Abstract

This study aimed to analyse the role of governmental responses to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak, measured by the Containment and Health Index (CHI), on symptoms of anxiety and depression during pregnancy and postpartum, while considering the countries’ Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) and individual factors such as age, gravidity, and exposure to COVID-19. A cross-sectional study using baseline data from the Riseup-PPD-COVID-19 observational prospective international study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04595123) was carried out between June and October 2020 in 12 countries (Albania, Brazil, Bulgaria, Chile, Cyprus, Greece, Israel, Malta, Portugal, Spain, Turkey, and the United Kingdom). Participants were 7645 pregnant women or mothers in the postpartum period—with an infant aged up to 6 months—who completed the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) or the Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7) during pregnancy or the postpartum period. The overall prevalence of clinically significant depression symptoms (EPDS ≥ 13) was 30%, ranging from 20,5% in Cyprus to 44,3% in Brazil. The prevalence of clinically significant anxiety symptoms (GAD-7 ≥ 10) was 23,6% (ranging from 14,2% in Israel and Turkey to 39,5% in Brazil). Higher symptoms of anxiety or depression were observed in multigravida exposed to COVID-19 or living in countries with a higher number of deaths due to COVID-19. Furthermore, multigravida from countries with lower IHDI or CHI had higher symptoms of anxiety and depression. Perinatal mental health is context-dependent, with women from more disadvantaged countries at higher risk for poor mental health. Implementing more restrictive measures seems to be a protective factor for mental health, at least in the initial phase of the COVID-19.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

After the World Health Organization’s declaration of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) global pandemic on March 11th, 2020, a wide range of non-pharmaceutical interventions were rapidly implemented by governments in many countries1,2, in an attempt to reduce the burden of the disease and allow healthcare systems to better prepare and respond3. These measures, which included restrictions on social contact and activities, had significant economic and societal impacts, namely in terms of mental health4,5, and health-related quality-of-life6 and therefore should be considered to fully understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on global mental health.

Exposure to natural disasters or stressful life events are major contributors to mental health disorders among pregnant and postpartum women7, highlighting the importance of mental health surveillance during the current COVID-19 pandemic, as exacerbation of negative emotional outcomes in these women may be expected8,9. Studies carried out during the pandemic have reported higher rates of prenatal depression varying from 25 to 45,4%10,11,12,13,14, and as high as 43% for the postpartum period11,15 compared with the pre-pandemic period. Additionally, the prevalence of anxiety almost doubled compared to pre-pandemic rates16,17,18, ranging from 30,5 to 48,8% in pregnant women10,11,12,13,14, and as high as 61% in the postpartum period12,13,15.

Monitoring anxiety and depression in the perinatal period is extremely important because it is linked not only to adverse impacts on mothers’ well-being and physical health19 but also to suboptimal child development, including compromised physical and cognitive development, behavioural problems, and increased risk of mental disorders20.

Importantly, not all women seem to be equally affected21, with a higher risk for perinatal mental disorders found among those living in socioeconomically disadvantaged contexts22,23, highlighting the influence of socioeconomic inequalities on perinatal mental health during the pandemic.

Therefore, this study aimed to analyse for the first time the role of governmental measures—using the Containment and Health Index (CHI)—on symptoms of depression and anxiety in pregnant and postpartum women, while considering countries’ Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) scores and individual factors such as age, gravidity, and COVID-19 exposure.

Methods

Study design and setting

Setting

This was a cross-sectional study using baseline data from the Riseup-PPD-COVID-19 observational prospective international study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04595123). The method has been previously described in detail elsewhere24. Briefly, pregnant and postpartum women were invited to participate in the study through social media, networks of organisations (including universities, health care services, perinatal mental health non-government organisations), policymakers, local organisations, and other stakeholders, as well as networks of colleagues and acquaintances of the research teams. Participants were also recruited directly by message or email (only researcher’s personal contacts were targeted).This study received ethical approvals in each country from which data was gathered and has been performed in accordance with the latter amendments of Declaration of Helsinki and with the Regulation (EU) 2019/679 of the European Parliament and the Council of April 27 2016 on the protection and transfer of personal data (GDPR).

The study was carried out in 12 countries, Albania (n = 37), Brazil (n = 865), Bulgaria (n = 84), Chile (n = 444), Cyprus (n = 469), Greece (n = 713), Israel (n = 549), Malta (n = 263), Portugal (n = 1422), Spain (n = 828), Turkey (n = 1426), and the United Kingdom (n = 545), from June to October 2020.

Participants

Pregnant women or mothers in the postpartum period—with an infant aged up to 6 months—were eligible to participate in the study. Further inclusion criteria were: (1) at least 18 years of age and (2) living in one of the 12 eligible countries.

Between June 7th and October 31st, 2020, 15,611 potential participants accessed the questionnaire link. Of these, 1,798 (11.5%) did not provide information regarding the eligibility criteria, and 260 (1.7%) were not eligible for participation after responding to the eligibility questions.

Therefore 13,553 potentially eligible participants gave their informed consent. Of these, 2,965 (21.9%) were excluded due to incomplete questionnaires (e.g., not providing answers beyond the eligibility questions; n = 2553), incongruent data (e.g., date of birth of child indicating that the child is older than 6 months; n = 300) or duplicate responses (verified by checking answers with the same contact information—e.g., email address—and matching sociodemographic data; n = 112). From the remaining 10,588 participants, only women who completed the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) or the Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7) were included in this analysis, yielding a final sample of n = 7,645.

Measures

The questionnaire was initially developed in English and translated into the participating countries’ languages using back translation, as described in detail elsewhere24.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Sociodemographic information included age, country of birth, country of residence, educational level (secondary education or lower vs. higher education), cohabitation with a partner (no vs. yes), professional status (employed vs. unemployed), gravidity (primigravida vs multigravida), exposure to COVID-19 (no vs. yes if exposed to at least one of the following: history of COVID-19 diagnosis, COVID-19 related symptoms, direct physical contact with an infected person, or death of a relative with COVID-19), and history of mental health problems (no vs. yes if at least one of the following: previous treatment for mental health problems, previous treatment for substance abuse, previous untreated mental health problems, and previous untreated substance abuse).

Governmental responses to the COVID-19 outbreak and number of deaths due to COVID-19

The CHI developed by Hale, Petherick, Phillips, Webster was used to evaluate the level of governmental response across the COVID-19 pandemic period under assessment1 It is calculated based on the following composite of closure, containment, and health measures: schools closing, workplaces closing, cancelled public events, restrictions on gatherings, closing of public transport, stay-at-home requirements, restrictions on in-country movements, international travel restrictions, public information campaigns, testing policies, contact tracing, face coverings, vaccination policies, and protection of older adults. Higher CHI indicates greater levels of government restrictions. In order to assess the women’s exposure to countries’ CHI, we used the area under the curve of the CHI 30 days before the completion of the questionnaires for each woman. The number of deaths per million at the time of questionnaire completion was used to indicate the impact of COVID-19 on each country’s population. We used the information available online at ‘“our world data”25.

Country development index

The United Nations developed the IHDI to capture the distribution among a country’s population of its achievements in health, education, and income, accounting for inequality level. We used the 2019 estimates of the IHDI available online26. Higher IHDI indicates better national achievements in these areas.

Symptoms of depression

The EPDS27 was used to assess the depression symptoms. It is a ten-item self-report inventory with a four-point Likert scale. Total scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating higher symptoms. The threshold of 13 or more was used to indicate clinically significant symptoms of depression28, and the reliability was very good (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.881).

Symptoms of anxiety

GAD-729 was used to assess the severity of anxiety symptoms. This is a seven-item self-report questionnaire with a four-point Likert scale. It was developed based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV and DSM-IV-Text Revision criteria. Total scores range from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating higher symptoms. The threshold of 10 or more was used to indicate clinically significant anxiety symptoms16,30, and the reliability was very good (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.903).

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis was conducted of the country-related and individual-related variables, alongside GAD-7 and EPDS total scores -, as both binary (GAD-7 ≥ 10 vs. GAD-7 < 10; EPDS ≥ 13 vs. EPDS < 13) and continuous variables. Median (Mdn) and interquartile (IQ) range were computed for continuous variables, and absolute frequencies and percentages were computed for categorical variables.

Multivariate analyses were performed separately for pregnant and postpartum women, with GAD-7 or EPDS continuous scores as dependent variables, according to gravidity (primigravida vs multigravida), COVID-19 exposure, living with a partner (no vs yes), history of mental health problems (no vs yes), age (in years), and country-related covariates (CHI, deaths per million, and IHDI), and intra-country correlation (since it is expected that women from the same country are more closely related to each other than to women from other countries). Missing data were not imputed; therefore, 353 women without data on age and three without data on gravidity were not included in the models. The models were fitted using a negative binomial regression model based on Generalized Additive Mixed Models31, to consider possible non-linear effects of the continuous variables using thin plates splines. A sensitivity analysis was conducted, not including Albania, Bulgaria, and Malta since these countries had sample sizes < 30024.

Descriptive analyses were carried out in statistical software SPSS, version 26.0, while multivariate regression analyses were carried out in the statistical software R (R Core Team, 2020), version 4.1.0, using the GJRM, mgcv, and ggplot2 packages.

Role of the funding source

The study's funding sources had no role in study design, data collection, data analyses, data interpretation, or report writing.

Ethical approval

This protocol and the template of informed consent forms were reviewed and approved by the followings Ethics Committees: Bedër University College, Albania (Ethics protocol: 145); Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski”, Bulgaria (Ethics protocol approved 21th June 2020); Cyprus National Bioethics Committee (Ethics protocol: EEBK ΕΠ 2020.01.126); France (EThics approval: Ref. N°: 20.11.16.46440/CPP2020–11-100b/2020- A02289–30); American College of Greece (Ethics protocol: #202005207); Bar Ilan University School of Social Work, Israel (Ethics approval 062001); University of Malta (Ethics protocol: FRECMDS_1920_179); University of Minho, Portugal (Ethics Protocol: CEICVS 045/2020); Andalusian Ministry of Health, Spain (Ethics Protocol: 1257- N-20); Kırklareli University, Turkey (Ethics protocol: 35523585–199-E.8606); King’s College London, the United Kingdom (Ethics protocol: ID 19747); National University of Entre Ríos, Argentina (Ethics Protocol: CD 610/09); Mackenzie Presbyterian University, Brazil (Ethics Protocol: 31155120.7.0000.0084); Universidad de Concepcion, Chile (Ethics Protocol: CEC 13/2020 and CEBB 704–2020). Participants gave their informed consent via online, and protection of personal data was ensured by adherence to guidelines and regulations in each country.

Results

A total of 7,645 women, either pregnant (n = 3,503) or in the postpartum period (n = 4,142) were considered in these analyses. Table 1 shows the participant’s characteristics. Multigravida, either pregnant or in the postpartum period, were older (p < 001/p < 001), were less exposed to COVID-19 (p = .003/p < .001), and lower education levels compared with primigravida (p = .001/p = 019). Postpartum women were older (p < 001), were more exposure to COVID-19 (p = .031), and lower rates of unemployment (p < 001) compared to pregnant women.

Data from country-related variables are displayed in Table 2. Brazil and Turkey had the lowest IHDI, whereas Bulgaria and Malta had the lowest median CHI. Within the study period, the total deaths per million were highest for Spain, Brazil, and Chile.

The prevalence of the overall clinically significant symptoms of depression and anxiety varied widely across countries (Table 3). The overall rate for clinically significant symptoms of depression in pregnant women was 26.8% (ranging from 18.2% in Cyprus to 37.7% in Brazil), and 32.7% (ranging from 17.6% in Albania to 47.2% in Brazil) in postpartum women. The prevalence of clinically significant anxiety symptoms in pregnant women was 20.1% (12.7% in Turkey to 36% in Chile) and 26.6% (ranging from 13.2% in Israel to 41.9% in Brazil) in postpartum women.

Factors associated with symptoms of anxiety

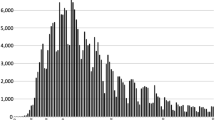

The results of the fixed effects of the generalised additive mixed models with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are shown in Table 4. Exposure to COVID-19 and previous history of mental problems were associated with increased anxiety symptoms in pregnant and postpartum women. The total number of deaths per million due to COVID-19 was associated with increased anxiety symptoms in the postpartum women and living with the partner was associated with decreased anxiety in pregnant women. IHDI and CHI had a differential association with anxiety among pregnant and postpartum women. Multigravida tended to have higher anxiety in lower IHDI contexts. The association of anxiety with CHI was non-linear for postpartum women (Fig. 1). Symptoms of anxiety were highest for CHI around 50 (a score below the median for most of the countries in the data collection period) and lowest for CHI around 65 (a score close to the maximum score in most countries in the data collection period). Women’s age was associated with anxiety symptoms; this was a linear association for postpartum women (symptoms of anxiety decreased with age) and a non-linear association for pregnant women (lower anxiety symptoms in women aged between 30 and 40 years; Fig. 2). A sensitivity analysis excluding data from Albania, Bulgaria, and Malta yielded similar results (Supplementary Table 1; Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2).

Factors associated with symptoms of depression

The results of the fixed effects of the generalised additive mixed models are shown in Table 4. Symptoms of depression were lower for primigravida compared to multigravida for pregnant women. COVID-19 exposure, not living with a partner and previous history of mental problems and the total number of national deaths per million were associated with increased depression in pregnant and postpartum women. Total number of national deaths per million were associated with increased depression in postpartum women.

Both IHDI and CHI were associated with symptoms of depression in multigravida women. Specifically, symptoms of depression increased in lower IHDI contexts in both pregnant and postpartum women and in lower CHI contexts only in pregnant women. The association between symptoms of depression and CHI in postpartum women was non-linear (Fig. 1). Symptoms of depression were highest for CHI around 47 (a score below the median for most of the countries in the data collection period) and lowest for CHI around 66 (a score close to the maximum score in most countries in the data collection period). Women’s age was associated with depression symptoms; this was a linear association for postpartum women (symptoms of depression decreased with age) and a non-linear association for pregnant women (lower symptoms of depression in women aged between 30 and 40 years; Fig. 2). A sensitivity analysis excluding data from Albania, Bulgaria, and Malta yielded similar results (Supplementary Table 1; Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2).

Discussion

Overall, our data demonstrated that during the COVID-19 pandemic, one in four women during pregnancy and one in three women in the postpartum had clinically significant symptoms of depression. One in five women during pregnancy and one in four women in the postpartum had clinically significant symptoms of anxiety. Additionally, more robust governmental responses to the COVID-19 outbreak, measured by the CHI, were associated with lower symptoms of anxiety in the postpartum period and depression during the perinatal period. Furthermore, previous history of mental health problems and exposure to COVID-19 were important determinants of anxiety and depression regardless of the perinatal period. Individual determinants such as gravidity were associated specifically with depression in pregnancy and living with the partner showed to be protective of mental health problems during pregnancy and protective of depression during the postpartum period. National deaths per million due to COVI D-19 was associated with mental health problems only in the postpartum. Furthermore, multigravida women from countries with lower IHDI or CHI were more likely to have higher symptoms of depression or anxiety in the postpartum period. Moreover, symptoms of depression and anxiety decreased with age in postpartum women, whereas during pregnancy, lower symptoms of depression and anxiety were observed between the ages of 30 and 40 years.

Prevalence of clinically significant symptoms of anxiety and depression

The overall rates of clinically significant symptoms of depression are alarming and, although there are variations between countries, even in countries with lower rates—Cyprus, Greece, and Albania—at least one in four women had clinically significant symptoms of depression. In 6/12 countries, the rates were above 30%, including Spain, Turkey, Malta, Chile, the United Kingdom (UK), and Brazil. Other studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic reported even higher rates of clinically significant depressive symptoms during pregnancy (37%) using the same instrument and cut-off32. Nonetheless, our rates are higher than those found in a cross-country study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic (June to July 2020) in Ireland, Norway, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and the UK, in which rates of clinically significant depression symptoms were about 15% for pregnant women and 10% for postpartum women33. Although in our study Spain is among the countries with higher rates of clinically significant depression symptoms (30.4%), even higher rates were reported in a recent study (58%) conducted by Chavez et al.34 in which an EPDS cut-off of 11 was used instead of 13, increasing the number of individuals scoring above the threshold. Turkey also had high rates of clinically significant depression symptoms, mirroring the results of a recent study showing a prevalence of 35.4% among pregnant women in Turkey35. In the UK, Fallon et al.15 reported slightly higher rates in postpartum women (43.0%) than in our study (39.3%). In Brazil, a recent study with a cohort of women in the postpartum period from a city located in the south of the country reported that 29.3% clinically significant symptoms of depression36. While this rate is lower than reported in our study (47.2%), it should be noted that it pertains to a specific city and that some women were assessed over the 12-month postpartum period when peak symptoms occur.

In three-quarters of the countries (9/12) evaluated in this study, at least one in five women displayed clinically significant anxiety symptoms, lower than the frequency of clinically significant depression symptoms in all countries except Albania, Chile, and Spain. Other researchers have found higher rates of clinically significant symptoms of anxiety compared to depression during pregnancy in the pandemic period, for instance, in Canada (57–37%), Iran (43.9–32.7%) or China (31.2–19.2%)23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38, which concurs with our data regarding some countries (Albania, Chile, and Spain). Whether cultural or COVID-19-related factors are responsible for these differences remains to be understood since we lack pre-pandemic data. In the current study, the rates of clinically significant anxiety and depression symptoms were higher in the postpartum period than during pregnancy in most countries except Albania, Bulgaria, and Israel (and Chile, regarding depression only), which indicates that postpartum women are at a higher risk of mental health problems then pregnant women, as previously reported39. This evidence highlights the importance of implementing responsive and adequate mental health services for postpartum women to overcome barriers to care during this period (e.g., availability of childcare facilities/staff and breastfeeding support).

Individual Factors associated with depression and anxiety

Individual determinants such as previous history of mental health problems are important determinants of anxiety and depression regardless of the perinatal period. Pre-existing mental health conditions are a well -known risk factor for perinatal mental health problems and have been associated with higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms in other studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic in the general population40 and in the perinatal period41.

Aditionally, living with the partner seems to be protective of both anxiety and depression during pregnancy and protective of depression during the postpartum period, in line with previous evidence42.This may be due to the fact that social support is protective of perinatal mental health18 and partner support is perceived by pregnant women as one of the most important sources of social support during the COVID-19 pandemic14. Moreover, gravidity is associated specifically with depression in pregnancy, which is in line with other studies and may be explained by the fact that multiparous women are exposed to additional burden related to their pre-existing parenting challenges11. Additionally, symptoms of depression and anxiety decreased with age in postpartum women, whereas during pregnancy, lower symptoms of depression and anxiety were observed between the ages of 30 and 40 years. Others studies have consistently associated younger ages with mental health problems among women in the perinatal period18,33. The higher scores for depression and anxiety in older women during pregnancy but not in the postpartum period, might be related with the cumulative threat of the COVID-19 disease and of the age by itself that is a well-known risk factor for perinatal and neonatal outcomes.

Impact of governmental responses to COVID-19 outbreak

Governmental responses to control the spread of COVID-19 differed between countries. Increased CHI was associated with decreased symptoms of depression or anxiety during the postpartum period; thus, the number and intensity of closure and containment policies and those aimed at disease surveillance were protective of women’s perinatal mental health. Other studies conducted during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, also showed decreased depression and anxiety symptoms with more strict restriction measures40, as well as a positive perception on lockdowns and improvements in perceived mental well-being43 in the general population. Still, conflicting evidence highlight the potentially negative impact of such restrictive measures (namely social isolation) and the potential burden in terms of mental health outcomes44,45,46,47.

These apparently contradictory results should be carefully interpreted since there are several methodological differences between studies. In our study we used a cross-country comparable Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT), an index based on several specified indicators capturing variation in the restriction level of governmental responses, while other’s studies14,15 have relied on self-report questionnaires to assess individual perceptions of restrictions particularly focused on isolation and social support/distance. One explanation for our results could be that the COVID-19 pandemic represents uncertainty (at the social, economic, and health levels) and that these governmental interventions may be perceived as protective, especially for vulnerable populations such as perinatal women, reassuring individuals and providing them with a sense of security and control over this challenging situation22.

Interestingly, multigravida women were the most ‘sensitive’ to both the governmental measures and to the IHDI. Regarding CHI, the pattern found for multigravida women is different for the one found in primigravida women which could be explained by the additional parenting challenges for multigravida. Some studies showed that the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with parenting-related exhaustion particularly for women or having higher number of children or younger children48.

We also observed that women living in countries with high IHDI displayed lower symptoms of anxiety and depression. Every increase of 0.1 points on the IHDI led to a decrease of 10.4–13.9% in anxiety in pregnant women and in depression in both pregnant and postpartum women. This finding contrasts with the higher depression symptoms in countries with higher HDI reported in a systematic review (Lee et al., 2021). However, in those studies, the HDI was used, whereas in our study the IHDI was used. Our data highlight that exposure to multiple risk factors (characteristic of countries with higher inequalities) is associated with increased vulnerability to poor mental health. In the context of COVID-19, women in the perinatal period from resource-constrained countries may be at even higher risk of poor mental health than those countries with less inequality.

Symptoms of anxiety and depression increased with the magnitude of the pandemic’s negative effects, such as the number of deaths and exposure to COVID-19. For every 100 deaths per million, the depressive symptoms increased between 2.7 and 3.7%, and the anxiety symptoms increased between 4.4 and 5.9%. These data support the assumption that COVID-19 may lead to national mental health crises, particularly in countries with greater infection levels49. Additionally, COVID-19 exposure led to an 8.7% increase in anxiety symptoms and an 18.6% increase in symptoms of depression. Previous evidence showed that having symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 was a risk factor for mental health problems in women50.

The highest prevalence of clinically significant depression symptoms was observed in Brazil (44.3%), Chile (34.2%), and the UK (35.5%), which were the three countries with the greatest delays in the implementation of stringent lockdown measures. Considering a threshold of 20 in the governments’ stringent COVID-19 containment index51, Brazil, Chile, and the UK took 6, 9, and 12 more days, respectively, than the leading countries (Israel, Greece, and Bulgaria), to implement the same level of stringency. Previous studies indicated that symptoms of depression were higher in countries implementing these measures later51.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study is the use of reliable self-reported measures in 12 countries. The main strength of this study is the use of reliable self-reported outcome measures in 12 countries. Both the EPDS and GAD-7, are widely used in research and have good properties to estimate the prevalence of depression and anxiety28,30. However, there are noteworthy limitations to this study. First, even though the gold standard for the assessment of clinical prevalence are structured clinical interviews, applying structured interviews in large samples, and especially during the COVID-19 pandemic wouldn’t be feasible. Second, although the GAD-730 is not validated for perinatal population, this screening tool appears to capture the symptomatology and severity of the illness in pregnant and postpartum mothers52 and it is recommended by the NICE 2020 clinical guidelines53. Third, not all countries included in the present study have validated the EPDS in the perinatal period, whereas validation studies for using GAD-7 in the perinatal period are lacking for most of these countries54,55. Therefore, further research is needed to determine the validity and reliability of these screening tools during the perinatal period across different countries.

Although we could not report the impact of national inequalities on mental health, future studies with data from countries representing a wider range of IHDI sub-groups could provide further details on the impact of inequalities on perinatal mental health.

The fact that most of the participants had high levels of education is a limitation of this study. It may lead to underestimating mental health problems since a higher educational level is a protective factor for mental health problems56 and may limit the generalizability of the results. Similarly, women under 18 years old, who may be especially vulnerable to the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, were not included in the study due to ethical issues. Additionally, we do not have socio-demographic information for women excluded due to missing data, therefore we cannot compare potential differences between women included and not included in the analysis.

It is also important to note that this study reports data collected between June and October 2020, before the second wave of COVID-19 in Europe, may explain the lower rates of clinically significant symptoms of depression and anxiety in our study, specifically in the European countries, compared with other studies conducted early on in the pandemic. Additionally, the long-term impact of prolonged exposure to such restrictive governmental measures on perinatal mental health remains to be investigated.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study showed that containment health measures are associated with better prenatal mental health outcomes in the initial period of the pandemic; while in the postnatal period a non-linear effect was observed. Country-related and individual-related factors explain some of the variability in this association, with women from more disadvantaged countries at higher risk for adverse mental health outcomes. Implementing more restrictive measures seems to be especially protective in multigravida women.

A global investment in perinatal mental health care policies is urgent in order to mitigate the long-term impact of COVID-19 on women, children and families. Specific measures for vulnerable groups such as multiparous women and those from low-resources countries, should be implemented by policy makers.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Change history

03 March 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30737-2

References

Hale, T., Petherick, A., Phillips, T. & Webster, S. Variation in Government Responses to COVID-19” Version 3.0. Blavatnik School of Government Working Paper. www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/covidtracker (2020).

Kucharski, A. J. et al. Effectiveness of isolation, testing, contact tracing, and physical distancing on reducing transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in different settings: A mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20, 1151–1160 (2020).

Teslya, A. et al. Impact of self-imposed prevention measures and short-term government-imposed social distancing on mitigating and delaying a COVID-19 epidemic: A modelling study. PLoS Med. 17, e1003166 (2020).

Bäuerle, A. et al. Mental health burden of the COVID-19 outbreak in Germany: Predictors of mental health impairment. J. Prim. Care Commun. Health 11, 215013272095368 (2020).

Fayaz Farkhad, B. & Albarracín, D. Insights on the implications of COVID-19 mitigation measures for mental health. Econ. Hum. Biol. 40, 100963 (2021).

Hay, J. W. et al. A US population health survey on the impact of COVID-19 using the EQ-5D-5L. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 36, 1292–1301 (2021).

Harville, E., Xiong, X. & Buekens, P. Disasters and perinatal health: A systematic review. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 65, 713–728 (2010).

Iyengar, U., Jaiprakash, B., Haitsuka, H. & Kim, S. One year into the pandemic: A systematic review of perinatal mental health outcomes during COVID-19. Front. Psychiatry 12, 674194 (2021).

Chmielewska, B. et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 9, e759–e772 (2021).

Sun, F., Zhu, J., Tao, H., Ma, Y. & Jin, W. A systematic review involving 11,187 participants evaluating the impact of COVID-19 on anxiety and depression in pregnant women. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 42, 91–99 (2021).

Yan, H., Ding, Y. & Guo, W. Mental health of pregnant and postpartum women during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 11, 617001 (2020).

Fan, S. et al. Psychological effects caused by COVID-19 pandemic on pregnant women: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Asian J. Psychiatry 56, 102533 (2021).

Tomfohr-Madsen, L. M., Racine, N., Giesbrecht, G. F., Lebel, C. & Madigan, S. Depression and anxiety in pregnancy during COVID-19: A rapid review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 300, 113912 (2021).

Harrison, V., Moulds, M. L. & Jones, K. Perceived social support and prenatal wellbeing; The mediating effects of loneliness and repetitive negative thinking on anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. Women Birth 35, 232–241 (2022).

Fallon, V. et al. Psychosocial experiences of postnatal women during the COVID-19 pandemic. A UK-wide study of prevalence rates and risk factors for clinically relevant depression and anxiety. J. Psychiatr. Res. 136, 157–166 (2021).

Fawcett, E. J., Fairbrother, N., Cox, M. L., White, I. R. & Fawcett, J. M. The prevalence of anxiety disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period. J. Clin. Psychiatry 80, 1181 (2019).

Hessami, K., Romanelli, C., Chiurazzi, M. & Cozzolino, M. COVID-19 pandemic and maternal mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 35, 4014–4021 (2022).

Suwalska, J. et al. Perinatal mental health during COVID-19 pandemic: An integrative review and implications for clinical practice. J. Clin. Med. 10, 2406 (2021).

Howard, L. M. & Khalifeh, H. Perinatal mental health: A review of progress and challenges. World Psychiatry 19, 313–327 (2020).

Goodman, S. H. et al. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 14, 1–27 (2011).

Esteban-Gonzalo, S., Caballero-Galilea, M., González-Pascual, J. L., Álvaro-Navidad, M. & Esteban-Gonzalo, L. Anxiety and worries among pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multilevel analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 6875 (2021).

Wu, Y. et al. Perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms of pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 223(240), e1-240.e9 (2020).

Effati-Daryani, F. et al. Depression, stress, anxiety and their predictors in Iranian pregnant women during the outbreak of COVID-19. BMC Psychol. 8, 99 (2020).

Motrico, E. et al. Impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on perinatal mental health (Riseup-PPD-COVID-19): Protocol for an international prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 21, 368 (2021).

Global Change Data Lab (online). https://ourworldindata.org/. Accessed June 2021.

United Nations Development Programme (online). In.

Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M. & Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 150, 782–786 (1987).

Levis, B., Negeri, Z., Sun, Y., Benedetti, A. & Thombs, B. D. Accuracy of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) for screening to detect major depression among pregnant and postpartum women: Systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4022 (2020).

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W. & Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Arch. Intern. Med. 166, 1092 (2006).

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W. & Löwe, B. A Brief. measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Arch Intern Med 166, 1092 (2006).

Wood, S. N. Generalized Additive Models (Chapman and Hall, 2017).

Lebel, C., MacKinnon, A., Bagshawe, M., Tomfohr-Madsen, L. & Giesbrecht, G. Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 277, 5–13 (2020).

Ceulemans, M. et al. Mental health status of pregnant and breastfeeding women during the COVID-19 pandemic—A multinational cross-sectional study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 100, 1219–1229 (2021).

Chaves, C., Marchena, C., Palacios, B., Salgado, A. & Duque, A. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on perinatal mental health in Spain: Positive and negative outcomes. Women Birth 35, 254–261 (2022).

Durankuş, F. & Aksu, E. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety and depressive symptoms in pregnant women: A preliminary study. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 35, 205–211 (2022).

Loret de Mola, C. et al. Maternal mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in the 2019 Rio Grande birth cohort. Braz. J. Psychiatry 43, 402–406 (2021).

Lebel, C., MacKinnon, A., Bagshawe, M., Tomfohr-Madsen, L. & Giesbrecht, G. Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect Disord. 277, 5–13 (2020).

Zeng, X. et al. Mental health outcomes in perinatal women during the remission phase of COVID-19 in China. Front. Psychiatry 11, 571876 (2020).

Obrochta, C. A., Chambers, C. & Bandoli, G. Psychological distress in pregnancy and postpartum. Women Birth 33, 583–591 (2020).

Fancourt, D., Steptoe, A. & Bu, F. Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19 in England: A longitudinal observational study. Lancet Psychiatry 8, 141–149 (2021).

Liu, C. H., Erdei, C. & Mittal, L. Risk factors for depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms in perinatal women during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 295, 113552 (2021).

Antoniou, E., Stamoulou, P., Tzanoulinou, M.-D. & Orovou, E. Perinatal mental health; The role and the effect of the partner: A systematic review. Healthcare 9, 1572 (2021).

Hensel, L. et al. Global behaviors, perceptions, and the emergence of social norms at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Econ. Behav. Organ 193, 473–496 (2022).

Leigh-Hunt, N. et al. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health 152, 157–171 (2017).

Rogers, J. P. et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 7, 611–627 (2020).

Brooks, S. K. et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395, 912–920 (2020).

de Arriba-García, M. et al. GESTACOVID project: psychological and perinatal effects in Spanish pregnant women subjected to confinement due to the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal. Med. 35, 5665–5671 (2022).

Marchetti, D. et al. Parenting-related exhaustion during the Italian COVID-19 lockdown. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 45, 1114–1123 (2020).

Dong, L. & Bouey, J. Public mental health crisis during COVID-19 pandemic, China. Emerg. Infect Dis. 26, 1616–1618 (2020).

Ranjbar, F. et al. Changes in pregnancy outcomes during the COVID-19 lockdown in Iran. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21, 577 (2021).

Lee, Y. et al. Government response moderates the mental health impact of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of depression outcomes across countries. J. Affect. Disord. 290, 364–377 (2021).

Misri, S., Abizadeh, J., Sanders, S. & Swift, E. Perinatal generalized anxiety disorder: Assessment and treatment. J. Womens Health 24, 762–770 (2015).

NICE. Antenatal and postnatal mental health: Clinical management and service guidance Clinical guideline [CG192]. (2022).

Mateus, V. et al. Rates of depressive and anxiety symptoms in the perinatal period during the COVID-19 pandemic: Comparisons between countries and with pre-pandemic data. J. Affect. Disord. 316, 245–253 (2022).

Vogazianos, P., Motrico, E., Domínguez-Salas, S., Christoforou, A. & Hadjigeorgiou, E. Validation of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in Cypriot pregnant and postpartum women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22, 841 (2022).

Nisar, A. et al. Prevalence of perinatal depression and its determinants in Mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 277, 1022–1037 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This article is based upon work from COST Action CA18138 "Research Innovation and Sustainable Pan-European Network in Peripartum Depression Disorder" (Riseup-PPD), supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology; https://www.cost.eu/); also, by the Spanish Ministry of Health, the Institute of Health Carlos III, and the European Regional Development Fund «Una manera de hacer Europa» by the Prevention and Health Promotion Research Network ‘redIAPP’ (RD16/0007). Raquel Costa is supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) and from EU through the European Social Fund and FCT under an individual Post-Doctoral Grant SFRH/BPD/117597/2016. EPIUnit, ITR and HEI-Lab are finaced by national funds through the FCT within the scope of projects UIDB/ 04750/2020, LA/P/0064/2020, and UIDB/05380/2020. Rena Bina and Drorit Levy received funding from the Bar-Ilan Dangoor Centre for Personalized Medicine, Israel. Ana Mesquita is supported from the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) and from EU through the European Social Fund and from the Human Potential Operational Program—IF/00750/2015. The work developed by ProChild CoLAB was supported by NORTE-06-3559-FSE-000044, integrated in the invitation NORTE-59-2018- 41, aiming to hire Highly Qualified Human Resources, co-financed by the Regional Operational Programme of the North 2020, thematic area of Competitiveness and Employment, through the European Social Fund (ESF). Ana Osório received financial support from CAPES/Proex no. 0426/2021 and CAPES/PrInt Grant No. 88887.310343/2018-00. Vera Mateus received financial support from CAPES/PrInt Grant No. 88887.583508/2020-00. Carmen Cadarso-Suárez and Carla Díaz-Louzao are supported by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Spain), and by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) under the project MTM2017-83513-R, and also under the project ED431C 2020/20, financed by the Competitive Research Unit Consolidation 2020 Programme of the Galician Regional Authority (Xunta de Galicia). CAW is funded by the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) as an Academic Clinical Lecturer. We thank the Management Committee of COST Action Riseup-PPD for their support. We would also like to thank the all other researchers who are collaborating on the project as the Riseup-PPD-COVID-19 Group “: Mercedes Carrasco-Portiño (Chile), Natalia Houliara (Greece), Yanis Zervas (Greece), Areti Spyropoulou (Greece), Aggeliki Leonardou (Greece), Alexia Karain (Greece), Iliana Liakea (Greece), Patricia Moreno-Peral (Spain), Sonia Conejo-Cerón (Spain), María del Pilar Garrido-Borrego (Spain), María José Gonzalez-Vereda (Spain), Carmen Martín-Gomez (Spain), Irene Gómez-Gómez (Spain), Javier Álvarez (Spain), Carmen Rodríguez-Domínguez (Spain), María Fe Rodriguez (Spain), Ana Ganho-Ávila (Portugal), Bárbara Figueiredo (Portugal), Isabel Soares (Portugal), Adriana Sampaio (Portugal), Cristina Nogueira-Silva (Portugal), Berta Maia (Portugal), Mariana Marques (Portugal), Joana Antunes (Portugal), Rita Pereira (Portugal), Marlene Sousa (Portugal), María Fernanda González (Argentina), Marina Mattioli (Argentina), Gisele Apter (France), Emmanuel Devauche (France), Lisa Vitte (France) and Cyriaque Hauguel (France).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.M., A.M. and R.B. are the guarantors. E.M. and A.M. conceived and design the study, the other authors (R.B., S.A.-Z., S.D.-S., V.M., Y.C.-G., M.C.-P., E.A., A.U., A.C., P.D.-Y., E.F., C.H., E.V., C.A.W., R.B., E.H., D.L., A.O.) collaborated in the implementation of the protocol (namely translation and adaption whenever necessary) and recruitment of participants in each country. AM and RC prepared the initial manuscript draft and the other authors (R.B., S.A.-Z., S.D.-S., V.M., Y.C.-G., M.C.-P., E.A., A.U., A.C., P.D.-Y., E.F., C.H., E.V., C.A.W., R.B., E.H., D.L., A.O.) revised the manuscript. F.G., C.C.-S. and C.D.-L. developed the formal analysis and performed the figures. All authors (A.M., R.C., R.B., C.C.-S., F.G., C.D.-L., P.D.-Y., A.O., V.M., S.D.-S., E.V., D.L., S.A.-Z., C.A.W., Y.C.-G., M.C.-P., S.S., A.C., E.H., E.F., R.B., C.H., E.A., A.U., E.M.) have reviewed the draft critically and suggested revisions, given final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the study.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article Emma Motrico was incorrectly affiliated with ‘Department of Psychology, School of Philosophy, National and Kapodestrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece’. The correct affiliation is listed here: Psychology Department, Universidad Loyola Andalucia, Sevilla, Spain

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mesquita, A., Costa, R., Bina, R. et al. A cross-country study on the impact of governmental responses to the COVID-19 pandemic on perinatal mental health. Sci Rep 13, 2805 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-29300-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-29300-w

This article is cited by

-

Social distancing and mental health among pregnant women during the coronavirus pandemic

BMC Women's Health (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.