Abstract

Smoking is a leading risk factor for many of the top ten causes of death worldwide. Of the 1.3 billion smokers globally, 80% live in low- and middle-income countries, where the number of deaths due to tobacco use is expected to double in the next decade according to the World Health Organization. Genetic studies have helped to identify biological pathways for smoking behaviours, but have mostly focussed on individuals of European ancestry or living in either North America or Europe. We performed a genome-wide association study of two smoking behaviour traits in 10,558 men of African ancestry living in five African countries and the UK. Eight independent variants were associated with either smoking initiation or cessation at P-value < 5 × 10–6, four being monomorphic or rare in European populations. Gene prioritisation strategy highlighted five genes, including SEMA6D, previously described as associated with several smoking behaviour traits. These results confirm the importance of analysing underrepresented populations in genetic epidemiology, and the urgent need for larger genomic studies to boost discovery power to better understand smoking behaviours, as well as many other traits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Smoking is a leading risk factor for many of the top ten causes of death worldwide, including heart and lung diseases1. Each year, tobacco use is directly responsible for 7 million deaths and 25% of all cancer fatalities globally2. However, smoking prevalence varies among world regions, and of the 1.3 billion tobacco users worldwide, 80% live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)3.

Reassuringly, prediction models by the World Health Organization (WHO) show a reduction in smoking prevalence in most areas from 2010 to 2025 thanks to tobacco control strategies4,5. However, in parallel to this decline in American and European populations, the tobacco industry and market has recently expanded in Africa, due to the fast population growth and the improvement in buying power6. In line with this, sub-Saharan Africa has experienced a 52% increase in tobacco use from 1980 to 20167 and a further 9 million people are expected to take up smoking in the African region by 20258. In addition, the support for smokers wishing to quit and training for healthcare professionals in smoking cessation is still very limited across the continent9. To help counteract these changes, as of November 2018, over forty African countries supported the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and twenty were involved in the Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products6.

Currently, there are 94 million male and 13 million female tobacco users in Africa, with one in five adolescents using tobacco, and an increasing prevalence of smoking among young women6. The type of tobacco used varies among countries and sexes, and its consumption has been associated with alcohol drinking, lower income status, education levels, and professional activity10,11. Using Demographic Health Surveys data for 30 sub-Saharan African countries, Sreeramareddy et al. compared smoking with the use of smokeless tobacco and showed that while the first is more prevalent among men, the majority of women preferentially uses the second, and more specifically chewing tobacco10. Similar patterns were confirmed by a recent study focusing on tobacco and alcohol use in rural and urban settings in four sub-Saharan African countries11.

Tobacco use patterns are different when we focus on communities of African descent in the UK. In 2019, 14% of adults in the UK smoked regularly, with differences between men and women (15.9% and 12.5%, respectively), resulting in a ratio of men to women smoking prevalence of 1.27. In the same year, among the 9.6% of Black ethnic minorities in the UK who smoked, this ratio was 1.8712. However, contrary to the rise in tobacco use in continental Africa, smoking prevalence among Black adults in the UK decreased from 13.3 to 9.6% between 2014 and 201912.

In the US, African-American (AA) individuals have been shown, on average, to start smoking later and smoke fewer cigarettes per day than European-American individuals13. However, they show comparable levels of nicotine equivalents, are less likely to successfully quit smoking, and have a higher risk of smoking-related lung cancer13,14.

Genetic factors have been shown to play a role in smoking behaviour traits. Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) identify genetic variants associated with the trait of interest, which inform biological understanding and highlight functional pathways and potential drug targets for precision medicine approaches to treatment15. The strongest associations with smoking behaviours have been consistently shown at locus 15q25.1, containing the cluster of CHRNA5-A3-B4 genes which encode subunits of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), for both amount smoked and nicotine dependence16. In the brain, nicotine binds to nAChRs stimulating the release of several neurotransmitters, impacting the reward pathway, learning and memory16. To date, the largest GWAS of smoking behaviour traits included 1.2 million individuals and highlighted genes which encode proteins involved in neurotransmission of nicotine, dopamine and glutamate17. However, as in most GWASs, it only includes individuals of European ancestry failing on the representation of global human diversity18,19.

Previous genetic epidemiology studies of smoking behaviours in individuals of African descent have only included AA participants and identified six genetic variants associated with different traits. In the Study of Tobacco in Minority Populations (n = 32,389 AA individuals) only one variant, rs2036527 on chromosome (chr) 15, ~ 6 kb from the 5’ of CHRNA5, was associated with cigarettes smoked per day13. In another study including ~ 1000 AA participants, Chenoweth et al. found three independent variants on chr 19 (rs12459249, rs111645190, rs185430475) associated with nicotine metabolite ratio (NMR)14. These variants showed low linkage disequilibrium with four signals previously identified in a Finnish cohort and located in the genomic region of the CYP2A6 gene which encodes the key enzyme of nicotine metabolism14,16. Hancock et al. performed a trans-ethnic analysis including 28,677 European and 9,925 AA smokers, and identified variant rs910083 on chr 20 as associated with nicotine dependence20. Finally, Xu et al. studied smoking trajectories in almost 300,000 individuals from the Million Veteran Program (MVP), including > 54,000 AAs, which aimed to capture the variation of smoking status over time21. They found an association on chr 1 with variant rs4478781 in AAs only, and 14 associated loci in a trans-ethnic meta-analysis including European-Americans and Hispanic-Americans, mainly driven by the results from the European ancestry group21.

Despite these interesting findings, individuals of African descent, and especially those living in continental Africa, remain heavily underrepresented in large-scale genetic studies18,19. Here we present the first GWAS of smoking behaviour traits in 10,558 men of African ancestry living in five African countries and the UK. Because of the sex biases in smoking behaviour and the low smoking prevalence in women (ranging between 0.5% and 7%) in the African datasets included here10,11, we decided that the study would be less biased if women were excluded from all discovery analyses. This was important as we included African ancestry individuals living in Africa and the UK, with different cultural influences that affected the prevalence of smoking among women, but not men.

Materials and methods

Participants

This study used genetic data and smoking behaviour information from three different cohorts: the Africa Wits-INDEPTH Partnership for Genomic Studies (AWI-Gen)22, the Uganda Genome Resource23(UGR) and the individuals of African ancestry in UK Biobank (UKB-AFR)24.

AWI-Gen is a cross-sectional population study including ~ 12,000 individuals from Ghana, Burkina Faso, Kenya and South Africa, aged 40–60 + years, aimed at understanding the genomic and environmental factors that contribute to body composition and cardio-metabolic diseases. For the purpose of this study, with the aim of accounting for the local population structure, the AWI-Gen cohort was divided into three datasets representing three geographical areas: AWI-East (Kenya), AWI-South (South Africa) and AWI-West (Ghana and Burkina Faso).

The UGR includes ~ 6,400 individuals, and it is a subset of the General Population Cohort (GPC)25, a population-based open cohort aimed at understanding HIV infections in Uganda. The UGR was built with the aim of improving local resources for public health and to allow large genetic epidemiology studies23.

UKB is a large longitudinal study in the UK which includes samples from over 500,000 volunteers aged 40–69 years at baseline24. Since 2006, it has collected extensive phenotypic and biological data to allow approved researchers to investigate the genetic and/or environmental determinants of a wide range of diseases and health-related phenotypes. Using genetic data for population stratification, we identified ~ 7,800 individuals of African ancestry in UKB26.

Description of phenotypes

We have analysed two binary smoking behaviour traits: Smoking Initiation (SI) and Smoking Cessation (SC), defined using relevant answers in questionnaire data available in each cohort. Overall, SI compares ‘never’ smokers (controls) versus ‘ever’ smokers (cases), in which the former represents individuals who have never, or only very rarely, smoked in their life and the latter are participants who smoked or currently smoke every day or occasionally. SC only includes ‘ever’ smokers and it compares ‘current’ smokers (cases), who were smoking every day or occasionally at the time of answering the questionnaire, to ‘previous’ smokers (controls), who were not. The detailed description of the phenotype definitions and the specific questions used for each cohort are available in Supplementary Note 1.

The number of cases and controls for each phenotype in each cohort is presented in Table 1; we reported the sample sizes for females in Supplementary Table 1.

Genotyping and imputation quality control

The AWI-Gen individuals were genotyped at ~ 2.4 M SNPs using the Illumina Infinium H3Africa SNP array, which is designed to be specific and sensitive to the genomic diversity of African populations22. Imputation at ~ 39 M autosomal variants was performed using the Haplotype Reference Consortium (HRC) panel27 on the Michigan Imputation Server. Details of quality control (QC) and imputation settings are presented in Choudhury et al. 202028.

The UGR individuals were genotyped at ~ 2.2 M autosomal markers using the HumanOmni2.5-8 chip array. Imputation at ~ 98 M variants was performed using a combined reference panel with sequence data from three different studies (African Genome Variation Project29, Uganda 2000 Genomes and 1000 Genomes Project Phase 3 [1000GP]30). Details of QC and imputation settings are presented in Gurdasani et al.23.

UK Biobank individuals were genotyped at ~ 800,000 variants using the UK Biobank Axiom Array. Imputation at ~ 93 M autosomal variants was performed using the HRC27, the UK10K31 and the 1000 GP30 reference panels combined. Details of QC and imputation settings are presented in Bycroft et al.24.

Details of genotyping QC are reported in Supplementary Table 2. Additional QC was performed across all datasets to ensure that effect alleles were consistently aligned between cohorts. Imputed autosomal variants with a minor allele count (MAC) ≥ 20 or minor allele frequency (MAF) > 0.01, and an imputation info score ≥ 0.3 were included in all further analyses (Supplementary Fig. 1).

In order to compare population structure among the cohorts we have performed a principal components analysis (PCA) with smartpca32 for each cohort including the African populations from the 1000GP30. The variant QC for this analysis and the calculation of the PCs loadings were performed on the 1000GP populations only, using the same parameters reported in Supplementary Table 2 in order to allow comparison among the plots (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Study level genome-wide association analyses

Genome-wide association analyses were performed using a univariate linear mixed model (LMM) and significance was evaluated using a likelihood ratio test as implemented in GEMMA v0.98.133. Covariates included age, age squared and as many principal components (PCs) as required in each dataset (AWI-East 5PCs; AWI-South 14PCs; AWI-West 11PCs; UGR 10PCs; UKB-AFR 9PCs). PCs were calculated for each dataset from a PC analysis using independent genotyped SNPs in PLINK v1.9034. For AWI-Gen and UKB-AFR datasets, we determined the number of PCs to include by using the eigenvalues to assess when adding further components would not contribute additional information. In an iterative process, we stopped at the first PC for which the contribution of the three previous PCs was not greater than the contribution of the following three (Supplementary Fig. 3). For UGR, 10 PCs were used as in Gurdasani et al.23. The genetic relatedness matrix (GRM) included in the LMM was calculated for each full cohort with GEMMA v0.98.133 using independent SNPs. Details of the QC used for genotyped variants and the number of variants used to perform the PCA and to calculate the GRM for each cohort are reported in Supplementary Table 2. Manhattan and quantile–quantile (qq-) plots were visualised using the qqman package in R35. The LD score regression intercept was calculated to assess the presence of genomic inflation using ldsc v1.0.136. LD scores were calculated including the African superpopulation from 1000GP30. When the LD score intercept was above 1.05, the association P-value was recalculated as follows: \(corrected.se=se*\surd (LDScoreregressionintercept)\); \(z=-|\frac{estimate}{corrected.se}|\); \(corrected.pvalue=P(Z<-z)+P(Z>z)\). Where \(corrected.se\) and \(se\) are the corrected and original standard error of the estimate effect size respectively; \(z\) is the z-score used to calculate the corrected P-value using two-sided test statistics.

Meta-analysis

We performed a two-step meta-analysis. In step1, we included the three AWI-Gen datasets (AWI-East, AWI-South, AWI-West) to obtain AWI-Gen cohort-level summary statistics. In step2, we included AWI-Gen, UGR and UKB-AFR. In each step, we used the modified random effect model (RE2) as implemented in METASOFT37. Variants were included in the analysis if they were present in at least two out of three studies. Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the number of variants for each meta-analysis and phenotype. Results were visualised using Manhattan and qq-plots, and LD score regression intercept was calculated to evaluate genomic inflation, as done for the study-level association analyses.

Definition of associated and sentinel variants

For each trait, variants were divided into three tiers defined using different significance thresholds which take into account the results of the meta-analysis and the cohort-level summary statistics (AWI-Gen, UGR and UKB-AFR). Tier1 included variants with meta-analysis P-value < 5 × 10–8 and P-value < 0.05 in each cohort; tier2, variants with a meta-analysis P-value < 5 × 10–6 and P-value < 0.05 in each cohort; tier3, variants with a P-value < 5 × 10–8 in at least one of the cohort genome-wide association analyses.

For each tier, sentinel variants were defined in an iterative process as the variants with the lowest P-value in a region of 200 kb centered on the variant.

Conditional analysis

To assess the presence of any additional independent signals, we utilized the GCTA v1.93.238 stepwise model selection for the conditional analysis (option –vcojo-slct) in a region of + /- 100 kb from each sentinel variant and using the populations of African ancestry in 1000GP30 as a reference for LD patterns.

Fine-mapping analysis

Regions of + /- 100 kb from each sentinel variant were analysed to retrieve the 99% credible set variants using FINEMAP v1.4 software39 with a shotgun stochastic algorithm assuming one causal variant. The shotgun stochastic search algorithm uses iterations and random picking: at each round a causal configuration is chosen and slightly modified to create a pool of ‘nearby’ casual configurations with comparable or better posterior probability. This is saved for memory efficiency and from this pool the algorithm stochastically chooses one as starting causal configuration for the following iteration39.

We then created the refined credible sets by filtering for a Posterior Inclusion Probability (PIP) greater than or equal to 1%. LD proxy variants of these SNPs were identified in the African populations in 1000GP30 within the regions defined by the 99% credible sets extended by ± 100 kb using PLINK v1.9034. Variants with both D’ ≥ 0.9 and r2 ≥ 0.6 were retained. Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 3 show the 99% credible sets, the refined credible sets and the proxy variants for each locus. The refined credible set variants and their proxies were used for all follow up analyses.

Replication and lookup analyses

The replication of our meta-analysis step2 results was performed using two publicly available datasets: (a) the genome-wide summary statistics for smoking trajectories in individuals of African ancestry included in the MVP21; (b) and the genome-wide summary statistics from the SI and SC meta-analyses in individuals of European ancestry released by the GWAS & Sequencing Consortium of Alcohol and Nicotine use (GSCAN)17. The number of independent sentinel variants was used to calculate the Bonferroni corrected P-value threshold for the replication analyses (0.007 SI; 0.05 SC).

We performed two lookup analyses aiming to understand if our discovered loci were previously described as associated with any smoking phenotypes or any other trait.

For the first analysis, we compiled a list of variants described in 14 studies13,17,20,21,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49 as associated with 9 smoking behaviour traits (Smoking Initiation; Smoking Cessation; Age of Initiation; Cigarettes per Day; Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence; Pack Years; Trajectory Contrast I; Trajectory Contrast II; Time to the First Cigarette).

For the second analysis, we queried GWAS Catalog v1.0.250 (see URLs) to identify variants associated with any other phenotype.

Follow up analyses

Gene prioritisation

We combined results from four analyses in order to identify the genes influenced by the SNPs in the refined credible sets and their proxies. First, we assessed the predicted pathogenicity of the variants using the Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) score51 as implemented in the Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor (VEP)52. We defined as pathogenic those variants with a CADD score greater than or equal to 15.

We then investigated if the variants influenced the expression of a gene or the protein level using eQTL and pQTL data respectively. We used the eQTL Mapping option in the Functional Mapping and Annotation of Genome-Wide Association Studies (FUMA) v1.3.653 which collects eQTL data from 14 data sources (see URLs). Significant eQTLs are defined on either P-value or FDR thresholds based on the specific data source (see URLs) and we retrieved results from blood, brain or lung tissues. For the pQTL analysis, we used data from 90 cardiovascular genes of the SCALLOP Consortium54 and followed their definition of significant pQTLs. They defined signals more than 1 Mb away from the protein encoding gene as trans-pQTLs, and signals that were closer than 1 Mb as cis-pQTLs54.

Finally, we used the Chromatin Interaction Mapping tool as implemented in FUMA v1.3.653 to gain insights into possible epigenetic properties of the interrogated variants using the blood, brain and lung tissues (see URLs).

We selected those variants that were identified by at least one of the analyses described above and retrieved the list of prioritised genes for SI and SC.

Pathway analysis

The prioritised genes were queried to investigate biological function and potential implication in smoking behaviour using the webtool Metascape55 which performs pathway enrichment and protein–protein interaction analyses combining information from different databases and -omics data using hierarchical clustering55. Pathway enrichment is based on an overrepresentation analysis55, while the protein–protein interaction makes use of the MCODE algorithm56, which captures densely connected regions in a complex network55,56. For both analyses, we used the default option of Metascape and the Entrez Gene ID as gene name. We considered a pathway being enriched if represented by prioritised genes linked to distinct meta-analysis step2 associated loci.

PheWAS analysis

Variants in the refined credible set for the locus of chr 15 and passing at least one of the criteria for our gene prioritisation strategy were included in a PheWAS using the PheWAS R package57 in three datasets available from the Integrative Epidemiology Unit (IEU) OpenGWAS project (see URLs)58,59: (i) ‘IEU analysis of UK Biobank phenotypes’60 (ukb-b, see URLs) and (ii) ‘Neale lab analysis of UK Biobank phenotypes, round 2’ (ukb-d, see URLs) for European individuals, and (iii) ‘Pan-ancestry genetic analysis of the UK Biobank performed at the Broad Institute’61 (ukb-e, see URLs) for African individuals only. PheWAS results from ukb-b and ukb-d were combined together since they include distinct phenotypes and refer to the same ancestry group. For each ancestry group we filtered for significant associations after applying a Bonferroni correction for each variant based on the number of tested phenotypes.

Ethics approvals

The AWI-Gen study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) of the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) (protocol numbers M121029 and M170880). In addition, each research site obtained approval from their local ethics review board prior to commencing any participant-related activities. Uganda Genome Resource was approved by the Science and Ethics Committee of the UVRI, the Ugandan National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST #SS 4283), and the East of England-Cambridge South NHS Research Ethics Committee United Kingdom. This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under approved Application 4892. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and all research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Discovery analyses

We performed a genome-wide association analysis for each dataset and phenotype combination in a total of 10,558 men for SI and 4,257 for SC. A modified random effect model was implemented for both steps of the meta-analysis on variants present in at least two of the individual datasets. Step1 included the three AWI-Gen datasets and step2 meta-analysed the results of step1 with UGR and UKB-AFR (Supplementary Fig. 1). Results for the individual studies and meta-analysis step1 are presented in Supplementary Note 2.

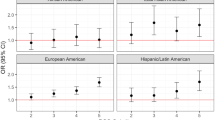

For SI, step2 analysed 14,459,454 SNPs: no genome-wide significant variant was observed, while 99 variants passed the suggestive significance threshold (Fig. 1a). The qq-plot showed no residual population structure (Supplementary Fig. 4a) and the LD score regression intercept was 0.94. For SC, step2 analysed a total of 14,057,868 variants: no SNPs passed the genome-wide significant threshold and 45 SNPs were below the suggestive significance threshold (Fig. 1b). The qq-plot showed no residual population structure (Supplementary Fig. 4b), confirmed by an LD-score regression intercept value of 0.88. Following our tier criteria and our definition of sentinel variants, we identify (i) no variant in tier1 for either trait; (ii) 7 sentinel variants for SI and one for SC in tier2; and (iii) one variant in tier3 for SI (rs114033989 in UGR). In the meta-analysis, the 8 sentinel variants from tier2 show low heterogeneity (I2) of effect sizes, as well as having a consistent direction of effect among studies and an imputation info score ranging 0.82–0.99 in all cohorts (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 5). We focused our follow up analyses on the sentinel variants in tier2.

Manhattan plots of step2 GWAS meta-analysis: (a) smoking initiation, (b) smoking cessation; continuous line, suggestive p-value (P) significance threshold (5 × 10–6); dashed line, genome-wide significance threshold (5 × 10–8). Number of participants and variants analysed is reported in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Conditional analyses did not identify any additional independent signals in the 200 kb loci we defined around our 8 sentinel variants in tier2. For each locus, we first identified the 99% credible set with a Bayesian approach, which included a total of 2,243 potentially causal variants for SI and 120 for SC (Supplementary Table 3). These 99% credible sets spanned regions of 47.6 to ~ 200 kb (see Supplementary Fig. 6), with the only exception of the 99% credible set being on chr 19 which included only one variant. We then identified the refined credible sets to include only those variants with a PIP > 0.01 and their LD proxies (D’ ≥ 0.9 and r2 ≥ 0.6) reducing the number of SNPs to 136 for SI and 36 for SC (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 3).

Replication and literature lookup analyses

We performed replication analyses using the refined credible sets and their proxy variants in two different datasets: (a) an analysis of smoking trajectory contrasts performed in individuals of African ancestry21; and (b) two meta-analyses of SI and SC in European individuals17. The smoking trajectory contrasts represent a comparison of either (I) current vs never or (II) current vs mixed smokers, defined using electronic health records data, and capturing SI and SC respectively21.

When using dataset (a)21, 9 out of the 69 variants in the refined credible set on chr 15 passed the Bonferroni corrected threshold for SI (Supplementary Table 4a). Four out of 5 variants on chr 1 passed the nominal significance threshold, and no variants on chr 10 showed evidence of replication. No dataset (a) variants were found for the loci on chr 4, 7, 16 and 19. When using (b)17, all the variants in the refined credible set on chr 15 passed the Bonferroni corrected threshold for SI, with four of these being genome-wide significant and having the same direction of effect as in our analysis (Supplementary Table 4b). No variants on chr 7, 16 and 19 showed evidence of replication for SI or SC and no dataset (b) variants were found for the loci on chr 1, 4 and 10.

We investigated if any of the variants included in the credible sets had been previously described as associated with any smoking behaviour trait or any other phenotype. From both analyses, we only obtained results for the SI trait. One variant on chr 15 (rs9646181) was previously described as associated with smoking trajectory contrast I (P-value 4.8 × 10–10) (Supplementary Table 4c), in a trans-ethnic meta-analysis including individuals of African, European and Hispanic ancestries and it was mapped as an intronic variant in the gene SEMA6D21. Looking beyond smoking behaviour traits, we interrogated the GWAS Catalog and found that the variant rs4624724 on chr 4 had been previously described as associated with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (P-value 4 × 10–8; Supplementary Table 4d)62.

Functional follow up analyses

Gene prioritisation analyses

In our gene prioritisation strategy we combined the results of four different analyses: variant annotation with VEP and its CADD score estimate, eQTL and pQTL mapping, and chromatin interaction mapping.

For both traits, all queried variants were annotated as non-coding, or as part of upstream or downstream regulatory regions (VEP52) and no variants were identified as a pQTL using the 90 cardiovascular proteins of the SCALLOP Consortium54.

For SI, we retrieved a total of 95 genes. Specifically, the CADD scores highlighted a total of six possible deleterious variants affecting two genes, RP11-552E10.1 and SEMA6D (Supplementary Table 5a). The eQTL mapping showed that 6 variants affect the expression of 4 genes (AC073133.1, FBN1, MAN2B2 and SLC1A6) in different brain tissue datasets (BRAINEAC (see URLs), Common Mind Consortium63, eQTLGen64, PsychENCODE65; Supplementary Table 5a). Finally, the chromatin interaction analysis highlighted 42 unique variants, at least one for each associated locus, having an effect on a total of 92 genes in either brain tissues or lung fibroblast cells65,66,67 (Supplementary Table 5a).

Three of the 95 genes identified were mapped by two of the prioritisation analyses (AC073133.1, MAN2B2, and SEMA6D; Supplementary Table 5a). AC073133.1 showed significant results for eQTLs for brain tissue with one variant (rs6969023) and for chromatin interaction in lung fibroblasts mediated by three variants (rs116530211,rs76374118,rs79338905; Supplementary Table 5a). MAN2B2 was identified by variant rs73207830 as being an eQTL in blood, and variant rs116755844 indicated chromatin interaction in the Promoter anchored Hi-C loops data from PsychENCODE65 (Supplementary Table 5a). SEMA6D showed evidence of both pathogenicity based on a high CADD score and chromatin interaction in lung fibroblast cells (Supplementary Table 5a).

For SC, only one variant had a CADD score higher than or equal to 15 but it was annotated as intergenic, thus not supporting any specific gene. The combination of the eQTL and the chromatin interaction mapping defined a total of 30 genes associated with 18 distinct variants (Supplementary Table 5b). The eQTL mapping identified two genes, CES1 and LPCAT2. While LPCAT2 was highlighted by only one dataset in blood (eQTLGen64), CES1 was retrieved by six datasets (BIOSQTL68, DICE69, eQLTCatalogue70, eQTLGen64, GTExv871, PsychENCODE65) including several blood cell types (B cells, monocytes, and T cells), and lung and brain tissues (Supplementary Table 5b). Both genes showed significant chromatin interaction values discovered in IMR90, a lung fibroblast cell line66 (Supplementary Table 5b). The remaining 28 genes showed SNP-mediated chromatin interaction both in the IMR90 cell line66 and in the Promoter anchored Hi-C loops data from PsychENCODE65 (Supplementary Table 5b).

Pathway analysis

We performed a pathway analysis to investigate biological interactions between the prioritised genes using the web-based tool Metascape developed for overrepresentation analysis of genes in biological pathways and protein–protein interaction55. We decided to focus only on pathways enriched with genes implicated by different loci, and so we performed this analysis only on the genes prioritised for SI. Fifty-five out of the ninety-five genes had an Entrez Gene ID and were analysed by Metascape resulting in two enriched pathways from Gene Ontology (GO) Resource. ‘Metanephros development’, the process to form the definitive kidney (GO:0,001,656), was enriched for FBN1, SHH and WFS1 genes (Log(P-value): − 3.50; Supplementary Table 6); the ‘developmental growth involved in morphogenesis’ (GO:0,060,560), a large GeneOntology category including several classes of morphogenesis activities was enriched for PDPN, SALL1, SEMA6D and SHH genes (Log(P-value): − 2.25; Supplementary Table 6). The protein–protein interaction network analysis identified two interactions: CYP4F3 with CYP4F8, and FBN1 with WFS1.

PheWAS analysis

We selected variants in the locus on chr 15 for a PheWAS analysis, as this was the only locus to replicate and it harboured SEMA6D, which was previously identified by other studies on smoking behaviour traits (see Discussion). We limited the PheWASs to variants supported by at least one of the four criteria of our gene prioritisation analysis obtaining a total of 4 variants: rs11634974, rs11636198, rs12905212, and rs7273389. The number of tested phenotypes for European individuals (ukb-d and ukb-d) differed among variants: from 2,443 (rs7273389), to 3,338 (rs11634974), to 3,342 (rs11636198 and rs12905212). For PheWASs in African ancestry individuals, all variants were tested for 1,152 distinct phenotypes.

We found Bonferroni-corrected significant results for fifteen traits only in European individuals: rs11634974, rs11636198 and rs12905212 showed association with the same 6 traits, including ‘Current tobacco smoking’ which had the same direction of effect as in this study, and ‘Qualifications: College or University degree’ with opposite direction of effect (Supplementary Table 7). The fourth variant, rs7273389, showed nine significant associations, seven of which were with body fat measures (Supplementary Table 7).

Discussion

Smoking is a preventable risk factor for several diseases worldwide1 with 80% of smokers living in LMICs and a rising prevalence in Africa3. GWASs have shown that genetics plays a role in smoking behaviours16,17, but similarly to other traits, most studies have been performed in individuals of European ancestry, thus underestimating the role of genetic diversity for these traits globally18,19. Disentangling the genetics of smoking in sub-Saharan Africa is essential to shed light onto its biology in this region and globally, and to help elucidate its role as a risk factor for non-communicable diseases, either directly or through interaction72.

In this study we focussed on understanding the genetics of two smoking behaviour traits, smoking initiation and cessation, in 10,558 men of African ancestry living in five countries in the African continent and the UK, including participants from three cohorts: AWI-Gen22, divided into three geographical areas (East, South and West), UGR23, and UKB-AFR24. After a two-step meta-analysis, we identified 7 loci associated with SI and one with SC, all in tier2 (variants with a meta-analysis P-value < 5 × 10–6 and P-value < 0.05 in each cohort). We selected variants for in silico functional follow up analyses based on their posterior inclusion probability of being causal, obtaining 136 variants for SI and 36 for SC. We compared the allele frequencies at these variants between the African (AFR) and European (EUR) superpopulations from 1000GP30 obtained via VEP52. All but one variant of five associated loci with SI (on chr 1, 4, 7, 10 and 16) were monomorphic or had a MAF < 2% in EUR, while they were common (MAF ranging 2–25%) in AFR (Supplementary Table 8). Despite being common in both AFR and EUR, most variants on chr 15 showed allele frequencies 2–5 times higher in AFR, and the only variant for chr 19 was common for both groups (Supplementary Table 8). Variants in the chr 16 locus associated with SC showed a general higher frequency in EUR (Supplementary Table 8). The variants identified by the few studies including AA individuals described in the introduction13,14,20,21 did not replicate in our study, with the caveat that they focused on smoking phenotypes different from our traits.

Our gene prioritisation strategy highlighted AC073133.1, MAN2B2, and SEMA6D for SI and CES1 and LPCAT2 for SC, as genes supported by two out of the four analyses included (CADD score, eQTLs, pQTLs and chromatin interaction). A detailed description of their function, and of the genes highlighted by the pathway and protein–protein interaction analyses is included in Supplementary Note 3. Only SEMA6D on chr 15 will be described in detail here as this locus shows strong evidence of replication, is involved in one of the two pathways identified, and includes eQTLs for a gene involved in a protein–protein interaction (FBN1). This gene is a member of the semaphorin family that encodes both secreted and membrane proteins involved in axon guiding, which may have a role in maintaining and remodelling neuronal connections (see URLs). It was already identified as associated with smoking initiation, cessation and amount by five studies17,21,45,46,47 including the largest study to date by the GSCAN17 consortium and the recent trans-ethnic GWAS meta-analysis of smoking trajectories in the MVP cohort21. Querying GWAS Catalog for SEMA6D (as of July 2021), we found reported associations for 63 traits (see URLs), including smoking and drinking behaviour phenotypes, depression and cognitive ability (see URLs). In agreement with our PheWAS, educational attainment and body mass index phenotypes were among the top five trait classes associated with SEMA6D (Supplementary Table 7).

We are aware this study has its limitations. The underrepresentation of individuals of African ancestry in biobank-scale cohorts affects several aspects of this work: from the limited sample sizes to the availability of additional datasets for larger meta-analyses, replication and follow up analyses. Not only does this influence the number of datasets available for genomics studies, but also the number of variants that can be tested for association, as shown by half of the tier2 loci being monomorphic or rare in EUR from 1000GP30 (Supplementary Table 8). The gender bias in smoking behaviours observed in our datasets led us to restrict the analyses to men only (Supplementary Table 1), impacting further on sample sizes and calling for specific attention to the cultural habits of tobacco consumption in some African populations. While it is true that smoking prevalence tends to be low among women in many African countries10,11, it is growing among girls6. The widespread use of chewing tobacco in some areas suggests that a new way of collecting data on tobacco use should be considered when developing studies that explore nicotine dependence at a population level.

This study adds support to a locus previously identified from large European and trans-ethnic studies, SEMA6D. Importantly it highlights the need for additional large African cohorts with tobacco exposure data to be developed and maintained and for different sub-phenotypes to be investigated in men and women. This is essential if we aim to overcome the limitations described above and be in a position to perform statistically powerful large-scale association studies across smoking behaviour phenotypes, as well as many other traits currently understudied in African populations.

Data availability

Complete summary statistics from the meta-analysis step2 for SI and SC are being deposited to NHGRI-EBI GWAS catalog [https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/] (Study accession numbers: SI, GCST90091238; SC, GCST90091239). Individual-level genetic and phenotypic data from the AWI-Gen (EGAD00010001996), Uganda Genome Resource (EGAS00001000545) and UK Biobank are available to approved researchers upon application or data access request. File handling and individual analyses were performed using a combination of bash and R scripts, available upon request from the authors.

References

WHO. The top 10 causes of death. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death (2020).

WHO. WHO report on cancer: Setting priorities, investing wisely and providing care for all. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-report-on-cancer-setting-priorities-investing-wisely-and-providing-care-for-all (2020).

WHO. Fact Sheets Tobacco. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco (2021).

WHO. FCTC. https://www.who.int/fctc/text_download/en/ (2003).

WHO. The MPOWER package. https://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/2008/en/ (2008).

WHO. Tobacco Control in Africa. https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/tobacco-control (2021).

J D, et al. The Tobacco Atlas. Atlanta: American Cancer Society and Vital Strategies (American Cancer Society Inc, Atlanta, 2018).

WHO. WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco smoking 2000–2025, third edition. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-global-report-on-trends-in-prevalence-of-tobacco-use-2000-2025-third-edition (2019).

Batini, C. et al. Smoking cessation on the African continent: Challenges and opportunities. Afr. J. Thorac. Crit. Care Med. 25, 46–48 (2019).

Sreeramareddy, C. T., Pradhan, P. M. & Sin, S. Prevalence, distribution, and social determinants of tobacco use in 30 sub-Saharan African countries. BMC Med. 12, 243 (2014).

Boua, P. R. et al. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of tobacco and alcohol use in four sub-Saharan African countries: A cross-sectional study of middle-aged adults. BMC Public Health 21, 1126 (2021).

Office for National Statistics. Adult smoking habits in the UK: 2019. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandlifeexpectancies/bulletins/adultsmokinghabitsingreatbritain/2019 (2019).

David, S. P. et al. Genome-wide meta-analyses of smoking behaviors in African Americans. Transl. Psychiatry 2, e119 (2012).

Chenoweth, M. J. et al. Genome-wide association study of a nicotine metabolism biomarker in African American smokers: Impact of chromosome 19 genetic influences. Addiction 113, 509–523 (2018).

Visscher, P. M. et al. 10 years of GWAS discovery: Biology, function, and translation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 101, 5–22 (2017).

Loukola, A. et al. A genome-wide association study of a biomarker of nicotine metabolism. PLoS Genet 11, e1005498 (2015).

Liu, M. et al. Association studies of up to 1.2 million individuals yield new insights into the genetic etiology of tobacco and alcohol use. Nat. Genet. 51, 237–244 (2019).

Gurdasani, D., Barroso, I., Zeggini, E. & Sandhu, M. S. Author correction: Genomics of disease risk in globally diverse populations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20, 562 (2019).

Martin, A. R. et al. Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities. Nat. Genet. 51, 584–591 (2019).

Hancock, D. B. et al. Genome-wide association study across European and African American ancestries identifies a SNP in DNMT3B contributing to nicotine dependence. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 1911–1919 (2018).

Xu, K. et al. Genome-wide association study of smoking trajectory and meta-analysis of smoking status in 842,000 individuals. Nat. Commun. 11, 5302 (2020).

Ramsay, M. et al. H3Africa AWI-Gen Collaborative Centre: A resource to study the interplay between genomic and environmental risk factors for cardiometabolic diseases in four sub-Saharan African countries. Glob. Health Epidemiol. Genom. 1, e20 (2016).

Gurdasani, D. et al. Uganda genome resource enables insights into population history and genomic discovery in Africa. Cell 179, 984-1002 e1036 (2019).

Bycroft, C. et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 562, 203–209 (2018).

Asiki, G. et al. The general population cohort in rural south-western Uganda: A platform for communicable and non-communicable disease studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 42, 129–141 (2013).

Shrine, N. et al. New genetic signals for lung function highlight pathways and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease associations across multiple ancestries. Nat. Genet. 51, 481–493 (2019).

McCarthy, S. et al. A reference panel of 64,976 haplotypes for genotype imputation. Nat. Genet. 48, 1279–1283 (2016).

Choudhury, A. B. J. et al. Meta-analysis of ~ 25,000 continental Africans provides insights into the genetic architecture of lipid traits. Manuscr. Under Rev. 5, 6668 (2020).

Gurdasani, D. et al. The African genome variation project shapes medical genetics in Africa. Nature 517, 327–332 (2015).

The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526, 68–74 (2015).

The UK10K Consortium. The UK10K project identifies rare variants in health and disease. Nature 526, 82–90 (2015).

Patterson, N., Price, A. L. & Reich, D. Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLOS Genet. 2, e190 (2006).

Zhou, X. & Stephens, M. Genome-wide efficient mixed-model analysis for association studies. Nat. Genet. 44, 821–824 (2012).

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007).

Turner, S. D. qqman: An R package for visualizing GWAS results using Q-Q and manhattan plots. J. Open Source Softw. 3, 731 (2018).

Bulik-Sullivan, B. K. et al. LD Score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 47, 291–295 (2015).

Han, B. & Eskin, E. Random-effects model aimed at discovering associations in meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88, 586–598 (2011).

Yang, J. et al. Conditional and joint multiple-SNP analysis of GWAS summary statistics identifies additional variants influencing complex traits. Nat. Genet. 44(369–375), S361-363 (2012).

Benner, C. et al. FINEMAP: Efficient variable selection using summary data from genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics 32, 1493–1501 (2016).

Thorgeirsson, T. E. et al. Sequence variants at CHRNB3-CHRNA6 and CYP2A6 affect smoking behavior. Nat. Genet. 42, 448–453 (2010).

Tobacco and Genetics Consortium. Genome-wide meta-analyses identify multiple loci associated with smoking behavior. Nat. Genet. 42, 441–447 (2010).

Gelernter, J. et al. Genome-wide association study of nicotine dependence in American populations: Identification of novel risk loci in both African-Americans and European-Americans. Biol. Psychiatry 77, 493–503 (2015).

Hancock, D. B. et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis reveals common splice site acceptor variant in CHRNA4 associated with nicotine dependence. Transl. Psychiatry 5, e651 (2015).

Wain, L. V. et al. Novel insights into the genetics of smoking behaviour, lung function, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (UK BiLEVE): A genetic association study in UK Biobank. Lancet Respir. Med. 3, 769–781 (2015).

Brazel, D. M. et al. Exome chip meta-analysis fine maps causal variants and elucidates the genetic architecture of rare coding variants in smoking and alcohol use. Biol. Psychiatry 85, 946–955 (2019).

Karlsson Linner, R. et al. Genome-wide association analyses of risk tolerance and risky behaviors in over 1 million individuals identify hundreds of loci and shared genetic influences. Nat. Genet. 51, 245–257 (2019).

Erzurumluoglu, A. M. et al. Meta-analysis of up to 622,409 individuals identifies 40 novel smoking behaviour associated genetic loci. Mol. Psychiatry 25, 2392–2409 (2019).

Chen, J. et al. Genome-wide meta-analyses of FTND and TTFC phenotypes. Nicotine Tob. Res. 22, 900–909 (2020).

Quach, B. C. et al. Expanding the genetic architecture of nicotine dependence and its shared genetics with multiple traits. Nat. Commun. 11, 5562 (2020).

Buniello, A. et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D1005–D1012 (2019).

Kircher, M. et al. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat. Genet. 46, 310–315 (2014).

McLaren, W. et al. The ensembl variant effect predictor. Genome Biol. 17, 122 (2016).

Watanabe, K., Taskesen, E., van Bochoven, A. & Posthuma, D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat. Commun. 8, 1826 (2017).

Folkersen L. Genomic evaluation of circulating proteins for drug target characterisation and precision medicine. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.03.023804v1 (2020).

Zhou, Y. et al. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 10, 1523 (2019).

Bader, G. D. & Hogue, C. W. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinform. 4, 2 (2003).

Carroll, R. J., Bastarache, L. & Denny, J. C. R PheWAS: Data analysis and plotting tools for phenome-wide association studies in the R environment. Bioinformatics 30, 2375–2376 (2014).

Elsworth B, et al. The MRC IEU OpenGWAS data infrastructure. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.10.244293v1 (2020).

Hemani, G. et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. Elife 7, e34408 (2018).

Mitchell R, Elsworth BL, Mitchell R, Raistrick CA, Paternoster L, Hemani G, Gaunt TR. MRC IEU UK Biobank GWAS pipeline version 2. https://doi.org/10.5523/bris.pnoat8cxo0u52p6ynfaekeigi (2019).

Pan-UKB team. https://pan.ukbb.broadinstitute.org (2020).

Liu, J. et al. The coexistence of copy number variations (CNVs) and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at a locus can result in distorted calculations of the significance in associating SNPs to disease. Hum. Genet. 137, 553–567 (2018).

Fromer, M. et al. Gene expression elucidates functional impact of polygenic risk for schizophrenia. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 1442–1453 (2016).

Võsa U. Unraveling the polygenic architecture of complex traits using blood eQTL metaanalysis. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/447367v1 (2018).

Wang, D. et al. Comprehensive functional genomic resource and integrative model for the human brain. Science 362, eaat8464 (2018).

Schmitt, A. D. et al. A compendium of chromatin contact maps reveals spatially active regions in the human genome. Cell Rep. 17, 2042–2059 (2016).

Giusti-Rodríguez P. Using three-dimensional regulatory chromatin interactions from adult and fetal cortex to interpret genetic results for psychiatric disorders and cognitive trait. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/https://doi.org/10.1101/406330v2 (2019).

Zhernakova, D. V. et al. Identification of context-dependent expression quantitative trait loci in whole blood. Nat. Genet. 49, 139–145 (2017).

Schmiedel, B. J. et al. Impact of genetic polymorphisms on human immune cell gene expression. Cell 175, 1701-1715 e1716 (2018).

Kerimov* N, et al. eQTL Catalogue: A compendium of uniformly processed human gene expression and splicing QTLs. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.29.924266v2 (2020).

GTEx Consortium. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science 369, 1318–1330 (2020).

Boua, P. R. et al. Novel and known gene-smoking interactions with cIMT identified as potential drivers for atherosclerosis risk in West-African populations of the Awi-Gen study. Front. Genet. 10, 1354 (2019).

Gaziano, J. M. et al. Million veteran program: A mega-biobank to study genetic influences on health and disease. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 70, 214–223 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank all volunteers from the AWI-Gen, UGR and UKB studies who have made this project possible. The AWI-Gen Collaborative Centre is funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), Office of the Director (OD), Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute Of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), the Office of AIDS Research (OAR) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), of the National Institutes of Health under award number U54HG006938 and its supplements, as part of the H3Africa Consortium. This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application 4892. This research is based on data from the Million Veteran Program73, Office of Research and Development, Veterans Health Administration, and was supported by the Veterans Administration (VA) Cooperative Studies Program (CSP) award #G002. The authors thank Million Veteran Program (MVP) staff, researchers, and volunteers, who have contributed to MVP, and especially participants who previously served their country in the military and now generously agreed to enrol in the study. (See https://www.research.va.gov/mvp/ for more details). This work was supported by the University of Leicester and Health Data Research UK, an initiative funded by UK Research and Innovation, Department of Health and Social Care (England) and the devolved administrations, and leading medical research charities. This study used the ALICE and SPECTRE High Performance Computing Facilities at the University of Leicester and the ZA-Wits-Core Cluster at University of the Witwatersrand. As this research was funded in whole, or in part, by the Wellcome Trust, for the purpose of open access, the author will apply a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission. C.B. was supported by an internal fellowship at the University of Leicester from the Wellcome Trust Institutional Strategic Support Fund (204801/Z/16/Z) and a UKRI Innovation Fellowship at Health Data Research UK (MR/S003762/1). M.D.T. is supported by a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award (WT202849/Z/16/Z). M.R. is a South African Research Chair in Genomics and Bioinformatics of African populations hosted by the University of the Witwatersrand, funded by the Department of Science and Technology, and administered by the National Research Foundation. C.S. acknowledges H3Africa Bioinformatics Network (H3ABioNet) Node, National Biotechnology Development Agency (NABDA), and the Center for Genomics Research and Innovation (CGRI) Abuja, Nigeria. S.F. is funded by the Wellcome International Intermediate fellowship (220740/Z/20/Z) at the MRC/UVRI and LSHTM. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.D.T., M.R., S.F., A.C. and C.B. designed the study. P.R.B., M.R., S.F. and A.C. collected the data. N.-N.P., C.S., N.S., J.-T.B., A.C. and C.B. prepared the data for analyses and performed initial quality controls. N.-N.P., P.R.B., C.S., N.S., K.C., J.-T.B. and C.B. performed data analyses. N.-N.P. and C.B. wrote the manuscripts and prepared figures and tables, with contributions from all authors. All authors critically evaluated and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. M.D. Tobin receives funding from GSK for collaborative research projects outside of the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Piga, NN., Boua, P.R., Soremekun, C. et al. Genetic insights into smoking behaviours in 10,558 men of African ancestry from continental Africa and the UK. Sci Rep 12, 18828 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22218-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22218-9

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.