Abstract

Timothy syndrome (TS) is a rare pleiotropic disorder associated with long QT syndrome, syndactyly, dysmorphic features, and neurological symptoms. Several variants in exon 8 or 8a of CACNA1C, a gene encoding the α-subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Cav1.2), are known to cause classical TS. We identified a p.R412M (exon 9) variant in an atypical TS case. The aim of this study was to examine the functional effects of CACNA1C p.R412M on CaV1.2 in comparison with those of p.G406R. The index patient was a 2-month-old female infant who suffered from a cardio-pulmonary arrest in association with prolonged QT intervals. She showed dysmorphic facial features and developmental delay, but not syndactyly. Interestingly, she also presented recurrent seizures from 4 months. Genetic tests identified a novel heterozygous CACNA1C variant, p.R412M. Using heterologous expression system with HEK-293 cells, analyses with whole-cell patch-clamp technique revealed that p.R412M caused late Ca2+ currents by significantly delaying CaV1.2 channel inactivation, consistent with the underlying mechanisms of classical TS. A novel CACNA1C variant, p.R412M, was found to be associated with atypical TS through the same mechanism as p.G406R, the variant responsible for classical TS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Timothy syndrome (TS) is a rare pleiotropic disorder associated with long QT syndrome (LQTS, type 8), congenital heart disease, syndactyly, dysmorphic features, immunodeficiency, intermittent hypoglycemia, and neurologic symptoms including autism, seizures, and intellectual disability1,2. TS is caused by missense variants in CACNA1C, the gene encoding the α-subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (CaV1.2)2,3. A functional study showed that p.G406R in exon 8a, which is responsible for TS1, significantly slowed the voltage-dependent inactivation (VDI) kinetics, resulting in sustained late Ca2+ currents1. Although syndactyly is a common feature of the classical form of TS1, two atypical patients who showed severe cardiac deficits did not have syndactyly; furthermore they differed genetically, and thus were later categorized as TS24. TS2 patients were found to carry heterozygous missense variants, p.G406R and p.G402S, in a mutually exclusive exon 8. Exon 8 is more predominantly expressed in the heart compared to exon 8a. It is thought that the different expression levels of two transcripts containing either exon 8a or 8 account for those different phenotypes; TS1 patients exhibit a more severe form of extra-cardiac features than TS21,4.

We experienced a female infant who suffered from cardiac arrest due to Torsade de Pointes (TdP) in association with Timothy syndrome without syndactyly, which mimics TS2. The patient also presented developmental delay and was complicated with recurring seizure attacks. We identified a heterozygous de novo CACNA1C variant p.R412M that was located six amino acids downstream to G406R and between domain I-S6 (IS6) and α1 interacting domain (AID). The AID is known as the binding site for ancillary β-subunit, a potent modulator of voltage-dependent calcium channels. In the present study, we described the clinical phenotypes of the patient and analyzed the functional effects of p.R412M variant on CaV1.2. We also conducted the functional assay of the p.G406R, a variant found in TS1.

Results

Clinical features of index patient

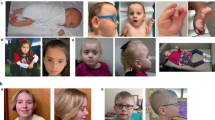

The patient was a 2-month-old female infant born after 37 weeks of gestation with a birth weight of 2730 g. Fetal bradycardia had been identified at gestational age of 33 weeks, but no cardiac rhythm disorder was noted at birth. Her face was characterized by dysmorphic features such as high arched palate, full cheeks, and congenital clasped thumb, but no syndactyly. At 2 months, she experienced her first episode of syncope due to repetitive TdPs that degenerated into VF.

Her ECG revealed typical T wave alternans, markedly prolonged QT-intervals (RR = 570 ms, QT = 501 ms, QTc = 664 ms, Fig. 1A), 2:1 atrio-ventricular (AV) block, and recurrence of TdP (Fig. 1B). The echocardiography showed no congenital heart defects nor hypertrophy. We suspected LQTS type 3 (LQT3) from the T-wave morphology, depicting a late-onset peaked T-wave. Therefore, mexiletine was administered as an initial therapy. An intravenous injection of mexiletine (1.5 mg/kg) followed by the maintenance dose of oral mexiletine (30 mg/kg/day) resolved the 2:1 AV block to a 1:1 conduction (Fig. 1C). In addition, we started propranolol (2 mg/kg/day), which suppressed recurrence of TdP.

Electrocardiograms (ECG) of a 2-month-old female infant with Timothy syndrome, showing (A) T-wave alternans, (B) 2:1 atrio-ventricular block and torsades de pointes, (C) before and after the intravenous mexiletine, and (D) after oral administration of mexiletine and propranolol. Red arrows in (B) and (C) indicate P waves.

The patient also suffered from recurrent seizures unrelated to TdPs from 4 months after birth. An electroencephalogram at the age of 7 months displayed hypsarrhythmia. She showed severe developmental disability and hypotonia, and thus she was barely able to roll over at the age of 3. The patient was also diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder at the age of 2. There were no findings that indicated hypoglycemia or immunodeficiency related to TS.

With the medications, the patient’s ECG at the age of 5 showed slightly prolonged QTc (RR = 559 ms, QT = 346 ms, QTc = 462 ms; Fig. 1D). Since the pharmacotherapy successfully suppressed her TdP, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) was not implanted. Unfortunately, the patient suddenly passed away at 5 years old during a nap. Her family history was negative for SCD, LQTS, arrhythmia, or neurological abnormalities.

Genetic analysis

Genetic tests using a gene panel as described in the “Methods” section identified a novel heterozygous missense variant p.R412M in CACNA1C. This variant was confirmed by the Sanger method (Fig. 2A). The arginine at position 412 is highly conserved among different species (Fig. 2B). The patient's parents were both negative for this variant, indicating a de novo mutation within this family. Their paternity and maternity were confirmed by screening 12 rare single nucleotide polymorphisms (data not shown).

(A) Electropherograms of WT and p.R412M. (B) Alignment of p.R412M. (C) Topology of CaV1.2 α-subunit (S, segment; D, domain) with classical TS (TS1, pink circles), TS2 (orange triangles), or atypical TS (yellow diamond) -related mutations. TS1. Timothy syndrome type 1; TS2, Timothy syndrome type 2; Atypical TS, Atypical Timothy syndrome; AID, α1 interacting domain.

Figure 2C illustrates a topology of CACNA1C in which known TS-related mutations identified to date are highlighted. The variant identified in this study is indicated in red (with an arrow). Arginine 412 is located in the inner loop of the membrane, between IS6 and binding site for ancillary β-subunit (AID). The p.R412M variant has not been previously reported in at least two online databases: TOGOVAR (https://togovar.biosciencedbc.jp/) and gnomAD (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/). The variants with functional evidence were confirmed as pathogenic based on the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guideline for the interpretation of sequence variants5.

Functional analysis

Electrophysiological parameters

We examined the electrophysiological characteristics of WT, R412M, and G406R CaV1.2 channels. Figure 3A shows representative current traces recorded from HEK-293 cells transiently transfected with WT (left), R412M (right upper), or G406R (right lower) CACNA1C. Maximal peak current densities were not significantly different among the three types of cells (ICa,WT: − 12.3 ± 0.95 pA/pF at + 20 mV ICa,R412M: − 10.9 ± 0.75 pA/pF at + 10 mV, ICa,G406R: 11.0 ± 1.7 pA/pF at + 10 mV; p = 0.42). In contrast, the inactivation decay of reconstituted Ca2+ currents was significantly slower in R412M- and G406R-transfected cells compared to those with WT (ICa,WT). Table 1 summarizes the biophysical parameters measured from multiple cells.

(A) Three sets of representative current traces for WT, R412M, and G406R ICa elicited by the protocol shown in the inset. (B) peak current density–voltage relationships, (C) steady state activation curves and (D) inactivation time constants for three different ICa: WT (black circles, n = 18), R412M (red squares, n = 10) and G406R (blue diamonds, n = 5). *P < 0.05 R412M vs. WT. †P < 0.05 G406R vs. WT. ‡P < 0.05 R412M vs. G406R.

Figure 3B shows plots of current–voltage (IV) relationships of ICa,WT (black), ICa,R412M (red), and ICa,G406R (blue). The voltage at the peak inward currents was more leftward-shifted in ICa,R412M and ICa,G406R than in ICa,WT. Figure 3C shows the steady-state activation at various test potentials for ICa,WT, ICa,R412M, and ICa,G406R. Experimental data were fitted with the Boltzmann function described in the “Methods” section (Eq. (2)). The steady-state activation (SSA) curves for ICa,R412M and ICa,G406R were significantly shifted toward negative compared to ICa,WT (Table 1).

Ca2+ current inactivation decay was significantly delayed by the variants found in TS

The decay of ICa during depolarization represents fast and slow kinetics, which mainly correspond to Ca-calmodulin-dependent (CDI) and voltage-dependent inactivation (VDI), respectively. Therefore, the time course of Ca2+ current decay was fitted to a double exponential function to evaluate time constants for fast and slow components (τfast and τslow: Eq. (3)). In Fig. 3D, τfast and τslow are plotted against test potentials (from 0 to + 20 mV). The τfast values for ICa,R412M and ICa,G406R were significantly larger than those for ICa,WT, while the relative amplitude of the fast component (Afast) of ICa,R412M was comparable to that of ICa,WT (Table 1). As for the slow component that is largely attributable to VDI, the τslow values were significantly larger and the relative amplitudes were smaller than ICa,WT for both in ICa,R412M and ICa,G406R.

Figure 4A depicts three sets of current traces elicited by a double-pulse voltage protocol (inset panel). Both ICa,R412M and ICa,G406R showed the persistent late inward Ca2+ currents even at the end of 500-ms test pulse. In Fig. 4B, the peak inward current amplitudes measured at + 20 mV from various test potentials were normalized against their maximal values and are plotted as a function of test voltage. Experimental data were then fitted with the Boltzmann function (Eq. (2) in “Methods” section) to calculate the half-maximal voltage of inactivation (Table 1). While ICa,WT were completely inactivated at + 20 mV, ICa,R412M and ICa,G406R were not inactivated even at + 50 mV (maximal inactivation level of 78% and 54%, respectively). Compared to ICa,WT, the voltage-dependency of steady-state inactivation (SSI) was rightward-shifted to the positive by 7.7 mV in ICa,R412M and 1.8 mV in ICa, G406R (Table 1). Figure 4C depicts both activation and inactivation curves for ICa,WT, ICa,R412M, and ICa,G406R on the same scale. Due to the negative shift of the activation gate and drastic positive shift of the inactivation gate, the window current (Iw) markedly increased in both R412M (red) and G406R (blue) Cav1.2 channels. Referencing a previous report6, we then calculated the Iw by first multiplying SSA and SSI to give the open probability of L-type calcium channels (Po(V) (Fig. 4C, dotted curves), and then multiplied by Gmax and the driving force (V–Vrev) to estimate the amount of Iw in WT (black), R412M (red) and G406R (blue) Cav1.2 channels (Fig. 4D: Eq. (4) in “Methods” section). This kind of Iw quantification clearly represents that Iw of R412M and G406R Cav1.2 channels were larger than that of WT.

(A) Three sets of representative current traces for WT, R412M, and G406R ICa elicited recorded by a double step pulse protocol in the inset. (B) inactivation voltage-dependence curves for WT (black circles, n = 15) and R412M (red squares, n = 12) and G406R (blue diamonds, n = 6) ICa. (C) Both activation and inactivation curves are plotted on the same scale. The probability of channel opening Po(V) curves were obtained by multiplying G/Gmax by I/Imax (dotted curves). (D) The window currents (Iw) calculated by multiplying Po(V) by Gmax and the driving force (V–Vrev) and were normalized by the maximum Iw at 0 mV in G406R. Vrev means reversal potential.

p.R412M variant mainly affected voltage-dependent inactivation

TO further investigate whether p.R412M Cav1.2 channels are affected by alterations of VDI or CDI, we examined characteristics of Cav1.2 using barium (Ba2+) as a charge carrier, which allowed us to exclude CDI as previously described7. Fig. 5A presents typical current traces of ICa and IBa in two different HEK-293 cells expressing WT or R412M Cav1.2 after adjusting the peak inward current levels. We then compared the inactivation time course of ICa,WT vs. IBa,WT (left) as well as ICa,R412M vs. IBa,R412M (right). When Ca2+ ions were present as a charge carrier, the inactivation process was accelerated, indicating the presence of CDI. The degree of CDI was estimated by measuring the ratio of currents remaining at the end of 200-ms depolarization to peak inward currents (r200). The values of r200 thus calculated are plotted as a function of test potential in Fig. 5B. Then, as shown by Eq. (5), the extent of CDI was evaluated as f200, the fraction of current reduction from IBa to ICa (r200,Ba–r200/Ca)7,8. The values of f200 or the component of CDI are plotted against test potentials (Fig. 5C). These values were not significantly different between WT and R412M, indicating that the variant did not significantly affect the CDI but slowed the current decay through the VDI process as shown by time constants of inactivation (Fig. 3D).

(A) Four sets of representative current traces from two different cells expressing either WT (left) or R412M (right) CACNA1C as Ca2+ (black, ICa) or Ba2+ (red, IBa) as a charge carrier at 0 mV (upper panel) and + 20 mV (lower panel). (B) Voltage-dependences were evaluated as r200 (B) and f200 (C) at various depolarization for WT (n = 5) and R412M (n = 5) and are plotted as a function of test membrane potentials. (D) Using the double pulse protocol as shown in Fig. 4A, the voltage-dependency of IBa inactivation was examined for WT (filled black circles, n = 10) and R412M (filled red squares).

Finally, we examined the steady-state inactivation of IBa,R412M through a double voltage pulse method used in the experiment shown in Fig. 4. Figure 5D shows the voltage-dependency of steady-state inactivation for WT and R412M Cav1.2 currents with Ba2+ ion as a charge carrier. The VDI measured as IBa,R412M was also rightward shifted toward the positive direction by 9.6 mV compared to IBa,WT. Maximal inactivation of IBa,R412M still remained 66%, indicating that the failure of VDI is indeed the main cause for drastically slowed current decay as previously reported in G406R variant1,4.

Discussion

In the present study, we found a novel CACNA1C variant, p.R412M, in a female infant. The variant is located in an α-helical domain between IS6 and AID, close to two previously reported TS variants: p.G406R found in TS1 (exon 8a)1,2 or TS2 (exon 8)2,4 (Fig. 2C). Functional analyses using a heterologous expression system revealed that p.R412M caused a hyperpolarizing shift of SSA gate (Fig. 3C) and a drastic depolarizing shift of SSI gate (Fig. 4B), resulting in a greater window current (Fig. 4D) and persistent late Ca2+ currents at membrane potentials more positive than − 20 mV. Changes in SSA and SSI for ICa, G406R observed in our experimental condition were consistent with previous reports1,4,9. For the measurement of SSI, they used a 2-s pre-pulse duration, while we used a pre-pulse of 500 ms. However, Ferreira et al. indicated that inactivation of ICa required longer than 5 s to reach steady state10. Therefore, only the fast component of inactivation may have been studied in our study. In the study of heterozygous TS2-neo mice, the G406R variant shifted SSI leftward with a pre-pulse of 5 s6, which might be more precise for ICa, G406R.

It has been reported that two types of mechanisms, VDI and CDI, are involved in the inactivation of ICa. Experiments using IBa revealed that p.R412M mainly affected VDI. Therefore, its overall biophysical effects were similar to those of p.G406R, causing the very severe TS-related cardiac phenotypes in our patient.

The IS6-AID linker, where the arginine at position 412 is located in, provides physical interactions between the CaV1.2 β-subunit and the channel pore. This interaction between two domains is thought to be pivotal for the smooth VDI gating of the channel11. Previous studies showed that an increased rigidity of the IS6-AID linker decelerates the time course of Cav1.2 VDI11,12. This rigid stabilization was proposed to be the pathophysiological mechanism behind the G406R variant (both in TS1 and TS2), which critically slowed the inactivation kinetics12. As the topological location is close to these classical TS mutations, p.R412M may also increase the rigidity of the IS6-AID linker, thereby slowing the VDI process.

Our index patient presented a marked QT-prolongation that was longer than the QT-intervals in TS1 patients1, with a more severe cardiac phenotype than those observed in reported TS1 cases. Therefore, the clinical features of our patient resembled those of TS2 patients. The variant p.G406R in TS1 is translated from exon 8a, and the variant p.R412M found in our patient is translated from exon 9. It has been reported that expression levels of the CACNA1C transcript containing an alternatively spliced exon 8a represent approximately only 20% of the total cardiac CACNA1C transcript, while exon 9 is 100% translated since no alternative transcripts exist1,2,4,13. In contrast, the majority of cardiac CACNA1C transcripts contain the mutually spliced exon 8. Thus, TS2 patients bearing p.G406R in exon 8 might show severe cardiac phenotypes comparable to p.R412M2,4. These differences in genetic backgrounds may account for the various severity of clinical outcomes1,2,4.

Although we observed that the R412M mutation did not affect the CDI largely just as the p.G406R variant previously found in classical TS patients, Dick et al. demonstrated that the G406R mutation caused significant defects in CDI of the channel8. They co-expressed β2a auxiliary subunit which decreased VDI in Ca2+ channels in order to examine CDI precisely. However, we used β2b auxiliary subunit according to the previously reported “Methods” section7. Therefore, we could not deny the CDI impairment by R412M in in situ hearts.

TS is an extremely rare syndromic disease, and approximately 50 cases have been described to date2. Later on, variants located outside of exon 8/8a were identified: p.E407G, p.E407A, p.G419R, p.S643F, p.C1021R, p.E1115K, p.I1166T, p.A1473G, and p.G1911R in atypical TS patients (Fig. 2C)14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. More recently, a wide variety of phenotypes in CACNA1C variant carrier have been reported, including those expressing only cardiac features or even long QT syndrome (LQT8) alone17,23,24,25.

Considering that the heart is the most frequently affected organ in TS, ECG would be a useful tool to diagnose and determine the prognosis. As seen in our patient, key features are: extremely prolonged QT intervals (QTc > 600 ms); 2:1 atrio-ventricular block and recurrent TdP; and macroscopic T-wave alternans. These ECG changes in TS are more prominent compared to the other congenital LQTS’s. When encountering such cases, irrespective of presence or absence of extra-cardiac phenotypes, it would be of clinical importance to conduct genetic testing including that of CACNA1C.

Limitation

We could not completely exclude the possibility that other variants might contribute to extracardiac symptoms because a whole exome or genome sequencing was not done. We conducted an electrophysiological study using CACNA1C cDNA containing alternative exon 8a. We did not confirm whether a CACNA1C variant, p.R412M, caused the same electrophysiological effects on Cav1.2 when exon 8 expressed. In addition, for the measurement of SSI, we employed a short pre-pulse duration, which may have caused ‘quasi’-steady state inactivation and window current.

Conclusion

In a female infant with the atypical TS mimicking TS2 features and sudden cardiac death, we identified a novel heterozygous CACNA1C variant, p.R412M. Functional assay of p.R412M showed a significant VDI deceleration of CaV1.2 channel, consistent with the TS1 variant p.G406R. Our study indicates that patients with TS who carry pathogenic CACNA1C variants should be carefully observed to prevent unexpected sudden cardiac death.

Methods

Genetic screening

In accordance with study protocol that was approved by the review board at Shiga University of Medical Science and complied the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, genetic analysis was performed after written informed consent was obtained from the parent of the proband. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes. Coding and splice-site regions of 56 genes including LQTS-related genes (Supplementary Table 1) were all screened via targeted gene sequencing using a next generation sequencer (Miseq, Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA)26. For confirmation, direct DNA sequencing was conducted on an ABI PRISM-3130 Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The GenBank accession number of CACNA1C is NM_000719.6. We confirmed the pathogenicity of the variants according to Varsome (https://varsome.com/) and ACMG guideline for the interpretation of sequence variants5.

Mutagenesis and transient transfection

The human wild-type (WT) CACNA1C cDNA (NM_000719), which contains alternative exon 8a, in a pcDNA vector, and cDNAs of CACNB2b and CACNA2D1, both cloned into a pcDNA3.1 vector, were used. The vectors were kindly donated by Prof. Charles Antzelevitch (Lankenau Institute for Medical Research, USA). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using a QuickChange II XL kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). Mutated genes, CACNA1C R412M and G406R, were functionally expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells. HEK-293 cells were co-transfected with WT or mutant CACNA1C cDNAs (1 µg each) along with CACNB2b (1 µg), CACNA2D1 (1 µg), and Green Fluorescence Protein (GFP, 0.25 µg) using 6 µl of Fugene 6 (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Cells were employed for electrophysiological experiments 24–36 h after transfection.

Electrophysiology

A whole-cell mode patch-clamp technique was employed to measure WT and mutant Ca2+ currents at 25–26 °C using an Axopatch 200B patch-clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA). We used 1 µM of nisoldipine to dissect reconstituted L-type calcium currents (ICa) by digital subtraction. The extracellular (bath) solution contained (mmol/L): 130 NMDG-Cl, 5 KCl, 15 CaCl2 (or BaCl2), 1 MgCl2, and 10 HEPES. The pipette solution contained (mmol/L): 120 CsCl, 2 MgCl2, 2 MgATP, 10 HEPES, 5 CaCl2, and 10 EGTA (pH was adjusted to 7.25 with CsOH)7. Free Ca2+ concentration in the pipette solution was adjusted to be 100 nM by adding appropriate amounts of CaCl2 calculated by the Patcher’s Power Tools package (Igor ProTMTool software, version 1.0.6, 1997, © 1995–1997, Dr Francisco Mendez, Dept. of Membrane Biophysics, MPIbpc Gottingen, Germany). Patch pipettes were prepared using a P-97 puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA, USA) and were fire-polished to a final resistance of 2–3 MΩ.

To study the voltage dependence of channel activation, a single-step voltage protocol was used: depolarizing test pulses with 1-s durations were applied between − 50 and + 40 mV in 10 mV increments from a holding potential of − 70 mV. Data were analyzed using Clampfit (Axon Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and fitted with Igor Pro or Prism 7 (GraphPad Software Inc. ver.9). Peak current densities at each potential were obtained by dividing the cell capacitance.

Ca current–voltage (ICa–V) curves were fitted with the Boltzmann function of the following form:

where ICa(V) indicates ICa (pA/pF) at the membrane potential of V (mV), Gmax is maximum conductance density, Vrev is the reversal potential, Vh is the activation midpoint voltage, and k is the slope factor which determines the voltage dependence of channel activation.

The steady-state activation (SSA) and inactivation (SSI) curves were fitted with Boltzmann function of the following form:

where G/Gmax(V) indicates normalized ICa SSA, and I/Imax(V) SSI at the membrane potential V, respectively.

To obtain the inactivation time constant, the time course of inactivating currents for the first 300 ms at 0, + 10, and + 20 mV were fitted with a double exponential function:

where ICa(t) is the calcium current at time t (ms), A is the current amplitude, and τ (ms) is the inactivation decay time constant.

The probability of a channel opening at the membrane potential V (Po(V)) was obtained by multiplying G/Gmax(V) by I/Imax(V). The window currents (IW) were quantified by the equation.

To analyze the underlying mechanisms of the inactivation of Ca2+ currents, WT or R412M CaV1.2 currents were measured using extracellular (bath) CaCl2 or BaCl2 solutions in the same cells. Then, fractions of peak currents remaining after 200-ms depolarization were normalized to a peak current (r200) at various test potentials. The fractions of CDI were calculated as7,8:

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using the SPSS 22.0 statistical package (IBM, Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Differences between the two groups were evaluated using Mann–Whitney’s U test. Differences were accepted as statistically significant for p values < 0.05. For comparisons among the three groups, one-way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis tests were performed. Bonferroni correction was used for post hoc pairwise comparison. Continuous patch-clamp data are expressed as a mean (± SEM or 95% CI).

Data availability

The datasets of the novel variant p.R412M in CACNA1C are registered in the dbSNP repository (ss2137544377, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/snp_ss.cgi?ss=2137544377). Other datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Splawski, I. et al. Cav1.2 calcium channel dysfunction causes a multisystem disorder including arrhythmia and autism. Cell 119, 19–31 (2004).

Bauer, R., Timothy, K. W. & Golden, A. Update on the molecular genetics of Timothy syndrome. Front. Pediatr. 9, 668546 (2021).

Marcantoni, A., Calorio, C., Hidisoglu, E., Chiantia, G. & Carbone, E. CaV1.2 channelopathies causing autism: New hallmarks on Timothy syndrome. Pflug. Arch. 472, 775–789 (2020).

Splawski, I. et al. Severe arrhythmia disorder caused by cardiac L-type calcium channel mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 8089–8096 (2005).

Richards, S. et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 17, 405–424 (2017).

Calorio, C. et al. Impaired chromaffin cell excitability and exocytosis in austic Tmothy syndrome TS2-neo mouse rescued by L-type calcium channel blockers. J. Physiol. 597, 1705–1733 (2019).

Boczek, N. J. et al. Novel Timothy syndrome mutation leading to increase in CACNA1C window current. Heart Rhythm 12, 211–219 (2015).

Dick, I. E., Joshi-Mukherjee, R., Yang, W. & Yue, D. T. Arrhythmogenesis in Timothy syndrome is associated with defects in Ca2+-dependent inactivation. Nat. Commun. 7, 10370 (2016).

Yazawa, M. et al. Using induced pluripotent stem cells to investigate cardiac phenotypes in Timothy syndrome. Nature 471, 230–234 (2011).

Ferreira, G., Rios, E. & Reyes, N. Two components of voltage-dependent inactivation in CaV1.2 channels revealed by its gating currents. Biophys. J. 84, 3662–3678 (2003).

Opatowsky, Y., Chen, C. C., Campbell, K. P. & Hirsch, J. A. Structural analysis of the voltage-dependent calcium channel β subunit functional core and its complex with the α1 interaction domain. Neuron 42, 387–399 (2004).

Almagor, L. et al. The role of a voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel intracellular linker: A structure-function analysis. J. Neurosci. 32, 7602–7613 (2012).

Liao, P., Yong, T. F., Liang, M. C., Yue, D. T. & Soong, T. W. Splicing for alternative structures of CaV1.2 Ca2+ channels in cardiac and smooth muscles. Cardiovasc. Res. 68, 197–203 (2005).

Po’, C. et al. Photosensitive epilepsy and long QT: Expanding Timothy syndrome phenotype. Clin. Neurophysiol. 130, 2134–2136 (2019).

Bisabu, K. K. et al. Novel gain-of-function variant in CACNA1C associated with Timothy syndrome, multiple accesory pathways, and noncompacted cardiomyopathy. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 13, e003123 (2020).

Dufendach, K. A. et al. Clinical outcomes and modes of death in Timothy syndrome a multicenter international study of a rare disorder. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 4, 459–466 (2018).

Wemhoner, K. et al. Gain-of-function mutations in the calcium channel CACNA1C (Cav1.2) cause non-syndromic long-QT but not Timothy syndrome. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 80, 186–195 (2015).

Gillis, J. et al. Long QT, syndactyly, joint contractures, stroke and novel CACNA1C mutation: Expanding the spectrum of Timothy syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 158A(1), 182–187 (2012).

Colson, C. et al. Unusual clinical description of adult with Timothy syndrome, carrier of a new heterozygote mutation of CACNA1C. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 62, 103648 (2019).

Ozawa, J. et al. A novel CACNA1C mutation identified in a patient with Timothy syndrome without syndactyly exerts both marked loss- and gain-of-function effects. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 4, 273–277 (2018).

Ye, D., Tester, D. J., Zhou, W., Papagiannis, J. & Ackerman, M. J. A pore-localizing CACNA1C-E1115K missense mutation, identified in a patient with idiopathic QT prolongation, bradycardia, and autism spectrum disorder, converts the L-type calcium channel into a hybrid nonselective monovalent cation channel. Heart Rhythm 16, 270–278 (2019).

Hennessey, J. A. et al. A CACNA1C variant associated with reduced voltage-dependent inactivation, increased Cav1.2 channel window current, and arrhythmogenesis. PLoS ONE 9, e106982 (2014).

Fukuyama, M. et al. Long QT syndrome type 8: Novel CACNA1C mutations causing QT prolongation and variant phenotypes. Europace 16, 1828–1837 (2014).

Boczek, N. J. et al. Exome sequencing and systems biology converge to identify novel mutations in the L-type calcium channel, CACNA1C, linked to autosomal dominant long QT syndrome. Circ. Cadiovasc. Genet. 6, 279–289 (2013).

Boczek, N. J. et al. Identification and functional characterization of a novel CACNA1C-mediated cardiac disorder characterized by prolonged QT intervals with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, congenital heart defects, and sudden cardiac death. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 8, 1122–1132 (2015).

Ozawa, J. et al. Differential diagnosis between catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and long QT syndrome type 1-modified Schwartz score. Circ. J. 82, 2269–2276 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by MEXT KAKENHI Grant Number 15H04818 (to M.H.), 15K09689 (to S.O.), and 15K19375 (to M.F.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.J. carried out the preparation of mutant plasmid, most part of the electrophysiological studies, data analysis and drafted the manuscript. O.S. carried out the genetic studies and helped to draft the manuscript. D.M. carried out part of the electrophysiological studies and helped to draft the manuscript. Q.W. and F.M. participated in the preparation of mutant plasmid. T.F. provided advice for the electrophysiological studies. M.T. collected the clinical data of the patient and gave advice on the experiment. Y.M. and S.H. gave medical treatment to the patient and participated to the critical revision of the paper. S.A. and A.T. participated to the critical revision of the article. H.M. conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ozawa, J., Ohno, S., Melgari, D. et al. Increased CaV1.2 late current by a CACNA1C p.R412M variant causes an atypical Timothy syndrome without syndactyly. Sci Rep 12, 18984 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23512-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23512-2

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.