Abstract

Pharmaceutical care (PC) services reduce medication errors, improve the use of medicines, and optimize the cost of treatment. It can detect medication-related problems and improve patient medication adherence. However, PC services are not commonly provided in hospital pharmacies in Nepal. Therefore, the present study was done to determine the situation of PC in hospital pharmacies and explore the perception, practice, and barriers (and their determinants) encountered by hospital pharmacists while providing PC. A descriptive online cross-sectional study was conducted from 25th March to 25th October 2021 among pharmacists with a bachelor’s degree and above working in hospital pharmacies using non-probability quota sampling. The questionnaire in English addressed perception and practice regarding PC, and barriers encountered and were validated by experts and pre-tested among 23 pharmacists. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the data. Kendall’s correlation was used to explore the correlations among various perception and practice constructs. The scores were also compared among subgroups of respondents using the Mann–Whitney test for subgroups with two categories and Kruskal–Wallis test for greater than two categories. A total of 144 pharmacists participated in the study. Majority of the participants were male, between 22 and 31 years of age, and had work experience between 10 and 20 years. Over 50% had received no training in PC. The perception scores were higher among those with more work experience and the practice scores among those who had received PC training. Participants agreed that there were significant barriers to providing PC, including lack of support from other professionals, lack of demand from patients, absence of guidelines, inadequate training, lack of skills in communication, lack of compensation, problems with access to the patient medical record, lack of remuneration, and problems with accessing objective medicine information sources. A correlation was noted between certain perceptions and practice-related constructs. Hospital pharmacists who participated had a positive perception and practice providing PC. However, PC was not commonly practised in hospital pharmacies. Significant barriers were identified in providing PC. Further studies, especially in the eastern and western provinces, are required. Similar studies may be considered in community pharmacies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medicines are an important part of healthcare services provided to the users by a team of healthcare professionals, including doctors, pharmacists, nurses, and others. Medicine-related errors are common in Nepal while providing these services1,2,3. Medicine-related errors eventually affect the quality of medical care and worsen the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (increased morbidity and mortality rate), economy, and life expectancy4,5,6. Therefore, rational use of medicines and medication error prevention is a pressing need to reduce the health-related financial burden and preserve and promote HRQoL. This can be achieved to a larger extent by providing pharmaceutical care. Pharmaceutical Care (PC), as defined by Hepler and Strand (1990), “is the responsible provision of drug therapy for the purpose of achieving definite outcomes that improve a patient’s quality of life that involves the process through which a pharmacist co-operates with a patient and other professionals in designing, implementing and monitoring a therapeutic plan that will produce specific therapeutic outcomes for the patient”7. Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe (PCNE, 2013) defines PC as “the pharmacist’s contribution to care of individuals in order to optimize medicines use and improve health outcomes”8.

PC helps prevent disease complications through early identification, detection, and prevention of medicine-related problems, improves patient medication adherence, achieves therapeutic objectives, and makes the public aware of healthy lifestyle choices9. Major objectives of PC include identifying and mitigating pharmacotherapy-related problems by pharmacists in collaboration with other healthcare providers (e.g., clinicians, nurses)10. Many studies globally have reported improved health outcomes, reduced economic burden, and rational medication use through the provision of PC in patients with various disease conditions such as diabetes11, cardiovascular diseases12, and chronic respiratory diseases13. PC provision is important to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic as well14,15. Pharmacists have played a pivotal role in providing medicine-related services and PC in many countries15,16,17,18.

The pharmacy profession is still not well developed in Nepal, and pharmacists working in hospital settings are mainly engaged in dispensing, counselling about dispensed medicines, procurement, and managing pharmaceuticals and surgical items19. Although the clinical role of pharmacists is emerging in Nepal19,20, PC services are being provided only in very few hospitals where patients may be satisfied with the services21,22. Pharmacists provide clinical services, including drug information services, pharmacovigilance services, medication counselling, and patient education within the health facilities19,22,23,24,25.

Since many pharmacies in Nepal are still run by unqualified persons26,27, the status of PC in actual practice is questionable. To enhance the quality and standard of overall pharmaceutical service by pharmacists, the Nepal Pharmacy Council (NPC) developed the National Good Pharmacy guideline draft in 2005. In addition, the Department of Drug Administration (DDA), Nepal, developed a ‘Hospital Pharmacy Service Directive’ in 2015. Nevertheless, the implementation of these guidelines is lacking. The pharmacy undergraduate students of Nepal are deemed to understand the concept of PC and have a positive attitude towards its practice. However, various challenges include insufficient training and education on PC, constraints in obtaining patients’ clinical files with usual manual documentation practice, lack of drug information resources in pharmacies, and space problems in pharmacies located within the premises of private and government hospitals28.

Moreover, there is paucity of studies reporting perception, practice, and barriers regarding PC provision from the pharmacists’ point of view. So, the current study aimed to determine the situation of PC, and explore the perception, practice, and barriers (and their determinants) encountered by hospital pharmacists while providing PC in Nepal. This study would also provide a background for the concerned regulatory bodies to devise policies and arrangements to improve the PC services in Nepal.

Method

Study design and study period

A descriptive cross-sectional questionnaire-based survey was conducted from 25th March to 25th October 2021 in Nepal.

Study setting

The study was carried out among pharmacists working in hospital pharmacies in all seven provinces of Nepal, a lower middle-income country (LMIC) in South Asia. Pharmacists included in the study were those with a Bachelor’s degree in pharmacy (BPharm) or above. According to the pharmaceutical country profile, 2017, there are 0.8 registered pharmacists per 10,000 population in Nepal29.

Sample size

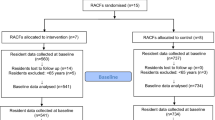

The sample size was calculated as 207 using the online survey size calculator considering a 95% confidence level and 5% confidence interval30. As the total population of pharmacists working in hospital pharmacies in Nepal was unknown, the target population was estimated using the International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) data of pharmacists working in hospital pharmacies in LMICs and NPC data on total registered pharmacists in Nepal. According to FIP and NPC, 9.3% of pharmacy practitioners work in hospital pharmacy settings in LMICs30, and 4829 pharmacists were registered in Nepal on 25th March 202031. These together provide a tentative population (449) of hospital pharmacists for sample size calculation. Adding 10% non-response, a total sample size of 228 (207 + 21) was calculated.

Sampling procedure

Non-probability quota sampling method was used, and the estimated sample was divided among all seven provinces based on the distribution of healthcare facilities to obtain the nationwide proportional representation32. Pharmacists working in hospital pharmacies were conveniently selected based on professional networks and interest in participating. Pharmacists with a bachelor’s degree in pharmacy or above and registered with the NPC were included. However, assistant pharmacists, pharmacy students, medical representatives, and industrial pharmacists were excluded. The estimated sample size is presented in Table 1.

Ethical approval and informed consent

The ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Board of Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC), Kathmandu, Nepal, on 16th May 2021 (Ref Number: 3136). Participants were informed about the study, and written informed consent was also obtained before collecting the responses. All methods applied were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data collection tools

Development of the structured questionnaire

The questionnaire was designed as a self-administered tool. The draft was initially prepared after an extensive literature review28,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48 and a thorough discussion among the co-authors. The authors who created the initial draft were hospital pharmacists, clinical pharmacists, and academicians in pharmacy. The tool was developed in English.

The data collection tool consisted of four parts: patient’s demographic and work-related information, perception-related questions, practice-related questions, and barrier-related questions. Initially, the socio-demographic and work-related section, perception-related section, practice-related section, and barrier-related section consisted of 11, 9, 11 and 27 questions, respectively. There were higher number of barrier-related questions since the researchers were interested in a more in-depth assessment of barriers. In addition, the researchers assumed that there were more barriers to PC in Nepal, which has prevented establishing and providing the same efficiently in hospital pharmacies.

Data collection

A web-based online approach was used to collect responses from the pharmacists at various hospital pharmacies. The online survey link for data collection was shared through pharmacy professional associations, email, online pharmacy networking portals/groups on social media, and WhatsApp groups. The first page of the survey contained the objective, nature, and benefit of the study which is followed by agree/disagree option at the end of the first page. Those who consented and agreed to participate in the study navigated to the questionnaire page on clicking the agree button.

Content validity

A panel of four experts was selected for the face and content validation of the research instrument. The panel consisted of university professors, lecturers and PhD scholars residing both in Nepal and abroad. They reviewed the questionnaire and provided their insights on the understanding of items and completeness of the questionnaire for measuring each theme and suggestions for revision. As per the experts’ suggestion, the arrangement, language, terminology, and question structure were revised, such as ‘lack of motivation’ was changed into ‘pharmacist lack motivation’, ‘Keeping patient’s clinical and medical information record’ into ‘Documenting patient’s clinical and medication information record’.

Face validity

The face validity of the questionnaire was studied among 23 pharmacists (10% of the total estimated sample) working in the province Bagmati. Participants were asked to complete the questionnaire and comment on its ease of understanding, readability, clarity, and suitability. The comments and suggestions received from the participants were discussed among the authors, and the tool was finalized. The data from these respondents were not included in the final analysis. After validation and reliability testing, patient’s demography and work-related questions, perception-related questions, practice-related questions, and barrier-related sections consisted of 14, 6, 11 and 26 questions, respectively (see S1 File).

Reliability analysis

Cronbach’s alpha value was calculated. It was found to be 0.429, 0.832 and 0.872 for perception-related questionnaires, practice-related questionnaires, and barrier-related questionnaires, respectively. As the alpha value for the perception-related questionnaire was low, three questions were removed following discussion among co-authors and only six were retained, giving an alpha value of 0.602.

Data analysis

Data from the predesigned form was entered in MS Excel and then analyzed with IBM statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) v 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) by applying descriptive statistics (i.e., mean, SD, frequency, and percentage) and inferential statistics (Kendall’s correlation) to explore the correlations among various perception and practice constructs of pharmaceutical care with qualifications, experience, site of work, working hours of the pharmacists, age of the respondents and number of daily prescriptions handled (i.e., daily workload). Values of Kendall’s tau were interpreted as less than ± 0.25 (very weak), ± 0.25 to ± 0.34 (weak), ± 0.35 to ± 0.39 (moderate), and ± 0.40 or larger (strong relationship). In addition, perception and practice scores were compared among subgroups using the Mann–Whitney U-test for two categories and the Kruskal–Wallis test for more than two categories. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant at a 95% confidence interval.

Results

Demographic characteristics of study participants

A total of 144 pharmacists responded. Maximum were male pharmacists (90, 62.5%), aged 22–31 years (119, 82.6%), with Bachelor’s in pharmacy (BPharm) degree (109, 75.7%), work experience of 10.1–20.0 years (133, 92.4%), and working at a private hospital pharmacy (65, 45.1%). More participants (143, 99.3%) worked on average for more than 35 h per week. Of the respondents, 76 (52.8%) participants had not received training in providing pharmaceutical care (Table 2).

Unfortunately, we could not attain the estimated sample size from six provinces except Province Bagmati. This was because of various reasons, such as inability to physically reach every hospital amid the COVID-19 pandemic, a comparatively lower proportion of graduate pharmacists in hospital pharmacies outside the capital city of Nepal, which is located in the province Bagmati, and the unwillingness of pharmacists to enrol in the study. The detail of the location of the pharmacists who participated is given in the supplementary file (see S2 File).

Pharmacy-related characteristics

Majority of the hospital pharmacies (101, 70.1%) operated more than 21 h daily, providing service to both outpatients and inpatients (125, 86.8%). An equal number of hospitals (41, 28.5%) had bed sizes of < 50 beds and ≥ 500 beds, and 95 (66%) pharmacies had 2–5 pharmacists in each shift (Table 3).

Pharmacists’ perception regarding providing pharmaceutical care

Of the respondents, 86 (59.7%) strongly agreed that patient’s medications should be reviewed to prevent medicine-related error, and 92 (63.9%) strongly agreed that pharmaceutical care improves patient’s treatment or health outcomes (Table 4).

Current practice of pharmaceutical care

Maximum pharmacists (90, 62.5%) counselled patients to prevent potential drug therapy-related problems, but maximum number of pharmacist (12, 8.3%) confessed that they never does monitoring of adverse effects of medicine. Only 34 pharmacist (23.6%) reported of monitoring adverse effects of medicine all the time (Table 5).

Detection of drug therapy related problems (DTRP) by the pharmacists

On an average, 134 pharmacists (93.1%) identified 1–100 errors related to drug dose, frequency, and duration; 135 (93.8%) pharmacists identified an equal range of errors related to drug name, dosage form and strength; 125 (86.8%) pharmacists identified equal errors on drug-drug interactions every month (Table 6).

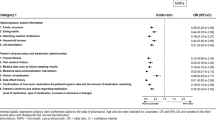

Barriers to providing pharmaceutical care

Maximum pharmacists (82, 56.9%) agreed that patients never asked for pharmaceutical care from them, and an equal number agreed that medicine practice and policy were oriented towards dispensing only. Similarly, 85 (59%) agreed that supportive practice guidelines were lacking nationally (Table 7).

Perception, practice and barrier scores among different subgroups of respondents

The perception scores were significantly different among subgroups of respondents with different work experiences (p value 0.048), and practice scores differed based on the presence or absence of training in PC (p value 0.017) (Table 8).

Correlation analysis of perception-related constructs and other variables

Kendall’s correlations were highly significant between constructs C1 and C2, C1 and C3, C2 and C3, C3 and C5, and C4 and C5, with a p value < 0.001 in each case, whereas there was no significant correlation of qualification with experience (p value 0.681), site of work (p value 0.386) and working hours per week (p value 0.153). Similarly, experience did not have a significant correlation with the site of work (p value 0.149) and working hours (p value 0.855) (Table 9).

Correlation analysis of practice-related various constructs and other variables

Kendall’s correlations were highly significant between constructs C1 and C2, C1 and C3, C1 and C4, C1 and C6, C1 and C7, C1 and C8, C1 and C9, C1 and C10, and many other constructs, with p value < 0.001 in each case (Table 10).

Discussion

Pharmacy practice in Nepal still has only a minimal patient focus. There have been initiatives to improve the situation of the pharmacy profession in the country, with more focus on patient-centeredness. Two initiatives to promote the pharmacy profession in Nepal include establishing a master’s in pharmacy program in pharmaceutical care at Kathmandu University in 2000 with alumni working in hospitals, academic and regulatory affairs, and drafting good pharmacy practice (GPP) guidelines in November 200549. Unfortunately, during the past two decades, the country has witnessed significant challenges such as an armed insurgency, political instability, and a major earthquake in 2015, all linked with poor employment, instability, and brain drain of qualified/skilled health workers49. These changes delayed the implementation of the draft GPP guidelines at the hospital level though there have been some initiatives from the government to improve the rational use of medicines in hospitals. The hospitals either outsource pharmacies to private parties on monthly rent or run as a minimalistic pharmacy setup with minimal space, infrastructure, and human resources, focusing only on procurement, storage, and selling of medicines and non-medical supplies22. There have been no studies assessing the patient care-related contribution of pharmacists in hospitals. The present study, probably the first of its kind in Nepal, reported a positive perception among hospital pharmacists and a reasonably good level of practice and many barriers encountered in offering PC services.

Perception regarding providing pharmaceutical care

Unfortunately, PC activities were absent in most hospitals in Nepal, with a few exceptions wherein self-motivated pharmacists offer these services individually or at their department level. Contrary to the conventional wisdom, the present study demonstrated a positive perception linked to a willingness to perform PC services and pharmacist’s work experience. The present study findings are similar to those reported by community pharmacists in China36, USA50, and Nigeria51. The perception part of the study questionnaire had six questions, and all responses had a median score of 4 or 5, suggesting a positive perception. However, it is essential to note that four respondents strongly disagreed with the statement ‘Patient’s medications should be reviewed to prevent medicine-related errors and promote appropriate use of medications, which shows pharmacists restricting themselves to traditional product-oriented roles and not offering patient care services. Pharmacists are expected to possess important skills such as communication, history taking, and physical assessment to offer PC services. In the present research, 7.6% of the respondents strongly disagreed that pharmacists in Nepal are professionally skilled in providing pharmaceutical care. Considering all the respondents have a minimum qualification of BPharm, the findings show the need for educational reforms and continuing professional education to train the pharmacists towards PC. Shrestha et al.19 recommended major changes in pharmacy education and focus on patient care education. In the present study, the pharmacists’ perception of PC was not influenced by demographic parameters other than the years of service. This finding suggests a general agreement among all pharmacists on the importance of PC services. The duration of service can naturally impact the pharmacist's attitude towards PC as more patient contact can help accept the professional roles.

Current practice of pharmaceutical care among hospital pharmacists

In line with the positive perception, the pharmacists also had a good practice related to PC services. However, it is noteworthy that this research was based on a self-reported survey, and the actual practice in the hospitals in terms of the quality of service was not verified by the researchers. The present study findings disagree with research from community pharmacies in Jordan52, Malaysia53, and hospitals in Pakistan54, wherein authors reported very limited or no PC services offered by community pharmacists. The location was different, being a hospital pharmacy in our study and a community pharmacy in others. These positive changes noted in the present study signify the recent changes in pharmacy practice in the country. The present study finding shows pharmacists' poor documentation of patients’ clinical and medication information, which can eventually be a barrier to practice. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) recommended that pharmacists be authorized to write inpatient medication records to document their assessments, conclusions, and recommendations on drug therapy10. However, this has not been implemented in Nepal. To offer patient care, the pharmacists should at least have access to medical records, a process that is largely missing in Nepal’s hospital pharmacies, although most hospitals have well-equipped computerized billing software. This gap requires intervention to improve pharmacists’ access to medical records and competence in interpreting patient data.

Further, the results showed a relatively low score for the statement ‘Reviewing patient’s prescription or medication profile to determine possible DTRPs. Studies from different countries have reported that pharmacists’ prescription reviews can help identify and mitigate DTRPs55,56,57. Identification and mitigation of DTRPs may be improved by providing more training to the pharmacists and improving access to drug information resources. Electronic databases can also help screen the prescriptions and detect DTRPs. While resolving DTRPs, one might require referring the patients to their physician, which most pharmacists did in reported studies. Though the pharmacists referred the patients to physicians, the extent of interprofessional collaboration (IPC) between pharmacists and physicians is not well studied in Nepal. Since lack of IPC can be a major barrier in providing PC, more research is needed.

PC practice is primarily influenced by training related to PC undergone by the pharmacists during their academic curriculum. At this point, it is worth mentioning that the curricula for pharmacists are inadequate to train the graduates in offering PC services. In addition, there are also challenges in offering experiential learning to the graduates, which lead to pharmacists being incompetent in patient care19. The present study findings also showed the existence of good counselling practices focusing on DTRPs prevention and non-pharmacological management of diseases, which is a welcome development. However, it was worth noting that pharmacists did not contribute much to adverse drug reactions (ADR) reporting and monitoring patients’ treatment progress to assure therapeutic goals. This can be improved only with proper education and training. Since underreporting of ADRs is considered a significant barrier in the current national pharmacovigilance program24,58, proper education and training of pharmacists can be valuable to improve the reporting rates and prevent their recurrence.

Perceived barriers to providing pharmaceutical care

The practice of PC can be primarily influenced by certain factors which can be modified to offer potential benefits. The common barriers to practicing pharmaceutical care reported in the literature are lack of pharmacist skills, lack of support from management, busy schedule, lack of incentives, etc.8,38,43,44,59. In the present study, the pharmacists reported multiple barriers (Table 8), like those reported in the literature8,38,43,44,59. These barriers encountered by the pharmacists were not influenced by their demography. There is a lack of support from other health professionals and poor coordination. The cooperation of other health professionals, especially physicians, is essential for promoting patient care and health outcomes.

On the contrary, a study from Kuwait reported physician agreement on pharmacists' contribution in managing ADRs, improving adherence, dosage adjustment, offering advice on drug interactions, and providing drug information (DI) to physicians60. The barrier noticed in the present study may be addressed by incorporating interprofessional education in the health professional curricula. Other barriers related to patients are poor literacy rates and lack of demand for PC. Health literacy is important for patient adherence, and in Nepal, there is a low literacy rate, especially in rural areas, which can certainly be a barrier. This can be overcome by offering customized patient-friendly educational materials by pharmacists.

Majority of hospital pharmacies in the country are outsourced by hospital management and are run as mere business entities. However, hospitals require their own hospital pharmacy according to hospital pharmacy guidelines61. This requires stringent regulatory intervention by the national drug regulatory body, i.e., DDA, to stop the practice of outsourcing pharmacies immediately. Pharmacists felt a lack of supportive PC practice guidelines in practising PC. More awareness needs to be created of the current GPP guidelines among pharmacists, and special training on GPP adherence may be conducted. Two studies conducted among community pharmacists reported poor compliance with GPP guidelines26,62. Though the setting is different, this may also have implications for pharmacy practice in hospital pharmacies.

Pharmacists perceived major barriers concerning their education, competency, and training. These barriers can be overcome only by improving pharmacy education and equipping future pharmacists with more competencies related to patient care. Since most pharmacies are more business-focused, one can expect a lack of human resources leading to a busy work schedule that naturally limits offering PC services. Pharmacists in Nepal also felt a lack of compensation as a barrier to PC services, similar to pharmacists from Nigeria63. The layout of the pharmacies is also crucial to examine patients in a private area and offer counselling which is mostly lacking in Nepal. The GPP guidelines of Nepal, however, emphasize layout requirements for pharmacies49.

Recommendations

The study findings recommend that more pharmacists are trained in patient care processes such as history taking, physical assessment, DTRPs identification and mitigation, and patient counselling. In addition, the pharmacy curricula must be critically examined and, if necessary, should be updated to offer competencies in PC. Furthermore, the pharmacies should ensure adequate human resources and pharmacy facilities to offer PC services. Outsourcing of pharmacies to private parties should be stopped, and hospitals should run their pharmacies. The GPP guideline, which is in the draft version, should be implemented without delay, and the implementation should be assessed periodically. Along with that, despite the hospital pharmacists finding an unfavorable situation to initiate PC, they should at least attempt to provide pharmaceutical care services such drug information, medication adherence monitoring and counseling on appropriate use, consulting or recommending patients to prescriber when they encounter any medication errors and drug interactions, and creating awareness on adverse drug reaction among patient and prescribers.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This is the first study to assess the pharmacists’ perception, practice, and barriers to PC services in Nepal. Furthermore, it is a nationwide study representing pharmacists in the entire country. Along with significant strengths, the study also has some limitations. First, the study used a convenient sampling method, and the authors could not achieve the requisite sample size. Secondly, the study only concentrated on pharmacists working in a hospital pharmacy setting. Therefore, it only represents the pharmaceutical care practices of hospital pharmacies. Thirdly, the study used an online Google survey link for data collection and shared the link through professional networks to reach only pharmacy professionals rather than sharing publicly on social media. Finally, this research was conducted during the peak period of COVID-19 pandemic prior to vaccine rollout, which might have limited pharmacists offering patient care services, thus influencing their responses. There is also a possibility of the Dunning–Kruger effect64 influencing the pharmacists’ responses to questions.

Conclusions

Hospital pharmacists who participated had a positive perception of providing pharmaceutical care. However, PC is not commonly practiced in hospital pharmacies. Significant barriers in providing PC were identified. Pharmacists believed that they might not have the requisite training to provide PC, access to patient records remained poor and commercial interests dominated hospital pharmacies. Adequate space, proper layout and adequate human resources are important to providing PC. Further studies, especially in the eastern and western provinces, are required. Similar studies may be considered in community pharmacies.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Shrestha, R. & Prajapati, S. Assessment of prescription pattern and prescription error in outpatient Department at Tertiary Care District Hospital, Central Nepal. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 12, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-019-0177-y (2019).

Kadir, A., Subish, P., Anil, K. & Ram, B. Pattern of potential medication errors in a tertiary care hospital in Nepal. Indian J. Pharm. Pract. 3, 25 (2010).

Karki, N., Kandel, K. & Prasad, P. Assessment of prescription errors in the internal medicine Department of a Tertiary Care Hospital in Nepal: A cross-sectional study. J. Lumbini Med. Coll. 9, 8. https://doi.org/10.22502/jlmc.v9i1.414 (2021).

Watanabe, J. H., McInnis, T. & Hirsch, J. D. Cost of prescription drug-related morbidity and mortality. Ann. Pharmacother. 52, 829–837. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060028018765159 (2018).

Elliott, R. et al. Prevalence and economic burden of medication errors in the NHS in England. Rapid evidence synthesis and economic analysis of the prevalence and burden of medication error in the UK (2018).

Organization, W. H. Medication Errors. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/252274 (2016).

Hepler, C. D. & Strand, L. M. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am. J. Hosp. Pharm. 47, 533–543 (1990).

Allemann, S. S. et al. Pharmaceutical care: The PCNE definition 2013. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 36, 544–555. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-014-9933-x (2014).

Al-Quteimat, O. M. & Amer, A. M. Evidence-based pharmaceutical care: The next chapter in pharmacy practice. Saudi Pharm. J. 24, 447–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2014.07.010 (2016).

ASOH-S Pharmacists. ASHP statement on pharmaceutical care. Am. J. Hosp. Pharm. 50, 1720–1723 (1993).

Nogueira, M., Otuyama, L. J., Rocha, P. A. & Pinto, V. B. Pharmaceutical care-based interventions in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 18, eRW4686. https://doi.org/10.31744/einstein_journal/2020RW4686 (2020).

Cazarim Mde, S., de Freitas, O., Penaforte, T. R., Achcar, A. & Pereira, L. R. Impact assessment of pharmaceutical care in the management of hypertension and coronary risk factors after discharge. PLoS One 11, e0155204. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155204 (2016).

Shanmugam, S. et al. Pharmaceutical care for asthma patients: A developing country’s experience. J. Res. Pharm. Pract. 1, 66–71. https://doi.org/10.4103/2279-042X.108373 (2012).

Song, Z., Hu, Y., Zheng, S., Yang, L. & Zhao, R. Hospital pharmacists’ pharmaceutical care for hospitalized patients with COVID-19: Recommendations and guidance from clinical experience. Res. Soc. Admin. Pharm. 17, 2027–2031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.03.027 (2021).

Zheng, S. Q. et al. Recommendations and guidance for providing pharmaceutical care services during COVID-19 pandemic: A China perspective. Res. Soc. Admin. Pharm. 17, 1819–1824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.03.012 (2021).

Hughes, C. M. et al. Provision of pharmaceutical care by community pharmacists: A comparison across Europe. Pharm. World Sci. 32, 472–487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-010-9393-x (2010).

Sakthong, P. & Sangthonganotai, T. A randomized controlled trial of the impact of pharmacist-led patient-centered pharmaceutical care on patients’ medicine therapy-related quality of life. Res. Soc. Admin. Pharm. 14, 332–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.05.001 (2018).

Westerlund, T. & Marklund, B. Assessment of the clinical and economic outcomes of pharmacy interventions in drug-related problems. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 34, 319–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.01017.x (2009).

Shrestha, S., Shakya, D. & Palaian, S. Clinical pharmacy education and practice in Nepal: A glimpse into present challenges and potential solutions. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 11. 541. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S257351 (2020).

Mikrani, R. et al. The impact of clinical pharmacy services in Nepal in the context of current health policy: A systematic review. J. Public Health 28, 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-019-01042-y (2020).

Upadhyay, D. K., Mohamed Ibrahim, M. I., Mishra, P. & Alurkar, V. M. A non-clinical randomised controlled trial to assess the impact of pharmaceutical care intervention on satisfaction level of newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus patients in a tertiary care teaching hospital in Nepal. BMC Health Serv. Res. 15, 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0715-5 (2015).

Shankar, P. R., Palaian, S., Thapa, H. S., Ansari, M. & Regmi, B. Hospital pharmacy services in teaching hospitals in Nepal: Challenges and the way forward. Arch. Med. Health Sci. 4, 212. https://doi.org/10.4103/2321-4848.196212 (2016).

Shrestha, S., Khatiwada, A. P., Gyawali, S., Shankar, P. R. & Palaian, S. Overview, challenges and future prospects of drug information services in Nepal: A reflective commentary. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 13, 287. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S238262 (2020).

Shrestha, S. et al. Impact of an educational intervention on pharmacovigilance knowledge and attitudes among health professionals in a Nepal cancer hospital. BMC Med. Educ. 20, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02084-7 (2020).

Sapkota, B., Bokati, P., Dangal, S., Aryal, P. & Shrestha, S. Initiation of the pharmacist-delivered antidiabetic medication therapy management services in a tertiary care hospital in Nepal. Medicine (Baltimore) 101, e29192. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000029192 (2022).

Shrestha, R. & Ghale, A. Study of good pharmacy practice in community pharmacy of three districts of Kathmandu valley, Nepal. Int. J. Sci. Rep. 4, 240. https://doi.org/10.18203/issn.2454-2156.IntJSciRep20184191 (2018).

Shrestha, S. et al. Bibliometric analysis of community pharmacy research activities in Nepal over a period of 1992–2018. J. Karnali Acad. Health Sci. 2, 243–249. https://doi.org/10.3126/jkahs.v2i3.26663 (2019).

Baral, S. R. et al. Undergraduate pharmacy students’ attitudes and perceived barriers toward provision of pharmaceutical care: A multi-institutional study in Nepal. Integrat. Pharm. Res. Pract. 8, 47. https://doi.org/10.2147/IPRP.S203240 (2019).

World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia. (2018). Nepal pharmaceutical profile 2017. World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274871.

Creative Research Systems. Sample Size Calculator [Internet]. Creative Research Systems. 2013. https://www.surveysystem.com/sscalc.htm.

Nepal Pharmacy Council. Pharmacist registered. https://www.nepalpharmacycouncil.org.np/members/search?search_input=&search_option=1&_token=tFdmtBlccWxod0Sr7O8FsZdqxeANNzmtr5AV1KYL.

Department of Health Services. Number of Health Facilities in Nepal-Health Emergency Operation Center [Internet]. https://heoc.mohp.gov.np/service/number-of-health-facilities-in-nepal/.

Ung, C. O. L. et al. Community pharmacists’ understanding, attitudes, practice and perceived barriers related to providing pharmaceutical care: A questionnaire-based survey in Macao. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 15, 847–854. https://doi.org/10.4314/tjpr.v15i4.26 (2016).

Ilyas, O. S. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice of community pharmacists towards pharmaceutical care in Kaduna State, Nigeria. Int. J. Pharm. Teach. Pract. 5, 1–5 (2014).

Ahmed, N. O. & AL-Wahibi, N. S. Knowledge attitude and practice towards pharmaceutical care in community pharmacy in Saudi Arabia. J. Adv. Med. Med. Res. 20, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.9734/BJMMR/2016/23920 (2016).

Fang, Y., Yang, S., Feng, B., Ni, Y. & Zhang, K. Pharmacists’ perception of pharmaceutical care in community pharmacy: A questionnaire survey in Northwest China. Health Soc. Care Community 19, 189–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00959.x (2011).

El Hajj, M. S., Hammad, A. S. & Afifi, H. M. Pharmacy students’ attitudes toward pharmaceutical care in Qatar. Ther. Clin. Risk Manage. 10, 121–129. https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S56982 (2014).

El Hajj, M. S., Al-Saeed, H. S. & Khaja, M. Qatar pharmacists’ understanding, attitudes, practice and perceived barriers related to providing pharmaceutical care. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 38, 330–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0246-0 (2016).

Alawi, S., Al-Abd, N., Rageh, A., Badulla, W. F. & Alshakka, M. Southern Yemeni pharmacy dispensers’ understanding, attitudes and perceived barriers related to pharmaceutical care. J. Drug Deliv. Therap. 10, 6–12. https://doi.org/10.22270/jddt.v10i4-s.4197 (2020).

Awaisu, A. et al. Self-reported attitudes and perceived preparedness to provide pharmaceutical care among final year pharmacy students in Qatar and Kuwait. Pharm. Educ. 18, 284–291 (2018).

Mishore, K. M., Mekuria, A. N., Tola, A. & Ayele, Y. Assessment of knowledge and attitude among pharmacists toward pharmaceutical care in eastern Ethiopia. BioMed Res. Int. 20, 20. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/7657625 (2020).

Inamdar, S. Z. et al. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice of community pharmacist towards the provision of pharmaceutical care: A community based study. Indian J. Pharm. Pract. 11, 25. https://doi.org/10.5530/ijopp.11.3.34 (2018).

Uema, S. A., Vega, E. M., Armando, P. D. & Fontana, D. Barriers to pharmaceutical care in Argentina. Pharm. World Sci. 30, 211–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-007-9167-2 (2008).

Ghazal, R., Hassan, N. A. G., Ghaleb, O., Ahdab, A. & Saliem, I. I. Barriers to the implementation of pharmaceutical care into the UAE community pharmacies. IOSR J. Pharm. 4, 68–74. https://doi.org/10.9790/3013-0405068074 (2014).

Suleiman, I. A. & Onaneye, O. Pharmaceutical care implementation: A survey of attitude, perception and practice of pharmacists in Ogun state, South-Western Nigeria. Int. J. Health Res. 4, 91–97 (2011).

AbuRuz, S., Al-Ghazawi, M. & Snyder, A. Pharmaceutical care in a community-based practice setting in Jordan: Where are we now with our attitudes and perceived barriers?. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 20, 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-7174.2011.00164.x (2012).

Xi, X., Huang, Y., Lu, Q., Ung, C. O. L. & Hu, H. Community pharmacists’ opinions and practice of pharmaceutical care at chain pharmacy and independent pharmacy in China. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 41, 478–487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-019-00802-w (2019).

Mehralian, G., Rangchian, M., Javadi, A. & Peiravian, F. Investigation on barriers to pharmaceutical care in community pharmacies: A structural equation model. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 36, 1087–1094. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-014-9998-6 (2014).

Council, N. P. National Good Pharmacy Practice Guidelines. https://pharmainfonepal.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/National-Good-Pharmacy-Practice-Guidelinese.pdf (2005).

Yancey, V., Yakimo, R., Perry, A. & McPherson, T. B. Perceptions of pharmaceutical care among pharmacists offering compounding services. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 48, 508–514. https://doi.org/10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07047 (2008).

Amibor, K. C. & Okonta, C. Attitude and practice of community pharmacists towards pharmaceutical care in Nigeria. J. Drug Deliv. Therap. 9, 164–171. https://doi.org/10.22270/jddt.v9i6-s.3786 (2019).

Mukattash, T. L. et al. Pharmaceutical care in community pharmacies in Jordan: A public survey. Pharm. Pract. (Granada) 16, 25. https://doi.org/10.18549/PharmPract.2018.02.1126 (2018).

Wong, Y. X., Khan, T. M., Wong, Z. J., Ab Rahman, A. F. & Jacob, S. A. Perception of community pharmacists in Malaysia about mental healthcare and barriers to providing pharmaceutical care services to patients with mental disorders. Community Ment. Health J. 56, 88–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00496-4 (2020).

Murtaza, G., Kousar, R., Azhar, S., Khan, S. A. & Mahmood, Q. What do the hospital pharmacists think about the quality of pharmaceutical care services in a Pakistani Province? A mixed methodology study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 756180. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/756180 (2015).

Eshiet, U. I., Okonta, J. M. & Ukwe, C. V. Evaluating the impact of pharmaceutical care services on the clinical outcomes of epilepsy: A randomised controlled trial. Iran. J. Med. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02599-y (2021).

Xin, C., Xia, Z., Jiang, C., Lin, M. & Li, G. Effect of pharmaceutical care on medication adherence of patients newly prescribed insulin therapy: A randomized controlled study. Patient Prefer Adherence 9, 797–802. https://doi.org/10.2147/ppa.S84411 (2015).

Al Tall, Y. R. et al. An assessment of HIV patient’s adherence to treatment and need for pharmaceutical care in Jordan. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 74, e13509. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13509 (2020).

Danekhu, K., Shrestha, S., Aryal, S. & Shankar, P. R. Health-care professionals’ knowledge and perception of adverse drug reaction reporting and pharmacovigilance in a tertiary care teaching hospital of Nepal. Hosp. Pharm. 56, 178–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018578719883796 (2021).

Ngorsuraches, S. & Li, S. C. Thai pharmacists’ understanding, attitudes, and perceived barriers related to providing pharmaceutical care. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 63, 2144–2150. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp060054 (2006).

Albassam, A., Almohammed, H., Alhujaili, M., Koshy, S. & Awad, A. Perspectives of primary care physicians and pharmacists on interprofessional collaboration in Kuwait: A quantitative study. PLoS One 15, e0236114. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236114 (2020).

Hospital pharmacy guideline 2072. Kathmandu (Nepal): Government of Nepal, Ministry of Health and Population. https://pharmainfonepal.com/hospital-pharmacy-service-guideline-2072.

Achary, A. & Khanal, D. Compliance on good pharmacy practice (GPP) guideline in community pharmacy of Western Nepal, Nepalgunj. J. Pharm. Pract. Educ. 3, 25. https://doi.org/10.36648/pharmacy-practice.3.2.25 (2020).

Okonta, J. M., Okonta, E. O. & Ofoegbu, T. C. Barriers to implementation of pharmaceutical care by pharmacists in Nsukka and Enugu metropolis of Enugu state. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 3, 295. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-0105.103823 (2012).

Pennycook, G., Ross, R. M., Koehler, D. J. & Fugelsang, J. A. Dunning–Kruger effects in reasoning: Theoretical implications of the failure to recognize incompetence. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 24, 1774–1784. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-017-1242-7 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Prof. Dr. Mohamed Izham Mohamed Ibrahim (College of Pharmacy, QU Health, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar), Dr. Mukhtar Ansari (Department of Clinical Pharmacy, College of Pharmacy, University of Hail, Saudi Arabia), Dr. Saval Khanal (Division of Health Sciences, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK), and Mr. Shakti Shrestha (School of Pharmacy, The University of Queensland, Australia) for providing their valuable comments and suggestions during the content validation process. The authors would like to thank all colleagues and seniors for helping reach out to and receive the response of the target population. Also, the authors would like to express our gratitude to all the hospital pharmacists for their valued participation in the project. Authors would like to acknowledge Ajman University for supporting the payment of the publication processing fee.

Disclosure of Statement

The part of this manuscript is accepted for eposter presentation in ACPE 2022 ISPE's 14th Asian Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology 21-23 October 2022 Tainan, Taiwan

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the study: R.S., S.P., B.S., S.S., P.R.S. Performed the study/data collection: R.S., S.P., B.S., S.S., A.P.K. Analyzed the data: B.S., S.P. Wrote the original draft: R.S., A.P.K., S.P. Reviewed, edited, and finalized the draft: B.S., S.S., P.R.S.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shrestha, R., Palaian, S., Sapkota, B. et al. A nationwide exploratory survey assessing perception, practice, and barriers toward pharmaceutical care provision among hospital pharmacists in Nepal. Sci Rep 12, 16590 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-16653-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-16653-x

This article is cited by

-

Evaluation of the knowledge, practices, and attitudes of community pharmacists towards adverse effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): a cross-sectional study

Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.