Abstract

Defences of hosts against brood parasitic cuckoos include detection and ejection of cuckoo eggs from the nest. Ejection behaviour often involves puncturing the cuckoo egg, which is predicted to drive the evolution of thicker eggshells in cuckoos that parasitise such hosts. Here we test this prediction in four Australian cuckoo species and their hosts, using Hall-effect magnetic-inference to directly estimate eggshell thickness in parasitised clutches. In Australia, hosts that build cup-shaped nests are generally adept at ejecting cuckoo eggs, whereas hosts that build dome-shaped nests mostly accept foreign eggs. We analysed two datasets: a small sample of hosts with known egg ejection rates and a broader sample of hosts where egg ejection behaviour was inferred based on nest type (dome or cup). Contrary to predictions, cuckoos that exploit dome-nesting hosts (acceptor hosts) had significantly thicker eggshells relative to their hosts than cuckoos that exploit cup-nesting hosts (ejector hosts). No difference in eggshell thicknesses was observed in the smaller sample of hosts with known egg ejection rates, probably due to lack of power. Overall cuckoo eggshell thickness did not deviate from the expected avian relationship between eggshell thickness and egg length estimated from 74 bird species. Our results do not support the hypothesis that thicker eggshells have evolved in response to host ejection behaviour in Australian cuckoos, but are consistent with the hypothesis that thicker eggshells have evolved to reduce the risk of breakage when eggs are dropped into dome nests.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Avian obligate brood parasites, such as cuckoos, minimise their reproductive costs by laying their eggs in the nests of other birds to be raised by the host. As resources are diverted away from the host’s own young, pressure is placed on hosts to evade parasitism, which in turn places pressure on parasites to evolve ever more elaborate tactics to evade detection by hosts. This results in a ‘co-evolutionary arms race’1.

Brood parasitism imposes heavy costs on hosts. Cuckoo nestlings usually evict or outcompete host nestlings, so hosts typically fail to fledge any of their own young, and thus selection favours the evolution of host defences. Host defences include mobbing of adult cuckoos2, and rejection of cuckoo eggs3,4 or chicks5,6,7. Host defences have, in turn, selected for a suite of adaptations in brood parasites that facilitate parasitism of host nests, including rapid egg laying8, and mimicry of host eggs3 or chicks9,10. Specifically, some brood parasites have evolved mimicry of host egg shape and colour11,12, chick begging calls13,14 and chick morphology (e.g. skin colour, mouth and gape patterns9,10, as well as adult mimicry of non-parasitic birds15,16,17,18,19,20. An alternative strategy employed by other brood parasites is to lay dark eggs that are cryptic rather than mimetic when the nest is dome-shaped, causing the egg to blend into the dimly lit interior of the nest, thereby escaping detection by the host15,21,22. The interactions between brood parasites and their hosts provide some of the most well-studied examples of co-evolutionary arms races in nature1.

Although previous studies have demonstrated cases where traits expressed by brood parasites (such as egg colour, size and pattern mimicry) have arisen due to co-evolution with the host, it is unclear whether other phenotypes are the outcome of co-evolution or other processes. For example, the eggshells of many cuckoo species are thicker and stronger than those of their hosts, relative to body size23,24,25,26, but there is conflicting evidence about whether eggshell thickness has evolved through co-evolution with hosts. Eggshell thickness is a physiologically constrained trait. The eggshell must be simultaneously thick enough to avoid breakage and mediate UV exposure during embryonic development, and yet sufficiently thin for efficient embryonic gas exchange and to allow the chick to hatch27,28,29,30. Thus, it is an interesting case study of how co-evolutionary pressures operate in the presence of tight physiological constraints.

The evolution of thicker eggshells is predicted to be an effective counter strategy to host defence behaviour because the cuckoo eggs are more difficult for the host to puncture, which impedes the host’s ability to remove the egg. This is called the ‘puncture resistance hypothesis’24,31. There are also additional theories that predict the evolution of thicker eggshells in cuckoos that are unrelated to host egg ejection behaviour. For example, the ‘impact resistance hypothesis’23 predicts that cuckoo chick survival is increased by reducing the damage sustained during rapid egg laying events or when the egg is laid from a height above the nest32. The ‘heat retention hypothesis’33 predicts that cuckoo chick survival is increased by accelerated developmental rates allowing early hatching and eviction of the host’s eggs34,35. Finally, the ‘multiple parasitism’ hypothesis predicts that a thicker eggshell protects cuckoo eggs from being damaged by other cuckoos in repeatedly parasitised nests26. Thus, there is a general expectation that selection favours the evolution of thicker eggshells in brood parasites.

The experimental evidence regarding the evolution in brood parasites is somewhat conflicting. An early study compared the eggshell thickness of Cuculus/Cacomantis/Chalcites/Chrysococcyx genera of cuckoos with those of Clamator cuckoos and found that the eggshell thickness of the former group did not differ significantly from those of their hosts, whereas the latter group had significantly thicker eggshells than their hosts26. However, a more in-depth study of Cuculus canorus and its hosts revealed that races that exploit hosts with strong egg ejection behaviour have thicker shells relative to their hosts than races that exploit less discriminating species36. This suggests that cuckoos within Cuculus/Cacomantis/Chalcites/Chrysococcyx cuckoos included in the Brooker & Brooker (1991)26 study may differ in their eggshell thickness according to the ejection behaviour of their hosts.

Here we investigate whether co-evolutionary interactions with hosts drive the evolution of eggshell thickness in brood parasites, by studying a range of host species that vary in their egg ejection behaviour. We predict that if thicker eggshells evolve to reduce the risk of egg ejection by hosts, cuckoo eggshells should be thicker than those of their hosts only in cuckoo species that exploit egg-ejecting hosts. Conversely, if thicker eggshells have evolved to reduce the risk of breakage, eggshell thickness—while still being thicker relative to their host—should not differ between cuckoos that exploit egg-ejecting versus egg accepting hosts.

Results

There was a high degree of repeatability between independent thickness measurements in 10 eggs that were measured multiple times. The mean apex average measure intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) was 0.961 with a 95% confidence interval from 0.912 to 0.989 (F9,90 = 25.6, P < 0.0001). The mean meridian average measure ICC was 0.961 with a 95% confidence interval from 0.913 to 0.989 (F9,90 = 25.9, P < 0.0001) (Supplementary Information Sect. 4.0).

Overall, the thickness of cuckoo eggshells relative to their length was not significantly different from that of their hosts (Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test, Apex: S = 91, N = 47, P = 0.34; Meridian: S = -114, N = 59, P = 0.39). Moreover, for hosts with known egg ejection rates, there was no significant difference in the relative thickness of cuckoo:host eggshells between cuckoos that exploit ejector hosts and those that exploit acceptors (Figs. 1 and 2) at the apex of the egg (F1,1.98 = 2.31, P = 0.27) or at the meridian of the egg (F1,5.6 = 0.99, P = 0.36). However, when considering hosts with both known and unknown egg ejection rates, cuckoos that exploit dome-nesting acceptors showed a significant tendency to have thicker eggshells relative to their hosts than cuckoos that exploit cup-nesting ejectors, at both the apex (F1,12.47 = 7.72, P = 0.02) and the meridian of the egg (F1,14.32 = 8.86, P = 0.01) (Figs. 1 and 2).

The ratio of normalised eggshell thickness between cuckoos and their ejector versus acceptor hosts. (A) In the smaller sample size dataset that includes only hosts with known egg ejection rates, there is no significant difference in the cuckoo:host ratio of eggshell thickness between acceptors and ejectors at either point measured (apex: F1,1.98 = 2.31, P = 0.27; meridian: F1,5.6 = 0.99, P = 0.36). (B) When all hosts are considered and ejection behaviour is inferred from nest type, cuckoos that exploit acceptor hosts have thicker eggshells relative to their hosts than cuckoos that exploit ejectors, at both the apex (F1,12.47 = 7.72, P = 0.02) and the meridian of the egg (F1,14.32 = 8.86, P = 0.01).

Eggshell thickness of cuckoos (orange) and their hosts (blue). Eggshell thickness was measured at two points on the egg: (A) the meridian of the egg, which is the circumference around the widest part of the egg and (B) the apex of the egg, which is the most conical end opposite the air sac. Eggshell thickness was normalised for interspecies comparisons by dividing the mean eggshell thickness of each egg by its length. The total eggshell thickness distribution is shown as black dots (Supplementary data file 1). Box plots are the median, interquartile range (Q1–Q3) and range (min–max). Raw data prior to normalisation are displayed in Fig. S3.

As expected, there was a significant positive relationship between egg length and eggshell thickness in the 74 avian species examined (Fig. 3). The results of the phylogenetically corrected and uncorrected linear regression analyses are qualitatively identical and the strength of the association between eggshell size and thickness is comparable. Before correcting for phylogenetic relatedness, egg length predicted meridian eggshell thickness slightly better than apex eggshell thickness (Linear regression meridian: y = 7.4636x−48.406; R2 = 0.7822; P < 0.0001. Linear regression apex: y = 7.5163x−60.578; R2 = 0.6768; P < 0.0001). There was a slightly higher sample size in the meridian data set (N = 73 avian species + 4 cuckoos) compared to the apex data set (N = 59 avian species + 4 cuckoos). Sample sizes differed between apex and meridian estimates because some measurements were not possible due to eggshell damage or blow hole placement. The four species of brood parasitic cuckoos adhered to the general avian relationship between egg length and eggshell thickness, occurring within the 95% confidence interval for all other species (Fig. 3). The residuals (phylogenetic and non-phylogenetic) were not distinct from those of other species, and cuckoos did not have particularly thick eggshells compared to other species (Figs. S5 and S6).

Eggshell thickness as a function of egg length in avian species. Eggshell thickness was measured at two points on the egg: (A) the meridian of the egg, which is the circumference around the widest part of the egg (N = 73) and (B) the apex of the egg, which is the most conical end opposite the air sac (N = 59). Linear regression was conducted on species that do not employ a brood parasitic reproductive strategy (circles). Brood parasitic cuckoos were plotted separately (filled black markers). Cuckoo species that parasitise acceptor hosts without egg ejection (black triangles) and cuckoo species that exploit egg-ejecting hosts (black diamonds) fell within the 95% confidence limit (grey shaded area) predicted for non-parasitic species. Figures of residuals when using phylogenetic correction are presented in supplementary material (Figs. S5 and S6).

Discussion

We set out to determine if eggshell thickness in Australian avian brood parasites has evolved in response to cuckoo-host co-evolutionary interactions. Specifically, we predicted that cuckoos that exploit ejector hosts should display thicker eggshells relative to their hosts than cuckoos that exploit acceptor hosts, and thicker eggshells than predicted for their size23,24,25. Overall, we found that cuckoo eggshell thickness did not differ significantly either from host eggshell thickness or from the avian average for a given egg size. Similarly, when considering hosts with known egg ejection rates only, the eggshell thickness of cuckoos that exploit ejector hosts did not differ significantly from the eggshell thickness of cuckoos that exploit acceptor hosts. Previous research has shown that dome-nesting hosts tend to accept cuckoo eggs, whereas cup-nesting hosts tend to eject cuckoo eggs37. Therefore, we also investigated eggshell thickness in a larger sample of cuckoo hosts, for whom egg ejection rates were unknown but inferred based on nest type. Contrary to predictions, cuckoos that exploit dome-nesting hosts had significantly thicker eggshells relative to their hosts than cuckoos that exploit cup-nesting hosts.

In contrast to European and African cuckoos24,31, our data from Australian cuckoos does not support the hypothesis that thicker eggshells evolve in response to host egg ejection behaviour. A possible explanation for this is that ejector hosts may have adopted defence strategies that do not select for increased eggshell thickness in cuckoos. The host defence that is believed to select for thicker cuckoo eggshells is puncture ejection 31. However, there may be little selection for thicker cuckoo eggshells if hosts use grasp ejection (grasping the whole, undamaged egg in the mandible) rather than puncture ejection38. Grasp ejection is thought to be particularly constrained among hosts that have small mandibles24. While, the method of ejection is unknown for most Australian cuckoo hosts, it is interesting to note that the ejector hosts in our study were the larger-bodied species among the hosts and are therefore likely to be more capable of grasp-ejecting foreign eggs than the acceptor hosts.

Our finding that cuckoos that exploit dome-nesting hosts had significantly thicker eggshells relative to their hosts than cuckoos that exploit cup-nesting hosts is consistent with the hypothesis that thicker eggshells evolve in brood parasites to prevent breakage during egg laying. All acceptor hosts in this analysis build dome-shaped nests. Cuckoos that exploit these dome nesting hosts do not fully enter the nest, but leave the lower back, wingtips and tail outside the nest entrance during egg laying39, suggesting that the egg is dropped down from the nest entrance into the bowl of the nest. Thus, we might expect that these cuckoos would be under selection for thicker eggshells to avoid breakage during laying23.

Another possibility that remains to be tested, is whether embryonic behaviour can impact selective pressures on eggshells. For example, in European cuckoos, brood parasite embryos are stronger and exercise more whilst inside the egg40. Increased embryonic activity could conceivably result in selection for thicker eggshells in cuckoo species if thicker shells are associated with increased hatching success. However, nest architecture would need to be a strong predictor of embryonic activity to fully explain our observations that thicker relative eggshells only occur in dome-nesting species.

We did not find a significant difference in eggshell thickness relative to hosts between cuckoos that exploit acceptor and ejector hosts when considering hosts with known egg ejection rates only, although the non-significant trend was in the same direction as for the analysis considering hosts with both known and unknown egg ejection rates. This is likely to reflect insufficient power due to the small number of host species whose egg ejection rates have been quantified. However, this result is consistent with an earlier study that also found no difference in eggshell thickness of the Cuculus/Cacomantis/Chalcites/Chrysococcyx group of cuckoos and their hosts26. In Australian cuckoos, other factors could also be influential determinants of eggshell thickness, such as: diet, maternal age, habitat-dependent calcium availability41, chemical pollutants42,43,44,45 or the developmental environment46. Alternatively, egg strength may be enhanced through mechanisms other than thicker eggshells, such as denser shells47, or a stronger microstructure within the shell48,49. These possibilities remain to be tested for Australian cuckoo species.

We need to consider aspects of avian biology and our sampling strategy that may have impaired the power of our study to detect differences in eggshell thickness. Eggshell thickness is a physiologically constrained trait that must be maintained within the thresholds that allow embryo development. Thus, it is possible that there is insufficient variation in the phenotype for evolution to act effectively upon. However, we suggest that this is not the case due to the wealth of other studies that have demonstrated evidence for the evolution of eggshell thickness in avian and non-avian egg laying species50,51,52. Another point to consider is whether the co-evolutionary interactions between hosts and cuckoos in our study are sufficiently strong to select for changes to eggshell thickness. In the case of the bronze-cuckoos and their hosts in this analysis, the co-evolutionary relationship is very strong. The cuckoos specialise on their hosts and show highly specialised adaptations to their hosts, such as mimicry of host nestling skin colour and begging calls9,13. Similarly, the hosts show highly specialised adaptations to prevent cuckoo parasitism, such as a special alarm call that is only produced in the presence of cuckoos9, rejection of cuckoo chicks5 and early breeding to avoid parasitism53. The pallid cuckoo has been under sufficiently strong selection from egg rejection by hosts to have evolved several different races, each of which exploits a different host and lays an egg that mimics that of its preferred host54. Similarly, the koel has evolved eggs that closely mimic the appearance of those of one of its major hosts55. Thus, it seems likely that the co-evolutionary interactions between these cuckoos and their hosts have been sufficiently strong and long lasting to allow for selection on eggshell strength.

We studied eggshell thickness in more than a single host for all cuckoo-host comparisons. This means that the variation in eggshell thickness, even when normalised for egg size, is much larger among the host data than the cuckoo data. We could improve power by comparing eggshell thickness in only the most heavily exploited host species to the associated cuckoo species. This was unfortunately not possible in this study and would require nation-wide co-ordination of eggshell specimens to have a sufficient sample size for statistical comparisons. Additionally, if egg ejection rates were known for hosts of more Australian cuckoo species, this would improve power to test the puncture resistance hypothesis by comparing more than two cuckoo species for each type of host ejection behaviour (accept or eject). Ideally, investigating cuckoos that are phylogenetically distant to the current study species would improve confidence in our conclusions.

Our study is the first to apply Hall-effect magnetic-inference methodology to estimate eggshell thickness in museum eggshells without damage. We have shown that the non-destructive method is highly repeatable and provides direct and near continuous estimates of eggshell thickness at any point in the egg. This approach is an improvement upon previous methodologies that indirectly estimate eggshell thickness56,57 or use analog micrometers to measure thickness at a single location on the egg58,59. Importantly, Hall-effect magnetic-inference methodology is very transportable and allows measurements to be taken in the field or in situ at museums when specimens cannot be transported. It is less expensive and more accessible than scanning electron microscopy60 and micro computed tomography61,62, and complements other non-invasive approaches to estimate eggshell thickness in vivo63,64. Similar to previous benchmarking studies65, direct comparison of the precision and accuracy of all eggshell thickness estimation methods would be a valuable resource for the research community. By combining new digital technologies with the depth of historical collecting effort, our study has rapidly generated a large dataset suitable for comparative analyses (78 avian species; 34 families; 12 orders). Hall-effect magnetic-inference could facilitate researchers to take full advantage of the estimated 5 million egg specimens in collections world-wide66 and accelerate morphological, physiological, ecotoxicological, developmental and evolutionary research that relies upon accurate estimation of eggshell thickness traits.

Our results provide some support for the ‘impact resistance hypothesis’23, but further work is warranted. In particular, more data is needed on cuckoo-host biology, including rates of egg ejection and methods of egg ejection in the hosts of other species of cuckoos. Analysis of cuckoo eggshell structure and density may also be informative. Our study is likely to be underpowered due to inflated variation in host estimates and because we were restricted to studying only two cuckoo species for each type of host response to cuckoo eggs. Investigation of eggshell thickness restricting hosts to the most heavily exploited primary host and the addition of more Australian cuckoo-host pairs may add power to the trends observed here. This additional work will contribute to a greater understanding of the capacity for co-evolutionary pressures to drive phenotypic divergence.

Methods

Cuckoo and host species

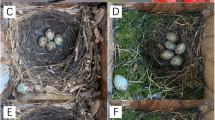

The parasitic cuckoo species selected for use in this study were chosen based on previous knowledge of their host selection and the egg ejection behaviour of those hosts15,37,67,68,69,70,71. We selected four Australian cuckoo species based on the known egg ejection rates of their primary hosts from our earlier studies. Two congeneric species, Horsfield’s bronze-cuckoos Chalcites basalis and shining bronze-cuckoos C. lucidus, exploit hosts that build dome-shaped nests in which detection of foreign eggs is constrained by poor visibility in the dark interior22,37. Hosts of these two cuckoo species rarely eject either naturally-laid cuckoo eggs, or experimental, non-mimetic plastic model eggs, of similar size to their own (Table 1)5,13,37. The two other cuckoo species in the study, the pallid cuckoo (Cuculus pallidus) and the Pacific koel (Eudynamis orientalis), exploit hosts that build cup-shaped nests with good visibility, and these hosts routinely eject both naturally-laid cuckoo eggs and experimental, non-mimetic model eggs (Table 1)37,72,73.

In addition to their primary hosts included in this analysis, these cuckoos also exploit several secondary hosts whose egg ejection behaviour is unknown67. However, previous analyses indicate that there is a strong association between visibility inside the nest and egg ejection behaviour; hosts that build dome-shaped nests tend to accept foreign eggs (100% of Australian hosts [N = 6] ejected ≤ 25% of foreign eggs37), whereas hosts that build cup-shaped nests tend to eject foreign eggs (75% of hosts ejected > 25% of foreign eggs, [N = 8]37). Therefore, we conducted a second set of analyses that included both primary and secondary hosts of these cuckoos (Table 1), where egg ejection behaviour was inferred based on nest type for the secondary hosts.

Eggshell measurements

All eggshells used in this study were sourced from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) Australian National Wildlife Collection (ANWC) oology research collection (Supplementary data file 1). All eggs had been prepared at the time of collection by drilling a small hole in the shell, through which the egg contents were blown and removed. The eggshells were then washed and stored dry. Collector’s notes and consistently small blow-hole diameters indicate that eggs were sampled early in development and were unlikely to be subject to significant eggshell thinning during development (Supplementary data file 1). The availability of parasitised clutches in the ANWC collection dictated which host species were included and the sample size for this study (Table 1; Supplementary data file 1). Suitable cuckoo-host clutches contained at least one intact host and one cuckoo egg, both identified to the species level.

We used a precision industrial wall-thickness measuring tool to directly measure eggshell thickness via Hall-effect magnetic-inference, in a similar approach to Peterson et al.75. However, unlike this previous study we did not cut or damage the eggshell to take measurements. Specifically, we used the ElectroPhysik MiniTest FH7200 gauge and FH4 magnetic probe, with a 1.5 mm diameter steel ball which was inserted inside the empty eggshell, through the existing blow-hole in the specimen (SI 2.0). Thus, all eggs included in the study necessarily had a blowhole diameter > 1.5 mm. This probe and steel ball combination measures thicknesses up to 2 mm, with an accuracy of ± 3 µm + 1% of the reading (Check Line®, Germany). Thickness data was collected at a rate of 10 measurements per second. We did not place the steel probe in direct contact with the egg. Instead, we inserted a 0.73 mm sheet of plastic (cellulose acetate) in between the probe and the egg to minimise risk of damage (hereafter referred to as the ‘protector’).

Eggshell thickness data was collected at two regions on each egg—the apex (the most conical end opposite the air sac) and the meridian (the circumference around the widest part of the egg). Manual handling of the egg specimens during thickness estimation is described in detail in Supplementary Information Sect. 2.0 and Fig. S1. Briefly, we inserted the steel ball though the blow hole and rolled the ball to the apex of the egg. We always approached the magnetic probe (and protector) apex-first because this is the strongest part of the egg. Apex thickness was recorded for five seconds by leaving the egg stationary and untouched on the probe (Fig. S1; Video Supplement 1). We then rolled the ball until it was positioned adjacent to the side blow-hole and rotated the egg slowly, to record the meridian thickness (Fig. S1; Video Supplement 2). The steel ball was removed by rolling it back through the blow-hole, whilst still in contact with the probe (Video Supplement 3). Preliminary method optimisation using 60 unregistered eggs indicated that the risk of breaking an egg during this manual handling was very low if specimens had no pre-existing physical damage (cracks, chips, hairline fractures determined via illuminating the egg with a cold-light source) and weighed > 0.05 g (Fig. S2). No registered collection items sustained damage in this study.

All data were inspected and exported following the manufacturer’s protocols in the software package MSoft 7 Basic (Check Line®, Germany). The protector thickness was subtracted from the raw gauge readings to obtain a measurement of eggshell thickness (SI 2.0). Mean thickness (µm) was calculated for both apex and meridian measurements of each egg after removing outliers (classified as data points lying outside 1.5X the interquartile range). Mass (g), length (mm) and breadth (mm) were also measured for each egg. Length and breadth measurements were calculated from a 2D photograph of each egg, following Attard et al.76. Mass was measured using an electronic balance to the nearest 0.001 g (CT-250 On Balance Digital Scale).

Repeatability Analysis

The repeatability of our Hall-effect magnetic-inference methodology with the ElectroPhysik probe was investigated by conducting replicate thickness measurements (N = 10) for an additional 10 unregistered eggs. Repeatability was calculated using the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC), in the R package irr (SI 4.0). Significance was determined where p < 0.05.

Comparative analysis of avian and cuckoo eggshell thickness

Previous studies indicate that eggshell thickness is positively correlated with egg size; larger eggs have thicker shells77. To investigate whether cuckoo eggshell thickness deviates from this general relationship, we calculated the mean eggshell thickness in a total of 78 species, comprising 12 avian orders and 34 families (total N = 3134 eggs) (Table 2). Our analysis included previously published data for 12 species75. We used a phylogenetic generalised least squares regression (PGLS) in the R package caper78, and estimated the relationship between eggshell length and two measures of thickness (apex and meridian). To control for phylogenetic relatedness, we used a maximum clade credibility (MCC) tree based on 100 trees downloaded from birdtree.org79. The MCC tree, which is the tree with the maximum product of the posterior clade probabilities, was obtained using the R package phangorn80. We extracted both phylogenetic residuals (phylogenetically independent) and residuals obtained from the phylogenetic regression line, and visually evaluated whether these residuals from cuckoo species were extreme values (e.g., were greater than expected by their size and phylogenetic position). We also used a linear regression of egg length versus mean eggshell thickness for 74 non-brood parasitic avian using the package lm in R v. 3.6.081. Cuckoos were not included in this linear regression analysis and were plotted separately. We tested whether cuckoo values fell within the 95% confidence intervals of this regression.

Statistical analysis

The distribution of raw and normalised eggshell thickness in cuckoos and their hosts was plotted and visually inspected in ggplot2 (Figs. S3 and Fig. 2). Within a species, outliers in the distribution of mean thicknesses (as defined as above) were removed. To account for inter-specific differences in egg size (which is correlated with eggshell thickness) ‘normalised thickness’ was calculated for each sample by dividing the eggshell thickness by egg length75. This approach is expected to successfully normalise the data because egg length explains a large proportion of the inter-species variation in eggshell thickness (Fig. 3). We tested for successful normalisation by regressing normalised eggshell thickness against eggshell mass (Fig. S4).

We tested whether, overall, the thickness of cuckoo eggshells relative to their length differed from that of their hosts at both the apex and the meridian of the egg using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test on matched pairs of cuckoo and host eggs. For this analysis, any unpaired egg samples, or samples with data missing for either the host or cuckoo of the pair were removed from analysis. Final sample sizes for each treatment can be found in Fig. 1. We then tested whether host ejection behaviour predicted the ratio of cuckoo to host normalised eggshell thickness. We used a Restricted Maximum Likelihood Model (REML), with cuckoo:host normalised eggshell thickness ratio as the response variable, host response to foreign eggs (accept or eject) as the fixed effect and host species nested within cuckoo species as the random effect. For all models we checked standardised residuals for normality. Log10 transformation of variables improved the normality of residuals (Anderson Darling Tests for Goodness-of-fit, all P > 0.4), so we present these results, although the qualitative results remained unchanged regardless of whether or not data were transformed. We ran four models; (1) eggshell thickness at the meridian including only hosts with known egg ejection rates, (2) eggshell thickness at the meridian including hosts with both known and unknown egg ejection rates, (3) eggshell thickness at the apex including only hosts with known egg ejection rates, and (4) eggshell thickness at the apex including hosts with both known and unknown egg ejection rates. The analyses were run in JMP v.15 (SAS Institute Inc, 2019).

Data availability

Raw data can be accessed through DataDryad. Correspondence and requests for material should be addressed to CEH (clare.holleley@csiro.au) or NEL (naomi.langmore@anu.edu.au).

References

Rothstein, S. I. A model system for coevolution: Avian brood parasitism. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 21, 481–508 (1990).

Feeney, W. E. et al. Brood parasitism and the evolution of cooperative breeding in birds. Science 342, 1506–1508 (2013).

Brooke, M. de L. & Davies, N. B. Egg mimicry by cuckoos Cuculus canorus in relation to discrimination by hosts. Nature 335, 630–632 (1988).

Medina, I. & Langmore, N. E. The costs of avian brood parasitism explain variation in egg rejection behaviour in hosts. Biol. Let. 11, 20150296 (2015).

Langmore, N. E., Hunt, S. & Kilner, R. M. Escalation of a coevolutionary arms race through host rejection of brood parasitic young. Nature 422, 157–160 (2003).

Grim, T. Experimental evidence for chick discrimination without recognition in a brood parasite host. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 274, 373–381 (2007).

Sato, N. J., Tokue, K., Noske, R. A., Mikami, O. K. & Ueda, K. Evicting cuckoo nestlings from the nest: A new anti-parasitism behaviour. Biol. Let. 6, 67–69. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2009.0540 (2010).

Davies, N. & Brooke, M. de L. Cuckoos versus reed warblers: Adaptations and counteradaptations. Anim. Behav. 36, 262–284 (1988).

Langmore, N. E. et al. Visual mimicry of host nestlings by cuckoos. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 278, 2455–2463 (2011).

Noh, H.-J., Gloag, R. & Langmore, N. E. True recognition of nestlings by hosts selects for mimetic cuckoo chicks. Proc. R. Soc. B: Bio. Sci. 285, 20180726 (2018).

Spottiswoode, C. N. & Stevens, M. Host-parasite arms races and rapid changes in bird egg appearance. Am. Nat. 179, 633–648. https://doi.org/10.1086/665031 (2012).

Taylor, C. J. & Langmore, N. E. How do brood-parasitic cuckoos reconcile conflicting environmental and host selection pressures on egg size investment?. Anim. Behav. 168, 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2020.08.003 (2020).

Langmore, N. E., Maurer, G., Adcock, G. J. & Kilner, R. M. Socially acquired host-specific mimicry and the evolution of host races in Horsfield’s bronze-cuckoo Chalcites basalis. Evolution 62, 1689–1699 (2008).

Noh, H. J., Jacomb, F., Gloag, R. & Langmore, N. E. Frontline defences against cuckoo parasitism in the large-billed gerygones. Anim. Behav. 174, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2021.01.021 (2021).

Langmore, N. E. & Kilner, R. M. Why do Horsfield’s bronze-cuckoo Chalcites basalis eggs mimic those of their hosts?. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 63, 1127–1131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-009-0759-9 (2009).

Spottiswoode, C. N. & Stevens, M. How to evade a coevolving brood parasite: Egg discrimination versus egg variability as host defences. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 278, 3566–3573. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2011.0401 (2011).

Yang, C., Wang, L., Liang, W. & Møller, A. P. Egg recognition as antiparasitism defence in hosts does not select for laying of matching eggs in parasitic cuckoos. Anim. Behav. 122, 177–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2016.10.018 (2016).

Stevens, M. Bird brood parasitism. Curr. Biol. 23, R909–R913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2013.08.025 (2013).

Feeney, W. E., Troscianko, J., Langmore, N. E. & Spottiswoode, C. N. Evidence for aggressive mimicry in an adult brood parasitic bird, and generalized defences in its host. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 282, 20150795 (2015).

Davies, N. B. & Welbergen, J. A. Cuckoo–hawk mimicry? An experimental test. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 275, 1817–1822 (2008).

Brooker, L. C. & Brooker, M. G. Why are cuckoos host specific?. Oikos 57, 301–309. https://doi.org/10.2307/3565958 (1990).

Langmore, N. E., Stevens, M., Maurer, G. & Kilner, R. M. Are dark cuckoo eggs cryptic in host nests?. Anim. Behav. 78, 461–468 (2009).

Lack, D. L. Ecological Adaptations for Breeding in Birds (Methuen & Co., Ltd., 1968).

Spaw, C. D. & Rohwer, S. A comparative study of eggshell thickness in cowbirds and other passerines. The Condor 89, 307–318. https://doi.org/10.2307/1368483 (1987).

Igic, B. et al. Alternative mechanisms of increased eggshell hardness of avian brood parasites relative to host species. J. R. Soc. Interface 8, 1654–1664. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2011.0207 (2011).

Brooker, M. G. & Brooker, L. C. Eggshell strength in cuckoos and cowbirds. Ibis 133, 406–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919X.1991.tb04589.x (1991).

Maurer, G. et al. First light for avian embryos: eggshell thickness and pigmentation mediate variation in development and UV exposure in wild bird eggs. Funct. Ecol. 29, 209–218 (2015).

Amos, A. & Rahn, H. Pores in avian eggshells: Gas conductance, gas exchange and embryonic growth rate. Respir. Physiol. 61, 1–20 (1985).

Ar, A., Rahn, H. & Paganelli, C. V. The avian egg: Mass and strength. Condor 81, 331–337 (1979).

Rahn, H. & Ar, A. Gas-exchange of the avian egg: Time, structure, and function. Am. Zool. 20, 477–484 (1980).

Swynnerton, C. Rejections by birds of eggs unlike their own: With remarks on some of the cuckoo problems. Ibis 60, 127–154 (1918).

López, A. V., Fiorini, V. D., Ellison, K. & Peer, B. D. Thick eggshells of brood parasitic cowbirds protect their eggs and damage host eggs during laying. Behav. Ecol. 29, 965–973 (2018).

Wyllie, I. The Cuckoo (Batsford, 1981).

Yang, C. et al. Keeping eggs warm: Thermal and developmental advantages for parasitic cuckoos of laying unusually thick-shelled eggs. Sci. Nat. 105, 10 (2018).

Davies, N. B. Cuckoos Cowbirds and other Cheats (T & A D Poyser, 2000).

Spottiswoode, C. N. The evolution of host-specific variation in cuckoo eggshell strength. J. Evol. Biol. 23, 1792–1799. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02010.x (2010).

Langmore, N. E. et al. The evolution of egg rejection by cuckoo hosts in Australia and Europe. Behav. Ecol. 16, 686–692. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/ari041 (2005).

Rohwer, S., Spaw, C. D. & Røskaft, E. Costs to northern orioles of puncture-ejecting parasitic cowbird eggs from their nests. The Auk 106, 734–738 (1989).

Brooker, M. G., Brooker, L. C. & Rowley, I. Egg deposition by the bronze-cuckoos Chrysococcyx basalis and Chrysococcyx lucidus. Emu 88, 107–109. https://doi.org/10.1071/Mu9880107 (1988).

McClelland, S. C. et al. Embryo movement is more frequent in avian brood parasites than birds with parental reproductive strategies. Proc. R. Soc B-Biol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.1137 (2021).

Gosler, A. G. & Wilkin, T. A. Eggshell speckling in a passerine bird reveals chronic long-term decline in soil calcium. Bird Study 64, 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/00063657.2017.1314448 (2017).

Lundholm, C. E. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis in eggshell gland mucosa as a mechanism for P, P’-DDE-induced eggshell thinning in birds: A comparison of ducks and domestic-fowls. Comp. Biochem. Phys. C 106, 389–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-8413(93)90151-A (1993).

Bitman, J., Cecil, H. C. & Fries, G. F. DDT-Induced inhibition of avian shell gland carbonic anhydrase: A mechanism for thin eggshells. Science 168, 594–596. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.168.3931.594 (1970).

Ratcliffe, D. A. Changes attributable to pesticides in egg breakage frequency and eggshell thickness in some British birds. J. Appl. Ecol. 7, 67-+. https://doi.org/10.2307/2401613 (1970).

Bouwman, H., Govender, D., Underhill, L. & Polder, A. Chlorinated, brominated and fluorinated organic pollutants in African Penguin eggs: 30 years since the previous assessment. Chemosphere 126, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.12.071 (2015).

Bleu, J., Agostini, S., Angelier, F. & Biard, C. Experimental increase in temperature affects eggshell thickness, and not egg mass, eggshell spottiness or egg composition in the great tit (Parus major). Gen. Comp. Endocr. 275, 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2019.02.004 (2019).

Picman, J. & Pribil, S. Is greater eggshell density an alternative mechanism by which parasitic cuckoos increase the strength of their eggs?. J. Ornithol. 138, 531–541. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01651384 (1997).

Lopez, A. V. et al. How to build a puncture- and breakage-resistant eggshell? Mechanical and structural analyses of avian brood parasites and their hosts. J. Exp. Biol. 224, jeb243016. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.243016 (2021).

Soler, M., Rodriguez-Navarro, A. B., Perez-Contreras, T., Garcia-Ruiz, J. M. & Soler, J. J. Great spotted cuckoo eggshell microstructure characteristics can make eggs stronger. J. Avian Biol. 50, e02252. https://doi.org/10.1111/jav.02252 (2019).

D’Alba, L. et al. Evolution of eggshell structure in relation to nesting ecology in non-avian reptiles. J. Morphol. 282, 1066–1079. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.21347 (2021).

Legendre, L. J. & Clarke, J. A. Shifts in eggshell thickness are related to changes in locomotor ecology in dinosaurs. Evolution 75, 1415–1430. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.14245 (2021).

Le Roy, N., Stapane, L., Gautron, J. & Hincke, M. T. Evolution of the avian eggshell biomineralization protein toolkit: New insights from multi-omics. Front. Genet. 12, 672433. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2021.672433 (2021).

Medina, I. & Langmore, N. E. Batten down the thatches: Front-line defences in an apparently defenceless cuckoo host. Anim. Behav. 112, 195–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2015.12.006 (2016).

Starling, M., Heinsohn, R., Cockburn, A. & Langmore, N. E. Cryptic gentes revealed in pallid cuckoos Cuculus pallidus using reflectance spectrophotometry. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 273, 1929–1934 (2006).

Abernathy, V. E., Troscianko, J. & Langmore, N. E. Egg mimicry by the Pacific koel: Mimicry of one host facilitates exploitation of other hosts with similar egg types. J. Avian Biol. 48, 1414–1424. https://doi.org/10.1111/jav.01530 (2017).

Green, R. E. An evaluation of three indices of eggshell thickness. Ibis 142, 676–679. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919X.2000.tb04468.x (2000).

Green, R. E. Long-term decline in the thickness of eggshells of thrushes, Turdus spp., in Britain. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. B: Biol. Sci. 265, 679–684. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1998.0347 (1998).

Igic, B. et al. Comparison of micrometer-and scanning electron microscope-based measurements of avian eggshell thickness. J. Field Ornithol. 81, 402–410 (2010).

Maurer, G., Portugal, S. J. & Cassey, P. A comparison of indices and measured values of eggshell thickness of different shell regions using museum eggs of 230 European bird species. Ibis 154, 714–724 (2012).

Becking, J. The ultrastructure of the avian eggshell. Ibis 117, 143–151 (1975).

Birkhead, T. et al. New insights from old eggs–the shape and thickness of Great Auk Pinguinus impennis eggs. Ibis 162(4), 1345–1354 (2020).

Riley, A., Sturrock, C., Mooney, S. & Luck, M. Quantification of eggshell microstructure using X-ray micro computed tomography. Br. Poult. Sci. 55, 311–320 (2014).

Kibala, L., Rozempolska-Rucinska, I., Kasperek, K., Zieba, G. & Lukaszewicz, M. Ultrasonic eggshell thickness measurement for selection of layers. Poult. Sci. 94, 2360–2363. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pev254 (2015).

Khaliduzzaman, A. et al. A nondestructive eggshell thickness measurement technique using terahertz waves. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–5 (2020).

Santolo, G. M. A new nondestructive method for measuring eggshell thickness using a non-ferrous material thickness gauge. Wilson J. Ornithol. 130, 502–509. https://doi.org/10.1676/17-035.1 (2018).

Marini, M. A. et al. The five million bird eggs in the world’s museum collections are an invaluable and underused resource. Auk 137, ukaa036. https://doi.org/10.1093/auk/ukaa036 (2020).

Brooker, M. G. & Brooker, L. C. Cuckoo hosts in Australia. Aust. Zool. Rev. 2, 1–67 (1989).

Higgins, P. J. Vol. Volume 4: Parrots to Dollarbird (Oxford University Press, 1999).

Higgins, P. J. & Peter, J. M. Vol. 6: Pardalotes to Shrike-Thrushes (Oxford University Press, 2002).

Higgins, P. J., Peter, J. M. & Cowling, S. J. Vol. 4: Parrots to Dollarbird (Oxford University Press, 2006).

Higgins, P. J., Peter, J. M. & Steele, W. K. Vol. 5: Tyrant-flycatchers to Chats (Oxford University Press, 2001).

Landstrom, M., Heinsohn, R. & Langmore, N. E. Clutch variation and egg rejection in three hosts of the pallid cuckoo Cuculus pallidus. Behaviour 147, 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1163/000579509X12483520922043 (2010).

Abernathy, V. E., Johnson, L. E. & Langmore, N. E. An experimental test of defenses against avian brood parasitism in a recent host. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9, 244. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2021.651733 (2021).

Landstrom, M. T., Heinsohn, R. & Langmore, N. E. Does clutch variability differ between populations of cuckoo hosts in relation to the rate of parasitism?. Anim. Behav. 81, 307–312 (2011).

Peterson, S. H. et al. Avian eggshell thickness in relation to egg morphometrics, embryonic development, and mercury contamination. Ecol. Evol. 10, 8715–8740. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.6570 (2020).

Attard, M., Medina, I., Langmore, N. E. & Sherratt, E. Egg shape mimicry in parasitic cuckoos. J. Evol. Biol. 30, 2079–2084 (2017).

Birchard, G. F. & Deeming, D. C. Avian eggshell thickness: Scaling and maximum body mass in birds. J. Zool. 279, 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00596.x (2009).

Orme, D. et al. The caper package: Comparative analysis of phylogenetics and evolution in R. R Packag. Vers. 5, 549–593 (2013).

Jetz, W., Thomas, G. H., Joy, J. B., Hartmann, K. & Mooers, A. O. The global diversity of birds in space and time. Nature 491, 444–448. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11631 (2012).

Schliep, K. P. Phangorn: Phylogenetic analysis in R. Bioinformatics 27, 592–593. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btq706 (2011).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing, (2013).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Leo Joseph, Margaret Cawsey, Ian Mason, Dave Spratt, Robert Palmer, Kerensa McElroy, Caitlin Cherryh of the CSIRO Australian National Wildlife Collection, (grid.510155.5) for assistance in undertaking this research. We also thank Simon Checksfield, Alexander Schmidt-Lebuhn and Andrew Young (administration and resources; NRCA) and Shane A. Richards (statistical advice; UTAS). This study was supported financially by the CSIRO Summer Scholar Program, a National Research Collections Australia Capital Expenditures Grant to CEH and Australian Research Council Grant DP180100021 to NEL, CEH and Rebecca Kilner.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was conceived by N.E.L. and C.E.H. Eggshell specimens were supplied from the Australian National Wildlife Collection by C.E.H. A.C.G. designed the experiments and collected the data, with assistance from N.E.L. and C.E.H. C.E.H, I.M. and A.G. prepared the figures. All authors contributed to data analysis and drafting the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Holleley, C.E., Grieve, A.C., Grealy, A. et al. Thicker eggshells are not predicted by host egg ejection behaviour in four species of Australian cuckoo. Sci Rep 12, 6320 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09872-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09872-9

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.