Abstract

Although some studies have shown the association between sleep duration and cognitive impairment is positive, the mechanism explaining how sleep duration is linked to cognition remains poor understood. The current study aims to explore it among Chinese population. A cross-sectional study of 12,589 participants aged 45 or over was conducted, cognition was assessed by three measures to capture mental intactness, episodic memory, and visuospatial abilities. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale 10 (CES-D10) was administered during the face-to-face survey to assess depressive status. Sleep duration was reported by the participants themselves. Partial correlation and linear regression were used to explore the association between sleep duration, cognition, and depression. The Bootstrap methods PROCESS program was used to detect the mediation effect of depression. Sleep duration was positively correlated with cognition and negatively with depression (p < 0.01). The CES-D10 score (r = − 0.13, p < 0.01) was negatively correlated with cognitive function. Linear regression analysis showed sleep duration was positively associated with cognition (p = 0.001). When depressive symptoms were considered, the association between sleep duration and cognition lost significance (p = 0.468). Depressive symptoms have mediated the relationship between sleep duration and cognitive function. The findings revealed that the relationship between sleep duration and cognition is mainly explained by depressive symptoms and may provide new ideas for interventions for cognitive dysfunction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development of society, the prevalence of cognitive dysfunction has been gradually rising1 and is a crucial public health issue in China. In 2011, national figures showed that 9% of elderly individuals had cognitive impairment2. In 2016, a meta-analysis suggested that the pooled prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in the Chinese population had increased to 14.71%3. Cognitive impairment is associated with an increased risk for disability and economic burden and is an essential element of the diagnostic criteria for dementia4,5. Therefore, cognitive impairment is a significant burden on patients, their families, or society6.

Various factors affect cognitive impairment, such as ApoE4 status, smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular disease, and physical, intellectual, and social activities7,8,9. Furthermore, research on sleep and health has become active in recent years. Sleep duration plays a vital role in protecting individuals from cognitive decline10. Short sleep duration was associated with greater age-related brain atrophy and cognitive decline among old adults. Each 1-h decrease in sleep duration could predict a 0.67% greater annual decrease in global cognitive performance11. In addition, several studies have revealed a U-shaped association between sleep duration and cognitive impairment, and both shorter and longer sleep durations have been related to a higher risk of cognitive disorders12,13,14. However, the relationship between sleep duration and cognitive function in middle-aged and elderly individuals is still unclear.

Sleep duration has also been commonly associated with depression15. Several studies have reported that short sleep durations exacerbate depressive symptoms16. A meta-analysis indicated that short and long sleep duration was significantly associated with an increased risk of depression in adults17. There was a curvilinear relation between sleep duration and depression, such that both short and long sleep durations were associated with depression18. Moreover, severe depression was associated with a relatively faster rate of cognitive decline among middle-aged and old adults19,20,21.

The links between sleep duration, depression, and cognitive function are interrelated. Depression was shown to mediate the relationship between short sleep duration and life satisfaction22. What then is the relationship between sleep duration, depression, and cognitive function? The current study sought to examine the mediating effect of depression on the relationship between sleep duration and cognitive function in Chinese adults. We hypothesized that sleeping for a long enough duration is associated with better cognitive function and that this association would be mediated at least in part by depression.

Methods

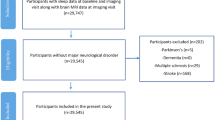

Study sample

The data were from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) survey that targeted middle-aged and elderly individuals (45 + years of age) in China. The CHARLS is an ongoing follow-up study with exams performed every 2 years for a total of 3 waves from 2011 to 2015, which provided a broad range of information from demographic characteristics to health status23,24. The detailed sampling process can be found elsewhere25. In summary, the baseline survey was fielded from June 2011 to March 2012 and involved 17,705 respondents randomly selected with a probability proportional to scale (PPS) in 450 villages/resident committees, 150 counties/districts, and 28 provinces. A face-to-face interview was conducted via computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) technology.

In this study, we adopted the data from wave 1, and a final sample of 12,589 respondents was included in the analysis. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) had complete data related to sleep duration; (ii) had complete data related to cognition measures at baseline; and (iii) had marital status, residency, smoking, drinking, body mass index (BMI), hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes or high blood sugar data at baseline. The exclusion criteria were: (a) unconsciousness caused by any forms; (b) any obvious cognitive disabilities or deafness, aphasia, or other language barriers; and (c) sleep disorders and taking hypnotics, as well as some particular work needed to going to bed late.

This study was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Review Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052-11015) and the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee (H-2015-0290). All interviewees were required to sign informed consent.

Outcome variable

Cognitive function was assessed using three measures at baseline: (a) the Telephone Interview of Cognitive Status (TICS-10); (b) word recall (WR); and (c) figure drawing (FD)23,26. These were used to estimate cognitive domains of mental intactness (orientation to time and attention), episodic memory, and visuospatial abilities. The overall cognitive score was calculated as the sum score of the TICS-10 (a sum of 10 scores), WR (a sum of 10 scores), and FD (a sum of 1 score) and could range from 0 to 21. The TICS-10 includes 10 items (score ranges from 0 to 10) that estimate the intactness of mental health, including orientation to time and attention26. The WR test assesses episodic memory and is the average number of correct immediate and delayed recalls from a list of 10 Chinese nouns24,26. The total score on the WR is 10. The FD test was used to measure visuospatial abilities24. The participants were shown two overlapping pentagons for this test and asked to draw the same picture. Scores of “1” and “0” indicate participants who successfully finished and failed the task, respectively.

Independent variable

Sleep duration was obtained via the following question. “During the past month, how many hours of actual sleep did you get at night (average hours for one night)? (This may be shorter than the number of hours you spend in bed)”.

The Chinese version of the 10-item short form of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D10)27 was employed to indicate depressive symptoms, which has been validated among elderly individuals in China28,29. Ten items were contained in the CES-D10, and each item was scored from 0 to 3 in response to a 4-point Likert scale (from ‘rarely or none of the time’ to ‘most or all of the time’). The total score can range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating higher levels of depression. A cut-off score ≥ 10 was used to distinguish the participants who had obvious depressive symptoms30. A previous study showed that the CES-D10 scale has good reliability and validity (Cronbach’s α = 0.81)31.

Other covariates

Covariates included age, sex (male vs. female), educational level (illiterate, primary school, or junior high school and above), marital status (married, cohabitating and divorced, separated, widowed, or never married), residency (rural vs. urban), BMI (continuous data), smoking, drinking, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes or high blood sugar. Smoking status was measured with the question, “Have you ever chewed tobacco, smoked a pipe, smoked self-rolled tobacco or smoked cigarettes/cigars,” and the possible answers included the following 3 options: (1) Yes; (2) No, or (3) Quit. Alcohol consumption status was measured with the question, “Did you drink any alcoholic beverages, such as beer, wine, or liquor in the past year, and if so, how often?”, and the possible answers included the following: (1) Drink more than once a month; (2) Drink but less than once a month; or (3) Do not drink. The status of hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes or high blood sugar was estimated with the following question: “Have you been diagnosed with the conditions listed below by a doctor?”.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Means and standard deviations or frequency percentages were used to describe variables. Partial correlations were performed after controlling for age, sex, education, marital status, residency, smoking, drinking, BMI, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, or high blood sugar. A linear regression model was used to examine the association between sleep duration, depressive symptoms, and cognitive function. Bootstrapping methods of PROCESS developed by Hayes32 were employed to examine the mediation effect of depressive symptoms on the relationship between sleep duration and cognitive function. In the PROCESS procedure, the number of models chosen was 4, the bootstrap sample was set to 5000, and the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap confidence interval was used to evaluate the effect size. If the confidence interval does not contain 0, it would indicate that the mediation effect was statistically significant33. Sensitivity analyses were performed using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) approach.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for the study was granted by the Ethics Review Committee of Peking University, and all the participants provided signed informed consent at the time of participation. The study methodology was carried out in accordance with approved guidelines.

Results

Demographic characteristics

As shown in Table 1, approximately half of the participants were male, and approximately 1/5 were illiterate. Most (73.1%) were rural residents. Overall, 45.9% of the participants had depressive symptoms. The average age was 67.5 (SD = 9.6) years, with a range of 45 to 105 years. The average sleep duration was 6.4 (SD = 1.8) hours, the average CES-D10 score was 9.8 (SD = 4.7), and the average cognitive function score was 8.1 (SD = 2.8).

Correlation analysis

After controlling for covariates, sleep duration was positively correlated with cognitive function (r = 0.03, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.05, P < 0.01) and inversely associated with depression scores (CES-D10; r = − 0.24, 95% CI − 0.26 to − 0.22, P < 0.01). CES-D10 scores were negatively correlated with cognitive function (r = − 0.13, 95% CI − 0.15 to − 0.10, P < 0.01), as shown in Table 2. As shown in Fig. 1, an inverted U-shaped association between sleep duration and cognitive function was found. Meanwhile, a U-shaped association between sleep duration and depressive symptoms was also found (Fig. 2).

Linear regression analyses

As shown in Table 3, sleep duration was positively correlated with cognitive function (Model 1). When depressive symptoms were added in Model 2, the association between sleep duration and cognitive function lost significance (β = − 0.06, 95% CI − 0.22 to 0.10, P = 0.468).

Mediation

For this analysis, sleep duration was an independent variable, depressive symptoms were the mediator variable, and cognitive function was a dependent variable. After controlling for age, sex, education, marital status, residency, smoking, drinking, BMI, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes or high blood sugar, a mediation model was conducted. The total effect, direct effect, and mediating effect of sleep duration on cognitive function with standard errors and confidence intervals were obtained using the bootstrap method. The results showed that the direct effect was non-significant, while the total effect and the indirect effect were significant, indicating that depressive symptoms fully mediated the relationship between sleep duration and cognitive function. The mediation effect of depressive symptoms on the relationship between sleep duration and cognitive function accounted for 93.0% (0.040/0.043) of the total effect (Table 4). The bias-corrected program test results indicated that the 95% confidence interval was 0.033 to 0.047, a range that did not include 0, indicating that the mediation path was statistically significant. Considering the possible relationship between age and depressive symptoms, the exploring analysis conducted stratified (use a cutoff point of 60 years old) by age showed in Table 5. The mediation effect of depressive symptoms on the relationship between sleep duration and cognitive decline persists in those who < 60 and ≥ 60 years old.

Sensitivity analysis

As showed in Fig. 3, the SEM approach was conducted to sensitivity analysis. The results showed sleep duration was positively associated with cognitive function and inversely related to depressive symptoms, and depressive symptoms were negatively associated with cognitive function. These results were consistent with the binary correlation results even though the pathway coefficient was not the same due to the different methods. This validated the methodological robustness of the findings.

Discussion

The current study explored the association between sleep duration and cognitive function and the mediating effect of depressive symptoms on this relationship among middle-aged and elderly individuals in mainland China. In this study, we found that a longer enough sleep duration (in our population, only 956 (7.5%) participants reported sleeping ≥ 9 h per night) was associated with a reduced risk of cognitive decline, and these beneficial effects were mediated by depressive symptoms. The mediation effect accounted for 93.0% of the total effect.

Sleep duration was positively associated with cognitive function scores, and these data implied that short sleep duration might be a risk factor for cognitive impairment, consistent with a study showing that women sleeping for short durations had worse global cognition than those sleeping longer34. Short sleep duration was also reported to be a risk factor for cognitive impairment11,35. We speculate that the mechanism may be that short sleep duration has been related to the β-amyloid (Aβ) burden, which is one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease36. In addition, shorter sleep durations were associated with a greater degree of age-related brain atrophy11. However, our results were conflicted with prior research indicating that long sleep durations have been associated with cognitive impairment37,38. They explained this phenomenon by the fact that increased sleep fragmentation is associated with decreased cognitive performance and that longer sleep durations may result in more frequent nighttime awakenings or more sleep-in-bed time39. It should be noted that the r-value between sleep duration and cognitive function is somehow very small (r = 0.03); this maybe because there existed an inverted-U-shaped relationship between sleep duration and cognitive function. Previous research has reported that short or long sleep durations were significantly associated with memory impairment, might be a key marker for increased risk of cognitive impairment, and showed a U-shaped association14, which further confirmed that sleeping for enough duration was essential for maintaining cognitive function.

Furthermore, our results showed that depressive symptoms mediated the relationship between sleep duration and cognitive function. Previous studies have confirmed that depressive symptoms mediated the relationships between sleep duration and several factors, such as life satisfaction22. The present findings are also supported by a study showing that depression mediated the relationship between religiosity and cognitive impairment in older adults40. The relationships between sleep duration and depression have undoubtedly attracted people’s attention. The current study found that sleep duration was inversely associated with depression and implied that short sleep duration may be a risk factor for depression. This was consistent with a previous study that revealed that poor sleep, including short sleep duration, was independently associated with depression41. A meta-analysis also indicated that short sleep duration was linked to an increased risk of depression among adults16. Furthermore, we also found a U-shaped relationship between sleep duration and depressive symptoms, which is consistent with a previous study, that reported that insufficient or prolonged sleep was independently associated with depressive symptoms in middle-aged and elderly people, showing a U-shaped relationship42. Our study found that CES-D10 scores were negatively associated with cognitive function scores; that is, depression was positively associated with an increased risk of cognitive impairment. Previous studies have also suggested that depression was positively associated with cognitive impairment43,44. Furthermore, depression in elderly patients appears to predict dementia strongly45. These results might indicate that short sleep durations are associated with cognitive function through the mediating role of depression. In light of previous research, possible reasons are that shorter sleep duration may lead to daytime tiredness, which may lead to increased negative events and emotions, which may lead to depression46.

By the way, it was found that 45.9% of the participants had depressive symptoms. This significantly exceeds the data on the prevalence of depression in the general population. It may be that the percentage of depressive symptoms reported by previous studies were different because of the different participants, methods, and design or different measurement scales, etc. for example, the results from a systematic review and meta-analysis showed that the summary prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms among medical students estimates ranged across assessment modalities from 9.3% to 55.9%47. The prevalence of depressive symptoms among Chinese rural residents was 34.0%48. In addition, in our study, we defined the variable as depressive symptoms not depression when using the CES-D scale (CES-D score ≥ 10). Another study also reported that a large sample of Tibetan people with depressive symptoms (scores ≥ 8) accounted for 52.3% of the total sample, and participants with depression (scores ≥ 14) accounted for 28.6%49. In addition, the average sleep duration for the Chinese population was 6.4 (SD = 1.8) hours. It looks less than the recommended and differs from the data on the habitual sleep time from Europe or the United States. In our study, the average age of participants was 67.5 (SD = 9.6) years. The old adults usually had short sleep duration. A study showed that participants aged 63.3 slept ≤ 7 h accounted for 84.6%50. Besides, it may be the characteristics of the population sample.

Given the increasing proportion of aged individuals and increasing prevalence of dementia in the Chinese population, the strength of the present findings is its relevance for using large-sample data sets to understand the mechanisms underlying the effects of sleep duration on cognitive function, which may stimulate further research. Several limitations existed in the present study. First, this was a cross-sectional analysis, and causal inferences were not possible. Hence, a future study with a longitudinal design would be necessary to determine causal relationships. Second, sleep duration was collected based on self-reporting, which may involve information bias despite common use in epidemiological studies due to feasibility considerations. Meanwhile, the current study does not determine the cause/nature of short sleep duration, which may include sleep apnea, pain, or other sleep-related disorders. Third, a limited number of neuropsychological test variables were used in this study, as the three tests do not encompass most cognitive domains, which may affect the results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides evidence for the relationship between sleep duration and cognitive function among middle-aged and elderly individuals, suggesting a possible mechanism to explain how sleep duration is related to reduced cognition in studies examining that association. We found that depressive symptoms may mediate the relationship between sleep duration and cognitive impairment. Hence, in the clinic, clinicians may suggest that patients ensure that they get enough sleep and maintain a good mood. Clinicians may use melatonin to improve the sleep quality of those experiencing cognitive dysfunction and can also consider cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in a Supplementary File.

Abbreviations

- CES-D:

-

The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale

- TICS:

-

The telephone interview of cognitive status

- WR:

-

Word-recall

- FD:

-

Figure-drawing

References

Tang, H. D. et al. Prevalence and risk factor of cognitive impairment were different between urban and rural population: A community-based study. J Alzheimers Dis. 49, 917–925. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-150748 (2016).

Xue, J., Li, J., Liang, J. & Chen, S. The prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in China a systematic review. Aging Dis. 9, 706–715. https://doi.org/10.14336/AD.2017.0928 (2018).

Yin, P. et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cognitive impairment in the Chinese elderly population: A large national survey. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 11, 399–406. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S96237 (2016).

Plassman, B. L. et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment without dementia in the United States. Ann. Intern. Med. 148, 427–434. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00005 (2008).

Rait, G. et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment: Results from the MRC trial of assessment and management of older people in the community. Age Ageing 34, 242–248. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afi039 (2005).

Mitchell, A. J., Kemp, S., Benito-León, J. & Reuber, M. The influence of cognitive impairment on health-related quality of life in neurological disease. Acta Neuropsychiatrica 22, 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-5215.2009.00439.x (2010).

Li, X. et al. Prevalence of and potential risk factors for mild cognitive impairment in community-dwelling residents of Beijing. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 61, 2111–2119. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12552 (2013).

Tisato, V. et al. Gene-gene interactions among coding genes of iron-homeostasis proteins and APOE-alleles in cognitive impairment diseases. Plos One 13, e193867. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193867 (2018).

Chen, R. Association of environmental tobacco smoke with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease among never smokers. Alzheimers Dement. 8, 590–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.09.231 (2012).

Tworoger, S. S., Lee, S., Schernhammer, E. S. & Grodstein, F. The association of self-Reported sleep duration, difficulty sleeping, and snoring with cognitive function in older women. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 20, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.wad.0000201850.52707.80 (2006).

Lo, J. C., Loh, K. K., Zheng, H., Sim, S. K. & Chee, M. W. Sleep duration and age-related changes in brain structure and cognitive performance. Sleep 37, 1171–1178. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.3832 (2014).

Li, T. Z. et al. The brain structure and genetic mechanisms underlying the nonlinear association between sleep duration, cognition and mental health. Nat. Aging 2, 425–437. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-022-00210-2 (2022).

Wu, L., Sun, D. & Tan, Y. A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of sleep duration and the occurrence of cognitive disorders. Sleep Breath 22, 805–814. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-017-1527-0 (2018).

Xu, L. et al. Short or long sleep duration is associated with memory impairment in older Chinese: The Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study. Sleep 34, 575–580. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/34.5.575 (2010).

Yu, J. et al. Sleep correlates of depression and anxiety in an elderly Asian population. Psychogeriatrics 16, 191–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12138 (2016).

Furihata, R. et al. Association of short sleep duration and short time in bed with depression: A Japanese general population survey. Sleep Biol. Rhythms 13, 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/sbr.12096 (2015).

Zhai, L., Zhang, H. & Zhang, D. Sleep duration and depression among adults: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Depress. Anxiety 32, 664–670. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22386 (2015).

van Mill, J. G., Hoogendijk, W. J., Vogelzangs, N., van Dyck, R. & Penninx, B. W. Insomnia and sleep duration in a large cohort of patients with major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry 71, 239–246. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.09m05218gry (2010).

Gale, C. R., Allerhand, M., Deary, I. J., HALCyon Study Team. Is there a bidirectional relationship between depressive symptoms and cognitive ability in older people? A prospective study using the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Psychol. Med. 42, 2057–2069. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712000402 (2012).

Singh-Manoux, A. et al. Persistent depressive symptoms and cognitive function in late midlife: The Whitehall II study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 71, 1379–1385. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.09m05349gry (2010).

Wilson, R. S. et al. Depressive symptoms, cognitive decline, and risk of AD in older persons. Neurology 59, 364–370. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.59.3.364 (2002).

Zhi, T. F. et al. Associations of sleep duration and sleep quality with life satisfaction in elderly Chinese: The mediating role of depression. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 65, 211–217 (2016).

Li, J. et al. Afternoon napping and cognition in chinese older adults: Findings from the China health and retirement longitudinal study baseline assessment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 65, 373–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14368 (2017).

Lei, X., Smith, J. P., Sun, X. & Zhao, Y. Gender differences in cognition in China and reasons for change over time: Evidence from CHARLS. J. Econ. Ageing 4, 46–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeoa.2013.11.001 (2014).

Bai, A. Y., Tao, L. Y., Huang, J., Tao, J. & Liu, J. Effects of physical activity on cognitive function among patients with diabetes in China: A nationally longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 21, 481. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10537-x (2021).

Huang, W. & Zhou, Y. Effects of education on cognition at older ages: Evidence from China’s great famine. Soc. Sci. Med. 98, 54–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.02 (2013).

Andresen, E. M., Malmgren, J. A., Carter, W. B. & Patrick, D. L. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am. J. Prev. Med. 10, 77–84 (1994).

Boey, K. W. Cross-validation of a short form of the CES-D in Chinese elderly. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 14, 608–617. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199908)14:8%3c608::aid-gps991%3e3.0.co;2-z (1999).

Cheng, H. G., Chen, S., McBride, O. & Phillips, M. R. Prospective relationship of depressive symptoms, drinking, and tobacco smoking among middle-aged and elderly community-dwelling adults: Results from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). J. Affect. Disord. 195, 136–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.023 (2016).

Cole, J. C., Rabin, A. S., Smith, T. L. & Kaufman, A. S. Development and validation of a Rasch-derived CES-D short form. Psychol. Assess. 16, 360–372. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.16.4.360 (2004).

Lewinsohn, P. M., Seeley, J. R., Roberts, R. E. & Allen, N. B. Center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol. Aging 12, 277–287. https://doi.org/10.1037//0882-7974.12.2.277 (1997).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. J. Educ. Meas. 51, 335–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/jedm.12050 (2013).

MacKinnon, D. P., Fritz, M. S., Williams, J. & Lockwood, C. M. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 384–389. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03193007 (2007).

Devore, E. E. et al. Sleep duration in midlife and later life in relation to cognition. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 62, 1073–1081. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12790 (2014).

Fan, T. T. et al. Objective sleep duration is associated with cognitive deficits in primary insomnia: BDNF may play a role. Sleep https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsy192 (2019).

Spira, A. P. et al. Self-reported sleep and β-Amyloid deposition in community-dwelling older adults. JAMA Neurol. 70, 1537–1543. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.4258 (2013).

Malek-Ahmadi, M. et al. Longer self-reported sleep duration is associated with decreased performance on the montreal cognitive assessment in older adults. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 28, 333–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-015-0388-2 (2016).

van Oostrom, S. H., Nooyens, A. C. J., van Boxtel, M. P. J. & Verschuren, W. M. M. Long sleep duration is associated with lower cognitive function among middle-aged adults-the Doetinchem Cohort Study. Sleep Med. 41, 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2017.07.029 (2018).

Blackwell, T. et al. Association of sleep characteristics and cognition in older community-dwelling men: The MrOS sleep study. Sleep 34, 1347–1356. https://doi.org/10.5665/SLEEP.1276 (2011).

Sun, Y., Ma, W. R., Wu, Y. X., Koenig, H. G. & Wang, Z. Z. The mediating effect of depression in religiosity and cognitive function among Chinese muslim elderly. Neuropsychiatry 8, 1046–1053 (2018).

Dørheim, S. K., Bondevik, G. T., Eberhard-Gran, M. & Bjorvatn, B. Sleep and depression in postpartum women: A population-based study. Sleep 32, 847–855. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/32.7.847 (2009).

Zhang, X. F. et al. Relationship between sleep duration and depressive symptoms in middle-aged and elderly people in four provinces of China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 42, 1955–1961. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20200930-01210 (2021).

Mohan, D., Iype, T., Varghese, S., Usha, A. & Mohan, M. A cross-sectional study to assess prevalence and factors associated with mild cognitive impairment among older adults in an urban area of Kerala, South India. BMJ Open 9, e025473. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025473 (2019).

Fujise, N. & Ikeda, M. The relationship between depression and dementia in elderly. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi 114, 276–282 (2012).

Kim, Y. R. & Jung, H. Y. Depression and cognitive impairment in the elderly. J. Korean Geriatr. Psychiatry 11, 20–24 (2007).

Nes, R. B. et al. Major depression and life satisfaction: A population-based twin study. J. Affect. Disord. 144, 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.060 (2013).

Otenstein, L. S. et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 316, 2214–2236. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.17324 (2016).

Cao, P. Y., Luo, H. Q., Hou, L. S., Yang, X. X. & Ren, X. H. Depressive symptoms in the mid- and old-aged people in China. Sichuan Da Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 47, 763–767 (2016).

Wang, J., Zhou, Y., Liang, Y. & Liu, Z. A large sample survey of tibetan people on the Qinghai-Tibet plateau: Current situation of depression and risk factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17, 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010289 (2019).

Jackowska, M. et al. Short sleep duration is associated with shorter telomere length in healthy men: Findings from the Whitehall II cohort study. PLoS One 7, e47292. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0047292 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the China Center for Economic Research at Beijing University for providing us with the data, and we thank the CHARLS research and field team for collecting the data.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Research and Development Plan of Ningxia autonomous region (2017BY084); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 81860599).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.W.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft. S.H.: Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing. N.Y.: Data curation. R.P.: Data curation. Y.N.: Supervision, Writing—review & editing. J.L.: Methodology, Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., He, S., Yan, N. et al. Mediating role of depressive symptoms on the relationship between sleep duration and cognitive function. Sci Rep 13, 4067 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31357-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31357-6

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.