Abstract

In 2016, China initiated the merge of the urban resident basic medical insurance scheme and new rural cooperative medical scheme into one unified health insurance scheme: the urban and rural resident basic medical insurance. This study investigates the impact of integrated insurance on the direct hospitalization cost of inpatients with catastrophic illnesses. An interrupted time series analysis was conducted based on a sample of 6174 inpatients with catastrophic illness from January 2014 to December 2018. The factors surveyed included per capita total inpatient expense, out-of-pocket expense, and reimbursement ratio. Univariate analysis indicated that after the implementation of the unified urban and rural medical insurance, the reimbursed expense increased from 9398 to 13,842 Yuan (P < 0.001), average reimbursement ratio increased from 0.57 to 0.59 (P < 0.05). Expenses on both western and traditional medicines increased, although the proportion of medicine expense decreased after the integration. Interrupted time series analysis showed that per capita total inpatient expense and per capita out-of-pocket expense increased but showed a gradually decreasing trend after the integration. After the integration of urban and rural medical insurance, the average reimbursement ratio increased slightly, which had limited effect on the alleviation of patients’ financial burden. Furthermore, the integration effect on inpatient expense is offset by increased out-of-pocket medical expense due to suspected supplier-induced demand.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In China, the urban population increased to 56% in 2015, and more than 30% of the residents, or roughly 247 million, living in urban areas are migrants1. A new round of urbanization is underway in China on an unprecedented scale boosted by significant reform on household registration2. The long-lasting and fragmented urban–rural medical insurance systems has become a significant obstacle for migrant population to equally access health services and government subsidies3,4.

There were mainly three basic health insurance schemes in China: the new rural cooperative medical scheme (NCMS, which started in 2003), urban resident basic medical insurance scheme (URBMI, begun in 2007), and urban employee basic medical insurance scheme (UEBMI, launched in 1998). These schemes currently cover over 1.35 billion people (95% of the total population)5. People select health insurance schemes based on their employment status, household registration status (rural or urban), and living locations6. The benefit packages and financial protection are not identical within and across the schemes, hindering universal health insurance coverage in China. The annual per capita fund for UEBMI is approximately 6 and 7 times higher than that for the NCMS and URBMI, respectively7. Furthermore, NCMS is not transferable between provinces. The separated urban–rural health insurances have led to a greater financial burden for vulnerable populations such as rural to urban migrants.

To tackle the inequity caused by the separated insurance schemes, which vary in reimbursement and deductibles, NCMS and URBMI started to merge into one unified health insurance scheme—the urban and rural resident basic medical insurance (URRBMI) in 20168. The current integration focuses on the unification of the capitation, deductible, reimbursement ratio, targeted population, drug catalogs, and the management systems9. The progress of the merge vary from province to province, and in many cities, the funds are still controlled at the county level10.

At present, the main goals of the integration are to increase actual coverage, reduce inequity, improve insurance transfer and unify management systems. However, little is known about the achievement of the goals11,12. In particular, few studies have investigated whether integrated medical insurance reduces out-of-pocket expenditure.

According to WHO, out-of-pocket expenditures in 2011 reached up to over 40% of total health expenditures in China13. For the past decade, the accelerated increase in public funding to subsidize health insurance in China has not lessened the out-of-pocket cost. The increased financial burden of healthcare has worsened the affordability of the vulnerable populations, especially those suffering from catastrophic illness in an underdeveloped region14. A catastrophic illness is a severe disease status requiring continued hospitalization or rehabilitation15. Catastrophic illness has been a substantial financial burden on patients and their families16,17.

This study investigates the impact of integrated urban and rural medical insurance on the direct hospitalization cost of inpatients with catastrophic illnesses. The findings would provide evidence for the improvements brought by URRBMI in China and offer experiences to other countries to tailor their fragmented medical insurance schemes.

Methods

Study region

The study was conducted at Jiujiang in Jiangxi province of China, which is located in southern China. The city has ten counties with a population of 4 million. Before 2016, patients covered by NCMS have reimbursed for all costs (including catastrophic medical insurance) before discharge18. Starting from 2016, integrated urban and rural medical insurance was implemented19. Furthermore, since October 2017, patients in the city were reimbursed for all benefits under a "one-stop instant reimbursement plan" before discharge, including benefits from basic medical insurance, catastrophic medical insurance, complement medical insurance for impoverished populations, and medical assistance from Civil Affairs Bureau20. In addition, local government extracts no less than 5% from the fund pool for catastrophic medical insurance which aims to provide extra reimbursements of high medical expenses21. The deductible of catastrophic medical insurance is determined as 50% of per capita disposable income of Jiujiang, the reimbursement ratio is 60%. The main differences and changes among NCMS and URRBMI in Jiujiang is listed in Table 122,23,24,25.

In this study, we chose one tertiary hospital out of six tertiary hospitals for analysis. The selected hospital was one of the largest hospitals with over 1500 beds.

Data management

Data were retrieved from the hospital information system, containing information on all patients diagnosed with catastrophic illness admitted from January 2014 to December 2018. Catastrophic illness included the following 20 diseases and was covered by both URRBMI and Catastrophic Illness Medical Insurance: acute myocardial infarction, breast cancer, cerebral infarction, cervical cancer, chronic myelogenous leukemia, cleft lip and palate, colon cancer, colorectal cancer, end-stage kidney disease, esophageal cancer, gastric cancer, hemophilia, HIV opportunistic infection, hyperthyroidism, hypospadias, lung cancer, thalassemia, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, severe mental illness, and type I diabetes19.

R package "tidyverse" was used for data cleaning. 5 years data were combined to a single file. 20 catastrophic illnesses were selected by matching the main diagnosis with ICD-10 code. The variables selected for the study included sociodemographic characteristics, length of stay, ICD-10 diagnosis, insurance, medical expense. For medical expense, outliers and missing data were explored. Complete cases were included to the final data. The consumer price index (CPI) of China from 2014 to 2018 was obtained from the World Bank26. All the medical costs were standardized by CPI taking the year 2014 as the reference.

Data analysis

Interrupted time series analysis (ITSA) was used to analyze the effects of integration. ITSA is considered a robust quasi-experimental approach when control groups are lacking. In the interrupted time-series studies, segmented regression analysis is proven effective for estimating intervention effects27,28,29. In this study, the model was constructed as follows:

where Y is the dependent variable representing the reduced percentage of per capita out-of-pocket inpatient expense, the per capita total inpatient expense, and the average reimbursement ratio. Time, integration, and time after integration was considered the independent variables. Time referred to each month from January 2014 to December 2018. Integration was assigned to 0 before the integration (January 2014 to December 2015) and one after the integration (January 2016 to December 2018). Time after integration was assigned to 0 before the integration and increased monthly after the integration (because there were 24 months before the integration and 36 after the integration, the value of this variable after the integration was set from 25 to 60). β0 is the level of explained variables at the beginning. β1 estimates the baseline trend before the integration. β2 estimates the effect of the integration on the change of intercept. β3 reflects the changed trend after the integration (the change in the slope). ε is the error term. All statistical analysis was conducted using R software version 3.5.2. R package "Wats" and "nlme" were used for ITSA, "ggplot2" was used for creating the graphs.

Ethics declarations

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Jiujiang University (REC: JJU20160116).

Patient consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of Jiujiang University, because this study only involved de-identified secondary public access data.

Results

The number of cases with any catastrophic illness before and after the integration in the sampled hospital from 2014 to 2018 is compared in Fig. 1. There were a total of 6174 cases, 2373 (38.6%) before the integration, 3774 (61.4%) after the integration. The top five were cerebral infarction, end-stage kidney disease, lung cancer, gastric cancer, and acute myocardial infarction.

After the integration of urban and rural medical insurance, the reimbursed expense increased from 9398 to 13,842 Yuan (P < 0.001), average reimbursement ratio increased from 0.57 to 0.59 (P < 0.05) (Table 2). Both per capita total inpatient expense and per capita out-of-pocket expense increased significantly, and comprehensive expense (general medical services, such as examination, bed and consultation, etc., and general treatment, such as nursing fees, injection, debridement and suture, dressing change, etc.), diagnostic expense, western medicine expense, and traditional medicine expense. The proportion of western medicine expense and traditional medicine expense decreased after the integration with significant difference.

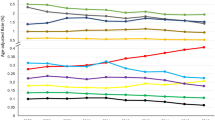

The ITSA indicated that the per capita total inpatient expense increased annually before the integration, but the increases were not statistically significant (Table 3 and Fig. 2). The per capita total inpatient expense increased by ¥3618.7 (P < 0.05) after the integration was implemented. After the integration, the slope of the per capita total inpatient expense decreased by ¥4.3 per month (P = 0.248).

The per capita out-of-pocket inpatient expense increased annually but insignificantly before the integration and increased by ¥1265.6 per month (P = 0.114) after the integration (Table 3 and Fig. 3). After the integration, the slope of the per capita out-of-pocket inpatient expense decreased by ¥1.2 per month (P = 0.479).

The average reimbursement ratio decreased monthly by 0.0002% per month before the reform (P < 0.001). As the reform was implemented, the average reimbursement ratio increased by 0.066% (P = 0.002) (Table 3 and Fig. 4). After the reform, the slope of the average reimbursement ratio increased by 0.0002% per month (P < 0.001).

Discussion

This study evaluated the impact of URRBMI on the hospitalization expense of inpatients due to catastrophic illness in a city fully implemented with URRBMI. As our results showed that the steep decreasing trend of reimbursement ratio was halted and increased gradually right after the integration of urban and rural medical insurance, which was consistent with previous findings, individuals received more inpatient care benefits after the merge of urban and rural medical insurance4. However, our results indicated that the slightly increased average reimbursement ratio was much less than the designed 80% reimbursement ratio of URRBMI23, the actual average reimbursement ratio was still around 59% or even lower30. This is because not all medical services are covered by medical insurance, and the use of drugs outside the reimbursement catalog is not effectively controlled. Therefore, although the average reimbursement ratio is designed at a high level, it couldn't effectively reduce the medical burden of the insured unless it is achieved.

Our results showed that both per capita total inpatient expense and per capita out-of-pocket expense increase after the integration, but the increase is gradually reduced after the integration. To some extent, the integration of urban and rural medical insurance has triggered the release of the medical needs of rural residents31. For example, the average number of outpatient visits increased by 1.4 times, the total medical expenses increased by 35.3%, the inpatient expenses increased by 27.8%, and the outpatient medical expenses increased by 30.4% after the integration30. For patients with catastrophic illnesses, hospitalization and treatment with expensive drugs are needed, resulting in very high medical costs compared with the general population32.

In addition, this study revealed that both western and traditional medicine expenses increased, although the proportion of medicine expenses decreased after the integration. The integration of urban and rural medical insurance has not been able to standardize the profit of public hospitals. For instance, overtreatment due to supplier-induced demand, including unreasonable use of drugs and medical treatment still exists, resulting in increased per capita out-of-pocket expenses for inpatient visits33. Under the current "paying before treatment" plan, patients need to pay all or most of the medical expenses in advance, which further worsens their financial burden34.

Conclusions

After the integration of urban and rural medical insurance, the average reimbursement ratio increased slightly, which had limited effect on the alleviation of patients’ financial burden. Furthermore, the integration effect on inpatient expense is offset by the increased out-of-pocket inpatient medical expense. Thus, policies should be adjusted to defer rising medical needs, use of non-covered drugs, and overtreatment.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, all cases were selected from one tertiary hospital in one city. The conclusions might be difficult to be generalized; Second, several critical independent variables, such as residents' and doctors' satisfaction with the integration and residents' health outcomes, were not included due to limited resources and time; Third, our findings could not entirely reflect the effectiveness of the integrated insurance, because we only showed the change of hospitalization expense, other essential aspects such as insurance coverage and patient satisfaction were not included. However, ITSA was applied in this study, which estimated the level of change after the integration and showed the changing trend that reflects the long-term effect of the integration. Our study provides novel evidence for this research area.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Statistical bulletin of the national economic and social development. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/201602/t20160229_1323991.html (2015).

State Council. State council issued opinions on further promoting reform of household registration system. China. Popul. Today. 5, 3–5 (2014).

Gong, P. et al. Urbanisation and health in China. Lancet 379, 843–852 (2012).

Yang, X., Chen, M., Du, J. & Wang, Z. The inequality of inpatient care net benefit under integration of urban-rural medical insurance systems in China. Int. J. Equity. Health. 17, 173. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0891-0 (2018).

Liu, P., Guo, W., Liu, H., Hua, W. & Xiong, L. The integration of urban and rural medical insurance to reduce the rural medical burden in China: A case study of a county in Baoji City. BMC. Health. Serv. Res. 18, 796. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3611-y (2018).

Qiu, P., Yang, Y., Zhang, J. & Ma, X. Rural-to-urban migration and its implication for new cooperative medical scheme coverage and utilization in China. BMC Public Health 11, 520. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-520 (2011).

Liang, L. & Langenbrunner, J. C. The Long March to Universal Coverage: Lessons from China (World Bank, 2013).

State Council. The State Council’s Opinions on the Integration of the Basic Medical Insurance System for Urban and Rural Residents. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2016-01/12/content_10582.htm (2016).

Shan, L. et al. Dissatisfaction with current integration reforms of health insurance schemes in China: Are they a success and what matters?. Health. Policy. Plan. 33, 345–354. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czx173 (2018).

Yinghui, Q. Study on the Pilot Reform of Merging of China’s Urban and Rural Residents Basic Medical Insurance System (Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, 2015).

Yu-feng, S. Studying on the residents’ satisfaction on integrated medical insurance system in Ningxia. Chin. Health Serv. Manag. 9, 12 (2014).

Tian, Z. Existing problems and countermeasures of the integration of medical insurance for urban and rural residents. Admin. Reform. 2, 36–39 (2015).

Global Health Observatory Data Repository. https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.GHEDOOPSCHESHA2011?lang=en (2011).

Long, Q., Xu, L., Bekedam, H. & Tang, S. Changes in health expenditures in China in 2000s: Has the health system reform improved affordability. Int. J. Equity. Health. 12, 1–8 (2013).

Gillick, M. R., Serrell, N. A. & Gillick, L. S. Adverse consequences of hospitalization in the elderly. Soc. Sci. Med. 16, 1033–1038 (1982).

Kent, E. E. et al. Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care?. Cancer 119, 3710–3717 (2013).

Zhao, S.-W. et al. Effect of the catastrophic medical insurance on household catastrophic health expenditure: Evidence from China. Gac. Sanit. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2018.10.005 (2019).

One-stop reimbursement will be launched for NCMS catastrophic medical insurance in Jiangxi. https://jiangxi.jxnews.com.cn/system/2014/09/04/013306703.shtml (2014).

The implementation plan for integrating basic medical insurance for urban and rural residents in Jiujiang was released. https://jj.jxnews.com.cn/system/2016/08/06/015094569.shtml (2016).

One-stop instant reimbursement came true for all medical insurance in Jiujiang city. https://jj.jxnews.com.cn/system/2017/08/23/016355614.shtml (2017).

Zhong, Z., Jiang, J., Chen, S., Li, L. & Xiang, L. Effect of critical illness insurance on the medical expenditures of rural patients in China: An interrupted time series study for universal health insurance coverage. BMJ Open 11, e036858. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-036858 (2021).

The circular on the issuance of the new rural cooperative medical care compensation plan in 2015. https://www.ganzhou.gov.cn/zfxxgk/c100441gh/201511/a59bc783ef07405a8f5e8af83b771706.shtml (2015).

The NHC on the work of basic Medical insurance for Urban and rural residents in 2018. http://www.nhsa.gov.cn/art/2018/8/14/art_37_316.html (2018).

Jiujiang city integrated urban and rural residents of the basic medical insurance work implementation plan. http://www.pkulaw.cn/fulltext_form.aspx?Gid=18024440 (2016).

Notice on basic Medical insurance for Urban and rural residents in 2017. http://rst.jiangxi.gov.cn/art/2018/2/1/art_47819_3005348.html (2017).

World Bank Global Economic Monitor, China: CPI Price, % y-o-y, seas. adj. https://knoema.com/WBGEM2017Mar/world-bank-global-economic-monitor-monthly-update (2019).

Ramsay, C. R., Matowe, L., Grilli, R., Grimshaw, J. M. & Thomas, R. E. Interrupted time series designs in health technology assessment: Lessons from two systematic reviews of behavior change strategies. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health. Care. 19, 613–623 (2003).

Penfold, R. B. & Zhang, F. Use of interrupted time series analysis in evaluating health care quality improvements. Acad. Pediatr. 13, S38–S44 (2013).

Bernal, J. L., Cummins, S. & Gasparrini, A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: A tutorial. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 348–355 (2017).

Feiyuan, H. & Jiaye, Z. The influence of the integration of urban and rural medical insurance on the utilization of rural residents’ medical services: Taking Guangzhou as an example. Chin. Public Policy Rev. 1, 4 (2017).

Chao, M., Guangchuan, Z. & Hai, G. The influence of the integration of urban and rural medical insurance system on the medical treatment behavior of rural residents. Stat. Res. 4, 78–85 (2016).

Yip, W.C.-M. et al. Early appraisal of China’s huge and complex health-care reforms. Lancet 379, 833–842 (2012).

Si, Y. et al. Comparison of health care utilization among patients affiliated and not affiliated with healthcare professionals in China. BMC. Health. Serv. Res. 20, 1118. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05895-y (2020).

Niu, L. et al. The effect of migration duration on treatment delay among rural-to-urban migrants after the integration of urban and rural health insurance in China: A cross-sectional study. Inquiry 57, 4695. https://doi.org/10.1177/0046958020919288 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Chen Junbo, Li Hui, and other experts for their generous support.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant Numbers 71864020 and The APC was funded by China Medical Board, Grant Number 16-261 and Humanities and Social Sciences Project of Ministry of Education, Grant Number 18YJC840001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W. and L.N.; methodology, L.N.; software, L.N.; validation, L.N., Q.H.S. and X.W.; formal analysis, L.N.; investigation, Q.H.S.; resources, Q.H.S.; data curation, L.N.; writing—original draft preparation, L.N.; writing—review and editing, Q.H.S.; visualization, L.N.; supervision, X.W.; project administration, Y.L.; funding acquisition, L.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Niu, L., Song, Q., Liu, Y. et al. Interrupted time series analysis for the impact of integrated medical insurance on direct hospitalization expense of catastrophic illness. Sci Rep 12, 12316 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-15569-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-15569-w

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.