Abstract

The serological diagnostic criteria for the immune-tolerant (IT) phase have not been strictly defined and it is hard to determine an accurate rate for significant histologic changes among IT patients. The aim of this study was to establish a baseline rate of significant histologic changes and to determine the main characteristics of IT patients. We systematically searched PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science. Studies reporting liver biopsy results (inflammation grade or fibrosis stage) for adults with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in the IT phase diagnosed by serological criterion were included to pool the rate of significant histologic changes. Studies that enrolled subjects with confirmed chronic HBV infection in the IT phase diagnosed by serological and liver biopsy criteria (dual criteria) were included to pool the mean values of main characteristics among IT patients. Of 319 studies screened, 15 were eventually included in the meta-analysis. The pooled rates of significant liver fibrosis and inflammatory activity for 10 studies were 10% (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.06–0.18) and 16% (95% CI 0.07–0.31), respectively. The pooled mean values of age, alanine aminotransferase level, HBV DNA level, and HBsAg level for another 5 studies with IT patients diagnosed by dual criteria were 30.7 years (95% CI 27.31–34.09), 26.64 IU/mL (95% CI 24.45–28.83), 8.41 log10 cp/mL (95% CI 7.59–9.23), and 4.24 log10 IU/mL (95% CI 3.67–4.82), respectively. Significant histologic changes were not rare events among IT patients. Strictly defined serological diagnostic criteria for the IT phase are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains a serious global public health burden that affects approximately 240 million individuals worldwide and is the leading cause of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)—the third primary cause of cancer deaths globally1,2. Chronic HBV infection typically undergoes dynamic phases depending on the host’s immune response and HBV replication3. The immune-tolerant (IT) phase, which is the earliest phase of chronic HBV infection, is characterized by high serum HBV DNA level, persistently normal alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, and no or minimal liver disease4,5,6.

High HBV DNA level is a major driving force that leads to hepatitis, thus increasing the risk of cirrhosis and HCC in IT patients7,8. Some studies reported HBV DNA integration, clonal hepatocyte expansion, and even significant histologic changes during the so-called IT phase in young patients with chronic HBV infection, as defined by their serological profile9,10,11. Furthermore, an initial research from Korea showed that the risk of HCC and death/transplantation was higher in untreated IT patients (defined by serological profile) than in treated immune-active patients12. Thus, considerable controversy has surrounded the treatment for IT patients for a few years9,13,14,15,16.

Antiviral therapy for patients during the IT phase has not been recommended by most practice guidelines because disease progression including histologic necroinflammation or fibrosis is not active at this stage3,5,17. Throughout the natural history of chronic HBV infection, serum HBV DNA titer is the highest during the IT phase, and there exists an undercurrent surge of immune clearance and inflammatory activity within the normal ALT range18. Previous studies showed that the rate of significant fibrosis in the IT phase can range from 0 to 46.8%, which is affected by various patient characteristics such as age, serum HBV DNA level, and HBsAg level19,20. In addition, major international guidelines have not yet reached a consensus on these characteristics3,5,17.

Because significant histologic changes are affected by virus–host interaction and immune response, accurately determining the rate of significant histologic changes in IT patients is difficult. The establishment of a baseline rate of significant histologic changes in IT patients would be important and crucial for clinical decision and patients’ benefit. Hence, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to address this issue. Additionally, we calculated the pooled mean values of main clinical parameters among IT patients diagnosed by dual criteria to determine the characteristics of IT patients.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

This study is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42019125197). We systematically searched PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science from their inception to 1 October 2022 using a combination of search terms related to “chronic hepatitis B,” “immune tolerance,” and “liver biopsy.” Attempts were made to contact the corresponding authors for additional data. The references of all included studies were manually searched for additional eligible articles. The detailed search strategy is presented in Supplementary Methods.

Cross-sectional studies, observational cohort studies, and randomized controlled trials that reported liver biopsy results (inflammation grade or fibrosis stage) for adults with chronic HBV infection in the IT phase diagnosed by serological criterion were included to pool the rate of significant histologic changes. Studies that enrolled subjects with confirmed chronic HBV infection in the IT phase diagnosed by serological and liver biopsy criteria (dual criteria) were included to pool the mean values of main characteristics among IT patient.

The serological criterion for the IT phase was defined as high serum HBV DNA level (typically > 4.0 log10 IU/mL) and persistently normal (upper limit of normal [ULN] approximately 40 IU/mL). The liver biopsy criterion for the IT phase was defined as no or minimal liver disease (liver inflammation or fibrosis).

The following studies were excluded from the analysis: studies with a sample size of < 10 individuals; studies that included subjects with other overlapping causes of hepatitis and fibrosis, such as hepatitis C and hepatitis D; studies that included subjects co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus; studies that included subjects who had prior HCC, underwent liver transplantation, or received chemotherapy; pediatric studies, although we included studies enrolling subjects with age as low as 9 years; studies with insufficient data for extraction; case–control studies; and letters, reviews, posters, editorials, dissertations, and conference abstracts.

The diagnostic criteria for liver biopsy

The histological evaluation of the included studies consisted of Knodell system, Ishak system, Metavir system, Scheurer system, Batts-ludwig system and Chinese system. The diagnostic criteria for liver biopsy are based on different histological evaluation systems: (1) Knodell system21, where the hepatic activity index (HAI) was used to describe the hepatocellular necroinflammation activity with scores range from 0 to 22. HAI score ≥ 9 indicated significant inflammation, and HAI score 0–8 indicated no or minimal liver inflammation. (2) Ishak system22 of fibrosis, where the severity of fibrosis was graded from stage 0 to stage 6. Stage 0–2 indicated no or minimal liver fibrosis, and stage 3–6 indicated significant liver fibrosis. (3) Scheuer system23, where the severity of necroinflammation was graded from G0 to G4 and stage of fibrosis was graded from S0 to S4. S0–S1 indicated no or minimal liver fibrosis, and S2–S4 indicated significant liver fibrosis. G0–G1 indicated no or minimal liver inflammation, and G2–G4 indicated significant liver inflammation. (4) METAVIR system24, where the severity of necroinflammation was graded from A0 to A3 and stage of fibrosis was graded from F0 to F4. A0–A1 indicated no or minimal liver inflammation, and A2-A4 indicated significant liver inflammation. F0–F1 indicated no or minimal liver fibrosis, and F2–F4 indicated significant liver fibrosis. (5) Batts-Ludwig system25 and Chinese system26, which include five categories (0 to 4) separately for both inflammation grade and fibrosis stage. Grade 0–1 indicated no or minimal liver inflammation, and grade 2–4 indicated significant liver inflammation. Stage 0–1 indicated no or minimal liver fibrosis, and stage 2–4 indicated significant liver fibrosis.

Selection process and data extraction

Citations were merged in EndNote version X8 (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA) to facilitate management. Two reviewers independently examined the titles and abstracts in duplicate to identify potentially eligible studies and subsequently reviewed the full texts to identify studies in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We extracted data from the selected studies using a standardized form. Two data summary tables were prepared and compared for concordance. Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer. The following data were extracted from all eligible studies: first author, publication year, study location, study design, sample size, ULN for ALT, criteria for immune tolerance, sex, ALT level, age, HBV DNA titer, HBsAg level, standard for liver biopsy, and liver biopsy results.

Outcomes

The predetermined primary outcome was the rate of significant histologic changes among IT subjects. Significant histologic changes were defined as significant liver fibrosis or significant inflammatory activity on liver biopsy. The secondary outcome was the mean values of main characteristics among IT patients diagnosed by dual criteria.

Quality assessment

The Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale was used to evaluate the quality of included studies27. Studies were scored according to the following three items: patient selection (four stars), comparability of study groups (two stars), and assessment of outcome/exposure (three stars). With this scale (a maximum of nine stars), a score rating system was employed to indicate the quality of each study. Scores of 0–3, 4–6, and ≥ 7 signified poor, fair, and high quality, respectively.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the pooled rate of significant histologic changes among subjects in the IT phase using random-effects meta-analysis. In addition, we pooled the mean values of key clinical parameters (ALT level, age, HBV DNA level, and quantitative HBsAg level) among IT patients diagnosed by dual criteria. Cochran’s Q statistic (with heterogeneity < 0.10 suggesting statistical significance) and I2 statistic (with I2 > 75.0% representing substantial heterogeneity, 50.0% ≤ I2 ≤ 75.0% representing moderate heterogeneity, and I2 < 50% representing low heterogeneity) were adopted to qualitatively and quantitatively evaluate heterogeneity across studies, respectively.

Sources of heterogeneity were mainly investigated using subgroup analyses by stratifying preplanned variables, including study location, study type, mean age, and ALT level. Furthermore, a sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding studies that enrolled subjects aged < 18 years, studies with sample sizes of < 50 individuals, and studies that did not definitely define HBV DNA titer in IT patients. Publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot and Egger’s test28.

Statistical significance level was set at two-sided P < 0.05, unless otherwise specified. All statistical analyses were performed using the “meta” package of R software version 3.5.2 (R Software Foundation, Vienna, Austria). We used metaprop to pool the rate of significant histologic changes among IT patients and metamean to pool the mean values of main characteristics among IT patients diagnosed by dual criteria.

Results

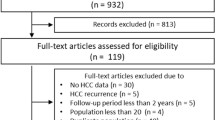

The selection process is shown in Fig. 1. The initial search yielded 319 records from the three databases. A total of 45 citations were thought to be potentially relevant after reviewing the titles and abstracts. Nevertheless, 33 citations were excluded after carefully reading the full texts. Three studies were considered eligible for inclusion in the hand-searching process. Finally, 15 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis19,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. These studies cumulatively reported 1,588 subjects.

Study characteristics and quality assessment

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. Among the included studies, 10 studies19,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,42 reported the rate of significant liver disease among IT patients according to the serological criterion, whereas the other 5 studies37,38,39,40,41 reported the mean values of main characteristics among IT patients diagnosed by dual criteria. The included studies were from 5 countries, with 13 studies conducted in Asia and the remaining studies conducted in France19 and the United States31. All of the included studies defined ALT level within the ULN in IT patients. The sample size of the included studies ranged from 10 to 455 subjects, with the proportion of males ranging from 21.6 to 83.3%. One study included subjects younger than 18 years of age29. The mean or median age and ALT level ranged from 18 to 39 years and from 21 to 33 IU/mL, respectively.

Ten studies reported events and rate of significant histologic changes on liver biopsy (Table 2). The staging and grading systems involved in these studies were the METAVIR system, Scheuer system, Batts–Ludwig system, Ishak fibrosis score, Knodell histology activity index, and Chinese system. The rates of significant liver fibrosis and inflammatory activity ranged from 0 to 31.8% and 59.8%, respectively. The overall rate of significant histologic changes was absent because most studies did not report the overall events. Quality assessment was performed on the 15 included studies, and no study showed high risk of bias (details shown in Supplementary Table 1).

Pooled rate of significant histologic changes

Of 1408 patients in 10 studies, 163 (11.6%) and 258 (18.3%) showed significant liver fibrosis and inflammatory activity. The pooled rates of significant liver fibrosis and inflammatory activity in these 10 studies were 10% (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.06–0.18, I2 = 83%; Fig. 2A) and 16% (95% CI 0.07–0.31, I2 = 95%; Fig. 2B), respectively.

Pooled mean values of main characteristics among IT patients diagnosed by dual criteria

In 180 patients from 5 studies, the pooled mean values of age, ALT level, HBV DNA level, and HBsAg level among IT patients diagnosed by dual criteria were 30.7 years (95% CI 27.31–34.09, I2 = 90%), 26.64 IU/mL (95% CI 24.45–28.83, I2 = 70%), 8.41 log10 cp/mL (95% CI 7.59–9.23, I2 = 99%), and 4.24 log10 IU/mL (95% CI 3.67–4.82, I2 = 99%), respectively (Fig. 3).

Rate of significant histologic changes according to baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

The pooled rate of significant liver fibrosis for Asia and Western countries was 11% (95% CI 0.07–0.17) and 3% (95% CI 0.00–0.85), respectively, albeit without statistically significant difference (Table 3). The mean age in 9 studies19,29,30,31,32,34,35,36,42 was 32 years, and the pooled rate of significant liver fibrosis was similar between studies that included subjects with a mean age of < 32 years (11%; 95% CI 0.04–0.25) and studies that included subjects with a mean age of > 32 years (13%; 95% 0.08–0.22), albeit without statistically significant difference. The mean ALT level in 8 studies19,30,31,32,34,35,36,42 was 26 IU/mL, and the pooled rate of significant liver fibrosis for studies with ALT level < 26 IU/mL (8%; 95% CI 0.02–0.25) was slightly lower than that for studies with ALT level > 26 IU/mL (16%; 95% CI 0.09–0.26), albeit without statistically significant difference.

The pooled rate of significant inflammatory activity was slightly higher for Asia (17%; 95% CI 0.07–0.35) than for Western countries (13%; 95% CI 0.03–0.37), albeit without statistically significant difference. The pooled rate of significant inflammatory activity for studies that included subjects with a mean age of < 32 years (9%; 95% CI 0.02–0.33) was a little lower than that for studies with a mean age of > 32 years (16%; 95% CI 0.08–0.30), albeit without statistically significant difference. The pooled rate of significant inflammatory activity for studies with ALT level < 26 IU/mL (9%; 95% CI 0.03–0.22) was lower than that for studies with ALT level > 26 IU/mL (13%; 95% CI 0.05–0.30), albeit without statistically significant difference.

Analysis of study type was not performed because of a lack of primary data. There were no publication biases in the meta-analysis of the rates of significant liver fibrosis and inflammatory activity according to the funnel plot (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2) using Egger’s test (P = 0.66 and 0.71, respectively).

Sensitivity analysis

We performed 3 sensitivity tests for 10 studies (Supplementary Figs. 3–5). In the first sensitivity test in which studies that enrolled subjects aged < 18 years were excluded, the pooled rate of significant liver fibrosis remained the same (10%; 95% CI 0.05–0.19, I2 = 85%), whereas the pooled rate of significant inflammatory activity slightly lowered (14%; 95% CI 0.06–0.28, I2 = 95%). Nonetheless, heterogeneity remained high. In the second sensitivity test, we excluded studies that did not definitely define HBV DNA titer in IT patients. The pooled rate of significant liver fibrosis remained the same at 10% (95% CI 0.09–0.12, I2 = 48%) with moderate heterogeneity. The pooled rate of significant inflammatory activity remained similar at 15% (95% CI 0.08–0.28, I2 = 92%) with high heterogeneity. Finally, we excluded studies with sample sizes of < 50 individuals. For the remaining studies, the pooled rate of significant liver fibrosis remained the same (10%; 95% CI 0.06–0.18, I2 = 89%), whereas the pooled rate of significant inflammatory activity became higher (25%; 95% CI 0.12–0.44, I2 = 97%), respectively. Nonetheless, heterogeneity remained high.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first systematic effort to evaluate the rate of significant histologic changes among IT patients. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we determined that the pooled rates of significant liver fibrosis and inflammatory activity were 10% and 16%, respectively. Significant histologic changes are not rare events among IT patients. Our finding is in agreement with that of a large-scale prospective multicenter study35, in which the rates of significant liver fibrosis and inflammatory activity were 9.4% and 17.4%, respectively. However, the substantial heterogeneity of our results requires that they should be interpreted with caution.

The pooled rates of significant liver fibrosis and inflammatory activity were higher in Asia than in Western countries, albeit without statistically significant difference. This could have resulted from the limited study size and quantity in Western countries and the high prevalence of HBV infection in Asia, which accounted for more than 57% of all HBsAg-positive infections43. The American practice guideline has recommended lower ALT levels to define the IT phase5. Along with the findings of others30,34, our analysis confirmed that a lower ALT level could predict a lower rate of significant histologic changes, albeit without statistically significant difference in our study.

It is well known that younger IT patients generally have high HBV DNA titer and show minimal hepatitis activity15. The subgroup analysis of age in our study revealed that younger patients were less likely to have significant liver fibrosis and significant inflammatory activity. This result was similar to the finding of the study35 mentioned above, which performed univariate analysis of factors and histologic disease. In this previous study, younger patients were less likely to develop significant liver fibrosis and inflammatory activity, though significant difference in significant inflammatory activity was not observed35.

By combining the data of IT patients diagnosed by dual criteria, we determined the main characteristics of IT patients. The pooled mean values of age, ALT level, HBV DNA level, and HBsAg level were 30.7 years, 26.64 IU/mL, 8.41 log10 cp/mL, and 4.24 log10 IU/mL, respectively, which were consistent with the definition of IT in most practice guidelines3,5,17. Although our study indicated a mean age of 30.7 years, IT loss often occurs at a mean age of 30–35 years (40 years in 90% of individuals)4. In a French study that defined HBV DNA titer of more than 107 cp/mL among IT patients, liver biopsy showed extremely low histologic disease rate19. The pooled mean HBV DNA value in our study further shows that we need to strictly define HBV DNA titer in the IT phase to avoid the unnecessary performance of liver biopsy44. Similar to other studies, our study indicated that a high HBsAg level (typically > 4.0 log10 IU/mL) is also an important feature of the IT phase45,46,47.

Our study has some limitations that warrant attention. First, serological diagnostic criteria for the IT phase in the included studies, especially HBV DNA, were not uniform, which would affect the rate of significant histologic changes. Major international guidelines have not reached a consensus on serological diagnostic criteria for the IT phase3,5,17. For instance, the American practice guideline has recommended a very high HBV DNA level (typically > 106 IU/mL) to define the IT phase, whereas the recent European and Asian–Pacific practice guideline has recommended an HBV DNA level > 107 IU/mL; furthermore, the Chinese practice guideline recommended a very high HBV DNA level (typically > 105 IU/mL)3,17,48. In our study, most of the included studies defined a high HBV DNA level for IT patients, but we performed sensitivity analysis of only studies with definitely define HBV DNA titer in IT patients and found a similar pooled estimate as the main result.

Second, there was insufficient diversity in represented countries, particularly in Asia. Studies from China accounted for more than half of all included studies, and most studies were from Asia. According to a recent study, Asian countries have a high prevalence of HBV infection. Moreover, limited cases were included in our study. This could be because liver biopsy is an invasive examination that is difficult for subjects to accept. Noninvasive methods for the assessment of liver fibrosis such as liver stiffness measurements prove to be excellent with respect to performance and are widely available49,50. However, data on noninvasive methods for IT patients are still not available. Finally, the pooled mean values of main characteristics and pooled rates of significant liver fibrosis and inflammatory activity should be interpreted with caution because of high heterogeneity, despite our attempt to reduce it using subgroup and sensitivity analysis.

Conclusion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we determined that significant histologic changes were not rare events among IT patients. Strictly defined serological diagnostic criteria for the IT phase are warranted to avoid the occurrence of significant histologic changes during this period.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the paper and its Supplementary Information, or from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Bertuccio, P. et al. Global trends and predictions in hepatocellular carcinoma mortality. J. Hepatol. 67, 302–309 (2017).

Schweitzer, A., Horn, J., Mikolajczyk, R. T., Krause, G. & Ott, J. J. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: A systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet 386, 1546–1555 (2015).

EASL. Clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J. Hepatol. 2017(67), 370–398 (2017).

Liaw, Y. F. & Chu, C. M. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet 373, 582–592 (2009).

Terrault, N. A. et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology 67, 1560–1599 (2018).

Sarin, S. K. & Kumar, M. Should chronic HBV infected patients with normal ALT treated: Debate. Hepatol. Int. 2, 179–184 (2008).

Chen, C. J. et al. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA 295, 65–73 (2006).

Iloeje, U. H. et al. Predicting cirrhosis risk based on the level of circulating hepatitis B viral load. Gastroenterology 130, 678–686 (2006).

Mason, W. S. et al. HBV DNA integration and clonal hepatocyte expansion in chronic hepatitis b patients considered immune tolerant. Gastroenterology 151, 986-998.e984 (2016).

Tu, T. et al. Clonal expansion of hepatocytes with a selective advantage occurs during all stages of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J. Viral. Hepat. 22, 737–753 (2015).

Nguyen, M. H. et al. Histological disease in Asian-Americans with chronic hepatitis B, high hepatitis B virus DNA, and normal alanine aminotransferase levels. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 104, 2206–2213 (2009).

Kim, G. A. et al. High risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and death in patients with immune-tolerant-phase chronic hepatitis B. Gut 67, 945–952 (2018).

Milich, D. R. The concept of immune tolerance in chronic hepatitis B virus infection is alive and well. Gastroenterology 151, 801–804 (2016).

Protzer, U. & Knolle, P. “To be or not to be”: Immune tolerance in chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 151, 805–806 (2016).

Liaw, Y. F. & Chu, C. M. Immune tolerance phase of chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 152, 1245–1246 (2017).

Tseng, T. C. & Kao, J. H. Treating immune-tolerant hepatitis B. J. Viral Hepat. 22, 77–84 (2015).

Sarin, S. K. et al. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B: A 2015 update. Hepatol. Int. 10, 1–98 (2016).

Tseng, T. C. & Kao, J. H. Clinical utility of quantitative HBsAg in natural history and nucleos(t)ide analogue treatment of chronic hepatitis B: New trick of old dog. J. Gastroenterol. 48, 13–21 (2013).

Andreani, T. et al. Chronic hepatitis B virus carriers in the immunotolerant phase of infection: histologic findings and outcome. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5, 636–641 (2007).

Zhang, Z. Q. et al. Distinct patterns of serum hepatitis B core-related antigen during the natural history of chronic hepatitis B. BMC Gastroenterol. 17, 140 (2017).

Knodell, R. G. et al. Formulation and application of a numerical scoring system for assessing histological activity in asymptomatic chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology 1, 431–435 (1981).

Ishak, K. et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 22, 696–699 (1995).

Scheuer, P. J. Classification of chronic viral hepatitis: A need for reassessment. J. Hepatol. 13, 372–374 (1991).

The French METAVIR Cooperative Study Group. Intraobserver and interobserver variations in liver biopsy interpretation in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 20, 15–20 (1994).

Batts, K. P. & Ludwig, J. Chronic hepatitis: An update on terminology and reporting. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 19, 1409–1417 (1995).

Wang, T. L. et al. Scoring scheme for inflammatory activity and fibrosis degree of chronic hepatitis. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 6, 195–197 (1998).

Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 25, 603–605 (2010).

Egger, M., Davey Smith, G., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315, 629–634 (1997).

Li, J., Zhao, G. M., Zhu, L. M., Li, Y. & Xin, S. J. Liver pathological changes and clinical features of patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection in their immune tolerant phase and non-active status. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 15, 326–329 (2007).

Park, J. Y. et al. High prevalence of significant histology in asymptomatic chronic hepatitis B patients with genotype C and high serum HBV DNA levels. J. Viral Hepat. 15, 615–621 (2008).

Wang, C. C. et al. Factors predictive of significant hepatic fibrosis in adults with chronic hepatitis B and normal serum ALT. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 42, 820–826 (2008).

Wan, R. J. et al. Noninvasive predictive models of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 8, 961–971 (2015).

Wu, J. Z., Huang, R. G. & Yang, X. X. Differences in HbsAg and HbcAg expression in liver tissues between chronic hepatitis B patients with immunologic tolerance vs immune activity. World Chin. J. Digestol. 25, 620–626 (2017).

Liu, H. Y. et al. Differentially expressed intrahepatic genes contribute to control of hepatitis B virus replication in the inactive carrier phase. J. Infect. Dis. 217, 1044–1054 (2018).

Xing, Y. F. et al. Clinical and histopathological features of chronic hepatitis B virus infected patients with high HBV-DNA viral load and normal alanine aminotransferase level: A multicentre-based study in China. PLoS ONE 13, e0203220 (2018).

Zhang, P. et al. Serum hepatitis B surface antigen correlates with fibrosis and necroinflammation: A multicentre perspective in China. J. Viral Hepat. 25, 1017–1025 (2018).

Hui, C. K. et al. Natural history and disease progression in Chinese chronic hepatitis B patients in immune-tolerant phase. Hepatology 46, 395–401 (2007).

Li, W. J. et al. Analysis of hepatitis B virus intrahepatic covalently closed circular DNA and serum viral markers in treatment-naive patients with acute and chronic HBV infection. PLoS ONE 9, e89046 (2014).

Chen, E. Q. et al. Serum hepatitis B core-related antigen is a satisfactory surrogate marker of intrahepatic covalently closed circular DNA in chronic hepatitis B. Sci. Rep. 7, 173 (2017).

Singh, A. K. et al. Global microRNA expression profiling in the liver biopsies of hepatitis B virus-infected patients suggests specific microRNA signatures for viral persistence and hepatocellular injury. Hepatology 67, 1695–1709 (2018).

Wang, J. et al. Natural history of serum HBV-RNA in chronic HBV infection. J. Viral Hepat. 25, 1038–1047 (2018).

Hu, A. R. et al. Clinicopathological analysis in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection in immune tolerant phase. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi 60, 891–897 (2021).

Polaris Observatory Collaborators. Global prevalence, treatment, and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in 2016: A modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 3, 383–403 (2018).

Andreani, T., Serfaty, L., Poupon, R. & Chazouilleres, O. Need to strictly define hepatitis B virus immunotolerant patients to avoid unnecessary liver biopsy. Gastroenterology 135, 2155–2156 (2008).

Martinot-Peignoux, M., Lapalus, M., Asselah, T. & Marcellin, P. HBsAg quantification: Useful for monitoring natural history and treatment outcome. Liver Int. 34(Suppl 1), 97–107 (2014).

Nguyen, T. et al. Hepatitis B surface antigen levels during the natural history of chronic hepatitis B: A perspective on Asia. J. Hepatol. 52, 508–513 (2010).

Jaroszewicz, J. et al. Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) levels in the natural history of hepatitis B virus (HBV)-infection: A European perspective. J. Hepatol. 52, 514–522 (2010).

Wang, G. Q. et al. The guideline of prevention and treatment for chronic hepatitis B (a 2015 update). Chin. J. Liver Dis 7, 1-18. (2015).

Seto, W. K. & Yuen, M. F. Viral hepatitis: “Immune tolerance” in HBV infection: danger lurks. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 13, 627–628 (2016).

Conti, F. et al. Assessment of liver fibrosis with elastography point quantification vs other noninvasive methods. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17, 510–517 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Jian-ping Liu (Centre for Evidence-Based Chinese Medicine, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China) for his advice concerning the methodology of the study. Editage [www.editage.cn] provided assistance with English language editing.

Funding

Supported by China National Science and Technology major projects 13th 5-year plan (No. 2018ZX10725-505).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and Design—Z.G.L. and Y.A.Y.; Data Collection and Processing—Y.G., Z.G.L.; Analysis—D.L.Y., S.S. and Y.G.; Critical Review—Y.A.Y., Q.L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Yang, D., Ge, Y. et al. Histologic changes in immune-tolerant patients with chronic hepatitis B: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 13, 469 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-27545-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-27545-z

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.