Abstract

While the importance of social affect and cognition is indisputable throughout the adult lifespan, findings of how empathy and prosociality develop and interact across adulthood are mixed and real-life data are scarce. Research using ecological momentary assessment recently demonstrated that adults commonly experience empathy in daily life. Furthermore, experiencing empathy was linked to higher prosocial behavior and subjective well-being. However, to date, it is not clear whether there are adult age differences in daily empathy and daily prosociality and whether age moderates the relationship between empathy and prosociality across adulthood. Here we analyzed experience-sampling data collected from participants across the adult lifespan to study age effects on empathy, prosocial behavior, and well-being under real-life circumstances. Linear and quadratic age effects were found for the experience of empathy, with increased empathy across the three younger age groups (18 to 45 years) and a slight decrease in the oldest group (55 years and older). Neither prosocial behavior nor well-being showed significant age-related differences. We discuss these findings with respect to (partially discrepant) results derived from lab-based and traditional survey studies. We conclude that studies linking in-lab experiments with real-life experience-sampling may be a promising venue for future lifespan studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Throughout the lifespan, satisfying social interactions are key for well-being (e.g.,1) as well as for mental and physical health (e.g.,2). Experiencing empathy in response to someone’s suffering, a feeling that is believed to trigger prosocial behavior, is an important ingredient for establishing and maintaining relationships with other people3,4. Whilst it is certainly indisputable that social functioning remains important throughout the adult lifespan5,6, findings on how empathy and prosociality develop and interact over the course of adulthood are still mixed.

Research on the lifespan development of empathy is often built on the distinction of affective components (affect sharing, empathic concern, compassion) from cognitive components (perspective taking) of empathy7,8. In two recent laboratory studies using a naturalistic paradigm to dissociate both affective and cognitive aspects of understanding others9,10, we did not observe age-related differences in affect sharing. However, and in line with our expectations, empathic concern was found to be enhanced whereas perspective taking ability decreased in older compared to younger adults. Whilst this pattern of findings contributes to an emerging prevalent view of reduced cognitive but preserved or increased affective empathy in older vs. younger adults (8 for a recent review), there is substantial heterogeneity in the literature, particularly when considering adult age effects across the lifespan.

With respect to experimental studies, there is some evidence for an age-related increase in task-based (i.e., less naturalistic behavioral measure conducted in the lab) empathic concern11, and affect sharing12 in some studies. However, other comparable studies find no evidence for significant age-related differences with respect to task-based empathic concern13,14, and affect sharing15. The same inconsistencies are observed in terms of perspective taking when measuring the construct in behavioral tasks. Overall, meta-analytic evidence points towards a decrease of perspective taking ability16 but, there are other experimental studies showing no evidence for age differences in perspective taking17,18,19,20. With respect to studies that measure empathic concern, affect sharing, or perspective taking with self-report, results have suggested linear and inversed U-shaped relationships between age and self-reported empathic concern11,21 and perspective taking21, as well as age-related declines in self-reported affect sharing22,23.

The understanding of developmental change and stability with respect to prosociality has become an important research topic24,25. Similar to the heterogeneity of findings in the domain of empathy, previous research on adult age differences in prosocial behavior has yielded mixed results. Experimental age-comparative laboratory studies have often revealed a higher degree of prosocial behavior in older compared to younger adults14,26,27,28,29, and have shown a linear increase in prosociality when examined across the adult lifespan11,30,31. There are, however, other studies which do not find such age-related increases in prosocial behaviors neither in experimental tasks or self-reported prosocial measures when comparing younger and older adults32,33, when comparing middle- and older age groups34, nor when looking at age correlations across adulthood35,36.

Social psychology and neuroscience research suggests that feeling empathy with a person usually results in greater prosocial behavior (for reviews see37,38,39,40). Some previous studies have asked whether this link might be moderated by adult. Experimental studies in the laboratory demonstrate enhanced prosocial behavior after an empathy induction in older adults (compared to younger adults)14 as well as age-related linear increases in prosocial behavior across younger, middle aged, and older adults that were partially mediated by empathic concern11. Age was also found to positively moderate the association of self-reported prosocial behavior and empathic concern, but only in participants younger than 75 years34. However, another study did not find age-related differences regarding the link between empathy and prosocial behavior when comparing younger and older adults27.

The question of whether subjective well-being, used as an umbrella term for feelings of happiness, a sense of purpose in life, and life satisfaction2, changes over the course of the adult lifespan is a research topic that has also attracted much attention over the last decades (e.g.,41,42). Most prominently, an influential lifespan theory of affective development (‘socio-emotional selectivity theory’43) postulates higher socio-emotional well-being in older adults. It is argued that when individuals perceive their remaining lifetime as limited, they tend to prioritize present goals like optimizing socio-emotional well-being44. This is thought to be related to a “positivity effect”, i.e., a motivational shift to positive over negative information processing45,46,47, even though there are studies that do not find evidence for age-related differences regarding this processing bias for positive stimuli48,49. Large-scale international surveys across several countries often reveal a U-shaped association between age and evaluative well-being, illustrating higher well-being in younger and older adult age (e.g.,50,51). Studies using ecological momentary assessment or other daily measures also show a U-shaped relationship of adult age and life satisfaction52, or a curvilinear relationship of age and negative emotional experience53. Notwithstanding, there is a current debate about the putative U-shaped pattern, including critiques with respect to its robustness and generalization54,55,56. Prosocial behavior and well-being have been suggested to be associated with each other, and some studies have suggested that their link is moderated by age. In a recently published large-scale daily diary study57, younger adults’ prosocial behavior was associated with both costs and benefits, in that they experienced both greater negative affect and more positive experiences at the same time, while these associations were both attenuated in older adults. This was interpreted as a decreasing influence of prosociality on well-being over the course of the life span. In contrast, earlier age-comparative studies have pointed towards more beneficial effects of volunteering on life satisfaction in older compared to younger adults58.

Considering the lifespan developmental findings (and their considerable heterogeneity) reviewed above, an intriguing open research question is whether there are adult age differences in empathy, prosociality, and well-being as they occur in daily life. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) is a method which is well-suited to capture these processes in real life. EMA is a relatively new method, with advantages like increased ecological validity, and decreased recall bias, while measuring within-person variability and change over a short time period59. These advantages may be particularly important for lifespan developmental studies, as recall bias60 and within intra-individual variability61 have been shown to be subject to age effects in different behavioral contexts. Unfortunately, and to the cost of external validity, to date only a small list of studies4,62,63 examined empathy and prosociality using EMA, most of them with no focus on adult age differences. With the current study we aimed to fill this gap by leveraging the advantages of EMA and investigating daily empathy, prosociality, and well-being under real-life circumstances, repeatedly per day within person. To this end we analyzed smartphone based experience-sampling data recently published by Depow and colleagues63. The primary goal of Depow and colleagues’ study63 was to analyze the perception of empathy in everyday lives and the prediction of prosocial behavior and subjective well-being (defined as feelings of happiness and purpose of life). They used quota-sampling to ensure their sample was representative of the U.S. adult population on key demographics, including age. However, age effects were not part of their original analysis. Given the growing interest in age-related differences regarding components of the social mind24 and the lack of real-life data in this field, we used the data acquired and provided openly by Depow et al.63 to examine age effects with regards to daily empathy, prosocial behavior, and well-being. Separating contributions of within- from between-subject variability, we aimed to investigate whether age influences daily empathy, prosocial behavior, and well-being, as well as their interactions. Of note, in the current study, empathy was defined as an umbrella term, subsuming the three different subcomponents emotion sharing, compassion, and perspective taking. Prosocial behavior was defined as an opportunity to help someone.

Based on the heterogeneity of age-related findings regarding the constructs of empathy and prosocial behavior as reviewed above, and considering inconsistencies in the definition of empathy, we had undirected hypotheses in terms of age differences in daily empathy and prosocial behavior. In line with previous results50,51,52, we expected a U-shaped relationship of adult age with well-being (measured in terms of happiness and sense of purpose), with higher well-being in younger and older adults. Based on a positivity bias postulated for older adults in the lifespan theories of emotional aging45,46,47, we expected older adults to experience more empathy in contexts with positive valence (i.e., situations where the target emotion was positive). Based on a previous lab-based study34, we hypothesized an attenuated relationship of empathy and prosocial behavior in the older age range. Furthermore, based on the literature57 we assumed a greater relationship of empathy and well-being with increasing age and expected the same age-related pattern with respect to the link between prosocial behavior and well-being.

Results

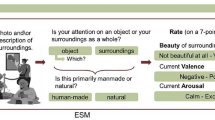

In the current study we reanalyzed open-source data from Depow and colleagues63, using EMA in a demographically representative sample across the adult lifespan (final sample n = 243, 136 females, 104 males, and 3 others) to measure daily empathy, prosociality, and well-being. In the main experience sampling survey participants underwent seven surveys per day for one week, including four levels, building on each other (see Fig. 1). The first level measured daily well-being and prosocial behavior, as well as opportunities to empathize with someone or any situations where the participant could be the target of empathy. In case they had reported an empathy opportunity before, on the next (2nd) level participants answered questions about their actual feelings of empathy. On the third level the subcategories emotion sharing, perspective taking, and compassion were investigated. On the fourth level the extent, difficulty, and confidence for every indicated subcomponent were probed. Depow and colleagues63 collected information on participants’ age by asking about participants’ age group; participants did not provide information on their exact age. Age was binned into four ordered age groups, based on the original classification from Depow and colleagues63: (1) 18 to 34 years (n = 71, 45 females, 3 “other), (2) 35 to 44 years (n = 59, 28 female), (3) 45 to 54 years (n = 51, 34 female), and (4) 55 years and older (n = 62, 29 female). Thus, age group entered all models as a continuous variable, based on the assumption of ordinality and continuity (e.g.,11,64). Outcome variables derived from all four levels of the survey (see Fig. 1) were analyzed. All outcome variables were analyzed by using two (generalized) mixed-effect models, one including age group as linear predictor and one including age group both as a linear (age group) and a quadratic predictor (age group2). We report p-values corrected based on the false-discovery rate.

Daily survey design, visualizing the different survey levels and related questions. Only the questions relevant for the current study are depicted here. For further details, and a full study protocol, see Depow and colleagues63. Note that empathy (level 2) was assessed as an umbrella term, thus, questions about the subcomponents (level 3) emotion share, perspective taking, and compassion were only rated if the participant indicated to have actual feelings of empathy on level 2 of the survey. For each reported subcomponent on level 3, participants were asked about confidence, extent, and difficulty on level 4 of the survey.

Adult age differences in everyday empathy

Empathy opportunities

Regarding the first level of the survey (see Fig. 1), i.e., the frequency of empathy opportunities, and the frequency of being the target of empathy, no age-related differences were found (empathy opportunities: b = 0.01, SE = 0.08, z = 0.16, p = 0.872, adj. p = 0.872, r = 0.00; target of empathy: b = 0.02, SE = 0.10, z = 0.21, p = 0.834, adj. p = 0.872, r = 0.01). Reassuringly, this null effect of age suggests that potential age differences in all subsequent analyses are unlikely to be affected by baseline differences in how often different age groups experienced an opportunity to empathize in the first place.

Experiencing empathy

With respect to the actual feelings of empathy (2nd level of the survey), significant linear as well as quadratic effects of age were observed (linear: b = 0.37, SE = 0.15, z = 2.44, p = 0.015, r = 0.10; quadratic: b = -0.41, SE = 0.18, z = -2.24, p = 0.025, r = -0.11). Daily feelings of empathy increased across the first three age groups, from 18 to 44 years, but, as the significant quadratic trend suggests, show a tendency to decrease beyond these ages, in those 55 years and older (see Fig. 2A).

Daily empathy. The y-axis shows the proportions of answering ‘yes’ when asked about the actual feelings of empathy relative to the total amount of answered surveys. (A) Adult age differences regarding actual feelings of empathy. Significant quadratic association of actual feelings of empathy and age. (B) Interaction between valence (negative, neutral, or positive target emotion) of the empathy opportunity and age on reported feelings of daily empathy. Age did not moderate the link between the valence of the situation and actual feelings of empathy.

In lifespan developmental theories, a positivity bias for older as compared to younger adults has been suggested45,46,47. Here, we tested this hypothesis with respect to the role of emotional valence (i.e., positive, neutral, or negative) of the empathy opportunity on actual feelings of empathy. That is, we tested for an interaction of age group with valence of the empathy opportunity. As reported in Depow and colleagues63, subjects generally showed higher actual feelings of empathy after positive empathy opportunities; however, contrary to our expectation this effect was not moderated by age (Chi2 (2) = 0.27, p = 0.872, see Fig. 2B).

Subcategories of empathy

Regarding the subcomponents of empathy (3rd level of the survey, Fig. 1), no significant age-related differences (neither linear, nor quadratic) were found for emotion sharing (b = -0.17, SE = 0.13, z = -1.31, p = 0.189, adj. p = 0.567, r = -0.05), perspective taking (b = 0.01, SE = 0.14, z = 0.06, p = 0.952, adj. p = 0.952, r = 0.00), or compassion (b = 0.18, SE = 0.35, z = 0.52, p = 0.601, adj. p = 0.902, r = 0.05). Note that ratings of the subcomponents of empathy were only provided by those participants who indicated actual feelings of empathy on the second level of the survey. Thus, while we observe age-related differences in the tendency to experience actual feelings of empathy in general (2nd level), among the proportion of participants who experienced actual feelings of empathy, no age differences with regard to the subcomponents were observed. Further, after adjusting p-values, no age-related differences were observed in the extent, difficulty, and confidence (4th level) of the different subcomponents: emotion sharing, perspective taking, and compassion (all bs < 0.04, all SEs < 0.08, all ts < 0.96, all adj. ps > 0.081, all rs < 0.20; see supplementary table S1).

Depow and colleagues63 showed that the co-occurrence of the three subcomponents of empathy (i.e., emotion sharing, perspective taking, and compassion) was very high. Thus, the different components of empathy seem to mainly co-occur in everyday life. Analyzing age effects on the co-occurrence of the empathy subcomponents using a chi2-tests, we did not find any significant effect of age (all chi2s < 5.76, all ps > 0.124; see supplementary figures S1-4).

Adult age differences in prosociality

Contrary to our expectations, we did not find significant age-related differences with respect to daily prosocial behavior (b = 0.007, SE = 0.08, z = 0.08, p = 0.934, r = 0.00, see Fig. 3A). Depow and colleagues63 found significant associations between different aspects of everyday empathy (e.g., empathy opportunity, actual feelings of empathy, subcomponents) and prosocial behavior. In the current analysis most of those effects were not significantly moderated by participants’ age (all adj. ps > 0.227, see Table 1). Only the interaction term of reported empathy opportunities and age as quadratic and linear term, respectively, significantly predicted prosocial behavior as a within-subject effect (linear: b = -0.13, SE = 0.05, z = -2.80, p = 0.005, adj. p = 0.024, r = -0.04, quadratic: b = 0.15, SE = 0.06, z = 2.72, p = 0.006, adj. p = 0.024, r = 0.04). Across all age groups the experience of an empathy opportunity was associated with higher prosocial behavior, but this effect was more pronounced in the middle-aged groups than in the youngest and oldest groups (see Fig. 3B).

Daily prosocial behavior. The y-axis shows the proportions of answering ‘yes’ when asked about acting prosocially relative to the total amount of answered surveys. (A) Adult age differences in prosocial behavior. No significant association between age and prosocial behavior was found. (B) Within-subject effect of empathy opportunity x age on prosocial behavior. All age groups showed more prosocial behavior after an empathy opportunity. A quadratic effect of age group indicated that this effect was more pronounced in the middle-aged groups than in the younger and older age group.

Adult age differences in subjective well-being

Overall, and contrary to our a-priori hypothesis, we did not find significant adult age effects on daily subjective well-being (b = 0.11, SE = 0.08, t(233) = 1.48, p = 0.141, r = 0.10, see Fig. 4A). In Depow and colleagues’63 analyses, different aspects of daily empathy (e.g., empathy opportunity, and actual feelings of empathy) were associated with subjective well-being. Thus, in a next step, we analyzed whether such an association of different aspects of daily empathy and well-being, as reported on the group-level, was moderated by age. No significant interaction with age was revealed (all adj. ps > 0.154, see Table 2). We found a significant interaction effect between age and prosocial behavior on subjective well-being, but only as a within-subject effect (b = 0.03, SE = 0.01, t(6315) = 2.62, p = 0.009, r = 0.03; see Table 2). As can be seen from Fig. 4B, within-person, across all age groups, higher well-being was associated with acting prosocially before. However, the difference in well-being as a function of an opportunity to act prosocially was slightly more pronounced in the younger age groups (see Fig. 4B).

Daily well-being. (A) Adult age differences in subjective well-being. No significant association between age and well-being. (B) Within-subject effect of prosocial behavior x age on well-being. Positive association between well-being and acting prosocially, irrespective of participants’ age. Stronger association of a prosocial act with wellbeing in younger adults.

Discussion

In this study, we used experience sampling data63 to test adult age differences with respect to empathy, prosociality, and well-being. Based on a representative sample, we were able to yield several new insights into the lifespan development of these important social functions, as well as their interactions in daily life.

With respect to daily empathy, we found a (small) linear effect of age on empathy across the lifespan, which is in line with postulated stable or even increased socio-affective processes in older adults, as measured in laboratory studies (e.g.,9,10,11). Interestingly, in this ecologically valid description of a near-representative sample we found an inverted U-shaped relationship of age and empathy. This pattern suggests that daily empathy increased from 18 years on, with a peak in midlife, but decreased slightly in the oldest group (55 years and older). Notably, the empathy level of the oldest group was higher than the one of the youngest. This pattern is in line with the findings from O’Brien and colleagues21, with respect to their quadratic associations in self-reported trait empathic concern and perspective taking. Further, there is cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence that moving from early to middle adulthood is associated with more stable dispositional traits like agreeableness65 and that the period of middle adulthood is also linked to highest values of generativity66, potentially rendering empathy a particularly relevant skill in this period of life.

When comparing the results of this experience-sampling study to previous research on the lifespan development of empathy, it is important to note that the definition of the construct empathy varies across studies, which has been criticized recently67 reminiscent to a discussion about so-called “Jingle-Jangle fallacies”68,69. Such an inconsistency in the definition of empathy also affects studies investigating age differences in empathy. In the current study, empathy was regarded as an umbrella term spanning the subcomponents emotion sharing, compassion, and perspective taking; consequently, participants only provided ratings for these subcomponents when they had indicated feelings of empathy before. Based on this operationalization, a high co-occurrence between emotion sharing, perspective taking, and compassion was reported, and no age-related differences regarding the three subcomponents nor their co-occurrence were found. Previous ageing studies differentiated (emotional) empathy in terms of affect sharing, from compassion, and perspective taking (e.g.,9,10), by assessing them independently from each other, which revealed differential age-related findings for each construct (7,8 for review).

The majority of studies on empathy thus far focused, by design, on empathy exclusively in the context of negative stimuli and most often with strangers in a lab (e.g., EmpaToM-Paradigm70, as used in9). A commendable recent exception by Ziaei and colleagues71 included positive and negative stimuli when measuring empathy in a behavioral task in the lab, demonstrated that older adults responded significantly slower to negative than to positive stimuli. Interpreting this result, the authors argued there is a greater difficulty in processing negative emotions in older adults. The dataset used for the current analyses offered the opportunity to examine age effects in interaction with the valence of a real-life situation. Indeed, Depow and colleagues63 showed that empathy was reported more frequently following situations with a positive valence. In contrast to a hypothesized positivity bias71, this effect was not significantly enhanced with increasing age. This is in line with a previous study conducted in the lab48 which could not find behavioral age-related differences in working memory performance as a function of emotional valence. However, the experience of affective empathy, particularly compassion72, be it in an emotionally positive or negative context, might be rewarding in itself or subsequently lead to satisfying social interactions (if, e.g., followed by prosocial behavior as demonstrated in the current dataset). In this regard, experiencing enhanced empathy in both positive and negative domains is in line with the lifespan goals suggested by emotional selectivity theory43, namely an enhanced pursuit of emotionally satisfying interactions in midlife and older age.

In this experience-sampling study, no adult age differences in prosocial behavior were observed. This is in contrast to most laboratory studies using economic decision-making tasks (e.g., dictator game, public good game), or experimental helping/donating paradigms, which showed pronounced prosocial behavior in older adults (e.g.,14,26,73). Also studies using self-report measures in terms of validated questionnaires, showed greater prosociality with advancing age, by comparing younger vs. older adults74, across younger and middle-old adults75, or across the whole adult lifespan76,77. While these inconsistencies in results may be argued to be due to these studies not measuring behavior in real life, discrepancies also occurred when comparing the current results with studies that measured real-life prosociality. Cavallini et al.34 reported a significant negative association between age and self-reported real life prosocial activities, arguing that real-life prosocial behavior is more cognitively and physically demanding. An important difference between the study by Cavallini and colleagues34 and the current study is the higher age on average, as they only included participants aged 55 years and older, but no younger age group. Thus, our comparably young sample here might not be ideally suited to detect potential effects of physical and cognitive demands on an aging effect in prosocial behavior. Further, in Cavallini and colleagues’ study34 prosocial behavior was not measured using EMA (e.g., in the last 15 min), but based on a self-reported questionnaire which asked about the recalled frequency of acting prosocially in a pre-defined set of prosocial scenarios during the last 12 months. It is possible different types of prosocial acts are assessed by self-reported questionnaires compared to EMA measures. Cavallini et al.’s34 method has potentially captured acts that are more memorable over a longer time frame and thus might have been more resource-intense (e.g., charitable giving). In the current study, prosociality is defined more broadly (as anything including direct or indirect help, or to make another person feel better). Thus, daily acts (including smaller acts) of prosociality (e.g., holding the door open) would be included in the EMA-based self-report. Consequently, it is plausible that EMA-based self-report captures acts that might have been forgotten otherwise. Due to such memory effects, or recall biases, which are more susceptible in global retrospective reports78, a difference in the reference time frame of self-report (12 months in Cavallini et al.’s study34 vs. 15 min in the current study) could be particularly relevant for lifespan studies, as there is evidence for an increased memory-experience gap in older individuals60.

We expected an attenuated relationship of empathy and prosocial behavior with higher age34 which was only partially confirmed. Age did not modulate the associations between actual feelings of empathy, nor of any of its subcomponents with prosocial behavior. However, the interaction between the opportunity to empathize, and age, both as a linear and a quadratic term on prosocial behavior was statistically significant as a within-person effect. Meaning all age groups showed more prosocial behavior when there was an empathy opportunity. However, this stronger tendency to act prosocially if there was a situation eliciting empathy (as compared to when there was none) was found to be slightly more pronounced in the middle-aged group of the sample. This is different compared to the results by Cavallini and colleagues34, which showed that with increasing age (> 75 years), daily prosocial behavior was less driven by empathic concern. When comparing these results. When comparing these results it should be noted the participants in Cavallini and colleagues34 were considerably older, and the self-reported measure reflected memories of prosocial acts within the last 12 months. Taken together, it leaves an open research question on what drives prosocial behavior in older adults’ everyday life.

In the current study, we did not observe the often-found U-shaped age-related pattern of self-reported well-being previously found in larger studies (e.g.,50,52). Subjective well-being was assessed by two different questions, merged into one universal well-being score, covering hedonic well-being (i.e., experienced happiness) and eudaimonic well-being (i.e., purpose of life). Even though eudaimonic well-being gets more attention in the current literature2,79, most studies that have found a U-shaped pattern of subjective well-being emphasized a hedonic operationalization of well-being (e.g.,51,54). However, beyond the measurement level, it is noteworthy to discuss the recent debate about the robustness and generalization of the putative U-shaped pattern with regard to the association of adult age and well-being54,55,56. A recently published study54 challenged this often as a typically assumed U-shaped pattern, by revealing inconsistent findings with respect to the association of age and well-being, both in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Additionally, it is argued that age effects on well-being could be an epiphenomenon of other variables, reflecting the current life circumstances associated with ageing (e.g., income, education), fixed effects like personality traits, or selection effects which might differ as a function of age group51,56,80.

We confirmed a hypothesized moderation effect of age on the link between daily prosocial behavior and subjective well-being. Across all age groups, subjective well-being within a person was higher when a prosocial act had been was performed 15 min before. However, this trend was attenuated with increasing age. This is in line with Chi and colleagues’57 recently published observations about a decreased influence of prosocial behavior on well-being in older compared to younger adults. Interestingly, an earlier study58 observed the opposite when looking at the long-term impact (i.e., over 3 years of time) of volunteering in a longitudinal survey, namely enhanced well-being as a result of volunteering in older compared to younger adults. Given shrinking time horizons for older versus younger adults, which have been associated with different (socio-emotional) life goals43, it would be an interesting venue for future studies to differentiate short- and long-term consequences of prosocial behaviors and age differences therein.

It is interesting to note that across many of the measured variables, inconsistencies (and indeed, often times null effects of age) with previously reported age-related results were observed. More specifically, compared to published reports on effects of adult age on prosocial behaviors, well-being, and empathy, we observed null effects of age on prosociality and well-being, and a small quadratic effect on empathy. In the following, we speculate about where these discrepancies may arise from.

First, such discrepancies may reflect different motivational aspects elicited by different study designs (e.g., in-lab vs. real-life, experimental vs. self-reported81). On one hand, there is evidence for external validity of commonly used tasks in the domain of prosociality82,83. On the other hand, a previous study showed that lab-induced prosocial behavior differed drastically from real-life prosocial behavior in a natural-field dictator game. The authors interpreted these findings as the authors interpreted as inflated prosocial behavior elicited by the lab context84. Further, observability has been shown to be associated with higher prosocial behavior85, underpinning the assumption that lab-induced prosocial behavior might be different in nature from prosocial behavior in real life. Further, different studies identified differential drivers of empathy. The likelihood to engage in empathy-eliciting situations increased with monetary incentives, and also when the target of empathy was familiar86. It has also been found increased perceived closeness leads to better perspective taking abilities in older adults87,88, and both, our own age and the social interaction partner’s age affect these capacities89.

Second, it has been shown that the sampling strategy influences the degree of prosociality. Indeed, in many age-comparative studies, the younger age group might consist predominantly of students (e.g.,9,10), who have been demonstrated to display systematically less prosocial behavior in in-lab studies. This remains true when controlling for age in this population90. A strength of the current study is that the sample was quota-sampled on six key demographic variables (i.e., sex, ethnicity, education, geographic region, income, and age), even though representativeness might not be given with respect to other demographics (e.g., marital status, current living situation), as the sample is not random. Moreover, there was a reduced number of participants sampled from the youngest (18–24 years) and oldest (65 years and older) age group, which is why the two youngest and two oldest groups were merged for all analyses. Thus, conclusions about differences with respect to these groups, and comparability with ageing studies, which typically include a wider range of older adults, are limited.

A methodological strength of the dataset analyzed here is the experience-sampling method used to acquire data. EMA studies help to provide closer and deeper insights and to broaden our understanding of real differences across the lifespan by investigating the frequency, intensity, and complexity of different measures. Advantages lie in increased ecological validity, decreased recall bias, and the possibility to measure variability and change over a short time. Despite its many advantages, repeatedly responding to the survey could also have an influence on whether people notice empathy opportunities (for a more detailed discussion of representativeness, potential training, and fatigue-effects see Depow et al.63). Experience sampling also shares with other self-report measures its susceptibility to biases, like social desirability. More objective, implicit measures of empathy (e.g., physiological reactions towards others’ suffering) have been used in the lab and have also revealed age differences11,91. A limitation of the current study is that we exclusively relied on explicit EMA reports and did not include other, complementary measures of empathy. A recent study92 adopted a combined EMA-fMRI approach in young adults to show that affective components of empathy ratings assessed via EMA were associated with behavioral measures from an experimental empathy paradigm, but not with neural activation. Daily cognitive components of empathy ratings assessed using EMA were correlated with neural activation in the medial prefrontal cortex, but not significantly related to perspective taking performance in an experimental task. To gain a more comprehensive insight into the adult lifespan development of the social mind, such multi-modal designs combining EMA, experimental, and physiological measures93,94 are a promising venue for future lifespan studies.

Conclusion

Factors that contribute to, or result from, successful social interactions like empathy, prosocial behavior, and well-being are important throughout life. This analysis of cross-sectional experience-sampling data suggests that most of these constructs show no significant age-related differences when measured repeatedly via self-report in daily life. One exception was empathy. Here we observed a weak inverted U-shaped effect of age on empathy over the course of the lifespan. Future studies should take into account methodological differences stemming from varying study-designs and construct definitions, which might be one source of inconsistencies in age-related results in the literature. Multivariate studies combining standardized in-lab experiments with real-life experience-sampling data are a promising venue for future lifespan studies on the social mind.

Methods

The current study is based on the publicly available dataset from Depow and colleagues63 who used ecological momentary assessment to increase ecological validity and to explore within-person differences. In the current study, we focused on analyzing adult age-related differences on different aspects of daily empathy, daily prosocial behavior, and daily subjective well-being. In the following, we reiterate the methodological approach used by Depow and colleagues63.

Participants

Quota-sampling was used for a nearly representative U.S. sample, in cooperation with the survey company Qualtrics (Qualtrics®, 2002; www.qualtrics.comwww.qualtrics.com). Overall, 3486 participants filled in a demographic questionnaire, including informed consent about participating in a “Daily Interactions’ study”. In a next step, 841 quota-sampled participants were invited via email to participate in the study. Altogether, 375 completed the baseline survey (trait questionnaire measures, instruction to download the app, glossary of the terms), whereas 285 participants completed the full experience sampling for one week, seven times per day. Participants were excluded if they missed more than 7 surveys in total, which resulted in a sample of 246 participants. Three more participants, were excluded from the current analysis due to missing information regarding their age. In the dataset from Depow and colleagues 63 age was originally measured in six age groups. The groups were divided into (1) 18 to 24 years (n = 14), (2) 25 to 34 years (n = 57), (3) 35 to 44 years (n = 59), (4) 45 to 54 years (n = 51), (5) 55 to 64 years (n = 42), and (6) 65 years and older (n = 20). Due to comparably small sample sizes in the youngest and oldest age groups Depow and colleagues63 merged the two youngest and the two oldest age groups for a more homogenous sample size across the groups, an approach which we adopted for the current analysis. Thus, the final sample consisted of 243 participants (18–34: n = 71, 45 female, 3 “other”; 35–44: n = 59, 28 females; 45–54: n = 51, 34 female; 55 and older: n = 62, 29 female). The age groups differed significantly with respect to their gender and education distribution, but not in surveys answered, income, and religiosity (see Table 3 for descriptive and interferential statistics). Participants answered a total of 7141 surveys, which we consider a dataset characterized by a high degree of ecological validity. Due to a bug in the experience sampling procedure in the original study by Depow et al.63, a very small number of participants (n = 58 out of a total of n = 243 participants), received prompts to fill out the survey more often, and sometimes within a shorter time interval (i.e., < 15 min). These cases could be problematic, since the experience sampling was done within a time interval that was shorter than 15 min, which may not have capture participants’ responses to independent events/experiences. Thus, all surveys that were prompted < 15 min after a previous survey were excluded from the analyses (a total of n = 110 surveys from a total of n = 7251 surveys, corresponding to only 1,5% of all data). Also due to this issue, we were able to include eight surveys per day for a minority of participants (n = 18), instead of the intended maximum of seven surveys per day, all of which by time windows ≥ 15 min. For information on how often participants reported an empathy opportunity, having been the target of empathy, and prosocial behavior, as well as reported well-being see Table 4. Further, we observed differences in how often participants reported an empathy opportunity, an opportunity to be the target of empathy, and prosocial behavior, as well as the reported well-being scores (i.e., questions asked on the first level of the survey) as a function of the different survey days. While these differences are mainly driven by the first day of the survey compared to later points in time, they are apparent across all age groups (compare Table 4) and do not differ significantly between the different age groups (all adj. ps > 0.236). All participants provided informed consent regarding their participation in the project, and were told they were free to cease their participation at any point. All procedures were approved by the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board to ensure they adhered to relevant ethical guidelines for human data collection and usage (Protocol No. 36941).

Procedure

Baseline survey

Participants first underwent a baseline survey to collect demographic information and trait measures (compare63). The baseline survey included a glossary of the important terms (empathy opportunity, emotion and sharing, perspective taking, compassion, prosocial behavior), to ensure that all participants would understand the concepts in the same way. For detailed information about the materials see Depow and colleagues63.

Experience-sampling survey

After the baseline survey, participants underwent seven short surveys per day, sent between 10am and 10 pm for one week, delivered by Metricwire (MetricWire®, 2013). Surveys were sent semi randomly, within a 90-min window, with a minimum 15 min gap between surveys. Surveys expired 20 min after the prompt. The daily survey consisted of four levels that were built on each other (see Fig. 1). On the first level, participants were questioned about their current subjective well-being, and if they had an opportunity to empathize (empathy opportunity), to be the target of empathy, or to act prosocially in the last 15 min. If an empathy opportunity had occured in the last 15 min, further details relating to this opportunity were acquired. On the second level, participants were asked if they experienced actual feelings of empathy for the person or people involved. If they responded “yes”, they were subsequently asked to indicate whether they experienced any (or several) of emapthy's subcategories: emotion sharing, perspective taking, and compassion. Subsequently, extent, difficulty, and confidence were probed for every subcategory they indicated. The length of the survey was always the same, irrespective of the answer provided. In the original study, a multitude of questions were asked, which are not relevant for the current research question. For further details see Depow and colleagues63.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using R (Version 4.0.3)95 with RStudio96. We adopted the statistical approach described in Depow and colleagues63 but, additionally examined the effect of age group and interactions with age group on our variables of interest. Age group entered all models as a continuous variable, based on the assumption of ordinality and continuity (e.g.,11,64). Age differences in sample characteristics (compare Table 3) were examined with Chi2-tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables using the R package “stats”95 and “rstatix”97.

Age-differences regarding the different aspects of daily empathy, prosocial behavior, and well-being were analyzed with mixed-effect models, using the mixed function from the “afex” package98. Binary outcomes (experience of empathy (yes/no), engaging in prosocial behavior (yes/no)) were analyzed with generalized mixed-effects models and p-values were calculated with likelihood-ratio tests. Well-being as a continuous outcome (global well-being score resulting from happiness and sense of purpose) was analyzed by using mixed-effects models, with p-values calculated based on the Satterthwaite method98. For each outcome variable, we constructed two models as follows: i) including age as a linear predictor ii) including age both, as a linear and a quadratic predictor. Model selection was conducted based on a loglikelihood ratio test (R function anova). In the results section, the results of the better fitting model are reported, respectively. All models were nested within participant and survey day as random intercepts. In case of convergence warnings, the number of iterations were increased and the optimizer changed to “bobyqa”, followed by reducing the maximum random effect structure by survey day. We controlled for gender, income, religiosity, and education by including them as covariates, each in a separate model. Controlling for these four different covariates did not change the significance level of our predictors of main interest (i.e., age). Thus, in the results section only the models without covariates are reported.

In order to analyze between- and within-subject effects regarding the influence of empathy and age on prosocial behavior and well-being, and prosocial behavior and age on subjective well-being, predictors were centered in different ways. Continuous variables were participant-centered for within-subject effects, and grand-mean centered for between-subject effects. Binary variables were dummy-coded (1 = yes, 0 = no) for within-subject effects and for between-subject effects the grand-mean centered average proportion of yes responses of a participant was used (for further details see63). Model statistics, including effect sizes “r” for fixed effects in mixed-effect models derived from R299 were calculated with the summaryh function from the “hausekeep” package100. The p-adjust function from the “stats” package95 was used to correct p-values for multiple testing with the false discovery procedure101. Data are publicly available at: https://osf.io/y3ud7/, and scripts are publicly available at: https://osf.io/fdmtg/.

Data availability

All data and materials are publicly available at: https://osf.io/y3ud7/, and scripts are publicly available at: https://osf.io/fdmtg/.

Change history

23 August 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40699-0

References

Ishii-Kuntz, M. Social interaction and psychological well-being: comparison across stages of adulthood. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 30, 15–36 (1990).

Steptoe, A., Deaton, A. & Stone, A. A. Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. The Lancet 385, 640–648 (2015).

Batson, C. & Powell, A. Altruism and prosocial behavior. in Handbook of psychology: Personality and social psychology vol. 5 463–484 (John Wiley & Sons, 2003).

Grühn, D., Rebucal, K., Diehl, M., Lumley, M. & Labouvie-Vief, G. Empathy across the adult lifespan: Longitudinal and experience-sampling findings. Emotion 8, 753–765 (2008).

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B. & Layton, J. B. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 7, 20 (2010).

Cacioppo, J. T. & Cacioppo, S. The growing problem of loneliness. The Lancet 391, 426 (2018).

Stietz, J., Jauk, E., Krach, S. & Kanske, P. dissociating empathy from perspective-taking: evidence from intra- and inter-individual differences research. Front. Psychiatry 10, 126 (2019).

Beadle, J. N. & de la Vega, C. E. Impact of aging on empathy: review of psychological and neural mechanisms. Front. Psychiatry 10, 331 (2019).

Reiter, A. M. F., Kanske, P., Eppinger, B. & Li, S.-C. The aging of the social mind - differential effects on components of social understanding. Sci. Rep. 7, 11046 (2017).

Stietz, J. et al. The Aging of the Social Mind: Replicating the preservation of socio-affective and the decline of socio-cognitive processes with age. Accept. R Soc Open Sci (2021).

Sze, J. A., Gyurak, A., Goodkind, M. S. & Levenson, R. W. Greater emotional empathy and prosocial behavior in late life. Emotion 12, 1129–1140 (2012).

Richter, D. & Kunzmann, U. Age differences in three facets of empathy: Performance-based evidence. Psychol. Aging 26, 60–70 (2011).

Bailey, P. E., Brady, B., Ebner, N. C. & Ruffman, T. Effects of age on emotion regulation, emotional empathy, and prosocial behavior. J. Gerontol. Ser. B https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby084 (2018).

Beadle, J. N., Sheehan, A. H., Dahlben, B. & Gutchess, A. H. Aging, empathy, and prosociality. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 70, 213–222 (2015).

Wieck, C. & Kunzmann, U. Age differences in empathy: Multidirectional and context-dependent. Psychol. Aging 30, 407–419 (2015).

Henry, J. D., Phillips, L. H., Ruffman, T. & Bailey, P. E. A meta-analytic review of age differences in theory of mind. Psychol. Aging 28, 826–839 (2013).

Girardi, A., Sala, S. D. & MacPherson, S. E. Theory of mind and the ultimatum game in healthy adult aging. Exp. Aging Res. 44, 246–257 (2018).

Lecce, S., Ceccato, I. & Cavallini, E. Theory of mind, mental state talk and social relationships in aging: The case of friendship. Aging Ment. Health 23, 1105–1112 (2019).

Grainger, S. A., Henry, J. D., Naughtin, C. K., Comino, M. S. & Dux, P. E. Implicit false belief tracking is preserved in late adulthood. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 71, 1980–1987 (2018).

Slessor, G., Phillips, L. H. & Bull, R. Exploring the specificity of age-related differences in theory of mind tasks. Psychol. Aging 22, 639–643 (2007).

O’Brien, E., Konrath, S. H., Gruhn, D. & Hagen, A. L. Empathic concern and perspective taking: linear and quadratic effects of age across the adult life span. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 68, 168–175 (2013).

Phillips, L. H., MacLean, R. D. J. & Allen, R. Age and the understanding of emotions: neuropsychological and sociocognitive perspectives. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 57, P526–P530 (2002).

Schieman, S. & Van Gundy, K. The personal and social links between age and self-reported empathy. Soc. Psychol. Q. 63, 152 (2000).

Bailey, P. E., Ebner, N. C. & Stine-Morrow, E. A. L. Introduction to the special issue on prosociality in adult development and aging: Advancing theory within a multilevel framework. Psychol. Aging 36, 1–9 (2021).

Cutler, J., Nitschke, J. P., Lamm, C. & Lockwood, P. L. Older adults across the globe exhibit increased prosocial behavior but also greater in-group preferences. Nat. Aging 1, 880–888 (2021).

Bailey, P. E., Ruffman, T. & Rendell, P. G. Age-related differences in social economic decision making: the ultimatum game. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 68, 356–363 (2013).

Bailey, P. E., Brady, B., Ebner, N. C. & Ruffman, T. Effects of age on emotion regulation, emotional empathy, and prosocial behavior. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 75, 802–810 (2020).

Charness, G. & Villeval, M.-C. Cooperation, Competition, and Risk Attitudes: An Intergenerational Field and Laboratory Experiment. (2007).

Lockwood, P. L. et al. Aging increases prosocial motivation for effort. Psychol. Sci. 32, 668–681 (2021).

Freund, A. M. & Blanchard-Fields, F. Age-related differences in altruism across adulthood: Making personal financial gain versus contributing to the public good. Dev. Psychol. 50, 1125–1136 (2014).

Bjälkebring, P., Västfjäll, D., Dickert, S. & Slovic, P. Greater emotional gain from giving in older adults: age-related positivity bias in charitable giving. Front. Psychol. 7, 846 (2016).

Beadle, J. N. et al. Effects of age-related differences in empathy on social economic decision-making. Int. Psychogeriatr. 24, 822–833 (2012).

Roalf, D. R., Mitchell, S. H., Harbaugh, W. T. & Janowsky, J. S. Risk, reward, and economic decision making in aging. J. Gerontol. Ser. B-Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 67, 289–298 (2012).

Cavallini, E., Rosi, A., Ceccato, I., Ronchi, L. & Lecce, S. Prosociality in aging: The contribution of traits and empathic concern. Personal. Individ. Differ. 176, 110735 (2021).

Bruine de Bruin, W. & Ulqinaku, A. Effect of mortality salience on charitable donations: Evidence from a national sample. Psychol. Aging (2020) doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000478.

Borges, A. P., Reis, A. & Anjos, J. Willingness to pay for other individuals’ healthcare expenditures. Public Health 144, 64–69 (2017).

Batson, C. D. Empathy-induced altruistic motivation. in Prosocial motives, emotions, and behavior: The better angels of our nature. (eds. Mikulincer, M. & Shaver, P. R.) 15–34 (American Psychological Association, 2010). https://doi.org/10.1037/12061-001.

Davis, M. H. Empathy and Prosocial Behavior. The Oxford Handbook of Prosocial Behavior https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195399813.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780195399813-e-026 (2015).

Eisenberg, N. & Miller, P. A. The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors. Psychol. Bull. 101, 91–119 (1987).

Telle, N.-T. & Pfister, H.-R. Positive empathy and prosocial behavior: A neglected link. Emot. Rev. 8, 154–163 (2016).

Kunzmann, U., Little, T. D. & Smith, J. Is age-related stability of subjective well-being a paradox? Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence from the Berlin Aging Study. Psychol. Aging 15, 511–526 (2000).

Hicks, J. A., Trent, J., Davis, W. E. & King, L. A. Positive affect, meaning in life, and future time perspective: An application of socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychol. Aging 27, 181–189 (2012).

Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M. & Charles, S. T. Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional se- lectivity theory. Am. Psychol. 54, 165–181 (1999).

Charles, S. T. & Carstensen, L. L. Social and emotional aging. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 61, 383–409 (2010).

Ziaei, M., von Hippel, W., Henry, J. D. & Becker, S. I. Are Age Effects in Positivity Influenced by the Valence of Distractors? PLOS ONE 10, e0137604 (2015).

Mather, M. & Carstensen, L. L. Aging and motivated cognition: the positivity effect in attention and memory. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9, 496–502 (2005).

Erbey, M. et al. Positivity in Younger and in Older Age: Associations With future time perspective and socioemotional functioning. Front. Psychol. 11, 567133 (2020).

Ziaei, M., Salami, A. & Persson, J. Age-related alterations in functional connectivity patterns during working memory encoding of emotional items. Neuropsychologia 94, 1–12 (2017).

Grühn, D., Smith, J. & Baltes, P. B. No aging bias favoring memory for positive material: Evidence from a heterogeneity-homogeneity list paradigm using emotionally toned words. Psychol. Aging 20, 579–588 (2005).

Orben, A., Lucas, R. E., Fuhrmann, D. & Kievit, R. Trajectories of adolescent life satisfaction. (2020).

Frijters, P. & Beatton, T. The mystery of the U-shaped relationship between happiness and age. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 82, 525–542 (2012).

Stone, A. A., Schwartz, J. E., Broderick, J. E. & Deaton, A. A snapshot of the age distribution of psychological well-being in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 9985–9990 (2010).

Carstensen, L. L., Mayr, U., Pasupathi, M. & Nesselroade, J. R. Emotional Experience in Everyday Life Across the Adult Life Span. 12 (2000).

Galambos, N. L., Krahn, H. J., Johnson, M. D. & Lachman, M. E. The U shape of happiness across the life course: Expanding the discussion. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 15, 898–912 (2020).

Laaksonen, S. A research note: happiness by age is more complex than U-shaped. J. Happiness Stud. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9830-1 (2016).

Li, N. Multidimensionality of longitudinal data: unlocking the age-happiness puzzle. Soc. Indic. Res. 128, 305–320 (2016).

Chi, K., Almeida, D. M., Charles, S. T. & Sin, N. L. Daily prosocial activities and well-being: Age moderation in two national studies. Psychol. Aging 36, 83–95 (2021).

Van Willigen, M. differential benefits of volunteering across the life course. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 55, S308–S318 (2000).

Handbook of research methods for studying daily life. xxvii, 676 (The Guilford Press, 2012).

Neubauer, A. B., Scott, S. B., Sliwinski, M. J. & Smyth, J. M. How was your day? Convergence of aggregated momentary and retrospective end-of-day affect ratings across the adult life span. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 119, 185–203 (2020).

Bielak, A. A. M., Cherbuin, N., Bunce, D. & Anstey, K. J. Intraindividual variability is a fundamental phenomenon of aging: Evidence from an 8-year longitudinal study across young, middle, and older adulthood. Dev. Psychol. 50, 143–151 (2014).

Nezlek, J. B., Feist, G. J., Wilson, F. C. & Plesko, R. M. Day-to-day variability in empathy as a function of daily events and mood. J. Res. Personal. 35, 401–423 (2001).

Depow, G. J., Francis, Z. & Inzlicht, M. The Experience of Empathy in Everyday Life. Psychol. Sci. 16 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797621995202.

Hastie, T. J., Botha, J. L. & Schnitzler, C. M. Regression with an ordered categorical response. Stat. Med. 8, 785–794 (1989).

McAdams, D. P. & Olson, B. D. Personality development: continuity and change over the life course. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 61, 517–542 (2010).

Wojciechowska, L. Subjectivity and generativity in midlife. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 48, 38–43 (2017).

Hall, J. A. & Schwartz, R. Empathy present and future. J. Soc. Psychol. 159, 225–243 (2019).

Kelley. Interpretation of educational measurements/by Truman Lee Kelley. 394 (1927).

Marsh, H. W. Sport motivation orientations: Beware of jingle-jangle fallacies. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 16, 365–380 (1994).

Kanske, P., Böckler, A., Trautwein, F.-M. & Singer, T. Dissecting the social brain: Introducing the EmpaToM to reveal distinct neural networks and brain–behavior relations for empathy and Theory of Mind. Neuroimage 122, 6–19 (2015).

Ziaei, M., Oestreich, L., Reutens, D. C. & Ebner, N. C. Age-related differences in negative cognitive empathy but similarities in positive affective empathy. Brain Struct. Funct. 226, 1823–1840 (2021).

Klimecki, O. M., Leiberg, S., Ricard, M. & Singer, T. Differential pattern of functional brain plasticity after compassion and empathy training. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 9, 873–879 (2014).

Bailey, P. E., Brady, B., Ebner, N. C. & Ruffman, T. Effects of age on emotion regulation, emotional empathy, and prosocial behavior. J. Gerontol. Ser. B https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby084 (2020).

Gaesser, B., Dodds, H. & Schacter, D. L. Effects of aging on the relation between episodic simulation and prosocial intentions. Mem. Hove Engl. 25, 1272–1278 (2017).

Gibson, K. L., McKelvie, S. J. & de Man, A. F. Personality and culture: A comparison of francophones and anglophones in Québec. J. Soc. Psychol. 148, 133–165 (2008).

Li, T. & Siu, P.-M. Socioeconomic status moderates age differences in empathic concern. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbz079 (2019).

PhilippeRushton, J., Fulker, D. W., Neale, M. C., Nias, D. K. B. & Eysenck, H. J. Ageing and the relation of aggression, altruism and assertiveness scales to the Eysenck personality questionnaire. Personal. Individ. Differ. 10, 261–263 (1989).

Shiffman, S., Stone, A. A. & Hufford, M. R. ecological momentary assessment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 4, 1–32 (2008).

Dolan, P., Kudrna, L. & Stone, A. The measure matters: An investigation of evaluative and experience-based measures of wellbeing in time use data. Soc. Indic. Res. 134, 57–73 (2017).

Lelkes, O. Happiness Across the Life Cycle: Exploring Age-Specific Preferences. 17 (2008).

Böckler, A., Tusche, A. & Singer, T. The structure of human prosociality: Differentiating altruistically motivated, norm motivated, strategically motivated, and self-reported prosocial behavior. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 7, 530–541 (2016).

Franzen, A. & Pointner, S. The external validity of giving in the dictator game: A field experiment using the misdirected letter technique. Exp. Econ. 16, 155–169 (2013).

Peysakhovich, A., Nowak, M. A. & Rand, D. G. Humans display a ‘cooperative phenotype’ that is domain general and temporally stable. Nat. Commun. 5, 4939 (2014).

Winking, J. & Mizer, N. Natural-field dictator game shows no altruistic giving. Evol. Hum. Behav. 34, 288–293 (2013).

Bradley, A., Lawrence, C. & Ferguson, E. Does observability affect prosociality?. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 285, 20180116 (2018).

Ferguson, A. M., Cameron, C. D. & Inzlicht, M. Motivational effects on empathic choices. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 90, 104010 (2020).

Zhang, X., Fung, H. H., Stanley, J. T., Isaacowitz, D. M. & Ho, M. Y. Perspective taking in older age revisited: A motivational perspective. Dev. Psychol. 49, 1848–1858 (2013).

Zhang, X. et al. Plasticity in older adults’ theory of mind performance: the impact of motivation. Aging Ment. Health 22, 1592–1599 (2018).

Reiter, A. M. F., Diaconescu, A. O., Eppinger, B. & Li, S.-C. Human aging alters social inference about others’ changing intentions. Neurobiol. Aging 103, 98–108 (2021).

Carpenter, J., Connolly, C. & Myers, C. K. Altruistic behavior in a representative dictator experiment. Exp. Econ. 11, 282–298 (2008).

Chen, Y.-C., Chen, C.-C., Decety, J. & Cheng, Y. Aging is associated with changes in the neural circuits underlying empathy. Neurobiol. Aging 35, 827–836 (2014).

Hildebrandt, M. K., Jauk, E., Lehmann, K., Maliske, L. & Kanske, P. Brain activation during social cognition predicts everyday perspective-taking: A combined fMRI and ecological momentary assessment study of the social brain. NeuroImage 227, 117624 (2021).

Grosse Rueschkamp, J. M., Brose, A., Villringer, A. & Gaebler, M. Neural correlates of up-regulating positive emotions in fMRI and their link to affect in daily life. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 14, 1049–1059 (2019).

Gadassi, P. et al. Better together: A systematic review of studies combining Magnetic Resonance Imaging with Ecological Momentary Assessment. (2021) https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/mxznb.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020).

RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R. (RStudio, PBC, 2020).

Kassambara, A. rstatix: Pipe-Friendly Framework for Basic Statistical Tests. (2021).

Singmann, H., Bolker, B., Westfall, J., Aust, F. & Ben-Shachar, M. S. afex:Analysis of Factorial Experiments. (2021).

Edwards, L. J., Muller, K. E., Wolfinger, R. D., Qaqish, B. F. & Schabenberger, O. An R2 statistic for fixed effects in the linear mixed model. Stat. Med. 27, 6137–6157 (2008).

Lin, H. hausekeep: Miscellaneous helper and utility functions. (2019).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 57, 289–300 (1995).

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG RE 4449/1-1, KA 4412/2-1, LI879/22-1) and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (#435-2019-0144). AMFR acknowledges further support by grants from the German Research Foundation (DFG) (SFB 940/3 B7 RTG 2660/B2) and by a 2020 NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation. We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Funds of the SLUB Dresden.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.P., and A.M.F.R. conceived the study. G.J.D., and M.I. developed the survey and collected data. L.P. and A.M.F.R. analyzed the data., L.P., J.S., P.K., and S.-C. L. and A.M.F.R. interpreted the data. L.P. wrote the manuscript. All authors provided critical revisions and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors, where Table 4 was incomplete. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pollerhoff, L., Stietz, J., Depow, G.J. et al. Investigating adult age differences in real-life empathy, prosociality, and well-being using experience sampling. Sci Rep 12, 3450 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06620-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06620-x

This article is cited by

-

Empathy and Autism: Establishing the Structure and Different Manifestations of Empathy in Autistic Individuals Using the Perth Empathy Scale

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2024)

-

Cognitive effort for self, strangers, and charities

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.