Abstract

Hybrid polyvinylidene fluoride-silica-hexadecyltrimethoxysilane (PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS) membranes were fabricated via a non-solvent-induced phase-inversion method to create stable hollow-fiber membranes for use in the membrane contact absorption of carbon dioxide (CO2). The surface properties, performance characteristics, and long-term performance stability of the prepared membranes were compared and analyzed. The outer surfaces of the prepared membranes were superhydrophobic because of the formation of rough nanoscale microstructures on the surfaces and their low surface free energy. The addition of inorganic nanoparticles improved the mechanical strength of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS. Long-term stable operation experiments were carried out with a mixed inlet gas (CO2/N2 = 19/81, v/v) at a flow rate of 20 mL/min. The absorbent liquid in these experiments was 1 mol/L diethanolamine (DEA) at a flow rate of 50 mL/min. The mass transfer flux of CO2 through the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS membrane decreased from an initial value of 2.39 × 10–3 mol/m2s to 2.31 × 10–3 mol/m2s, a decrease of 3% after 20 days. The addition of highly stable and hydrophobic inorganic nanoparticles prevented pore wetting and structural damage to the membrane. The PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS membrane was found to have excellent long-term stable performance in absorbing CO2.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biogas is a promising renewable energy source1 that is mainly composed of CH4 (55–65%), CO2 (30–45%)2, and other trace gases. In order to use it as a fuel, its content of CH4 must be at least 95%, so the absorption of carbon dioxide (CO2) is of great significance for the practical application of biogas. Carbon dioxide (CO2) capture from biogas by hollow-fiber membrane contactor systems have been investigated by several researchers. In a membrane contactor system for CO2 absorption, the mixed gas and the liquid absorbent flow on opposite sides of the hollow-fiber membrane, and the CO2 in the gas is absorbed by the liquid absorbent after passing through the hollow-fiber membrane. The hollow-fiber membrane acts as a non-selective barrier between the liquid phase and the gas phase, separating the gas phase from the liquid phase and providing a large gas–liquid contact area. Studies have shown that in the process of membrane contact absorption, the absorbing liquid enters and wets the membrane pores3,4,5. The diffusion rate of CO2 in the gas is greater than in the liquid phase. This greatly increases the diffusion resistance of the membrane to CO2, resulting in a rapid decrease in the mass transfer flux of CO2. The hollow-fiber membrane must therefore be made hydrophobic.

During a membrane contact absorption process, the membrane will inevitably be wetted because the pressure of the liquid phase must be higher than the pressure of the gas phase to avoid the generation of bubbles. The transmembrane pressure difference thus drives absorbent into the pores, which wets the pores. By contrast, when a chemical absorbent is used, the surface properties (pore size, porosity, roughness, and chemical composition) of the membrane change because of the susceptibility of the polymer membrane material to erosion by alkaline liquids6,7,8. This increases the pore size of the membrane and decreases the surface contact angle, thus decreasing the hydrophobicity of the membrane. In addition, during long-term operation, vaporized liquid absorbent enters the membrane pores and wets them as the vapor condenses. Recent research has therefore focused on the development of superhydrophobic hollow-fiber membranes for the long-term stable operation of membrane contact absorption processes9,10.

In our previous studies, superhydrophobic hybrid polyvinylidene fluoride-hexadecyltrimethoxysilane (PVDF-HDTMS) membranes were fabricated via a non-solvent-induced phase-inversion method with a mixture of ammonia and water as the non-solvent additive and dehydrofluorination reagent and HDTMS as the hydrophobic modifier. A long-term CO2 membrane contact absorption experiment was conducted to investigate the long-term stability of the membrane under moderate alkaline conditions. The CO2 mass transfer flux of the PVDF-HDTMS membrane contactor was found to have decreased by only 17% and then remained stable over 17 days of membrane contact absorption with 1 mol/L diethanolamine (DEA) as the absorbent. Although the PVDF-HDTMS membranes were found to have the excellent long-term stability, current research suggests that further improvements are possible.

Studies have shown that using special methods to deposit hydrophobic inorganic nanoparticles on hollow-fiber membranes can result in superhydrophobic hollow-fiber membranes with excellent long-term stability11,12. Zhang et al.13 developed a highly hydrophobic organic–inorganic composite hollow-fiber membrane by incorporating a fluorinated silica inorganic (fSiO2) layer on a polyetherimide organic membrane substrate via a sol–gel process. The membrane contactor remained fairly stable over 31 days’ operation using a 2M aqueous sodium taurinate solution as the absorbent, with a 20% decrease from the initial CO2 flux. This is mainly because the incorporation of the fSiO2 inorganic layer resulted in high hydrophobicity and protected the polymeric substrate from attack by the chemical absorbent, thus increasing the lifetime of the membrane. Xu et al.14 fabricated an inorganic–organic fluorinated titania-silica (fTiO2–SiO2)/polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) composite membrane by forming a superhydrophobic SiO2–TiO2 inorganic layer on the PVDF membrane substrate via facile in situ vapor-induced hydrolyzation followed by hydrophobic modification. The CO2 absorption flux of the fTiO2–SiO2/PVDF composite hollow-fiber membrane decreased by merely 10% over the 31 days of the long-term test because its high chemical resistance and hydrophobicity effectively prevented corrosion of the PVDF substrate by the chemical absorbent monoethanolamine (MEA). This shows that the incorporation of hydrophobic inorganic nanoparticles into hollow-fiber membranes can increase the hydrophobicity and corrosion resistance of the membrane, thus improving the long-term performance of the membrane.

In this study, we describe the design and fabrication of polyvinylidene fluoride-silica-hexadecyltrimethoxysilane (PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS) composite membranes via a simple non-solvent-induced phase-inversion method using an ammonia-water mixture as a non-solvent additive and dehydrofluorination reagent, HDTMS as a hydrophobic modifier, and nano-SiO2 particles as inorganic filler. The physical and chemical properties of the prepared PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS film were characterized and the long-term stability for CO2 absorption was examined using DEA as an absorbent.

Experimental

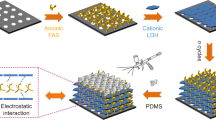

Formation mechanism of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS membranes

PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS membranes were fabricated in four steps. The first step (Fig. 1a,b) was to introduce oxygen-containing functional groups into PVDF molecules through defluorination and oxygenation reactions15 (Fig. 1e). In the second step (Fig. 1b,c), the hydroxyl groups on the PVDF chains reacted to form –O– bonds with most of the hydroxyl groups on the surface of the SiO2, thus forming PVDF-SiO2 dope (Fig. 1f). In the third step (Fig. 1c,d), HDTMS was added to the polymer solution, where it was hydrolyzed by the small amount of water in the solution to form silanol. Polycondensation then occurred between silanol molecules to form polysiloxane, which subsequently reacted with the hydroxyl groups in PVDF-SiO2.The mechanism by which HDTMS is grafted onto PVDF-SiO2 is shown in (Fig. 1g), where R represents a hexadecyl group. In the last step (Fig. 1h), PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS hollow-fiber membranes were fabricated by a non-solvent-induced phase-inversion process.

Materials

PVDF L-6020 in the form of pellet particle was purchased from Solvay Advance Polymers, USA, and used for the fabrication of the hollow fiber membranes. The reagents of N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP, ≥ 99.0% purity), ammonia water (25–28% purity, pH = 12–13), diethanolamine (DEA, 99.0% purity), and ethanol (≥ 99.7% purity) were supplied by Chengdu Kelong Inc., China. HDTMS was supplied by Aladdin Inc., China. Nano-SiO2 particles (The average particle size of is 50 nm, Hydrophilic) were supplied by Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd., China.

Fabrication of hollow fiber membrane and membrane contactor module

PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS hollow-fiber membranes were fabricated via a dry-jet wet-spinning phase-inversion method. The PVDF and SiO2 were dried in a vacuum oven at 70 ± 2 °C for 24 h, after which the dehydrated PVDF polymer particles were gradually added to a magnetically stirred mixture of NMP, ammonia, water, and SiO2 at 60 °C until the particles were completely dissolved. During this process, the solution gradually turned brown. After the solution was allowed to stand for 12 h, HDTMS was added and stirred at room temperature for another 12 h to form a homogenous dope. The dope was degassed under vacuum overnight before spinning. The compositions of each dope used in this study are shown in Table 1. The parameters of the spinning process are shown in Table 2. The fabricated hollow-fiber membranes were immersed in pure ethanol for 15 min immediately after the spinning process, subsequently stored in water for 3 days to remove NMP and additives, and then immersed in methanol for one day to protect the formed pores. Finally, the membranes were maintained at room temperature to evaporate the residual methanol. The performance of the membrane was compared to that of a previously described PVDF-PA-8 membrane that was fabricated without amine water treatment and the addition of inorganic nanoparticles16.

Characterization

The surface functional groups of the membranes were determined by the attenuated total reflectance-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) on a NEXUS 870, NICOLET, USA. The ATR-FTIR spectra were collected over a scanning range of 500–4000 cm−1 with 16 scans over 4.0 cm−1.

The morphology images and the EDS spectrum and mapping of the hollow fibers were observed by the scanning electron microscopy with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS) (Tabletop Microscope FEI Quanta 250 FEG, USA). The cross section was obtained by fracturing each membrane in liquid nitrogen. The samples were sputtered with gold for 15 s at 40 mA current before the test. The samples of the EDS were sputtered with gold for 15 s at 40 mA current before the test.

A sessile drop technique using a goniometer (Shanghai Zhongchen Digital Technology Instrument Corporation Limited, JC2000D1, China) was used to measure the contact angles of the outer surface of the membranes. For each measurement, 3 μL of pure water or 1M DEA was pumped out from a syringe. The liquid drop remained on the membrane outer surface for 3 min before recording, and the result was adopted as the average value of ten measurements for each sample.

The nitrogen (N2) gas permeation test was conducted to obtain the mean pore size and effective surface porosity. The wettability resistance of the prepared membrane was assessed by measurements of the critical water entry pressure (CEPw). The measurement method of the nitrogen (N2) gas permeation and CEPw were referred to literature17,18,19.

The tensile strength and elongation at break were measured using a tensile test device (Japan Shimadzu AGS-J) to evaluate the mechanical properties of the membranes. The test was conducted at room temperature and the testing speed was set at 10 mm/min16.

CO2 contact absorption experiment

CO2 absorption experiments process and the experimental setup could refer to our previous study17. The corresponding parameters for the experiments are shown in Table 3. Before each test, the system was operated for at least 30 min to obtain a steady state. The CO2/N2 mixture (19 vol.% CO2) was served as the feed gas flowing through the lumen side of the membranes, and the aqueous DEA solution of 1 mol/L was employed as the liquid absorbent flowing through the shell side of the membranes counter-currently. The flowrate of inlet gas was controlled at 20 mL/min by a gas rotameter, and the flowrate of absorption liquid was controlled by a constant flow pump at 50 mL/min. In order to prevent gas bubbles into the liquid phase, the pressure in the liquid side was controlled 20 kPa higher than that in the gas side. The concentrations of CO2 in the inlet and outlet gas were measured by the CO2 detector (MIC-800, Shenzhen Yiyuntian electronics technology Co. Ltd., China). The equation to calculated CO2 absorption flux of the PVDF membranes referred to our previous article17.

Results and discussion

Membrane surface chemical structure

Figure 2 shows the ATR-FTIR spectra of the outer layers of the fabricated membranes and of the PVDF-PA-8 membrane (without the grafting treatment described in our previous work16). Compared with the PVDF-PA-8 membrane, two new bands were observed at 2917 and 2849 cm−1 in the ATR-FTIR spectra of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS and PVDF-HDTMS membrane outer layers. These bands are ascribed to the stretching of methylene groups (CH2) in the HDTMS chains and show that HDTMS was successfully grafted onto the outer surfaces of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS and PVDF-HDTMS membranes. The absence of a signal from the Si–O–Si functional groups on the outer surface of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS membrane may be due to its characteristic band coinciding with that of PVDF.

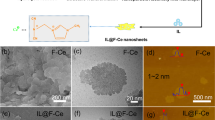

Morphology of a hollow fiber membrane

Figure 3 shows SEM images of the prepared hollow-fiber membranes and PVDF-PA-8 membrane. For PVDF, a semi-crystalline polymer, the wet process for the preparation of the hollow-fiber membranes results in the membrane being formed mainly by liquid–liquid or solid–liquid stratification. The bath conditions play an important role in determining the membrane structure20,21. Pure ethanol was used as the external coagulation bath and water as the core fluid in the preparation of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS and PVDF-HDTMS membranes. In the PVDF-PA-8 membrane preparation process, water and 80% NMP aqueous solution were respectively used as the external coagulation bath and the core fluid. Figure 3 shows that the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS and PVDF-HDTMS membranes had no outer skin layers but that they each had an inner skin layer. The outer surfaces of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS and PVDF-HDTMS membranes were mainly composed of spherulitic structures, while the inner and outer skin structures of PVDF-PA-8 are just the opposite. This was mainly due to the use of “soft” pure ethanol and 80% NMP aqueous solution in the coagulation bath. The exchange rate between solvent and non-solvent is lower during the phase transfer during the spinning process than after the polymer crystallization process, so solid–liquid stratification leads to form spherulite structures.

Further observation revealed that the outer surface of the PVDF-HDTMS membrane had a honeycomb spherulitic structure (Fig. 3b), while the spherulite structure of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS membrane outer surface was covered with lumps (Fig. 3a) that may have been caused by the accumulation of a large amount of SiO2.

Because PVDF is hydrophobic and nano-SiO2 is hydrophilic, SiO2 will disperse poorly and agglomerate in the casting solution upon blending as a result of the interfacial tension between the hydrophobic and hydrophilic inorganic materials22. The EDS analysis of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS and PVDF-HDTMS membrane was displayed in Fig. 4, according to the EDS spectra, it can be found that Si element was the evenly distributed on the outer surface (the results of EDS analysis are consistent with those of ATR-FTIR). Therefore, the SiO2 distribution on the cross-section of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS membrane is uniform, and Fig. 3 shows that no significant agglomeration was observed. This was due to the introduction of hydroxyl groups into the PVDF chains in the ammonia–water mixture22, which resulted in enhanced affinity between the PVDF chains and the hydrophilic nano-SiO2 particles.

Gas permeability and hydrophobicity of the hollow fiber membranes

The gas permeabilities of the membranes were determined using N2 permeation tests (Table 4), as were previous results for the PVDF-PA-8 membrane16. And the data of N2 permeation can be viewed in supplementary material 1. The PVDF-PA-8 membrane had the lowest N2 permeability of the samples tested. This is because the large number of sponge-like structures in its cross-section increase the tortuosity of the PVDF-PA-8 membrane relative to the other two membranes23. The decrease in the nitrogen permeability of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS membrane may be due to the addition of inorganic nanoparticles that blocked the membrane pores, resulting in the N2 permeability of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS membrane being slightly lower than that of the PVDF-HDTMS membrane. For a porous asymmetric membrane, the overall gas permeance through the membrane can be treated as a combination of Poiseuille flow and Knudsen flow24. Assuming that the pores in the skin layer of the asymmetric membranes are cylindrical and plotting N2 permeance versus mean pressure, the mean pore sizes and the effective surface porosities over the pore lengths of the membranes are respectively given by the intercept and slope of the plot25. The calculated effective surface porosities and average pore sizes of the membranes are shown in Table 4. The surface pore sizes and surface porosities of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS and PVDF-HDTMS membranes were higher than those of PVDF-PA-8 because the open membrane structure without an outer skin provides larger pore size and surface porosity. The parameters CEPW and outer surface contact angle, which are correlated to the long-term stability of the membranes, are also shown in Table 4. Compared with the PVDF-HDTMS membrane, the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS membrane had significantly higher CEPW and a higher outer surface contact angle. Therefore, the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS membrane is preferable for CO2 absorption in membrane contactors.

During the preparation process, the strength of the PVDF chain decreased because of defluorination by ammonia, resulting in the fabricated membranes having lower mechanical strength. Therefore, as shown in Table 4, the tensile strengths and elongations at break of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS and PVDF-HDTMS membranes were lower than those of the PVDF-PA-8 membrane. However, the tensile strength and elongation at break of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS membrane were higher than those of the PVDF-HDTMS membrane. This is mainly due to the formation of Si–O–Si bonds between SiO2 and PVDF and between SiO2 and HDTMS, which increased the molecular bonding forces between the three and thereby increased the tensile strength and elongation at break of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS membrane.

Long-terms performance of the membranes

A long-term CO2 membrane contact absorption experiment was conducted using 1 mol/L DEA as the absorbent to investigate the long-term stability of the membranes under moderately alkaline conditions. The results are shown in Fig. 5. The PVDF-PA-8 membrane was completely wetted after 10 days, and the mass transfer flux was reduced by 31.5%. The CO2 mass transfer flux of the PVDF-HDTMS membrane decreased by 17% after 20 days. The PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS membrane showed excellent long-term stability even in alkaline solution: the CO2 mass transfer flux decreased from an initial value of 2.39 × 10−3 mol/m2s to 2.31 × 10−3 mol/m2s, a reduction of only 3%.

Long-term CO2 absorption performance of the membranes (The data of Long-term CO2 absorption performance of the membranes can be viewed in Supplementary material 2).

The ability of the PVDF-PA-8 membrane to withstand wetting is mainly determined by its large cross-sectional tortuosity and its small surface pore size. However, the membrane’s wetting resistance to alkaline solution is poor because of its low hydrophobicity, which results in poor long-term stability.

The PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS and PVDF-HDTMS membranes are similar in terms of parameters such as average pore size, surface effective porosity, and surface contact angle, so their anti-wetting performance and air permeability are similar. Little difference was initially observed in these membranes’ mass fluxes of CO2. However, over the long term, the performance of the PVDF-HDTMS membrane degraded more than that of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS membrane. This may be related to the tensile strengths of the membranes. Although the tensile strength of PVDF-HDTMS membrane was sufficient for use in membrane contact absorption, it was lower than that of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS membrane. In the course of long-term operation, the PVDF-HDTMS membrane eroded more in the alkaline solution, leading to more rapid performance degradation.

The chemical stability of the composite membrane

In the process of membrane contact absorption, long-term contact between the membrane and the chemical absorbent results in a chemical reaction occurring between the surface of the membrane and the chemical absorbent, causing deterioration in the long-term stability of the membrane and decreasing its CO2 mass transfer flux. To verify the long-term corrosion resistance of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS hollow-fiber membranes to chemical absorbents, nitrogen permeation (The data of N2 permeation can be viewed in supplementary material 3) and contact angle experiments were conducted to characterize the performance of the hollow-fiber membranes after 20 days’ stable operation.

The surface pore size and porosity of the three types of membranes after 20 days’ operation are shown in Table 5. The surface pore size and porosity calculations (Table 5) showed large changes in the surface pore sizes and porosities of the three types of membranes. This indicates that DEA did not have much effect on the surface morphologies of the membranes. The contact angles of the three types of membranes decreased after 20 days’ long-term operation in the order PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS < PVDF-HDTMS < PVDF-PA-8. The work of Sadoogh et al.26 suggests that the degradation of PVDF membrane performance may be due to chemical degradation of the interface between PVDF and MEA, which leads to the dehydrogenation and fluorination of the PVDF surface. Therefore, the reason for the smaller decrease in the contact angle of PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS was that the large amounts of chemically stable, superhydrophobic SiO2 grafted onto the surface of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS membrane effectively prevented the PVDF substrate from contact with the DEA solution. The corrosion in the medium ensured the long-term stable operation of the membrane. Xu et al.14 prepared membranes with superhydrophobic f-TiO2–SiO2 layers on their outer surfaces, while Zhang et al.13 prepared membranes with superhydrophobic f-SiO2 layers on their outer surfaces. Both groups obtained similar results, which shows that grafting superhydrophobic metal nanoparticles onto the outer surface of the membrane is effective in preventing the chemical corrosion of PVDF by chemical absorbents, thus increasing the chemical corrosion resistance of the membrane.

In Table 6, the parameters of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS membrane are compared with those of other hydrophobic membranes reported by other research groups. The carbon dioxide absorption fluxes and long-term stability results in Table 6 clearly show that the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS membrane described in this study is competitive in terms of CO2 absorption flux as well as long-term stability when absorbent alkalinity and flow rate are moderate and CO2 concentration is low. The PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS membrane can maintain high performance and stability while showing excellent CO2 absorption flux. The main reason is to graft a large number of superhydrophobic SiO2 with high hydrophobicity and chemical stability on the membrane surface, effectively prevent the corrosion of PVDF membrane in in the chemical absorber, and ensure the long-term stable operation of the membrane.

Conclusions

In this study, hydrophilic nano-SiO2 was added as an inorganic filler to a casting solution, and ammonia was used as a defluorinating agent to hydroxylate PVDF molecules and generate active sites. With the addition of hydrophilic nano-SiO2, the hydroxyl groups formed on the PVDF molecule undergo a dehydration reaction to form PVDF-SiO2 polymer chain. HDTMS was then added to modify the hydrophobicity. Superhydrophobic PVDF-SiO2 with high tensile strength was prepared by spinning by the NIPS method to create an HDTMS organic–inorganic composite membrane. The prepared membrane had a maximum CO2 mass transfer flux of 2.39 × 10−3 mol/m2s. After 20 days of membrane contact absorption with 1 mol/L DEA as the absorbent, the CO2 mass transfer flux of the membrane contactor decreased by only 3%. Large quantities of superhydrophobic, chemicaelly stable SiO2 grafted onto the surface of the PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS film were effective in preventing the corrosion of the PVDF substrate in DEA solution. The film was superhydrophobic, with strong resistance to wetting and chemical stability.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Weiland, P. Biogas production: Current state and perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 85, 849–860. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-009-2246-7 (2010).

Xu, Y., Li, X., Lin, Y., Maldec, C. & Wang, R. Synthesis of ZIF-8 based composite hollow fiber membrane with a dense skin layer for facilitated biogas upgrading in gas–liquid membrane contactor. J. Membr. Sci. 585, 238–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2019.05.042 (2019).

Lv, Y. et al. Fabrication and characterization of superhydrophobic polypropylene hollow fiber membranes for carbon dioxide absorption. Appl. Energy 90(1), 167–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2010.12.038 (2012).

Zhang, Y., Sunarso, J., Liu, S. & Wang, R. Current status and development of membranes for CO2/CH4 separation: A review. Int. J. Greenh. use Gas Control 12, 84–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2012.10.009 (2013).

Khaisri, S., Demontigny, D., Tontiwachwuthikul, P. & Jiraratananona, R. A mathematical model for gas absorption membrane contactors that studies the effect of partially wetted membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 347(1–2), 228–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2009.10.028 (2010).

Mosadegh-Sedghi, S., Rodrigue, D., Brisson, J. & Iliuta, M. C. Wetting phenomenon in membrane contactors–causes and prevention. J. Membr. Sci. 452, 332–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2013.09.055 (2014).

Wang, R., Zhang, H. Y., Feron, P. H. M. & Liang, D. T. Influence of membrane wetting on CO2 capture in microporous hollow fiber membrane contactors. Sep. Purif. Technol. 46(1–2), 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2005.04.007 (2005).

Huang, A., Chen, L. H., Chen, C. H., Tsai, H. Y. & Tung, K. L. Carbon dioxide capture using an omniphobic membrane for a gas–liquid contacting process. J. Membr. Sci. 556, 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2018.03.089 (2018).

Xu, Y., Goh, K., Wang, R. & Bae, T.-H. A review on polymer-based membranes for gas-liquid membrane contacting processes: Current challenges and future direction. Sep. Purif. Technol. 229, 115791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2019.115791 (2019).

Li, Y., Wang, L., Hu, X., Jin, P. & Song, X. Surface modification to produce superhydrophobic hollow fiber membrane contactor to avoid membrane wetting for biogas purification under pressurized conditions. Sep. Purif. Technol. 194, 222–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2017.11.041 (2018).

Ahmad, A. L., Mohammed, H. N., Ooi, B. S. & Leo, C. P. Deposition of a polymeric porous superhydrophobic thin layer on the surface of poly(vinylidenefluoride) hollow fiber membrane. Pol. J. Chem. Technol. 15, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.2478/pjct-2013-0036 (2013).

Wu, X. et al. Superhydrophobic PVDF membrane induced by hydrophobic SiO2 nanoparticles and its use for CO2 absorption. Sep. Purif. Technol. 190, 108–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2017.07.076 (2018).

Zhang, Y. & Wanga, R. Novel method for incorporating hydrophobic silica nanoparticles on polyetherimide hollow fiber membranes for CO2 absorption in a gas-liquid membrane contactor. J. Membr. Sci. 452, 379–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2013.10.011 (2014).

Xu, Y., Lin, Y., Lee, M., Malde, C. & Wang, R. Development of low mass-transfer-resistance fluorinated TiO2-SiO2/PVDF composite hollow fiber membrane used for biogas upgrading in gas–liquid membrane contactor. J. Membr. Sci. 552, 253–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2018.02.016 (2018).

Brewis, D. M., Mathieson, I., Sutherland, I., Cayless, R. A. & Dahm, R. H. Pretreatment of poly(vinyl fluoride) and poly(vinylidene fluoride) with potassium hydroxide. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 16, 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/0143-7496(95)00053-4 (1996).

Honglei, P., Gong Huijuan, Du., Mengfan, S. Q. & Zezhi, C. Effect of non-solvent additive concentration on CO2 absorption performance of polyvinylidenefluoride hollow fiber membrane contactor. Sep. Purif. Technol. 191, 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2017.09.012 (2018).

Pang, H., Chen, Z., Gong, H. & Du, M. Fabrication of a super hydrophobic polyvinylidene fluoride-hexadecyltrimethoxysilane hybrid membrane for carbon dioxide absorption in a membrane contactor. J. Membr. Sci. 595, 117536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2019.117536 (2020).

Naim, R., Ismail, A. F. & Mansourizadeh, A. Preparation of microporous PVDF hollow fiber membrane contactors for CO2 stripping from diethanolamine solution. J. Membr. Sci. 392, 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2011.11.040 (2012).

Mansourizadeh, A. & Ismail, A. F. Preparation and characterization of porous PVDF hollow fiber membranes for CO2 absorption: Effect of different non-solvent additives in the polymer dope. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 5, 640–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2011.03.009 (2011).

Ahmad, A. L., Ramli, W. K. W., Fernando, W. J. N. & Daud, W. R. W. Effect of ethanol concentration in water coagulation bath on pore geometry of PVDF membrane for Membrane Gas Absorption application in CO2 removal. Sep. Purif. Technol. 88, 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2011.11.035 (2012).

Chang, H. H., Chang, L. K., Yang, C. D., Lin, D. J. & Cheng, L. P. Effect of polar rotation on the formation of porous poly(vinylidene fluoride) membranes by immersion precipitation in an alcohol bath. J. Membr. Sci. 513, 186–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2016.04.052 (2016).

Vatanpour, V., Madaenia, S., Moradian, R., Sirus, Z. & Astinchap, B. Fabrication and characterization of novel antifouling nanofiltration membrane prepared from oxidized multiwalled carbon nanotube/polyethersulfone nanocomposite. J. Membr. Sci. 375(1–2), 284–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2011.03.055 (2011).

Rezaei, M., Ismail, A. F., Hashemifard, S. A. & Matsuurac, T. Preparation and characterization of PVDF-montmorillonite mixed matrix hollow fiber membrane for gas-liquid contacting process. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 92, 2449–2460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cherd.2014.02.019 (2014).

Henis, J. M. S. & Tripodi, M. K. Composite hollow fiber membranes for gas separation: The resistance model approach. J. Membr. Sci. 8, 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0376-7388(00)82312-1 (1981).

Mansourizadeh, A. & Ismail, A. F. A developed asymmetric PVDF hollow fiber membrane structure for CO2 absorption. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 5, 374–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2010.09.007 (2011).

Sadoogh, M., Mansourizadeh, A. & Mohammadinik, H. An experimental study on thestability of PVDF hollow fiber membrane contactors for CO2 absorption with alkanolamine solutions. RSC Adv. 5, 86031–86040. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5ra15263a (2015).

Wang, L. et al. Hydrophobic polyacrylonitrile membrane preparation and its use in membrane contactor for CO2 absorption. J. Membr. Sci. 569, 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2018.09.066 (2019).

Rahbari-Sisakht, M., Ismail, A. F., Rana, D., Matsuura, T. & Emadzdeh, D. Effect of SMM concentration on morphology and performance of surface modified PVDF hollow fiber membrane contactor for CO2 absorption. Sep. Purif. Technol. 116, 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2013.05.008 (2013).

Zhang, Y. & Wang, R. Fabrication of novel polyetherimide-fluorinated silica organic–inorganic composite hollow fiber membranes intended for membrane contactor application. J. Membr. Sci. 443, 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2013.04.062 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial supports from the Qing Lan Project of Jiangsu Province.

Funding

Funding was provide by Qinglan Project of Jiangsu Province of China (Grant No. 202050220RS005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Honglei Pang wrote the main manuscript text. Honglei Pang completed the preparation of the membrane, Honglei Pang, Yayu Qiu and Weipeng Sheng completed the experiment. Yayu Qiu prepared figures 1-8 and Weipeng Sheng prepared tables 1-6. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pang, H., Qiu, Y. & Sheng, W. Long-term stability of PVDF-SiO2-HDTMS composite hollow fiber membrane for carbon dioxide absorption in gas–liquid contacting process. Sci Rep 13, 5531 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31428-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31428-8

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.