Abstract

Introducing complementary feeding either early or later than 6 months is associated with future negative health outcomes. However, many women in Ethiopia do not follow WHO standard time to feed their children, which might be due to various demographic, economic, access, and availability of services. Thus, we aimed to identify factors attributing to the problems to assist future interventions. We used cross-sectional EMDHS 2019 for this analysis. We cleaned the data and 4061 women with under 2 years children were identified. We applied multilevel binary logistic regression in Stata v.15. Model comparison was based on log-likelihood ratio, deviance, and other criteria. We presented data using mean, percent, 95% CI, and adjusted odds ratio (AOR). The timely complementary feeding was 36.44% (34.93–37.92%). Factors like preceding birth intervals (AOR = 1.97 95% CI 1.62–1.39), primary education (AOR = 2.26 95% CI 1.40–3.62), secondary above education (AOR = 1.62 95% CI 1.10–2.38), and rich wealth index (AOR = 1.25 95% CI 1.03–1.52) were some of the associated factors. The magnitude of timely initiation of complementary feeding was diminutive. Authors suggest that interventions considering maternal education, empowering mothers economically, equity access to health services, and birth planning a good remedy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the 2019 Ethiopian Mini Demographic and Health Survey (EMDHS) report and World Health Organization (WHO) child feeding recommendation manual, complementary feeding is defined as feeding a child with solid and liquid foods in addition to breast milk1. Similarly, complementary feeding introduced at the age of 6th to 8th months is timely and outside this time range is untimely complementary feeding1,2,3. According to the WHO, exclusive breastfeeding is no-more enough to support child growth and development at and beyond the sixth month. Thus, children need breast milk plus additional (complementary) feeding to fill the lagging nutrients gap that is known for 45% of child deaths in low and middle-income countries3,4. Some studies defined timely complementary feeding as the food combined with breast milk within the 6–8 months after birth5,6,7. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) informs that families have been challenged by economic, political, market, social, or cultural barriers to feed their children affordably and safely in every corner of the world. Additionally, inappropriate complementary feeding affects 149 million children around the globe4,8. In addition, the magnitude of the problem is relatively higher in Sub-Saharan countries.

In South Asian countries, the untimely initiation of complementary feeding ranged from 17 to 76% in Bangladesh6. It was 61% in Pakistan5 followed by 43.6% in Nepal9. In Sub-Saharan countries, the average untimely initiation of complementary feeding is 31.7% in 201910. Similarly, a systematic review and meta-analysis in the Sub-Saharan region showed that 44.19% of mothers do not start complementary feeding as per WHO recommended time11. This is further explained by 62.5% of mothers initiating complementary feeding within 3-5 months in Nigeria12. In Ethiopia, a study in the Maichew district showed that around 40% of the mothers do not know the exact time of initiating complementary feeding13. And another study in Addis Ababa showed that 17% of mothers began complementary feeding earlier than 6 months 14. Another study in Dessie showed that 13.1% and 21.8% of mothers started giving complementary feeding earlier and later than recommended time respectively15. Additionally, in the Northwest Ethiopia, 47.2% of mothers also practiced untimely complementary feeding16, and it is 37% in the Northeast Ethiopia17. The new evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis in 2020 showed that 34.4% of the mother do not start complementary feeding at the recommended time18.

Previous studies already identified some of the predictors of untimely complementary feeding. In South Asia, lack of complementary feeding knowledge, low maternal education, socio-economic status, and cultural beliefs were the factors attributable to untimely complementary feeding5. Family iincome, lack of knowledge, and incorrect advice were some of the factors mentioned in another study19. A study conducted in Nigeria showed that orthodox maternity care, exclusive breastfeeding, and absence of the siblings were associated with the timely initiation of complementary feeding20. In Ethiopia, women’s employment, husband education, birth preparedness, growth monitoring, knowledge of time to introduce complementary feeding, and parental support were some of the factors affecting the time to initiate complementary feeding among mothers7,13,21,22,23. In another study, maternal education, complementary feeding counseling, and maternal knowledge also influenced the timing of initiating complementary feeding15. From this section, we understand that there is international, national, and regional shreds of evidence related to the topic area. However, the evidence is inconsistent throughout and inconclusive to trigger coordinated interventions. It indicates that further studies are necessary to find out critical factors to trigger intervention. In addition, there was no large-scale study addressing this topic since 2016. It is also important to assess if access, availability, socioeconomic, and socio-demographic changed over the last 5 years and if different decisions are necessary at country level to improvement the magnitude of problem.

Additionally, studies shows that a remarkable number of mothers do not adhere to the World Health Organization (WHO) complementary feeding recommendations; however, there is limited information on the larger population (country-level samples) for policy and decision-makers currently. Thus, this study had the aim of identifying factors enforcing mothers for untimely complementary feeding to provide the most recent representative information for further policy decisions from the recent country-level data using multilevel logistic regression that accounts for regional differences.

Methods

Study setting and data source

Ethiopia has conducted two EMDHS recently. In the 2019 EMDHS, the data collection was a community-based cross-sectional carried out from March 21, 2019, to June 28, 2019. All the nine regional states of the country (Afar, Tigray, Amhara, Oromia, Somali, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region (SNNPR), Benishangul Gumuz, Gambella, and Harari) and two city administrations (Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa) were included in the study.

We used secondary data (EMDHS) for this analysis. EMDHS used a stratified two-stage cluster sampling. Randomly, the Enumeration Areas (EA) have selected in the first stage and then households have selected in the second stage. In all selected households, height, weight measurements, and all nutritional data were collected from children aged 0–59 months. We included 4,061 women who are 15–49 year old from face-to-face interview questinnaire24. The details of the recorded data is now available from the measure program web address: (http://www.dhsprogram.com.). We extracted 4,061-weighted data from mother and children who live with their mothers for this analysis.

Study variables

Outcome variable

The outcome of this study was the timely initiation of complementary feeding. Complementary feeding is defined as the time when feeding other than breast milk is initiated between 6 and 8-months. It is untimely when it is commenced before 6 months or beyond 8 months. Below 6 and above 8 month initiation complementary feeding recoded as ‘0’ (no/not timely), and 6–8 month evidence of initiating complementary feeding recoded as ‘1’ (yes/timely).

Independent variables

The explanatory variables are the socio-demographic of the family, maternal services, and nutritional factors (Table 1).

Data processing and analysis

We used frequencies, weighted frequencies, mean, standard deviations, and percentages or proportions to describe the timely initiation of complementary feeding. We also calculated the mean Variance Inflation Factor (VIF = 1.23) is in the acceptable range. We also applied sampling weight to manage the representativeness of the survey and to account for sampling design when calculating standard errors.

We used a multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression model to analyze the data since EMDHS data has some structures. The data violates the independency of observations and the equal variance assumption of the traditional logistic regression model. In the current model, we fitted four models to estimate both fixed and random effects variables. We used the null model (intercept only model) to check the magnitude of intra-cluster variability. Second, we included all individual-level factors in the model (Model I). Additionally, Model II was fitted with community-level variables. And finally, we combined individual-level (fixed effect) and community-level (random effect) factors to form a mixed effect model (Model III) to identify factors associated with timely initiation of complementary feeding. Intra-cluster correlation is ICC \(= \frac{\partial 1}{{\partial 1 + \pi^{2/3)} }}\); where, \(\partial 1\) is the variance of the null model and \(\pi^{2/3}\) is the fixed number 3.29. Proportional Change in Variance is PCV \(= \frac{\partial 1 - \partial n}{{\partial 1}}\); where \(\partial 1\) is the null model variance and \(\partial n\) is thevariance of the neighborhood in the subsequent model. Median Odds Ratio is MOR \(= {\text{e}}^{{0.95\sqrt {\partial 1} }} { }\); where, \(\partial n\) is the variance of the null model. We used log-likelihood, deviance, AIC, and BIC to compare models and identified the best-fitted model using. We checked each variable for significance at p < 0.20 to include in models and used p < 0.05 for the final association indication. We cleaned the data as per the study criteria and analyzed it in STATA v. 15.0 after weighting.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance for the 2019 EMDHS was provided by the Ministry of Health ethics committee, the National Research Ethics Review Committee (NRERC), the Institutional Review Board of Inner City Fund (ICF) at DHS program internationally, and the Government of Ethiopia. The author obtained the 2019EMDHS data in different reading formats by online request at the DHS program. The authors also confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

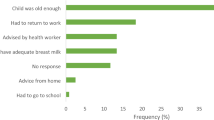

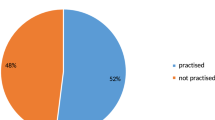

We analyzed 4061 children’s initiation of complementary feeding time and found 36.44% (34.93–37.92%), meaning more than 63% of families in Ethiopia initiate their children complementary feeding either earlier or later than the recommended time. Participants from agrarian regions accounted for 87.81% of this proportion. Nearly sixty percent (59.69%) of the mother were aged 25–34. Additionally, 50.10% of the mothers had two children under 5 years old, 61.98% of mothers were not learned, 48.85% of mothers were from poor wealth index families, 21.69% of preceding intervals were below 24 months, and 58.32% of mothers gave birth at their home (Table 2).

The analysis of factors associated with timely initiation of complementary feeding showed that the maternal age, maternal education, preceding birth interval, number of under five children, sex of the household leader, and the wealth index were significant. City administration City administration is the only significant random effect variable. Except for the sex of the household leader, all those variables were also significant under the final model (mixed effect model). We interpreted variables from the last model below. Accordingly, mothers with the age range of the 25–34 and the age ≥ 35 years had 40% and 53% reduced odds of untimely complementary feeding with AOR of 0.60 (0.49–0.74) and 0.47 (0.37–0.60) respectively compared to age 15–24 years. Conversely, mothers who reported preceding birth intervals greater than 36 months had 1.97 times more like to start complementary feeding timely with AOR of 1.97 (1.62–1.39) compared to 24 months. Mothers who had two and more under-five children during the survey had higher odds of starting complementary feeding timely with AOR of 3.63 (3.03–4.36) and 4.12 (3.25–5.21) respectively. Primary and secondary and above maternal education is positively associated with higher odds of timely initiation of complementary feeding with AOR of 2.26 (1.40–3.62) and 1.62 (1.10–2.38) respectively. Respondents from the rich family wealth index had high odds of reporting timely complementary feeding with AOR of 1.25 (1.03–1.52). At the community level, respondents from pastoralist regions had 33% reduced odds of initiating timely complementary feeding with AOR of 0.77 (0.61–0.98), and those from city administrations had higher odds of reporting timely complementary feeding with AOR of 1.47 (1.11–1.96) (Table 3).

Although the data is not highly affected by clusters, the results from Table 4 shown, the model fitting with balancing the existing hierarchies is adequate. The decreased ICC, AIC, BIC, deviance, and the increased log-likelihood ratio showed how the model improved over the multiple modeling. The 2% unaccounted ICC can be raid off by including additional random effect variables (Table 4).

Discussion

From our analysis, only 36.44% (95% CI 34.93–37.92%) of children started their complementary feeding within the WHO recommended time, which means nearly 64% of the children began complementary feeding either before 6 months or later than 8 months. The 64% untimely complementary feeding magnitude is less than 76% in Bangladesh6, but consistent with 61% in Pakistan5, and 62.5% in Nigeria12. It is greater than 43.6% in Nepal9, 44.19% in the Sub-Saharan region11, 47.2% in Northwest Ethiopia16, 37% in Northeast Ethiopia17; and 34.4% pooled prevalence in Ethiopia18. This means the finding is greater than the South Asian, regional, and country-level average untimely proportions. The higher untimely initiation of complementary feeding might show that mothers were more engaged in formula feeding as modified products are available and families might be exposed to a promoted product that might trigger usage at an inappropriate time. Some developing countries are worse than Ethiopia where untimely complementary feeding is higher and this might indicate the negative social, economic, and media (promotion) factors contribute higher in those countries. Additionally, 50.10% of the mothers had two children aged below 5 years. One study showed that most mothers are young and had ≥ 7 children25. This might be due to the shorter birth interval practiced by women in Ethiopia. It is not a secret that a 27.96% birth interval is around 35 months, which means mothers have the possibility of giving birth to another child before the fifth birthday of the preceding child. In other words, 61.98% of the mother had no education. This is supported by 62.8% of poor education in Nigeria20 and 54.0% in North Ethiopia but different from 30% in Northwest Ethiopia17. The consistency might indicate the poor achievement in maternal education both regionally and at country-level disquiet the situation. Maternal education is good in some small-scale studies that might show uneven distribution of maternal education in the country. In addition to this, 48.85% of mothers were from poor-wealth index families. This is also supported by many studies11,15,17,26. It might indicate that poor families are practicing more untimely complementary feeding. Poor families might be poorly educated (mothers) and income limited families where breast milk is not enough for their children and therefore start complementary feeding outside the recommended time. Overall, the economic status of people in the country is poor, so supporting mothers economically and promoting women’s education could be worth a lot.

During multilevel modeling, age of the mothers, maternal education, preceding birth interval, the number of children under 5 years old per woman, and wealth index—the fixed-effect factors, while pastoralists and city administrations—the random effect factors were significant. Mothers aged greater than 24 years were inversely associated with the timely initiation of complementary feeding in Ethiopia. Another study supported this idea23; however, mothers of age < 20 years were associated with the timely complementary feeding compared to the higher groups27. This might show that as age increase number of children increase and maternal breastfeeding capacity decrease and trigger untimely complementary feeding. Maternal education is an independent predictor of the timely initiation of complementary feeding. Many previous studies supported this concept in the country5,6,9,15,17,20. It means maternal education is an appealing intervention that undivided attention. As the preceding birth interval increase above 36 months, the probability of mothers sticking to the recommended time of initiating complementary feeding increases. Some studies support this in the country19,21. It might means child spacing special courtesy. However, it might also mean those mothers who were with good education, use family planning, and with good economic support only receives the service. Mothers with a rich wealth index had good timely initiation of complementary feeding, the impression also supported by other studies15,17. The consistency might be because rich mothers can buy baby formula and start complementary feeding untimely. It might also mean rich mothers are ignoring standard recommendations. Mothers from pastoralist regions do not practice timely complementary feeding while, mothers from city administrations did well. The regional difference regarding complementary feeding is also immense in another study28. The difference might be due to differences in equity distribution of health services, access, availability, and maternal education-related matters. Despite these finding of this study, some limitations need considerations. Disproportion of sampling, high missing in the data, secondary nature of the data, and others were some of the problems which authors approached through weighting, reducing sample by missing, and considering the time of data collection in the discussion were involved.

Conclusion

Depending on the finding of this study, the age of the mothers, maternal education, preceding birth interval, the number of children under 5 years old, wealth index, pastoralists, and city administrations need further commitment to have mothers practice timely complementary feeding. In addition to maternal education, wealth index and shorter birth intervals contributed to poor timing of complementary feeding. The availability of formula feeding for healthy children and the promotion of such products might be attracting many families to begin early complementary feeding. It might be difficult to tackle through the single best alternative. Therefore, governments, supplying (promoting) organizations, international and national organizations, and other stakeholders should work together for cumulative effect. Authors suggest critical attention is necessary to increase maternal education, women empowerment economically, access equity to service, and birth planning.

Data Availability

The survey dataset used in this analysis is the third party data from the demographic and health survey website (www.dhsprogram.com) and permission to access the data is granted only for registered DHS data user.

Abbreviations

- DHS:

-

Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey

- EMDHS:

-

Ethiopian Mini Demographic Health Survey

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- SNNPR:

-

South Nations Nationalities and Peoples Region

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- LL:

-

Log Likely-hood

- AIC:

-

Akaike Information Criterion

- BIC:

-

Baye’s Information Criterion

- UNICEF:

-

United Nation Children’s Fund

- ICC:

-

Intra-Cluster Correlation

References

Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019: Final Report. Rockville, Maryland, USA: EPHI and ICF. Vailable from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR363/FR363.pdf (2021).

Wang, L. et al. Factors associated with early introduction of complementary feeding and consumption of non-recommended foods among Dutch infants: The BeeBOFT study. BMC Public Health 19, 1–12 (2019).

World Health Organization. Complementary feeding.[internet]. 2021[cited 2022 April 15]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/complementary-feeding#tab=tab_1. (2021)

World Health Organization. Complementary Feeding: Family foods for breastfed children. Dep. Nutr. Heal. Dev. 1–56. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding (2000).

Manikam, L. et al. Systematic review of infant and young child complementary feeding practices in South Asian families: The Pakistan perspective. Public Health Nutr. 21, 655–668 (2018).

Manikam, L. et al. A systematic review of complementary feeding practices in South Asian infants and young children: The Bangladesh perspective. BMC Nutr. 3, 1–13 (2017).

Yeheyis, T., Berhanie, E., Yihun, M. & Workineh, Y. timely initiation of complementary feeding and associated factors among children aged 6 to 12 months in Addis Ababa Ethiopia, 2015. Epidemiol. Open Access 6, 4–12 (2016).

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Improving Young Children’s diets during the complementary feeding period. UNICEF Programming Guidance. New York: UNICEF (2020).

Acharya, D. et al. Correlates of the timely initiation of complementary feeding among children aged 6–23 months in Rupandehi district, Nepal. Children 5, 1–9 (2018).

Gebremedhin, S. Core and optional infant and young child feeding indicators in Sub-Saharan Africa: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 9, e023238 (2019).

Appiah, F. et al. Maternal and child factors associated with timely initiation of breastfeeding in sub-Saharan Africa. Int. Breastfeed. J. 16, 1–11 (2021).

Esan, D. T., Eniola, O., Iwari, A., Hussaini, A. & Adetunji, A. J. Complementary feeding pattern and its determinants among mothers in selected primary health centers in the urban metropolis of Ekiti State, Nigeria. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–9 (2022).

Reda, E. B., Teferra, A. S. & Gebregziabher, M. G. Time to initiate complementary feeding and associated factors among mothers with children aged 6–24 months in Tahtay Maichew district, northern Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 12, 1–8 (2019).

Mohammed, S., Getinet, T., Solomon, S. & Jones, A. D. Prevalence of initiation of complementary feeding at 6 months of age and associated factors among mothers of children aged 6 to 24 months in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Nutr. 4, 1–7 (2018).

Andualem, A., Edmealem, A., Tegegne, B., Tilahun, L. & Damtie, Y. Timely initiation of complementary feeding and associated factors among mothers of children aged 6–24 months in Dessie Referral Hospital, Northeast Ethiopia, 2019. J. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 1–7 (2020).

Biks, G. A., Tariku, A., Wassie, M. M. & Derso, T. Mother’s Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) knowledge improved timely initiation of complementary feeding of children aged 6–24 months in the rural population of northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 11, 1–7 (2018).

Sisay, W., Edris, M. & Tariku, A. Determinants of timely initiation of complementary feeding among mothers with children aged 6–23 months in Lalibela District, Northeast Ethiopia, 2015. BMC Public Health 16, 1–9 (2016).

Habtewold, T. D., Mohammed, S. H. & Tegegne, B. S. Breast and complementary feeding in Ethiopia: new national evidence from systematic review and meta-analyses of studies in the past 10 years: Reply. Eur. J. Nutr. 59, 841–842 (2020).

Manikam, L. et al. Complementary feeding practices for south asian young children living in high-income countries: A systematic review. Nutrients 10, 1–22 (2018).

Ogunlesi, T. A., Ayeni, V. A., Adekanmbi, A. F. & Fetuga, B. M. Determinants of timely initiation of complementary feeding among children aged 6–24 months in Sagamu, Nigeria. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 17, 785–790 (2014).

Alemayehu, Y., Ermeko, T., Hussen, A., Lette, A. & Abdulkadir, A. Timely initiation of complementary feeding practice among mothers and care givers of children age 6 To 24 Months in Goba town, Southeast Ethiopia. J Women’s Heal. Care 10, 1–7 (2021).

Shumey, A., Demissie, M. & Berhane, Y. Timely initiation of complementary feeding and associated factors among children aged 6 to 12 months in Northern Ethiopia: An institution-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1050 (2013).

Agedew, E. & Demissie, M. Early Initiation of complementary feeding and associated factors among 6 months to 2 years young children, in Kamba Woreda, South West Ethiopia: A community ?Based cross - sectional study. J. Nutr. Food Sci. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-9600.1000314 (2014).

Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF, (2016).

Kassa, T., Meshesha, B., Haji, Y. & Ebrahim, J. Appropriate complementary feeding practices and associated factors among mothers of children age 6–23 months in Southern Ethiopia, 2015. BMC Pediatr. 16, 1–10 (2016).

Semahegn, A., Tesfaye, G. & Bogale, A. Complementary feeding practice of mothers and associated factors in Hiwot Fana specialized hospital, eastern Ethiopia. Pan Afr. Med. J. 18, 1–11 (2014).

Gudeta, A. N., Andrén Aronsson, C., Balcha, T. T. & Agardh, D. Complementary feeding habits in children under the age of 2 years living in the city of Adama in the Oromia region in central Ethiopia: Traditional Ethiopian food study. Front. Nutr. 8, 1–7 (2021).

Shagaro, S. S., Mulugeta, B. T. & Kale, T. D. Complementary feeding practices and associated factors among mothers of children aged 6–23 months in Ethiopia: Secondary data analysis of Ethiopian mini demographic and health survey 2019. Arch. Public Heal. 79, 1–12 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Measure DHS, ICF International Rockville, Maryland, USA for allowing us to use the 2016 EDHS data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.G. has involved in conception, design, interpretation, writing methods, and analysis; while, S.S., & K.G. were involved in validation, drafting the manuscript, and reviewing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gilano, G., Sako, S. & Gilano, K. Determinants of timely initiation of complementary feeding among children aged 6–23 months in Ethiopia. Sci Rep 12, 19069 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-21992-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-21992-w

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.