Abstract

Psilocybin has been shown to be a powerful, long-lasting antidepressant in human clinical trials and in rodent models. Although rodents have commonly been used to model psychiatric disorders, Drosophila have neurotransmitter systems similar to mammals and many comparable brain structures involved in similar behaviors. The forced swim test (FST), which has been used extensively to evaluate compounds for antidepressant efficacy, has recently been adapted for Drosophila. The fly FST has potential to be a cost-effective, high-throughput assay for evaluating potential antidepressants. For this study we pharmacologically validated the fly FST using methamphetamine, DL-α-methyltyrosine, and the antidepressant citalopram. While methamphetamine and DL-α-methyltyrosine altered overall locomotor activity in the Drosophila Activity Monitor System (DAMS), they had no significant impact on measures of immobility in the FST. Conversely, chronic citalopram decreased measures of immobility in the FST in both sexes without increasing DAMS activity. We used the validated FST to evaluate the antidepressant-like effects of high (3.5 mM) and low (0.03 mM) doses of psilocybin. Both doses of psilocybin significantly reduced measures of immobility in male flies, but not females. 0.03 mM had an effect size comparable to chronic citalopram, and 3.5 mM had an effect size approximately twice that of chronic citalopram.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rats are commonly used for behavioral models of human disease states, and have been traditionally preferred to model psychiatric disorders1. Although powerful in behavioral paradigms, rat models have not been developed for extensive genetic remodeling in the way that the classic genetic model, Drosophila melanogaster, has been developed2. Drosophila neurotransmitter systems are remarkably similar to mammalian systems3, they have many comparable brain structures involved in similar behaviors4, and many genes known to influence mammalian behavior are present and performing the same function in Drosophila5. The conservation of neurotransmitter system across phylum manifests as similar responses to drugs6, but Drosophila has not yet been fully utilized for high-throughput behavioral screening of potential pharmacotherapies.

The forced swim test (FST) is a behavioral despair paradigm frequently used in rats to measure coping strategies in response to inescapable adversity, wherein a passive coping strategy (immobility) is interpreted as depressive-like, and reductions immobility as evidence of antidepressant-like effect7,8. The FST can be used to screen for antidepressant action of drugs given to otherwise healthy rats8,9, for passive coping strategies in animal models of depression10,11, or for antidepressant-like effects of drugs given to animals used for the study of depression11,12,13. Although lack of neurocircuit-specific modulations of FST behaviors reduces translational value, due to behavioral sexual dimorphism, the FST is the most reliable measure of depressive-like behavior in both male and female rats9,14. Further, the assay has shown strong face and predictive validity in that risk factors for human depression have repeatedly been shown to increase immobility in the FST11,15, and antidepressant therapies efficacious in reducing human depression also reduce immobility in the FST8,11,15. As the FST measures active and passive coping strategies, it is potentially confounded by non-specific sedative or stimulant effects of drugs that affect overall activity levels7. For example, psychostimulant amphetamine increases active behaviors in the rodent FST along with overall locomotor activity, and antipsychotic sedative chlorpromazine increases immobility in the FST while decreasing overall locomotor activity. However, antidepressant drugs selectively increase active behaviors in the FST without increasing overall locomotor activity7,8. Thus, any investigation into the effects of putative antidepressants requires evaluation of overall locomotor activity to exclude confounding by nonspecific stimulant effects.

Recently, the forced swim test (FST) has been adapted for use in Drosophila16,17. There is evidence that Drosophila exposed to specific stressors display increased immobility in the FST without overall reductions in locomotor activity16,18, suggesting face validity for the fly FST as a measure of behavioral despair, passive coping strategies that are interpreted as depressive-like behavior. However, the fly adaptation of the FST had yet to be pharmacologically validated for predictive validity. The fly FST, if validated, may become a powerful tool for elucidating the pharmacological mechanisms responsible for the effects of antidepressant drugs, and for describing the neurocircuitry involved in changing passive to active coping strategies. Additionally, it has potential to become an extremely cost-effective, high-throughput screening assay for behavioral evaluation of antidepressant-like effects of potential pharmacotherapies, such as psychedelics like psilocybin.

Psychedelic research is currently undergoing a renaissance. Representative compounds have been shown to be powerful, persistent antidepressants in humans19,20,21,22, have antidepressant-like effects13 and to reduce inflammation in rodents23,24,25, and to increase neuroplasticity in larval Drosophila and rodent neuronal cell culture26.

In this study we pharmacologically evaluate the predictive validity of the fly FST using the psychostimulant methamphetamine (METH), the functional sedative DL-α-methyltyrosine (αMT), the established selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant citalopram (CIT), as well as the psychedelic prodrug psilocybin (PSI), the 5-HT1A receptor antagonist WAY 100635 (WAY), and the 5-HT2 receptor antagonist ketanserin (KET). METH increases synaptic activity by reversing the transport direction of the sodium-dependent dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin transporters, and increases Drosophila locomotor activity27. αMT inhibits the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase, resulting in catecholamine depletion, and decreases Drosophila locomotor activity28. CIT selectively inhibits the sodium-dependent serotonin receptor (SERT), and has been shown to bind to SERT in Drosophila (dSERT)29. Psilocybin is converted by alkaline phosphatase to its active metabolite psilocin. Psilocin binds with high affinity to 5-HT2A receptors, and with lower affinity to other serotonergic receptors, including 5-HT1A. Ketanserin and WAY 100635 have both been shown to be bioactive in Drosophila30, and were used to explore the pharmacological mechanism by which psilocybin affects locomotor activity.

Results

Forced swim behaviors and overall locomotor activity vary by sex, strain, and drug response

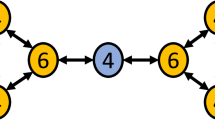

The Drosophila Activity Monitor System (DAMS) was used to measure locomotor activity over time, and the fly forced swim test (FST) was used to measure immobility behaviors in 6-day old males and females of two laboratory standard wild type Canton-Special (CS) flies of distinct lineages. Flies were fed on vehicle medium for 5 days or on a pulsed dose of psilocybin, where the flies fed on psilocybin (0.03 mM) in vehicle medium for 1 day (1×), then vehicle medium for 4 days (Fig. 1).

Experimental design for pulsed (1×) and chronic (5×) dosing. One-day old male and female flies were placed individually into transparent tubes plugged with a loose wad of cotton on one end, and with transparent food medium and a plastic cap on the other end. Food medium was either vehicle, METH (5.0 mM), αMT (3.0 mM), CIT (0.3, 1.0, or 2.5 mM), PSI (0.03 mM, 3.5 mM), KET (1.0 mM), or WAY (1.0 mM). 1× indicates that flies were fed for 24 h on treatment food under group conditions, then transferred into a tube containing vehicle medium (described above). 5× indicates that flies were fed for 5 consecutive days on treatment food in tube as described above. Flies were placed into the DAMS in groups of n = 16 for each sex in each treatment group, and kept at constant light conditions for at least 5 days while being monitored. All other flies were kept under constant light conditions for 5 days, then tested in the FST so that n = 7 for each sex in each treatment group, but the individual data points in the FST represent the mean behaviors of 16 flies. A total of 896 flies were used to generate n = 7 for males (448) and females (448) for each treatment group (112/group).

In the DAMS, a two-way ANOVA for the independent variables sex (male, female) and treatment (vehicle, PSI 0.03 mM) found a significant interaction between sex and treatment (p < 0.0001), as well as significant variation due to sex (p < 0.0001) and treatment (p < 0.0001). CSX females (p < 0.0001) and males (p < 0.0001) fed vehicle medium were significantly more active than same-sex CSCLWU counterparts (Fig. 2A). Both CSX (p < 0.0001) and CSCLWU (p < 0.0001) males were significantly less active than same-strain females. PSI (0.03 mM) increased locomotor activity in CSX females (p < 0.0001), but not in CSX males or CSCLWU flies. No other relevant differences were observed.

Differences in CS sub-strains in the DAMS and FST. The locomotor activity and forced swim responses of 6-day-old flies from two distinct CS lineages (CSCLWU and CSX) were compared under control and PSI (0.03 mM) 5× conditions, 5 days after administration. Data were evaluated using 2-way ANOVA; *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. (A) When fed vehicle medium, CSX flies of both sexes were more active than CSCLWU, and males of both strains were less active than females. PSI increased locomotor activity in female CSX flies. No other relevant differences were observed. (B) CSCLWU males were significantly more immobile than CSCLWU females and CSX males. CSCLWU flies had significantly more bouts of immobility than CSX. No other relevant differences were observed.

In the FST, a two-way ANOVA for the independent variables sex (male, female) and strain (CSX, CSCLWU) found a significant interaction between sex and strain (p = 0.0306), as well as significant variation due to sex (p = 0.0249) and strain (p < 0.0001). CSCLWU males were significantly more immobile than CSCLWU females (p = 0.0115) and CSX males (p < 0.0001), but no differences were observed between male and female CSX flies (Fig. 2B). CSX females (p = 0.0007) and males (p < 0.0001) had significantly fewer bouts of immobility than their same-sex CSCLWU counterparts (Fig. 2B). No other relevant differences were observed.

As CSCLWU flies given 0.03 PSI (1×) were more immobile in the FST and did not increase their overall locomotor activity in the DAMS, that strain was selected for additional experimentation. Additionally, as male CSCLWU flies were significantly (and consistently) more immobile than their female counterparts, sexes were evaluated independently in subsequent FST analyses.

Immobility in the forced swim is independent of overall locomotor activity, and decreased by citalopram

The predictive validity of the fly FST was evaluated by comparing the immobility behaviors of male and female CSCLWU flies fed for 5 days (5×) on vehicle or drug in vehicle medium before being tested for immobility behaviors in the FST. FST behaviors were compared with overall locomotor activity on the fifth day in the DAMS of flies fed on vehicle medium or drug in vehicle medium (Fig. 1). Drugs used were METH (5.0 mM), αMT (3.0 mM), and CIT (0.3 mM, 1.0 mM, 2.5 mM).

Two-way ANOVA for the independent variables sex (male, female) and treatment (vehicle, METH) found a significant interaction between sex and treatment (p = 0.0003), as well as significant variation introduced by both sex (p < 0.0001) and treatment (p < 0.0001). Males fed vehicle medium were significantly less active than females fed vehicle medium (p < 0.0001). METH significantly increased locomotor activity in both males (p < 0.0001) and females (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3A). No other relevant differences were observed.

Locomotor activity as measured by DAMS for METH, αMT and CIT. The changes in overall locomotor activity caused by dopaminergic modulators METH (5.0 mM) 5× and αMT (3.0 mM) 5× were compared with those caused by SSRI CIT (0.3, 1.0, and 2.5 mM) 5×. Data were evaluated with 2-way ANOVA; ****p < 0.0001. (A) n = 16 for each group. Control males were significantly less active than control females. METH significantly increased locomotor activity in both males and females. (B) n = 16 for each group. Control males were significantly less active than control females. αMT significantly decreased locomotor activity in both males and females. (C) n = 16 for each group but females CIT (0.3 mM), in which n = 15. Control males were significantly less active than control females. CIT (2.5 mM) significantly decreased locomotor activity in females, but no other differences were observed among groups.

Two-way ANOVA for the independent variables sex (male, female) and treatment (vehicle, αMT) found a significant interaction between sex and treatment (p = 0.0268), as well as significant variation due to sex (p < 0.0001) and treatment (p < 0.0001). Males fed vehicle medium were significantly less active than females fed vehicle medium (p < 0.0001). αMT significantly decreased locomotor activity in both males (p < 0.0001) and females (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3B). No other relevant differences were observed.

Two-way ANOVA for the independent variables sex (male, female) and treatment (vehicle, 0.3, 1.0, and 2.5 mM CIT) found significant interaction between sex and treatment (p < 0.0001), as well as significant variation introduced by both sex (p < 0.0001) and treatment (p < 0.0001). Males fed vehicle medium were significantly less active than females fed vehicle medium (p < 0.0001). 2.5 mM CIT significantly decreased locomotor activity in females (p < 0.0001), but no other differences were observed among groups. 1.0 mM was chosen for use in the FST (Fig. 2C).

As males were consistently significantly less active at baseline in the DAMS (Figs.2a, 3a–c), FST behaviors of the sexes were evaluated independently using one-way ANOVA. CIT significantly decreased immobility in males (p = 0.0137), increased latency to first immobility in females (p = 0.0227) and males (p = 0.0051), and decreased bouts of immobility in males (p = 0.0285). No significant differences in any outcome measure were observed for either METH or αMT compared to vehicle (Fig. 4).

Use of METH, αMT, and CIT to establish predictive validity of FST. The changes in metrics of immobility in the forced swim caused by dopaminergic modulators METH (5.0 mM) 5× and αMT (3.0 mM) 5× were compared with those caused by SSRI CIT (3.0 mM) 5×. Sexes were evaluated independently with one-way ANOVA and Holm-Sidak post-hoc; n = 7 for each group, and each of 7 data points is the mean of 16 flies. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. CIT significantly decreased male immobility vs vehicle, but no other relevant differences were observed. CIT increased latency to first immobility in females and males vs vehicle, but no other relevant differences were observed. CIT significantly decreased bouts of immobility in males vs vehicle, but no other relevant differences were observed.

Overall locomotor response to psilocybin varies by sex, dose, and dosing strategy

To evaluate the effects of PSI on overall locomotor activity in the DAMS, PSI (0.03 mM, 3.5 mM) was pulse administered (1×) to be consistent with dosing strategies for antidepressant effect in clinical trials21,22 and in research with rats13. Two-way ANOVA for the independent variables sex (male, female) and treatment (vehicle, PSI 3.5 mM, PSI 0.03 mM) found a significant interaction between sex and treatment (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 5A), as well as significant variation due to sex (p < 0.0001) and treatment (p < 0.0001). Control males were significantly less active than females (p < 0.0001). PSI decreased locomotor activity in females at 3.5 mM (p = 0.0011), but increased locomotor activity in males at 3.5 mM (p = 0.0237) and 0.003 mM (p < 0.0001).

Locomotor activity as measured by DAMS for PSI, WAY, and KET. The changes in overall locomotor activity caused by low (0.03 mM) 1× and high (3.5 mM) 1× dose PSI were assessed, as were those caused by PSI (0.03 mM) 5×, WAY (1.0 mM) 5×, and KET (1.0 mM) 5×. Data were evaluated with 2-way ANOVA; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. (A) Female PSI (3.5 mM) n = 15; all other groups n = 16. Control males were significantly less active than control females. 3.5 mM PSI significantly decreased locomotor activity in females. 3.5 mM and 0.03 mM PSI significantly increased locomotor activity in males. No other relevant differences were observed. (B) Female vehicle n = 15; all other groups n = 16. Control males were significantly less active than control females. KET significantly decreased locomotor activity vs vehicle in females vs vehicle and PSI (0.03 mM). PSI, WAY, and KET significantly decreased locomotor activity in males. Both sexes given KET were significantly less active than males given PSI. No other relevant differences were observed.

Chronic and pulsed low-dose psilocybin affect overall locomotor activity differently

To assess whether PSI’s DAMS effects were due to actions at the 5-HT1A or 5-HT2A serotonin receptors, flies were fed for 5 days (5×) on PSI (0.03 mM), WAY (1.0 mM), KET (1.0 mM), or on vehicle medium. Two-way ANOVA for the independent variables sex (male, female) and treatment (vehicle, PSI 0.03 mM, KET 1.0 mM, WAY 1.0 mM) found a significant interaction between sex and treatment (p < 0.0001), as well as significant variation due to sex (p < 0.0001) and treatment (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 5B). Control males were significantly less active than females (p < 0.0001). KET significantly decreased locomotor activity in females (p = 0.0102) and males (p < 0.0001). WAY significantly decreased locomotor activity in males (p = 0.0075) but not females. Females (p < 0.0001) and males (p = 0.0167) given PSI were significantly more active than their same-sex counterparts given KET. No other differences were observed (Fig. 5B).

Psilocybin’s effects on immobility in the forced swim were comparable to those of citalopram

CIT 5 × significantly reduced immobility (p = 0.0004), latency to first immobility (p = 0.0018), and bouts of immobility (p < 0.0001) in males, and significantly reduced latency to first immobility (p = 0.0362) and bouts of immobility (p = 0.0267) in females. PSI significantly reduced immobility at 3.5 mM (p < 0.0001) and 0.03 mM (p < 0.0001), latency to first immobility at 3.5 mM (p = 0.0002) and 0.03 mM (p = 0.0382), and bouts of immobility at 3.5 mM (p < 0.0001) and 0.03 mM (p < 0.0001) in males. No other differences were observed (Fig. 6).

Comparison of PSI with CIT in the FST. The changes in metrics of immobility in the forced swim caused by SSRI CIT (3.0 mM) 5× and 1× were compared with those caused by PSI (3.5 mM) 1× and (0.03 mM) 1×. Sexes were evaluated independently with one-way ANOVA and Holm-Sidak post-hoc; n = 7 for each group, and each of 7 data points is the mean of 16 flies. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. Males given CIT 5×, and both high and low PSI were significantly less immobile than vehicle, but no differences were observed in males given CIT 1× or in any females. Males, and females given CIT 5×, and males given both high PSI and low PSI displayed greater latency to first immobility vs vehicle. Males and females given CIT 5×, and males given both high PSI and low PSI displayed significantly fewer bouts of immobility than vehicle.

Discussion

METH (Fig. 3A) and α MT (Fig. 3A) significantly altered locomotor activity in both male and female flies, but largely did not affect FST behaviors (Fig. 4). Comparatively, CIT (1.0 mM) 5× did not affect locomotor activity in either male or female flies (Fig. 3C), but significantly decreased male immobility, latency to immobility in both sexes, and male bouts of immobility (Fig. 4). Thus, activity in the FST is decoupled from overall locomotor activity, and is selectively modulated by an SSRI antidepressant drug (Fig. 4). Prior work by Araujo, et al. has provided face and some construct validity18, and the results of our study indicate predictive validity for Neckameyer and Nieto-Romero’s Drosophila adaptation of the FST16.

Both high and low doses of PSI 1× profoundly reduced male immobility behaviors in the FST (Fig. 6), but also increased overall locomotor activity in the DAMS. In the typical usage of the FST, antidepressant drugs selectively increase activity in the FST but not overall locomotor activity8. However, in typical usage of the FST, the drug being investigated has been administered within 24 h of testing. In this experiment, PSI was administered for a single day, and then the flies were administered vehicle medium for 4 days prior to testing. As CSCLWU males appear to be exceptionally immobile when compared to females and males of another strain (Fig. 2), increased locomotor activity in both the DAMS and the FST may indicate a gain of function and subsequent normalization of behavior. Supporting this hypothesis, PSI (0.03 mM) 5×, as well as WAY and KET 5× reduced male DAMS activity (Fig. 5B). Chronic antagonism of 5-HT1A receptors by WAY and of 5-HT2 receptors by KET resulted in similar behavioral outcomes as chronic PSI (an agonist at both receptors, which is apparently contradictory. Paradoxically, both agonists and antagonists have been known to downregulate these receptors31,32,33. Thus, the observed reductions in DAMS activity may be consequences of receptor internalization (Fig. 5B).

While the FST has traditionally been an excellent predictor of antidepressant-like activity of investigational drugs, behaviors in the assay are not neurocircuit-specific, and there has been recent controversy regarding its use34. However, Drosophila has been well-developed as a model organism for genetic modulation with low translational value for biomedical purposes. Concurrent use of genetic modulations with behavioral assays validated for Drosophila provides greater translational value and strengthens the integrity of Drosophila as a model organism for biomedical research. So while the Drosophila adaptation of the FST will likely never be used as an independent measure of drug action to determine neural circuitries in mammalian systems underlying the FST, as a complement to investigations of targeted gene expression, the fly FST can help elucidate which genetic modulations are behaviorally relevant and inform on fundamental shared mechanisms of neuronal modulation leading to specific changes in behaviors.

The FST’s use in Drosophila is promising, but some potential confounding factors exist. For example, significant strain and sex differences in baseline locomotor activity (Fig. 2A) and drug response in the FST (Fig. 2B). While some of these differences may be attributable to non-neurological differences, such as females having greater fat deposition and thus greater buoyancy, the extent to which sexually dichotomous neurological differences contribute to behavioral differences has yet to be established. As Drosophila research traditionally uses female flies exclusively in an experiment only when investigating reproductive-related functions, our understanding of sexually dichotomous drug responses is limited. Additionally, the FST uses three different metrics—total immobility, latency to first immobility, and bouts of immobility. While established antidepressant CIT 5× affects each metric in male Drosophila (Figs. 4, 6), they are unaffected in females. How these data are best interpreted is unclear. Further, pulsed dosing of experimental antidepressant PSI 1× has effects similar to, but more pronounced than, CIT 5× (Fig. 6), suggesting that PSI enacts persistent increases in serotonergic signaling. Future directions should include further elucidation of sex differences, as well as neurocircuit-specific investigations using targeted genetic modulations of 5-HT receptors.

Conclusions

We have validated the Drosophila FST for use with CNS-active drugs, in that we have demonstrated that activity in the FST is decoupled from overall locomotor activity as measured by the DAMS, and is sensitive to modulation by SSRI antidepressant citalopram. Chronic exposure to citalopram is necessary to reduce immobility, bouts of immobility, and to increase latency to first immobility. This is similar to SSRI effects in humans, where chronic dosing is necessary to produce an antidepressant effect. Further, the effects of citalopram on measures of immobility are conserved with rodents in the FST. Significantly, we found that psilocybin has an antidepressant-like effect in flies, with at least equal effect size as the antidepressant citalopram at both high and low feeding concentrations. That these effects were long-lasting after a single 24 h exposure, similar to psilocybin’s antidepressant efficacy measured in human clinical trials where effects persist 6 months or more after a single treatment21,22, indicates potential translational relevance for the fly as a model to study psychedelic drug neuropharmacology. Moreover, the fly adaptation of the FST may be suitable for detecting assay-specific behavioral effects of antidepressants and/or antidepressant-like drugs in general, and the assay can be used in complement with neurocircuit-specific studies to elucidate which neurocircuit modulations are behaviorally relevant.

Methods

Experimental design

Groups of one-day old, non-entrained flies were fed for 5 days (5×) on a medium of 1% agarose, 10% sucrose containing METH (5.0 mM), αMT (3.0 mM), CIT (0.3, 1.0, or 2.5 mM), PSI (0.03 mM), WAY (1.0 mM), or KET (1.0 mM) in vehicle medium, or for 1 day (1×) on CIT (1.0 mM) or PSI (0.03 or 3.5 mM), then vehicle medium until testing. Control flies were fed vehicle medium gel consisting of 10% sucrose and 1% agarose (Fig. 1). Flies were observed eating the food under all conditions. Five days after first treatment, 16 male and 16 female flies from each treatment group were evaluated for locomotor activity using the Drosophila Activity Monitor System (DAMS, TriKinetics Inc, Waltham, MA USA), so that n = 16 for each group, excluding individuals that died within the array prior to data collection. For the FST analysis, 5 days after first treatment, seven groups of 16 male and 16 female flies from each treatment group were evaluated in the FST, and the means of each group of 16 flies tested in the FST were used as single data points to represent that population, so that n = 7 for each treatment group (Fig. 1). A total of 896 flies were used to generate n = 7 for males (448) and females (448) for each treatment group (112/group).

Drugs and reagents

Citalopram was chosen as a model antidepressant because it has been shown to bind to the dSERT29, and has previously been used to elicit significant behavioral changes in Drosophila35. Methamphetamine is a psychostimulant shown to increase locomotor activity in Drosophila27 and in rats36. αMT is a tyrosine hydroxylase inhibitor previously shown to reduce locomotor activity in Drosophila28. Psilocybin is an experimental psychedelic shown to have powerful antidepressant effects in humans19,20,21,22 that can be modeled in animals13. Dosage for CIT was determined by guidance from the literature29 and dose–response measuring locomotor activity. Dosage for METH, αMT, PSI, KET, and WAY were determined by guidance from the literature13,28,30,35 and confirmed by previous use in our laboratory27,30.

Flies

Canton-special (CS) flies were used to evaluate the validity of the paradigm within a wild type approximation. Flies were kept under constant light conditions at room temperature to avoid potential circadian-related confounds. Freshly eclosed adult flies were lightly anesthetized with carbon dioxide to be separated by sex into larger storage vials in preparation for placement according to treatment group and assay. As different sub-strains of CS flies have been shown to display locomotor activity differences37, two sub-strains of CS (CSX and CSCLWU) were compared for general locomotor activity and immobility behaviors in the forced swim test, and the sub-strain with greater immobility was selected. CSCLWU flies were originally supplied by Professor Chunlai Wu of the Neuroscience Center of Excellence at the School of Medicine, LSU New Orleans. CSX flies were originally supplied by Dr. Wendi Neckamayer (St. Louis University). Both strains had been cultured in our laboratory for many years prior to this study.

Drosophila Activity Monitor System

One-day old (used in the ‘5×’ 5 day feeding paradigm) or two-day old (used in the ‘1×’ 1 day feeding paradigm) adult flies were briefly anesthetized and placed individually into 5 mm diameter transparent glass or plastic tubes plugged with a loose wad of cotton on one end and capped with transparent food medium containing METH (5.0 mM), α MT (3.0 mM), CIT (0.3, 1.0, or 2.5 mM) on the other end (Fig. 1). The tubes were then placed into the Drosophila Activity Monitor System (DAMS) unit. Each unit contains slots for 32 tubes, with an infrared beam array that monitors beam breaks within each tube using DAMSystem 2 software (TriKinetics Inc, Waltham, MA USA). Locomotor activity for Day 5 is reported as average beam breaks per hour per day.

Methamphetamine

One-day old (5×), non-entrained flies were briefly anesthetized and placed individually into glass DAMS tubes capped with METH (5.0 mM) in vehicle or vehicle food medium, then evaluated in the DAMS for 5 days.

DL-α-methyltyrosine

One-day old (5×), non-entrained flies were briefly anesthetized and placed individually into glass DAMS tubes (previously described) capped with αMT (3.0 mM) in vehicle or vehicle food medium, then evaluated in the DAMS for five days.

Citalopram dose–response

One-day old (5×), non-entrained flies were briefly anesthetized and placed individually into glass DAMS tubes capped with CIT (0.3, 1.0, or 2.5 mM) in vehicle or vehicle food medium, then evaluated in the DAMS for 5 days. The highest CIT dosage that did not affect locomotor activity at Day 5 was chosen for use in the FST.

Psilocybin dose–response

One-day old (1×), non-entrained flies were sorted by sex and fed on PSI (0.03 or 3.5 mM) in vehicle medium for 1 day, then briefly anesthetized and placed individually into glass DAMS tubes capped with vehicle medium, and evaluated in the DAMS until Day 5. Control flies were placed into DAMS tubes with vehicle food on Day 1.

5-HT1A and 5-HT2A antagonists

One-day old (5×), non-entrained flies were briefly anesthetized and placed individually into glass DAMS tubes capped with PSI (0.03 mM), WAY (1.0 mM), KET (1.0 mM) in vehicle or vehicle medium, and evaluated in the DAMS for 5 days.

Forced swim test

One-day old (5×) or 2-day old (1×), non-entrained flies were briefly anesthetized and placed individually into plastic DAMS tubes. The tubes were then placed cotton up into the rack of a 200 mL pipet tip box and left under constant light conditions until Day 5. FST behaviors were evaluated placing one fly per well in 4-well chamber slides containing 1.5 mL 0.08% room temperature SDS in each well16,18. An overhead camera was used to record FST behaviors during the first 5 min in the well for later analysis for latency to first immobility, time spent immobile, and number of bouts of immobility using EthoVision XT 8.5 (Noldus Technology, Leesburg, VA, USA). To verify that the flies were capable of mobility, each fly was gently removed with a spatula and flicked onto a paper napkin after the 5 min of video recording. Any flies unable to immediately walk away from their landing locations were assumed drowned and subsequently excluded from final analysis16.

Validation

Establishing predictive validity for the FST requires demonstrating that immobility behaviors in the FST are decoupled from overall locomotor activity and can be selectively modulated by an established antidepressant drug. We used psychostimulant METH (which increases overall locomotor activity in the DAMS), functional sedative αMT (which reduces overall locomotor activity in the DAMS), and established SSRI antidepressant CIT (at a dose of 1.0 mM that does not affect locomotor activity in the DAMS). One-day old (5×) flies were fed on vehicle or medium containing METH (5.0 mM), αMT (3.0 mM), CIT (1.0 mM) for 5 days, then tested in the FST.

Psilocybin

Using a pulsed dosing strategy, PSI has been shown to be a powerful antidepressant in humans21,22 and to profoundly reduce immobility in rats13, but SSRIs like CIT require chronic administration for antidepressant efficacy in humans. Thus, PSI (0.03 and 3.5 mM) 1× were compared with both CIT (1.0 mM) 1× and CIT (1.0 mM) 5× , with the expectation that CIT 1× flies would not be different from control flies.

Statistical analysis

DAMS and CSCLWU vs CSX FST data were compared using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Holm-Sidak post hoc in Prism software (Graphpad, La Jolla, CA) for the independent variables of sex (male, female) and treatment (vehicle, CIT, METH, α MT, PSI 3.5 mM, PSI 0.03 mM). Other FST data were evaluated using one-way ANOVA, and the sexes were evaluated independently. For the DAMS, n = 16 for all groups, male and female, prior to exclusions. For the FST, n = 7 for all groups, where each data point represents the mean of 16 individuals. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Exclusions

During the CIT dose–response in the DAMS, one female in the 0.3 mM treatment group was dead by Day 5, so for that treatment group n = 15. Immediately following forced swim testing, each fly was scooped out of the well with a small spatula and gently flicked onto a paper towel. Any fly unable to immediately get up and walk away was excluded from analysis and did not contribute to the data or n values presented in this manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Ellenbroek, B. & Youn, J. Rodent models in neuroscience research: Is it a rat race?. Dis. Model. Mech. 9, 1079–1087 (2016).

Prüßing, K., Voigt, A. & Schulz, J. B. Drosophila melanogaster as a model organism for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 8, 35 (2013).

O’Kane, C. J. Drosophila as a model organism for the study of neuropsychiatric disorders. in Molecular and Functional Models in Neuropsychiatry. 37–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2010_110 (Springer, 2011).

Margulies, C., Tully, T. & Dubnau, J. Deconstructing memory in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 15, R700–R713 (2005).

Mohammad, F. et al. Ancient anxiety pathways influence Drosophila defense behaviors. Curr. Biol. 26, 981–986 (2016).

Bainton, R. J. et al. Dopamine modulates acute responses to cocaine, nicotine and ethanol in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 10, 187–194 (2000).

Porsolt, R. D., Le Pichon, M. & Jalfre, M. Depression: A new animal model sensitive to antidepressant treatments. Nature 266, 730–732 (1977).

Slattery, D. A. & Cryan, J. F. Using the rat forced swim test to assess antidepressant-like activity in rodents. Nat. Protoc. 7, 1009–1014 (2012).

Kokras, N. & Dalla, C. Sex differences in animal models of psychiatric disorders. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171, 4595–4619 (2014).

Hibicke, M. Development and Evaluation of an Adolescent Chronic Restraint Stress (ACRS) Protocol to Model Adult Depression in Female Rats (Mercer University, 2017).

Hibicke, M., Graham, M. A. & Hayslett, R. L. Adolescent chronic restraint stress (aCRS) elicits robust depressive-like behavior in freely cycling, adult female rats without increasing anxiety-like behaviors. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 25, 74–83 (2017).

Kandi, P., Hibicke, M. & Hayslett, R. L. Acute cytisine and diarylpropionitrile independently and additively reduce depressive-like behavior in female ovariectomized rats. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. Pharmacol. 2, 250–258 (2015).

Hibicke, M., Landry, A. N., Kramer, H. M., Talman, Z. K. & Nichols, C. D. Psychedelics, but not ketamine, produce persistent antidepressant-like effects in a rodent experimental system for the study of depression. ACS Chem. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00493 (2020).

Dalla, C., Pitychoutis, P. M., Kokras, N. & Papadopoulou-Daifoti, Z. Sex differences in animal models of depression and antidepressant response. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 106, 226–233 (2010).

Kudryashov, N. V., Kalinina, T. S. & Voronina, T. A. Effects of unpredictable chronic mild stress on the effects of antidepressants in the forced swimming test. Neurosci. Behav. Phys. 46, 601–605 (2016).

Neckameyer, W. S. & Nieto-Romero, A. R. Response to stress in Drosophila is mediated by gender, age and stress paradigm. Stress 18, 254–266 (2015).

Neckameyer, W. S. & Bhatt, P. Protocols to study behavior in Drosophila. Methods Mol. Biol. 1478, 303–320 (2016).

Araujo, S. M. et al. Chronic unpredictable mild stress-induced depressive-like behavior and dysregulation of brain levels of biogenic amines in Drosophila melanogaster. Behav. Brain Res. 351, 104–113 (2018).

Jiménez-Garrido, D. F. et al. Effects of ayahuasca on mental health and quality of life in naïve users: A longitudinal and cross-sectional study combination. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–12 (2020).

Palhano-Fontes, F. et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial on the antidepressant effects of the psychedelic ayahuasca in treatment-resistant depression. bioRxiv. 103531. https://doi.org/10.1101/103531 (2017).

Carhart-Harris, R. L. et al. Psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression: fMRI-measured brain mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 7, 13187 (2017).

Griffiths, R. R. et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. J. Psychopharmacol. 30, 1181–1197 (2016).

Nau, F., Yu, B., Martin, D. & Nichols, C. D. Serotonin 5-HT2A receptor activation blocks TNF-α mediated inflammation in vivo. PLoS ONE 8, e75426 (2013).

Flanagan, T. W. et al. 5-HT2 receptor activation alleviates airway inflammation and structural remodeling in a chronic mouse asthma model. Life Sci. 236, 116790 (2019).

Flanagan, T. W. et al. Activation of 5-HT2 receptors reduces inflammation in vascular tissue and cholesterol levels in high-fat diet-fed apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Sci. Rep. 9, 13444 (2019).

Ly, C. et al. Psychedelics promote structural and functional neural plasticity. Cell Rep. 23, 3170–3182 (2018).

Sherman, K. J. Effects of Methamphetamine and Lysergic Acid Diethylamide on Drosophila Behavior—ProQuest (Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, 2016).

Pendleton, R. G. et al. A developmental role for catecholamines in Drosophila behavior. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 81, 849–853 (2005).

Barker, E. L. et al. High affinity recognition of serotonin transporter antagonists defined by species-scanning mutagenesis an aromatic residue in transmembrane domain I dictates species-selective recognition of citalopram and mazindol. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 19459–19468 (1998).

Johnson, O., Becnel, J. & Nichols, C. D. Serotonin 5-HT2 and 5-HT1A-like receptors differentially modulate aggressive behaviors in Drosophila melanogaster. Neuroscience 158, 1292–1300 (2009).

Froger, N. et al. 5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)1A autoreceptor adaptive changes in substance P (neurokinin 1) receptor knock-out mice mimic antidepressant-induced desensitization. J. Neurosci. 21, 8188–8197 (2001).

Assié, M.-B., Lomenech, H., Ravailhe, V., Faucillon, V. & Newman-Tancredi, A. Rapid desensitization of somatodendritic 5-HT1A receptors by chronic administration of the high-efficacy 5-HT1A agonist, F13714: A microdialysis study in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 149, 170–178 (2006).

Gray, J. A. & Roth, B. L. Paradoxical trafficking and regulation of 5-HT(2A) receptors by agonists and antagonists. Brain Res. Bull. 56, 441–451 (2001).

Bale, T. L. et al. The critical importance of basic animal research for neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 44, 1349–1353 (2019).

Yuan, Q., Lin, F., Zheng, X. & Sehgal, A. Serotonin modulates circadian entrainment in Drosophila. Neuron 47, 115–127 (2005).

Rivière, G. J., Byrnes, K. A., Gentry, W. B. & Owens, S. M. Spontaneous locomotor activity and pharmacokinetics of intravenous methamphetamine and its metabolite amphetamine in the rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 291, 1220–1226 (1999).

Colomb, J. & Brembs, B. Sub-strains of Drosophila Canton-S differ markedly in their locomotor behavior. F1000Res 3, 1768 (2015).

Acknowledgements

Figure 1 made with assistance from Mind the Graph. Other figures were created with data originating from this study using GraphPad Prism 9.3.1.

Funding

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health (Grant No. R21DA039462) and Eleusis Therapeutics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H. designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. C.D.N. provided advice and guidance for the experiments and data interpretation, and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved of the manuscript prior to final submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.H. has no competing interests. C.D. Nichols is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of Eleusis Therapeutics, and has a Sponsored Research Contract with Eleusis Therapeutics.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hibicke, M., Nichols, C.D. Validation of the forced swim test in Drosophila, and its use to demonstrate psilocybin has long-lasting antidepressant-like effects in flies. Sci Rep 12, 10019 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14165-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14165-2

This article is cited by

-

The effects of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) on the Positive Valence Systems: A Research Domain Criteria (RDoC)-Informed Systematic Review

CNS Drugs (2023)

-

Probing the antidepressant potential of psilocybin: integrating insight from human research and animal models towards an understanding of neural circuit mechanisms

Psychopharmacology (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.