Abstract

Obesity is a chief lifestyle disease globally and causes a significant increase in morbidities. Overweight/ obesity prevalence has been rising faster in India compared to the world average. Therefore, the study examined the association between overweight/ obesity and successful ageing among older population in India. We also explored the gender difference in risks posed by obesity on successful ageing and the different socio-economic correlates associated with successful ageing. This study utilized data from India’s first nationally representative longitudinal ageing survey (LASI-2017-18). The effective sample size for the present study was 31,464 older adults with a mean age of 69.2 years (SD: 7.53). Overweight/ obesity was defined as having a body mass index of 25 or above. The study carried out a bivariate analysis to observe the association between dependent and independent variables. Further, multivariable analysis was conducted to examine the associations after controlling for individual socio-demographic, lifestyle and household/community-related factors. The study included 47.5% men and 52.5% women. It was found that the prevalence of obesity/overweight was higher among older women compared to older men (23.2% vs 15.5%). Similarly, high-risk waist circumference (32.7% vs 7.9%) and high-risk waist-hip ratio (69.2% vs 66.5%) were more prevalent among older women than older men. The study found significant gender differences (men-women: 8.7%) in the prevalence rate of successful ageing (p < 0.001). The chances of successful ageing were significantly higher among older adults who were not obese/overweight [AOR: 1.31; CI 1.31–1.55], had no high-risk waist circumference [AOR: 1.41; CI 1.29–1.54], and those who had no high-risk waist-hip ratio [AOR: 1.16; CI 1.09–1.24] compared to their respective counterparts. Interaction results revealed that older women who were not obese/overweight had a lower likelihood of successful ageing compared to the older men who was not obese/overweight [AOR: 0.86; CI 0.80–0.93]. Similarly, older womens who had no high-risk waist circumference [AOR: 0.86; CI 0.80–0.96] and no high risk-hip ratio [AOR: 0.81; CI 0.73–0.89] were less likely to have successful ageing compared to their counterparts, respectively. Being overweight/ obese and having high-risk waist circumference and waist-hip ratio were found to be significant factors associated with less successful ageing among older adults, especially women in this study. The current findings highlight the importance of understanding the modifiable factors, including nutritional awareness and developing targeted strategies for promoting successful ageing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the continuous decrease in fertility and increase in life expectancy, population ageing is expected to rise across the globe and is expected to be one of the principal social changes of the twenty-first century1. Population above age 60 is projected to be 3.1 billion by 2100, which is a triple fold increase from that of 20172. While the relative share of the older population is higher in Western countries, the pace of population ageing and the absolute number of older adults are higher in Asian countries3. India has around 104 million population aged 60 and above, forming 8.6% of its population. The proportion is expected to rise to 20% of its population by 20504.

While there has been an increase in life expectancy over time, it was recognized that a rise in years lived may not necessarily be ‘ideal’ if it leads to more years of unhealthy life or add burden to younger generations5,6. The multidimensional concept of successful ageing was formulated in the context to describe the quality of ageing7. The concept has developed beyond a biomedical approach into a wider understanding of social and psychological adaptation processes in later life. While there is no exclusive definition for the concept of successful ageing, several studies empirically estimate successful ageing markers8. Most of the operational definitions of successful ageing use physiological constructs such as physical functioning, well-being constructs (like life satisfaction) and engagement in social and productive work9. While population ageing has been on the rise across almost all parts of the world, the experience with successful ageing has been mixed. Measures aimed at quantifying successful ageing have found that the rate of successful ageing to be as diverse as 10.9% in Korea10 to around 30% in France11. A review of 28 studies examined several definitions and metrics of successful ageing, and found a proportion of 35.8% of the population as successfully ageing, with smoking and diabetes as significant correlates in addition to socio-economic predictors12.

Another aspect of the demographic change has been the rise in non-communicable and lifestyle diseases. Obesity is a chief lifestyle disease globally and causes a significant increase in morbidities13. Obesity has been a major issue for the last three decades in advanced regions such as the USA and Europe14. Obesity and overweight prevalence has been rising faster in India compared to the world average. The prevalence of overweight increased from 8.4 to 15.5% among women between 1998 and 2015, and the prevalence of obesity increased from 2.2 to 5.1% over the same period15. Obesity has direct association with disability status16, cognitive abilities17, mental health18, chronic conditions19 and multi-morbidities20 in older population. In addition, to an increase in morbidities, obesity also increases the likelihood of mortality and decreases the quality of life years21. In this backdrop, a holistic understanding of health and wellbeing of older adults calls for an analysis of the multidimensional concept of successful ageing in the context of rising obesity.

However, the risks posed by obesity on successful ageing in India has been unexplored in literature. Evidence from other parts of the world suggests significant associations between obesity/ overweight status and successful ageing, with variations across age groups. Obesity was negatively associated with successful ageing indicators among the French older adults between age 65 and 7511. The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) suggested that an excess BMI decreased healthy and disease-free life expectancy among older adults between ages 50–7512. Evidence from China suggests that men with obesity/overweight were more successful agers, and women with underweight had a negative relationship with indicators of successful ageing. At the same time, obesity status was not significantly associated with successful ageing indicators for both men and women above age 75 years8.

In this paper, we examined the association between overweight/ obesity and successful ageing among the older population in India, using the data from the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI). We also explored the gender difference in risks posed by obesity on successful ageing and the different socio-economic correlates associated with ageing successfully.

Material and methods

Study design and participants

The data for this study come from India's first nationally representative longitudinal ageing survey (LASI-2017-18, wave 1), which looks at the health, economic, and social drivers and effects of population ageing in India22. Except for Sikkim, the sample comprised 72,250 older adults aged 45 and above, as well as their spouses, from all Indian states and union territories. To choose the final units of observation, the LASI uses a multistage stratified area probability cluster sampling methodology. The last unit of observation was households with at least one person aged 45 or older. This research offers empirical information on demographics, household economic status, chronic health problems, symptom-based health conditions, functional and mental health, biomarkers, health care usage, job and employment, and more. It was created to examine the impact of altering policies and behavioural outcomes in India, and it allows for cross-state and cross-national studies of ageing, health, economic status, and social behaviours. The LASI wave-1 report contains detailed information about the sampling frame. For this investigation, the effective sample size was 31,464 older individuals aged 60 years or older22.

Variable description

Outcome variable

Successful ageing differs from region to region, and the present paper defined successful ageing based on five criteria measured by utilizing self-reported survey questionnaires23,24. The five components were 1. Absence of chronic diseases 2. Freedom from disability 3. High cognitive ability 4. Free from depressive symptoms, and 5. Active social engagement in life. The older adults satisfying all the above conditions were considered as the successful ageing group8. The five components in detail are as follow:

-

1.

Absence of chronic diseases: Chronic diseases were assessed from the self-report question of “Have you been diagnosed with conditions listed below by a doctor?” The diseases were hypertension, chronic heart diseases, stroke, any chronic lung disease, diabetes, cancer or malignant tumour, any bone/joint disease, any neurological/psychiatric disease or high cholesterol25. Respondents were classified as having no chronic diseases if they reported to have none of the above-mentioned diseases.

-

2.

Freedom from disability: Activities of Daily Living (ADL) is a term used to refer to normal daily self-care activities (such as movement in bed, changing position from sitting to standing, feeding, bathing, dressing, grooming, personal hygiene etc.)22. The ability or inability to do ADLs is used to assess a person's functional state, particularly in the case of disabled people and older adults22. If respondents reported to be able to perform all of their daily activities independently, they were classed as having no disability22.

-

3.

High cognitive ability: Five broad domains were used to assess cognitive ability (memory, orientation, arithmetic function, executive function and object naming)22. Memory was measured using immediate word recall, delayed word recall; orientation was measured using time and place measure; arithmetic function was measured through backward counting, serial seven and computation method; executive function was measured through paper folding and pentagon drawing method, and object naming was lastly done to measure the cognitive function among older adults22. Using the domain wise measure, a composite score of 0–43 was calculated. The bottom tenth percentile is used as a marker for poor cognitive performance22. The cognitive ability of older persons who did not fall into the lowest tenth percentile was regarded to be high22.

-

4.

Free from depressive symptoms: The CIDI-SF (Short Form Composite International Diagnostic Interview) was used to calculate the likelihood of major depression in older persons with dysphoria with a score of 0-1022. This scale has been validated in field settings and is commonly used in population-based health studies to determine a probable mental diagnosis of major depression22. The cut-off of three was used for severe depression among older adults22. The older adults who scored less than three were considered free from depressive symptoms22.

-

5.

Active social engagement in life: Respondents were considered to be socially engaged if they participate in the following activities. Eat out of house (Restaurant/Hotel); Go to park/beach for relaxing/entertainment; Play cards or indoor games; Play outdoor games/sports/exercise/jog/yoga; Visit relatives /friends; Attend cultural performances /shows/Cinema; Attend religious functions /events such as bhajan/satsang/prayer; Attend political/community/organization group meetings; Read books/newspapers/magazines; Watch television/listen radio and use a computer for e-mail/net surfing etc.22. Older adults who reported any of the above activities at least once in a month were considered socially active.

Explanatory variables

Anthropometric measurement (key exposures)

Anthropometric measurements, such as height, weight, waist circumference, and hip circumference, were performed for all the LASI survey participants. The items "overweight" and "obesity" were classified as "no" and "yes". Obese/overweight was defined as having a body mass index of 25 or above26. No and yes were used to indicate high-risk waist circumference. Men and women who have High-risk waist circumferences were defined as those with circumferences of more than 102 cm and 88 cm, respectively27. No and yes were used to indicate the high-risk waist-hip ratio. Men and women with waist-hip ratios more than 0.90 cm and 0.85 cm, respectively, were classified as having a high-risk waist-hip ratio27.

Other covariates

Individual socio-demographic and lifestyle factors

After a thorough review of the literature, the factors that would be controlled in this study were chosen. Age was coded as young old (60–69 years), old-old (70–79 years), and oldest-old (80 + years). Education was categorized as no education/primary schooling not completed, primary completed, secondary completed, and higher and above. Marital status was grouped as currently married, widowed, and others (separated/never married/divorced). Working status was defined as working, retired, and not working. Living arrangement was categorized as living alone, living with a spouse, living with children and living with others. Tobacco and alcohol consumption was coded as no and yes. Physical activity status was coded as frequent (every day), rare (more than once a week, once a week, one to three times in a month), and never. The question through which physical activity was assessed was “How often do you take part in sports or vigorous activities, such as running or jogging, swimming, going to a health centre or gym, cycling, or digging with a spade or shovel, heavy lifting, chopping, farm work, fast bicycling, cycling with loads”?

Household/community-related factors

Using household consumption data, the monthly per-capita consumption expenditure (MPCE) quintile was determined. As a summary measure of consumption, the MPCE is computed and utilised and the details of the measurement are explained elsewhere22. Further, the variable was split into five quintiles, ranging from the lowest to the richest22. Religion was categorized as Hindu, Muslim, Christian, and Others. Caste was recoded as Scheduled Tribe, Scheduled Caste, Other Backward Class (OBC), and others. The Scheduled Castes are a group of people who are socially separated and financially/economically disadvantaged as a result of their low position in the Hindu caste system. The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are among India's most economically disadvantaged groups. The OBC refers to a large group of populations who have been classified as "educationally, economically, and socially backward." The OBCs are considered lower castes in the old caste hierarchy system, although the original caste system is not persistent in the country now. The “other” caste group refers to socioeconomically higher population and is regarded to have a better social rank28. The place of residence was coded as rural and urban. The region was grouped as North, Central, East, Northeast, West, and South.

Statistical analysis

The study carried out a bivariate analysis to observe the association between dependent and independent variables. Further, binary logistic regression analysis29 was performed to examine the associations after controlling for individual socio-demographic, lifestyle and household/community-related factors. The results were presented in the form of odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

The model is usually put into a more compact form as follows:

where \({\beta }_{0},\dots ,{\beta }_{M}\) are regression coefficient indicating the relative effect of a particular explanatory variable on the outcome. These coefficients change as per the context in the analysis in the study. The study further examined the possible interaction25,30 between obese/obesity, high-risk waist circumference, high-risk waist-hip ratio and gender in models 2, 3, and 4. Model 1 (full model) (controlled for all the individual and household characteristics) took into consideration the effect of background characteristics on older adults’ successful ageing rate. In model 2 (controlled for all the individual and household characteristics), the interaction of gender and obesity/overweight among older adults was observed. In model 3 (controlled for all the individual and household characteristics), the study observed the effect of gender and high-risk waist circumference among older adults. Finally, in model 4 (controlled for all the individual and household characteristics), the interaction of gender and high-risk waist-hip ratio among older adults was observed.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data is freely available in the public domain and survey agencies that conducted the field survey for the data collection have collected prior consent from the respondents. The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and all partner institutions extended the necessary guidance and ethical approval for conducting the LASI survey. Informed consent (verbal and written) was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Results

Socio-economic and demographic profile of older adults in India (Table 1)

Overall, 15,098 men (47.5%) and 16,366 women (52.5%) were included in the analysis. It was found that the prevalence of obesity/overweight was higher among older women compared to older men (15.5% vs 23.2%). Similarly, high-risk waist circumference (32.7% vs 7.9%) and high-risk waist-hip ratio (69.2% vs 66.5%) was more prevalent among older women than older men. A higher proportion of older adults belonged to the young-old cohort. The percentage of no education/primary not completed was higher among older women (81.4%) compared to older men counterparts (53.1%). Moreover, the proportion of working older men was higher than working older women (43.8% vs 19.0%). Older women were living more alone compared to older men (8.5% vs 2.5%). Tobacco (59.0% vs 22.4%) and alcohol consumption (27.6% vs 2.6%) was more prevalent among older men than older women counterparts. Older men (24.6%) did more frequent physical activity compared to older women (12%). A higher proportion of older adults were Hindu, belonged to other backward class caste, and lived in rural areas.

Percentage of older adults with successful ageing outcome by obesity-related measures and socioeconomic and demographic characteristics (Table 2)

The study found significant gender differences (men-women: 8.7%) in the prevalence of successful ageing outcomes (p < 0.001). Among the obesity-related factors, the highest gender difference in the successful ageing outcome was witnessed among older adults who were not obese/overweight (p < 0.001), followed by those who had no risk of high waist circumference (p < 0.001) and no risk of waist-hip ratio (p < 0.001). Moreover, among the individual factors, the highest gender difference in the successful ageing outcome was found among those who did the frequent physical activity (p < 0.001), followed by those who had a secondary level of education (p < 0.001) and older adults who lived alone (p < 0.001). Additionally, the maximum gender difference was observed among older adults who belonged to scheduled caste (p < 0.001), followed by Muslim older adults (p < 0.001) and those who belonged to Central India (p < 0.001).

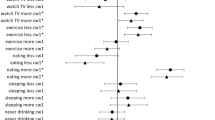

Estimates from logistic regression analysis for successful ageing among older adults

Table 3 presents four different models. Model 1 shows that the odds of successful ageing were significantly higher among older adults who were not obese/overweight [AOR: 1.31; CI 1.31–1.55], had no high-risk waist circumference [AOR: 1.41; CI 1.29–1.54], and those who had no high-risk waist-hip ratio [AOR: 1.16; CI 1.09–1.24] compared to their counterparts. Interaction results between obese/overweight and sex for successful ageing (Model 2,3 and 4) show that older women who were not obese/overweight had lower odds of successful ageing compared to older men who were not obese/overweight [AOR: 0.86; CI: 0.80–0.93]. Similarly, older women who had no high-risk waist circumference had lower odds of successful ageing compared to older men who had no high-risk waist circumference [AOR: 0.86; CI 0.80–0.96]. Additionally, with reference to older men who had no high risk-hip ratio, older women who had no high risk-hip ratio had lower odds of successful ageing [AOR: 0.81; CI 0.073–89].

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of nearly 31,500 older Indian men and women, we found more than 34% of older men and nearly 26% of older women in our study sample qualified as successful agers. The rate of successful ageing in our study is substantially higher compared to a recent study conducted in China using similar components, with around 19% of older men and 9.5% of older women being successful agers8. Possible reasons for higher rate of successful aging in India than China may be related to the use of different assessment tools for components of depression and cognition, eg., the Chinese study considered the Centre for Epidemiological Study Depression (CESD) scale for measuring depressive symptoms, whereas we used CIDI-SF scale that measures major depressive disorder. Another explanation is the lack of awareness and under-diagnosis of chronic diseases among older adults in India than in China. However, the rate is a little lower in comparison to an earlier review of 29 larger quantitative studies by Depp et al.12 that reported more than one-third of the community-dwelling older individuals (35.8%) on average qualified as successful agers. The review concluded that the nature of definitions and selected domains can lead to considerable variation in the proportion of successfully aging population.

The female disadvantage observed in successful ageing in this study may be explained by the gender paradox in health where, women with worse health tend to live longer than men31, and it is consistent with previous studies in other developing countries32,33. These differences seem to be attributed to men having improved cognition, increased physical function and social engagement than women in India34,35,36,37. In addition, it is documented that compared to men, women experience greater barriers to health service use, especially among socioeconomically poor people in India38. Furthermore, younger age and being married was associated with successful aging in comparison to old-old and widowed counterparts in this study, and the finding are consistent with previous studies39,40,41,42. The negative association between increasing age and achieving successful aging is expected due to the increase in functional, cognitive and biological decline with ageing. Besides, older adults who lived with a spouse or with children and spouse were significantly more likely to achieve successful ageing compared to those who lived with others in this study. This is in line with the argument that unlike Western model of successful aging, older individuals in India and other Asian countries focus more on familism and value the roles of spouse and children in successful aging43.

In the present study, we observed that obesity/ overweight, high-risk waist circumference and waste-hip ratio to be associated with a substantially reduced likelihood of successful ageing. This could be attributed to the increased lifestyle diseases associated with obesity and other adverse anthropometric measures32. These findings are also in parallel with studies that have documented nutrition and related anthropometric indices playing a pivotal and crucial role in maintaining older individuals’ physical capacity and optimal health44,45,46. Similarly, factors such as healthy nutrition, increased physical activity, improved stress management and greater resilience were found to be predictors of successful ageing32,47,48,49. Another study suggests that since most older individuals are more susceptible to foodborne illness, nutrition-based services should be provided to ensure successful ageing50. Further, physically active individuals in this study were more likely to have successful ageing than those who never did physical activity, which concurs with previous studies that suggest that physical activity reduces the progression of chronic disease and disabling conditions in older people and increase active life expectancy49,51,52. Similarly, compared to not working older adults, working older adults were more likely to have successful ageing and this finding supports the fact that older adults in the workforce maintain the same level of activity and social relationships as in earlier life stages and develop proactive behaviors for successful aging at work53,54.

To further determine whether high-risk status in obesity-related measures has different associations with successful ageing between men and women, we also tested for interaction between measures related to obesity and sex of the older individuals. In terms of women, compared with the older men who were normal weight, the obese women older population was significantly less likely to have successful ageing. This was similar with regards to high-risk waist circumference and waste-hip ratio. To illustrate further, the differences between older men and women in the rate of successful ageing with women being highly unsuccessful can be related to multiple factors. Firstly, the higher prevalence of obesity in women is a risk factor for arthritis and chronic conditions55,56,57. On the other hand, the higher obesity risk of women could be linked to their lower physical activity compared with men, particularly in societies with particular gender norms such as cultural inappropriateness of exercise by women and adverse environment with no or minimum accessible recreational areas/facilities58, which discourage physical activity in women throughout their life59,60.

The current study was subjected to several limitations. The observed gender disparities might have occurred due to misclassification in reporting symptoms because studies suggest that women are more likely to report depression and disability than men. Again, chronic diseases in our study are self-reported, leading to several biases and eventually influencing the rate of successful ageing; therefore, future research should look at the unsuccessful ageing caused by specific components rather than just looking at a composite index score. Further, importantly, the cross-sectional study cannot conclude causal inference between obesity-related measures and successful ageing; the follow-up in the future can, however, support the persuaded evidence. Nevertheless, the main strengths of this study include the conceptualization of successful ageing based on multiple outcomes, including validated measures of depression and cognitive functioning and objective measures of functioning. The large sample size and multiple covariates, which appear to be confounders, along with comprehensive information on socioeconomic characteristics of the ageing population, are further advantages.

Conclusion

Being overweight/ obese and having high-risk waist circumference and waist-hip ratio were found to be significant factors associated with less successful aging among older adults, especially women in this study. The current findings highlight the importance of understanding the modifiable factors, including nutritional awareness and developing targeted strategies for promoting successful ageing. The modifiable risk factors such as obesity and physical inactivity are obvious candidates for health promotion efforts in which health decision-makers can invest through supporting healthy eating and exercise among older people. Moreover, since Asian countries including India has had a relatively short history of tackling the issues related to ageing unlike developed countries, and for other reason, research into successful ageing has been lacking in many of these countries61, suggesting that further investigation is required with more follow-up survey information.

Data availability

The study utilizes a secondary source of data that is freely available in the public domain through a request from https://iipsindia.ac.in/sites/default/files/LASI_DataRequestForm_0.pdf.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ADL:

-

Activities of daily living

- CIDI-SF:

-

Short form composite international diagnostic interview

- MPCE:

-

Monthly per capita consumption expenditure

- OBC:

-

Other backward class

- SC:

-

Scheduled castes

- ST:

-

Scheduled tribes

References

Lutz, W., Sanderson, W. & Scherbov, S. The coming acceleration of population ageing. Nature 716, 1 (2008).

United Nations. World Population Prospects - Population Division - United Nations. World Population Prospects - 2015 Revision 2015; 1–5.

Balachandran A, de Beer J, James KS, et al. Comparison of Population Aging in Europe and Asia Using a Time-Consistent and Comparative Aging Measure. J Aging Health 2020; 089826431882418.

United Nations Population Division. The 2015 Revision of the UN’s World Population Projections. Popul. Dev. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00082.x (2015).

Robine, J. M., Saito, Y. & Jagger, C. The relationship between longevity and healthy life expectancy. Qual. Ageing 10, 5–14 (2009).

Balachandran, A. & James, K. S. A multi-dimensional measure of population ageing accounting for Quantum and Quality in life years: An application of selected countries in Europe and Asia. SSM Popul. Health 7, 100330 (2019).

Rowe, J. W. & Kahn, R. L. Successful aging. The Cerontologist 37, 433–440 (1997).

Luo, H. et al. Association between obesity status and successful aging among older people in China: Evidence from CHARLS. BMC Public Health 20, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08899-9 (2020).

Cosco, T. D. et al. Lay perspectives of successful ageing: A systematic review and meta-ethnography. BMJ Open 3, e002710 (2013).

Kim, H.-J., Min, J.-Y. & Min, K.-B. Successful aging and mortality risk: the Korean longitudinal study of aging (2006–2014). J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 20, 1013–1020 (2019).

Dahany, M.-M. et al. Factors associated with successful aging in persons aged 65 to 75 years. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 5, 365–370 (2014).

Depp, C. A. & Jeste, D. V. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: A comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 14, 6–20 (2006).

Janssen, F., Trias-Llimós, S., Kunst, A.E. The combined impact of smoking, obesity and alcohol on life-expectancy trends in Europe. Int. J. Epidemiol.

Hruby, A. & Hu, F. B. The epidemiology of obesity: A big picture. Pharmacoeconomics 33, 673–689 (2015).

Luhar, S. et al. Forecasting the prevalence of overweight and obesity in India to 2040. PLoS ONE 15, e0229438 (2020).

Polyzos, S. A. & Mantzoros, C. S. Obesity: Seize the day, fight the fat. Metab. Clin. Exp. 92, 1–5 (2019).

Prickett, C., Brennan, L. & Stolwyk, R. Examining the relationship between obesity and cognitive function: A systematic literature review. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 9, 93–113 (2015).

Luppino, F. S. et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67, 220–229 (2010).

Thow, A. M. et al. The effect of fiscal policy on diet, obesity and chronic disease: A systematic review. Bull. World Health Organ. 88, 609–614 (2010).

Agborsangaya, C. B. et al. Multimorbidity prevalence in the general population: The role of obesity in chronic disease clustering. BMC Public Health 13, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1161 (2013).

Calle, E. E., Teras, L. R. & Thun, M. J. Obesity and mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 2197–2199 (2005).

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), NPHCE, MoHFW, et al. Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) Wave 1. Mumbai, India, 2020.

Rahe, C. et al. Associations between poor sleep quality and different measures of obesity. Sleep Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2015.05.023 (2015).

Rowe, J. & Kahn, R. Successful aging and disease prevention. Adv. Ren. Replace Ther. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1073-4449(00)70008-2 (2000).

Srivastava, S. et al. Interaction of physical activity on the related measures association of obesity—with multimorbidity among older adults : a population-based cross-sectional study in India. BMJ Open https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050245 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Association between obesity-related anthropometric indices and multimorbidity among older adults in Shandong (A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, China, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036664.

Anusruti, A. et al. longitudinal associations of body mass index, waist circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio with biomarkers of oxidative stress in older adults: Results of a large cohort study. Obes. Facts https://doi.org/10.1159/000504711 (2020).

Srivastava, S., & Kumar, S. Does socio-economic inequality exist in micro-nutrients supplementation among children aged 6–59 months in India ? Evid. Natl. Family Health. 1–12 (2021).

Osborne, J., & King, J. E. Binary logistic regression. In: Best Practices in Quantitative Methods. SAGE Publications, Inc., 2011, pp. 358–384.

Chauhan, S. et al. Interaction of substance use with physical activity and its effect on depressive symptoms among adolescents. J. Subst. Use 1, 1–7 (2020).

Luy, M. & Minagawa, Y. Gender gaps-Life expectancy and proportion of life in poor health. Health Rep. 25, 12 (2014).

Shafiee, M. et al. Can healthy life style predict successful aging among Iranian older adults?. Med. J. Islam Repub. Iran 34, 1–7 (2020).

Arias-Merino, E. D. et al. Prevalence of successful aging in the elderly in western Mexico. Curr. Gerontol. Geriatr. Res. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/460249 (2012).

Jain, U. et al. How much of the female disadvantage in late-life cognition in India can be explained by education and gender inequality. Sci. Rep. 12, 5684 (2022).

Kumar, M., Srivastava, S. & Muhammad, T. Relationship between physical activity and cognitive functioning among older Indian adults. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–13 (2022).

Srivastava, S. et al. Multivariate decomposition analysis of sex differences in functional difficulty among older adults based on longitudinal ageing study in India, 2017–2018. BMJ Open 12, e054661 (2022).

Berkman, L. F., Sekher, T. V., & Capistrant, B., et al. Social networks, family, and care giving among older adults in India. In: Aging in Asia: Findings from new and emerging data initiatives. National academies Press (US) (2012).

Brinda, E. M. et al. Socio-economic inequalities in health and health service use among older adults in India : Results from the WHO Study on Global AGEing and adult health survey. Public Health 141, 32–41 (2016).

Subramaniam, M. et al. Successful ageing in Singapore: Prevalence and correlates from a national survey of older adults. Singapore Med. J. 60, 22–30 (2019).

Nakagawa, T., Cho, J. & Yeung, D. Y. Successful aging in East Asia: Comparison among China, Korea, and Japan. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 76, S17–S26 (2021).

Feng, Q., Son, J. & Zeng, Y. Prevalence and correlates of successful ageing: A comparative study between China and South Korea. Eur. J. Ageing 12, 83–94 (2015).

Thoma, M. V. et al. Associations and correlates of general versus specific successful ageing components. Eur. J. Ageing 18, 549–563 (2021).

Feng, Q. & Straughan, P. T. What does successful aging mean? Lay perception of successful aging among elderly Singaporeans. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 72, 204–213 (2017).

Bouchard, D. R. et al. Is fat mass distribution related to impaired mobility in older men and women? Nutrition as a determinant of successful aging: The Quebec longitudinal study. Exp. Aging Res. 37, 346–357 (2011).

Gaudreau, P. et al. Nutrition as a determinant of successful aging: Description of the Quebec longitudinal study NuAge and results from cross-sectional pilot studies. Rejuvenation Res. 10, 377–386 (2007).

Gopinath, B. et al. Association between Carbohydrate Nutrition and Successful Aging over 10 Years. J. Gerontol. Ser. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 71, 1335–1340 (2016).

Harmell, A. L., Jeste, D. & Depp, C. Strategies for successful aging: A research update. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 16, 1–11 (2014).

Pruchno, R. & Carr, D. Editorial: Successful aging 2.0: Resilience and beyond. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 72, 201–203 (2017).

Baker, J., Meisner, B. A., & Logan, A.J., et al. Physical activity and successful aging in Canadian older adults. 223–235 (2009).

Wellman, N. S. Prevention, prevention, prevention: Nutrition for successful aging. J. Am. Diet Assoc. 107, 741–743 (2007).

Chodzko-Zajko, W., Schwingel, A. & Park, C. H. Successful aging: The role of physical activity. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 3, 20–28 (2009).

Dogra, S. & Stathokostas, L. Sedentary behavior and physical activity are independent predictors of successful aging in middle-aged and older adults. J. Aging Res. 1, 1 (2012).

Kooij, D. T. Successful aging at work: The active role of employees. Work Aging Retire 1, 309–319 (2015).

Kooij, D. T. et al. Successful aging at work: A process model to guide future research and practice. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 13, 345–365 (2020).

Boateng, G. O. et al. Obesity and the burden of health risks among the elderly in Ghana: A population study. PLoS ONE 12, e0186947 (2017).

Varì, R. et al. Gender-related differences in lifestyle may affect health status. Ann. Ist Super Sanita 52, 158–166 (2016).

Whitson, H. E. et al. Chronic medical conditions and the sex-based disparity in disability: The cardiovascular health study. J. Gerontol. Ser. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 65A, 1325–1331 (2010).

Horne, M. & Tierney, S. What are the barriers and facilitators to exercise and physical activity uptake and adherence among South Asian older adults: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Prev. Med. 55, 276–284 (2012).

Asp, M. et al. Physical mobility, physical activity, and obesity among elderly: Findings from a large population-based Swedish survey. Public Health 147, 84–91 (2017).

Yadav, K. & Krishnan, A. Changing patterns of diet, physical activity and obesity among urban, rural and slum populations in north India. Obes Rev 9, 400–408 (2008).

Cheng, S. T. et al. Successful aging: Asian perspectives. Success Aging Asian Perspect. 1, 349 (2015).

Funding

The authors did not receive any funding to carry out this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work: S.S. and T.M.; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work: S.S. and P.K.; drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: T.M., P.K. and A.B.; final approval of the version to be published: T.M. and S.S.; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: S.S., T.M., P.K. and A.B.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Muhammad, T., Balachandran, A., Kumar, P. et al. Obesity-related measures and successful ageing among community-dwelling older adults in India: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 12, 17186 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-21523-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-21523-7

This article is cited by

-

Association of food insecurity with successful aging among older Indians: study based on LASI

European Journal of Nutrition (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.