Abstract

Lifestyle risk behaviours such as smoking, physical inactivity, and unhealthy diet account for a considerable disease burden globally. These risk behaviours tend to cluster within an individual, which could have detrimental health effects. In this study, we aimed to examine the clustering effect of lifestyle risk behaviours on cardiovascular disease (CVD) and CVD risk among adults in the United Kingdom (UK). We performed a latent class (LC) analysis with distal outcomes using the UK Biobank baseline (2006–2010) data. First, we estimated LC measurement models, followed by an auxiliary model conditional on LC variables. We reported continuous (mean difference—MD) and binary (odds ratio—OR) outcomes with 95% confidence intervals. We included 283,172 and 174,030 UK adults who had data on CVD and CVD risk, respectively. Multiple lifestyle risk behaviour clustering (physically inactive, poor fruit & vegetable intake, high alcohol intake, and prolonged sitting) had a 3.29 mean increase in CVD risk compared to high alcohol intake. In addition, adults with three risk behaviours (physically inactive, poor fruit & vegetable intake, and high alcohol intake) had 25.18 higher odds of having CVD than those with two risk behaviours (physically inactive, and poor fruit and vegetable intake). Social deprivation, gender and age were also associated with CVD. Individuals' LC membership with two or more lifestyle risk behaviours negatively affects CVD. Interventions targeting multiple lifestyle behaviours and social circumstances should be prioritized to reduce the CVD burden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) are responsible for 71% of all deaths worldwide1. Lifestyle risk behaviours such as smoking, physical inactivity, alcohol consumption, and unhealthy diet increase the risk of dying from NCD1. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs)1,2,3 account for most NCD deaths globally. In the UK, 11% of the population live with CVD, and CVD accounts for 25% of all deaths4. In 2010, the American Heart Association (AHA) recommended seven cardiovascular health behaviours (Life’s Simple 7) to reduce CVD morbidity and mortality in the general population, including smoking, diet, physical activity, body mass index, blood pressure, total cholesterol, and fasting glucose5. The 2019 AHA guideline on the primary prevention of CVD recommends that people engage in a healthy lifestyle throughout their life6.

Lifestyle risk behaviours, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, poor diet and physical inactivity are major risk factors for the development of CVD7,8. Physical inactivity and increased sedentary time are important modifiable risk factors for cardiometabolic disease9,10. Physical inactivity is also the fourth leading cause of disease and disability in the UK11. Sleeping too much or too little is also strongly associated with CVD12,13,14. People engaging in multiple risk behaviours tend to have poor health outcomes compared to those engaging in one risk behaviour15. Thus, identifying people with multiple risk behaviours provides insight into where policies should target to reduce inequalities in health16,17. While previous studies have investigated the clustering of lifestyle behaviours for people with CVD18,19 and the general population20, most did not include all major lifestyle behaviours, such as smoking, alcohol intake, fruit and vegetable consumption, physical activity, sitting behaviour, and sleep.

To analyse the co-occurrence of multiple health-related behaviours, different statistical approaches have been proposed in the literature21. However, these approaches are mainly focused on identifying clustering of risk behaviours and not estimating their effect on a distal outcome. Latent class (LC) analysis with a distal outcome is important for identifying how different lifestyle risk behaviours occur together among participants based on indicator variables, and to estimate the effect of LC membership on a distal outcome22,23,24. The effects of LC membership (clustering of lifestyle risk behaviours) on CVD and the risk of developing CVD have not yet been investigated. This study aimed to examine the prevalence of six lifestyle risk behaviours (smoking, poor fruit and vegetable consumption, alcohol intake, physical inactivity, prolonged sitting, and poor sleep), and clustering patterns of these lifestyle risk behaviours. In addition, we aimed to identify and estimate the effect of socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender), Townsend deprivation index and LC membership on CVD, and CVD risk.

Methods

UK Biobank has ethics approval from the North West Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee25. According to this approval, researchers do not require separate ethics applications. All participants provided written informed consent. This study was carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Study population

We analysed data from the UK Biobank study that included more than 500,000 middle-aged (38–73 years) adults recruited from 22 sites across England, Wales, and Scotland. We used baseline data collected between 2006 and 201026,27. Socio-demographic, lifestyle (smoking, alcohol consumption, dietary intake, physical activity, sitting time and sleep duration) and medical history were collected using the touchscreen questionnaire27.

Disease categories

The UK Biobank collected self-reported medical information, such as CVD based on physician diagnosis. To define participants' CVD status, we used data on vascular/heart problems diagnosed by a doctor (Field ID = 6150). Under this Field ID, four CVDs were reported: heart attack, angina, stroke, and high blood pressure. For this analysis, participants who were reported to have at least one of these diseases were classified as having CVD, not otherwise. A total of 283,172 participants without missing data were included.

For the 174,030 participants without CVD, we computed a 10-year CVD risk score28 using the Framingham risk score function from the CVrisk package29 in R30. The variables included in the 10-year CVD risk calculation were age, gender, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, blood pressure medication, smoking and diabetes status28.

Lifestyle behaviours

This analysis used six lifestyle behaviours: smoking, physical activity, fruit and vegetable consumption, alcohol intake, screen and driving time, and sleep duration.

Physical activity

The UK Biobank collected data on physical activity using adapted questions from the short International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)31 that includes the frequency, intensity and duration of walking, moderate and vigorous activity. UK Biobank data on time spent on moderate and vigorous activity was added and converted to a metabolic equivalent of task (MET) score. Participants were classified as active if they had ≥ 750 MET min/week or inactive (< 750 MET min/week), based on the 2019 AHA guideline6.

Fruit and vegetable intake

The UK Biobank collected data on dietary intake using the Food Frequency Questionnaire32. The NHS guideline recommends every individual to eat at least 5 portions of a variety of fruit and vegetables every day33,34. Data on fresh fruit (pieces), dried fruit (pieces), salad/raw vegetable (heaped tablespoons) and cooked vegetable (heaped tablespoons) were combined to calculate portions. Participants consuming at least 5 portions of fruits and vegetables per day were considered to have adequate fruit and vegetable intake.

Alcohol intake

Participants were asked for the number of pints of beer, glasses of wine, and measures of spirit consumed in the last week. Since alcoholic drinks differ in the amount of alcohol content, we converted each drink into equivalent standard units (1 unit contains 10 ml of ethyl alcohol)35. We calculated total weekly units of alcohol consumption by adding the units of beer, wine, and spirits. Based on the NHS guidelines35, we grouped participants as low-risk drinkers (≤ 14 units per week) or high-risk drinkers (> 14 units per week).

Smoking

To measure smoking status, participants were asked, "Do you smoke tobacco now?". Response options were “Yes, on most or all days”, “Only occasionally” and “No”. Those who responded “yes” or “smoke occasionally” were coded as 1, current smoker, while those who responded as “no” were coded as 0, not a current smoker.

Prolonged sitting

Total sitting time was calculated from the sum of self-reported hours spent watching television, using the computer, and driving during a typical day. Based on the estimated total sitting time, participants were categorized as low risk sitting (< 8 h/day) or prolonged sitting (≥ 8 h/day)36,37. This was based on the evidence of greater mortality risk for each increased sitting time category compared with < 8 h/day36,37.

Sleep duration

To measure sleep duration, the UK Biobank asked participants ‘About how many hours sleep do you get in every 24 h? (please include naps)’. Sleep duration was split using predefined thresholds from the literature; < 7 h, 7–8 h and > 8 h13. Based on these cut points, participants were grouped as having ‘poor sleep’ (< 7 or > 8 h/night) and ‘good sleep’ (7–8 h/night).

Socio-demographic variables

Socio-demographic characteristics (age and gender), and Townsend deprivation index (TSDI) were included in the latent class analysis (LCA) model. TSDI was used to measure participants' deprivation38. The index combines information on housing, employment, car availability and social class, with higher values indicating greater deprivation38.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed on socio-demographic characteristics, lifestyle behaviours and medical conditions. The Mplus version 8.8 software39 was used to estimate a distal outcome model to identify latent classes (LCs) of lifestyle risk behaviours, and the association between LC membership and distal outcomes (CVD, and CVD risk) (Fig. 1). To select the number of LCs that best fit the data, we first fitted a two-class latent model and successively increased the number of LCs by one, up to a six-class latent model. Model evaluation was performed using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and Akaike information criterion (AIC)40. Model selection was made based on statistical criteria (with lower AIC and BIC) and interpretability of the estimated LCs40. Based on these criteria, four LCs for CVD, and three LCs for CVD risk were selected (see Supplementary Tables).

LC analysis with a distal outcome22,23,24, covariate, and LC mediator41 was run to identify and estimate: (1) the effect of LC membership on distal outcomes (Fig. 1—left hand side), and (2) the direct, indirect (LC membership mediated effect) and total effect of covariate(s) on distal outcomes (Fig. 1—right hand side). Gender, age, and smoking were not used in the CVD risk distal outcome model—since we used them in the computation of the CVD risk score. For distal outcome models, the Bolck–Croon–Hagenaars (BCH) method22,42 outperforms other methods. In addition, the BCH approach gives more accurate mediation estimates in LC analysis mediation models41. The BCH method avoids shifts in LC in the final step and performs well when the variance of the auxiliary variable differs substantially across classes22. To estimate the model, the BCH method uses weights that reflect the measurement error of the LC variable22. Two versions of the BCH method were implemented in Mplus—the automatic and two-step manual BCH versions22. The automatic BCH method is restrictive. In this analysis, we used the manual BCH two-step approach to estimate auxiliary models with continuous (CVD risk) and categorical (CVD) distal outcomes. We estimated the LC measurement model and saved the BCH weights in the first step. The second step estimated the general auxiliary model conditional on the LC variable using the BCH weights. Continuous (mean difference—MD) and binary (odds ratio—OR) outcomes were reported with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Results

Population characteristics

We included UK adults who had data on CVD status (n = 283,172) and CVD risk (n = 174,030) along with lifestyle risk behaviours. The mean (SD) age of participants was 56.39 (8.02) and 55.15 (8.05) years for CVD and for those at risk of developing CVD, respectively. Among adults with CVD and at risk of developing CVD, 52.64% and 49.27% were males, respectively. Among adults with CVD, 67.29% had poor fruit and vegetable consumption, followed by high alcohol intake (64.83%) and were physically inactive (44.60%) (Fig. 2). Similarly, among adults at risk of developing CVD, 67.56% had poor fruit and vegetable intake and 63.54% had high alcohol intake (Fig. 3). Males, except for physical inactivity, had the highest proportion of lifestyle risk behaviours among those with CVD and at risk of developing CVD (see Supplementary Figs. S1, S2).

Lifestyle risk behaviours

A model with three LCs were selected for adults at risk of developing CVD and four LCs for CVD outcome data. For adults at risk of developing CVD, LC 1 was characterised by physical inactivity (53.70%), poor fruit and vegetable intake (83.00%), high alcohol intake (74.60%), and prolonged sitting (100.00%). Adults in LC 2 had a high probability of high alcohol intake (58.40%). LC 3 had high probabilities of poor fruit and vegetable intake (100.00%) and high alcohol intake (65.00%) (Table 1).

For the CVD outcome, adults in the LC 1 had a high probability of being physically inactive (61.60%), poor fruit and vegetable consumption (83.70%) and high alcohol intake (77.50%). Participants in LC 2 had a high probability of high alcohol intake (64.80%). In LC 3, the probability of having poor fruit and vegetable intake and high alcohol intake were 91.60% and 80.60%, respectively. The LC 4 was characterised by physically inactive (52.00%) and poor fruit and vegetable intake (73.40%) (Table 2).

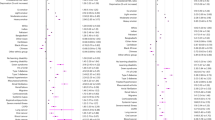

Effects of latent class membership on CVD risk

LC membership had a statistically significant effect on CVD risk. Being in LC 1 (physically inactive, poor fruit & vegetable intake, high alcohol intake, and prolonged sitting) was associated with increased CVD risk compared with LC 2 (MD = 3.29 [3.12, 3.46]). Similarly, adults in LC 3 (poor fruit & vegetable intake, and high alcohol intake) had a 0.89 mean increased CVD risk relative to LC 2 (Table 3). Similarly, social deprivation measured in TSDI, except for total effect, showed a statistically significant effect on CVD risk (Table 3).

Effects of latent class membership on CVD status

The odds of developing CVD were significantly associated with an individual’s LC membership. UK adults who belonged to LC 1 (Physically inactive, poor fruit and vegetable intake, and high alcohol intake) had 25.18 higher odds of having CVD than those in LC 4 (Physically inactive, and poor fruit and vegetable intake). Similarly, compared to those in LC 4, the odds of having CVD was higher among those who were in LC 2 (7.70) and LC 3 (5.19). In addition, gender, age and TSDI showed statistically significant effects on the odds of developing CVD. The direct, indirect, and total effects of being male were 1.19, 1.37- and 1.63-times higher odds of having CVD than females, respectively. A single-year increase in the age of adults, except for the indirect effect, was significantly associated with higher odds of developing CVD. For UK adults, a one-point increase in the TSDI score was associated with higher odds of having CVD (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that clustering of multiple lifestyle risk behaviours in adults significantly increased the risk of CVD and being diagnosed with CVD. Individuals’ latent class membership with two or more lifestyle risk behaviours were significantly associated with CVD risk and being diagnosed with CVD. Socioeconomic characteristics were also associated with being diagnosed with CVD.

The likelihood of developing CVD within a given time depends on the number of risk factors. Individuals' latent class membership with multiple lifestyle risk behaviours showed a 3.29 mean increase in the risk of developing CVD relative to a single risky behaviour. Smoking, physical inactivity, alcohol use, and low fruit and vegetable intake had the highest effect on NCD development and death8. On the other hand, lifestyle modification can reduce individuals’ risk of developing CVD. Adherence to Life's Simple 7 metrics has been associated with a lower rate of cardiovascular events43. In a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies on the effect of a combined healthy lifestyle (healthy diet, moderate alcohol consumption, non-smoking, physical activity, and optimal weight) on CVD risk, people with the highest number of healthy lifestyle factors had lower CVD risk relative to those with the lowest number of healthy lifestyle factors [pooled hazard ratio = 0.37 (95% CI 0.31–0.43)]44.

Clustering of two or more lifestyle risk behaviours could have a synergetic effect on CVD. Adults with clustering of three lifestyle risk behaviours (physically inactive, poor fruit and vegetable intake, and high alcohol intake) had 25.18 higher odds of having CVD than those with two lifestyle risk behaviours (physically inactive, and poor fruit and vegetable intake). In a systematic review of longitudinal observational studies, the combination of physical inactivity with smoking, high alcohol intake, poor diet, or sedentary behaviour showed increased CVD incidents, death due to CVD and/or any other cause45. However, smoking, and prolonged sitting did not show significant contributions to the LC membership and CVD status. It could be due to the small proportion, which needs further investigation.

Lifestyle risk behaviours are also associated with an increased risk of premature mortality. In a meta-analysis, years-of-life-lost due to high alcohol intake was 0.5 years, 2.4 years for physical inactivity, and 4·8 years for smoking46. In addition, the combination of multiple lifestyle risk behaviours showed increased risks of all-cause and/or cardiometabolic mortalities47,48. The co-occurrence of smoking, physical inactivity and poor social participation increased cardiometabolic mortality by 3.13 relative to no-risk behaviour47. On the contrary, meeting the cardiovascular health metrics and engaging in a healthy lifestyle were associated with lower incidences of CVD, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality49,50. Therefore, more emphasis should be placed on interventions targeting multiple lifestyle behaviours.

In addition, adults with increasing socioeconomic deprivation scores had an increased risk of being diagnosed with CVD. People living in socioeconomic deprived areas had multiple lifestyle risk behaviours, experience high CVD rates, and premature mortality46,51,52. In a study conducted in the UK, areas with higher socioeconomic deprivation had high coronary heart disease mortality53. Populations with socioeconomic deprivation are more likely to smoke, have a poor diet, and not exercise enough52. To reduce the effect of social deprivation on health, effective policies and strategies should be designed to modify socioeconomic circumstances and their consequences.

The odds of being diagnosed with CVD varied according to sex and age. In most cases, male and a single-year increase in the age of adults were significantly associated with the odds of being diagnosed with CVD. In a study conducted on gender-specific, lifestyle-related behaviours and 10-year CVD risk, males had higher CVD events—both first and recurrent CVD relative to females54. Regarding the effect of age, a meta-analysis reported that the hazard ratio of CVD increased with increasing age of adults44. Younger adults have more cardiovascular benefits from the combined effects of a healthy lifestyle44,50. Therefore, lifestyle interventions targeted towards younger people are needed to prevent CVD.

Our study has several strengths. LCA, a cross-sectional latent variable mixture modelling, has several advantages over other traditional methods used in lifestyle risk behaviour55,56. First, it uses maximum likelihood estimation to identify subgroups that are internally homogenous and externally heterogeneous57. Second, it is a model-based technique, which has an advantage over heuristic cluster techniques (e.g., k-means clustering) in that it provides fit statistics40. Fit statistics are useful in selecting the most appropriate model for the data58 and to compare models for hypothesis testing59. Third, LCA provides information on the probability that an individual is within a particular class58. This has significant importance for researchers and practitioners in the field to identify subgroups of lifestyle risk behaviours and a targeted approach to healthy lifestyle promotion. These subgroups can be studied further to investigate problems related to lifestyle risk behaviour classes that are commonly found in the general population, how prevalent they are, what causes them, what future outcomes they predict (distal outcomes), and whether lifestyle risk behaviour classes change over time.

Despite these strengths, our findings should be considered with the following limitations in mind. First, lifestyle risk behaviours were measured based on self-reported questionnaires, which could have recall bias or social desirability bias. Second, the measures of several lifestyle risk behaviours are under-specified; for example, the sleep measure was limited quantity only, without considering sleep quality. The smoking measure also did not consider past smoking.

Conclusion

Latent class membership with two or more lifestyle risk behaviours showed an increased risk of developing CVD and CVD events due to the potential synergetic relationships among lifestyle risk factors. Deprived populations are more likely to be affected by CVD from the wide combination of lifestyle risk behaviours. Early interventions targeting multiple lifestyle risk behaviours from young age should be prioritized to prevent future CVD events.

Data availability

All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

References

Forouzanfar, M. H. et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. The Lancet 388(10053), 1659–1724 (2016).

Vos, T. et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. The Lancet 396(10258), 1204–1222 (2020).

Kyu, H. H. et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 359 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. The Lancet 392(10159), 1859–1922 (2018).

Heart Statistics. BHF Statistics Factsheet: UK. https://www.bhf.org.uk/what-we-do/our-research/heart-statistics.

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: The American Heart Association’s strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation 121(4), 586–613 (2010).

Arnett, D. K. et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 74(10), e177–e232 (2019).

Lee, I.-M. et al. Group LPASW: Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. The Lancet 380(9838), 219–229 (2012).

World Health Organization. Global Health Risks: Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks (World Health Organization, 2009).

Grøntved, A. & Hu, F. B. Television viewing and risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis. JAMA 305(23), 2448–2455 (2011).

Bell, J. A. et al. Combined effect of physical activity and leisure time sitting on long-term risk of incident obesity and metabolic risk factor clustering. Diabetologia 57(10), 2048–2056 (2014).

Murray, C. J. et al. UK health performance: Findings of the global burden of disease study 2010. The Lancet 381(9871), 997–1020 (2013).

Covassin, N. & Singh, P. Sleep duration and cardiovascular disease risk: Epidemiologic and experimental evidence. Sleep Med. Clin. 11(1), 81–89 (2016).

Kuehn, B. M. Sleep Duration Linked to Cardiovascular Disease (American Heart Association, 2019).

Nagai, M., Hoshide, S. & Kario, K. Sleep duration as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease: A review of the recent literature. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 6, 54–61 (2010).

Hart, C. L., Smith, G. D., Gruer, L. & Watt, G. C. The combined effect of smoking tobacco and drinking alcohol on cause-specific mortality: A 30 year cohort study. BMC Public Health 10(1), 1–11 (2010).

Behrens, G. et al. Healthy lifestyle behaviors and decreased risk of mortality in a large prospective study of US women and men. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 28(5), 361–372 (2013).

Ford, E. S., Bergmann, M. M., Boeing, H., Li, C. & Capewell, S. Healthy lifestyle behaviors and all-cause mortality among adults in the United States. Prev. Med. 55(1), 23–27 (2012).

Cassidy, S., Chau, J. Y., Catt, M., Bauman, A. & Trenell, M. I. Cross-sectional study of diet, physical activity, television viewing and sleep duration in 233 110 adults from the UK Biobank; the behavioural phenotype of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open 6(3), e010038 (2016).

Said, M. A., Verweij, N. & van der Harst, P. Associations of combined genetic and lifestyle risks with incident cardiovascular disease and diabetes in the UK Biobank Study. JAMA Cardiol 3(8), 693–702 (2018).

Birch, J. et al. Clustering of behavioural risk factors for health in UK adults in 2016: A cross-sectional survey. J. Public Health 41(3), e226–e236 (2019).

McAloney, K., Graham, H., Law, C. & Platt, L. A scoping review of statistical approaches to the analysis of multiple health-related behaviours. Prev. Med. 56(6), 365–371 (2013).

Asparouhov, T. & Muthén, B. Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Using the BCH method in Mplus to estimate a distal outcome model and an arbitrary secondary model. Mplus Web Notes 21(2), 1–22 (2014).

Bakk, Z., Tekle, F. B. & Vermunt, J. K. Estimating the association between latent class membership and external variables using bias-adjusted three-step approaches. Sociol. Methodol. 43(1), 272–311 (2013).

Bakk, Z. & Kuha, J. Relating latent class membership to external variables: An overview. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 74(2), 340–362 (2021).

UK Biobank Research Ethics Approval. https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/learn-more-about-uk-biobank/about-us/ethics.

UK Biobank: A Large Scale Prospective Epidemiological Resource. https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/media/gnkeyh2q/study-rationale.pdf.

Sudlow, C. et al. UK biobank: An open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 12(3), e1001779 (2015).

D’Agostino, R. B. Sr. et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 117(6), 743–753 (2008).

Victor Castro. CVrisk: Compute Risk Scores for Cardiovascular Diseases. R package version 1.1.0 (2021).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2022).

Craig, C. L. et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 35(8), 1381–1395 (2003).

Willett, W. C. et al. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am. J. Epidemiol. 122(1), 51–65 (1985).

The Eatwell Guide Booklet. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-eatwell-guide.

5 A Day Portion Sizes: NHS Choices. https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/5-a-day-portion-sizes/.

NHS. Alcohol Units. https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/alcohol-support/calculating-alcohol-units/.

Van der Ploeg, H. P., Chey, T., Korda, R. J., Banks, E. & Bauman, A. Sitting time and all-cause mortality risk in 222 497 Australian adults. Arch. Intern. Med. 172(6), 494–500 (2012).

Henschel, B., Gorczyca, A. M. & Chomistek, A. K. Time spent sitting as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 14(2), 204–215 (2020).

Yousaf, S. & Bonsall, A. UK Townsend Deprivation Scores from 2011 census data (UK Data Service, 2017).

Muthén, L. K. & Muthén, B. O. Mplus User’s Guide 8th edn. (Muthén & Muthén, 2022).

Weller, B. E., Bowen, N. K. & Faubert, S. J. Latent class analysis: A guide to best practice. J. Black Psychol. 46(4), 287–311 (2020).

Hsiao, Y.-Y. et al. Latent class mediation: A comparison of six approaches. Multivar. Behav. Res. 56(4), 543–557 (2021).

Nylund-Gibson, K., Grimm, R. P. & Masyn, K. E. Prediction from latent classes: A demonstration of different approaches to include distal outcomes in mixture models. Struct. Equ. Modeling 26(6), 967–985 (2019).

Díez-Espino, J. et al. Impact of life’s simple 7 on the incidence of major cardiovascular events in high-risk Spanish adults in the PREDIMED study cohort. Rev. Española Cardiol. 73(3), 205–211 (2020).

Tsai, M.-C., Lee, C.-C., Liu, S.-C., Tseng, P.-J. & Chien, K.-L. Combined healthy lifestyle factors are more beneficial in reducing cardiovascular disease in younger adults: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 1–10 (2020).

Lacombe, J., Armstrong, M. E., Wright, F. L. & Foster, C. The impact of physical activity and an additional behavioural risk factor on cardiovascular disease, cancer and all-cause mortality: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 19(1), 1–16 (2019).

Stringhini, S. et al. Socioeconomic status and the 25 × 25 risk factors as determinants of premature mortality: a multicohort study and meta-analysis of 17 million men and women. The Lancet 389(10075), 1229–1237 (2017).

Krokstad, S. et al. Multiple lifestyle behaviours and mortality, findings from a large population-based Norwegian cohort study: The HUNT Study. BMC Public Health 17(1), 1–8 (2017).

Ding, D., Rogers, K., van der Ploeg, H., Stamatakis, E. & Bauman, A. E. Traditional and emerging lifestyle risk behaviors and all-cause mortality in middle-aged and older adults: Evidence from a large population-based Australian cohort. PLoS Med. 12(12), e1001917 (2015).

Michos, E. D. & Khan, S. S. Further understanding of ideal cardiovascular health score metrics and cardiovascular disease. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 19(7), 607–617 (2021).

Tsai, M.-C. et al. Comparison of four healthy lifestyle scores for predicting cardiovascular events in a national cohort study. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 1–11 (2021).

Schultz, W. M. et al. Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular outcomes: Challenges and interventions. Circulation 137(20), 2166–2178 (2018).

Foster, H. M. et al. The effect of socioeconomic deprivation on the association between an extended measurement of unhealthy lifestyle factors and health outcomes: A prospective analysis of the UK Biobank cohort. Lancet Public Health 3(12), e576–e585 (2018).

Theocharidou, L. & Mulvey, M. R. The effect of deprivation on coronary heart disease mortality rate. Biosci. Horiz. 11, 007 (2018).

Kouvari, M. et al. Gender-specific, lifestyle-related factors and 10-year cardiovascular disease risk; the ATTICA and GREECS cohort studies. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 17(4), 401–410 (2019).

Dumith, S. C., Muniz, L. C., Tassitano, R. M., Hallal, P. C. & Menezes, A. M. Clustering of risk factors for chronic diseases among adolescents from Southern Brazil. Prev. Med. 54(6), 393–396 (2012).

Schuit, A. J., van Loon, A. J. M., Tijhuis, M. & Ocké, M. C. Clustering of lifestyle risk factors in a general adult population. Prev. Med. 35(3), 219–224 (2002).

Berlin, K. S., Williams, N. A. & Parra, G. R. An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 1): Overview and cross-sectional latent class and latent profile analyses. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 39(2), 174–187 (2014).

Vermunt, J. & Magidson, J. Latent Class Cluster Analysis (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Miettunen, J., Nordström, T., Kaakinen, M. & Ahmed, A. Latent variable mixture modeling in psychiatric research–a review and application. Psychol. Med. 46(3), 457–467 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the UK Biobank for providing access to the data and Deakin University for creating the platform to access the data. We also thank Gavin Abbott and Katherine Livingstone for their help in facilitating and guiding us with UK Biobank registration and in accessing the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.K.T., S.M.S.I. and R.M. conceptualized the design of the latent class analysis with the distal outcome. T.K.T. performed the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. T.K.T., S.M.S.I. and R.M. have participated in critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read, provided feedback, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tegegne, T.K., Islam, S.M.S. & Maddison, R. Effects of lifestyle risk behaviour clustering on cardiovascular disease among UK adults: latent class analysis with distal outcomes. Sci Rep 12, 17349 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22469-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22469-6

This article is cited by

-

How are different clusters of physical activity, sedentary, sleep, smoking, alcohol, and dietary behaviors associated with cardiometabolic health in older adults? A cross-sectional latent class analysis

Journal of Activity, Sedentary and Sleep Behaviors (2023)

-

Association between latent profile of dietary intake and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs): Results from Fasa Adults Cohort Study (FACS)

Scientific Reports (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.