Abstract

Between the Last Glacial Maximum and the mid-Holocene, the Mediterranean Sea experienced major hydrological changes. The deposition of the last sapropel, S1, during the Early Holocene is a consequence of these changes. In order to cause anoxia in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea (EMS) bottom water, a long preconditioning period of a few thousand years would need to occur throughout the deglaciation prior to S1. It is generally believed that this freshwater was of North Atlantic origin, later supplemented by the African Humid period (AHP). Here, we investigate another potentially important source of freshwater to the EMS: the Fennoscandian ice sheet (FIS) meltwater, running into the Caspian and Black Seas. A few scenarios of continental hydrologic perturbation have been developed to drive a high-resolution Mediterranean Sea general circulation model. We demonstrate that, during the last deglaciation, FIS meltwater flowing into the Black Sea reduced surface salinity and ventilation over the main convection areas in the EMS. By including continental hydrological changes, a more consistent framework is produced to characterize the hydrology of the Mediterranean Sea during the last deglaciation and the Early Holocene.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sapropel occurrence in the Mediterranean has a strong correlation with regional hydrologic perturbations driven by precession cycles of the Earth’s orbit and is characterized by increased African monsoon run-off and enhanced freshwater input from the Nile River1,2. Recent sapropels, such as S1 and S5, have been shown to be initiated by the precession cycle (~ 21 ka periodicity) and modulated by the glacial-interglacial cycle (100 ka)3. A modeling investigation successfully simulated the protracted oxygen depletion leading to the S1 onset (~ 3.5 ka in the Ionian and the Levantine basin, for instance) within a numerical Mediterranean general circulation model coupled with its biogeochemical components4. A preconditioning period throughout the deglaciation is believed essential for bottom water anoxia to occur. The massive influx of low-salinity Atlantic water from Heinrich stadial 1 (HS1, 18–15.5 ka), entering the Mediterranean Sea through the Gibraltar Strait, combined with high biological productivity, drastically modified the ventilation and caused the development of anoxia within the Eastern Mediterranean Sea (EMS)4.

The Gibraltar Strait, however, may not be the only route by which the deglaciation affected the EMS. A complementary source could be continental. Fennoscandian ice sheet (FIS) meltwater could have reduced the salinity of the Black Sea5,6,7,8 and the Marmara Sea9,10, ultimately impacting the Aegean Sea’s surface salinity, stratification and convection.

Here, based on recent findings in Eastern European deglaciation hydrology5,7,10,11,12,13,14,15,16, we elaborate different scenarios of continental hydrologic perturbations affecting the EMS. Using a numerical model of the Mediterranean Sea, we further quantify their impact and discuss their plausibility in light of proxy-evidence.

Sediments and stratigraphy evidence from the Caspian basin show that large flooding fed by FIS melting occurred (in Ponto-Caspian) from 17 to 10 ka, with an overflow to the Black Sea from 16 to 14 ka13 (Fig. 1). This finding was further confirmed by studies suggesting that the Ponto-Caspian basin collected meltwater and trapped fine-grained sediment transported from the southeastern margin of the FIS during the deglaciation (mainly through the Dnieper and Volga rivers)7.

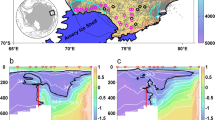

Map of LGM ice caps including the Fennoscandia Ice Sheet67 and its southward drainage basin with major rivers indicated, including the Volga, Don, and Dnieper68,69. The red contour shows the surface area (1,119,166 km2) from which meltwater potentially flows into the Black Sea and Caspian Sea. The anomalous sea surface salinity from the “17mSvFIS” experiment (averaged over the last 10 years) is overlaid for the Mediterranean. Crosses indicate the location of marine cores evoked/used in this study: SL152 (40°05.19′N, 24° 36.65′E; water depth: 978 m)15,21, SL148 (39°45.23′N, 24°05.78′E; water depth: 1094 m)18,19,20, LC21 (35°39.7′N, 26°35.0′E; water depth: 1520 m)3, SL123 (35°45.3′N, 27°33.3′E; water depth: 728 m)20, MD84-641 (33°02′N, 33°38′E; water depth: 1375 m)58, MS27PT (31°47′N, 29°27′E; water depth: 1389 m)40,41, MD90-917 (41°17′N, 17°36′E; water depth: 1010 m)55 and MD07-2797 (36°57′N, 11°40′E; water depth: 771 m)56,57. The map has been generated using ArcGIS. Bathymetric data sets come from the GEBCO 2014 bathymetric grid (both ocean and land terrain, https://www.gebco.net).

Isotopic studies on the Black Sea (also referred to as the ‘Neoeuxine Lake’) reveal a northern freshwater source but diverge on the timing, attributing it to either a series of meltwater pulses17 between 16.5 and 14.8 ka BP or repeated seasonal bursts of ~ 220 years from cyclic drainage of Lake Disna over successive periods between 17.5 and 15.5 ka6. Sediment studies further suggest massive meltwater input to the Black Sea between 16.4 and 15.4 ka BP (greater than 25,000 km3)8. It is suggested that this meltwater volume would fill both the Caspian an Black Seas8, leading to flooding and outflowing. Regarding stratification, a different timing is proposed: the Black Sea could have overflowed during HS1, associated with low stratification of the basin5, or during the Younger Dryas (YD, 12.8–11.6 ka)17. The study of Major et al.14 combining proxy data and shallow- or deep-sill (Bosphorus) scenarios proposes the following chronology. Between 25 and 13.4 ka, the Black Sea overflowed for the two sill types. From 13.4 to 12.8 ka, it overflowed for the deep-sill model but not for the shallow-sill model. Between 12.8 and 11 ka, the Black Sea did not overflow for the shallow model while it is “possible” that it did for the deep-sill model. Between 11 and 10 ka, overflowing was likely for the shallow-sill model and reasonably certain for the deep-sill model14. A recent reconstruction of Black Sea paleosalinity suggests an overflow to the Marmara Sea from 23 to 14.7 ka, but not during the Bølling‐Allerød (BA, 14.7–12.9 ka) and the YD, due to surface salinity increase (associated with higher evaporation) of the Black Sea16.

In the Marmara Sea, data for the last deglaciation are scant. However, it appears, based on δ18O records, that a hydrologic connection persisted from the LGM to the end of the YD, likely indicating an outflow to the Marmara Sea, assuming a Black Sea level (BSL) close to the Bosphorus sill depth9. It is also proposed that freshwater inflow to the Marmara Sea could occur from 50 ka and persist continuously until 14.7 ka10.

Conversely, oceanic proxy data studies over the Aegean Sea do not seem to converge regarding substantial freshwater input from the Black Sea during the last deglaciation. The LC21 core, located in the south of the Aegean Sea with a continuous δ18O record from 150 ka BP to present, shows a drop of ~ − 2‰ in δ18O during HS1 (between 16 and 15 ka). However, the authors of the study do not firmly attribute this decrease to meltwater inputs3. It is also interesting to mention a rich compilation of cores in the Aegean Sea that suggest a reduction in local deep-water formation and the prevalence of eutrophic conditions at the SL148 core (in the north) during the BA. This condition was attributed to increased riverine nutrient flux18, probably due to incoming deglaciation meltwater from the northern borderland mountains (Rhodope glacier)19,20 or increased precipitation in the northern borderland for the SL152 core (North Aegean)21. In the SL123 core (South Aegean), a relatively small reduction in deep water oxygenation is recorded during the BA20. However, a recent reconstruction of sea surface salinity (SSS) in the SL152 core showed a decrease of ~ − 1.5 PSU between 11 and 10 ka associated with the freshwater outburst from Lake Agassiz15.

Finally, the recent study by Aksu and Hiscott11 reviewed the available data over the last 20 years and proposed a multi proxy analysis of the BSL and Marmara Sea level during the last deglaciation. They find a Black Sea outflow to the Aegean Sea during 17.2–15.7 cal ka over the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles sills due to the FIS melting. During the BA, based on the Dardanelles sill depth and Marmara sea-level reconstructions, the first incursion of Aegean/Mediterranean water into the Marmara Sea would be dated at 14.7 ka9 (with a sill depth of – 80 m22) or at 13.8 ka (− 75 m)11. Over this period and until the end of the YD at least, the Aegean Sea flowed into the Marmara Sea. After 12.5 ka, outburst floods from lakes in the Altay and Sayan Mountains of Central Asia may have contributed to the BSL rise, leading to outflowing into the Aegean Sea from 11.1 to 10.2 ka11.

In summary, several studies based on paleo data indicate that the Caspian and Black Seas were filled with FIS meltwater either through outburst/flooding (likely from 17 to 10 ka for the Caspian Sea and between 17.5 and 14.8 ka for the Black Sea) or through continuous melting until the YD. Moreover, the Black Sea collected the majority of freshwater from the Caspian Sea7,13,23,24.

A review of previous studies on the Marmara and Black Seas in the period 21–10 ka suggests that FIS meltwater would lead to an outflow from the Black Sea to the Aegean Sea, at least from the LGM to 14.7 ~ 13.4 ka firstly, and then from 12 to 11 to 10 ka. During most of the BA and YD, an outflow to the Aegean Sea is unlikely due to higher evaporation leading to increased salinity of the Black Sea (potentially associated with a lower BSL).

Aegean Sea studies suggest an inflow during the BA, but linked to nearby regional meltwater inputs. This mismatch between studies focusing on the north of the Dardanelles Strait on the one hand, and the south on the other hand, shows that there is still a lack of understanding of the chronology and quantification of potential freshwater outflow from the Black Sea during the last deglaciation.

Our goal is to revisit the hypothesis of freshwater brought by glacial melting of FIS to the EMS (Fig. 1). Using high-resolution regional oceanic modeling, we assess the impact of this meltwater discharge into the EMS and discuss to what extent proxy data can attest to this Black Sea freshwater outflowing.

Results

Freshwater flux reconstruction from Fennoscandia to the Bosphorus Strait

To investigate the effect of FIS melting on the EMS via Black Sea freshening, we use a three-step approach. First, we quantify the meltwater flux from the FIS into the Caspian and Black Seas catchments using ice sheet reconstructions25,26,27. Second, by using transient simulations of the last deglaciation, we estimate the water budget over the Black Sea for this period. Deducting this budget from the FIS meltwater, we compute the BSL evolution and the outflow over the Bosphorus sill. Third, we use numerical modeling to examine the effect of the meltwater on the SSS, stratification and ventilation of the EMS. The high spatial resolution of the Mediterranean Oceanic Regional Circulation Model (ORCM), NEMOMED8, does not allow us to perform transient simulations from the LGM to Early Holocene. To overcome this issue, we extract the most significant phases of the Black Sea outflowing based on proxy studies. Then, we imposed the fluxes as boundary conditions on the ORCM28 and ran different experiments (of 100 years each) (see the “Materials and methods” section for a detailed description of ice sheet reconstruction and experimental design). Finally, we put the Black Sea outflow into perspective regarding ORCM output and the proxy data which show freshwater perturbation affecting the EMS.

The three ice sheet reconstructions we used, ICE-6G26, GLAC-1D27 and Patton et al.25, rely on different methods. ICE-6G uses Global Positioning System measurements and space geodesic constraints. GLAC-1D reconstruction is based on ice-sheet modeling using climate simulations. Patton et al.’s reconstruction uses a thermomechanical model with regional constraints.

The reconstructed volume of ice in the Black and Caspian Seas catchments and the associated meltwater flux show several phases from 21 to 10 ka (Fig. 2a). Between 20.5 and 15 ka, the ice mass loss of 23% to 26% of its 20.5 ka total is equivalent for all ice-sheet reconstructions. The associated meltwater flux increases between LGM and 16.5 ka. The mean flux over this period is 1.7, 2.2 and 2.6 mSv for ICE-6G, GLAC-1D, and Patton, respectively. At the BA onset, it abruptly increases following the ice mass loss. The maximum meltwater flux at that period is 17, 29 and 37 mSv for ICE-6G, GLAC-1D, and Patton, respectively. The flux then decreases until the end of the YD with a final increase until the FIS vanishes completely. The meltwater flux obtained here, especially for the BA, can be compared to those established in previous studies. The value of 50,000 m3 s−1 transferred from the Caspian Sea to the Black Sea (50 mSv) is based on lake levels and stratigraphy during the early and middle stages of deglaciation (17 to 14 ka)13 and is higher than the first pulse indicated by our reconstruction. Another study based on estimated river paleodischarge and ice sheet flow estimated a Caspian flooding to the Black Sea of ~ 23,000 km3 over 20–30 years (~ 29 mSv) around 15.5 ka12, which fits with the magnitude of our reconstructed meltwater fluxes.

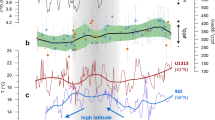

(a) Ice sheet reconstructions from three different sources with the volume of ice (plain curves, left axis) and associated meltwater flux (dashed curves, right axis) potentially draining to the Caspian Sea and Black Sea catchment. “A”13 and “1”12 represent meltwater-driven flux reconstructions from the Caspian Sea to the Black Sea. (b) Black Sea level (right axis, m, relative to modern sea level) and associated volume changes (left axis, km3) deduced from the Black Sea’s water budget with FIS meltwater input as shown in panel a), and the regional water flux P–E (precipitation-minus-evaporation) from two transient simulations of MIROC4m and Trace-21 ka. The water volume is expressed as the complementary volume needed to reach the Bosphorus sill at − 37 m, the level necessary for the Black Sea to outflow to the Mediterranean. The lowest BSL at the LGM is estimated to be – 105 m29,30 and the total volume for outflowing to occur is 29,675 km3 (light blue horizontal patch). Superimposed are BSL reconstructions by Lericolais et al.29, Genov30 and Aksu and Hiscott11. The reconstruction by Aksu and Hiscott (2022) suggests a Black Sea outflowing from 17.2 to 15.7 ka over the uppermost “Pleistocene delta Δ2” (− 55 m) as inferred from seismic reflection. (c) Black Sea freshwater outflowing (red, blue, and green) over the Bosphorus sill, as a result of (a) and (b). The black plain line marked with “B” represents an estimation (in mSv) by Chepalyga13. Black dots (marked with “a” and “b”) represent other two estimations for 15 ka at the Bosphorus Strait31. The horizontal plain lines represent the chronology reported in previous studies for Black Sea outflowing to the Marmara Sea (purple) and the Aegean Sea (orange). Blue patches represent the scenarios of the present study carrying out hosing experiments with a regional oceanic model: “4mSvFIS” (12,614 km3 of additional freshwater over 100 years) and “17mSvFIS” (53,611 km3 over 100 years).

The Black Sea water budget throughout the deglaciation is sensitive to P–E (positive P–E for TraCE-21 ka and negative P–E for MIROC4m, Supplementary Information). We evaluated in the Supplementary Information the likeliness of each combination. The most likely combination involves the average of P–E between TraCE-21 ka and MIROC4m, as shown in Fig. 2b. The BSL and associated volume changes show different behaviors depending on the ice sheet reconstructions. All the reconstructions have a rapid transgression phase starting from the LGM BSL (~ − 105 m29,30). Once the Bosphorus sill depth is reached for ICE-6G, the reconstruction, weighted by Black Sea P–E, shows overflowing from 19 to 10 ka. For GLAC-1D and Patton, the estimated BSL is punctuated by several regression and transgression phases. From 17 ka onwards, GLAC-1D experiences a first regression up to − 90 m at 16.5 ka, a second regression up to − 70 m at 15 ka and a last one at 12.5 ka up to 70 m. Patton shows a first regression phase up to − 120 m at 15 ka and a second up to − 90 m at ~ 12 ka.

To evaluate the likeliness of these scenarios in terms of sea-level amplitude, we represent the BSL as reconstructed by Lericolais et al.29, Genov30 and Aksu and Hiscott11. According to Lericolais et al., after a transgression phase (starting from − 105 m during the LGM), the BSL reaches the Bosphorus sill (close to − 37 m) from 16.5 to 13 ka, followed by a regression phase from 13 to 10 ka. According to Genov, after a long transgression phase, the BSL would reach the Bosphorus sill depth at 11.7 ka until 10.5 ka. According to Aksu and Hiscott11, the LGM BSL is higher (− 90 m). From 17.2 to 15.7 ka, Black Sea outflows over the uppermost “Pleistocene delta Δ2” (− 55 m)11 of the Bosphorus sill, and after 15.7 ka a regression phase occurs up to − 110 m around 14.7 ka. Then, the BSL increases until 11 ka when it reaches the shallowest sill depth. Our BSL based on ice sheet reconstructions shows a different timing than that of the previous reconstructions. However, the amplitude is comparable, especially for the regression phases.

Finally, we estimate the freshwater flux overflowing the Bosphorus sill (Fig. 2c). Between 20.5 and 15 ka, the average flux is 1.3, 1.9, 2.2 and 1.7 mSv for ICE-6G, GLAC-1D, Patton, ICE-AVERAGE, respectively. Abrupt melting occurs at ~ 14.5 ka for Patton et al., 14 ka for ICE-6G and 14.2 ka for GLAC-1D. The associated flux is 16, 28, 34 and 19 mSv for ICE-6G, GLAC-1D, Patton, ICE-AVERAGE, respectively. This event is followed by a quasi-continuous decrease reaching another peak (11.5 ka in Patton et al., and 11 ka for ICE-6G, GLAC-1D and ICE-AVERAGE) until the ice sheet vanishes completely. Over the period 11–10 ka, the average flux is 3.2, 2, 4.6 and 3.3 mSv for ICE-6G, GLAC-1D, Patton, ICE-AVERAGE, respectively.

Chepalyga (2007) estimated a flux of 60,000 m3 s−1 (60 mSv) from the Black Sea to the Marmara Sea, between 17 to 14 ka13 which is higher than our suggested flux. Another study using hydrological data and theoretical considerations of hydrometeorological watershed31 conditions shows a 15-ka pulse of either 200 km3 year−1 (~ 6.3 mSv) or 450 km3 year−1 (14.3 mSv) depending on the methodology. The second estimation agrees with the 14-ka peak in ICE-6G.

In terms of timing, at the early deglaciation stage, our reconstruction indicates an overflowing between 19.5 and 16.5 ka while most of the previous proxy-based studies suggest the 16.6–14.7 ka range. The BA meltwater pulse is inexistent in previous studies, mainly because of higher evaporation in the Black Sea and its catchment during this period. However, regarding the previous flux quantifications13,32, it is likely that our calculation of the BA-peak equates with the 16.6–14.7 ka outflowing phase. The post YD-peak, based on our calculations and previous studies would be the most likely outflowing phase.

We therefore propose an ensemble of forcing conditions to mimic different continental freshwater perturbations of the EMS. They constitute compromises between our climate forcings for the Early Holocene, our computation limitations, and our estimates of Black Sea outflow. We target the overflows during the BA with the “17mSvFIS” experiment and after the YD (“4mSvFIS”, Fig. 2c). In addition, we suggest the Nile River reached its highest activity after the YD due to last African Humid period33,34 and propose the “4mSvFIS + 9kNile” experiment. After the FIS melted completely, we also simulate “9kNile”, where the Nile River is considered to be the major freshwater contributor to the EMS.

Impact on the EMS assessed with high-resolution modeling

The Early Holocene standard experiment (“9kstd”) simulates high SSS (38 to 39 PSU, increasing eastward) in the EMS due to high evaporation (Fig. 3). The stratification index (IS) and the mixed-layer depth (MLD) both depict areas of convection in the Aegean Sea (~ 0.3 m2 s−2 over the sea and 160–200 m in the south), North Levantine (0.6 m2 s−2 and 100–200 m), south Adriatic (0.6 m2 s−2 and between 400 and 500 m) and north Ionian Seas (0.3 m2 s−2 and up to 700 m). These surface and subsurface behaviors and properties are characteristic of the EMS in Mediterranean models without any massive freshwater input under either Early Holocene atmospheric conditions4 or present-day conditions4,35,36,37. They are quite close to data observed for the present day38,39.

Output of the oceanic model: from left to right, columns are sea surface salinity (PSU), index of stratification (IS, m2 s−2), and mixed layer depth (m). The top row shows their climatological distributions in the “9kstd” simulation, and the remaining rows (from top to bottom) show the anomalies in each of the perturbation simulations. All simulations are at equilibrium. Figures show the average over the last 10 years. Figure have been generated using the Basemap package from Matplotlib (https://matplotlib.org/basemap).

The Black Sea outflow experiments (“4mSvFIS” and “17mSvFIS”) significantly reduce the SSS in the Northern Aegean Sea (− 2.1 and − 7 PSU for “4mSvFIS” and “17mSvFIS”, respectively, with a north–south gradient, Fig. 3 and Table 1). The freshening also impacts the Eastern Levantine (− 0.3 and − 0.5 PSU for “4mSvFIS” and “17mSvFIS”, respectively) and the Adriatic (− 0.2 PSU for “4mSvFIS” and “17mSvFIS”). “9kNile” shows a negative SSS anomaly that spreads westward following the coastline quite uniformly (− 1.7 PSU) over the most eastern part of the Levantine, and then over the Aegean (− 0.6 PSU in the Northern part), Northern Ionian, and Adriatic Sea (− 0.3 PSU). The combined experiment, “4mSvFIS + 9kNile”, depicting the additive effect of “4mSvFIS” and “9kNile”, produces a decrease in SSS at the Nile mouth (East Levantine: − 1.7 PSU) and over the Aegean Sea (northern part: − 2.6 PSU) and restricted to − 0.5 PSU elsewhere (with a similar pattern as “9kNile”).

Black Sea outflow experiments indicate a large decrease in oceanic convection potential and deep-water formation, characterized by increasing IS. In “4mSvFIS”, the Aegean, Eastern Levantine, South Adriatic, and North Ionian show a similar increase between + 1 and + 1.5 m2 s−2, whereas the western Levantine and Northern Ionian show decreasing IS (as much as − 1.5 m2 s−2, due to the slowdown of the zonal overturning circulation transporting low-salinity water masses from the western basin). In “17 mSv”, almost the entire EMS shows an increasing IS (up to + 2 m2 s−2 more pronounced over the Eastern Levantine, South Aegean, and Northern Ionian). Consequently, all intermediate and deep-water formation spots are affected in almost equal measure in “4mSvFIS” and “17mSvFIS”. The MLD is lifted up to − 100/− 200 m in the Aegean Sea, − 100 m in the Levantine (over a larger area in “17mSvFIS”) and − 500 m in the Southern Adriatic/Northern Ionian (also a more extended area in “17mSvFIS”). In “4mSvFIS + 9kNile”, the spatial structure and intensity of the IS anomaly is similar to “17mSvFIS”, although less extensive with an average value of ~ 1 m2 s−2. The MLD reduction pattern and values in this simulation are similar to those of “4mSvFIS” and “17mSvFIS” but are more widespread over the easternmost coast.

Placing these results in the context of the last deglaciation, the “9kstd” simulation represents the reference state. The anomalies of this simulation are compared to “17mSvFIS” where the flux linked to the BA meltwater pulse has a decreased ventilation mainly in the Adriatic/Ionian basins compared to the “4mSvFIS”. The remaining flux (~ 4 mSv) is superimposed on the Nile effect “4mSvFIS + 9kNile”) between the YD and the end of the deglaciation. In “4mSvFIS”, the SSS decrease is comparable to the decrease observed in SL15215 between 11 and 10 ka (simulation: − 2.1 PSU, observations: − 1.5 PSU, Table 1). After the FIS completely vanishes, the Nile in “9kNile” becomes one of the major sources of freshwater continuing to perturb the convection and ventilation of the EMS.

Discussion

Black Sea outflow may affect the EMS at the BA onset and after the YD, although proxy-based data are not unanimous in confirming this north freshwater influence. How reliable are these experiments documenting extensive meltwater influx to the Aegean Sea and the EMS? The main argument against meltwater affecting the Aegean Sea (and the Marmara Sea) is the relatively weak δ18O depletion recorded in planktonic foraminifera which would belie meltwater intrusion.

To discuss this issue, we compare our Black Sea outflow estimations with proxy data from the EMS. First, we calculate the sea-water δ18O (δ18Ow), an estimate of the freshwater effect on three marine cores over the Central Mediterranean (MD042797, Sicily Strait), and the EMS (MD90-917, Adriatic Sea and MD84-641, Eastern Levantine) (Fig. 4b). Second, we document the chronology of Nile activity, the major freshwater contributor to the EMS, based on the deltaic core, MS27PT, from the middle stage of deglaciation to the Early Holocene. The reliability of the sediment core MS27PT in monitoring past Nile hydrology and reconstructing the African Humid Period in the Nile basin has been demonstrated in several sedimentology and geochemistry studies34,40,41. The ratio of Ti/Ca reflects the relative proportions of Nile terrestrial versus marine inputs at high temporal resolution. The sedimentation rate coupled with neodymium isotopes (expressed as εNd) are tracers of fluvial Nile activity (cf “Materials and methods”).

(a) Black Sea outflow chronology as calculated in this study (repetition of Fig. 2c). (b) δ18Ow from 21 to 10 ka in marine cores MD90-917 (41°17′N, 17°36′E; water depth: 1010 m, South Adriatic Sea55), MD07-2797 (36°57′N, 11°40′E; water depth: 771 m, Strait of Sicily56,57) and MD84-641 (33°02′N, 33°38′E; water depth: 1375 m, Eastern Levantine basin58). (c) Sedimentation rate, clay-εNd (fraction lower than 2 micron) in MS27PT (31°47′N, 29°27′E; water depth: 1389 m, Nile delta), decimal logarithm of the Ti/Ca ration scanned with XRF in MS27PT.

From 20 to 10 ka, δ18Ow records from the Sicily Strait and the South Adriatic Sea display a similar pattern indicating surface waters salinity fluctuations. An initial δ18Ow decrease between 20 and 16 ka marks the late glacial period followed by a deglaciation rise in δ18Ow, more pronounced in the Sicily Strait, until the start of the BA at 14 ka. Between 14 and 12 ka, δ18Ow values decrease before rising until the onset of the Holocene at 11.7 ka. A final drop in δ18Ow characterizes the Early Holocene in both basins until 10 ka, suggesting the arrival of less saline surface waters. In contrast, in the Eastern Levantine, the δ18Ow record displays different behavior marked by a progressive decreasing trend (by 2.5 ‰) that lasted from 17 ka until 10 ka.

Between 14.8 and 5.5 ka, during the AHP, the northward migration of the rainfall belt in Africa enhanced precipitation in North Africa34,42,43,44. The massive reactivation of fluvial systems led to intensified precipitation in the Nile catchment and a massive inflow of freshwater to the EMS. In a recent study41, the record of suspended matter discharge from the Nile floods, indirectly linked to the freshwater input of the Nile, has been revisited using the Nd isotopes measured on the clay fraction to improve the reliability of the Nile fluvial activity records (cf “Materials and methods”).

The downcore evolution of clay-εNd is in phase with the ratio of Ti/Ca as well as with sedimentation rates (Fig. 4). This reflects low Nile fluvial activity during the LGM and the HS1. From 14.8 ka onwards, the three proxies agree and indicate a progressive increase in Nile fluvial activity, interrupted by the YD. This onset of Nile activity at 14.8 ka is also concomitant with an increase in organic component indicating higher terrigenous input from the Nile basin34.

Combining these proxies, we can conclude that Nile River intensification resulting from the AHP enhancement started between 15.7 and 14.5 ka and reached its highest activity between 12 ~ 10 and 6 ka. The δ18Ow decrease observed throughout deglaciation in the Eastern Levantine appears to face with our calculations of Black Sea freshwater outflow: δ18Ow decrease starts from 17 ka at the peak of the first phase which occurred between 19 and 16.5 ka. The decrease then became more pronounced from 14.5 ka with the BA-peak.

In contrast, in all freshwater scenarios, our results indicate a salinity increase in the Western Ionian and the Strait of Sicily (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Moreover, δ18Ow fluctuates more in the Adriatic and Sicily cores than in the Eastern Levantine core. The salinity increase in the ORCM in the Sicily is due to the reorganization of surface currents following massive freshwater inputs45. Thus, another pattern can be expected, consistent with the increase of δ18Ow. The relative large δ18Ow increase in the Sicily Strait between ~ 16 to 14 ka could coincide with BA-peak meltwater. In the Adriatic, although the ORCM indicates homogenous salinity decrease, the IS differs locally (increase to decrease stratification compared to “9kstd” Fig. 3), especially at the location of the MD84-641core. Here, δ18Ow increase between 15.5 and 14 ka might coincide with the BA and the end of the YD when δ18Ow abruptly increased conjointly with the Black Sea outflow. However, a local freshwater explanation (the melting of the Alps, for instance) is more likely.

In the North Aegean Sea, the reconstructed SSS in the SL152 core shows a decrease between 11 and 10 ka similar to the salinity anomaly in the “4mSvFIS” experiment and is assumed to reflect the Black Sea outflowing during this period (SL152: − 1.5 PSU, “4mSvFIS”: − 2.1 PSU).

On the other hand, some studies propose that the freshening of the EMS occurring during the HS1 is due to the increasing exchange rate at the Strait of Gibraltar since the LGM4,46. Moreover, the rapid sea-level rise, especially during meltwater pulses, invigorated the water mass exchange at the Strait of Gibraltar, thus enhancing the freshening of the EMS46. The global sea-level rise is also consistent with the δ18Ow decrease. Our study does not refute this hypothesis but complements this approach with additional evidence on regional freshwater input.

Finally, we focus on ventilation which is sensitive to freshwater perturbation through water stratification changes. δ13C records in benthic foraminifera can give some insights in this regard, being a proxy of ventilation and of biological productivity. Results of benthic foraminiferal δ13C from various sites in the EMS reveal a decreasing trend in ventilation from the end of H1 until 9 ~ 8 ka, with a rapid drop during the BA and after the YD4,18,20,47. In our simulations, the impact on the MLD, and, thus, on the intermediate and deep ventilation, is quite similar, i.e., the enhanced freshwater input from the Black Sea has the same “dynamic” impact as the enhanced Nile input. The δ13C drop during the BA would be in line with our reconstructed Black Sea outflow. Nevertheless, the post-YD δ13C drop is more difficult to link to the Black Sea outflow than to the intensified Nile fluvial activity that occurred at the same period41. Moreover, our experimental configuration does not permit us to indicate if the decrease in ventilation following Black Sea outflow could have persisted for thousands of years, thus allowing water stagnation and low benthic foraminiferal δ13C.

Conclusions

We identify in this study a plausible role of FIS melting in the freshening of the EMS through the Black Sea. The FIS evolution shows nonlinearity and the meltwater flux is punctuated by at least three phases during the deglaciation.

We quantify the potential effect of FIS meltwater on the EMS. Our work reveals a high sensitivity in the EMS circulation and shows that Black Sea freshwater input played a significant role in reducing the SSS and ventilation of the EMS. This effect is important when combined with enhanced freshwater input into the EMS due to a strengthened African Monsoon, leading to an additional decrease in salinity and convection in the EMS.

Our results are consistent with proxy data recorded in the Black Sea and the Marmara Sea for the early and late deglaciation but not during the BA period. Moreover, a certain divergence remains with marine proxies in the Aegean Sea and more generally in the EMS: the enhanced freshwater during the deglaciation may not be attributed to meltwater from the Black Sea but rather to the global sea-level rise. Nevertheless, our work complements the existing hypothesis which relies on long-term dynamics of the Atlantic Ocean and on variations in the water properties at the Strait of Gibraltar.

The Black Sea hydrology throughout the last deglaciation deserves more careful analysis of FIS melting, the changes in precipitation-driven river discharges and the complex geomorphology of the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits. A joint inventory of these contributions considering both a modeling approach and proxy evidence is crucial to accurately quantify the Black Sea outflow to the Marmara and the Aegean Sea. Usually neglected, they may additionally contribute to the S1 preconditioning in the EMS, as is suggested for the Aegean Sea11.

Materials and methods

Estimation of the meltwater influx to the Black Sea and Caspian Sea catchments

Three sources are used to estimate the meltwater flux. The first is the ICE-6G reconstruction26 recording the global ice sheet evolution from 24 to 8 ka with a 500-year time step between 21 and 10 ka. ICE-6G uses Global Positioning System observations augmented by additional space geodetic constraints such as sea-level from complementary systems. The second source is the GLAC-1D reconstruction27 which is based on a set of glaciological models derived from plausible climate forcing of PMIP1 and PMIP2 LGM simulations. GLAC-1D data are provided with a frequency of 100 years. For the sake of simplicity, we extract the ice volume with a time step of 500 years from 21 to 10 ka. The time step is refined to 200 years between 16 and 13 ka, with the first melting maximum expected during the BA. For both ICE-6G and GLAG-1D, we adjust the thickness of the FIS before computing the ice volume taking the isostasy into account. We then estimate the potential flux of meltwater directed to the Caspian and Black Seas through the Volga, Don, and Dnieper rivers. The third source is the reconstruction by Patton et al.25, recording the FIS evolution with a 50-year time step based on a 3-dimensional thermomechanical ice sheet model. In Patton et al.’s model, the temperature and precipitation adjust to the evolving ice sheet surface through the applied lapse rates derived from multiple regression analyses of meteorological observations. Moreover, the regional reference climates and associated forcing are tuned independently for each of the three major ice accumulation centers (of the Eurasian ice sheet complex) to account for the large variation in climate regimes across the Eurasian domain. Patton et al.’s reconstruction shows the entire FIS chronology (1 dimension), with a maximum volume of 3.7 106 km3 reached at 22.8 ka. Data from ICE-6G and GLAC-1D (providing 3-D reconstruction) are processed with Integrated Geo Systems to show the expected ice volume and meltwater directed to the Black Sea and Caspian Sea catchments. From 23 ka, both GLAC-1D and ICE-6G show a maximum volume of 1.2 106 km3 (at 21 ka for GLAG-1D and 20 ka for ICE-6G) in the selected area. To ensure a direct comparison between the three datasets, we simply divide Patton et al.’s data by a factor of 3 in our calculation.

Estimation of the Black Sea outflow

From the FIS reconstructions, we evaluate the BSL evolution from the LGM and the likely freshwater outflow over the Bosphorus sill to the Marmara Sea. First, we use recent simulations of the last deglaciation from MIROC4m48, an atmosphere–ocean coupled general circulation model (AOGCM), and TraCE -21ka49 to give an estimation of precipitation (P) and evaporation (E) over the Black Sea during this period. The simulation of the last deglaciation was performed under fixed LGM ice sheets and time-evolving orbital parameters. The TraCE-21 ka dataset contains output from the full TraCE-21 ka simulation from 22,000 years before present (22 ka) to 1990 CE. The model (CCSM3) was forced with transient greenhouse gas concentrations and orbitally driven insolation changes. Transient boundary conditions include the ICE-5G ice sheets extent and topography and changing paleogeography with sea level rises from its Last Glacial Maximum level to modern level. The P–E from MIROC4m and TraCE-21 ka is presented in the Supplementary Information. Second, we represent the BSL reaching the Bosphorus sill and the associated volume changes. As the Bosphorus sill depth during the last deglaciation is open to debate11, for the sake of simplicity and to avoid overestimation, we consider that the Black Sea outflows when the sea level reaches the shallow sill in the Southern Strait of Bosphorus (− 37 m today). To estimate the volume needed for outflow to occur from the LGM BSL, we take account of the modern Black Sea area (436,400 km2). As estimating BSL is highly sensitive to P–E, we consider every combination, including a bias correction of P-E relative to modern observations. To evaluate the plausibility of each scenario, we compare them with BSL reconstructions11,29,30. As two reconstructions29,30 are in 14C age, we use the Black Sea reservoir age estimated by Soulet et al.5 to estimate the calibrated age (shown in the Supplementary Information). Finally, we choose the P–E combination that reflects a sea-level amplitude similar to the reconstruction and deduce the associated outflow. The selected scenario takes the average of MIROC4m P–E (bias corrected, P–E negative) and TraCE-21 ka (unbiased, P–E positive).

Description of the oceanic model

The Ocean Regional Climate Model, NEMOMED850,51, is the Mediterranean version of the NEMO ocean modeling platform52. The horizontal domain includes the whole Mediterranean Sea and the near Atlantic Ocean serves as a buffer zone. The horizontal resolution is 1/8° in longitude and 1/8°cosφ in latitude, approximately 9 km to 12 km from north to south. Vertically, the model has 43 layers of inhomogeneous thickness. Represented in the model are 33 river mouths. The Black Sea is considered to be a river flowing into the Aegean Sea. All simulations are analyzed at their equilibrium state over the last 10 years of simulation.

Atmospheric forcing

The atmospheric forcing driving NEMOMED8 was derived from the Mediterranean regional simulation of the Early Holocene period (9.5 ka), corresponding to the last insolation maximum, performed with a sequential global-regional modeling procedure, LMDZ-NEMO-med-v128. This architecture is based on the IPSL-CM5 global simulation (Coupled Model Intercomparison Project protocol)53. The 30-year atmospheric forcing is the same for each simulation and is used in a loop to force, with sea-surface temperature (SST), wind stress, P minus E, solar flux, and total heat flux, the 100-year Mediterranean oceanic circulation experiments.

Freshwater forcing

The different simulations only differ in the fluvial input applied. “9kStd” is a virtual configuration with preindustrial river runoff54. “9kNile” uses the Early Holocene Nile enhancement provided by LMDZ-NEMO-med-v128. This reconstruction uses the continental hydrological budget over the Nile catchment to provide a climatological signal. With this setting, the Early Holocene Nile has a mean runoff of approximately 15 mSv (3 mSv for the pre-damming value). For the Black Sea outflow experiments (“4mSvFIS”, “17mSvFIS”), we use fluxes as presented in the results. Freshwater perturbations have been applied at the Bosphorus Strait uniformly over the year.

Sea surface water δ18O calculation

Three deep-sea cores have been selected for the δ18O (δ18Ow) calculation: MD90-917 (41°17′N, 17°36′E; water depth: 1010 m55), MD07-2797 (36°57′N, 11°40′E; water depth: 771 m56,57) and MD84-641 (33°02′N, 33°38′E; water depth: 1375 m58) collected in the South Adriatic Sea, in the central part of the Strait of Sicily and in the Levantine basin, respectively.

SSS as expressed by local sea-water δ18Ow was determined following the method of Duplessy et al.59. Combining both planktonic foraminiferal δ18O and SST reconstructions55, we derived the sea-surface δ18Ow by solving the paleotemperature equation of Shackleton60:

Variations in δ18Ow reflect both the global mean oceanic isotopic composition related to continental ice volume changes and local changes due to freshwater inflow variations and evaporation balance. Local δ18Ow changes were obtained by subtracting the effect of continental ice melting from global sea-water δ18O. The latter is assumed to be equal to the deglaciation sea level curve61,62 multiplied by a constant coefficient of ~ 1.05‰ as per Duplessy et al.63. We did not convert the δ18Ow values into salinity units because of uncertainty resulting from possible temporal changes in the slope of the δ18Ow /salinity relationship at the studied core site64. The accuracy of the δ18Ow estimates depends primarily on the SST estimates, given that there is a 0.07‰ error due to mass spectrometer measurements and the mean standard deviation on SSTs (~ 1 °C error for SST estimates would result in a 0.2 ‰ error in the calculated δ18Ow value).

εNd, sedimentation rate and Ti/Ca evolution in MS27PT

The MS27PT sediment core (31°47′N, 29°27′E; water depth: 1389 m) located in the Nile deep-sea fan is directly influenced by Nile freshwater input and provides a continuous record of fluvial sediment discharge from the Nile River basin for the last 110 ka40,41. This is well illustrated by high-resolution XRF core scanner log (Ti/Ca) ratios which reflect varying proportions of terrestrial to marine inputs following the insolation. The Nile watershed is essentially composed of two main catchments, both of silicate lithology: the Ethiopian highlands, or traps, mainly composed of basaltic volcanic rocks and drained by the Blue Nile and the Atbara rivers and the Equatorial craton, mainly composed of gneiss and granulite rock and drained by the White Nile. Sediment Nd isotopic compositions (expressed using the epsilon notation εNd) are little affected by weathering processes and hence faithfully reflect geographical provenance and crustal age of the source rocks65. Thus, the Nile basin is well suited to isotopic tracer analysis because of the contrasting εNd signatures characterized by the Cenozoic Ethiopia traps (εNd ~ 0) and the Precambrian Central Africa Craton (εNd ~ − 30). The sediment loads of each tributary have a distinct Nd isotopic composition reflecting the geology of the catchments. Thus, temporal changes in both Nd signature and sedimentation rate allow changes in the terrigenous contribution relative to spatial precipitation changes34 to be reconstructed. Recently, the use of Nd isotopes focuses on the clay size fraction of the sediment (< 2 µm) in order to minimize potential complexities related to granulometric processes and mineral sorting occurring during sediment transport and deposition, as described in Bastian et al.66. Thus, the variation in the clay-εNd signal coupled with sedimentation rate can be interpreted as Nile fluvial activity change. At the scale of the Holocene and the last deglaciation, Bastian et al.41 found that the highest εNd values recorded during the AHP, from ~ 14 to ~ 8 ka BP, indicate high Nile fluvial activity with larger proportions of particles derived from the Ethiopian Traps. Indeed, the radiogenic clay-εNd (~ -2) are closer to values observed in the Ethiopian Traps (εNd 0 to 7). In contrast, during LGM, sediments are characterized by lower εNd values (-8) and low sedimentation rate, indicating reduced Nile fluvial activity.

Data availability

The ice sheet data set, the ORCM output and the marine proxy data used in this study are made available in a Zenodo repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6496596). Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

Change history

18 January 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28159-1

References

Rossignol-Strick, M. African monsoons, an immediate climate response to orbital insolation. Nature 304, 46–49 (1983).

Rohling, E. J., Marino, G. & Grant, K. M. Mediterranean climate and oceanography, and the periodic development of anoxic events (sapropels). Earth Sci. Rev. 143, 62–97 (2015).

Grant, K. M. et al. The timing of Mediterranean sapropel deposition relative to insolation, sea-level and African monsoon changes. Quat. Sci. Rev. 140, 125–141 (2016).

Grimm, R. et al. Late glacial initiation of Holocene eastern Mediterranean sapropel formation. Nat. Commun. 6, 7099 (2015).

Soulet, G. et al. Black Sea “Lake” reservoir age evolution since the Last Glacial: Hydrologic and climatic implications. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 308, 245–258 (2011).

Soulet, G. et al. Abrupt drainage cycles of the Fennoscandian Ice Sheet. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 6682–6687 (2013).

Tudryn, A. et al. The Ponto-Caspian basin as a final trap for southeastern Scandinavian Ice-Sheet meltwater. Quat. Sci. Rev. 148, 29–43 (2016).

Yanchilina, A. G., Ryan, W. B. F., Kenna, T. C. & McManus, J. F. Meltwater floods into the Black and Caspian Seas during Heinrich Stadial 1. Earth Sci. Rev. 198, 102931 (2019).

Vidal, L. et al. Hydrology in the Sea of Marmara during the last 23 ka: Implications for timing of Black Sea connections and sapropel deposition. Paleoceanography 25, 1735 (2010).

Aloisi, G. et al. Freshening of the Marmara Sea prior to its post-glacial reconnection to the Mediterranean Sea. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 413, 176–185 (2015).

Aksu, A. E. & Hiscott, R. N. Persistent Holocene outflow from the Black Sea to the eastern Mediterranean Sea still contradicts the Noah’s Flood Hypothesis: A review of 1997–2021 evidence and a regional paleoceanographic synthesis for the latest Pleistocene-Holocene. Earth Sci. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EARSCIREV.2022.103960 (2022).

Sidorchuk, A. Y., Panin, A. V. & Borisova, O. K. Surface runoff to the Black Sea from the East European Plain during Last Glacial Maximum–Late Glacial time. in Geology and Geoarchaeology of the Black Sea Region: Beyond the Flood Hypothesis 473, 1–25 (Geological Society of America, 2011).

Chepalyga, A. L. The late glacial great flood in the Ponto-Caspian basin. in The Black Sea Flood Question: Changes in Coastline, Climate, and Human Settlement 119–148 (Springer, 2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5302-3_6.

Major, C., Ryan, W., Lericolais, G. & Hajdas, I. Constraints on Black Sea outflow to the Sea of Marmara during the last glacial–interglacial transition. Mar. Geol. 190, 19–34 (2002).

Herrle, J. O. et al. Black Sea outflow response to Holocene meltwater events. Sci. Rep. 8, 4081 (2018).

Huang, Y., Zheng, Y., Heng, P., Giosan, L. & Coolen, M. J. L. Black Sea paleosalinity evolution since the last deglaciation reconstructed from alkenone-inferred Isochrysidales diversity. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 564, 116881 (2021).

Bahr, A. et al. Abrupt changes of temperature and water chemistry in the late Pleistocene and early Holocene Black Sea. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 9, 1683 (2008).

Schmiedl, G. et al. Climatic forcing of eastern Mediterranean deep-water formation and benthic ecosystems during the past 22 000 years. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 3006–3020 (2010).

Ehrmann, W., Schmiedl, G., Hamann, Y. & Kuhnt, T. Distribution of clay minerals in surface sediments of the Aegean Sea: A compilation. Int. J. Earth Sci. 96, 769–780 (2007).

Kuhnt, T., Schmiedl, G., Ehrmann, W., Hamann, Y. & Hemleben, C. Deep-sea ecosystem variability of the Aegean Sea during the past 22 kyr as revealed by Benthic Foraminifera. Mar. Micropaleontol. 64, 141–162 (2007).

Kotthoff, U. et al. Climate dynamics in the borderlands of the Aegean Sea during formation of sapropel S1 deduced from a marine pollen record. Quat. Sci. Rev. 27, 832–845 (2008).

Lambeck, K., Sivan, D. & Purcell, A. Timing of the last Mediterranean Sea Black Sea connection from isostatic models and regional sea-level data. in The Black Sea Flood Question: Changes in Coastline, Climate, and Human Settlement 797–808 (Springer, 2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5302-3_33.

Badertscher, S. et al. Pleistocene water intrusions from the Mediterranean and Caspian seas into the Black Sea. Nat. Geosci. 4, 236–239 (2011).

Zubakov, V. A. Climatostratigraphic Scheme of the Black Sea Pleistocene and its Correlation with the Oxygen-Isotope Scale and Glacial Events. Quat. Res. 29, 1–24 (1988).

Patton, H. et al. Deglaciation of the Eurasian ice sheet complex. Quat. Sci. Rev. 169, 148–172 (2017).

Peltier, W. R., Argus, D. F. & Drummond, R. Space geodesy constrains ice age terminal deglaciation: The global ICE-6G_C (VM5a) model. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 120, 450–487 (2015).

Ivanovic, R. F. et al. Transient climate simulations of the deglaciation 21–9 thousand years before present (version 1): PMIP4 Core experiment design and boundary conditions. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 2563–2587 (2016).

Vadsaria, T., Li, L., Ramstein, G. & Dutay, J.-C. Development of a sequential tool, LMDZ-NEMO-med-V1, to conduct global-to-regional past climate simulation for the Mediterranean basin: An Early Holocene case study. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 2337–2354 (2020).

Lericolais, G., Bulois, C., Gillet, H. & Guichard, F. High frequency sea level fluctuations recorded in the Black Sea since the LGM. Glob. Planet. Change 66, 65–75 (2009).

Genov, I. The Black Sea level from the Last Glacial Maximum to the present time. Geol. Balc. 45, 3–19 (2016).

Georgievski, G. & Stanev, E. V. Paleo-evolution of the Black Sea watershed: Sea level and water transport through the Bosporus Straits as an indicator of the Lateglacial-Holocene transition. Clim. Dyn. 26, 631–644 (2006).

Stanev, E. V., Le Traon, P.-Y. & Peneva, E. L. Sea level variations and their dependency on meteorological and hydrological forcing: Analysis of altimeter and surface data for the Black Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 105, 17203–17216 (2000).

Revel, M. et al. 21,000 Years of Ethiopian African monsoon variability recorded in sediments of the western Nile deep-sea fan. Reg. Environ. Chang. 14, 1685–1696 (2014).

Ménot, G. et al. Timing and stepwise transitions of the African Humid Period from geochemical proxies in the Nile deep-sea fan sediments. Quat. Sci. Rev. 228, 106071 (2020).

Somot, S., Sevault, F., Déqué, M. & Crépon, M. 21st century climate change scenario for the Mediterranean using a coupled atmosphere–ocean regional climate model. Glob. Planet. Change 63, 112–126 (2007).

Macias, D. M., Garcia-Gorriz, E. & Stips, A. Productivity changes in the Mediterranean Sea for the twenty-first century in response to changes in the regional atmospheric forcing. Front. Mar. Sci. 2, 79 (2015).

Adloff, F. et al. Mediterranean Sea response to climate change in an ensemble of twenty first century scenarios. Clim. Dyn. 45, 2775–2802 (2015).

Fichaut, M. et al. MEDAR/MEDATLAS 2002: A Mediterranean and Black Sea database for operational oceanography. Clim. Dyn. 1, 645–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0422-9894(03)80107-1 (2003).

Houpert, L. et al. Seasonal cycle of the mixed layer, the seasonal thermocline and the upper-ocean heat storage rate in the Mediterranean Sea derived from observations. Prog. Oceanogr. 132, 333–352 (2015).

Revel, M. et al. 100,000 Years of African monsoon variability recorded in sediments of the Nile margin. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 1342–1362 (2010).

Bastian, L. et al. Co-variations of climate and silicate weathering in the Nile Basin during the Late Pleistocene. Quat. Sci. Rev. 264, 107012 (2021).

de Menocal, P. et al. Abrupt onset and termination of the African Humid Period. Quat. Sci. Rev. 19, 347–361 (2000).

Tierney, J. E., Pausata, F. S. R. & DeMenocal, P. B. Rainfall regimes of the Green Sahara. Sci. Adv. 3, e1601503 (2017).

Shanahan, T. M. et al. The time-transgressive termination of the African Humid Period. Nat. Geosci. 8, 140–144 (2015).

Vadsaria, T. et al. Simulating the Occurrence of the Last Sapropel Event (S1): Mediterranean Basin Ocean Dynamics Simulations Using Nd Isotopic Composition Modeling. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatology 34, 237–251 (2019).

Matthiesen, S. & Haines, K. A hydraulic box model study of the Mediterranean response to postglacial sea-level rise. Paleoceanography 18, 80 (2003).

Cornuault, M. et al. Deep water circulation within the eastern Mediterranean Sea over the last 95 kyr: New insights from stable isotopes and benthic foraminiferal assemblages. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 459, 1–14 (2016).

Obase, T. & Abe-Ouchi, A. Abrupt Bølling-Allerød warming simulated under gradual forcing of the last deglaciation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 11397–11405 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Transient simulation of last deglaciation with a new mechanism for Bølling-Allerød warming. Science 325, 310–314 (2009).

Beuvier, J. et al. Modeling the Mediterranean Sea interannual variability during 1961–2000: Focus on the Eastern Mediterranean Transient. J. Geophys. Res. 115, C08017 (2010).

Herrmann, M., Sevault, F., Beuvier, J. & Somot, S. What induced the exceptional 2005 convection event in the northwestern Mediterranean basin? Answers from a modeling study. J. Geophys. Res. 115, C12051 (2010).

Madec, G. NEMO ocean engine-version 3.0-Laboratoire d’Océanographie et du Climat: Expérimentation et Approches Numériques. (2008).

Dufresne, J.-L. et al. Climate change projections using the IPSL-CM5 Earth System Model: from CMIP3 to CMIP5. Clim. Dyn. 40, 2123–2165 (2013).

Ludwig, W., Dumont, E., Meybeck, M. & Heussner, S. River discharges of water and nutrients to the Mediterranean and Black Sea: Major drivers for ecosystem changes during past and future decades?. Prog. Oceanogr. 80, 199–217 (2009).

Siani, G., Magny, M., Paterne, M., Debret, M. & Fontugne, M. Paleohydrology reconstruction and Holocene climate variability in the South Adriatic Sea. Clim. Past 9, 499–515 (2013).

Sicre, M. A., Siani, G., Genty, D., Kallel, N. & Essallami, L. Seemingly divergent sea surface temperature proxy records in the central Mediterranean during the last deglaciation. Clim. Past 9, 1375–1383 (2013).

Cornuault, M. et al. Circulation changes in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea over the past 23,000 years inferred from authigenic nd isotopic ratios. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 33, 264–280 (2018).

Kallel, N. et al. Mediterranean pluvial periods and sapropel formation over the last 200 000 years. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 157, 45–58 (2000).

Duplessy, J.-C. et al. Surface salinity reconstruction of the north-atlantic ocean during the last glacial maximum. Oceanol. Acta 14, 311–324 (1991).

Shackleton, N. J. Attainment of isotopic equilibrium between ocean water and the benthonic foraminifera genus Uvigerina: Isotopic changes in the ocean during the last glacial. (1974).

Lambeck, K., Rouby, H., Purcell, A., Sun, Y. & Sambridge, M. Sea level and global ice volumes from the Last Glacial Maximum to the Holocene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 15296–15303 (2014).

Lambeck, K. & Purcell, A. Sea-level change in the Mediterranean Sea since the LGM: Model predictions for tectonically stable areas. Quat. Sci. Rev. 24, 1969–1988 (2005).

Duplessy, J. C., Labeyrie, L. & Waelbroeck, C. Constraints on the ocean oxygen isotopic enrichment between the Last Glacial Maximum and the Holocene: Paleoceanographic implications. Quat. Sci. Rev. 21, 315–330 (2002).

Kallel, N., Paterne, M., Labeyrie, L., Duplessy, J.-C. & Arnold, M. Temperature and salinity records of the Tyrrhenian Sea during the last 18,000 years. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 135, 97–108 (1997).

Bayon, G. et al. Rare earth elements and neodymium isotopes in world river sediments revisited. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 170, 17–38 (2015).

Bastian, L., Revel, M., Bayon, G., Dufour, A. & Vigier, N. Abrupt response of chemical weathering to Late Quaternary hydroclimate changes in northeast Africa. Sci. Rep. 7, 44231 (2017).

Ehlers, J. & Gibbard, P. L. Quaternary Glaciations: Extent and Chronology: Part I: Europe Band 2 von Developments in Quaternary Science. 488 (2004).

Grosswald, M. G. Late Weichselian ice sheet of Northern Eurasia. Quaternary Res. 13(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/0033-5894(80)90080-0 (1980).

Komatsu, G. et al. Catastrophic flooding, palaeolakes, and late Quaternary drainage reorganization in northern Eurasia. Int. Geol. Rev. 58(14), 1693–1722. https://doi.org/10.1080/00206814.2015.1048314 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Henry Patton for sharing the data relative to the FIS reconstruction and Ivan Genov and Ali Aksu for their respective BSL reconstructions. We also thank Carlo Mologni for sharing the data relative to the MS27PT sediment core. We also thank Kazuyo Tachikawa, Laurence Vidal, Eelco Rohling and Uwe Mikolajewicz for the fruitful discussion preceding the long submission process of this article. We thank Mary Minnock for her professional English editing. For the purposes of this work, access was granted to the HPC (High Performance Computing) resources of TGCC (Très Grand Centre de Calcul) under the allocations 2017-A0010102212, 2018-A0030102212 and 2018-A004-01-00239 made by GENCI (Grand Équipement National de Calcul Intensif). This research was supported by the French National Program LEFE (Les Envelopes Fluides et l’Environnement) “HoMoSapIENS” and the French National Research Agency (ANR) project MEDSENS (ANR-19-CE01-0019). Tristan Vadsaria, the first author, was supported by JSPS (Japan Society for the Promotion of Science) KAKENHI (Grant Number 17H06104).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was codesigned and approved by all coauthors. The simulation protocol was constructed by T.V. and S.Z. from a modeling architecture provided by L.L. T.V. conducted the numerical simulations and drafted the first version of the manuscript. G.S. provided new data of the marine core MD90-917 for the time interval 20–12 ka and calculated the δ18Ow. M.R. provided data of the marine core MS27PT and helped to interpret the data. T.O. and A.A.B. provided MIROC4m last deglaciation model output and helped with the analysis. All coauthors are closely involved in the writing and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors. The authors omitted the References 68 and 69. In addition, the article contained an error in the legend of figure 2. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction notice for this Article.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vadsaria, T., Zaragosi, S., Ramstein, G. et al. Freshwater influx to the Eastern Mediterranean Sea from the melting of the Fennoscandian ice sheet during the last deglaciation. Sci Rep 12, 8466 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12055-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12055-1

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.