Abstract

Although several studies have been conducted in Bangladesh regarding sleep problems during the COVID-19 pandemic, none have utilized a large nationwide sample or presented their findings based on nationwide geographical distribution. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to explore the total sleep duration, night-time sleep, and daily naptime and their associated factors as well as geographic information system (GIS) distribution. A cross-sectional survey was carried out among 9730 people in April 2020, including questions relating to socio-demographic variables, behavioral and health factors, lockdown, depression, suicidal ideation, night sleep duration, and naptime duration. Descriptive and inferential statistics, both linear and multivariate regression, and spatial distribution were performed using Microsoft Excel, SPSS, Stata, and ArcGIS software. The results indicated that 64.7% reported sleeping 7–9 h a night, while 29.6% slept less than 7 h nightly, and 5.7% slept more than 9 h nightly. 43.7% reported 30–60 min of daily nap duration, whereas 20.9% napped for more than 1 h daily. Significant predictors of total daily sleep duration were being aged 18–25 years, being unemployed, being married, self-isolating 4 days or more, economic hardship, and depression. For nap duration, being aged 18–25 years, retired, a smoker, and a social media user were at relatively higher risk. The GIS distribution showed that regional division areas with high COVID-19 exposure had higher rates of non-normal sleep duration. Sleep duration showed a regional heterogeneity across the regional divisions of the country that exhibited significant associations with a multitude of socioeconomic and health factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (2019-nCoV or COVID-19) emerged in December 2019 and this unexpected and life threatening event has disrupted individuals’ way of life and confined many to living from home. Individuals still do not know how long the pandemic will last, and it has become an unprecedentedly stressful situation1,2. Due to the pandemic, psycho-emotional problems have been observed worldwide. For instance, mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic symptoms, sleep problems, and adjustment disorders have been reported globally among various age groups3,4. The pandemic led many governments to implement non-pharmaceutical measures to minimize the spread of the disease, such as spatial distancing, quarantining, and self-isolation. Such measures can exacerbate individuals’ vulnerability to loneliness, which may also increase mental health burdens and associated problems4. Other consequences related to the pandemic, such as economic distress, financial hardship, and poverty, can also increase the risk of mental health issues5,6. Mental health problems are frequently associated with insomnia and sleep duration, and sleep has a bidirectional relationship with the body's physiological system and psychological well-being7,8,9,10,11.

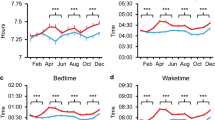

A previous study conducted among adults with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) from the USA reported that sleep duration was associated with telomere length. This study concluded that a minimum of seven hours of nightly sleep may prevent telomere damage or repair them on a nightly basis12. Narcolepsy-like sleep problems were also reported after the H1N1 influenza pandemic13. In addition, traumatic life events such as wildfires may also exacerbate sleep problems14. Similarly, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, changes in sleep duration have been reported in a large number of studies. This is not surprising given the fact that sleep problems will increase in response to natural or manmade stressful events15. Sleep problems during the COVID-19 pandemic were observed to be high in recent meta-analyses16,17. A global study recruiting participants from 49 countries indicated a significant escalation in sleep problems. During the pandemic, the average sleep duration per night also increased compared to before the pandemic (that is, 7.2 ± 1.6 h in COVID-19, 6.9 ± 1.1 h before COVID-19)18. Likewise, a couple of studies reported worsening sleep quality during the lockdown period18,19,20. Additionally, shifting in bedtime and waking time, reduction in the number of hours of sleep at night-time, and increasing daytime naps have become more prevalent than before the lockdown period19. A study among fitness coaches found that home confinement negatively affected objective measurements of sleep parameters such as sleep latency and total sleep duration, as well as deep and light sleep times21. In addition, a decrease from 61 to 48% in good sleep was estimated during home confinement22, and such sleep alterations were associated with mental health problems23.

The home confinement situation can lead an individual to use social media more frequently and intensify the risk of overusing electronic devices24. It has been found that sleep disturbances have been more common among excessive smartphone users25. Moreover, individuals' poor health conditions can also increase the risk of sleep disturbance26. Several studies during the pandemic have examined insomnia and sleep disturbances in Bangladesh, but none of them investigated sleep duration and its associated factors utilizing large samples27,28,29. Furthermore, geographical differences in terms of sleep duration were absent in these studies. It is worth mentioning that before the COVID-19 pandemic, total sleep time among Bangladeshi people had been investigated by Yunus et al.30. It was reported that 87.4% of those aged 18–64 years reported that their sleep time was 7–9 h nightly, 8.9% less than 7 h, and 3.7% more than 9 h. Therefore, the present study investigated the total sleep duration, night-time sleep, and daily naptime and its associated factors among Bangladeshi residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study also investigated division-wise sleep duration heterogeneity based on geographic information system (GIS) distribution.

Methods

Study procedure, participants, and ethics

This cross-sectional study was conducted during the first phase of the COVID-19-related lockdown in April, 2020 among 9730 people, and data were collected nationwide via online participation. Participants were recruited if they were currently residing in Bangladesh and were aged 18–64 years. Approximately 250 research assistants from all 64 districts of the country circulated online survey forms to ensure a country-wide sample of participants. This study used a non-probability convenience sampling approach. The study followed the standards of ethical practice in the Helsinki Declaration, 1975. In addition, formal IRB approval was obtained before study implementation from the Institute of Allergy and Clinical Immunology of Bangladesh [IRBIACIB/CEC/03202005], and the Jahangirnagar University ethics boards [BBEC, JU/M 2O20/COVlD-l9/(9)2]. An online consent form was provided to the participants. They were informed about the ethical issues, study aims, their non-beneficiary involvement, and right of withdrawal.

Measures

Sociodemographic information

Socio-demographic information such as participants' age, gender, occupation (i.e., employed, student, retired, housewife, unemployed, others), residence (i.e., village, Upazila town, district level town, divisional city), marital status (single, married, divorced/widowed, other) was collected. Additionally, if someone came home from a COVID-19 affected country, it was also recorded.

Behavior and health-related information

Behavior-related and health-related information was collected based on binary response (yes/no) concerning cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, presence of chronic disease, and frequency of social media use. In addition, the participants provided information on self-rated current health conditions (i.e., good, fair, poor).

Lockdown-related financial information

The impact of lockdown on finances was assessed. For instance, participants were asked if they (1) felt isolated, (2) had face-to-face contact with another person for at least 15 min, (3) been outside for 15 min daily, (4) had enough food if the lockdown lasted for more than 1 month, (5) would face economic hardship, and (6) would panic about probable economic recession. The first three items were categorized as not a single day, less than four days, and four days or more. The rest of the items were categorized as agree, disagree, and undecided.

Depressive symptoms

Participants’ depression was assessed using the nine-item Bangla version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)31, where items were recorded on a four-point scale (0 = not at all, to 3 = nearly every day) with scores ranging from 0 to 27. A score of 10 was used as the cutoff score to indicate depression32,33. Cronbach's alpha was 0.83 in the present study.

Suicidal ideation

Suicidal ideation was assessed by asking the question (answered yes/no) “Do you think about committing suicide, and are these thoughts persistent and related to COVID-19 issues?” (consistent with previous studies34,35.

Night sleep duration

Nightly sleep duration was assessed based on three categories. These were (1) recommended sleep duration = 7–9 h36, (2) longer sleep duration = more than 9 h, and (3) shorter sleep duration = less than 7 h. Longer and shorter sleep duration was categorized following a previous study conducted in the country30.

Naptime duration

Information related to daily nap time was also assessed. Participants' naptime duration was categorized as no naptime, less than 30 min, 30–60 min, and more than an hour.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using commercially available statistical software (SPSS 25.0), Stata 16 for descriptive statistics and logistic models, and ArcGIS 10.7 software for spatial analysis of COVID-19 cases and sleep patterns. First-order analyses such as independent t-tests, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and chi-square tests were performed to examine the relationship between study variables and dependent variables (total daily sleep time in 24 h, naptime, and nightly sleep duration) using Bonferroni correction (p = 0.002). Here, total daily sleep time was generated, adding both naptime and nightly sleep duration. Later, the significant variables were included for regression analysis. Normality and multicollinearity of the data were also checked for conducting regression analysis. Statistical significance at p < 0.05 with a 95% confidence interval was applied in the present study. The GIS mapping was performed using the ArcGIS 10.7 software which explored spatial distribution of sleep patterns. The collected geographic locational data of each respondent/sample was synchronised by district scale and distributed in map in terms of napping, night sleep duration, total sleep duration, night sleep duration, and number of COVID-19 cases.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Of the 9730 participants, 56.0% were male (n = 5452), 43.80% were female (n = 4263), and 0.2% participants were transgender (n = 15). The median age of the participants was 24 years (age range = 18–64 years). The most represented age range was 18–25 years (63.40%). Most of the participants (n = 5674) were students (58.3%), and employees constituted the second-largest group (26.1%). For residential status, 40.50% lived in a divisional city (n = 3941), 23.20% lived in a district-level town (n = 2253), 22.90% lived in a village (n = 2243), and the remainder lived in an Upazila [sub-district] setting (Table 1).

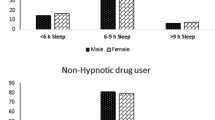

Prevalence of sleep duration

Just over two-fifths of participants (43.7%) reported having a nap duration of 30–60 min daily (n = 4256), whereas 20.9% had a nap duration of more than an hour daily (n = 2034), 3.0% had a nap duration of fewer than 30 min (n = 289), and 2.40% had no daily nap at all (n = 3151). In addition, most of the participants (n = 6296, 64.7%) were sleeping 7–9 h nightly, whereas 29.6% slept less than 7 h nightly (n = 2882) and 5.7% slept more than 9 h nightly (n = 552).

Association between study variables and total daily sleep duration

The total daily sleep time of the participants was presented as mean score and standard deviation in Table 1. Participants aged 18–25 years showed significantly higher mean scores than any other age group (F = 64.346, p < 0.001). Females, those unemployed, and those who were single had significantly higher mean scores in terms of total daily sleep time (p < 0.001). Social media users were more prone to having an increase in total daily sleep than non-users (t = 5.264, p < 0.001). In addition, participants who were socially isolated for four days or more, had no face-to-face contact at all with anyone for 15 min or more, and those facing economic hardship had an increased total daily mean sleep time (p < 0.001). Furthermore, those having depressive symptoms (t = 4.002, p < 0.001), and those experiencing suicidal ideation (t = 3.309, p < 0.001) had a greater mean score than those who did not in terms of total daily sleep time.

Association between study variables and daily naptime

Participants' daily naptime association with the study variables is shown in Table 2. The age group had a significant relationship with naptime, with those aged 18–25 years reporting significantly more naptime than other age groups (χ2 = 323.736, p < 0.001). Gender had a statistically significant association with naptime with males reporting more naptime than females and transgender individuals (χ2 = 61.152, p < 0.001). Students reported significantly more naptime than others occupations (χ2 = 422.597, p < 0.001). Naptime duration was also significantly higher among single participants than other relationship status groups (χ2 = 223.616, p < 0.001). In addition, non-smokers, non-alcohol consumers, and social media users all reported more naptime than their non-user counterparts (p < 0.001). Participants not having face-to-face contact with another person for 15 min or more in a single day, not being outside for more than 15 min in a single day, running out of food, and economic recession was also found to have a significant relationship with naptime (p < 0.001). Furthermore, participants who were non-depressed (χ2 = 15.898, p = 0.001), not suffering from a chronic medical condition (χ2 = 22.038, p < 0.001), and not having suicidal ideation (χ2 = 18.350, p < 0.001) all had significantly more naptime than their counterparts.

Association between study variables and nightly sleep duration

The associations between nightly sleep duration and the study variables are presented in Table 3. No significant association was observed between gender and nightly sleep duration. Non-smokers (χ2 = 43.558, p < 0.001) and those self-isolating for four days or more (χ2 = 16.503, p = 0.002) reported significantly more nightly sleep than their counterparts. In addition, not suffering from depressive symptoms (χ2 = 15.606, p < 0.001), and not having suicidal ideation (χ2 = 12.134, p = 0.002) reported significantly higher nightly sleep duration than their counterparts.

Linear regression between selected variables and total daily sleep duration

Table 4 presents the linear regression between selected variables and total daily sleep duration. Results showed that participants who were aged 18–25 years (coefficient = 19.97, p < 0.001), aged 26–35 years (coefficient = 10.45, p = 0.014), unemployed (coefficient = 20.66, p = 0.004), married (coefficient = 11.22, p < 0.001), self-isolated 4 days or more (coefficient = 9.08, p = 0.028), had face-to-face contact with another person for 15 min or more for four days or more weekly (coefficient = 7.79, p = 0.024), assumed they would face economic hardship (coefficient = 7.51, p = 0.008), and had depressive symptoms (coefficient = 4.76, p = 0.031) were significant predictors of total daily sleep time. The model explained a 2.46% variance to predict total daily sleep duration (p < 0.001).

Multinomial logistic regression between selected variables and nap duration

Table 5 presents a multinominal logistic regression between selected variables and naptime. Participants aged 18–25 years, and 26–35 years were 1.87 (CI: 1.31–2.66) and 1.45 (CI: 1.07–1.97) times higher risk of taking more than an hour’s nap daily compared to those aged more than 35 years. Retired individuals were more likely to take more than an hour's nap daily than other professionals (RRR: 3.72, CI: 1.51–9.14). In addition, smokers were less likely to take naps compared to those who were not (RRR: 0.55, CI: 0.36–0.85 for less than 30 min; RRR: 0.65, CI: 0.56–0.75 for 30 to 60 min; RRR: 0.65, CI: 0.54–0.78 for more than 60 min). Social media users were 5.71 times (CI: 2.76–11.81), 1.55 times (CI: 1.26–1.90), and 2.15 times (CI: 1.56–2.98) higher risk of taking a nap less than 30 min daily, 30–60 min daily, and more than an hour daily respectively compared to non-users. Moreover, participants who did not think they would have enough food to get through the pandemic were at higher risk of taking a nap 30–60 min daily than those who did (RRR: 1.12, CI: 1.01–1.25).

Multinomial logistic regression between selected variables and nightly sleep duration

Table 6 presents a multinominal regression between selected variables and nightly sleep duration. It showed that those aged 26–35 years were at lower risk of sleeping less than 7 h nightly than those aged over 35 years (RRR: 0.80, CI: 0.67–0.94) and that those aged 18–25 years were at higher risk of sleeping more than 9 h nightly (RRR: 1.65, CI: 1.06–2.58) compared to aged more than 35 years. Housewives were at a lower risk of sleeping less than 7 h nightly than other occupations (RRR: 0.74, CI: 0.56–0.98). Additionally, cigarette smokers were more likely to sleep more than 9 h nightly compared to non-smokers (RRR: 1.44, CI: 1.15–2.48). Participants self-isolating for four days or more were more likely to sleep more than 9 h nightly compared to those who were not isolated on any day (RRR: 1.66, CI: 1.11–2.48). Furthermore, individuals with depressive symptoms were at 1.28 times higher risk of sleeping more than 9 h nightly than those with no depressive symptoms. Those experiencing suicidal ideation also had increased duration of sleep nightly than those not experiencing suicidal ideation (RRR: 1.46, CI: 1.05–2.05).

Sleep duration during the COVID-19 pandemic by regional divisions

Results of the regional division-wise sleep duration during the COVID-19 pandemic are presented in Fig. 1. More specifically, nightly sleep duration, daily nap duration, and total daily sleep are displayed across regional divisions. Nap duration was significantly associated with respective regional divisions (χ2 = 51.438, p < 0.001), whereas night sleep duration, and total sleep duration were not significant (p = 0.55 and p = 0.58 respectively). Spatial distribution suggested that 24% of participants from the Barisal had a nap duration of more than 1 h followed by Mymensingh (22.30%) and Dhaka (21.40%). A nap duration between 30 and 60 min daily was highest in Sylhet (50.20%), followed by Khulna (49.80%) and Mymensingh (47%). For nightly sleep duration, 67.60% of participants from Rangpur reported 7–9 h, whereas less than 7 h was the highest among the residents of Dhaka. About 7% of residents from Barisal had a night sleep duration of more than 9 h. The mean score for total sleep duration in 24 h was highest among residents from Barisal, while the lowest was found among residents in Rajshahi. It was also found that the participants from regional divisions with higher COVID-19 cases (for example, Dhaka) were more likely to have abnormal sleep status.

Discussion

The implementation of public health prevention measures such as spatial distancing, self-isolating, and quarantining during the COVID-19 pandemic were introduced to minimize virus transmission until vaccines were introduced. However, such restrictive measures may also increase mental health problems among individuals 3. Studies throughout the world have reported higher levels of mental health problems and sleep problems during the pandemic16,37. Although a few studies examining COVID-19-related sleep problems have been conducted previously in Bangladesh, none of them established the total sleep duration, night-time sleep, and daily naptime and its associated factors among the Bangladeshi residents during the COVID-19 pandemic alongside GIS-based distributions.

The present study found that 64.7% of participants slept 7–9 h nightly, while 29.6% slept less than 7 h nightly and 5.7% slept more than 9 h nightly. Before the pandemic, a study from Bangladesh30 comprising 3968 participants from rural and urban areas observed total daily sleep time. They reported that 87.4% of adults (aged 18–64 years) slept between 7 and 9 h nightly, whereas 8.9% slept less than 7 h nightly and 3.7% slept more than 9 h nightly. In the same study, 41.9%, 55.6%, and 2.5% of school-aged children (aged 6–13 years) slept between 9 and 11 h, less than 9 h, and more than 11 h, respectively. Using 8–10 h as recommended nightly sleep time, the prevalence rate was 76.1% for teenagers and 56.4% among older adults with a recommended 7–8 h of nightly sleep time30. A previous multi-country study18 demonstrated a higher prevalence of sleeping less than 7 h nightly during the pandemic (i.e., 35%), whereas the same study noted the rate was 42% before the pandemic. They also reported that more than one-third of the participants reported worsening sleep during the pandemic18. Another study conducted among 782 COVID-19 affected community participants in India reported increased sleep duration (before infection: 7.84 ± 1.33 h; after infection: 8.15 ± 2.00 h)38. Shorter sleep duration is significantly associated with obesity and diabetes39, increased BMI40, and telomere damage12, whereas longer sleep duration can lead to a better health-related quality of life41.

Daily nap duration was reported to be 30–60 min among 43.7% of participants, 20.9% more than 60 min, 3.0% less than 30 min, and 2.40% had no nap at all. A slightly higher nap duration was reported from a neighboring country (India) which reported that 25% of participants napped more than 60 min daily. The study also found a significant differences before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of reporting changes in sleep schedule (31.1% vs. 38% for < 60 min, 9.2% vs. 25% for > 60 min, 59.7% vs. 37% for no naps; all p-values < 0.001)19. Another study among COVID-19 infected community participants reported that 11.1% took naps less than 30 min, 12.4% took naps of 30–45 min, 10.4% took naps lasting more than 45 min, 14.8% took naps once in a while, and 20.3% took naps during holidays or weekends before getting infected with COVID-1938. However, changes in nap pattern were observed after being infected with COVID-19 because 20.2% had longer nap duration compared to their previous nap time38.

The present study identified several factors associated with sleep duration such as participants being aged 18–25 years, being unemployed, being married, being self-isolated for four days or more week, being a cigarette smoker, being a social media user, facing economic hardship, having depressive symptoms, and experiencing suicidal ideation. The sleep patterns of young adults changed during the COVID-19 pandemic. The youngest age group (18–24 years old) had the shortest sleep duration before lockdown but this group reported delayed wake-up times and longer sleep duration during the lockdown period compared with other age groups42. Similar findings have also been observed in a different study in Bangladesh before the pandemic30. Additionally, being married and unemployed was associated with increased sleep time. The previous Bangladeshi study also reported that total sleep time had a significant relationship with marital status and unemployment30.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a significant change has been observed in terms of sleep problems19,43. Suffering from mental health problems such as depression has had a strong association with sleep difficulties19,43, which is consistent with the present study’s results. However, a recent meta-analysis by Zhai et al.44 found that both short sleep duration and long sleep duration were significantly associated with increased risk of depression among adults. The study reported that the pooled relative risk for depression was 1.31 (95% CI: 1.04–1.64), and 1.42 (95% CI: 1.04–1.92) in terms of short and long sleep duration, respectively44. The present study reported that participants having depressive symptoms were more likely to have a longer sleep duration (more than 9 h nightly). Similarly, findings from meta-analysis supported that longer sleep duration had a significant association with increased risk of depression44. Conversely, the present study’s results differed from other studies reporting short sleep duration as an independent risk factor for depression45,46. Therefore, to identify the actual relationship between sleep duration and depressive symptoms, further investigation is required.

In addition, using social media more frequently could potentially affect the sleep cycle. A previous study demonstrated that using social media late at night and high emotional attachment to smartphones was associated with poor sleep quality47. Blue light emission produced by smartphones possibly decreases melatonin production and affects circadian rhythms adversely48. Additionally, the relationship between social media use and cognitive function depletion during the day was also reported in another study and associated with higher daytime naps25.

With respect to GIS-based spatial distribution, nap duration was significantly associated with the respective regional divisions. Findings suggested that participants from Barisal had a nap duration of more than 1 h, whereas, 30–60 min nap duration was highest among the participants from Sylhet. For nightly sleep duration, those in Rangpur and Sylhet had higher normal sleep status (7–9 h), whereas Dhaka had the lowest prevalence of normal sleep status. The number of COVID-19 cases in Dhaka, the capital of the country, was the highest at the time of the survey. It is likely that some individuals panicked and feared being infected with COVID-19 resulting in a change in their normal sleep status. The fear of COVID-19 increases among those who are in high-exposure professions such as healthcare professionals49, and this cohort has been reported as being one of the most vulnerable to mental health suffering as reported in a recent meta-analysis50. Other studies have reported that COVID-19 exposure increases psychological instabilities, whereas fear of COVID-19 partially mediates the association between COVID-19 exposure and depression. Therefore, it is not surprising that abnormal sleep status was associated with high COVID-19 exposure regions compared to other regions with lower COVID-19 exposure (for example, Rangpur, Sylhet).

In addition to the level of COVID-19 exposure, the findings may be explained by the number of people living in a city. For instance, a previous Bangladeshi study found that individuals living in a large city (e.g., Dhaka) had less sleep30. Dhaka, the largest city in Bangladesh (and one of the most densely populated and unplanned cities worldwide), is in a poor situation with respect to environmental indicators leading to the alteration of normal sleep time. For instance, air pollution concentration has been negatively associated with sleep duration. More specifically, one standard deviation increase in air pollution concentration was reported to be associated with a reduction in total daily hours of sleep by 0.6851. As aforementioned, Dhaka is one of the most populated cities worldwide and is the third most air-polluted city worldwide52, and it is not unusual to have altered sleep status among this population. The environmental conditions for the cities of Rangpur, Sylhet and Chittagong, are better with less exposure to air pollution which may also be another explanation for the higher rates of normal sleep status in these cities.

Implications of the findings

The present study included a large sample size as well as individuals from every regional division in the country, both of which may potentially increase the generalizability of the findings. For the first time, a regional distribution was provided in terms of sleep duration during the pandemic that may be used to identify in which regions people are more susceptible to abnormal sleep duration. The geolocated findings can therefore facilitate longitudinal studies by enabling recruitment of susceptible individuals from a particular geographical area to assess the long-term effects of abnormal sleep on their quality of life.

Limitations

The present study has some limitations. The study was cross-sectional. Therefore, it cannot provide any determination of causality between the variables. The study was carried out utilizing online platforms due to the restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which limited face-to-face interaction. Consequently, more than half of the participants belonged to the student cohort due to their availability online, indicating that the sample was not nationally representative. Moreover, the present study did not consider other important predictors of sleep disturbances, such as the (1) history of sleep problems before the COVID-19 pandemic, (2) use of specific sleep medications, (3) late-night activities and habits, and (4) engagement with smartphones. There may also be a selection bias because the data were collected using an online platform, and the sample was self-selecting.

Conclusions

This study is the first to provide sleep time mapping in Bangladesh. The present study concluded that during the COVID-19 pandemic more people had abnormal sleep duration compared to before the pandemic in Bangladesh (i.e., 29.6% vs 8.9% slept less than 7 h nightly; and 5.7% vs 3.7% slept more than 9 h nightly). In addition, a number of associated factors of abnormal sleep status were identified (e.g., age, unemployment, marital status, cigarette smoking, depression, suicidal ideation etc.), and individuals living in areas of high COVID-19 exposure areas reported higher levels of sleep abnormality. These findings are helpful for the respective regional divisional authorities undertaking any mental health interventions aimed at prevention and management strategies to support vulnerable regions and sectors of the population.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Altena, E. et al. Dealing with sleep problems during home confinement due to the COVID-19 outbreak: Practical recommendations from a task force of the European CBT-I Academy. J. Sleep Res. Adv. Online Publ. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13052 (2020).

Mamun, M. A. & Griffiths, M. D. First COVID-19 suicide case in Bangladesh due to fear of COVID-19 and xenophobia: Possible suicide prevention strategies. Asian J. Psychiatr. 51, 102073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102073 (2020).

Khan, K. S., Mamun, M. A., Griffiths, M. D. & Ullah, I. The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic across different cohorts. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00367-0 (2020).

Hossain, M. M. et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in South Asia during COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06677 (2020).

Lin, C.-Y. Social reaction toward the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Soc. Heal. Behav. 3, 1. https://doi.org/10.4103/SHB.SHB_11_20 (2020).

Mamun, M. A. & Ullah, I. COVID-19 suicides in Pakistan, dying off not COVID-19 fear but poverty? The forthcoming economic challenges for a developing country. Brain. Behav. Immun. 87, 163–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.028 (2020).

Alimoradi, Z. et al. Internet addiction and sleep problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 47, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2019.06.004 (2019).

Lin, C. Y. et al. Temporal associations between morningness/eveningness, problematic social media use, psychological distress and daytime sleepiness: Mediated roles of sleep quality and insomnia among young adults. J. Sleep Res. 30, e13076. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13076 (2021).

Pakpour, A. H., Griffiths, M. D., Ohayon, M. M., Broström, A. & Lin, C.-Y. A good night sleep-The role of psychosocial factors across life. Front. Neurosci. 14, 520. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.00520 (2020).

Manzar, M. D., Zannat, W. & Hussain, M. E. Sleep and physiological systems: A functional perspective. Biol. Rhythm Res. 46, 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/09291016.2014.966504 (2015).

Manzar, M. D. et al. Prevalence of poor sleep quality in the Ethiopian population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Breathing 24, 709–716. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-019-01871-x (2020).

Lee, K. A. et al. Telomere length is associated with sleep duration but not sleep quality in adults with Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Sleep 37, 157–166. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.3328 (2014).

Sarkanen, T. O., Alakuijala, A. P. E., Dauvilliers, Y. A. & Partinen, M. M. Incidence of narcolepsy after H1N1 influenza and vaccinations: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 38, 177–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2017.06.006 (2018).

Belleville, G., Ouellet, M.-C. & Morin, C. M. Post-traumatic stress among evacuees from the 2016 Fort McMurray Wildfires: Exploration of psychological and sleep symptoms three months after the evacuation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 1604. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16091604 (2019).

Morin, C. M. & Carrier, J. The acute effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on insomnia and psychological symptoms. Sleep Med. 77, 346–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.06.005 (2021).

Haitham, J. et al. Sleep problems during the COVID-19 pandemic by population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 17, 299–313. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8930 (2021).

Alimoradi, Z. et al. Gender-specific estimates of sleep problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sleep Res. 31, e13432–e13432. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13432 (2021).

Mandelkorn, U. et al. Escalation of sleep disturbances amid the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional international study. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 17, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.5664/JCSM.8800 (2021).

Gupta, R. et al. Changes in sleep pattern and sleep quality during COVID-19 lockdown. Indian J. Psychiatry 62, 370. https://doi.org/10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_523_20 (2020).

Akbari, H. A. et al. How physical activity behavior affected well-being, anxiety and sleep quality during COVID-19 restrictions in Iran. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 25, 7847–7857. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202112_27632 (2021).

Dergaa, I. et al. COVID-19 lockdown: Impairments of objective measurements of selected physical activity, cardiorespiratory and sleep parameters in trained fitness coaches. EXCLI J. 21, 1084–1098. https://doi.org/10.17179/excli2022-4986 (2022).

Trabelsi, K. et al. Globally altered sleep patterns and physical activity levels by confinement in 5056 individuals: ECLB COVID-19 international online survey. Biol. Sport 38, 495–506. https://doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2021.101605 (2021).

Trabelsi, K. et al. Sleep quality and physical activity as predictors of mental wellbeing variance in older adults during COVID-19 lockdown: ECLB COVID-19 international online survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084329 (2021).

Hossain, M. T. et al. Social and electronic media exposure and generalized anxiety disorder among people during COVID-19 outbreak in Bangladesh: A preliminary observation. PLoS ONE 15, e0238974. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238974 (2020).

Luqman, A., Masood, A., Shahzad, F., Shahbaz, M. & Feng, Y. Untangling the adverse effects of late-night usage of smartphone-based SNS among University students. Behav. Inf. Technol. 40, 1671–1687. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2020.1773538 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Sleep disturbances among Chinese residents during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 outbreak and associated factors. Sleep Med. 74, 199–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2020.1773538 (2020).

Barua, L., Zaman, M. S., Omi, F. R. & Faruque, M. Psychological burden of the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated factors among frontline doctors of Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. F1000Research 9, 1304. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.27189.3 (2020).

Ara, T., Rahman, M., Hossain, M. & Ahmed, A. Identifying the associated risk factors of sleep disturbance during the COVID-19 lockdown in Bangladesh: A web-based survey. Front. Psychiatry 11, 966. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.580268 (2020).

Ali, M. et al. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety, depression, and insomnia among healthcare workers in Dhaka city amid COVID-19 pandemic. Res. Sq. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-101990/v1 (2020).

Yunus, F. M. et al. How many hours do people sleep in Bangladesh? A country-representative survey. J. Sleep Res. 25, 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12381 (2016).

Chowdhury, A. N., Ghosh, S. & Sanyal, D. Bengali adaptation of Brief Patient Health Questionnaire for screening depression at primary care. J. Indian Med. Assoc. 102, 544–547 (2004).

Mamun, M. A., Huq, N., Papia, Z. F., Tasfina, S. & Gozal, D. Prevalence of depression among Bangladeshi village women subsequent to a natural disaster: A pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 276, 124–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.05.007 (2019).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16, 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x (2001).

Jahan, S., Araf, K., Gozal, D., Griffiths, M. D. & Mamun, M. A. Depression and suicidal behaviors among Bangladeshi mothers of children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder: A comparative study. Asian J. Psychiatr. 51, 101994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101994 (2020).

McKinnon, B., Gariépy, G., Sentenac, M. & Elgar, F. J. Comportements suicidaires des adolescents dans 32 pays à revenu faible et intermédiaire. Bull. World Health Organ. 94, 340-350F. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.15.163295 (2016).

Hirshkowitz, M. et al. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: Methodology and results summary. Sleep Heal. 1, 40–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.010 (2015).

Vindegaard, N. & Benros, M. E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav. Immun. 89, 531–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048 (2020).

John, B., Marath, U., Valappil, S. P., Mathew, D. & Renjitha, M. Sleep pattern changes and the level of fatigue reported in a community sample of adults during COVID-19 pandemic. Sleep Vigil. 6, 297–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41782-022-00210-7 (2022).

Anujuo, K. et al. Relationship between short sleep duration and cardiovascular risk factors in a multi-ethnic cohort—the helius study. Sleep Med. 16, 1482–1488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2015.08.014 (2015).

Peltzer, K. & Pengpid, S. Sleep duration, sleep quality, body mass index, and waist circumference among young adults from 24 low- and middle-income and two high-income countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14, 566. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14060566 (2017).

Albrecht, J. N. et al. Association between homeschooling and adolescent sleep duration and health during COVID-19 pandemic high school closures. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2142100. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.42100 (2022).

Sinha, M., Pande, B. & Sinha, R. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on sleep-wake schedule and associated lifestyle related behavior: A national survey. J. Public Health Res. 9, 1826. https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2020.1826 (2020).

Cellini, N., Canale, N., Mioni, G. & Costa, S. Changes in sleep pattern, sense of time and digital media use during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. J. Sleep Res. 29, e13074. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13074 (2020).

Zhai, L., Zhang, H. & Zhang, D. Sleep duration and depression among adults: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Depress. Anxiety 32, 664–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.05.008 (2015).

Gehrman, P. et al. Predeployment sleep duration and insomnia symptoms as risk factors for new-onset mental health disorders following military deployment. Sleep 36, 1009–1018. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.2798 (2013).

Li, Y. et al. Longitudinal association of sleep duration with depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older Chinese. Sci. Rep. 7, 11794. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12182-0 (2017).

Woods, H. C. & Scott, H. #Sleepyteens: Social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. J. Adolesc. 51, 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.05.008 (2016).

Christensen, M. A. et al. Direct measurements of smartphone screen-time: Relationships with demographics and sleep. PLoS ONE 11, e0165331. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165331 (2016).

Quadros, S., Garg, S., Ranjan, R., Vijayasarathi, G. & Mamun, M. A. Fear of COVID 19 infection across different cohorts: A scoping review. Front. Psychiatry 12, 1289. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.708430 (2021).

Krishnamoorthy, Y., Nagarajan, R., Saya, G. K. & Menon, V. Prevalence of psychological morbidities among general population, healthcare workers and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 293, 113382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113382 (2020).

Yu, H., Chen, P., Paige Gordon, S., Yu, M. & Wang, Y. The association between air pollution and sleep duration: A cohort study of freshmen at a university in Beijing, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 3362. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183362 (2019).

IQAir. Air Quality and Pollution City Ranking. https://www.iqair.com/world-air-quality-ranking (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants.

Funding

The present study did not receive any financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.A.-M., and M.A.M. conceived and designed the study outline. A.K.M.I.B. developed the initial questionnaire and M.A.M. finalized it. All authors then inputted and validated the study plan and survey instrument, especially A.H.P. M.A.M., N.S., A.K.M.I.B. & S.H. led the project implementation with help of F.A.-M., I.H., A.H.A., M.A.S. & I.R. The project was supervised by M.T.S., M.M., D.G., M.D.G., L.Z., D.M. & A.H.P. Data collection ad data collector team were managed by M.A.M., N.S., A.K.M.I.B., S.H., F.a.-M., I.H., A.H.A., and M.A.S. The dataset was cleaned by N.S. & F.A.-M. F.A.-M. carried out the formal statistical analyses and incorporated results with the guidance of A.H.P. and C.-Y.L., and NH performed the GIS-mapping. F.A.-M. searched the literature and wrote the first draft. The first extensive review and edits were done by D.M. & D.G. Other authors reviewed and contributed subsequently in the draft, especially M.D.G. Final approval was provided by all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Mamun, F., Hussain, N., Sakib, N. et al. Sleep duration during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: A GIS-based large sample survey study. Sci Rep 13, 3368 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30023-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30023-1

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.