Abstract

Within competitive sociocultural environments, most Korean workers are likely to shorten their sleep duration during the weekday. Short sleep duration is associated with dyslipidemia; however, studies on the correlation between various sleep patterns and dyslipidemia are still lacking. In hence this study aimed to investigate the association between weekend catch-up sleep (CUS) and dyslipidemia among South Korean workers. Our study used data from the 8th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). The analysis covered 4,085 participants, excluding those who were diagnosed with dyslipidemia and not currently participating in economic activities. Weekend CUS was calculated as the absolute difference between self-reported weekday and weekend sleep duration. Dyslipidemia was diagnosed based on the levels of total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and triglycerides in blood samples collected after 9–12 h of fasting. After adjusting for sociodemographic, economic, health-related, and sleep-related factors, a negative association of weekend CUS with dyslipidemia was observed in male workers (odds ratio: 0.76, 95% confidence interval: 0.61–0.95). Further, workers with total sleep duration of 7–8 h, night workers, and white-collar workers with CUS were at relatively low risk of dyslipidemia compared to the non-CUS group. Less than 2 h of weekend CUS was negatively related to dyslipidemia in Korean workers, especially males. This suggests that sleeping more on weekends for workers who had a lack of sleep during the week can help prevent dyslipidemia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the cause of substantial social burdens worldwide and is the leading cause of death in South Korea, where the CVD-associated mortality rate has been gradually increasing recently1. Dyslipidemia, a major risk factor for CVD, is increasing in prevalence in South Korea1,2. Over the past few decades, various lifestyle changes have increased the prevalence of dyslipidemia3. Many studies have reported several risk factors for dyslipidemia, such as age, hypertension, and cigarette smoking4. As other risk factors of dyslipidemia are being reduced or controlled better than ever before, negative changes in lifestyle patterns, such as lack of exercise, excessive alcohol intakes or else, might be responsible1,5.

Sleep duration is an important part of a healthy lifestyle, and insufficient sleep is one of the most common sleep-related problems6. However, excessive sleep is also associated with worsening health status. Therefore, the importance of an optimal duration and quality of sleep has been recognized7. The international classification of sleep disorders notes that the optimal sleep duration is 7–8 h8.

In the modern age, sleep restriction often occurs for social requirements or work schedules, with a trend toward reduced sleep duration. Workers who live in an environment with a lack of sufficient sleep on weekdays due to work schedules or other causes often sleep more on weekends, which is known as weekend catch-up sleep (CUS). Weekend CUS is calculated as the absolute difference between the weekday and weekend sleep duration9.

Most workers make up for their short weekday sleep with extended weekend sleep10. According to previous studies, catching up on sleep on weekends appears to limit the comorbid risks associated with sleep debt11. Short sleep duration is associated with dyslipidemia12, but studies on the correlation between the various patterns of sleep and dyslipidemia are still lacking. Hence, this study aimed to investigate the association between weekend CUS and dyslipidemia among Korean workers using a nationally representative sample of Korea. We hypothesized that making up for sleep over the weekend would be associated with a lower risk of dyslipidemia. We also identified the relationship between dyslipidemia according to the difference in CUS through subgroup analysis.

Methods

Data

The study data were obtained from the 2019 and 2020 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). The KNHANES is a cross-sectional nationwide survey and is conducted by the Korean Center for Disease Control and Prevention13. The KNHANES provides a nationally representative sample of the South Korean population residing in Korea, using a complex and multistage clustered probability design.

Participants

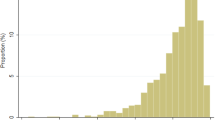

The current study used data from the 2019 and 2020 KNHANES, which contains data from 15,469 participants. Participants < 19 years of age (n = 2,730) were excluded from this study. As we aimed to analyze workers, we also excluded individuals not currently participating in economic activities (n = 5,371). In addition, those who were diagnosed with dyslipidemia and current is currently undergoing treatments (n = 1,207) or had missing data (n = 2,076) were excluded. Finally, the study comprised of 4,085 participants (2,206 males and 1,879 females). This study did not require prior consent or approval from an Institutional Review Board because the KNHANES is a secondary dataset and consists of already de-identified data available in the public domain.

Variables

The main variable of interest was weekend CUS calculated using the average weekday and weekend sleep duration from the relevant KNHANES questionnaire. Participants’ average weekday and weekend sleep durations were calculated based on their responses to the following questions: On a weekday (or working day), at How many hours do you usually sleep a day? On a weekend (or the day when you do not work, the day before you do not work), How many hours do you usually sleep a day? Weekend CUS was defined as sleep duration in the weekend being longer than that in weekdays14 Weekend CUS was calculated as the average weekend sleep duration minus the average weekday sleep duration.. Participants were then divided into non-CUS (≤ 0 h) and CUS (0 > h) groups10. Additionally, we classified CUS duration into 0 < to 1, 1 < to 2, and > 2 h for subgroup analysis.

The dependent variable was the prevalence of dyslipidemia diagnosed based on the levels of total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and triglycerides in blood samples collected after 9–12 h of fasting. According to the 2018 Korean Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia, for diagnosis of dyslipidemia, one of the following four criteria was required: (1) total cholesterol ≥ 240 mg/dL, (2) HDL cholesterol ≤ 40 mg/dL, (3) LDL cholesterol ≥ 160 mg/dL, or (4) triglycerides ≥ 200 mg/dL15.

The following covariates were included in the analyses: The sociodemographic factors were age (19–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, and ≥ 60 years) and sex (male and female). The socioeconomic factors were education level (middle school or lower, high school, or university or higher), region (metropolitan or rural area), marital status (married or unmarried), occupation (white collar, pink collar, blue collar), and household income (high, middle-high, middle-low, or low). The health-related factors were obstructive sleep apnea calculated by STOP-bang (yes or no), alcohol consumption status (less 1 time per month, 2–4 times per months, over 2 times per week) and smoking status (yes or no). In addition, adjustments were made for average total sleep duration (< 7,7–8,8 <), work pattern (day, night, shift work), physical activity (yes or no), body mass index (underweight, normal, overweight), menopause status (yes or no), hypertension (yes or pre-hypertension or no), and diabetes (yes or prediabetes or no).

Statistical analyses

Owing to sex differences in physical conditions, all analyses were stratified by sex16. Descriptive analysis using by chi-square test was performed to examine the distribution of the general characteristics of the study population. Multiple logistic regression modelling was used to assess the association between CUS and prevalence of dyslipidemia after adjusting for all covariates. In addition, to find out the association according to the subdivided categories of weekend CUS and dyslipidemia, multiple logistic regression analyses of subgroups were also performed. ORs and 95% CIs were calculated to compare the data of participants with dyslipidemia. Variables were clustered, stratified, and weighted to account for the limited proportion of participants retained in the final analysis17. SAS (version 9.4M6; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the general characteristics of the study population, stratified by sex. Of the 4,085 participants, 2,206 were males and 1,879 were females. Of these, 1,290 individuals (881 males and 409 females) had dyslipidemia. The prevalence of dyslipidemia was greater among non-CUS workers compared to those who had weekend CUS (non-CUS: 544/1,267, 42.9%; CUS: 337/939, 35.9%). A similar trend was observed among females (non-CUS: 253/1,036, 24.4%; CUS: 156/843, 18.5%).

Table 2 presents the results from the multiple logistic regression analysis of the association between CUS and dyslipidemia. There was a significant association in males between weekend CUS and dyslipidemia (odds ratio [OR]: 0.76, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.61–0.95). However, no such association was found for females.

The results of the subgroup analysis stratified by total sleep duration, work pattern, and occupational categories are shown in Table 3. Male CUS workers who slept for a total average of 7–8 h were less likely to have dyslipidemia compared to non-CUS workers (OR: 0.70, 95% CI: 0.52–0.94). Similarly, male CUS workers with white-collar jobs were at less risk of dyslipidemia compared to non-CUS workers (OR: 0.68, 95% CI: 0.49–0.94). Regardless of sex, night workers with CUS showed a significant association between weekend CUS and dyslipidemia compared to those without CUS (male: OR: 0.38, 95% CI: 0.18–0.83, female: OR: 0.30, 95% CI: 0.13–0.73).

Table 4 shows the results of subgroup analysis stratified by classified CUS. Males who had ≤ 2 h of CUS were significantly less likely to have dyslipidemia (0 < CUS ≤ 1: OR: 0.74, 95% CI: 0.55–0.998, 1 < CUS ≤ 2: OR: 0.64, 95% CI: 0.47–0.89). This association was not observed in females.

Discussion

In this study, we found that Korean male workers with ≤ 2 h of CUS had a decreased risk of dyslipidemia compared to those without CUS after adjusting for potential covariates. Further, workers with a total sleep duration of 7–8 h, night workers, and white-collar workers with CUS were at relatively low risk of dyslipidemia compared with those without CUS.

Sleep is an important factor in healthcare18. Reduced sleep quality or sleep duration could be risk factors for poor physical and psychological health19,20. Other studies have shown that excessive sleep has adverse effects on health outcomes21. Optimal sleep management is essential for healthcare, but most Koreans, especially those who work, do not get enough sleep22,23. Although most people have different lifestyles, Korean workers tend to make up for their lack of sleep on weekdays with weekend sleep24. According to studies, to cope with weekly sleep deprivation, weekend CUS is undertaken, which is associated with a lower prevalence of hypertension, obesity, and serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels25,26,27. A previous epidemiological study reported that insufficient sleep duration increases the risk of CVD28. Likewise, sufficient sleep can reduce the risk of developing CVD29. This may explain our finding that supplementing insufficient sleep with weekend CUS is linked to a reduced risk of dyslipidemia.

In our study, workers who had CUS and an optimal sleep duration (7–8 h) on weekdays had a negative relationship with dyslipidemia compared to those who had abnormal sleep durations of < 7 h or > 8 h. A previous study has suggested that abnormal sleep duration during the week is associated with increased mortality in individuals < 65 years old20. Similarly, another study showed that those who had appropriate sleep with CUS had a negative correlation with obesity30. Therefore, our study suggests the need to keep an optimal sleep duration even if it is supplemented on weekends.

Night work is more strongly associated with dyslipidemia, compared to day or other shift work31. Night workers usually receive less sleep than day workers32. Sleep deprivation negatively affects metabolism and promotes the development of an atherogenic lipid profile33. This may explain our finding that night workers’ sleep supplementation on the weekend showed a negative relationship with dyslipidemia compared to day or shift workers. Furthermore, the risk of dyslipidemia is lower when there is ≤ 2 h difference in sleep time between weekdays and weekends. On the other hand, those with > 2 h difference showed a positive relationship, but it was not statistically significant. Obviously, insufficient sleep is associated with negative health effects; however, habitual excessive sleep can also increase the risk of mortality, and if the degree of misalignment is severe, the compensatory effect might disappear34,35. Hence, to protect workers from dyslipidemia, we need to identify how to attain enough sleep in general and achieve a balanced sleep duration between weekdays and weekends.

Although the results of this study serve as further evidence in clarifying the negative association between weekend CUS and dyslipidemia, especially among Korean male workers, it has some limitation. First, this study used a cross-sectional data set; thus, we could only determine the association and not investigate the causal relationship between those variables. Therefore, additional research is needed to infer an accurate causality. Second, data regarding sleep time comes from self-report questionnaires; inaccuracies may, thus, occur. As such, the possibility of a difference between actual and reported sleep time cannot be excluded. Third, due to the data limitation, potential risk factors related to sleep and dyslipidemia may existed, such as a diagnosis of insomnia or other medications which affects the levels of lipids not considered in this study.

Despite these limitations, this study has also several strengths. First, dyslipidemia was measured through clinical testing; hence, it was based on more reliable and clear data. Second, since this study was conducted on a nationally representative sample, the results reflect the overall situation in South Korea and could be used to establish health policy.

In conclusion, our results have public health significance because this research provides insight on preventing dyslipidemia, a high-burden disease, by investigating the relationship between weekend CUS and dyslipidemia. Less than 2 h of weekend CUS was negatively related to dyslipidemia, especially among male workers. Workers with 7–8 h of sleep, night workers, and white-collar workers with CUS were at relatively low risk of dyslipidemia compared to those without CUS. This suggests that properly replenishing sleep on weekends for workers with a lack of sleep on weekdays can help prevent dyslipidemia. Further studies are needed to clarify the neurobiological mechanisms underlying the association of the balance of sleep duration with dyslipidemia.

Data availability

The data analyzed in this study were taken from the 2019–2020 KNHANES which is available to the public. All data can be downloaded from the KNHANES official website (https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/).

Change history

14 February 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-29768-6

References

Korean Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia. Executive summary (english translation). KCJ 46, 275–306. https://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2016.46.3.275 (2016).

Lee, M. H. et al. Prevalence of dyslipidemia among Korean Adults: Korea national health and nutrition survey 1998–2005. DMJ 36, 43–55. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2012.36.1.43 (2012).

van Reedt, D. A. K. B. et al. The impact of stress systems and lifestyle on dyslipidemia and obesity in anxiety and depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38, 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.05.017 (2013).

Nam, G. E. et al. Socioeconomic status and dyslipidemia in Korean adults: The 2008–2010 Korea National health and nutrition examination survey. Prev. Med. 57, 304–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.06.008 (2013).

Perk, J. E. et al. European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). The Fifth Joint task force of the European society of cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Eur. Heart J. 33(1635–1701), 2012. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs092 (2012).

Knutson, K. L., Van Cauter, E., Rathouz, P. J., DeLeire, T. & Lauderdale, D. S. Trends in the prevalence of short sleepers in the USA: 1975–2006. Sleep 33, 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/33.1.37 (2010).

Han, K. T. & Kim, S. J. Instability in daily life and depression: The impact of sleep variance between weekday and weekend in South Korean workers. Health Soc. Care Commun. 28, 874–882. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12918 (2020).

Watson, N. F. et al. Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: A joint consensus statement of the American academy of sleep medicine and sleep research society. Sleep 38, 843–844. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.4716 (2015).

Kang, S. G. et al. Weekend catch-up sleep is independently associated with suicide attempts and self-injury in Korean adolescents. Compr. Psychiatry 55, 319–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.08.023 (2014).

Kim, K. M. et al. Weekend catch-up sleep and depression: Results from a nationally representative sample in Korea. Sleep Med. 87, 62–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2021.02.058 (2021).

Åkerstedt, T. et al. Sleep duration and mortality-Does weekend sleep matter?. J. Sleep. Res. 28, e12712 (2019).

Tsiptsios, D. et al. Association between sleep insufficiency and dyslipidemia: A cross-sectional study among Greek adults in the primary care setting. Sleep Sci. 15, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.5935/1984-0063.20200124 (2022).

Kweon, S. et al. Data resource profile: The Korea national health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANES). Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt228 (2014).

Oh, Y. H., Kim, H., Kong, M., Oh, B. & Moon, J. H. Association between weekend catch-up sleep and health-related quality of life of Korean adults. Medicine 98, e14966. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000014966 (2019).

Rhee, E.-J. et al. 2018 guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia in Korea. JLA 8, 78–131. https://doi.org/10.12997/jla.2019.8.2.78 (2019).

Jeong, J.-S. & Kwon, H.-S. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of dyslipidemia in Koreans. ENM 32, 30–35. https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2017.32.1.30 (2017).

Kweon, S. et al. Data resource profile: The Korea national health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANES). Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 69–77 (2014).

Manocchia, M., Keller, S. & Ware, J. E. Sleep problems, health-related quality of life, work functioning and health care utilization among the chronically ill. Qual. Life Res. 10, 331–345. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1012299519637 (2001).

Dewald, J. F., Meijer, A. M., Oort, F. J., Kerkhof, G. A. & Bögels, S. M. The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 14, 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.004 (2010).

Gallicchio, L. & Kalesan, B. Sleep duration and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sleep Res. 18, 148–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00732.x (2009).

Hasler, B. P. et al. Weekend-weekday advances in sleep timing are associated with altered reward-related brain function in healthy adolescents. Biol. Psychol. 91, 334–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.08.008 (2012).

Cho, H. S. et al. The relationship between depressive symptoms among female workers and job stress and sleep quality. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 25, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/2052-4374-25-12 (2013).

Park, J. B., Nakata, A., Swanson, N. G. & Chun, H. Organizational factors associated with work-related sleep problems in a nationally representative sample of Korean workers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 86, 211–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-012-0759-3 (2013).

Roepke, S. E. & Duffy, J. F. Differential impact of chronotype on weekday and weekend sleep timing and duration. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2010, 213–220. https://doi.org/10.2147/nss.S12572 (2010).

Han, K.-M., Lee, H.-J., Kim, L. & Yoon, H.-K. Association between weekend catch-up sleep and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels in adults: A population-based study. Sleep 43, 87. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsaa010 (2020).

Im, H. J. et al. Association between weekend catch-up sleep and lower body mass: Population-based study. Sleep https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsx089 (2017).

Hwangbo, Y., Kim, W. J., Chu, M. K., Yun, C. H. & Yang, K. I. Association between weekend catch-up sleep duration and hypertension in Korean adults. Sleep Med. 14, 549–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2013.02.009 (2013).

Wang, C. et al. Association of estimated sleep duration and naps with mortality and cardiovascular events: A study of 116 632 people from 21 countries. Eur. Heart J. 40, 1620–1629. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy695 (2018).

Hoevenaar-Blom, M. P., Spijkerman, A. M., Kromhout, D. & Verschuren, W. M. Sufficient sleep duration contributes to lower cardiovascular disease risk in addition to four traditional lifestyle factors: The MORGEN study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 21, 1367–1375. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487313493057 (2020).

Seo, Y., Sung, G.-H., Lee, S. & Han, K. J. Weekend catch-up sleep is associated with the alleviation of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann. Hepatol. 27, 100690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aohep.2022.100690 (2022).

Joo, J. H., Lee, D. W., Choi, D.-W. & Park, E.-C. Association between night work and dyslipidemia in South Korean men and women: A cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis. 18, 75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-019-1020-9 (2019).

Wilkinson, R. T. How fast should the night shift rotate?. Ergonomics 35, 1425–1446. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139208967412 (1992).

Abreu, G. D. A., Barufaldi, L. A., Bloch, K. V. & Szklo, M. A systematic review on sleep duration and dyslipidemia in adolescents: Understanding inconsistencies. Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia 105, 418–425 (2015).

Lee, H., Kim, Y. J., Jeon, Y. H., Kim, S. H. & Park, E. C. Association of weekend catch-up sleep ratio and subjective sleep quality with depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among Korean adolescents. Sci. Rep. 12, 10235. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14352-1 (2022).

Grandner, M. A. & Drummond, S. P. Who are the long sleepers? Towards an understanding of the mortality relationship. Sleep Med. Rev. 11, 341–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2007.03.010 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2022R1F1A1062794).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S.J. made a substantial contribution to the concept or design of the work; Y.S.J., K,D,H and Y.S.P. contributed to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; Y.S.J., E.P., and S.-I.J. drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the version to be published and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the Acknowledgements section. Full information regarding the correction made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jang, Y.S., Park, Y.S., Hurh, K. et al. Association between weekend catch-up sleep and dyslipidemia among Korean workers. Sci Rep 13, 925 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28142-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28142-w

This article is cited by

-

Genetic study of the causal effect of lipid profiles on insomnia risk: a Mendelian randomization trial

BMC Medical Genomics (2023)

-

Associations between weekend catch-up sleep and health-related quality of life with focusing on gender differences

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Evaluation of weekend catch-up sleep and weekday sleep duration in relation to metabolic syndrome in Korean adults

Sleep and Breathing (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.