Abstract

We demonstrate a nanostructure layer made of Ni80Fe20 (permalloy:Py) thin film conjugated MoS2 nano-flakes. Layers are made based on a single-step co-deposition of Py and MoS2 from a single solution where ionic Ni and Fe and MoS2 flakes co-exist. Synthesized thin films with MoS2 flakes show increasing coercivity and enhancement in magneto-optical Kerr effect. Ferromagnetic resonance linewidth as well as the damping parameter increaseed significantly compared to that of the Py layer due to the presence of MoS2. Raman spectroscopy and elemental mapping is used to show the quality of MoS2 within the Py thin film. Our synthesis method promises new opportunities for electrochemical production of functional spintronic-based devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent promising achievements in spintronics specially in magnetic thin films conjugated to two-dimensional (2D) materials has made this topic interesting for fundamental studies to explore their important role in the future spintronic-based memory and computing devices1,2,3,4,5. The core deriving fundamental phenomenon in such structures is the spin–orbit interaction (SOI)6,7. To benefit from SOI in spintronic devices, materials with high spin–orbit coupling (SOC), mostly heavy metals like Pt and Ta8 are used in devices in contact to magnetic thin films. Also, due to the recent developments in the field of 2D materials, special focus is put into implementing 2D materials with their intriguing properties instead of those heavy metals9,10 with high SOC. Many studies have demonstrated the successful usage of transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) in contact to ferromagnetic thin films to enhance the SOI, induce surface anisotropy, etc.11,12. We have recently demonstrated that the magnetic anisotropy can be tuned by MoS2 on the surface of Py thin films13 and also predicted interfacial anisotropy can be changed in Co/black-phosphorene14. Here, we alternatively demonstrate the magnetic properties of Ni80Fe20 change by embodiment of MoS2 thin flakes. This shows the whole single ferromagnetic thin film to possess SOC-induced intrinsic magnetic properties.

Fabrication of thin films for spintronics devices based on physical techniques such as sputtering and thermal evaporation have shown the best performance15,16. Besides, electrodeposition method has established to be very promising in producing spin valves with very high number of layer repetitions (above 100 repeated layers17) and also functional nanowires for spin caloritronic devices18,19,20. Although it should be mentioned that electrodeposition lacks the ability to provide ultra-thin films without voids or making multilayers of diverse types of materials in a single growth21. The implementation of 2D materials in contact to ferromagnetic thin films has been challenging22,23 and such structures are made by transferring the as-made 2D layers on the ferromagnetic layers24. In addition to their multi-step fabrication method, the materials contacts are poor that hitherto limits their reproducibility and scalability25. Therefore, developing new fabrication method for making heterostructure of 2D materials/ferromagnetic layers is demanded to achieve higher yield and functionality.

In this work, we use electrodeposition method for fabrication of Py magnetic films and present the co-electrodeposition of MoS2 thin flakes with ionic elements of the solution. The Raman spectroscopy indicates successful embodiment of thin MoS2 flakes inside the grown magnetic film. The magnetic properties of the layer with MoS2 flakes show prominent differences with bare ferromagnetic layer including higher magnetic coercivity and damping parameter which are directly related to the enhancement in SOC of the medium. Our results indicate that our fabrication method has resulted in a good proximity between the MoS2 and the magnetic material for inducing SOC in the ferromagnet. Our method has the possibility of being used for growth of gradients or multilayers of the investigated material through control of the growth conditions like applied growth voltage/current.

Experimental section

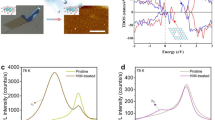

Exfoliation of MoS2

Exfoliation of MoS2 was done for a 1 g MoS2 powder (Aldrich, 99%, < 2 μm) in 100 ml distilled water, equivalent to 10 g l−1 concentrations of MoS2 (Fig. 1a). The MoS2 powder was exfoliated for 4 h using a sonication probe unit equipped with a long step horn tip. In order to avoid excessive heating, the probe of sonic was set to operate 0.7 s and rest for 0.3 s and also an ice-water bath was used during the exfoliation. The resulting solution was centrifuged for 30 min at 200 rpm to remove non-exfoliated particles.

Electrodeposition

Electrodeposition was done from two different solutions. First solution for electrodeposition of the Py sample had the composition of 0.4 M NiSO4.6H2O, 0.04 M FeSO4.7H2O, and 0.4 M H3BO3 (originally prepared from Merk) in distilled water. 200 ml of this solution was used for the electrodeposition. For the electrodeposition of the Py conjugated MoS2 sample (MoS2@Py), second solution was prepared as the following. First a 100 ml of the same solution with doubled molarities was prepared and then a 100 ml of the exfoliated MoS2 solution was added to it. This way the final molarities of Ni and Fe ions is similar in both the solutions. Si substrates (single side polished surface) were cut by 1.5 × 1.5 cm slices. In order to clean surface of the Si from native oxide, they were dipped in 10% HF (hydrochloric acid) solution for 45 s, then washed by ethanol, acetone and distilled water respectively, and dried by air pump. Then the Si substrates were immediately transferred to the electrodeposition cell to prevent further surface oxidation. A two-electrode cell configuration with a DC current source was used for the electrodepositions. A 2 × 1 cm platinized Si was used as the anode and Si substrate as the cathode. The Py and MoS2@Py samples were electrodeposited by applying a direct voltage of 10 V at room temperature during 120 and 150 s, respectively.

Characterization

UV–Visible (Perkin Elmer, Lambda25) and Raman spectroscopy (Teksan) were carried out at room temperature. Surface was probed via atomic force microscopy (AFM, nanosurf) measurement. Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) and elemental mapping were measured by through field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, Hitachi). Magnetic hysteresis loops were measured by longitudinal magneto-optical Kerr effect (MOKE), with a 632 nm laser light (a home-made setup). Ferromagnetic resonance (FMR) measurements were performed by a home-made field modulation lock-in technique at the frequency range of 2–20 GHz (for details see supporting information).

Results

Schematic of the exfoliation condition is depicted in Fig. 1a where the force of water molecules results in exfoliation of the MoS2 powder into thin flakes. To characterize the quality of the exfoliated MoS2 in water, UV–Visible absorption measurement was used. Result of this measurements can be seen in Fig. 1b. The A and B peaks at 559 and 663 nm respectively are the characteristic of few layer MoS2 dispersions. After solution preparation and electrodeposition of the layers (Fig. 1a below) Raman characterization is used to see if the MoS2 flakes are imbedded in the body of the Py layer. Figure 1c presents the Raman spectrum for Py and MoS2@Py samples. Raman peaks at 379 and 403 cm−1 clearly show the presence of MoS2 flakes in the electrodeposited layer26. The bare Py sample shows no peak in its Raman spectrum because it has a metallic nature.

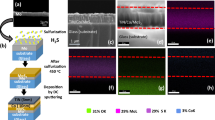

The surface topography of the Py and MoS2@Py samples has been observed with AFM and presented in Fig. 2a and b, respectively. The AFM images show that both samples have a similar surface structure with an increased mean surface roughness for the MoS2@Py sample to 45 nm from the 20 nm mean surface roughness of the Py sample. Also, FESEM characterization of the Py and MoS2@Py samples has been performed and results are presented in Fig. 2c and d, respectively. It can be seen that both the samples have a granular structure with an increased grain size for the MoS2@Py sample. Also cross sectional FESEM images of the samples are presented in supporting information which show thicknesses of ~ 50 and ~ 100 nm for Py and MoS2@Py samples (~ 10% error), respectively. The observed higher thickness of the MoS2@Py samples is related to the partial space occupation by MoS2 and also the slightly higher electrodeposition time of this sample. Distribution of MoS2 in Py layer has been evidenced by EDX measurement. Figure 2e–h represents the EDX mapping of Ni, Fe, Mo and S elements where the uniform color distribution shows the uniform embodiment of MoS2. Also, the atomic ratio of Ni:Fe is 4:1.

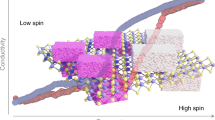

In continue, magnetic properties of the samples are investigated through the MOKE and FMR measurements. Longitudinal MOKE measurement results are presented in Fig. 3a showing that both the samples have an in-plane magnetic anisotropy. Two prominent differences are appeared in the MOKE signal of the samples. One is the much higher coercivity (Hc) of the MoS2@Py sample which is depicted in Fig. 3b. The Hc for the Py sample is ~ 10 Oe and has increased to ~ 30 Oe for the MoS2@Py sample which is equivalent to a 300% increase. In the case of films, the magnetic anisotropy of ferromagnetic layers has been demonstrated to change by proximity to TMDC layered materials due to the d-d hybridization at the interface11,13,14. In the case of MoS2@Py sample, all interfacial directions between Py and MoS2 is possible which overall has resulted in the observed in-plane coercivity change. Generally, magnetic anisotropy is highly dependent on the SOC27,28,29 and by addition of MoS2 as a material with high SOC to the layer, changes in the magnetic anisotropy is expected. One should note that increase of the in-plane coercivity can result from the increase of thickness because of the emerging out of plane magnetic anisotropy component at higher thicknesses30,31,32,33,34. To see if the observed increase of Hc in our samples is due to the relatively higher thickness of the MoS2@Py sample we performed MOKE measurements for different thicknesses of Py layer and only a slight change in the Hc was observed (for the details see supporting information). Therefore, we conclude that the observed changes in the magnetic properties of Py is due to its proximity to MoS2. Also, the Hc of the samples can be affected by the grain size35 and the AFM and SEM images indicate a comparably bigger grain size for the MoS2@Py sample. But the totally different MOKE signal quality of the MoS2@Py sample, including the slope of the plot, indicates that presence of MoS2 is playing a crucial role in this increased Hc.

The other observation from the MOKE signal is the much higher signal intensity of the MoS2@Py sample relative to Py sample which is increased by 275%. Two mechanism can play role in the observed MOKE signal increase for the MoS2@Py sample: (1) increase of the saturation magnetization (Ms) and (2) increase of light interaction with matter36,37. Here the increase of the MOKE signal cannot be due to the increase of MS, as the MS decreases for the MoS2@Py sample (See FMR section). Therefore, increase of the MOKE signal can be related to the increased interaction between light and the MoS2@Py sample. For the case of multilayered ferromagnet/TMDC heterostructures it has been reported that proper thickness, refraction index and incident angle, can form a cavity38,39. Here we achieved enhancement of the MOKE signal via composing MoS2 flakes with the magnetic layer. Enhancement of light-mater interaction also has been achieved via electrophoretic deposition of MoS2 nanostructures40. Simulation of the MOKE signal for the composed MoS2@Py sample are encouraged to obtain the optimized composing structure. Also, we do not ignore the possibility of the larger grain size in the MoS2@Py being responsible partially for the observed MOKE signal intensity increase. For determining the exact contribution of each parameter further experiments should be designed.

We have also measured the FMR characteristics of the samples to see how MoS2 can affect the magnetization dynamics of the Py layer. The spin dynamic response of the samples investigated at different constant microwave frequencies ranging from 2 to 20 GHz and by sweeping H from 0 to 4500 Oe. The observed FMR spectra were fitted with the derivative of Lorentzian function to determine the resonance field (Hr) and FWHM (∆H) at each frequency. Figure 3c presents the measured FMR signal of the samples (dots) and their fit (solid line) at f = 14 GHz. The frequency dependence of Hr for the Py and MoS2@Py samples can be seen in Fig. 3d (dots). The solid lines in this figure are the fitted data by Kittel’s equation. Dependence of the FMR frequency on the external magnetic field for thin films assuming with infinite dimensions which are saturated in the plane can be described by Kittel formula41,

where \({\upmu }_{0}\) is the permeability of the free space, \(\gamma\) is the gyromagnetic ratio (28 GHz/Tesla), H is the external magnetic field and \(H_{k}\) is the uniaxial anisotropy field which is negligible for Py films with low thickness. The resulted MS from this fit are 10,448 and 9391 Oe for the Py and MoS2@Py samples, respectively. A decrease of about 10% in the Ms of the MoS2@Py sample is observed which can be understood via the nonmagnetic character of the MoS2 that results in a lower magnetization per unit volume. Also, both samples do not show magnetic anisotropy. By using the damping relation42, as the following:

and fitting the data we can calculate the damping parameter of the samples. Here ΔH0 is the inhomogeneous broadening, and \(\alpha\) is the Gilbert damping parameter. The fitting of the data based on this equation can be seen in Fig. 3e. The value of ΔH0 for Py and MoS2@Py samples are 114 and 231 Oe respectively. All the obtained parameters from the FMR data are presented in Table 1.

In the obtained results, we see a doubling of the damping coefficient in the MoS2@Py sample compared to the Py sample, which has increased from 0.018 to 0.023. There are many reports that show the coating of a nonmagnetic layer on a ferromagnetic layer can lead to the enhancement of the damping parameter43,44,45. Several mechanisms have been proposed for the enhancement of damping parameter in such bilayers. SOC and interfacial d-d hybridization cause the enhancement of the intrinsic damping, while extrinsic enhancement of the damping can arise from two-magnon scattering processes, due to roughness and defects at the interface region46,47,48. In the case of our sample, embodiment of MoS2 in the Py layer results in the increased interfaces between Py and MoS2 and therefore both intrinsic and extrinsic contribution can contribute in the observed increase of the damping parameter. Moreover, the coupling between a FM layer and an adjacent NM layer can enhance the effective damping of the magnetization precession via spin-pumping effect44,49. For example, many groups have recently demonstrated the generation of spin–orbit torque in devices made with the Py/WTe250, CoFeB/MoS2 or WSe251, and Py/MoS252 and the reciprocal process (voltage generation from spin-pumping) in MoS2/Al/Co heterostructures53. In the case of our MoS2@Py sample we observe the phenomena via enhanced damping parameter in a relatively thick magnetic layer thanks to the embodiment of the MoS2 flakes inside the layer which gives a high contact surface area between MoS2 and Py.

Conclusions

MoS2 was successfully embodied within the structure of the Py magnetic thin film by electrodeposition method. The layer with MoS2 flakes shows a higher magnetic coercivity and Gilbert damping parameter, indicating the proper bonding between the MoS2 and the magnetic material. In addition, the cavity of light in the MoS2@Py sample resulted in a three-fold increase of the MOKE signal which opens a pathway for the research on the optimization of MOKE sensors and also fundamental studies in the field. Due to the capability of applying our method for a large set of ferromagnetic/TMDC materials, there is a great potential for further development of functional spintronic and magnonic devices.

References

Vega, V., Ferna, A., Prida, V. M., Salaheldeen, M. & Me, M. Tuning nanohole sizes in Ni hexagonal antidot arrays : Large perpendicular magnetic anisotropy for spintronic applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.8b02205 (2019).

Ahn, E. C. 2D materials for spintronic devices. NPJ 2D Mater. Appl. 4, 1–14 (2020).

Lin, X., Yang, W., Wang, K. L. & Zhao, W. Two-dimensional spintronics for low-power electronics. Nat. Electron. 2, 274–283 (2019).

Avsar, A. et al. Colloquium: Spintronics in graphene and other two-dimensional materials. Rev. Mod. Phys. 92, 021003 (2020).

Salaheldeen, M., Martínez-Goyeneche, L., Álvarez-Alonso, P. & Fernández, A. Enhancement the perpendicular magnetic anisotropy of nanopatterned hard/soft bilayer magnetic antidot arrays for spintronic application. Nanotechnology 31, 485708 (2020).

Premasiri, K. & Gao, X. P. A. Tuning spin–orbit coupling in 2D materials for spintronics: A topical review. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 31, 193001 (2019).

Shi, S. et al. All-electric magnetization switching and Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction in WTe2/ferromagnet heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 945–949 (2019).

Manchon, A. et al. Current-induced spin–orbit torques in ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 035004 (2019).

Husain, S. et al. Emergence of spin–orbit torques in 2D transition metal dichalcogenides: A status update. Appl. Phys. Rev. 7, 41312 (2020).

Ramaswamy, R., Lee, J. M., Cai, K. & Yang, H. Recent advances in spin–orbit torques: Moving towards device applications. Appl. Phys. Rev. 5, 031107 (2018).

Zhang, W. et al. Ferromagnet/two-dimensional semiconducting transition-metal dichalcogenide interface with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy. ACS Nano 13, 2253–2261 (2019).

Polesya, S., Mankovsky, S., Ködderitzsch, D., Bensch, W. & Ebert, H. Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interactions and magnetic texture in Fe films deposited on transition-metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Status Solidi Rapid Res. Lett. 10, 218–221 (2016).

Jamilpanah, L., Hajiali, M. & Mohseni, S. M. Interfacial magnetic anisotropy in Py/MoS2 bilayer. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 514, 167206 (2020).

Hoseyni, S. H., Rahimi, K., Barakati, B., Sadeghi, A. & Mohseni, S. M. Magnetic anisotropy in Co/phosphorene heterostructure. Phys. E Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 128, 114620 (2021).

Salaheldeen, M. et al. Tailoring of perpendicular magnetic anisotropy in Dy13Fe87 thin films with hexagonal antidot lattice nanostructure. Nanomaterials https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8040227 (2018).

Hierro-Rodriguez, A. et al. Revealing 3D magnetization of thin films with soft X-ray tomography: Magnetic singularities and topological charges. Nat. Commun. 11, 6382 (2020).

Bakonyi, I. & Péter, L. Electrodeposited multilayer films with giant magnetoresistance (GMR): Progress and problems. Prog. Mater. Sci. 55, 107–245 (2010).

da Santa Clara Gomes, T. C., Abreu Araujo, F. & Piraux, L. Making flexible spin caloritronic devices with interconnected nanowire networks. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav2782 (2019).

Abreu Araujo, F., da Câmara Santa Clara Gomes, T. & Piraux, L. Magnetic control of flexible thermoelectric devices based on macroscopic 3D interconnected nanowire networks. Adv. Electron. Mater. 5, 1800819 (2019).

Piraux, L., da Câmara Santa Clara Gomes, T., Araujo, F. A. & de la Torre Medina, J. 3D magnetic nanowire networks. In Magnetic Nano- and Microwires (ed. Vázquez, M.) 801–831 (Elsevier, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-102832-2.00027-x.

Torabinejad, V., Aliofkhazraei, M., Assareh, S., Allahyarzadeh, M. H. & Rouhaghdam, A. S. Electrodeposition of Ni–Fe alloys, composites, and nano coatings—A review. J. Alloys Compd. 691, 841–859 (2017).

Megra, Y. T. & Suk, J. W. Adhesion properties of 2D materials. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 52, 364002 (2019).

Torres, J., Zhu, Y., Liu, P., Lim, S. C. & Yun, M. Adhesion energies of 2D graphene and MoS2 to silicon and metal substrates. Phys. Status Solidi Appl. Mater. Sci. 215, 1700512 (2018).

Sklenar, J. et al. Perspective: Interface generation of spin–orbit torques. J. Appl. Phys. 120, 7514–7520 (2016).

Lv, W. et al. Electric-field control of spin–orbit torques in WS2/permalloy bilayers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 2843–2849 (2018).

Windom, B. C., Sawyer, W. G. & Hahn, D. W. A Raman spectroscopic study of MoS2 and MoO3: Applications to tribological systems. Tribol. Lett. 42, 301–310 (2011).

Scherer, D. D. & Andersen, B. M. Spin–orbit coupling and magnetic anisotropy in iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 037205 (2018).

Jansen, H. J. F. Magnetic anisotropy in density-functional theory. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 59, 4699–4707 (1999).

Shick, A. B., Khmelevskyi, S., Mryasov, O. N., Wunderlich, J. & Jungwirth, T. Spin–orbit coupling induced anisotropy effects in bimetallic antiferromagnets: A route towards antiferromagnetic spintronics. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 81, 212409 (2010).

Miao, G., Xiao, G. & Gupta, A. Variations in the magnetic anisotropy properties of epitaxial CrO2 films as a function of thickness. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 71, 1–7 (2005).

Ingvarsson, S., Xiao, G., Parkin, S. S. P. & Gallagher, W. J. Thickness-dependent magnetic properties of Ni81Fe19, Co90Fe10 and Ni65Fe15Co20 thin films. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 251, 202–206 (2002).

Walsh, F. C. Overall rates of electrode reactions. Faraday’s laws of electrolysis. Trans. Inst. Met. Finish. 69, 155–157 (1991).

Arregi, J. A., Riego, P. & Berger, A. What is the longitudinal magneto-optical Kerr effect?. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 50, aa4ea6 (2017).

Barker, D. & Walsh, F. C. Applications of Faraday’s laws of electrolysis in metal finishing. Trans. Inst. Met. Finish. 69, 158–162 (1991).

Yusrini, M. & Iskandar, I. Y. Influence of grain size on magnetic properties of electroplated NiFe. Key Eng. Mater. 328, 381–384 (2006).

Haider, T. A review of magneto-optic effects and its application. Int. J. Electromagn. Appl. 7, 17–24 (2017).

Boardman, A. D. & King, N. Magneto-optics and the Kerr effect with ferromagnetic materials. In Tutorials in Complex Photonic Media 57–79 (SPIE, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1117/3.832717.Ch3.

Ghasemi, R. et al. Electrical and magneto-optical characterization of Py/MoS2 bilayer: A facile growth of magnetic-metal/semiconductor heterostructure. Mater. Lett. 265, 127454 (2020).

Baradaran Ghasemi, A. H., Faridi, E., Ansari, N. & Mohseni, S. M. Extraordinary magneto-optical Kerr effect via MoS2 monolayer in Au/Py/MoS2 plasmonic cavity. RSC Adv. 6, 106591–106599 (2016).

Mosconi, D. et al. Site-selective integration of MoS2 flakes on nanopores by means of electrophoretic deposition. ACS Omega 4, 9294–9300 (2019).

Kittel, C. On the theory of ferromagnetic resonance absorption. Phys. Rev. 73, 155–161 (1948).

Kalarickal, S. S. et al. Ferromagnetic resonance linewidth in metallic thin films: Comparison of measurement methods. J. Appl. Phys. 99, 1–7 (2006).

Azzawi, S. et al. Evolution of damping in ferromagnetic/nonmagnetic thin film bilayers as a function of nonmagnetic layer thickness. Phys. Rev. B 93, 054402 (2016).

Tserkovnyak, Y., Brataas, A. & Bauer, G. E. W. Enhanced Gilbert damping in thin ferromagnetic films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 117601 (2002).

Barati, E., Cinal, M., Edwards, D. M. & Umerski, A. Gilbert damping in magnetic layered systems. Phys. Rev. B 90, 014420 (2014).

Lenz, K. et al. Two-magnon scattering and viscous Gilbert damping in ultrathin ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 73, 144424 (2006).

Sun, Y. et al. Damping in yttrium iron garnet nanoscale films capped by platinum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 106601 (2013).

Rojas-Sánchez, J.-C. et al. Spin pumping and inverse spin Hall effect in platinum: The essential role of spin-memory loss at metallic interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 106602 (2014).

Tserkovnyak, Y., Brataas, A. & Bauer, G. E. W. Spin pumping and magnetization dynamics in metallic multilayers. Phys. Rev. B 66, 224403 (2002).

MacNeill, D. et al. Control of spin–orbit torques through crystal symmetry in WTe2/ferromagnet bilayers. Nat. Phys. 1, 300–305 (2016).

Shao, Q. et al. Strong Rashba–Edelstein effect-induced spin–orbit torques in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenide/ferromagnet bilayers. Nano Lett. 16, 7514–7520 (2016).

Zhang, W. et al. Research update: Spin transfer torques in permalloy on monolayer MoS2. APL Mater. 4, 032302 (2016).

Cheng, C. et al. Spin to Charge Conversion in MoS2 Monolayer with Spin Pumping 1–15. arXiv:1510.0345 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge (Iran National Science Foundation (INSF) under Grant 97001939 and Iran Science Elite Federation (ISEF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Y.V.: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing—original draft. L.J.: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Supervision; Validation; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. M.Z.: Data curation; Methodology. S.M.M.: Conceptualization; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Roles/Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yousef Vand, M., Jamilpanah, L., Zare, M. et al. Magnetic NiFe thin films composing MoS2 nanostructures for spintronic application. Sci Rep 12, 9809 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14060-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14060-w

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.