Abstract

Tinnitus, a phantom perception of sound in the absence of any external sound source, is a prevalent health condition often accompanied by psychiatric comorbidities. Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) highlighted a polygenic nature of tinnitus susceptibility. A shared genetic component between tinnitus and psychiatric conditions remains elusive. Here we present a GWAS using the UK Biobank to investigate the genetic processes linked to tinnitus and tinnitus-related distress, followed by gene-set enrichment analyses. The UK Biobank sample comprised 132,438 individuals with tinnitus and genotype data. Among the study sample, 38,525 individuals reported tinnitus, and 26,889 participants mentioned they experienced tinnitus-related distress in daily living. The genome-wide association analyses were conducted on tinnitus and tinnitus-related distress. We conducted enrichment analyses using FUMA to further understand the genetic processes linked to tinnitus and tinnitus-related distress. A genome-wide significant locus (lead SNP: rs71595470) for tinnitus was obtained in the vicinity of GPM6A. Nineteen independent loci reached suggestive association with tinnitus. Fifteen independent loci reached suggestive association with tinnitus-related distress. The enrichment analysis revealed a shared genetic component between tinnitus and psychiatric traits, such as bipolar disorder, feeling worried, cognitive ability, fast beta electroencephalogram, and sensation seeking. Metabolic, cardiovascular, hematological, and pharmacological gene sets revealed a significant association with tinnitus. Anxiety and stress-related gene sets revealed a significant association with tinnitus-related distress. The GWAS signals for tinnitus were enriched in the hippocampus and cortex, and for tinnitus-related distress were enriched in the brain and spinal cord. This study provides novel insights into genetic processes associated with tinnitus and tinnitus-related distress and demonstrates a shared genetic component underlying tinnitus and psychiatric conditions. Further collaborative attempts are necessary to identify genetic components underlying the phenotypic heterogeneity in tinnitus and provide biological insight into the etiology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tinnitus is a phantom perception of sound in the absence of any external sound source. About 21 million US adults have experienced bothersome tinnitus, with 27% of tinnitus sufferers reporting symptoms for longer than 15 years1. About 2 million US adults experience an extreme form of debilitating tinnitus2. Individuals with debilitating tinnitus experience a severe manifestation of tinnitus-related distress in daily living, often characterized by chronic insomnia, inability to concentrate and relax, persistent anxiety and depression, and severe hyperacusis (heightened reaction to routine sounds)3. Tinnitus is a common hearing health concern among individuals exposed to intense noise4,5. About 15% of workers exposed to occupational noise experience bothersome tinnitus. Nearly 40% of workers with tinnitus believe that their tinnitus adversely affects their work, and 25% do not prefer to discuss their problems with others due to fear that it might affect their employment opportunities5. Personal economic loss to an individual with tinnitus can be up to $30,000/year, and the burden to society can be $26 billion/year3.

Tinnitus is a common hearing health concern in individuals with hearing loss (e.g.,6). Past studies suggest cochlear deafferentation can play a role in triggering tinnitus perception7. While peripheral cochlear damage and maladaptive central compensation are associated with tinnitus genesis, tinnitus-related distress is associated with altered cortical networks8. Several non-auditory structures such as the amygdala, hippocampus, middle and superior frontal gyri, cingulate gyrus, precuneus, and the parietal cortices are also associated with tinnitus9. Systematic diseases, such as hypertension and diabetes, can affect tinnitus perception (e.g.,10). Psychological factors, such as stress, anxiety, and depression, can also modify tinnitus perception11. Collectively, this multi-layered pathological mechanism can influence the phenotypic spectrum of tinnitus.

Recreational and occupational noise exposure is associated with tinnitus in large-scale epidemiological studies1,2,3,4,12. Smoking, ototoxic medications, and chemical exposure are significant risk factors for tinnitus1,2,3,4,13. Cardiovascular conditions such as hypertension, heart diseases, stroke, ischemia, and arterial hypertension are associated with tinnitus14. Common medical drugs for treating cardiovascular conditions, such as diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and calcium channel blockers, are associated with tinnitus15. Tinnitus is often accompanied by psychiatric conditions such as anxiety, depression, and bipolar disorder16. A Mendelian randomization study using the UK Biobank database identified hearing loss, major depression, neuroticism, and high systolic blood pressure associated with tinnitus17.

The genetic interrogation of tinnitus can help identify the underlying molecular mechanisms. Twin studies suggested a genetic component to tinnitus susceptibility. Tinnitus heritability (h2) ranges from 0.21 to 0.6818,19,20,21. The heritability estimate is about 0.68 for bilateral tinnitus in men and 0.41 in females21. Past genetic studies investigating tinnitus in a candidate gene set had limited success in identifying novel genetic variants involved in tinnitus (e.g.,22). Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are beginning to illuminate the polygenic nature of tinnitus susceptibility23,24,25,26,27. Two previous GWAS used the UK Biobank database to investigate the genetic variants underlying tinnitus. Clifford et al. identified six genome-wide significant loci associated with tinnitus in the UK Biobank cohort and replicated three of them in the Million Veteran Program cohort23. A recent study using the case–control approach with the UK Biobank database identified three variants in the vicinity of RCOR1 gene24. Here we conduct a complimentary GWAS analysis in the UK Biobank, adjusting for known environmental risk factors, and interrogating the genetic underpinnings of tinnitus-related distress. In addition, we conduct enrichment analyses to further understand the genetic processes linked to tinnitus and tinnitus-related distress. We find that gene sets specifically expressed in the central nervous system and underpinning neuropsychiatric disorders are enriched in GWAS significant loci for both tinnitus and tinnitus-related distress.

Methods

The ethical approval for the present study was obtained from the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board. The UK Biobank approved the research application, and the research was conducted per the UK Biobank regulations and guidelines. The informed consent was taken from all study participants. The UK Biobank database containing the demographic variables, questionnaire responses, and genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers were obtained (Project ID: 68779). The database includes data from > 500,000 participants assessed across the UK from 2006 to 2010. The volunteers donated blood samples while visiting a UK Biobank assessment center. The complete details of the blood sample collection and DNA extraction process are described earlier28.

Tinnitus phenotype and questionnaire responses

The participants filled out a touchscreen questionnaire at the UK Biobank assessment center. The question (Data-filed #4803) text was, “Do you get or have you had noises (such as ringing or buzzing) in your head or in one or both ears that last for more than five minutes at a time?”. The answer choice included, “Yes, now most or all of the time”, “Yes, now a lot of the time”, “Yes, now some of the time”, “Yes, but not now, but had in the past”, “No, never”, “Do not know”, and “Prefer not to answer”. We removed individuals answering, “Do not know” and “Prefer not to answer” from the study sample and created an ordinal variable with four levels—“No, never”, “Yes, but not now”, “Yes, now some of the time”, “Yes, now a lot of the time”.

Individuals reporting tinnitus were further questioned about tinnitus-related distress with (Data-filed #4814), “How much do these noises worry, annoy, or upset you when they are at their worst?”. The answer choices included “Severely”, “Moderately”, “Slightly”, “Not at all”, “Do not know”, and “Prefer not to answer”. We removed individuals answering, “Do not know” and “Prefer not to answer” from the study sample. We created an ordinal variable of five levels—“No, never (from Data-filed #4803)”, “Not at all”, “Slightly”, “Moderately”, and “Severely”. We reasoned individuals with no tinnitus would not experience tinnitus-related distress.

The questionnaire responses were used for evaluating potential confounders and covariates. The demographic variables such as age, sex, and ethnicity were extracted from the database. Occupational noise exposure was investigated by (Data-field #4825), “Have you ever worked in a noisy place where you had to shout to be heard?”. Recreational noise exposure was evaluated by (Data-field #4836), “Have you ever listened to music for more than 3 h per week at a volume which you would need to shout to be heard or, if wearing headphones, someone else would need to shout for you to hear them?”. The response choices for both questions included, “Yes, for more than 5 years”, “Yes, for around 1–5 years”, “Yes, for less than a year?”, “No”, “Do not know”, and “Prefer not to answer”.

Genome-wide association study (GWAS)

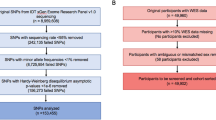

The genotyping was performed using two arrays, the Affymetric UK BiLEVE Axiom and Affymetric UK Biobank Axiom array. About 50,000 samples were genotyped on the Affymetric UK BiLEVE Axiom platform and 450,000 on the UK Biobank Axiom array. The genotypes were augmented by imputation using the Haplotype Reference Consortium29. Outliers with high heterozygosity or missingness were excluded29. Individuals of self-reported “White British” ancestry and similar genetic ancestry based on principal components were retained for GWAS analysis29. GWAS analysis was performed using REGENIE using age, sex, age^2, age × sex, the first 10 principal components, genotype batch, and testing site as covariates29,30. An additional study was done using two additional environmental covariates: loud music exposure frequency (#4836) and noisy workplace (#4725), both encoded as ordinal variables.

We identified 168,259 participants responding to the tinnitus question (#4803) after removing those with “do not know” and “prefer not to answer”. We included participants reporting British and Irish white ethnicity, which resulted in the exclusion of 21,116 participants. We excluded 2852 participants reporting “do not know” and “prefer not to answer” for the noisy workplace (#4825) and loud music exposure (#4836) questions. Related individuals were filtered out by excluding one individual in each pair of individuals with a kinship coefficient of greater than 0.0844 (greater than third-degree relationships). The remaining sample (N = 132,438) with non-missing phenotype and quality-controlled genotype data was used for further analysis.

The following filters were applied on genotype and imputed data: a minor allele frequency of > 0.5%, a genotyping rate of 99%, a minor allele count of > 5, a Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test p < 10–15, not present in low-present in the low complexity regions, and not involved in the inter-chromosomal LD. For step 1 in the REGENIE, UKB inter-chromosome LD and low-complexity regions were filtered out using the ‘—exclude’ flag. We applied LD pruning (R2 = 0.9, window size = 1000, step size = 100) on directly genotyped SNPs, and a total of 471,734 SNP markers were used for step 1. Sex, genotype batch, and testing site were listed as categorical covariates using the “—catCovarList” flag. The size of genotype blocks was set to 1000 for step 1 and 400 for step 2. In step 2, an approximation for the firth correction was used for p-values less than 0.01 using the “—firth” and “—approx” flags. Step 2 was performed on 8,357,671 imputed genetic variants achieving quality control. The p-value threshold of 5 × 10–8 was used to identify genetic associations with tinnitus phenotypes.

Pathway enrichment analysis was performed with FUMA31 with the following settings: Maximum p-value cutoff of lead SNPs of 1e-5; Maximum p-value cutoff of 1e−4; r2 threshold to define independent significant SNPs of 0.8; second R2 threshold to define independent significant SNPs of 0.1; UKB release2b 10 k White British for the reference panel population; maximum distance between LD blocks to merge into a locus of 250 kb; distance to genes or functional consequences of SNPs on genes to map of 100 kb. The gene-based analysis was performed using MAGMA (within FUMA). For the gene-based MAGMA analysis, a gene window of 50 kb upstream and 40 kb downstream was used. Otherwise, all settings were left as default. The multiple test correction was performed using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure per data source tested gene sets, and adjusted p < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant association.

Results

Table 1 presents the demographic details of the sample. In a sample of 132,438 participants with the complete phenotype and genotype data, 38,525 individuals (29.1%) reported any form of tinnitus. Among individuals with tinnitus, 8720 (6.6%) reported they experience tinnitus “most or all of the time”, 3347 (2.5%) reported tinnitus “now a lot of the time”, 11,816 (8.9%) reported tinnitus for “now some of the time”, and 14,642 (11%) reported, “not now, but had in the past”. 93,913 individuals (70.9%) reported no tinnitus experience lasting five minutes or more at a time. Table 1 presents the prevalence of tinnitus with sex, ethnicity, music exposure, noise exposure, and testing sites. The study sample included 61,646 (46.5%) males and 70,792 (53.5%) females. The prevalence of any form of tinnitus was higher in males than females (OR = 0.75, 95%CI = 0.73–0.76, p < 10–123). The prevalence of “most or all of the time” tinnitus perception was also higher in males than females (OR = 0.51, 95%CI 0.49–0.53, p < 10–10). Individuals with music exposure (OR = 1.88, 95%CI 1.82–1.92, p < 10–10) and work-related noise exposure (OR = 2.14, 95%CI 2.08–2.20, p < 10–10) showed a significantly higher prevalence of any form of tinnitus than their counterparts.

Table 2 presents the prevalence of tinnitus-related distress across the study sample. The study sample included 1211 individuals (0.9% of the overall sample) reporting they were severely annoyed, worried, or upset due to their tinnitus perception. While 6278 (4.8%) reported they were moderate, 18,400 (14%) were slight, and 12,362 (9.3%) were not at all annoyed, worried, or upset due to their tinnitus perception. We compared the prevalence of individuals reporting significant tinnitus-related distress (those who reported “slightly”, “moderately”, and “severely”) and those without tinnitus-related distress. Females reported a significantly higher prevalence of tinnitus-related distress than males (OR = 1.38, 95%CI 1.32–1.44, p < 10–10). Noise exposure (OR = 0.98, 95%CI 0.94–1.03, p = 0.59) did not show a significant association with tinnitus-related distress (OR = 0.98, 95%CI 0.94–1.03, p = 0.59), and music exposure revealed a weak association (OR = 0.92, 95%CI 0.87–0.98, p = 0.009). Therefore, we did not include them as covariates for the GWAS investigating tinnitus-related distress.

GWAS results for tinnitus

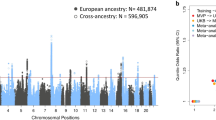

Figure 1 presents a Manhattan plot for tinnitus, and Table 3 shows the lead SNPs achieving genome-wide suggestive significance of p-value < 10–6. The GWAS identified one locus, with a lead SNP rs71595470, in the proximity to GPM6A, reaching the genome-wide significance with the p-value of 2.48E-8 (Fig. 2, Table 3, Supplementary File S1) (Genomic Control λ = 1.12). Another SNP, rs75074056, in proximity to rs71595470, achieved genome-wide significance (Fig. 2). Nineteen independent loci reached suggestive significance (Table 3). The major genes within or near the associated loci are listed in Table 3. Gene-based testing of SNPs summary statistic data identified PSAP and TNRC6 were significantly associated with tinnitus (Supplementary File S1).

FUMA enrichment analysis for tinnitus

We obtained significant results for positional gene sets, transcription factor targets gene sets, and GWAS catalog reported genes (Supplementary File S2). Twenty-three GWAS catalog gene sets revealed a significant association with tinnitus. The significant GWAS catalog gene sets associated with tinnitus included psychiatric and psychological traits, such as bipolar disorder, feeling worried, cognitive ability, fast beta electroencephalogram, and sensation seeking. Metabolic traits, such as wait-to-hip ratio adjusted for BMI, showed significant association with tinnitus. The gene set related to cardiovascular traits, such as hypertension, ischemic stroke, mean arterial pressure, stroke, systolic and diastolic blood pressure (main effect and interaction with smoking and alcohol), and plateletcrit showed significant association with tinnitus. Gene sets related to diuretics, metformin, fenofibrate, and TNF inhibitor used for rheumatoid arthritis showed association with tinnitus. The enrichment analysis for differentially expressed genes revealed that the GWAS signals were enriched in genes upregulated in the brain hippocampus (differentially expressed genes-two-sided adjusted p-value = 0.006, differentially expressed genes-upregulated adjusted p-value = 0.046) and cortex (differentially expressed genes-upregulated adjusted p-value = 0.015). (Supplementary Files S1–S2).

GWAS results for tinnitus-related distress

Figure 3 presents a Manhattan plot for tinnitus-related distress, and Table 4 shows the SNPs achieving the suggestive significance. Fifteen independent loci showed suggestive association with tinnitus-related distress (Genomic Control λ = 1.10). However, none of the tested SNPs achieved genome-wide significance. A SNP (rs28600198) in a non-coding RNA gene (snoU13 on Chromosome 4), achieved the lowest p-value (Fig. 4). The gene-based test showed a significant association between PSAP and tinnitus-related distress (Supplementary File S1).

FUMA enrichment analysis for tinnitus-related distress

The GWAS catalog gene sets related to anxiety and stress-related disorders showed four (out of 15) overlapping genes with the tinnitus gene set. Heel bone mineral density, cutaneous systemic scleroderma, molar-incisor hypomineralization, and lumbar disc degeneration showed significantly overlapped genes with tinnitus. The GWAS signals were enriched in genes differentially expressed in the brain and spinal cord (cervical c-1) (differentially expressed genes-upregulated adjusted p-value = 0.039). (Supplementary Files S1 and S3).

Discussion

The present study conducted a genome-wide association analysis to identify SNPs associated with tinnitus and tinnitus-related distress using the UK Biobank database. A SNP close to GPM6A achieved genome-wide significance, and 19 independent genetic loci showed suggestive association with tinnitus. Tinnitus-related distress showed suggestive association with 15 independent genomic loci. The gene-based test identified PSAP was associated with tinnitus and tinnitus-related distress, and TNRC6 was associated with tinnitus. The enrichment analysis identified psychiatric, cardiovascular, metabolic, hematological, and pharmacogenomic genomic signatures associated with tinnitus and tinnitus-related distress. The differential gene expression enrichment analysis revealed that the GWAS signals for tinnitus were enriched in genes upregulated in the hippocampus and cortex. They were enriched in genes differentially expressed in the brain and spinal cord for tinnitus-related distress (cervical c-1). Table 5 presents the summary statistics for SNPs associated with tinnitus by Wells et al. and Clifford et al.23,24. The differences in the results could be attributed to the sample selection criteria and GWAS methods.

Tissue-specific enrichment of the GWAS signals in the hippocampus and cortex

The interplay between auditory and non-auditory structures following traumatic events such as noise exposure plays an essential role in tinnitus perception32. In epidemiological studies, traumatic noise and music exposure are consistently associated with tinnitus1,2,3,12. Noise-induced cochlear deafferentation and hyperactivity in the central auditory pathway were studied as putative mechanisms underlying tinnitus perception33. Past studies concluded that hyperactivity in the auditory structure plays a crucial role in tinnitus perception. In contrast, the role of the non-classical auditory structures is limited to regulating tinnitus-related distress33. However, recent studies highlighted the critical role of the non-auditory structures, such as the hippocampus, amygdala, and cingulate cortex, in generating and maintaining tinnitus perception32,34. The amygdala and hippocampus receive input from the medial geniculate body in the thalamus and can interact with the auditory pathway (e.g.,35). The failure to inhibit the hyperactivity generated in the auditory pathway by non-classical auditory structures (such as the limbic system) is a putative mechanism underlying tinnitus perception36. Consistent with this hypothesis, recent neuroimaging studies indicate that the hippocampus and parahippocampus in the limbic system are associated with tinnitus (e.g.,37). The enrichment of the GWAS signals in the hippocampus and cortex observed in the present study (Supplementary File S1) highlighted their importance in tinnitus perception.

SNPs associated with tinnitus and tinnitus-related distress

GPM6A is the closest gene to the genomic region, with a lead SNP rs71595470 achieving genome-wide significance (Fig. 2). SNPs (rs183819925 and rs76744071) in the vicinity of the region were associated with a cognitive decline rate38. Several SNPs in GPM6A body revealed association with cognitive ability (rs13136969, rs6553899), schizophrenia (rs7673823, rs13142920, rs62334820, rs2333321, rs1106568; rs6846161), depression (rs6818081), neuroticism (rs72704531, rs17611770), and educational attainment (rs1814701, rs17598675, rs4146675)39,40. Tinnitus often accompanies psychiatric comorbidities such as anxiety, depression, cognitive dysfunction, and suicidal thoughts41,42. The genomic region containing a lead SNP in the vicinity of GPM6A might lie at the crossroad between tinnitus and psychiatric comorbidities.

GPM6A is a protein coding gene belonging to the tetraspan proteolipid protein family that encodes neural glycoprotein M6a43,44. GPM6A plays an essential role in neural growth by functioning as an edge membrane antigen to regulate neurite outgrowth in the cerebellum, cortex, and hippocampus neurons43,44. Post-translational modification with phosphorylation of tyrosine 251 at the C-terminus of M6a is essential for neuritogenesis in hippocampal neurons45. M6a colonizes at the glutamatergic excitatory presynaptic buttons and with vesicular glutamate transporter in the mossy fiber axon terminals46. M6a is localized in the myelin sheath, interacting with > 20 myelin proteins, and is essential for regulating post-synaptic activities (e.g.,47). The inefficient regulation of M6a might contribute to glutamate-related neural excitotoxicity, which is associated with tinnitus perception (e.g.,48).

Non-synonymous SNPs in GPM6A are associated with protein instability, making M6a non-functional in neurons45,49. M6a expression positively correlates with synaptic counts in hippocampal neurons49. M6a is also important for neural spine formation49. The dendritic spine formation is required for normal synaptic development and functioning. The abnormal synaptic functioning is implemented in psychiatric conditions (e.g.,50). GPM6A is associated with psychiatric traits, such as bipolar diseases, schizophrenia, depression, Alzheimer's disease, and claustrophobia (e.g.,51,52,53,54,55). M6a is associated with processing chronic stress in animal models, with chronic stress negatively correlated with gpm6a mRNA levels in the hippocampus56,57. These findings are consistent with a human study comparing GPM6A mRNA levels in the hippocampus in patients suffering from depression who committed suicide54. Together with the GWAS signals upregulated in the hippocampus, our results suggest that inefficient regulation of the genomic region associated with tinnitus involving GPM6A in the hippocampal neurons could influence tinnitus perception.

Another genomic region involving SHISA9 showed suggestive association with tinnitus. SNPs within the region are associated with neuroticism (rs275401, rs12926477), bipolar disorder (rs12935276), depression (rs7200826), and intelligence (rs62028752)56,57. SHISA9 is a protein-coding gene that encodes an auxiliary subunit of the AMPA-type glutamate receptors, which are highly expressed in the hippocampus dentate gyrus, cortex, and olfactory bulb58. SHISA9 can modulate the short-term plasticity of excitatory synapses59. SHISA9 is associated with schizophrenia, left ventricular hypertrophy, and tobacco use disorder60. Tinnitus is associated with reduced diastolic and systolic left ventricular mass and volume61. Tobacco smoking is consistently associated with tinnitus in large epidemiological studies (e.g.,1,2,3). In summary, the genomic region involving SHISA9 might influence synaptic plasticity contributing to tinnitus perception.

The genomic loci involving PSAP and TNRC6B showed suggestive association with tinnitus. The gene-based test identified associations between tinnitus and PSAP, and TNRC6B. PSAP encodes prosaposin, which is required for the catabolism of glycosphingolipids62. PSAP regulates the cochlear innervation patterns in the organ of the Corti63. Mutation in PSAP can cause prelingual profound sensorineural hearing loss64. TNRC6B is a protein-coding gene involved with the RNA interference machinery65. Mutations in TNRC6B are associated with childhood hearing loss, speech and language delay, fine-motor delay, autism traits, attention deficit, hyperactivity disorders, and musculoskeletal phenotypes66. TNRC6B can interact with Argonaute (AGO) family proteins to trigger mRNA decay in the cytoplasm67. We obtained SNPs in AGO2 and TNRC6B showing association with tinnitus. The interplay between AGO2 and TNRC6B might influence regulatory RNA mechanisms contributing to tinnitus. Further research is needed to evaluate these suggestive associations with tinnitus.

Tinnitus-related distress revealed suggestive associations with 15 SNPs (Table 4). A SNP close to ARAP2 achieved the lowest p-value. ARAP2 is essential for Akt signaling, glycolysis, and sphingolipid metabolisms68,69. ARAP2 is associated with impaired regulation of emotions, stress, depression, and bipolar disease70,71. The genomic region close to GPM6A associated with tinnitus revealed a suggestive association with tinnitus-related distress (Table 4). A SNP in TENM3, a gene involved with synaptic architecture development72,73, achieved suggestive significance. TENM3 is associated with schizophrenia and autoimmune disorders74,75. Our findings highlighted the polygenic architecture underlying tinnitus-related distress.

Enrichment analysis for the GWAS catalog reported genes

Genes associated with tinnitus were enriched in the gene sets for sensation seeking, psychiatric conditions, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic conditions, and response to pharmacological agents (Supplementary File S1). Sensation seekers might engage in risky auditory behaviors putting them at higher risk for acquiring tinnitus by exposure to intense sound levels and toxic chemicals in recreational and occupational settings (e.g.,76). Psychiatric conditions are common comorbidities associated with tinnitus. About 50% of clinical patients suffering from tinnitus report psychiatric comorbidities, such as depression, somatization, anxiety, and bipolar disorder77. Fast beta activity in electroencephalogram is associated with psychiatric traits, mental subnormality, major depression, and alcohol use disorder78. The fast beta activity in electroencephalogram is used as an endophenotype of mental subnormality to identify genetic variants associated with disinhibitory traits79,80,81. Tinnitus is associated with increased beta activity in the thalamic region82. The common genes between tinnitus, psychiatric conditions, and fast beta activity in electroencephalogram might present a comorbid genetic underpinning among these traits.

Cardiovascular diseases are known risk factors for tinnitus (e.g.,1,2,3). Hypertension, stroke, mean arterial pressure, and diastolic and systolic blood pressure gene sets revealed significant enrichment with tinnitus. The gene sets associated with the interaction between diastolic blood pressure and smoking, and interaction between diastolic and systolic blood pressure and alcohol consumption were significantly enriched in tinnitus. Smoking has consistently been associated with tinnitus, while the relationship between alcohol consumption and tinnitus remains elusive83. The gene sets related to body mass index revealed an association with tinnitus. Obesity is associated with a higher risk for tinnitus84. Besides, a wide range of ototoxic drugs could trigger tinnitus (e.g.,85). A recent GWAS obtained a suggestive association between Cisplatin-induced tinnitus and OTOS (rs7606353) highlighting a pharmacogenetic component to tinnitus86. In the present study, the gene sets associated with diuretics, fenofibrate, tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor, and metformin showed significant enrichment with tinnitus. Exposure to diuretics could disrupt the blood supply to stria vascularis and could induce transient ischemia allowing the toxic chemicals to pass through the cochlear barrier and inflicting irreversible damage to the organ of Corti, which could trigger tinnitus87. Fenofibrate is a pharmacological agent used for treating hypertriglyceridemia88, which is associated with tinnitus15. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha signaling is implemented in noise-induced tinnitus and hearing loss, and its inhibition might have therapeutic value for tinnitus89. Metformin is a therapeutic agent for treating type 2 diabetes90. The effect of metformin on tinnitus remains elusive. Metformin users might exhibit reduced vestibular schwannoma growth91, while some studies reported tinnitus and auditory symptoms as potential side effects of metformin92,93. In summary, our results suggest the pharmacogenetic component underlying tinnitus. Further research is required to identify the genetic variants underlying the interaction between tinnitus and pharmaceutical agents.

Gene sets associated with anxiety and stress-related disorders, cutaneous systematic scleroderma, heel bone mineral density, molar-incisor hypomineralization, and lumbar disc degeneration revealed significant enrichment with tinnitus-related distress. The association between tinnitus-related distress and anxiety and stress-related disorders highlighted common genetic underpinning between these comorbid conditions. Scleroderma is associated with a higher risk of tinnitus, hyperacusis, hearing loss, and abnormal speech perception94,95. The relationship between bone mineral density and tinnitus remains elusive. Reduced bone mineral density is associated with a higher risk for hearing loss among postmenopausal women96, and tinnitus is higher in patients with osteoporosis97. The relationships between tinnitus-related distress and molar-incisor hypomineralization and lumbar disc degeneration remain elusive. Further research is needed to identify the epidemiological risk factors underlying tinnitus-related distress.

Experimental caveats

The present study lacks an independent sample for the replication analysis. We utilized environmental covariates for conducting the GWAS analysis which resulted in losing some sample size and statistical power (Supplement File S1—Fig. 13). Besides, the present study used single questions to define tinnitus phenotypes, which could not efficiently quantify the biological processes underlying tinnitus and tinnitus-related distress. Tinnitus subphenotypes (e.g., noise-induced tinnitus, drug-induced tinnitus, psychometric features of tinnitus) remained unassessed in the present study. Deep phenotyping is required to quantify the multidimensional phenomenological reality of tinnitus and tinnitus-related distress. Environmental covariates used in the GWAS (such as noise and music exposures) were quantified with single questions. A comprehensive assessment of the environmental factors might yield greater precision.

Summary

We conducted a GWAS on the UK Biobank database (N = 132,438) to obtain SNPs associated with tinnitus and tinnitus-related distress. A genomic region containing SNP (rs71595470) near GPM6A revealed a significant association with tinnitus, and 19 SNPs showed suggestive associations with tinnitus. We obtained fifteen SNPs associated with tinnitus-related distress. The enrichment analysis with FUMA identified 23 gene sets associated with tinnitus. These gene sets included psychiatric conditions, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic conditions, and response to pharmaceutical agents. The enrichment analysis revealed association between tinnitus-related distress and anxiety and stress-related disorders, systemic scleroderma, and other conditions. The GWAS signals collectively enriched in hippocampus and cortex for tinnitus, and were enriched in brain, spinal cord, and cervical C-1 for tinnitus-related distress. In summary, our study highlighted a polygenic architecture underlying tinnitus and tinnitus-related distress.

Data availability

The study used the UK Biobank database. The database is publicly available through the UK Biobank website: https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/.

Abbreviations

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association study

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

References

Bhatt, J. M., Lin, H. W. & Bhattacharyya, N. Tinnitus epidemiology: Prevalence, severity, exposures and treatment patterns in The United States. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 142(10), 959 (2016).

Masterson, E. A., Themann, C. L., Luckhaupt, S. E., Li, J. & Calvert, G. M. Hearing difficulty and tinnitus among US workers and non-workers in 2007. Am. J. Ind. Med. 59(4), 290–300 (2016).

American Tinnitus Association. Impact of Tinnitus. (2019). https://www.ata.org/understanding-facts/impact-tinnitus. Accessed 14 May 2019.

Shargorodsky, J., Curhan, G. C. & Farwell, W. R. Prevalence and characteristics of tinnitus among US adults. Am. J. Med. 123(8), 711–718 (2010).

Chen, K. H., Su, S. B. & Chen, K. T. An overview of occupational noise-induced hearing loss among workers: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and preventive measures. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 25(1), 1–10 (2020).

Savastano, M. Tinnitus with or without hearing loss: Are its characteristics different?. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 265(11), 1295–1300 (2008).

Shore, S. E. & Wu, C. Mechanisms of noise-induced tinnitus: Insights from cellular studies. Neuron 103(1), 8–20 (2019).

Henry, J. A., Roberts, L. E., Caspary, D. M., Theodoroff, S. M. & Salvi, R. J. Underlying mechanisms of tinnitus: Review and clinical implications. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 25(01), 005–022 (2014).

Elgoyhen, A. B., Langguth, B., De Ridder, D. & Vanneste, S. Tinnitus: Perspectives from human neuroimaging. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16(10), 632–642 (2015).

Lee, H. M. et al. Epidemiology of clinically significant tinnitus: A 10-year trend from nationwide health claims data in South Korea. Otol. Neurotol. 39(6), 680–687 (2018).

Basso, L. et al. Subjective hearing ability, physical and mental comorbidities in individuals with bothersome tinnitus in a Swedish population sample. Prog. Brain Res. 260, 51–78 (2021).

Bhatt, I. S. Prevalence of and risk factors for tinnitus and tinnitus-related handicap in a college-aged population. Ear Hear. 39(3), 517–526 (2018).

Kirk, K. M. et al. Self-reported tinnitus and ototoxic exposures among deployed Australian defence force personnel. Mil. Med. 176(4), 461–467 (2011).

Nondahl, D. M. et al. Tinnitus and its risk factors in the Beaver Dam offspring study. Int. J. Audiol. 50(5), 313–320 (2011).

Cianfrone, G. et al. Pharmacological drugs inducing ototoxicity, vestibular symptoms and tinnitus: A reasoned and updated guide. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 15(6), 601–636 (2011).

Bhatt, J. M., Bhattacharyya, N. & Lin, H. W. Relationships between tinnitus and the prevalence of anxiety and depression. Laryngoscope 127(2), 466–469 (2017).

Cresswell, M. et al. Understanding factors that cause tinnitus: A mendelian randomization study in the UK Biobank. Ear Hear. 43(1), 70–80 (2022).

Lopez-Escamez, J. A. & Amanat, S. Heritability and genetics contribution to tinnitus. Otolaryngol. Clin. North Am. 53(4), 501–513 (2020).

Cederroth, C. R. et al. Association of genetic vs environmental factors in Swedish adoptees with clinically significant tinnitus. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 145(3), 222–229 (2019).

Bogo, R. et al. Prevalence, incidence proportion, and heritability for tinnitus: A longitudinal twin study. Ear Hear. 38(3), 292–300 (2017).

Maas, I. L. et al. Genetic susceptibility to bilateral tinnitus in a Swedish twin cohort. Genet. Med. 19(9), 1007–1012 (2017).

Vona, B., Nanda, I., Shehata-Dieler, W. & Haaf, T. Genetics of tinnitus: Still in its infancy. Front. Neurosci. 11, 236 (2017).

Clifford, R. E., Maihofer, A. X., Stein, M. B., Ryan, A. F. & Nievergelt, C. M. Novel risk loci in tinnitus and causal inference with neuropsychiatric disorders among adults of European ancestry. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 146(11), 1015–1025 (2020).

Wells, H. R., Abidin, F. N. Z., Freidin, M. B., Williams, F. M. & Dawson, S. J. Genome-wide association study suggests that variation at the RCOR1 locus is associated with tinnitus in UK Biobank. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 1–10 (2021).

Urbanek, M. E. & Zuo, J. Genetic predisposition to tinnitus in the UK Biobank population. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 1–11 (2021).

Gilles, A., Van Camp, G., Van de Heyning, P. & Fransen, E. A pilot genome-wide association study identifies potential metabolic pathways involved in tinnitus. Front. Neurosci. 11, 71 (2017).

Amanat, S. et al. Burden of rare variants in synaptic genes in patients with severe tinnitus: An exome based extreme phenotype study. EBioMedicine 66, 103309 (2021).

Welsh, S., Peakman, T., Sheard, S. & Almond, R. Comparison of DNA quantification methodology used in the DNA extraction protocol for the UK Biobank cohort. BMC Genomics 18(1), 1–7 (2017).

Bycroft, C. et al. Genome-wide genetic data on~ 500,000 UK Biobank participants. BioRxiv 1, 166298 (2017).

Mbatchou, J. et al. Computationally efficient whole-genome regression for quantitative and binary traits. Nat. Genet. 53(7), 1097–1103 (2021).

Watanabe, K., Taskesen, E., Van Bochoven, A. & Posthuma, D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat. Commun. 8(1), 1–11 (2017).

Kapolowicz, M. R. & Thompson, L. T. Plasticity in limbic regions at early time points in experimental models of tinnitus. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 13, 88 (2020).

Jastreboff, P. J. & Jastreboff, M. M. Tinnitus retraining therapy (TRT) as a method for treatment of tinnitus and hyperacusis patients. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 11(03), 162–177 (2000).

Besteher, B. et al. Chronic tinnitus and the limbic system: Reappraising brain structural effects of distress and affective symptoms. NeuroImage Clin. 24, 101976 (2019).

Chen, G. D., Manohar, S. & Salvi, R. Amygdala hyperactivity and tonotopic shift after salicylate exposure. Brain Res. 1485, 63–76 (2012).

Rauschecker, J. P., Leaver, A. M. & Mühlau, M. Tuning out the noise: Limbic-auditory interactions in tinnitus. Neuron 66(6), 819–826 (2010).

Profant, O. et al. The influence of aging, hearing, and tinnitus on the morphology of cortical gray matter, amygdala, and hippocampus. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12, 553461 (2020).

Li, Q. S., Parrado, A. R., Samtani, M. N., Narayan, V. A., Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Variations in the FRA10AC1 fragile site and 15q21 are associated with cerebrospinal fluid Aβ1-42 level. PLoS ONE 10(8), e0134000 (2015).

Lam, M. et al. Pleiotropic meta-analysis of cognition, education, and schizophrenia differentiates roles of early neurodevelopmental and adult synaptic pathways. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 105(2), 334–350 (2019).

Lee, J. J. et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nat. Genet. 50(8), 1112–1121 (2018).

Lugo, A. et al. Sex-specific association of tinnitus with suicide attempts. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 145(7), 685–687 (2019).

Tegg-Quinn, S., Bennett, R. J., Eikelboom, R. H. & Baguley, D. M. The impact of tinnitus upon cognition in adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Audiol. 55(10), 533–540 (2016).

Baumrind, N. L., Parkinson, D., Wayne, D. B., Heuser, J. E. & Pearlman, A. L. EMA: A developmentally regulated cell-surface glycoprotein of CNS neurons that is concentrated at the leading edge of growth cones. Dev. Dyn. 194(4), 311–325 (1992).

Lagenaur, C., Kunemund, V., Fischer, G., Fushiki, S. & Schachner, M. Monoclonal M6 antibody interferes with neurite extension of cultured neurons. J. Neurobiol. 23(1), 71–88 (1992).

Formoso, K., Billi, S. C., Frasch, A. C. & Scorticati, C. Tyrosine 251 at the C-terminus of neuronal glycoprotein M6a is critical for neurite outgrowth. J. Neurosci. Res. 93(2), 215–229 (2015).

Taoufiq, Z. et al. Hidden proteome of synaptic vesicles in the mammalian brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117(52), 33586–33596 (2020).

Pourhaghighi, R. et al. BraInMap elucidates the macromolecular connectivity landscape of mammalian brain. Cell Syst. 10(4), 333–350 (2020).

Sahley, T. L. & Nodar, R. H. A biochemical model of peripheral tinnitus. Hear. Res. 152(1–2), 43–54 (2001).

Formoso, K., Garcia, M. D., Frasch, A. C. & Scorticati, C. Evidence for a role of glycoprotein M6a in dendritic spine formation and synaptogenesis. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 77, 95–104 (2016).

Obi-Nagata, K., Temma, Y. & Hayashi-Takagi, A. Synaptic functions and their disruption in schizophrenia: From clinical evidence to synaptic optogenetics in an animal model. Proc. Jpn. Acad. B 95(5), 179–197 (2019).

Greenwood, T. A., Akiskal, H. S., Akiskal, K. K., Study, B. G. & Kelsoe, J. R. Genome-wide association study of temperament in bipolar disorder reveals significant associations with three novel Loci. Biol. Psychiatry 72(4), 303–310 (2012).

Pantelis, C. et al. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 511(7510), 421–427 (2014).

Muraoka, S. et al. Proteomic and biological profiling of extracellular vesicles from Alzheimer’s disease human brain tissues. Alzheimers Dement. 16(6), 896–907 (2020).

Fuchsova, B., Juliá, A. A., Rizavi, H. S., Frasch, A. C. & Pandey, G. N. Altered expression of neuroplasticity-related genes in the brain of depressed suicides. Neuroscience 299, 1–17 (2015).

Nagel, M. et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for neuroticism in 449,484 individuals identifies novel genetic loci and pathways. Nat. Genet. 50(7), 920–927 (2018).

Alfonso, J. et al. Regulation of hippocampal gene expression is conserved in two species subjected to different stressors and antidepressant treatments. Biol. Psychiat. 59(3), 244–251 (2006).

Savage, J. E. et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis in 269,867 individuals identifies new genetic and functional links to intelligence. Nat. Genet. 50(7), 912–919 (2018).

von Engelhardt, J. AMPA receptor auxiliary proteins of the CKAMP family. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20(6), 1460 (2019).

Von Engelhardt, J. et al. CKAMP44: A brain-specific protein attenuating short-term synaptic plasticity in the dentate gyrus. Science 327(5972), 1518–1522 (2010).

Rouillard, A. D. et al. The harmonizome: A collection of processed datasets gathered to serve and mine knowledge about genes and proteins. Database 2016, 100 (2016).

Esposti, D. D. et al. Haemodynamic profile of young subjects with transient tinnitus. Audiol. Med. 7(4), 200–204 (2009).

Xu, Y. H., Barnes, S., Sun, Y. & Grabowski, G. A. Multi-system disorders of glycosphingolipid and ganglioside metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 51(7), 1643–1675 (2010).

Akil, O. et al. Progressive deafness and altered cochlear innervation in knock-out mice lacking prosaposin. J. Neurosci. 26(50), 13076–13088 (2006).

Liaqat, K. et al. Phenotype expansion for atypical Gaucher disease due to homozygous missense PSAP variant in a large consanguineous Pakistani family. Genes 13(4), 662 (2022).

Baillat, D. & Shiekhattar, R. Functional dissection of the human TNRC6 (GW182-related) family of proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29(15), 4144–4155 (2009).

Granadillo, J. L. et al. Pathogenic variants in TNRC6B cause a genetic disorder characterised by developmental delay/intellectual disability and a spectrum of neurobehavioural phenotypes including autism and ADHD. J. Med. Genet. 57(10), 717–724 (2020).

Chen, C. Y. A., Zheng, D., Xia, Z. & Shyu, A. B. Ago-TNRC6 triggers microRNA-mediated decay by promoting two deadenylation steps. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16(11), 1160–1166 (2009).

Luo, R. et al. ARAP2 inhibits Akt independently of its effects on focal adhesions. Biol. Cell 110(12), 257–270 (2018).

Chaudhari, A., Håversen, L., Mobini, R., Andersson, L., Ståhlman, M., Lu, E., Borén, J. (2016). ARAP2 promotes GLUT1-mediated basal glucose uptake through regulation of sphingolipid metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids, 161(11), 1643–1651.

Caradonna, S. G. et al. Genomic modules and intramodular network concordance in susceptible and resilient male mice across models of stress. Neuropsychopharmacology 47(5), 987–999 (2022).

Pandey, A. et al. Epistasis network centrality analysis yields pathway replication across two GWAS cohorts for bipolar disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2(8), e154–e154 (2012).

Antinucci, P., Nikolaou, N., Meyer, M. P. & Hindges, R. Teneurin-3 specifies morphological and functional connectivity of retinal ganglion cells in the vertebrate visual system. Cell Rep. 5(3), 582–592 (2013).

Young, T. R. & Leamey, C. A. Teneurins: Important regulators of neural circuitry. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 41(5), 990–993 (2009).

Li, S., DeLisi, L. E. & McDonough, S. I. Rare germline variants in individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia within multiplex families. Psychiatry Res. 303, 114038 (2021).

Li, Y. R. et al. Meta-analysis of shared genetic architecture across ten pediatric autoimmune diseases. Nat. Med. 21(9), 1018–1027 (2015).

Welch, D. & Fremaux, G. Understanding why people enjoy loud sound. Semin. Hear. 38(04), 348–358 (2017).

Salviati, M. et al. A brain centred view of psychiatric comorbidity in tinnitus: from otology to hodology. Neural Plast. 2014, 1–15 (2014).

Drake, M. E. Jr. Clinical correlates of very fast beta activity in the EEG. Clin. Electroencephalogr. 15(4), 237–241 (1984).

Gottesman, I. I. & Gould, T. D. The endophenotype concept in psychiatry: Etymology and strategic intentions. Am. J. Psychiatry 160(4), 636–645 (2003).

Porjesz, B. et al. The utility of neurophysiological markers in the study of alcoholism. Clin. Neurophysiol. 116(5), 993–1018 (2005).

Meyers, J. L. et al. An endophenotype approach to the genetics of alcohol dependence: A genome wide association study of fast beta EEG in families of African ancestry. Mol. Psychiatry 22(12), 1767–1775 (2017).

Vanneste, S. et al. The neural correlates of tinnitus-related distress. Neuroimage 52(2), 470–480 (2010).

Biswas, R. et al. Modifiable lifestyle-related risk factors for tinnitus in the general population: An overview of smoking, alcohol, body mass index and caffeine intake. Prog. Brain Res. 263, 1–24 (2021).

Gallus, S. et al. Prevalence and determinants of tinnitus in the Italian adult population. Neuroepidemiology 45(1), 12–19 (2015).

Altissimi, G. et al. Drugs inducing hearing loss, tinnitus, dizziness and vertigo: an updated guide. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 24(15), 7946–7952 (2020).

El Charif, O. et al. Clinical and genome-wide analysis of cisplatin-induced tinnitus implicates novel ototoxic mechanismsgenetics of cisplatin-induced ototoxicity. Clin. Cancer Res. 25(13), 4104–4116 (2019).

Kim, S. H. et al. Review of pharmacotherapy for tinnitus. Healthcare 9(6), 779 (2021).

McKeage, K. & Keating, G. M. Fenofibrate. Drugs 71(14), 1917–1946 (2011).

Shulman, A. et al. Neuroinflammation and tinnitus. Behav.Neurosci. Tinnitus 1, 161–174 (2021).

Tulipano, G. Integrated or independent actions of metformin in target tissues underlying its current use and new possible applications in the endocrine and metabolic disorder area. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(23), 13068 (2021).

Feng, A. Y., Enriquez-Marulanda, A., Kouhi, A., Moore, J. M. & Vaisbuch, Y. Metformin potential impact on the growth of vestibular schwannomas. Otol. Neurotol. 41(3), 403–410 (2020).

Tsakiridis, T. et al. Metformin in combination with chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer: the OCOG-ALMERA randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 7(9), 1333–1341 (2021).

Maarup, N., Palaian, S., Ibrahim, M. I. M., Khanal, S. & Alshakka, M. Possible metformin-induced otorrhoea: A rare case. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 41, 1 (2011).

Shenavandeh, S., Hashemi, S. B., Masoudi, M., Nazarinia, M. A. & Zare, A. Hearing loss in patients with scleroderma: Associations with clinical manifestations and capillaroscopy. Clin. Rheumatol. 37(9), 2439–2446 (2018).

Maciaszczyk, K., Waszczykowska, E., Pajor, A., Bartkowiak-Dziankowska, B. & Durko, T. Hearing organ disorders in patients with systemic sclerosis. Rheumatol. Int. 31(11), 1423–1428 (2011).

Lee, S. S. & Joo, Y. H. Association between low bone mineral density and hearing impairment in postmenopausal women: The Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. BMJ Open 8(1), e018763 (2018).

Kahveci, O. K., Demirdal, U. S., Yücedag, F. & Cerci, U. Patients with osteoporosis have higher incidence of sensorineural hearing loss. Clin. Otolaryngol. 39(3), 145–149 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant R21DC016704-01A1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.B. and A.T. prepared the main manuscript text, and N.W. and R.D. conducted the statistical analyses.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bhatt, I.S., Wilson, N., Dias, R. et al. A genome-wide association study of tinnitus reveals shared genetic links to neuropsychiatric disorders. Sci Rep 12, 22511 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-26413-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-26413-6

This article is cited by

-

Genetic architecture distinguishes tinnitus from hearing loss

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Repurposing metformin to manage idiopathic or long COVID Tinnitus: self-report adopting a pathophysiological and pharmacological approach

Inflammopharmacology (2024)

-

A Systematic Review on the Genetic Contribution to Tinnitus

Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.