Abstract

This study aimed to compare health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in people with and without plantar heel pain (PHP). This was a cross-sectional observational study that compared 50 adult participants with PHP to 25 participants without PHP who were matched for age, sex and body mass index (BMI). HRQoL measures included a generic measure, the Short Form 36 version 2 (SF-36v2), and foot-specific measures, including 100 mm visual analogue scales (VASs) for pain, the Foot Health Status Questionnaire (FHSQ), and the Foot Function Index-Revised (FFI-R). Comparisons in HRQoL between the two groups were conducted using linear regression, with additional adjustment for the comorbidity, osteoarthritis, which was found to be substantially different between the two groups. For generic HRQoL, participants with PHP scored worse in the SF-36v2 physical component summary score (p < 0.001, large effect size), but there was no difference in the mental component summary score (p = 0.690, very small effect size). Specifically, physical function (p < 0.001, very large effect size), role physical (p < 0.001, large effect size) and bodily pain (p < 0.001, large effect size) in the physical component section were worse in those with PHP. For foot-specific HRQoL, participants with PHP also scored worse in the VASs, the FHSQ and the FFI-R (p ≤ 0.005, huge effect sizes for all domains, except FHSQ footwear, which was large effect size, and FFR-R stiffness, activity limitation, and social issues, which were very large effect sizes). After accounting for age, sex, BMI and osteoarthritis, adults with PHP have poorer generic and foot-specific HRQoL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plantar heel pain (PHP), also referred to as plantar fasciitis, is a very common foot disorder1. Up to 10% of the general adult population are estimated to be affected by PHP2,3,4,5,6,7,8, but it is also prevalent among younger, athletic populations, such as long distance runners9,10,11 and military personnel12. In adults 50 years of age and older who have PHP, the pain is classified as disabling in 82% of those affected13. PHP has been found in one study to lead to poorer foot-specific health-related quality of life (HRQoL)14, and individuals who experience it have been reported to have increased levels of depression, anxiety and stress15,16,17. Further, PHP has been found to have a prolonged course in many people, with approximately 45% of patients still experiencing pain after 10 years18, which leads to a substantial use of health services19,20,21 and a large economic burden22.

While many factors have been found to be associated with PHP, the cause of this painful condition is still not fully understood, with studies finding inconsistent results for most of the proposed factors23,24,25,26,27. Nevertheless, a recent systematic review found that body mass index (BMI) was consistently associated with PHP, with meta-analysis finding that people with PHP have on average a BMI of 2.28 kg/m2 (95% CI 1.34 to 3.22) more than people without PHP28. However, increased BMI, overweight and obesity have also been associated with poorer general HRQoL29,30,31,32, and more specifically, foot-related HRQoL33. Therefore, there appears to be a link between obesity, PHP and HRQoL. This is important as not all studies that have investigated HRQoL in PHP have controlled for weight or BMI14,23,34. Accordingly, increased weight or BMI may have confounded the findings from some of the studies that have investigated the association of PHP with HRQoL. Therefore, BMI, as well as other important factors such as age and sex, should be accounted for when investigating this issue.

This study aimed to assess differences in HRQoL between those with and without PHP. To achieve this aim, the study compared a group of participants with PHP to a group of participants without PHP that were matched for age, sex and BMI.

Methods

Some of the methods outlined below have been previously reported in an earlier publication related to this study35.

Study design

This was a cross-sectional observational study and is reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Statement (STROBE)36.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the La Trobe University Human Ethics Committee—Application 14-001—Melbourne, Australia. As part of this approval, the study adhered to the updated Australian National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007)37. All participants provided written informed consent prior to recruitment into the study.

Participants

The participants were 75 community-dwelling adults of either sex from the State of Victoria, Australia. There were two groups of participants: (i) a case group of 50 participants with PHP, and (ii) a control group of 25 matched participants without PHP (i.e. a ratio of 2:1 of cases to controls). Participants in the control group were matched to the case group by age (± 5 years), sex and BMI (± 10%).

Eligibility criteria

Participants were eligible if they:

-

(i)

Were aged 18 years or over;

-

(ii)

Had PHP for at least 1 month (if recruited to the PHP group);

-

(iii)

Were able to speak basic English, so they could provide informed consent prior to participation, follow instructions during the project, and to answer questions related to the study accurately.

Participants were excluded from the study if they:

-

(i)

Had any conditions (e.g. pregnancy, pacemaker, metal fragments, etc.) that would have precluded them from having the medical imaging related to the over-arching study (the over-arching study was investigating differences in medical imaging findings in people with and without PHP);

-

(ii)

Had any self-reported inflammatory arthritis (e.g. seronegative arthropathy), endocrine/neurological condition (e.g. diabetic peripheral neuropathy, stroke, etc.) or surgery (e.g. amputation, joint fusion, etc.) that had affected lower limb sensation or their ability to walk/run.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited via several methods including: advertising posters placed at relevant locations (e.g. La Trobe University, private and public health clinics, sporting and senior citizen clubs), the Health Sciences Clinic at La Trobe University, advertisements on relevant web-sites related to health, direct referral from health care practitioners, and via acquaintances of the investigators involved with the study and snowball sampling. Recruitment commenced on 12 January 2015 and was completed on 26 October 2018.

Sample size

The sample size was one of convenience and was largely dependent on the previously mentioned over-arching study (due to costs associated with the medical imaging). The recruitment ratio of 2 cases (participants with PHP) to 1 control (participant without PHP) was decided on to minimise the burden of recruiting age-, sex- and BMI-matched control participants.

Setting

The study was performed in one of three settings: (i) a research room in the Health Sciences Clinic at La Trobe University, (ii) a health science clinical tutorial room at La Trobe University, or (iii) in a room at a participant’s home with a hard floor (e.g. linoleum, concrete or wood).

Protocol

Data were collected by one of three of the authors (KBL, MRK, GVZ), all of whom were registered podiatrists with more than 10 years of experience at the time of data collection. Following informed consent, participants were examined in one session that took approximately one to one-and-a-half hours. Data were collected using a standardised assessment form.

Data collected

General participant information

Participants were asked for general participant information such as date of birth (which allowed calculation of age), sex, and general medical history (including co-morbidities such as diabetes, hypertension and osteoarthritis). In addition, if they were a participant with PHP, they were also asked for the duration of their symptoms.

Physical characteristics

Participants had their height (in metres) and weight (in kilograms) measured; subsequently, their BMI was calculated in kg/m2. The normal range for BMI as recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) is 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2, overweight is 25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2 and obese is ≥ 30.0 kg/m238. In addition, their waist and hip circumference was measured (in cm); subsequently their waist-hip ratio calculated. The WHO recommend that if the waist-hip ratio is ≥ 0.90 for men and ≥ 0.85 for women then this indicates abdominal obesity, which indicates a substantially increase risk of metabolic complications39.

Medications

Participants were asked to list any prescribed medications that they were currently using.

Level of education

Participants were asked to report their highest level of education that they had completed, which was categorised as: (i) no formal, (ii) less than primary school, (iii) primary school completed, (iv) high school (or equivalent) completed, (v) TAFE (technical college) completed, (vi) college/university completed, (vii) post graduate degree completed, (viii) don’t know, (ix) other (please state).

Physical activity

Physical activity was measured by the Stanford Activity Questionnaire, which was expressed as kilocalories expended per day40,41.

Generic and foot-specific HRQoL

In the absence of clear definitions of HRQoL42, we chose to include patient-reported health status measures that empirically evaluate the way health affects QoL43. We also included visual analogue scales in this study as they are commonly used in clinical practice and clinically-based research to determine pain levels at different timepoints and with different activities, although we recognise that some researchers might argue that the isolated measurement of pain is not technically a HRQoL measure on its own. The suite of measures we used are detailed below.

Generic HRQoL was measured with the Short Form-36™ Standard Health Survey, US Version 2 (SF-36), QualityMetric Incorporated and Medical Outcomes Trust44,45,46, and domains included physical function, role physical (role limitations due to physical health problems), bodily pain, general health, which made up the physical component, and vitality, social functioning, role emotional (role limitations due to emotional problems), mental health, which made up the mental component. Scores for the SF-36 range from 0 to 100 with lower scores indicating poorer health status and higher scores indicating better health status.

Foot -specific HRQoL was measured using the 100 mm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)47, Foot Health Status Questionnaire (FHSQ)48, and the Foot Function Index-Revised (FFI-R)49,50. Three 100 mm VAS assessments were taken that covered the typical course of PHP over the last week: first step pain (heel pain when first arising out of bed), average heel pain for today, and average heel pain for the last week. A score of 0 on a VAS represents no pain and a score of 100 represents the worst pain imaginable. For the FHSQ, domains include foot pain, foot function, footwear and general foot health. Scores for the FHSQ range from 0 to 100 with lower scores indicating poorer foot health status and higher scores indicating better foot health status for an individual. For the FFI-R, sub-scales include (foot) pain, (foot) stiffness, difficulty, activity limitation, and an overall FFI-R score can also be calculated. Scores for the FFI-R range from 0 to 100 with lower scores indicating better foot health status and higher scores indicating poorer foot health status (note: this scoring is opposite to the FHSQ and SF-36).

Data analysis

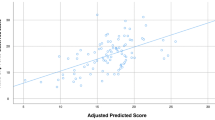

Data were analysed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 26.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). All continuous data were first explored for normality prior to inferential analysis. For categorical data, chi-square tests were used to test for differences between groups. For ordinal data, or non-normally distributed continuous data, medians and inter-quartile ranges (IQRs) were calculated and Mann–Whitney U tests were used to test for differences between groups. For continuous data, mean differences with 95% confidence intervals were calculated and unpaired t-tests were used to test for differences between groups. If any comorbidities were found to be substantially different between groups when evaluating HRQoL data, we conducted linear regression analyses to adjust for this covariate, so its influence on the findings was controlled for. The critical level of significance was set at α = 0.05. Beta coefficients were calculated for group membership (i.e. with or without PHP) and the covariate to provide an indication of the relative importance of these factors in explaining variance in HRQoL, and adjusted R square values were calculated for each model. To provide an estimation of the size of the differences in HRQoL between the groups, Cohen’s d effect size values were calculated for HRQoL measures by dividing the mean difference between the groups by the average of the standard deviations for both groups. Interpretations of the calculated effect sizes were taken from Sawilowsky51, which are 0.01 = very small, 0.2 = small, 0.5 = medium, 0.8 = large, 1.2 = very large, and 2.0 = huge.

Results

Participant characteristics

Seventy-five participants were recruited into the study. There were 50 participants with PHP (case group) and 25 participants without PHP (control group) that were matched for age, sex and BMI. There were no statistically significant differences in age, sex or BMI between the two groups (Table 1). The mean age was 49.1 years in the PHP group and 48.9 years in the control group, with a range for all participants of 23 to 75 years. Women comprised 58% of the PHP group and 56% of the control group. The mean BMI was 30.6 kg/m2 in the PHP group and 30.2 kg/m2 in the control group, which indicates participants were, on average, obese; although, the range of BMIs for all participants was from normal to very severely obese (range 20.1 to 47.7 kg/m2). In addition to BMI, the measure of abdominal obesity (via the waist-hip ratio) was also well matched between the PHP and the control groups two groups, as were education level, number of self-reported medications, and activity levels. Regarding symptoms in the PHP group, the median duration of symptoms was 6.5 months with a range of 1.0 to 80.0 months. Their mean first step pain on a 100 mm VAS was 53 mm, mean pain on the day of their assessment was 39 mm, and their mean pain in the last 7 days was 50 mm.

Groups were also compared for the prevalence of comorbidities that may have affected HRQoL. There were no statistically significant differences between groups (Table 2). However, the prevalence of the comorbidity osteoarthritis was substantially different between the groups (38% versus 16%), even though it was not statistically significant (p = 0.051), so we elected to adjust for this in the HRQoL comparisons.

Generic health-related quality of life

There were significant differences between the PHP and control groups in generic HRQoL; namely the SF-36—Table 3. Overall, the physical health component score was significantly lower in the PHP group, but there was no difference in the mental health component score. When individual domains were compared in the physical health component of the SF-36, the physical function, role physical and bodily pain domain scores were significantly lower in the PHP group, but there was no difference between the groups for the general health domain. When individual domains were compared in the mental health component, there were no significant differences between groups. Effect sizes ranged from large to very large for domains in the physical health component that were found to be statistically significant.

Foot-specific health-related quality of life

There were also significant differences between the PHP and control groups in foot-specific HRQoL; namely VAS pain (first step pain, average pain and average pain in the last 7 days), the FHSQ (all domains), and the FFI-R (all sub-scales)—Table 4. For the PHP group, all three timepoints for the VAS pain and all domains for the FHSQ and FFI-R (including the social issues domain) scored worse. Effect sizes ranged from very large to huge.

Discussion

Our study aimed to assess differences in HRQoL between adults with and without PHP while accounting for body mass. To achieve the aim of the study we compared a group of participants with PHP to a group of participants without PHP who were matched for BMI, as well as age and sex. Participants in the two groups were well matched on these three key matching criteria. Importantly, participants were well matched for BMI, a critical variable in the context of the aim of our study. In addition, the PHP and control groups also had similar abdominal obesity (via the waist-hip ratio), education levels, number of self-reported prescribed medications being taken, and activity levels. However, one comorbidity, osteoarthritis, was found to be substantially more prevalent in the PHP group, so we elected to adjust for this. With this approach, we believe that potential confounding was minimised, so we subsequently progressed to compare the two groups for generic and foot-specific HRQoL.

Participants with PHP were found to have worse generic HRQoL scores as assessed with the SF-36, however this was isolated to only domains in the role physical component. The overall physical component score, and the individual domains of physical function, role physical and bodily pain were found to be substantially worse in PHP participants with effect sizes interpreted as large to very large. We did not find any substantial differences in the mental component of the SF-36, which is in contrast to the findings of a recent systematic review17 that found moderate level evidence for associations between psychosocial variables and PHP. However, the studies in this systematic review used different methodologies, and most did not specifically account for BMI and other comorbidities like we did. Accordingly, previous research that has found such associations may have been confounded by comorbidities. The SF-36 scores observed in participants without PHP in our study are also similar to population norms from the 1995 National Health Survey conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics52. Therefore, although this survey was conducted more than 2 decades ago, it shows that our control group were largely representative of the population from the perspective of generic HRQoL, so participants with PHP in our study had substantially worse generic physical HRQoL than population norms. This provides a benchmark for the impact of PHP on individuals who experience it.

Participants with PHP were also found to have substantially worse foot-specific HRQoL, as assessed with the three foot-specific measures that we used: the VAS, the FHSQ, and the FFI-R. Furthermore, all domains/sub-scales of these outcome measures were found to be substantially worse in participants with PHP.

Firstly, three different VASs for pain were assessed that covered the typical course of PHP over the last week (first step pain, average pain today, and average pain in the last 7 days), all of which were found to be substantially worse in the PHP group with effect sizes interpreted as huge for all three. The issue of first step pain (heel pain when first arising out of bed) is characteristic of PHP1, as is daily pain that worsens with activity and more chronic pain that can last many years in some individuals18.

Secondly, all four domains of the FHSQ (pain, function, footwear and general foot health) were found to be substantially worse in the PHP group with effect sizes interpreted as huge, except for footwear, which was large. These findings are also greater than those found to be clinically meaningful53,54. A previous study by Irving et al.14 that adjusted for differences in BMI between a PHP and a control group also found individuals with PHP scored substantially worse in all four domains. The pain experienced with PHP is located on the plantar aspect of the heel and because standing and walking (and for some, running) are key activities for daily living, the findings from our study and the study conducted by Irving et al. are not surprising. There is one other study by Palomo-Lopez and co-workers34 that also assessed foot-specific HRQoL in adults with PHP, but their aim was to compare males and females with PHP, rather than adults with PHP in general to a control group without PHP. They found that females had worse foot-specific HRQoL in the FHSQ domains of foot function and footwear (but not pain and general foot health). The issue of footwear difficulties in people with PHP has not been extensively investigated using robust study designs, aside from a study by Sullivan et al.55, which our findings agree with. We believe, therefore, that future studies investigating footwear in PHP are warranted, including evaluations of the effectiveness of different types of footwear in appropriately powered randomised trials.

Thirdly, all domains or sub-scales of the FFI-R were found to be substantially worse in the PHP group with effect sizes interpreted as very large, except for pain and difficulty, which were huge. The FFI-R is similar to the FHSQ in that it empirically assesses foot health and its impact on QoL, although it does contain different domains or sub-scales, which are pain, stiffness, difficulty, activity limitation, social issues, and an overall FFI-R score can also be calculated. While overall, the FFI-R’s pain, stiffness, difficulty and activity limitation sub-scales are likely to measure similar issues to the FHSQ’s pain and function domains, albeit under four domains not two, the social issues sub-scale is unique to the FFI-R. The finding of a worse social issues score for the PHP group is in contrast to our findings for the generic HRQoL measure, the SF-36, discussed previously. These contrasting findings may simply be due to differences in foot specific versus generic HRQoL measures (i.e. foot specific is more sensitive to detect differences), but it may also be due to the sample size for our study not being large enough—as it was limited to the over-arching study—to detect clinically meaningful differences in generic HRQoL. Accordingly, we believe that further research is warranted on PHP’s effect on an individual’s psychosocial health (e.g. health concerns, mental health, ability to carry out daily activities and to engage socially)49.

In summary, adults with PHP have poorer generic and foot-specific HRQoL. The pain associated with PHP leads to affected individuals not only having poorer foot and broader physical function, but also poorer social functioning as detected by the FFI-R. The pain experienced under the heel, and the wider functional limitations that occur because of this pain, are hallmarks of PHP and there are many conservative treatments, such as stretching56, foot taping56, foot orthoses57, extracorporeal shockwave therapy58, and corticosteroid injection59 that are targeted at these symptoms and impairments. However, the broader psychosocial issues, including its impact on social functioning and roles an individual participates in are less well understood and deserve greater investigation17. While there is some early evidence that psychosocial factors, such as anxiety and depression, are factors in PHP15,16,60, the specific finding of poorer social functioning has only recently been reported in one qualitative study in which 18 participants underwent a semi-structured interview61. In addition, only one study has investigated PHP among assembly plant workers25, but this focused on risk factors, so further investigation of role limitations in work and other activities is warranted to better understand the broader economic and societal burdens of this condition.

There are several strengths to our study that should be highlighted. Our study matched a general sample of adult participants using a broad recruitment strategy with and without PHP for BMI. This is important as BMI has consistently been associated with PHP28,62, so unless controlled for, BMI may be a confounding factor in observational studies. We also adjusted for osteoarthritis, which after recruitment was found to be more prevalent in the PHP group. In addition, we utilised valid and reliable patient-reported outcome measures to assess HRQoL. Our findings, therefore, should be generalisable to the wider population of adults with PHP. Participants with PHP in our study were, on average, in their late 40s, although there was a substantial age range (mean 49 years, range of 23 to 75 years). The majority of participants (58%) with PHP were women, and they were on average obese (mean BMI was 30.6 kg/m2 with a range of 20.1 to 47.7 kg/m2). These values are consistent with other studies from different countries, including epidemiological investigations7,8,63, investigations of risk factors23,64,65,66, and randomised trials56,58. Regarding symptoms in the PHP group, the median duration of symptoms was 6.5 months in the PHP group with a range of 1 to 80 months. Their mean first step pain was 53 mm (measured on a 100 mm VAS), mean pain on the day of their assessment was 39 mm, and their mean pain in the last 7 days was 50 mm, which equates to pain levels that are moderate. Considered together, these findings indicate that the participants in this study are generalisable to the broader population of people with PHP, particularly middle-aged individuals, who make up the majority of cases7,63. Our study is also the first to include multiple measures of the impact of PHP on HRQoL, which makes it unique in that their findings support each other. The HRQoL measures we used included both generic and foot-specific measures, as well as multiple foot specific measures.

Our study has four limitations that need to be considered. Firstly, the sample size for the study was one of convenience as it was dictated by the limits of the over-arching study. Some of our findings, therefore, may be limited by sub‐optimal precision in the estimates of difference between groups. Secondly, we chose to recruit participants from the wider adult population with PHP, so our results are generalisable to these people, not to specific sub-populations with PHP (e.g. younger, active adults, such as long distance runners). Thirdly, our study did not utilise blinded investigators, however because the HRQoL measures were self-reported (i.e. patient-reported outcome measures), we do not believe that assessor bias was an issue. Finally, our study was cross-sectional, so we cannot make inferences about cause and effect.

Conclusion

After accounting for age, sex, body mass and osteoarthritis, adults with PHP have poorer generic and foot-specific HRQoL. While pain and functional impairment associated with PHP have already received considerable investigation, further research is needed to fully understand its impact on mental health, specifically its effects on the ability for an individual to function socially and on the roles that they would normally participate in, including work.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Buchbinder, R. Plantar fasciitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 2159–2166 (2004).

Thomas, M. J. et al. The population prevalence of foot and ankle pain in middle and old age: A systematic review. Pain 152, 2870–2880 (2011).

Hill, C. L., Gill, T. K., Menz, H. B. & Taylor, A. W. Prevalence and correlates of foot pain in a population-based study: The North West Adelaide health study. J. Foot Ankle Res. 1, 2 (2008).

Dunn, J. E. et al. Prevalence of foot and ankle conditions in a multiethnic community sample of older adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 159, 491–498 (2004).

Albers, I. S., Zwerver, J., Diercks, R. L., Dekker, J. H. & Van den Akker-Scheek, I. Incidence and prevalence of lower extremity tendinopathy in a Dutch general practice population: A cross sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 17, 16 (2016).

Nahin, R. L. Prevalence and pharmaceutical treatment of plantar fasciitis in United States adults. J. Pain 19, 885–896 (2018).

Rasenberg, N., Bierma-Zeinstra, S. M., Bindels, P. J., van der Lei, J. & van Middelkoop, M. Incidence, prevalence, and management of plantar heel pain: A retrospective cohort study in Dutch primary care. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 69, e801-808 (2019).

Riel, H., Lindstrøm, C. F., Rathleff, M. S., Jensen, M. B. & Olesen, J. L. Prevalence and incidence rate of lower-extremity tendinopathies in a Danish general practice: A registry-based study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 20, 239 (2019).

Warren, B. L. & Jones, C. J. Predicting plantar fasciitis in runners. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 19, 71–73 (1987).

Kibler, W. B., Goldberg, C. & Chandler, T. J. Functional biomechanical deficits in running athletes with plantar fasciitis. Am. J. Sports Med. 19, 66–71 (1991).

Clement, D. B., Taunton, J. E., Smart, G. W. & McNicol, K. L. A survey of overuse running injuries. Phys. Sportsmed. 9, 47–58 (1981).

Sadat-Ali, M. Plantar fasciitis/calcaneal spur among security forces personnel. Mil. Med. 163, 56–57 (1998).

Thomas, M. J. et al. Plantar heel pain in middle-aged and older adults: Population prevalence, associations with health status and lifestyle factors, and frequency of healthcare use. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 20, 337 (2019).

Irving, D. B., Cook, J. L., Young, M. A. & Menz, H. B. Impact of chronic plantar heel pain on health-related quality of life. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 98, 283–289 (2008).

Cotchett, M., Munteanu, S. E. & Landorf, K. B. Depression, anxiety, and stress in people with and without plantar heel pain. Foot Ankle Int. 37, 816–821 (2016).

Cotchett, M., Lennecke, A., Medica, V. G., Whittaker, G. A. & Bonanno, D. R. The association between pain catastrophising and kinesiophobia with pain and function in people with plantar heel pain. Foot (Edinburgh) 32, 8–14 (2017).

Drake, C., Mallows, A. & Littlewood, C. Psychosocial variables and presence, severity and prognosis of plantar heel pain: A systematic review of cross-sectional and prognostic associations. Musculoskelet. Care 16, 329–338 (2018).

Hansen, L., Krogh, T. P., Ellingsen, T., Bolvig, L. & Fredberg, U. Long-term prognosis of plantar fasciitis: A 5- to 15-year follow-up study of 174 patients with ultrasound examination. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 6, 2325967118757983 (2018).

Menz, H. B., Jordan, K. P., Roddy, E. & Croft, P. R. Characteristics of primary care consultations for musculoskeletal foot and ankle problems in the UK. Rheumatology (Oxford) 49, 1391–1398 (2010).

Riddle, D. L. & Schappert, S. M. Volume of ambulatory care visits and patterns of care for patients diagnosed with plantar fasciitis: A national study of doctors. Foot Ankle Int. 25, 303–310 (2004).

Whittaker, G. A., Menz, H. B., Landorf, K. B., Munteanu, S. E. & Harrison, C. Management of plantar heel pain in general practice in Australia. Musculoskelet. Care https://doi.org/10.1002/msc.1559 (2021).

Tong, K. B. & Furia, J. Economic burden of plantar fasciitis treatment in the United States. Am. J. Orthop. 39, 227–231 (2010).

Riddle, D. L., Pulisic, M., Pidcoe, P. & Johnson, R. E. Risk factors for plantar fasciitis: A matched case-control study. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 85-A, 872–877 (2003).

Irving, D. B., Cook, J. L. & Menz, H. B. Factors associated with chronic plantar heel pain: A systematic review. J. Sci. Med. Sport 9, 11–22 (2006).

Werner, R. A., Gell, N., Hartigton, A., Wiggerman, N. & Keyserling, W. M. Risk factors for plantar fasciitis among assembly plant workers. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2, 110–116 (2010).

Waclawski, E. R., Beach, J., Milne, A., Yacyshyn, E. & Dryden, D. M. Systematic review: Plantar fasciitis and prolonged weight bearing. Occup. Med. (Lond.) 65, 97–106 (2015).

Sullivan, J., Burns, J., Adams, R., Pappas, E. & Crosbie, J. Musculoskeletal and activity-related factors associated with plantar heel pain. Foot Ankle Int. 36, 37–45 (2015).

van Leeuwen, K. D. B., Rogers, J., Winzenberg, T. & van Middelkoop, M. Higher body mass index is associated with plantar fasciopathy/‘plantar fasciitis’: Systematic review and meta-analysis of various clinical and imaging risk factors. Br. J Sports Med. 50, 972–981 (2016).

Ul-Haq, Z., Mackay, D. F., Fenwick, E. & Pell, J. P. Meta-analysis of the association between body mass index and health-related quality of life among adults, assessed by the SF-36. Obesity 21, E322–E327 (2013).

Mickle, K. J. & Steele, J. R. Obese older adults suffer foot pain and foot-related functional limitation. Gait Posture 42, 442–447 (2015).

Hayes, M., Baxter, H., Müller-Nordhorn, J., Hohls, J. K. & Muckelbauer, R. The longitudinal association between weight change and health-related quality of life in adults and children: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 18, 1398–1411 (2017).

Sahle, B. W., Slewa-Younan, S., Melaku, Y. A., Ling, L. & Renzaho, A. M. N. A bi-directional association between weight change and health-related quality of life: Evidence from the 11-year follow-up of 9916 community-dwelling adults. Qual. Life Res. 29, 1697–1706 (2020).

Hendry, G. J., Fenocchi, L., Woodburn, J. & Steultjens, M. Foot pain and foot health in an educated population of adults: Results from the Glasgow Caledonian University Alumni Foot Health Survey. J. Foot Ankle Res. 11, 48 (2018).

Palomo-Lopez, P. et al. Impact of plantar fasciitis on the quality of life of male and female patients according to the Foot Health Status Questionnaire. J. Pain Res. 11, 875–880 (2018).

Landorf, K. B., Kaminski, M. R., Munteanu, S. E., Zammit, G. V. & Menz, H. B. Clinical measures of foot posture and ankle joint dorsiflexion do not differ in adults with and without plantar heel pain. Sci. Rep. 11, 6451 (2021).

von Elm, E. et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 61, 344–349 (2008).

National Health and Medical Research Council, the Australian Research Council and Universities Australia. National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (Updated 2018), https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/national-statement-ethical-conduct-human-research-2007-updated-2018 (Commonwealth of Australia, 2018).

World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (2021).

World Health Organization. Waist Circumference and Waist–Hip Ratio, Report of a WHO Expert Consultation, https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/obesity/WHO_report_waistcircumference_and_waisthip_ratio/en/ (2008).

Sallis, J. et al. Physical activity assessment methodology in the Five-City Project. Am. J. Epidemiol. 121, 91–106 (1985).

Richardson, M. T., Ainsworth, B. E., Jacobs, D. R. & Leon, A. S. Validation of the Stanford 7-day recall to assess habitual physical activity. Ann. Epidemiol. 11, 145–153 (2001).

Costa, D. S. J., Mercieca-Bebber, R., Rutherford, C., Tait, M.-A. & King, M. T. How is quality of life defined and assessed in published research? Qual. Life Res. 30, 2109–2121 (2021).

Karimi, M. & Brazier, J. Health, health-related quality of life, and quality of life: What is the difference? Pharmacoeconomics 34, 645–649 (2016).

Ware, J. E. & Sherbourne, C. D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 30, 473–483 (1992).

McHorney, C. A., Ware, J. E. Jr., Lu, J. F. & Sherbourne, C. D. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med. Care 32, 40–66 (1994).

McHorney, C. A., Ware, J. E. Jr. & Raczek, A. E. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med. Care 31, 247–263 (1993).

Price, D. D., McGrath, P. A., Rafii, A. & Buckingham, B. The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain 17, 45–56 (1983).

Bennett, P. J., Patterson, C., Wearing, S. & Baglioni, T. Development and validation of a questionnaire designed to measure foot-health status. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 88, 419–428 (1998).

Budiman-Mak, E., Conrad, K., Mazza, J. & Stuck, R. A review of the foot function index and the foot function index—Revised. J. Foot Ankle Res. 6, 5 (2013).

Budiman-Mak, E., Conrad, K., Stuck, R. & Matters, M. Theoretical model and Rasch analysis to develop a revised Foot Function Index. Foot Ankle Int. 27, 519–527 (2006).

Sawilowsky, S. S. New effect size rules of thumb. J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods 8, 597–599 (2009).

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 1995 National Health Survey: SF-36 Population Norms (Australia). Report No. ABS Catalogue No. 4399.0, 1–36 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, 1997).

Landorf, K. B. & Radford, J. A. Minimal important difference: Values for the Foot Health Status Questionnaire, Foot Function Index and Visual Analogue Scale. Foot 18, 15–19 (2008).

Landorf, K. B., Radford, J. A. & Hudson, S. Minimal Important Difference (MID) of two commonly used outcome measures for foot problems. J. Foot Ankle Res. 3, 7 (2010).

Sullivan, J., Pappas, E., Adams, R., Crosbie, J. & Burns, J. Determinants of footwear difficulties in people with plantar heel pain. J. Foot Ankle Res. 8, 40 (2015).

Landorf, K. B. Plantar heel pain and plantar fasciitis. BMJ Clin. Evid. 11, 1111 (2015).

Whittaker, G. A. et al. Foot orthoses for plantar heel pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 52, 322–328 (2018).

Babatunde, O. O. et al. Comparative effectiveness of treatment options for plantar heel pain: A systematic review with network meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 53, 182–194 (2019).

Whittaker, G. A. et al. Corticosteroid injection for plantar heel pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 20, 378 (2019).

Cotchett, M. P., Whittaker, G. & Erbas, B. Psychological variables associated with foot function and foot pain in patients with plantar heel pain. Clin. Rheumatol. 34, 957–964 (2015).

Cotchett, M. et al. Lived experience and attitudes of people with plantar heel pain: A qualitative exploration. J. Foot Ankle Res. 13, 12 (2020).

Butterworth, P. A., Landorf, K. B., Smith, S. E. & Menz, H. B. The association between body mass index and musculoskeletal foot disorders: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 13, 630–642 (2012).

Pollack, A. & Britt, H. Plantar fasciitis in Australian general practice. Aust. Fam. Phys. 44, 90–91 (2015).

Irving, D., Cook, J., Young, M. & Menz, H. Obesity and pronated foot type may increase the risk of chronic plantar heel pain: A matched case–control study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 8, 41 (2007).

McClinton, S., Collazo, C., Vincent, E. & Vardaxis, V. Impaired foot plantar flexor muscle performance in individuals with plantar heel pain and association with foot orthosis use. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 46, 681–688 (2016).

Rogers, J. et al. Chronic plantar heel pain is principally associated with waist girth (systemic) and pain (central) factors, not foot factors: A case-control study. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 51, 449–458 (2021).

Acknowledgements

HBM is currently a National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Research Fellow (ID: 1135995). Thank you to Lawrence Yap for assisting with processing some of the data included in this study. In addition, thank you to Glen Whittaker, Adam Fenton, John Osborne, Matthew Cotchett, Jade Tan, Maria Auhl, Stephanie Giramondo, Brad Dredge and Sarah Dallimore for their assistance in recruiting participants. The authors acknowledge the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nations as the Traditional Custodians of the land and its waterways on which they live and work. They recognise their unique contribution to the University they work at and to wider Australian society.

Funding

This project was funded from research grants provided by the Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation Research Focus Area and the School of Allied Health at La Trobe University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the study: K.B.L., H.B.M. and S.E.M. Acquisition of data: K.B.L., M.R.K., and G.V.Z. Processing of data: K.B.L. Analysis and interpretation of data: K.B.L., S.E.M. and H.B.M. Drafting the article: K.B.L., M.R.K., S.E.M., G.V.Z., and H.B.M. Final approval of the version submitted K.B.L., M.R.K., S.E.M., G.V.Z., and H.B.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Landorf, K.B., Kaminski, M.R., Munteanu, S.E. et al. Health-related quality of life is substantially worse in individuals with plantar heel pain. Sci Rep 12, 15652 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19588-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19588-5

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.