C for 30 s. After peeling off the mesh sheets, the dehydrated CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers were further compressed and dried using a 2500 g weight for 24 h. The circular CoFe2O4 plate (\(\phi \) 15 \(\times \) 2.25 mm3) was then consolidated by spark plasma sintering (SPS, SPS-1050, Fuji Electric Industrial Co., Ltd., Japan), under a compressive stress of 20 MPa at 1000 °C for 10 min in a vacuum. A reference CoFe2O4 plate was cut to a size of 10 \(\times \) 10 \(\times \) 2.25 mm3 and reserved for further measurements.

Density

To obtain the densities of the CoFe2O4 composite papers and CoFe2O4 sintered plate, the lengths and thicknesses of the samples were measured using an electronic digital caliper (SDV-150, Fujiwara Industrial Co., Ltd., Japan) and a digital thickness gauge (MDC-SX, Mitutoyo, Japan), respectively, and the weights of the samples were measured on a digital scale (ALE223R, Sinko Denshi Co., Ltd., Japan).

Microstructure analysis

The microstructures of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers and CoFe2O4 particles were investigated in a multipurpose XRD system (Ultima IV, Rigaku Co., Japan). The XRD patterns were obtained under CuK\({\upalpha }\) radiation with a counting time of 1.67/s, a step size of 0.02°, a voltage of 40 kV, and a current of 40 mA. The scanning range was determined to be between 10° and 70°. The microstructures of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers were observed using a field emission SEM (FE-SEM) (SU-70, Hitachi High-Tech Co., Ltd., Japan), with an acceleration voltage of 5 kV and a working distance of 10 mm. In preparation for FE-SEM, the surfaces of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers were sputtered for 30 s using an ion sputtering device (E-1045, Hitachi High-Tech Co., Ltd., Japan) with a discharge current of 15 mA at 15 Pa to provide electrical conductivity to the composite papers. Furthermore, the FE-SEM was equipped with an energy dispersed X-ray spectrometer (EDX) for measuring the carbon (C), oxygen (O), cobalt (Co) and iron (Fe) concentrations in the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers. The EDX was operated at an acceleration voltage of 5 kV and a working distance of 15 mm.

Magnetic and magnetostrictive properties

The magnetic properties of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers were evaluated using a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) (BHV-50H, Riken Denshi Co., Ltd., Japan) calibrated to 4.931 emu. The VSM was calibrated on a pure nickel plate sized 10 \(\times \) 10 \(\times \) 0.1 mm3. The applied magnetic field range was ± 759 kA/m. The magnetostrictive properties of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers were evaluated under the VSM electromagnets. The electromagnets were separated by 50 mm. The applied magnetic field was measured with a gauss meter (GM-4002, Denshijiki Industry Co., Ltd., Japan). The strains of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers were measured by an orthogonal strain gauge (JFGS-1-120-D16-16 L3M2S, Kyowa Electronic Instruments Co., Ltd., Japan) positioned on the sample surface under an applied magnetic field range of ± 733 kA/m. The data were collected by data loggers (NR-ST04 and NR-HA08, Keyence, Japan)28.

Tensile properties

The tensile properties of CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper specimens sized 30 \(\times \) 15 mm2 were investigated on a compact tabletop tester (EZ-SX, Shimazu Co., Ltd., Japan) with a 500-N load cell (Shimazu Co., Ltd., Japan). The tensile grips were separated by 15 mm. #600-grit sandpaper was inserted between the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper and the tensile grips to prevent slipping.

Theory

This section formulates the problem of predicting the effective magneto-mechanical properties of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper. In rectangular Cartesian coordinates xi (O-x1, x2, x3), the constitutive equations of the heterogeneous magnetostrictive composite material are given by Eqs. (1) and (2)

where \(\langle{\varepsilon }_{ij}\rangle,\langle{\sigma }_{kl}\rangle,\langle{B}_{i}\rangle\) and \(\langle{H}_{k}\rangle\) are the average components of the strain tensor, stress tensor, magnetic flux density vector, and magnetic field intensity vector, respectively, and \({s}_{ijkl}^{*\mathrm{H}}\), \({d}_{kij}^{*}\) and \({\mu }_{ik}^{*\mathrm{T}}\) are the elastic compliance under a constant magnetic field, the piezomagnetic constant, and the magnetic permittivity under a constant stress, respectively. Hereafter, the asterisk (*) will denote the effective average properties of the magnetostrictive composite material. This formulation adopts the compressed matrix notation, which is more useful than the extended tensor notation when discussing symmetry. In this matrix notation, ij or kl (i, j, k, l = 1, 2, 3) is replaced with p, q (valued from 1 to 6). Equations (1) and (2) are then rewritten as Eqs. (3) and (4)

To demonstrate the effective properties of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers, we consider the longitudinal magnetostrictive effect, meaning that the external field (either mechanical stress or a magnetic field) acts along the x3-direction (the easy magnetization axis of the composite paper). The magneto-mechanical coupling factor is given by Eq. (5)

where \({E}^{*}\) is the Young’s modulus (slope of the stress–strain plot) of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper. Note that the material properties \({E}^{*}\), \({d}_{33}^{*}\) and \({\mu }_{33}^{*\mathrm{T}}\) are functions of the volume fractions of the CoFe2O4 particles (\({V}_{\mathrm{cfo}}\)), \(\mathrm{the}\) pores (\({V}_{\mathrm{p}}\)), and of the CNF matrix \(({V}_{\mathrm{m}} = 1-({V}_{\mathrm{cfo}}+{V}_{\mathrm{p}}))\), respectively. Thus the material properties are calculated by inserting the volume fractions into Eqs. (6)–(8):

where \(\mathrm{the}\) subscripts cfo, p, and m represent the CoFe2O4 particles, pores, and matrix (i.e., CNF), respectively.

Results and discussion

The weight fractions of CoFe2O4 (\({W}_{\mathrm{cfo}}\)) and CNF (\({W}_{\mathrm{m}}\)) in the composite papers are displayed in Table 1. The real densities of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers were 0.7983 g/cm3 (sample from 5:95 solution), 1.1967 g/cm3 (sample from 20:80 solution), and 1.5058 g/cm3 (sample from 35:65 solution). Assuming that all water was evaporated from the dried CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper and taking the theoretical densities of CoFe2O4 and cellulose (5.2948 and 1.50 g/cm3, respectively), the volume fractions of CoFe2O4 particles in samples made from the 5:95, 20:80, and 35:65 solutions were calculated as 10.9, 21.0, and 27.5 vol%, respectively, in the final CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers (see Table 1). The average thicknesses of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers containing 10.9, 21.0, and 27.5 vol% CoFe2O4 were 0.25, 0.49, and 0.92 mm, respectively. The real density of the CoFe2O4 sintered plate was 4.298 g/cm3. The relative density of the CoFe2O4 sintered plate was calculated as 81.2% of the theoretical density of 5.29 g/cm3.

Figure 2 shows the size distributions of the CoFe2O4 particles. The CoFe2O4 powder comprised small and large particle populations with approximate diameters of 10 and 150 μm, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3, the XRD patterns of the 10.9 vol% CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper matched those of the CoFe2O4 particles. Therefore, the CoFe2O4 was stable against chemical transformations during the fabrication process. Figure 4 shows the SEM images of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers. Although the CoFe2O4 particles were dispersed through the CNF matrix, they were agglomerated by the hand mixing process. The size distribution peak at 150 μm in Fig. 2 was probably contributed by large agglomerates of CoFe2O4 particles. Figure 5 shows the EDX mapping of the 27.5 vol% CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper (the micrograph is shown in Fig. 4c). The EDX detected C, O, Co, and Fe on the surface of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers, implying that CoFe2O4 was stable against chemical reactions during the fabrication process, reconfirming the XRD results. It should be noted that no characteristic intensities of the X-ray appeared in the shadow of the EDX detector because they were attenuated by the uneven surface of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper surface.

Figure 6 shows the magnetic properties of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers and CoFe2O4 plate. The CoFe2O4 additives magnetized the CNF paper. The maximum magnetization of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper linearly increased with increasing proportion of CoFe2O4 particles. Consistent with the present results, Williams et al.49 reported that the magnetic properties of magnetizing cellulose fibers depend on the volume percentage of the implemented magnetic filler in the fiber network. The magnetic curve of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper reached saturation more slowly than the CoFe2O4 sintered plate. In Eq. (4), the effective magnetic permittivity \({\mu }_{33}^{*\mathrm{T}}\) of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper under stress-free conditions was given by Eq. (9)

The apparent effective magnetic permittivities \({\mu }_{33}^{*\mathrm{T}}\) of CNF–CoFe2O4 with CoFe2O4 contents of 10.9, 21.0, and 27.5 vol% were evaluated as 0.0769 \(\times \) 10−6, 0.127 \(\times \) 10−6, and 0.228 \(\times \) 10−6 H/m, from the initial slope in Fig. 6a (see Table 1).

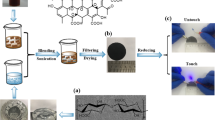

Figure 7 shows the magnetostrictive properties of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers and CoFe2O4 plate. In the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper, the magnetostriction was negative and positive in the directions parallel and perpendicular to the magnetic field, respectively, as expected. The magnetostriction of CoFe2O4 plate first increased to a maximum negative value and then decreased. The maximum negative value of the CoFe2O4 plate was − 90 ppm under a magnetic field of 217 kA/m. Bozorth et al.50 said that CoFe2O4 has two magnetostriction coefficients \({\lambda }_{100}\) and \({\lambda }_{111}\): \({\lambda }_{100}<0\) and \({\lambda }_{111}>0\) at 300 K. Since the easy magnetization axis of CoFe2O4 is [100], correspondingly, it has a large negative \({\lambda }_{100}\) and a small positive \({\lambda }_{111}\)51,52. It is believed that the same phenomenon occurred. The maximum negative magnetostriction of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper deviated from the fitting line (see Fig. 7e). It should be noted that the 10.9 and 21.0 vol% CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers failed to achieve magnetostrictive saturation under a magnetic field of \({H}_{3}=\pm \) 733 kA/m. These results imply that the CNFs between the CoFe2O4 particles deformed with magnetostriction of the CoFe2O4 particles and facilitated linear magnetostriction of the whole CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper. In Eq. (3), the effective piezomagnetic constant \({d}_{33}^{*}\) of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper under stress-free conditions was calculated as Eq. (10).

After straight-line fitting of the linear portions of the curves in Fig. 7a–c, the \({d}_{33}^{*}\) values of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers containing 10.9, 21.0, and 27.5 vol% CoFe2O4 were calculated as − 8.95 \(\times \) 10−12, − 66.5 \(\times \) 10−12, and − 166 \(\times \) 10−12 m/A, respectively (see Table 1). Clearly, the \({d}_{33}^{*}\) of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper increased with increasing CoFe2O4 particle addition. Using Eq. (3), the effective piezomagnetic constant \({d}_{31}^{*}\) of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper under stress-free conditions was obtained as Eq. (11).

Similarly, the \({d}_{31}^{*}\) values of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers containing 10.9, 21.0, and 27.5 vol% CoFe2O4 were calculated as 0.391 \(\times \) 10−12, 18.8 \(\times \) 10−12, and 27.1 \(\times \) 10−12 m/A, respectively.

Figure 8a shows the stress-elongation curves of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers. Here, the elongation was estimated from the displacement of the universal testing machine crosshead. The initial slopes (between 0 and 0.2% elongation) of the stress–elongation curves of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers were calculated for the 10.9, 21.0, and 27.5 vol% specimens, and they were determined as 0.523, 0.269, and 0.195 GPa, respectively (see Table 1). These values were taken as the apparent effective Young’s moduli. Figures 8 (b and c) plot the ultimate tensile strengths (UTSs) and fracture elongations versus CNF volume fraction in the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers. The CNF volume fractions in the 10.9, 21.0, and 27.5 vol% composite papers were 14.7, 5.9, and 3.6 vol%, respectively. The UTS of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper was increased by the addition of CNFs. However, the addition of CoFe2O4 particles decreased the UTS, i.e., CNF was responsible for the tensile properties of CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers. Therefore, the magnetic and magnetostrictive properties and tensile properties of CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers can be controlled by changing the mixture ratio of CNF and CoFe2O4 particles. The apparent \({k}_{33}^{2}\) values of the 10.9, 21.0, and 27.5 vol% CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper were 5.45 \(\times \) 10−16, 9.37 \(\times \) 10−15, and 2.36 \(\times \) 10−14, respectively (see Table 1). The improved magneto-mechanical coupling factor after adding CoFe2O4 implies that the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper is a promising candidate for energy harvesting applications.

Conclusion

This study evaluated the magnetic, magnetostrictive, and tensile properties of CNF–CoFe2O4 composite papers with different volume fractions of CoFe2O4. The XRD and EDX analyses revealed that CoFe2O4 remained stable during the fabrication process. The SEM images confirmed that CoFe2O4 particles were dispersed through the CNF matrix but were sometimes agglomerated. The CoFe2O4 particles imparted magnetization to the CNF paper and the maximum magnetization of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper was a linearly increasing function of CoFe2O4 content. The magnetostriction of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper was negative and positive in the directions parallel and perpendicular to the magnetic field, respectively. The apparent effective Young’s modulus and UTS of the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper decreased with increasing CoFe2O4. This was because increased amount of CoFe2O4 particles decreased the CNF volume fraction of the composite paper. Conclusively, the CNF was responsible for the tensile properties of CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper. Therefore, the magnetic and magnetostrictive properties and tensile properties of CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper can be controlled by changing the mixture ratio of CNF and CoFe2O4 particles. Overall, the CoFe2O4 additives impart magnetic and magnetostrictive properties to the CNF paper and may increase its toughness in exchange for decreasing its tensile properties. The magneto-mechanical coupling factor of the paper was improved by adding CoFe2O4 particles; therefore, the CNF–CoFe2O4 composite paper is expected to be available for energy harvesting applications.

Data availability

The materials described in the manuscript, including all relevant raw data, will be freely available to any researcher wishing to use them for non-commercial purposes from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Narita, F. & Fox, M. A Review on Piezoelectric, Magnetostrictive, and Magnetoelectric Materials and Device Technologies for Energy Harvesting Applications. Adv. Eng. Mater. 20, 1700743 (2018).

Surmenev, R. A. et al. Hybrid lead-free polymer-based nanocomposites with improved piezoelectric response for biomedical energy-harvesting applications: A review. Nano Energy 62, 475–506 (2019).

Sezer, N. & Koç, M. A comprehensive review on the state-of-the-art of piezoelectric energy harvesting. Nano Energy 80, 105567 (2021).

Song, H. C. et al. Piezoelectric energy harvesting design principles for materials and structures: Material figure-of-merit and self-resonance tuning. Adv. Mater. 32, 2002208 (2020).

Hara, Y., Zhou, M., Li, A., Otsuka, K. & Makihara, K. Piezoelectric energy enhancement strategy for active fuzzy harvester with time-varying and intermittent switching. Smart Mater. Struct. 30, 015038 (2021).

Wang, Z., Maruyama, K. & Narita, F. A novel manufacturing method and structural design of functionally graded piezoelectric composites for energy-harvesting. Mater. Des. 214, 110371 (2022).

Maruyama, K. et al. Electromechanical characterization and kinetic energy harvesting of piezoelectric nanocomposites reinforced with glass fibers. Compos. Sci. Technol. 223, 109408 (2022).

Sanchez, F. J. D. et al. Sponge-like piezoelectric micro- and nanofiber structures for mechanical energy harvesting. Nano Energy 98, 107286 (2022).

Mori, K., Narita, F., Wang, Z., Horibe, T. & Maejima, K. Thermoelectromechanical characteristics of piezoelectric composites under mechanical and thermal loading. Adv. Eng. Mater. 24, 2101212 (2022).

Vijayakanth, T., Liptrot, D. J., Gazit, E., Boomishankar, R. & Bowen, C. R. Recent advances in organic and organic–inorganic hybrid materials for piezoelectric mechanical energy harvesting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2109492 (2022).

Chen, B., Jia, Y., Narita, F., Wang, C. & Shi, Y. Multifunctional cellular sandwich structures with optimised core topologies for improved mechanical properties and energy harvesting performance. Compos. B Eng. 238, 109899 (2022).

Takacs, G. & Rohal-Ilkiv, B. Model Predictive Vibration Control: Efficient Constrained MPC Vibration Control for Lightly Damped Mechanical Structures (Springer, 2012).

Joule, J. P. On a new class of magnetic forces. Ann. Electr. Magn. Chem. 8, 219–224 (1842).

Grossinger, R. et al. Giant magnetostriction in rapidly quenched Fe-Ga. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 320, 2457–2465 (2008).

Wang, J., Gao, X., Yuan, C., Li, J. & Bao, X. Magnetostriction properties of oriented polycrystalline CoFe2O4. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 401, 662–666 (2016).

Guo, X. et al. Magnetic domain and magnetic properties of Tb–Dy–Fe alloys directionally solidified and heat treated in high magnetic fields. IEEE Trans. Magn. 57, 3013318 (2020).

Yamaura, S. Microstructure and magnetostriction of heavily groove-rolled Fe–Co alloy wires. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 264, 114946 (2021).

Gao, C., Zeng, Z., Peng, S. & Shuai, C. Magnetostrictive alloys: Promising materials for biomedical applications. Bioact. Mater. 8, 177–195 (2022).

Yang, Z. et al. Design, fabrication and evaluation of metal-matrix lightweight magnetostrictive fiber composites. Mater. Des. 175, 107803 (2019).

Yang, Z. et al. Evaluation of vibration energy harvesting using a magnetostrictive iron–cobalt/nickel-clad plate. Smart Mater. Struct. 28, 034001 (2019).

Clemente, C. S., Davino, D. & Loschiavo, V. P. Analysis of a magnetostrictive harvester with a fully coupled nonlinear FEM modeling. IEEE Trans. Magn. 57, 9355166 (2021).

Nakajima, K., Tanaka, S., Mori, K., Kurita, H. & Narita, F. Effects of heat treatment and Cr content on the microstructures, magnetostriction, and energy harvesting performance of Cr-doped Fe–Co alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 24, 2101036 (2022).

Li, A. et al. Energy harvesting using a magnetostrictive transducer based on switching control. Sens. Actuator A Phys. 355, 114303 (2023).

Kurita, H., Lohmuller, P., Laheurte, P., Nakajima, K. & Narita, F. Additive manufacturing and energy-harvesting performance of honeycomb-structured magnetostrictive Fe52–Co48 alloys. Addit. Manuf. 54, 102741 (2022).

Elhajjar, R., Law, C. T. & Pegoretti, A. Magnetostrictive polymer composites: Recent advances in materials, structures and properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 97, 204–229 (2018).

Altin, G. Static properties of crystallographically aligned terfenol-D/polymer composites. J. Appl. Phys. 101, 033537 (2007).

Walters, K., Busbridge, S. & Walters, S. Magnetic properties of epocy-bonded iron-gallium particulate composites. Smart Mater. Struct. 22, 025009 (2013).

Kurita, H., Keino, T., Senzaki, T. & Narita, F. Direct and inverse magnetostrictive properties of Fe–Co–V alloy particle-dispersed polyurethane matrix soft composite sheets. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 337, 113427 (2022).

Guan, X., Dong, X. & Ou, J. Magnetostrictive effect of magnetorheological elastomer. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 320(3–4), 153–163 (2008).

Diguet, G., Beaugnon, E. & Cavaillé, J. Y. Shape effect in the magnetostriction of ferromagnetic composite. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 322(21), 3337–3341 (2010).

Nersessian, N., Or, S. W., Carman, G. P., Choe, W. & Radousky, H. B. Hollow and solid spherical magnetostrictive particulate composites. J. Appl. Phys. 96, 3362 (2004).

Ren, W. J., Or, S. W., Chan, H. L. W. & Zhang, Z. D. Magnetoelastic properties of polymer-bonded Sm0.88Dy0.12Fe1.93 pseudo-1-3 composites. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 293, 908–912 (2005).

Shi, K. et al. Cellulose/BaTiO3 aerogel paper based flexible piezoelectric nanogenerators and the electric coupling with triboelectricity. Nano Energy 57, 450–458 (2019).

Thakur, A. & Devi, P. Paper-based flexible devices for energy harvesting, conversion and storage applications: A review. Nano Energy 94, 106927 (2022).

Ardanuy, M., Claramunt, J. & Filho, R. D. T. Cellulosic fiber reinforced cement-based composites: A review of recent research. Constr. Build. Mater. 79, 115–128 (2015).

Lam, W. S., Lee, P. F. & Lam, W. H. Cellulose nanofiber for sustainable production: A bibliometric analysis. Mater. Today Proc. 62, 6460 (2022).

Bhatnagar, A. & Sain, M. Processing of cellulose nanofiber-reinforced composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 24(12), 1229–1340 (2005).

Iwamoto, S., Kai, W., Isogai, A. & Iwata, T. Elastic modulus of single cellulose microfiber from tunicate measured by atomic force microscopy. Biomacromolecules 10(9), 2571–2576 (2009).

Mittal, N. et al. Multiscale control of nanocellulose assembly: Transferring remarlable nanoscale fibril mechanics to macroscale fibers. ACS Nano 12(7), 6378–6388 (2018).

Xie, Y., Kurita, H., Ishigami, R. & Narita, F. Assessing the flexural properties of epoxy composites with extremely low addition of cellulose nanofiber content. Appl. Sci. 10, 1159 (2020).

Kurita, H., Ishigami, R., Wu, C. & Narita, F. Mechanical properties of mechanically-defibrated cellulose nanofiber reinforced epoxy resin matrix composites. J. Compos. Mater. 55, 455–463 (2021).

Kurita, H., Bernard, C., Lavrovsky, A. & Narita, F. Tensile properties of mechanically-defibrated cellulose nanofiber-reinforced polylactic acid matrix composites fabricated by fused deposition modeling. Trans. Nanjing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 38, 68–74 (2021).

Wu, C. et al. Nanocellulose reinforced silkworm silk fibers for application to biodegradable polymers. Mater. Des. 202, 109537 (2021).

Mattos, B. D. et al. Nanofibrillar networks enable universal assembly of superstructured particle constructs. Sci. Adv. 6(19), 7328 (2020).

Yermakov, A. et al. Flexible magnetostrictive nanocellulose membranes for actuation, sensing, and energy harvesting applications. Front. Mater. 7, 2296–8016 (2020).

Kim, J. & Hyun, J. Soft magnetostrictive actuator string with cellulose nanofiber skin. ACS Appl. Mater. Interface 13(37), 43904–43913 (2021).

Antonel, P. S., Berhó, F. M., Jorge, G. & Molina, F. V. Magnetic composites of CoFe2O4 nanoparticles in a poly(aniline) matrix: Enhancement of remanence ratio and coercivity. Synth. Met. 199, 292–302. (2015).

Thang, P. D., Rjinders, G. & Blank, D. H. A. Spinel cobalt ferrite by complexometric synthesis. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 295, 251–256 (2005).

Williams, S. et al. Magnetizing cellulose fibers with CoFe2O4 nanoparticles for smart wound dressing for healing monitoring capability. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2, 5653–5662 (2019).

Bozorth, R. M., Tilden, E. F. & Williams, A. J. Anisotropy and magnetostriction of some ferrites. Phys. Rev. 99, 1788–1798 (1955).

Nlebedim, I. C. et al. Effect of temperature variation on the magnetostrictive properties of CoAlxFeO2-x4. J. Appl. Phys. 107, 09A936 (2010).

Chao, Z. et al. The phase diagram and exotic magnetostrictive behaviors in spinel oxide Co(Fe1-xAlx)2O4 system. Materials 12, 1685 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) (Grant Number 22H00183) and Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists (Grant Number 19K14836).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, K.H.; methodology, T.K.; formal analysis, T.K., L.R., A.G.--P.; investigation, T.K.; resources, H.K., F.N.; writing—original draft preparation, T.K.; writing—review and editing, T.K., L.R., A.G.--P., H.K., F.N.; visualization, H.K.; supervision, F.N.; project administration, H.K.; funding acquisition, H.K., F.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Keino, T., Rova, L., Gallet--Pandellé, A. et al. Negative magnetostrictive paper formed by dispersing CoFe2O4 particles in cellulose nanofibrils. Sci Rep 13, 6144 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31655-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31655-z

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.