Abstract

This study aimed to develop a Self-Active Aging Index (S-AAI) for the rural community of Thailand using the World Health Organization (WHO) framework, and score it according to age and gender. Overall, 1,098 elderly people were randomly selected. The self-reported questionnaires were categorized into three segments: health, participation, and security according to the WHO framework. An exploratory factor analysis was used to determine appropriate components. The S-AAI comprised 28 indicators and 9 factors: (1) mental/subjective health; (2) physical health; (3) health behavior and chronic disease; (4) vision and hearing; (5) oral health; (6) social participation; (7) stability in life; (8) financial stability; and (9) secure living. The overall S-AAI for all components was 0.65, with the index inversely proportional to age, but with no gender differences. The S-AAI is potentially Thailand's first multi-dimensional interactive aging assessment tool with a unique cultural context for rural areas. Although this tool is valid, it requires reliability testing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human life expectancy has been increasing across the globe, and it is estimated that between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the world's population aged 60 and above will nearly double, from 12 to 22%. This was initially evident in high-income countries (such as Japan), but by 2050, two-thirds of the world's population over 60 is expected to live in low- and middle-income countries, with Thailand among the middle-income countries1. Thailand has been witnessing an aging society since 2005. The proportion of elderly people accounts for 10.3% of the country's population, and it is expected that the proportion of the elderly population will continue to increase. Population projections from Thailand show that by 2022, Thailand will become a fully aged society and by 2032, it will enter a super-aged society2.

In 2002, the World Health Organization (WHO) had proposed the concept of active aging, which focuses on promoting the quality of life of the elderly in terms of abilities, values, benefits, and potential. By definition, active aging is an appropriate process that leads to good health, social participation, and security to enhance the quality of life of the elderly3. In this study, the researchers used the term “active aging” in the context of the WHO4, which has broadened the perspective on health. It is of the view that health is everyone’s responsibility, not just healthcare workers given that everyone has the potential to take care of individual health. This concept supports the process of stepping into an aging society in every country.

Several countries, including Thailand, have developed tools to assess the active aging of older adults in the past decade2,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. The development of a tool based on the Active Aging Index in accordance with the framework of the WHO focuses on three areas: health, participation, and security, with an increase in indicators according to the context of the area.

Previous studies from abroad have mostly presented national benchmarking indices; for example, the European Center Vienna developed an “Active Aging Index” to assess the active aging of older adults among the 28 European countries20. Thailand developed an active aging index using big data collected from the 2011 National Statistical Office survey, so there are limitations in some indicators that may not be covered, such as oral health and nutritional status.

In addition, past studies have found that the potential aging index varies by context, region, and gender6. Therefore, this study aimed to develop a new index of active aging that is specific to rural areas where older adults can assess themselves. Additionally, this tool was used to assess the active aging of the elderly according to gender and age group.

Methods

Data source and sample

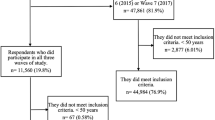

This study used data from our previous survey of 1,098 elderly people aged 60 and above from lower northern Thailand21. The sample size was sufficient for the factor analysis, according to general guidelines, under which a sample of 50 is considered as very poor, 100 as poor, 200 as fair, 300 as good, 500 as very good, and 1,000 as excellent22.

The participants were selected using multistage random sampling. The first step was clustered in nine provinces of lower northern Thailand by lottery covering five provinces: Phitsanulok, Uttaradit, Sukhothai, Kamphaeng Phet, and Tak. Second, random samples were collected to select the districts in each province. Finally, to obtain the proportion of the elderly cluster sampling in each district, we followed simple random sampling to determine the number of health-promoting hospitals (SDHPH) in each district. SDHPH electives from the family file system was used to reduce selection bias. The selection criteria were as follows: (1) being at least 60 years old, (2) living in the area for more than six months, (3) able to communicate, and (4) willingness to participate. The exclusion criterion was individuals with a history of mental disorders because they often had an increased level of perception of threat. The Institutional Review Board of Naresuan University approved this study ethically (COA No. 003/2018; IRB No. 1102/60). The study procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were informed about the study, and they signed the consent form prior to participation. Data were collected using a cross-sectional design from February to June 2019, with five public health professionals trained as research assistants, to reduce collection bias. All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Measures

The research tool for data collection was a structured interview questionnaire developed by the researchers based on the framework for the development of WHO's Active Aging Index3 and a previous study in Thailand2,6,23,24 by adjusting the indicators in all 3 components and 32 indicators, namely health, participation, and security, to match the context of the Thai rural area in the lower northern region. These indicators will be used to extract factors that include components in various aspects, as shown in Table 1. In addition, general information of the samples was collected to describe characteristics such as age, gender, religion, occupation, literacy, and number of family members, living style, and length of stay in the community. These tools were validated by three experts for content validity with Indexes of Item-Objective Congruence greater than 0.5 prior to data collection.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics, including frequency and percentage, were used to describe categorical data, whereas mean and standard deviation was used for continuous data of demographic characteristics. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to explore and group highly correlated items together to establish indicators that are key components of the policy framework for active aging by the WHO3. The EFA was run using SPSS version 17. Before conducting EFA, (1) z-scores for all items were generated because of variation between items, and (2) the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value was obtained to determine whether the sample was adequate; we also carried out Bartlett’s test of sphericity, which tests whether there is sufficient correlation between the variables and hence justifies the factor analysis. We then performed an EFA using (1) factor extraction using principal component analysis and (2) factor rotation using the Promax method. An eigenvalue greater than 1.0 is considered as a criterion to determine the number of components to be retained. S-AAI scores ranging from 0 to 1 were calculated for all participants by following the weight score for each dimension using raw scores2,8,10,24 (Supplementary Material). Descriptive statistics were calculated to obtain S-AAI scores by age and gender and the difference was tested by one-way analysis of variance and t-test for independence at the statistical level of 0.05.

Informed consent

All participants were informed about the study, and they signed the informed consent form prior to participation.

Result

Sample characteristics

The sample consisted of 1,098 individuals with an average age of 71.01 (SD 7.55 years; age range 60–95). Most participants were women (61.4%) and Buddhists (98.5%). Before the age of 60, a majority of the participants had been farmers (65.4%), but after retirement, most were not engaged (50.5%), followed by farmers (35.6%). About half of the elderly participants could read (52.4%) and write (48.3%). Housing aspect: There were between 1–13 family members (Mean = 3.54, SD = 1.76). Nearly one in ten accounted for the elderly living alone (9.2%), with the elderly living with a husband/wife and their relatives (31.0%), children (35.2%), and spouses (24.5%) in comparable proportions. Most of them were residents of the community since birth (Mean 52.27 years, SD 18.53 years).

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) results

The indicators of the 32 variables in Table 1 were analyzed to extract factors according to the WHO concept in three components (health, participation, and security). The factor structure was examined using principal component extraction with Varimax rotation (n = 1,098). The Bartlett Sphericity test (p < 0.001) and Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO = 0.729) test indicated that factor analysis seemed to be highly adjusted for this analysis. Nine factors (Table 2) explained 55.373% of the total variance. A total of 28 retained items had factor loading values greater than 0.3 (four items with factor loadings lower than 0.3 were omitted), and only one of the nine factors could be described meaningfully in terms of respective components. The nine new factors of active aging were theoretically organized and presented in a simple structure. These factors were named after the WHO framework as follows: (1) mental/subjective health, (2) physical health, (3) health behavior and chronic disease, (4) vision and hearing, (5) oral health, (6) social participation, (7) stability in life, (8) financial stability, and (9) secure living.

Self-Active Aging Index (S-AAI) results

The S-AAI scores for elderly individuals in rural Thailand for each factor is shown in Fig. 1. The mean overall S-AAI score was 0.65. Secure living (security domain) showed the highest score (0.91), followed by health: vision and hearing (0.78) and physical health (0.78). For other domains, the score was less than 0.70 (Fig. 1).

Figure 2 shows the distribution of overall S-AAI and domain scores stratified by gender. The S-AAI was 0.65 for both male and female elderly individuals. When considering each domain, it was found that elderly males scored significantly higher than females in terms of mental/subjective health, physical health, and secure living. In contrast, older women scored higher than men for health behavior, chronic disease, and stability in life. In addition, Fig. 3 shows the classification of S-AAI scores by age group, which found that the scores were statistically significantly inversely related to age, with the age group 60–69 having the highest score (0.67), followed by those aged 70–79 (0.64), and 80 and over (0.61). When considering each domain, it was found that the S-AAI scores differed statistically, with the scores decreasing with increasing age for mental/subjective health, physical health, oral health, social participation, financial stability, and secure living, while it increased with age for stability in life.

Discussion

This study aimed to develop an S-AAI for the rural elderly population in Thailand. This tool was developed based on the WHO conceptual framework (health, participation, and security) and a review of 32 indicators of active aging in Thailand. After exploratory factor analysis of the remaining 28 indicators, they were categorized into nine determinant factors that were similar to the previous study18,19 and a systematic review of the diverse and varied facets of active aging comprises 15 topics25. However, the employment component that is not included in the S-AAI differs from the international index development15. Considering the working context of Thai elderly in rural areas, most of them are farmers or have families who take care of them. This index mostly focuses on health components, comprising five factors and sixteen indicators. Personal health is an essential condition of independent living in relation to the individual, family, and social environment3.

The first major determinant of active aging is mental/subjective health, which explains the greatest variability in S-AAI. This factor includes five indicators: no happiness, psychological distress, sleep problems, forgetfulness, and subjective physical health. Physical health (Factor 2) incorporated three items: the Barthel ADL Index, functional ability, and exercise/physical activity. Two of these health factors were of prime importance, indicating that older adults living a healthy physical and mental life with a perception of their own wellness experienced more active aging. The findings are consistent with numerous studies suggesting that a healthy lifestyle is closely related to healthy aging23,26 and successful aging9. This was previously confirmed by research that psychology has no strong relevance to aging12,27. In addition, a study in Brazil indicated that self-assessed health is an important health measure28. Factor 3 (health behavior and chronic disease) is related to health behavior and consists of four indicators: smoking, alcohol drinking, BMI level, and the number of chronic diseases. This is supported by several studies that have focused on health behaviors6,18. Vision and hearing (Factor 4) consisted of two indicators: hearing and visual abilities. Both indicators are determinants of the apparent health of the elderly owing to age-related deterioration. There is also a strong correlation between hearing impairment and loneliness in older adults29. Two indicators of oral health (Factor 5) were included: having at least 20 teeth and facing problems chewing or swallowing food, which were included based on recommendations from previous studies18.

The second component is participation, which consists of one factor and two indicators. The WHO defines participation as engagement in family, community, and social activities. These activities help create a sense of belonging, dignity, and emotional attachment to the family, which improves the mental and physical health of the elderly3. Our tool focusing on social participation (Factor 6) consisted of two items: being a group member or club and participation in activities of the elderly club. Some of the indicators based on the initial conceptual framework such as marital status and meeting neighbors or relatives were excluded. Additionally, some indicators, including working and providing financial support to families, were included in the security component.

The last component is security, which consists of 3 factors and 10 indicators. In this situation, having security guarantees means physical security and economic stability, giving the elderly a good quality of life3. Stability in life (Factor7) has also been identified as an important aspect of active aging. This factor involves work, the main source of income, debt, income level, and education level. According to the initial conceptual framework, the work was organized into a component related to participation. It also represents income that leads to stability in life. The three items loaded on Factor 8 (financial stability) consisted of sufficiency of income, savings, and providing financial support to families. Several studies have indicated that financial stability is important5,6,12,18. Financial security maximizes a sense of security and independence, especially among older adults, who are mostly unemployed. The last factor in active aging, which we call “secure living” (Factor 9), consists of two items: living status and housing ownership. The ingrained socio-cultural nature of rural Thailand promotes values such as caring for and respecting the elderly30. The study found that more than 90 percent of the elderly had their own homes and did not live alone. Therefore, these two indicators are important for the identification of safety of the elderly in rural Thailand.

The nine factors developed the S-AAI score of the elderly in rural lower northern Thailand, indicating that their scores were moderate (0.65), similar to other studies that use large data at the national level in Thailand2,18,24 and other local studies8,10. There was no difference between genders in our study, which was inconsistent with other studies in Thailand2,18,24 and in several European countries31 that found that male elderly individuals had a higher index than their female counterparts. However, we found gender differences in some factors of elderly males had better active aging scores than females, including mental/subjective health, physical health, and secure living. In contrast, older women scored higher than men in terms of health behaviors, chronic diseases, and stability in life. Our data highlight the extreme differences between factors in the security component, with older adults in rural Thailand having the most secure lives (0.91), whereas stability in life (0.44) and financial stability (0.50) scored the lowest. The classification of scores by age group showed that the elderly tended to decline in scores, which was particularly evident in health conditions, except for the stability of life of the elderly in rural Thailand, which increased with age. These findings are unique to rural communities in Thailand. There is evidence to support differences between urban and rural communities in other countries32. This highlights the need to consider the variations in active aging in different regions of Thailand, as each area has different cultural characteristics6.

Conclusion

In summary, health potential is the first condition for independent and self-reliant living, which is a key characteristic of older adults. As for the elderly's continued participation in activities, it not only gives them a sense of self-esteem but also a perception of dignity and psychological dependency of their family. These factors help to improve the mental health of the elderly and affect their physical health. In addition, various factors of security in life also helps the elderly experience physical security from safe living and economic security that gives them confidence to lead a quality life. The results of this study indicate that elderly people in rural areas in the lower northern Thailand have a moderate active aging index. Although there are some problems with financial stability, there is government support in terms of both pension and health insurance.

Implications

The S-AAI tool can be used as a quantitative measure for older adults in rural communities to self-assess active aging, and potentially used in questionnaires or interviews in research and practice. Local administrators and related officials can apply the indicators that are the main components of the S-AAI for the rural elderly as a guideline for planning to improve the quality of life of the elderly. Finally, this tool can be developed further to make it more widely available. The new tool can be used to monitor active ageing outcomes at the country level and to investigate the potential of older people regarding actively participate in health and social activity to promote an active role for the older people.

Strengths and limitations

The present study has some limitations. First, although the sample was large, it was not nationally representative, and other areas of Thailand may have different indicators of active aging. Therefore, further studies are needed to externally validate assessment tools developed in various cultural contexts. Second, as this study focuses on rural Thai culture, it cannot be generalized in other countries that may have different cultural contexts regarding certain S-AAI indicators such as housing and social activities, health services, etc. Third, due to the different environments in urban and rural areas, there is diversity in their economic structure, social participation, and demographics in the local community. Accordingly, the developed measuring tool may not be the same for older people in urban areas. Therefore, the study was limited to the development of measurement instruments for rural communities. Fourth, there are 5 research assistants to collect data, which may affect the data, especially the interviews with the older person who cannot read and write. However, the researcher has already controlled the quality of the data by training the research assistants prior to the fieldwork of data collection regarding the overview and objective of the research and the research techniques until they achieved research skills in data collection. Lastly, the study has not examined the psychometric properties of the S-AAI used for reliability, which is our next study, including confirmation factor analysis.

The strength of this study is that the indicators of active aging at the individual level were used comprehensively in many dimensions as the foundation for further development. The novelty of some indicators that are important in the elderly but have not yet been compiled in Thailand, namely oral health and nutritional status, were included in this study. Finally, the development of a scale for active aging assessment is a quantitative structure that allows participants to self-assess.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

World Health Organization. Ageing and health, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (2021).

National Statistical Office. Active Ageing Index of Thai elderly. (Statistical Forecasting Division, National Statistical Office, Ministry of Digital Economy and Society, Thailand., 2017).

World Health Organization. Active ageing: a policy framework. (World Health Organization, 2002).

World Health Organization. Global age-friendly cities: a guide, http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Global_age_friendly_cities_Guide_English.pdf (2007).

Thanakwang, K., Isaramalai, S. A. & Hatthakit, U. Development and psychometric testing of the active aging scale for Thai adults. Clin. Interv. Aging 9, 1211–1221. https://doi.org/10.2147/cia.s66069 (2014).

Haque, M. N. Active ageing level of older persons: Regional comparison in Thailand. J. Aging Res. 2016, 9093018. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/9093018 (2016).

Rittisorn, N. Development and changes in the Human Capital Index among pre-retirement population in Thailand-2011 through 2017. J. Educ. Hum. Resource Dev. 7, 1–13 (2019).

Punyakaew, A., Lersilp, S. & Putthinoi, S. Active ageing level and time use of elderly persons in a Thai Suburban Community. Occup. Ther. Int. 2019, 7092695. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7092695 (2019).

Pekalee, A., Ingersoll-Dayton, B., Gray, R. S., Rittirong, J. & Völker, M. Applying the concept of successful aging to Thailand. J. Popul. Soc. Stud. 28, 175–190 (2020).

Petcherut, S., Surachai, P. & Pannee, B. Active aging, health literacy, and quality of life among elderly in the Northeast of Thailand. Indian J. Forensic Med. Toxicol. 15, 2645–2650. https://doi.org/10.37506/ijfmt.v15i3.15704 (2021).

Gonçalves, J. et al. Selfie Aging Index: An index for the self-assessment of healthy and active aging. Front. Med. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2017.00236 (2017).

Paúl, C., Teixeira, L. & Ribeiro, O. Active aging in very old age and the relevance of psychological aspects. Front. Med. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2017.00181 (2017).

Hsu, H.-C., Liang, J., Luh, D.-L., Chen, C.-F. & Lin, L.-J. Constructing Taiwan’s Active Aging Index and applications for international comparison. Soc. Indic. Res. 146, 727–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02128-6 (2019).

Rantanen, T. et al. Developing an assessment method of active aging: University of Jyvaskyla Active Aging Scale. J. Aging Health 31, 1002–1024. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264317750449 (2019).

Zaidi, A. & Um, J. The new Asian Active Ageing Index for ASEAN+3 a comparative analysis with EU member states. J. Asian Sociol. 48, 523–558. https://doi.org/10.2307/26868275 (2019).

Pham, V. T., Chen, Y.-M., Van Duong, T., Nguyen, T. P. T. & Chie, W.-C. Adaptation and validation of Active Aging Index among older Vietnamese adults. J. Aging Health 32, 604–615. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264319841524 (2020).

Haque, M. A. & Afrin, S. Active Aging Index in Bangladesh: A comparative analysis with a European approach. Ageing Int. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-021-09429-7 (2021).

Haque, M. N., Soonthorndhada, K., Hunchangsith, P. & Kanchanachitra, M. Active ageing level in Thailand: A comparison between female and male elderly. J. Health Res. 30, 99–107 (2016).

Paúl, C., Ribeiro, O. & Teixeira, L. Active ageing: An empirical approach to the WHO model. Curr. Gerontol. Geriatrics Res. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/382972 (2012).

Zaidi, A. & Stanton, D. Active Ageing Index 2014: Analytical Report (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, 2015).

Kitreerawutiwong, N., Keeratisiroj, O. & Mekrungrongwong, S. Predictive factors for the sense of community belonging among older adults in lower northern Thailand. Iran. J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 14, e105564. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijpbs.105564 (2020).

Kyriazos, T. A. Applied psychometrics: sample size and sample power considerations in factor analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in general. Psychology 9, 2207–2230. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2018.98126 (2018).

Thiamwong, L., Stewart, A. L. & Warahut, J. Development, reliability and validity of the Thai healthy aging survey. Walailak J. Sci. Technol. 6, 167–188 (2009).

Thanakwang, K. & Soonthorndhada, K. Attributes of active ageing among older persons in Thailand: Evidence from the 2002 survey. Asia Pacific Popul. J. 21, 113–135. https://doi.org/10.18356/5e5fdd09-en (2007).

Lak, A., Rashidghalam, P., Myint, P. K. & Baradaran, H. R. Comprehensive 5P framework for active aging using the ecological approach: An iterative systematic review. BMC Public Health 20, 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-8136-8 (2020).

Rattanapun, S., Fongkeaw, W., Chontawan, R., Panuthai, S. & Wesumperuma, D. Characteristics healthy ageing among the elderly in Southern Thailand. Chiang Mai Univ. J. Nat. Sci. 8, 143–160 (2009).

Foster, L. & Walker, A. Active and successful aging: A European policy perspective. Gerontologist 55, 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu028 (2015).

de Souza, B. L., Lima-Costa, M. F., César, C. C. & Macinko, J. Social inequalities on selected determinants of active aging and health status indicators in a large Brazilian city (2003–2010). J. Aging Health 28, 180–196 (2016).

Huang, A. R. et al. Hearing Impairment and Loneliness in Older Adults in the United States. J. Appl. Gerontol. 40, 1366–1371. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464820944082 (2021).

Laiphrakpam, M. & Aroonsrimorakot, S. Review of indicators on active ageing towards sustainable development in Thailand. Inter. Res. Rev. 13, 41–50 (2018).

Steinmayr, D., Weichselbaumer, D. & Winter-Ebmer, R. Gender differences in active ageing: Findings from a new individual-level index for European Countries. Soc. Indic. Res. 151, 691–721. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02380-1 (2020).

Muhammad, T., Srivastava, S., Hossain, B. & Paul, R. Decomposing rural–urban differences in successful aging among older Indian adults. Sci. Rep. 12, 6430. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09958-4 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding

The author (s) disclose receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was supported by Provincial Cluster: Lower Northern Provincial Cluster 1 on academic services.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.K., N.K. and S.M. contributed to the study conception and design, material preparation, data collection; O.K. contributed to the data analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by O.K. and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Keeratisiroj, O., Kitreerawutiwong, N. & Mekrungrongwong, S. Development of Self-Active Aging Index (S-AAI) among rural elderly in lower northern Thailand classified by age and gender. Sci Rep 13, 2676 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-29788-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-29788-2

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.