Abstract

Treatment recommendations for fragility fractures of the pelvis (FFP) have been provided along with the good reliable FFP classification but they are not proven in large studies and recent reports challenge these recommendations. Thus, we aimed to determine the usefulness of the FFP classification determining the treatment strategy and favored procedures in six level 1 trauma centers. Sixty cases of FFP were evaluated by six experienced pelvic surgeons, six inexperienced surgeons in training, and one surgeon trained by the originator of the FFP classification during three repeating sessions using computed tomography scans with multiplanar reconstruction. The intra-rater reliability and inter-rater reliability for therapeutic decisions (non-operative treatment vs. operative treatment) were moderate, with Fleiss kappa coefficients of 0.54 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.44–0.62) and 0.42 (95% CI 0.34–0.49). We found a therapeutic disagreement predominantly for FFP II related to a preferred operative therapy for FFP II. Operative treated cases were generally treated with an anterior–posterior fixation. Despite the consensus on an anterior–posterior fixation, the chosen procedures are highly variable and most plausible based on the surgeon’s preference.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

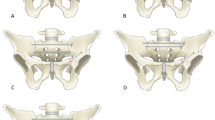

Fragility fractures of the pelvis have increased in recent years, accompanied by the loss of mobility and autonomy, with increased rates of mortality1,2,3,4,5. Variable morphology, dynamic fracture progression, and the resulting instability have led to the development of a computed tomography (CT)-based FFP classification6 (Fig. 1) which is as reliable as the OTA/Tile and Young and Burgess classifications7,8.

Fragility fracture of the pelvis (FFP) classification. The FFP classification is outlined according to the characteristic fracture morphology. The main lesions are in red and the less common lesions are in orange. Non-operative treatment is recommended for FFP I and FFP II. Operative stabilization is recommended for FFP III and FFP IV. FFP II with prolonged pain or restricted mobilization should be considered for operative treatment as well.

Based on the classification the following recommendations were given, non-operative treatment for FFP I; non-operative or operative treatment, depending on the patient’s mobility, for FFP II; and operative treatment for FFP III and FFP IV9.

However, recent monocentric studies challenged the recommendations of Rommens and Hofmann6 and showed good results for operatively treated FFP II10,11,12,13 and non-operatively treated FFP III and FFP IV14,15.

This brings into question the usefulness of the FFP classification and the accompanying treatment recommendations.

Currently, there is a lack of data on the usefulness of the FFP classification for therapeutic decision-making, even though this data is essential for preventing harm that could occur due to inappropriate classification of the fracture categories that may lead to incorrect treatment decisions16.

Therefore, in the present study we used CT with multiplanar reconstruction, without clinical information and assessed the intra-rater reliability and inter-rater reliability of therapeutic decision-making for FFP (non-operative vs. operative treatment). We investigated the treatment recommendations, their relation to the FFP classification6 and the effects of classification disagreement on treatment decisions.

Using this approach, we aimed to determine the reliability of treatment strategies derived from CT scans and resulting FFP classification, and thus the usefulness of FFP classification in relation to clinically relevant decisions (operative vs. non-operative). Furthermore, we investigated the favored operative procedures in relation to the FFP classification.

Methods

Study design

The study design used to evaluate the FFP classification, sample size calculation, patient demographics, anonymization, and rating procedures was reported by Pieroh et al.8 The patients from this study8 were used to analyze the association between the FFP classification and the resulting treatment decision as well as the favored operative procedure. Each observer was familiar with the FFP classification and no additional training was performed before the study. At least two weeks lay between the classification cycles and observers had no access to the previous ratings and classification cycles.

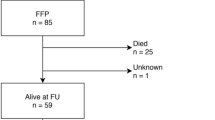

In addition to classification, recommended treatment options are also presented in Fig. 2.

Treatment decisions for FFP. At first, the rater had to decide between non-operative and operative treatment. No further specific treatment data were obtained when non-operative treatment was performed. For operative treatment, the rater had to decide whether to use anterior and/or posterior stabilization. For anterior stabilization, the rater could choose between procedures; no combinations were possible. For posterior stabilization, the rater could choose unilateral or bilateral stabilization and further specified the operative method; combinations were possible.

Statistical analyses

Intra-rater reliability and Inter-rater reliability

We assessed the intra-rater reliability and inter-rater reliability of the therapeutic decisions (non-operative vs. operative) as previously reported8 using specific MATLAB scripts (MATLAB, version 2013b; MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) to calculate the Fleiss kappa coefficients17,18 and presented them as means and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The 95% CI was generated using the bootstrap method of resampling the pelves17,18.

Treatment decisions were collected during the classification process from each of the 6 experienced and inexperienced surgeons and the surgeon trained by the creator of the FFP classification (“gold standard”), all from Level-1 trauma centers8. Inexperienced raters were included as part of this pragmatic multicenter agreement study to assess the generalizability of the classification related decisions in raters with differing experience16.

The “gold standard” was included due to his adherence to the prescribed treatment recommendations6. We generated the intra-rater reliability based on the three classification cycles, separate for each rater. For the inter-rater reliability, we calculated one mean vote for each rater out of the three classification cycles and used this for further analysis. Using this data, we determined the inter-rater reliability for each classification cycle and for the overall cycles.

We graded the intra-rater reliability and inter-rater reliability using the following categories determined by Landis and Koch19: Fleiss kappa coefficient of 1, perfect reliability; ≥ 0.81, almost perfect reliability; 0.61–0.80, substantial reliability; 0.41–0.60, moderate reliability; 0.2–0.40, fair reliability; and ≤ 0.21, poor reliability.

Agreement analyses

We used the classifications and therapeutic decisions determined by the references, “gold standard”, submitting hospitals, and majority vote. We investigated the agreement between the therapeutic decisions of the raters and the therapeutic decisions indicated by the references for FFP. We generated the majority vote, similar to the mean vote, for calculating the inter-rater reliability and included the gold standard and submitting hospital votes.

Classification and therapeutic decision agreement

Case 48 was excluded because its FFP classification was not possible according to the gold standard and 42.9% of raters8. We generated the majority vote based on the rater votes for the classification and therapeutic decision for each case (n = 59). The gold standard and submitting hospital votes were excluded from this vote. Using the therapeutic decision of that majority vote, we separated cases according to the recommended non-operative and operative treatments. Subsequently, we allocated cases to the FFP classification based on the gold standard classification. We examined the agreement and disagreement (“gold standard” vs. raters) between the classification and therapeutic decision for each case to assess the impact of classification disagreement on the therapeutic decision.

Preferred operative therapy

Cases where operative therapy was recommended, were analyzed to assess the operative therapy (Fig. 2) preferred by all the raters, the gold standard, and the submitting hospital. Raters had to choose an anterior procedure. For posterior stabilization, unilateral or bilateral procedures could be chosen. The available procedures could be combined.

Ethical statement and study registration

The following ethics committees approved the study: Ethics Commission at the Medical Faculty of the University of Leipzig, Universitäts Klinikum Jena Ethics Commission, Ethics Committee Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Ethics Commission Medical Association of Saarland, Ethics Committee at the Medical Faculty of the Eberhard Karls University and at the University Hospital Tübingen, Ethics Committee of the University of Ulm.

All these mentioned ethics committees waived the need for informed consent of the patients for this study due to the retrospective nature of the study and because patients consented to the use of de-identified CT scans for research on signing the hospital contract of admission. Separate informed consent was not obtained since the data was collected retrospectively. Afterwards, the study was registered in the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00014248). CT scans with multiplanar reconstruction were performed for clinical reasons. The study was performed in accordance to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Classifications and treatment decisions based on the gold standard, submitting hospital, and majority vote for each patient, are summarized in Supplementary Table S1. The patient demographics are available in Appendix II of Pieroh et al.8.

Intra- and Inter-rater reliability

The gold standard and both raters of hospital 1 had almost perfect intra-rater reliability (Table 1). The decisions of two experienced and three inexperienced raters had substantial intra-rater reliability. The overall intra-rater reliability (Table 1), overall inter-rater reliability and inter-rater reliability of the experienced raters were moderate (Table 2). The overall inter- rater reliability of the decisions of the inexperienced raters was fair (Table 2).

Agreement analyses

The highest therapeutic agreement (> 90%) was found for FFP I and the lowest was found for FFP II (minimum compared to the gold standard, 66.0%) (Table 3). For FFP I and FFP II, the majority voted for non-operative therapy (Table 3). The agreement for FFP III and FFP IV was > 75%, and the majority recommended operative treatment.

Classification and therapeutic decision agreement

For FFP I, FFP III, and FFP IV, the classifications and resulting treatment decisions were majorly in agreement (Table 4). Pronounced disagreement regarding therapy was found for FFP II, both in classification and treatment recommendation. Although the raters and gold standard agreed on the classification of one FFP IIb case and four FFP IIc cases, the raters recommended surgery (Fig. 3).

FFP II cases with classification agreement but differences in treatment recommendations. One FFP IIb case (non-displaced fracture of the sacral ala; anterior fracture not shown) was recommended to undergo non-operative treatment by the gold standard, submitting hospital, and raters. A bilateral non-displaced fracture of the sacral ala without horizontal communication (FFP IIb) was recommended to undergo operative treatment by the raters only. A unilateral, multi-fragmentary, non-displaced fracture of the sacral ala (FFP IIc) was recommended to undergo surgery by the raters and the submitting hospital. Fracture lines are indicated by white arrows.

Surgical treatment preferences

One FFP IIc case (case 39) was excluded from further analyses because < 50% recommended anterior stabilization and/or posterior stabilization. The FFP classification, agreement regarding anterior stabilization and unilateral or bilateral stabilization, and the procedure frequencies are summarized in Supplementary Table S2. Anterior stabilization was recommended for 18 cases (Table 5, Supplementary Table S2). The external fixator was the favored anterior procedure. Posterior instrumentation was recommended for all cases with surgical stabilization. Bilateral fixation was recommended for FFP IIa, FFP IIb, FFP IIIb, and FFP IV cases, which corresponded to 58% (n = 17) of all cases recommended for surgery (Table 5).

Unilateral stabilization was predominantly recommended for FFP IIc, FFP IIIa, and FFP IIIc. For sacral fractures (FFP II and FFP IIIc), the raters preferred stabilization with sacroiliac screws/transsacral bar or, as second choice, with a trans-iliac fixator or spinopelvic fixation. Transiliac fractures (FFP IIIa) were treated with an iliac plate through the lateral window using the ilioinguinal approach. Sacroiliac screws/transsacral bar and an iliac plate were recommended for the FFP IIIb case. Half of the FFP IVb cases were recommended to undergo treatment with sacroiliac screws/transsacral bar, and the other half of the FFP IVb cases were recommended to undergo spinopelvic fixation (Fig. 4). For FFP IVb, if sacroiliac screws/transsacral bar fixation was chosen, then the second choice was spinopelvic fixation, and vice versa.

FFP IVb examples with differing recommended posterior operative stabilization methods. Approximately half of the raters recommended that the presented fractures required sacroiliac screws (SIS) or spinopelvic fixation (SPF) (maximum rating difference, 2 votes). The fracture recommended for SIS was a bilateral non-displaced fracture of the sacral ala with vertical communication below S2 and minimal anterior displacement. The fractures recommended for SPF were a displaced trans-foraminal fracture (Denis zone II), a non-displaced fracture of the sacral ala, and a central fracture through S1. In the sagittal view, the vertical fracture through S1 without anterior or posterior displacement is revealed.

Anterior and posterior, percutaneous procedures were the preferred choice for operatively treating FFP.

Discussion

The surgeons agreed to treat isolated anterior lesions (FFP I) non-operatively and to recommend operative treatment for posteriorly displaced fractures (FFP III and FFP IV). There was some disagreement regarding the therapeutic decisions for non-displaced posterior fractures (FFP II). For cases with indications for operative treatment, a combination of anterior and posterior surgery was recommended.

Classification systems should distinguish patients receiving non-operative or operative treatment. Despite a high reported agreement in treating LC-1 fractures/Tile B fractures20 (comparable to FFP II)—representing the most common fracture type in the elderly21—the disagreement found in the survey analysis of Beckmann et al.22 highlights the differing treatment for a similar fracture type. To improve the treatment, the examination under anesthesia (EUA) for lateral compression fractures was introduced, but their interpretation shows a relevant disagreement23. Furthermore, the deduced treatment and the consensus might change upon newer data24,25,26.

The moderate intra-rater reliability and inter-rater reliability for therapeutic decisions observed during our study might be the result of still conflicting information about mortality after non-operative or operative treatment for FFP, and some evidence of lower mortality for operated cases8,27,28. Here, we would like to emphasize that the grading was done using the arbitrarily, not proven but widely used benchmarks according to Landis and Koch29. Using the stricter and probably more practical29 but also arbitrarily set ranges of Svanholm et al.30 would lead to good intra-rater reliabilities for all raters but only good inter-rater reliabilities for experienced observers. The missing validation of these criteria should be considered weighting the presented Fleiss kappa values.

The inexperienced raters presented only a fair inter-rater reliability. One reason might their missing experience in treating pelvic ring injuries by their own. However, in our view most probably, the differences result from classification differences especially between non-displaced and displaced posterior pelvic ring lesions (FFP II vs. FFP III) and the missing detection of the horizontal connection of bilateral sacral lesion leading to a difference in treatment from non-operative to operative treatment.

Therapeutic decisions for FFP based on morphology or classification have not yet been studied, although fracture severity (Tile A vs. B) influenced the survival after FFP31. Similar to a survey analysis on the treatment of high-energy pelvic fractures, we determined a high agreement for stable (Tile A—FFP I) and completely unstable fractures (Tile C—FFP III, FFP IV) but a low agreement for partially stable injuries (Tile B—FFP II)20.

Our study showed a consensus for the treatment of FFP I, FFP III, and FFP IV by applying the consensus criteria (agreement ≥ 75%) for Delphi studies32. The therapeutic strategy chosen by the raters generally followed the recommendations of Rommens and Hofmann6,33. Fractures classified as FFP II showed the lowest agreement for the treatment strategy, probably because of the impaired differentiation between FFP II and FFP III8. However, the classification disagreement itself was not responsible for the differences in therapeutic decisions for FFP. The observers tended to recommend operative treatment for FFP II more often, probably due to the successful operative treatment of these injuries in terms of preserved autonomy, lower mortality3, and to hasten pain relief10,11,12,34. Furthermore, even incomplete, simple sacral fractures (FFP II) displace in approximately 30% of elderly patients to FFP III or FFP IV, especially in patients treated non-operatively, leading to a secondary operative procedure35. Even after 6 months of failed non-operative therapy, patients with FFP II benefited from operative therapy10. However, late surgical therapies might be complicated by deformities in contrast to early performed percutaneous procedures6,36.

Thus, a close follow-up especially for non-operatively treated cases is necessary. Additional factors such as general health21 and a radiographic rating system37 may help with decision-making, especially for FFP II.

Although our study indicated equal use of spinopelvic fixation6 and sacroiliac screws/transsacral implant fixation38,39 for posterior bilateral displaced sacral fractures (FFP IVb), discriminating radiological factors were not found. Significant pain reduction without complications after operative treatment using percutaneous transiliac-transsacral screws or bilateral sacroiliac screws in the upper sacral segment has been reported38,40,41. Interestingly, even unilateral injuries were recommended bilateral stabilization, probably to avoid fracture progression35,42.

The external fixator was preferred for the anterior ring, by four of the seven hospitals. The external pelvic fixator has been reported as a valuable tool for the elderly43, but it may be complicated by frequent loosening or pin tract infections44,45. Retrograde transpubic screw fixation has yielded good results in terms of fracture reduction and healing, with only a small number of adverse events (17 of 128 cases) reported by a large retrospective series46. Anterior plate osteosynthesis is complicated by loosening and consecutive non-union as well as excessive blood loss in elderly patients47,48. It should be noted that two hospitals and the gold standard preferred retrograde pubic screws whereas four hospitals preferred the external fixator.

Currently, it remains unclear which patients require anterior stabilization. A recent systematic review highlights the low number of cases treated anteriorly but also emphasizes the low quality of studies49. However, comparing all three anterior stabilization procedures, all of them showed a relevant complication rate, a maximum of one quarter of patients required revision surgery46,47,50. The need for anterior stabilization as well as the type of osteosynthesis should be investigated in prospective studies.

Clinical data regarding mobility, pain, perioperative risks, and expectations, especially for patients with FFP II is needed to make appropriate treatment decisions. The influences of these factors on the patient’s prognosis need to be elaborated21.

Besides, an incorrect classification of FFP II by the observer, the observer might decide to not follow the recommendations of Rommens and Hofmann9. This might be the result of current studies showing a decreased rate of mortality51, rate of general complications for percutaneous procedures52 and an improved mobility following operative therapy53. This data underlines the need to introduce additional modifiers for treatment decision (e.g. previous mobility level, pain level) and probably of a progressive operative treatment to avoid immobility-associated complications54. On the other hand, data from Saito et al. challenge the more progressive operative treatment55. Based upon the ongoing data gain, an adaption of the recommendations should be considered.

Non-operative therapy should be standardized and the time to failure of non-operative therapy should be defined to avoid immobility-associated complications such as pressure ulcera54.

The FFP classification has sufficient intra-rater and inter-rater reliability however the choice of fixation among the options available especially in the posterior ring injuries are somewhat unclear and depend more on the physician's experience and training.

Although we determined a high agreement of the raters to the proposed therapy by the FFP classification, the clinical course and success in patients must be proven.

The FFP classification might become useful for guiding non-operative and operative therapy strategies, but the inclusion of non-radiological data and recent studies is required to improve therapy guidance. Recommendations for treating FFP have not yet been finalized and controversy exists, especially concerning FFP II. Here, additional factors e.g. secondary displacement and/or unrelenting pain on ambulation should be considered in the change from non-operative treatment to operative treatment in patients with FFP II.

Most differences in procedure were observed due to the individual preference of a surgeon and missing evidence in terms of comparative studies. Based on these findings, the relevance of the FFP classification criteria, operative procedures, and their outcomes should be evaluated further. Here, the patients suffering from a FFP II requiring operative treatment, the concept for non-operative therapy, the most non-invasive type of stabilization with the required stability, fractures at risk for fracture progression as well as the patients requiring anterior fixation should be identified.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Andrich, S. et al. Epidemiology of pelvic fractures in Germany: Considerably high incidence rates among older people. PLoS One 10, e0139078. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139078 (2015).

Andrich, S. et al. Excess mortality after pelvic fractures among older people. J. Bone Miner. Res. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3116 (2017).

Maier, G. S. et al. Risk factors for pelvic insufficiency fractures and outcome after conservative therapy. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 67, 80–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2016.06.020 (2016).

Marrinan, S., Pearce, M. S., Jiang, X. Y., Waters, S. & Shanshal, Y. Admission for osteoporotic pelvic fractures and predictors of length of hospital stay, mortality and loss of independence. Age Ageing 44, 258–261. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afu123 (2015).

Nanninga, G. L., de Leur, K., Panneman, M. J. M., van der Elst, M. & Hartholt, K. A. Increasing rates of pelvic fractures among older adults: The Netherlands, 1986–2011. Age Ageing 43, 648–653. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/aft212 (2014).

Rommens, P. M. & Hofmann, A. Comprehensive classification of fragility fractures of the pelvic ring: Recommendations for surgical treatment. Injury 44, 1733–1744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2013.06.023 (2013).

Berger-Groch, J. et al. The intra- and interobserver reliability of the Tile AO, the Young and Burgess, and FFP classifications in pelvic trauma. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 139, 645–650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-019-03123-9 (2019).

Pieroh, P. et al. Fragility fractures of the pelvis classification: A multicenter assessment of the intra-rater and inter-rater reliabilities and percentage of agreement. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 101, 987–994. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.18.00930 (2019).

Rommens, P. M., Wagner, D. & Hofmann, A. Fragility fractures of the pelvis. JBJS Rev. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.RVW.16.00057 (2017).

Arduini, M., Saturnino, L., Piperno, A., Iundusi, R. & Tarantino, U. Fragility fractures of the pelvis: Treatment and preliminary results. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 27(Suppl 1), S61–S67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-015-0430-4 (2015).

Schmitz, P. et al. Clinical application of a minimally invasive cement-augmentable Schanz screw rod system to treat pelvic ring fractures. Int. Orthop. 43, 697–703. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-018-3988-6 (2019).

Eckardt, H. et al. Good functional outcome in patients suffering fragility fractures of the pelvis treated with percutaneous screw stabilisation: Assessment of complications and factors influencing failure. Injury 48, 2717–2723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2017.11.002 (2017).

Noser, J. et al. Mid-term follow-up after surgical treatment of fragility fractures of the pelvis. Injury 49, 2032–2035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2018.09.017 (2018).

Kanakaris, N. K., Greven, T., West, R. M., van Vugt, A. B. & Giannoudis, P. V. Implementation of a standardized protocol to manage elderly patients with low energy pelvic fractures: Can service improvement be expected?. Int. Orthop. 41, 1813–1824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-017-3567-2 (2017).

Yoshida, M. et al. Mobility and mortality of 340 patients with fragility fracture of the pelvis. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-020-01481-3 (2020).

Audigé, L., Bhandari, M., Hanson, B. & Kellam, J. A concept for the validation of fracture classifications. J. Orthop. Trauma 19, 401–406. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.bot.0000155310.04886.37 (2005).

Fleiss, J. L. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol. Bull. 76, 378–382. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0031619 (1971).

Falotico, R. & Quatto, P. Fleiss’ kappa statistic without paradoxes. Qual. Quant. 49, 463–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-014-0003-1 (2015).

Landis, J. R. & Koch, G. G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33, 159–174 (1977).

Furey, A. J. et al. Surgeon variability in the treatment of pelvic ring injuries. Orthopedics 33, 714. https://doi.org/10.3928/01477447-20100826-14 (2010).

Höch, A. et al. Age and “general health”-beside fracture classification-affect the therapeutic decision for geriatric pelvic ring fractures: A German pelvic injury register study. Int. Orthop. 43, 2629–2636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-019-04326-w (2019).

Beckmann, J. T. et al. Operative agreement on lateral compression-1 pelvis fractures a survey of 111 OTA members. J. Orthop. Trauma 28, 681–685. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000000133 (2014).

Carney, J. J., Nguyen, A., Alluri, R. K., Lee, A. K. & Marecek, G. S. A survey to assess agreement between pelvic surgeons on the outcome of examination under anesthesia for lateral compression pelvic fractures. J. Orthop. Trauma 34, e304–e308. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000001759 (2020).

Tornetta, P. et al. Does operative intervention provide early pain relief for patients with unilateral sacral fractures and minimal or no displacement?. J. Orthop. Trauma 33, 614–618. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000001578 (2019).

Vallier, H. A. et al. Surgery for unilateral sacral fractures: Are the indications clear?. J. Orthop. Trauma 33, 619–625. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000001587 (2019).

Slobogean, G. P. et al. A prospective clinical trial comparing surgical fixation versus nonoperative management of minimally displaced complete lateral compression pelvis fractures. J. Orthop. Trauma https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000002088 (2021).

Höch, A., Özkurtul, O., Pieroh, P., Josten, C. & Böhme, J. Outcome and 2-year survival rate in elderly patients with lateral compression fractures of the pelvis. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 8, 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2151458516681142 (2017).

Osterhoff, G. et al. Early operative versus nonoperative treatment of fragility fractures of the pelvis: A propensity-matched multicenter study. J. Orthop. Trauma 33, e410–e415. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000001584 (2019).

Garbuz, D. S., Masri, B. A., Esdaile, J. & Duncan, C. P. Classification systems in orthopaedics. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 10, 290–297. https://doi.org/10.5435/00124635-200207000-00007 (2002).

Svanholm, H. et al. Reproducibility of histomorphologic diagnoses with special reference to the kappa statistic. APMIS Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. Scand. 97, 689–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1699-0463.1989.tb00464.x (1989).

Petryla, G. et al. The one-year mortality rate in elderly patients with osteoporotic fractures of the pelvis. Arch. Osteoporos. 15, 15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-020-0689-8 (2020).

Diamond, I. R. et al. Defining consensus: A systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 67, 401–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002 (2014).

Rommens, P. M. et al. Isolated pubic ramus fractures are serious adverse events for elderly persons: An observational study on 138 patients with fragility fractures of the pelvis Type I (FFP Type I). J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9082498 (2020).

Wagner, D., Ossendorf, C., Gruszka, D., Hofmann, A. & Rommens, P. M. Fragility fractures of the sacrum: How to identify and when to treat surgically?. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 41, 349–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-015-0530-z (2015).

Rommens, P. M. et al. Progress of instability in fragility fractures of the pelvis: An observational study. Injury 50, 1966–1973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2019.08.038 (2019).

Mears, D. C. & Velyvis, J. Surgical reconstruction of late pelvic post-traumatic nonunion and malalignment. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 85, 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.85b1.13349 (2003).

Beckmann, J. et al. Validated radiographic scoring system for lateral compression type 1 pelvis fractures. J. Orthop. Trauma 34, 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000001639 (2020).

Pulley, B. R., Cotman, S. B. & Fowler, T. T. Surgical fixation of geriatric sacral U-type insufficiency fractures: A retrospective analysis. J. Orthop. Trauma 32, 617–622. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000001308 (2018).

Wagner, D. et al. Trans-sacral bar osteosynthesis provides low mortality and high mobility in patients with fragility fractures of the pelvis. Sci. Rep. 11, 14201. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93559-0 (2021).

Walker, J. B., Mitchell, S. M., Karr, S. D., Lowe, J. A. & Jones, C. B. Percutaneous transiliac-transsacral screw fixation of sacral fragility fractures improves pain, ambulation, and rate of disposition to home. J. Orthop. Trauma 32, 452–456. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000001243 (2018).

Mendel, T. et al. Mid-term outcome of bilateral fragility fractures of the sacrum after bisegmental transsacral stabilization versus spinopelvic fixation. Bone Jt. J. 103-B, 462–468. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.103B3.BJJ-2020-1454.R1 (2021).

Mendel, T. et al. Progressive instability of bilateral sacral fragility fractures in osteoporotic bone: A retrospective analysis of X-ray, CT, and MRI datasets from 78 cases. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-020-01480-4 (2020).

Gänsslen, A., Hildebrand, F. & Kretek, C. Supraacetabular external fixation for pain control in geriatric type B pelvic injuries. Acta Chir. Orthop. Traumatol. Cech. 80, 101–105 (2013).

Wardle, B., Eslick, G. D. & Sunner, P. Internal versus external fixation of the anterior component in unstable fractures of the pelvic ring: Pooled results from a systematic review. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 42, 635–643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-015-0554-4 (2016).

Tosounidis, T. H., Sheikh, H. Q., Kanakaris, N. K. & Giannoudis, P. V. The use of external fixators in the definitive stabilisation of the pelvis in polytrauma patients: Safety, efficacy and clinical outcomes. Injury 48, 1139–1146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2017.03.033 (2017).

Rommens, P. M. et al. Minimal-invasive stabilization of anterior pelvic ring fractures with retrograde transpubic screws. Injury 51, 340–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2019.12.018 (2020).

Herteleer, M., Boudissa, M., Hofmann, A., Wagner, D. & Rommens, P. M. Plate fixation of the anterior pelvic ring in patients with fragility fractures of the pelvis. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-021-01625-z (2021).

Bastian, J. D. et al. Anterior fixation of unstable pelvic ring fractures using the modified Stoppa approach: Mid-term results are independent on patients’ age. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 42, 645–650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-015-0577-x (2016).

Wilson, D. G. G., Kelly, J. & Rickman, M. Operative management of fragility fractures of the pelvis—a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 22, 717. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04579-w (2021).

Schuetze, K. et al. Short-term outcome of fragility fractures of the pelvis in the elderly treated with screw osteosynthesis and external fixator. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-021-01780-3 (2021).

Rommens, P. M. et al. Operative treatment of fragility fractures of the pelvis is connected with lower mortality. A single institution experience. PLoS One 16, e0253408. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253408 (2021).

Gericke, L. et al. Percutaneous operative treatment of fragility fractures of the pelvis may not increase the general rate of complications compared to non-operative treatment. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-021-01660-w (2021).

Oberkircher, L. et al. Which factors influence treatment decision in fragility fractures of the pelvis?—results of a prospective study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 22, 690. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04573-2 (2021).

Fritz, A., Gericke, L., Höch, A., Josten, C. & Osterhoff, G. Time-to-treatment is a risk factor for the development of pressure ulcers in elderly patients with fractures of the pelvis and acetabulum. Injury 51, 352–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2019.12.007 (2020).

Saito, Y. et al. Does surgical treatment for unstable fragility fracture of the pelvis promote early mobilization and improve survival rate and postoperative clinical function?. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-021-01729-6 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing. The authors acknowledge the support of the German Pelvic Injury Register of the German Society of Traumatology (Deutsche Gesellschaft fuer Unfallchirurgie, DGU) and the German section of AO. The authors thank Dr. Med. Mara Sandrock for the illustration of Figs. 1 and 2. The authors acknowledge support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) and Leipzig University within the program of Open Access Publishing.

Philipp Pieroh, Florian Gras, Sven Märdian, Steven C. Herath, Hans-Georg Palm, Christoph Josten, Fabian M. Stuby, Daniel Wagner, Andreas Höch are members of the German Pelvic Injury Register of the German Society of Traumatology (Deutsche Gesellschaft fuer Unfallchirurgie [DGU]) and the German section of AO.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: P.P., D.W. Data acquisition and taking part as investigator/rater: P.P., D.W., F.G., S.M., A.P., S.W., C.I., N.B., K.D.-L., T.S., S.C.H., H.-G.P., F.M.S., A.H. Analysed the data: P.P., D.W., T.H. Project supervision: C.J., F.M.S., A.H. Wrote the paper: P.P., D.W., A.H. Approved the final version of the manuscript: P.P., D.W., T.H., S.M., A.P., S.W., C.I., N.B., K.D.-L., T.S., S.C.H., H.-G.P., C.J., F.M.S., A.H.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The German Research Foundation (DFG) and Leipzig University supported this work within the program of Open Access Publishing. DFG and Leipzig University had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results. The authors declare no further conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pieroh, P., Hohmann, T., Gras, F. et al. A computed tomography based survey study investigating the agreement of the therapeutic strategy for fragility fractures of the pelvis. Sci Rep 12, 2326 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-04949-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-04949-x

This article is cited by

-

Die Sakrum-H-Fraktur zwischen traumatischer, Insuffizienz- und Ermüdungsfraktur

Die Unfallchirurgie (2023)

-

Fragility Fractures of the Pelvis: Current Practices and Future Directions

Current Osteoporosis Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.