Abstract

This meta-analysis systematically reviewed the evidence on standardized acceptance-/mindfulness-based interventions in DSM-5 anxiety disorders. Randomized controlled trials examining Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) were searched via PubMed, Central, PsycInfo, and Scopus until June 2021. Standardized mean differences (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for primary outcomes (anxiety) and secondary ones (depression and quality of life). Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane tool. We found 23 studies, mostly of unclear risk of bias, including 1815 adults with different DSM-5 anxiety disorders. ACT, MBCT and MBSR led to short-term effects on clinician- and patient-rated anxiety in addition to treatment as usual (TAU) versus TAU alone. In comparison to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), ACT and MBCT showed comparable effects on both anxiety outcomes, while MBSR showed significantly lower effects. Analyses up to 6 and 12 months did not reveal significant differences compared to TAU or CBT. Effects on depression and quality of life showed similar trends. Statistical heterogeneity was moderate to considerable. Adverse events were reported insufficiently. The evidence suggests short-term anxiolytic effects of acceptance- and mindfulness-based interventions. Specific treatment effects exceeding those of placebo mechanisms remain unclear. Protocol registry: Registered at Prospero on November 3rd, 2017 (CRD42017076810).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anxiety disorders differ from normative fear or anxiety by featuring exaggerated symptoms lasting persistently over a prolonged period of time that interfere with daily activities. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) classifies anxiety disorders as Separation Anxiety Disorder, Selective Mutism, Social Anxiety Disorder, Panic Disorder, Agoraphobia, Specific Phobias, and Generalized Anxiety Disorder1. Globally, the one-year prevalence of anxiety disorders ranges from 2.4% to 29.8% with a point prevalence of 7.3%2, while subthreshold anxiety cases are even more common3. For most anxiety diagnoses, women are twice often affected than men4,5. Patients with anxiety disorders report high rates of co-morbidity6 and often suffer from disturbed sleep, headaches, depressed mood, gastrointestinal or cardiovascular problems7,8 leading to increasing costs of health care utilization and work loss9.

As the first-line treatment of anxiety disorders, clinical practice guidelines recommend psychological therapies, particularly Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) in preference to or in combination with pharmacotherapy10,11,12. Another treatment option with promising evidence for alleviating anxiety symptoms in non-psychiatric samples13,14,15,16,17 are mindfulness-based interventions such as Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR), Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), and Acceptance Commitment Therapy (ACT). MBSR is a standardized group program of 8 weekly sessions lasting an average of 2.5 h combined with an additional silent retreat day. Core components of MBSR include sitting and walking meditation, yoga asanas, and mindful relaxation techniques. Daily home practice is demanded to integrate mindfulness into everyday life18. MBCT combines mindfulness elements with cognitive-behavioral methods like psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, and the development of pleasant activities – also within an 8-week group setting including a retreat day and daily home practice19. ACT combines acceptance-based and mindfulness strategies with cognitive-behavioral techniques and focuses on accepting experiences while being present, choosing goals according to values, and then taking committed action. ACT is usually an individual-based approach, but also offers group concepts mostly for non-clinical populations20. For patients with manifest anxiety disorders, previous systematic reviews of MBSR, MBCT, and ACT with and without meta-analysis suggest significant greater effects in comparison to usual care and comparable effects to CBT but used outdated methodology or focused on single anxiety disorders, mixed anxiety/obsessive–compulsive and depressive syndromes, or elderly patients/children21,22,23,24,25,26. To date, there is no comprehensive meta-analysis that assesses and compares the effectiveness and safety of standardized MBSR, MBCT, and ACT in the management of adult patients with DSM-5 anxiety disorders.

Methods

The systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines27 and the Cochrane recommendations28. Before starting the review, the protocol was registered at Prospero (CRD42017076810).

Study selection

Types of studies: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or randomized crossover trials were eligible.

Types of patients: Eligible samples included adults diagnosed with an anxiety disorder as defined by DSM-51 including:

-

Separation Anxiety Disorder (DSM-5: 309.21/ICD-10: F93.0),

-

Selective Mutism (DSM-5: 321.23/ICD-10: F94.0),

-

Specific Phobias (DSM-5: 300.29/ICD-10: F40.218, F40.228, F40.23x, F40.248, F40.298),

-

Social Anxiety Disorder (DSM-5: 300.23/ICD-10: F40.10),

-

Panic Disorder (DSM-5: 300.01/ICD-10: F41.0),

-

Agoraphobia (DSM-5: 300.22/ICD-10: F40.00),

-

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (DSM-5: 300.02/ICD-10: F41.1),

-

Other Specified (DSM-5: 300.09/ICD-10: F41.8), and

-

Unspecified Anxiety Disorder (DSM-5: 300.00/ICD-10: F41.9).

Patients who were diagnosed by prior versions of the DSM/ICD were also eligible, if their diagnosis is listed as a DSM-5 anxiety disorder as well. Studies involving patients with anxiety comorbid with other physical/mental disorders were eligible, if the comorbidity was not examined as the primary study outcome. Studies including heterogeneous psychiatric populations such as patients with anxiety disorders as well as those with depression or obsessive–compulsive disorder were excluded, while studies assessing mixed anxiety diagnoses (as defined above) were considered as well.

Types of interventions: Standardized acceptance- or mindfulness-based interventions like MBSR, MBCT, ACT, and variations of these programs (regardless of program length, frequency, or setting) were eligible. Studies allowing individual co-interventions were eligible as long as all participants in all groups received the same co-interventions. Acceptable control interventions were no treatment/wait-list or treatment as usual (TAU) as well as any other active treatments.

Types of outcomes: Improvement in the severity of anxiety symptoms measured by validated clinician- and/or patient-rated scales closest to 2 months after randomization (short-term) were defined as primary outcomes. Secondary outcomes included anxiety symptoms closest to 6 months and 12 months after randomization and safety. The severity of depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life were included as secondary outcomes as well, as anxiety disorders have high rates of comorbidity with depressive symptoms and reduced quality of life. If an outcomes was assessed by more than one instrument, primary endpoints were preferred over secondary ones, disease-specific instruments over generic ones and multi-item over single-item ones. Safety was assessed as the number of adverse events (AE) or study withdrawals due to AEs. AEs were defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a patient, without necessarily having a causal relationship with the study treatment. Cases of any untoward medical occurrence that had resulted in death, was life-threatening, required inpatient hospitalization, or caused persistent or significant disability were rated as serious AEs29.

Data sources

PubMed, Central, PsycInfo, and Scopus were searched from their inception to June 22nd, 2020. An update was executed in PubMed until June 14th, 2021. Table 1 shows the search strategy in PubMed, which was adapted for each database as necessary. No language restrictions were applied. Moreover, we manually searched reference lists of previous reviews. For ongoing and unpublished studies, we searched international trial registries of the WHO and the NIH applying identical search terms. Two reviewers (HH and PB) independently screened titles and abstracts and assessed full-texts for eligibility using EndNote. Any disagreement were rechecked with a third reviewer (HC) until consensus was achieved.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (PB and MS) independently extracted predefined data on the study setting and characteristics of the included studies. All Discrepancies were rechecked with a third reviewer (HH) until consensus was achieved.

For each study, the risk of selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other source of bias were independently assessed by two reviewers (PB and MS) using the Cochrane risk of bias tool28. Each domain was assessed as either, ‘low risk of bias’ if all requirements were adequately fulfilled, ‘high risk of bias’ if the requirements were not adequately fulfilled, and as ‘unclear risk of bias’ if insufficient data for a judgment was provided. Divergent assessments were rechecked with a third reviewer (HC) until consensus was achieved.

Data synthesis

Overall analyses

If at least two studies had assessed the same outcome to the same defined time point with the same type of control intervention, pairwise meta-analyses using random-effects models (inverse variance method) with Hedges’ correction for small samples28 were conducted using Review Manager Software (RevMan, Version 5.3, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen). For continuous outcomes, standardized mean differences (SMDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated indicating the difference in means between groups divided by the pooled standard deviation (SD). In cases where no SDs were published, they were calculated from standard errors, CIs or t-values28, or were requested from trial authors by email. A negative SMD indicated greater effects of the experimental intervention over the respective control condition, except for quality of life. In accordance with Cohen’s categories, SMDs of 0.2–0.5 were interpreted as small effects, SMDs of 0.5–0.8 as medium effects, and SMDs > 0.8 as large effects30. For binary outcomes such as AEs, risk ratio analyses were planned. However, as most studies did not report AEs systematically, AEs were analyzed descriptively.

Assessment of statistical heterogeneity

Statistical heterogeneity between the study effects was analyzed by the Chi2 statistics with a p-value of ≤ 0.10 indicating significant heterogeneity. The magnitude of heterogeneity was categorized by the I2 with I2 > 25%, I2 > 50%, and I2 > 75% representing moderate, substantial, and considerable heterogeneity, respectively28,31.

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses were planned for patients with different anxiety diagnoses and different mindfulness interventions but could only be realized for the latter, as the number of studies for comparisons was too small.

Sensitivity analyses

We conducted sensitivity analyses, where studies with high or unclear risk of bias were compared with those of low risk of bias. If substantial or considerable statistical heterogeneity was present in a meta-analysis, we used sensitivity analyses to explore heterogeneity in effect estimates.

Risk of bias across studies

The assessment of publication bias was planned by visual analysis of funnel plots and Egger's test, if more than 10 studies were included in a meta-analysis32.

Results

Literature search

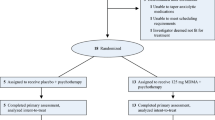

The electronic search revealed 7651 articles, a PubMed update additional 362 ones (Fig. 1). After the exclusion of supplicates and non-eligible abstracts, 49 articles were red in full. We excluded further 9 ones as they reported data of an already included sample33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41, 8 as they included mixed anxiety disorders containing patients with other than the defined DSM-5 anxiety diagnoses42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49, 2 articles because of younger aged samples50,51, 2 as they did not include a predefined outcome52,53, and 4 articles as they did not contain a predefined control group54,55,56,57. One additional study did not investigate a standardized ACT, MBCT, or MBSR program58. Thus, 23 RCTs published between 2007 and 2021 including 1815 patients were included in the meta-analysis59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81. Searching of trial registries revealed no additional unpublished or ongoing studies.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the included RCTs are presented in detail in Table 2. The RCTs were conducted in the US, Sweden, Canada, Germany, Norway, Brazil, Japan, Iran, Romania, and China and investigated patients diagnosed with Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Social Anxiety Disorder, and mixed anxiety diagnoses. Samples randomized ranged from 24 to 182 with a median N of 81 containing a median of 67.1% of women. The participants’ median age was 35.3 years.

Twelve RCTs investigated ACT interventions, 3 ones MBCT, and 8 ones MBSR. Individual- and group-based approaches varied as well as online and offline/in-person settings. Control interventions included TAU/wait-list, individualized or group-based CBT, psychoeducation, and relaxation. The median duration of the study treatments was 10 (4 to 16) weeks. Concurrent psychotropic drug use was reported by a median of 26.1% of the participants.

All studies provided data directly after the end of the intervention. Seven RCTs assessed a follow-up closest to 6 months after randomization, 4 RCTs additionally closest to 12 months after randomization. Outcomes included clinician-rated severity of anxiety, patient-rated severity of anxiety, patient-rated severity of depression, and patient-rated health-related quality of life.

Funding was reported by all but 3 RCTs and contained no specific funding (3 RCTs), university grants (4 RCTs), governmental grants (8 RCTs), university and governmental funding (1 RCT), private foundations (3 RCTs), and industrial funding (1 RCT).

Risk of bias of individual studies

Risk of selection bias was assessed as low in 21.7% of the included studies. Additional 30.4% reported adequate random sequence generation but did not provide information or reported in-adequate information about allocation concealment. No study had low risk of performance bias. The risk of detection bias was low in 60.9% of the studies. Here, a low risk of bias judgement was also given in cases, when the outcome was clinician-reported and the clinician was blinded to group allocation but also when the staff who handed out the patient questionnaires was blinded, even if patients cannot be blinded. The same amount of the studies (60.9%) were assessed as low risk of attrition bias as they recorded less than 10% drop-outs per group or/and performed intention-to treat analysis. The risk of reporting bias and possible risks of other sources of bias were low in 21.7% and 78.3% of the studies, respectively (Fig. 2).

Pooling of effects

Clinician-rated anxiety

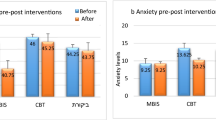

ACT showed a significantly larger short-term effect than TAU on clinician-rated anxiety (4 RCTs, SMD = −0.98, 95%CI = [−1.50, −0.46], I2 = 62%, N = 204). The substantial heterogeneity could be reduced by excluding one RCT65 with mostly high/unclear risk of bias and the only effect which crossed zero (3 RCTs, SMD = −1.16, 95%CI = [−1.52, −0.80], I2 = 5%, N = 152) (Fig. 3). The analyses were robust against risk of detection bias, attrition bias, and other bias. In comparison to CBT, ACT homogeneously showed non-significant short-term (3 RCTs, SMD = 0.13, 95%CI = [−0.17, 0.43], I2 = 0%, N = 176) and medium-term effects up to 6 months (2 RCTs, SMD = 0.26, 95%CI = [−0.10, 0.62], I2 = 0%, N = 121) (Fig. 3). However, for both analyses, only the risk of detection bias and other bias was low. Up to 12 months, again no significant differences were found between ACT and CBT61. In comparison to less complex psychological interventions such as psychoeducation or relaxation, ACT did not show a significant larger effect (2 RCTs, SMD = −0.18, 95%CI = [−1.00, 0.64], I2 = 77%, N = 107) (Fig. 3). Because of the considerable heterogeneity, the pooled effect should be interpreted with restraint, also because one of the RCTs63 reported significant medium-term effects of ACT against psychoeducation. Detailed analyses can be found in the Supplementary Fig. 1.

Forest plot summary of the effects on primary and secondary outcomes. Legend. ACT: Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; AR: Applied relaxation; CBT: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; CI: Confidence interval; I2: Measure of statistical heterogeneity; IV: Inverse variance; MBCT: Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy; MBSR: Mindfulness-based stress reduction; PE: Psychoeducation; TAU: Treatment as usual.

One further RCT investigated MBSR against TAU and showed significantly higher improvements on clinician-rated anxiety up to 2 months post randomization75, while as compared to CBT, MBSR showed significantly lower short-term improvements (2 RCTs, SMD = 0.50, 95%CI = [0.17, 0.83], I2 = 0%, N = 147) (Fig. 1).

Further 2 RCTs of mostly unclear risk of bias, one on MBCT against CBT77 and another on MBSR against psychoeducation69 did not show any significant short-term superiority of the respective interventions.

Patient-rated anxiety

The meta-analyses of ACT in comparison to TAU revealed a significantly larger effect in favor of ACT (7 RCTs, SMD = −0.99, 95%CI = [−1.47, −0.50], I2 = 84%, N = 488) but revealed considerable heterogeneity, which could be decreased by excluding one RCT64 with the greatest effect in favor of ACT and the weakest study quality (6 RCTs, SMD = −0.67, 95%CI = [−0.87, −0.47], I2 = 0%, N = 448) (Fig. 3). The effect was robust against the risk of selection bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other bias. No significant differences occurred for ACT versus TAU at 6 months (2 RCS, SMD = −2.55, 95%CI = [−5.57, 0.46], I2 = 94%, N = 62), while both individual trials64,71 reported significant differences. However, the two RCTs were both of unclear/high risk of bias and included very small samples, which may explain the considerable heterogeneity. The meta-analysis of ACT versus CBT contained RCTs with mostly unclear/high risk of bias and revealed neither significant short-term (4 RCTs, SMD = 0.21, 95%CI = [−0.14, 0.57], I2 = 52%, N = 284) nor medium-term (2 RCTs, SMD = 0.20, 95%CI = [−0.17, 0.56], I2 = 0%, N = 116) (Fig. 3) or longer-term differences61 between the two therapies. In comparison to less complex psychological interventions, ACT led to no significantly different short-term effect (2 RCTs, SMD = −0.16, 95%CI = [−0.54, 0.22], I2 = 0%, N = 107) (Fig. 3).

The meta-analyses of MBCT revealed a significant larger but heterogeneous short-term effect than TAU (2 RCTs, SMD = −0.89, 95%CI = [−160, −0.18], I2 = 71%, N = 161) (Fig. 3). At 6 months, a single RCT reported persisting longer-term effects as well81. In comparison to CBT, MBCT did not lead to significantly larger short-term effects77. MBCT and psychoeducation at 2, 6, and 12 months did not significantly differ from each other81.

The meta-analysis of MBSR versus TAU showed a significantly larger short-term effect in favor of MBSR (4 RCTs, SMD = −1.42, 95%CI = [−2.34, −0.50], I2 = 88%, N = 218) (Fig. 3). While the heterogeneity could not be reduced by excluding individual RCTs, the effect remained significant when excluding the RCTs with unclear/high risk of detection bias, attrition bias, and other bias. In comparison to CBT, the meta-analysis showed significantly lower improvements for MBSR (3 RCTs, SMD = 0.50, 95%CI = [0.23, 0.76], I2 = 0%, N = 222) (Fig. 1). In comparison to psychoeducation, MBSR showed a significantly larger short-term effect (2 RCTs, SMD = −0.66, 95%CI = [−1.30, −0.03], I2 = 78%, N = 180) (Fig. 3). The meta-analysis contained considerable heterogeneity but could be considered as robust against all risk of bias domains except the risk of performance bias. Detailed analyses on patient-rated anxiety is provided in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Depressive symptoms

For depressive symptoms, the meta-analysis revealed significantly higher short-term effects of ACT than of TAU (5 RCTs, SMD = −0.54, 95%CI = [−0.82, −0.27], I2 = 34%, N = 398), which was found to be robust against risk of selection bias, detection bias, and other bias. In comparison to CBT (2 RCTs, SMD = 0.33, 95%CI = [−0.40, 1.06], I2 = 76%, N = 151) and less complex psychological interventions (2 RCTs, SMD = 0.02, 95%CI = [−0.36, 0.40], I2 = 0%, N = 107), ACT did not reveal larger short-term effects (Fig. 3). Longer-term effects at 12 months did also not significantly differ from psychoeducation67.

For MBCT, the meta-analysis did not show significantly higher effects on depressive symptoms against TAU, neither at short-term (2 RCTs, SMD = −0.73, 95%CI = [−1.61, 0.15], I2 = 81%, N = 161) nor at 6 months81. Short- and longer-term effects did not differ between MBCT and CBT77 or psychoeducation81.

For MBSR, the meta-analysis revealed significantly larger short-term anti-depressive effects against TAU (4 RCTs, SMD = −1.13, 95%CI = [−1.96, −0.31], I2 = 86%, N = 218). The considerable heterogeneity could be reduced by excluding one low-quality RCT with the largest effect that compared MBSR to TAU without using a waiting list59. This resulted in still significantly higher short-term effects of MBSR compared to TAU (3 RCTs, SMD = −0.58, 95%CI = [−0.87, −0.28], I2 = 0%, N = 187) (Fig. 3). The effect was robust against risk of detection bias, attrition bias, and other bias. In comparison to CBT, no superiority of MBSR on depressive symptoms could be detected (3 RCTs, SMD = 0.07, 95%CI = [−0.24, 0.37], I2 = 23%, N = 222) (Fig. 3). One additional RCT showed that MBSR was superior to psychoeducation in reducing short-term depressive symptoms60. Detailed analyses on depression can be found in the Supplementary Fig. 3.

Quality of life

ACT showed no significantly different short-term effect on quality of life compared to TAU (4 RCTs, SMD = 0.32, 95%CI = [−0.01, 0.65], I2 = 42%, N = 271), CBT (2 RCTs, SMD = −0.37, 95%CI = [−0.85, 0.11], I2 = 33%, N = 107) or less complex psychotherapeutic interventions (2 RCTs, SMD = 0.14, 95%CI = [−0.53, 0.82], I2 = 67%, N = 107) (Fig. 3). Longer-term effects of ACT did not significantly differ from those of CBT at 6 and 12 months61, were reported as significantly higher as those of psychoeducation at 6 months63, but not significantly different from those of relaxation at 12 months67.

MBCT was found to be superior to TAU in the short-term (2 RCTs, SMD = 0.43, 95%CI = [0.11, 0.74], I2 = 0%, N = 161) (Fig. 3), but not to CBT77 or to psychoeducation81. More detailed analyses can be found in the Supplementary Fig. 4.

Further RCTs reported significantly higher short-term effects on quality of life in favor of MBSR compared to TAU80 but not compared to CBT73 or psychoeducation60.

Safety

Safety data were reported insufficiently (Tab. 2). Fourteen RCTs did not report any information on AEs or reasons for study withdrawal. Serious AEs were reported by one RCT in the ACT group (bypass surgery), which was highly likely not related to the study intervention67. Minor AEs were equally distributed between experimental and control groups65,69,73,74,75,76,77,80.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

The literature search revealed 23 RCTs investigating the effectiveness of ACT, MBCT, and MBSR in patients with DSM-5 anxiety disorders such as Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Social Anxiety Disorder, and mixed samples including different anxiety diagnoses. The meta-analyses revealed at least short-term effects on clinician- and patient-rated anxiety for ACT, MBCT and MBSR in addition to TAU versus TAU alone. In comparison to CBT, ACT and MBCT showed comparable effects on both anxiety outcomes, while MBSR showed significantly lower effects. Pooled effects up to 6 months post randomization can only be calculated for ACT but did not show any significant differences compared to TAU or CBT. Short-term effects of ACT, MBCT and MBSR on secondary outcomes were superior against TAU but not against CBT or less complex psychotherapeutic interventions such as psychoeducation or applied relaxation. Most effects were robust against most risk of bias domains. However, the risk of selection bias and performance bias remains unclear or high for almost all meta-analyses. Statistical heterogeneity could be reduced in several meta-analyses by excluding low-quality studies with extreme values. A correlation of those extreme values with funding concerns from industrial companies or private foundations could not be determined. Moreover, comparisons to CBT should be interpreted with restraint as the number of included trials was very low and none of the studies tested non-inferiority. Adverse events were reported insufficiently. If safety issues were reported, ACT, MBCT, and MBSR did not lead to more adverse events than usual care and comparable adverse events to CBT.

In contrast to prior systematic reviews, which found promising effects of mindfulness on anxiety symptoms in the general population13,14,23 and somatically ill samples15,17, the evidence for patients with manifest DSM-5 anxiety disorders should be interpreted with restraint. Reasons include the low number of studies investigating longer-term effects against eligible control conditions such as CBT, the overall unclear study quality, and the often missed systematic assessment and reporting of adverse events.

Limitations

This meta-analysis has further limitations. We often were not able to pool data of RCTs because of non-comparable controls, or could perform sensitivity analyses of comparisons including only 2 RCTs. In addition, we were not able to calculate subgroup analyses of different anxiety disorders. Thus, the present meta-analysis does not allow to draw conclusions for a specific diagnosis. Since risk of publication bias could not be assessed, the effects might also be overestimated due to unpublished studies, even if the search of trial registries did not result in registered but unpublished studies82.

Implications for further research

Further higher-quality trials on mindfulness-based interventions are needed to verify the effects in patients with manifest anxiety disorders. Authors should ensure rigorous methodology and reporting according to CONSORT83 and choose adequate control conditions. Recent meta-analyses on pharmacological and psychological intervention for anxiety disorders conclude that wait-list control groups may produce nocebo effects in trials of psychotherapy84. TAU, in addition, was also found to be a very heterogeneous control condition and anything but usual or standard care85,86. Psychological placebo effects were estimated on average 0.83 in patients with anxiety disorders87. Thus, adequate control groups for trials on manifest disorders rather than subclinical symptoms should be designed considering nocebo as well as placebo effects. Non-inferiority trials against standard psychotherapies such as CBT are missing completely. To enhance study quality and reduce the risk of performance bias, even if patients and therapists cannot be blinded, controlling for patients’ treatment expectations and their perceptions of quality of the alliance towards the treating therapist would be feasible. Blinding of outcome assessors, especially for clinician-rated outcomes as well as more adequate statistics (including intention-to-treat analyses) should be standard. Future studies are requested to strictly report AEs and reasons of drop-out.

Conclusions

The evidence suggests clinically relevant short-term anxiolytic effects of acceptance-based and with less extent of mindfulness-based interventions when added to usual care that, however, might be a result of nocebo- and/or placebo effects. The relevance of longer-term effects as well as the comparability to standard CBT remain preliminary until further high-quality studies will be published.

Data availability

The data and material analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Code availability

The RevMan code used for the current study is available from the corresponding author on request.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013).

Baxter, A. J., Scott, K. M., Vos, T. & Whiteford, H. A. Global prevalence of anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-regression. Psychol. Med. 43, 897–910. https://doi.org/10.1017/s003329171200147x (2013).

Haller, H., Cramer, H., Lauche, R., Gass, F. & Dobos, G. J. The prevalence and burden of subthreshold generalized anxiety disorder: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 14, 128. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-128 (2014).

Grenier, S. et al. Association of age and gender with anxiety disorders in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 34, 397–407. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5035 (2019).

Gustavson, K. et al. Prevalence and stability of mental disorders among young adults: Findings from a longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry 18, 65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1647-5 (2018).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62, 593–602. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593 (2005).

Nabi, H. et al. Psychological and somatic symptoms of anxiety and risk of coronary heart disease: The health and social support prospective cohort study. Biol. Psychiat. 67, 378–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.040 (2010).

Pelletier, L., O’Donnell, S., McRae, L. & Grenier, J. The burden of generalized anxiety disorder in Canada. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada : Research, Policy and Practice 37, 54–62. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.37.2.04 (2017).

Wittchen, H. U. et al. The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 21, 655–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018 (2011).

Bandelow, B. et al. Deutsche S3-Leitlinie Behandlung von Angststörungen. (2014). https://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/051-028l_S3_Angstst%C3%B6rungen_2014-05_2.pdf.

Katzman, M. A. et al. Canadian clinical practice guidelines for the management of anxiety, posttraumatic stress and obsessive-compulsive disorders. BMC Psychiatry 14(Suppl 1), S1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244x-14-s1-s1 (2014).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults: management. (2019). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg113/resources/generalised-anxiety-disorder-and-panic-disorder-in-adults-management-pdf-35109387756997.

Gotink, R. A. et al. Standardised mindfulness-based interventions in healthcare: An overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs. PLoS ONE 10, e0124344. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0124344 (2015).

Guillaumie, L., Boiral, O. & Champagne, J. A mixed-methods systematic review of the effects of mindfulness on nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 73, 1017–1034. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13176 (2017).

Haller, H. et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for women with breast cancer: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncologica (Stockholm, Sweden) 56, 1665–1676. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186x.2017.1342862 (2017).

Kishita, N., Takei, Y. & Stewart, I. A meta-analysis of third wave mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapies for older people. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 32, 1352–1361. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4621 (2017).

Schell, L. K., Monsef, I., Wockel, A. & Skoetz, N. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for women diagnosed with breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 3, Cd011518. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011518.pub2 (2019).

Kabat-Zinn, J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 4, 33–47 (1982).

Teasdale, J. D. et al. Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 68, 615–623. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.4.615 (2000).

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A. & Lillis, J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 44, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006 (2006).

Norton, A. R., Abbott, M. J., Norberg, M. M. & Hunt, C. A systematic review of mindfulness and acceptance-based treatments for social anxiety disorder. J. Clin. Psychol. 71, 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22144 (2015).

Costa, M., Oliveira, G., Tatton-Ramos, T., Manfro, G. & Salum, G. Anxiety and stress-related disorders and mindfulness-based interventions: A systematic review and multilevel meta-analysis and meta-regression of multiple outcomes. Mindfulness 10, 996–1005. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1058-1 (2018).

Li, S. Y. H. & Bressington, D. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on depression, anxiety, and stress in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 28, 635–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12568 (2019).

Ruiz-Íñiguez, R., Santed Germán, M. Á., Burgos-Julián, F. A., Díaz-Silveira, C. & Carralero Montero, A. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions on anxiety for children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Early Interv. Psychiatry 14, 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12849 (2020).

Coto-Lesmes, R., Fernández-Rodríguez, C. & González-Fernández, S. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in group format for anxiety and depression. A systematic review. J. Affect. Disorders 263, 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.154 (2020).

Ghahari, S., Mohammadi-Hasel, K., Malakouti, S. K. & Roshanpajouh, M. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for generalised anxiety disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. East Asian Arch. Psychiatry 30, 52–56. https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap1885 (2020).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G. & Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 8, 336–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007 (2010).

Higgins, J. P. & Thomas, J. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 6.2. (2021). https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current.

European Medicines Agency. ICH Harmonized Tripartite Guideline E6: Note for Guidance on Good Clinical Practice (PMP/ICH/135/95). (European Medicines Agency, 2002).

Ellis, P. D. The essential guide to effect sizes. Statistical power, meta-analysis, and the interpretation of research results (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J. & Altman, D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327, 557–560. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 (2003).

Egger, M., Davey Smith, G., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315, 629–634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 (1997).

Butler, R. M. et al. Emotional clarity and attention to emotions in cognitive behavioral group therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction for social anxiety disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 55, 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.03.003 (2018).

Jazaieri, H., Goldin, P. R. & Gross, J. J. The role of working alliance in cbt and mbsr for social anxiety disorder. Mindfulness, No Pagination Specified. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0877-9 (2018).

Millstein, D. J., Orsillo, S. M., Hayes-Skelton, S. A. & Roemer, L. Interpersonal problems, mindfulness, and therapy outcome in an acceptance-based behavior therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 44, 491–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2015.1060255 (2015).

Thurston, M. D., Goldin, P., Heimberg, R. & Gross, J. J. Self-views in social anxiety disorder: The impact of CBT versus MBSR. J. Anxiety Disord. 47, 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.01.001 (2017).

Wong, S. Y. et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for generalised anxiety disorder and health service utilisation among Chinese patients in primary care: a randomised, controlled trial. Hong Kong medical journal = Xianggang yi xue za zhi 22(Suppl 6), 35–36 (2016).

Brown, L. A. et al. Self-referential processing during observation of a speech performance task in social anxiety disorder from pre- to post-treatment: Evidence of disrupted neural activation. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 284, 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2018.12.017 (2019).

Horenstein, A. et al. Sleep quality and treatment of social anxiety disorder. Anxiety Stress Coping 32, 387–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2019.1617854 (2019).

Morrison, A. S. et al. Changes in empathy mediate the effects of cognitive-behavioral group therapy but not mindfulness-based stress reduction for social anxiety disorder. Behav. Ther. 50, 1098–1111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2019.05.005 (2019).

Sewart, A. R. et al. Examining positive and negative affect as outcomes and moderators of cognitive-behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy for social anxiety disorder. Behav. Ther. 50, 1112–1124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2019.07.001 (2019).

Arch, J. J. et al. Randomized clinical trial of adapted mindfulness-based stress reduction versus group cognitive behavioral therapy for heterogeneous anxiety disorders. Behav. Res. Ther. 51, 185–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2013.01.003 (2013).

Arch, J. J. et al. Randomized clinical trial of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) versus acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for mixed anxiety disorders. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 80, 750–765. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028310 (2012).

Lang, A. J. et al. Randomized controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy for distress and impairment in OEF/OIF/OND veterans. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 9, 74–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000127 (2017).

Ritzert, T. R. et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of ACT for anxiety disorders in a self-help context: outcomes from a randomized wait-list controlled trial. Behav. Ther. 47, 444–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2016.03.001 (2016).

Finnes, A., Ghaderi, A., Dahl, J., Nager, A. & Enebrink, P. Randomized controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy and a workplace intervention for sickness absence due to mental disorders. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 24, 198–212. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000097 (2019).

Haddad, R. et al. Does patient expectancy account for the cognitive and clinical benefits of mindfulness training in older adults?. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 35, 626–632. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5279 (2020).

Kladnitski, N. et al. Transdiagnostic internet-delivered CBT and mindfulness-based treatment for depression and anxiety: A randomised controlled trial. Internet Interv 20, 100310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2020.100310 (2020).

Ruiz, F. J. et al. Efficacy of a two-session repetitive negative thinking-focused acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) protocol for depression and generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized waitlist control trial. Psychotherapy (Chic.) https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000273 (2020).

Alimehdi, M., Ehteshamzadeh, P., Naderi, F., Eftekharsaadi, Z. & Pasha, R. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction on intolerance of uncertainty and anxiety sensitivity among individuals with generalized anxiety disorder. Asian Soc. Sci. 12, 179–187. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v12n4p179 (2016).

Azadeh, S. M., Kazemi-Zahrani, H. & Besharat, M. A. Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on interpersonal problems and psychological flexibility in female high school students with social anxiety disorder. Global J. Health Sci. 8, 131–138. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v8n3p131 (2015).

Hoge, E. A. et al. The effect of mindfulness meditation training on biological acute stress responses in generalized anxiety disorder. Psychiatry Res. 262, 328–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.006 (2018).

MacCoon, D. G. et al. The validation of an active control intervention for Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). Behav. Res. Ther. 50, 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.10.011 (2012).

Gershkovich, M., Herbert, J. D., Forman, E. M., Schumacher, L. M. & Fischer, L. E. Internet-delivered acceptance-based cognitive-behavioral intervention for social anxiety disorder with and without therapist support: A randomized trial. Behav. Modif. 41, 583–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445517694457 (2017).

Goldin, P. R., Ziv, M., Jazaieri, H. & Gross, J. J. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction versus aerobic exercise: Effects on the self-referential brain network in social anxiety disorder. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6, 295. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00295 (2012).

Navarro-Haro, M. V. et al. Evaluation of a mindfulness-based intervention with and without virtual reality dialectical behavior therapy® mindfulness skills training for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in primary care: A pilot study. Front. Psychol. 10, 55. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00055 (2019).

Villatte, J. L. et al. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy modules: Differential impact on treatment processes and outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 77, 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.001 (2016).

Costa, M. A. et al. A three-arm randomized clinical trial comparing the efficacy of a mindfulness-based intervention with an active comparison group and fluoxetine treatment for adults with generalized anxiety disorder. Psychother. Psychosom. https://doi.org/10.1159/000511880 (2020).

Asmaee Majid, S., Seghatoleslam, T., Homan, H., Akhvast, A. & Habil, H. Effect of mindfulness based stress management on reduction of generalized anxiety disorder. Iran. J. Public Health 41, 24–28 (2012).

Boettcher, J. et al. Internet-based mindfulness treatment for anxiety disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Behav. Ther. 45, 241–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2013.11.003 (2014).

Craske, M. G. et al. Randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy for social phobia: outcomes and moderators. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 82, 1034–1048. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037212 (2014).

Dahlin, M. et al. Internet-delivered acceptance-based behaviour therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 77, 86–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.007 (2016).

de Almeida Sampaio, T. P. et al. Efficacy of an acceptance-based group behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Depress. Anxiety https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23021 (2020).

Fathi, R., Khodarahimi, S. & Rasti, A. The efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy on metacognitions and anxiety in women outpatients with generalized anxiety disorder in Iran. Can. J. Counsell. Psychother. 51, 207–216 (2017).

Gloster, A. T. et al. Treating treatment-resistant patients with panic disorder and agoraphobia using psychotherapy: A randomized controlled switching trial. Psychother. Psychosom. 84, 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1159/000370162 (2015).

Goldin, P. R. et al. Group CBT versus MBSR for social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 84, 427–437. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000092 (2016).

Hayes-Skelton, S. A., Roemer, L. & Orsillo, S. M. A randomized clinical trial comparing an acceptance-based behavior therapy to applied relaxation for generalized anxiety disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 81, 761–773. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032871 (2013).

Herbert, J. D. et al. Randomized controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy versus traditional cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder: Symptomatic and behavioral outcomes. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 9, 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2018.07.008 (2018).

Hoge, E. A. et al. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for generalized anxiety disorder: effects on anxiety and stress reactivity. J. Clin. Psychiatry 74, 786–792. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.12m08083 (2013).

Ivanova, E. et al. Guided and unguided Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for social anxiety disorder and/or panic disorder provided via the Internet and a smartphone application: A randomized controlled trial. J. Anxiety Disord. 44, 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.09.012 (2016).

Khoramnia, S. et al. The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy for social anxiety disorder: A randomized clinical trial. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 42, 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1590/2237-6089-2019-0003 (2020).

Kocovski, N. L., Fleming, J. E., Hawley, L. L., Huta, V. & Antony, M. M. Mindfulness and acceptance-based group therapy versus traditional cognitive behavioral group therapy for social anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 51, 889–898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2013.10.007 (2013).

Koszycki, D., Benger, M., Shlik, J. & Bradwejn, J. Randomized trial of a meditation-based stress reduction program and cognitive behavior therapy in generalized social anxiety disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 45, 2518–2526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.011 (2007).

Koszycki, D., Guérin, E., DiMillo, J. & Bradwejn, J. Randomized trial of cognitive behaviour group therapy and a mindfulness-based intervention for social anxiety disorder: Preliminary findings. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 28, 200–218. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2502 (2021).

Koszycki, D. et al. Preliminary Investigation of a Mindfulness-Based Intervention for Social Anxiety Disorder That Integrates Compassion Meditation and Mindful Exposure. J. Alternat. Complement. Med. (New York, NY) 22, 363–374. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2015.0108 (2016).

Ninomiya, A. et al. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in patients with anxiety disorders in secondary-care settings: A randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 74, 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12960 (2020).

Piet, J., Hougaard, E., Hecksher, M. S. & Rosenberg, N. K. A randomized pilot study of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and group cognitive-behavioral therapy for young adults with social phobia. Scand. J. Psychol. 51, 403–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00801.x (2010).

Roemer, L., Orsillo, S. M. & Salters-Pedneault, K. Efficacy of an acceptance-based behavior therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: evaluation in a randomized controlled trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 76, 1083–1089. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012720 (2008).

Stefan, S., Cristea, I. A., Szentagotai Tatar, A. & David, D. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for generalized anxiety disorder: Contrasting various CBT approaches in a randomized clinical trial. J. Clin. Psychol. 75, 1188–1202. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22779 (2019).

Vollestad, J., Sivertsen, B. & Nielsen, G. H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for patients with anxiety disorders: Evaluation in a randomized controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 49, 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.01.007 (2011).

randomised controlled trial. Wong, S. Y. et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy v. group psychoeducation for people with generalised anxiety disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry 209, 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.115.166124 (2016).

Hunot, V. et al. “Third wave” cognitive and behavioural therapies versus other psychological therapies for depression. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 20, CD008704. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008704.pub2 (2013).

Schulz, K. F., Altman, D. G., Moher, D. & Group, C. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. PLoS Med. 7, e1000251. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000251 (2010).

Furukawa, T. A. et al. Waiting list may be a nocebo condition in psychotherapy trials: a contribution from network meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 130, 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12275 (2014).

Cuijpers, P., Quero, S., Papola, D., Cristea, I. A. & Karyotaki, E. Care-as-usual control groups across different settings in randomized trials on psychotherapy for adult depression: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 51, 634–644. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291719003581 (2021).

Watts, S. E., Turnell, A., Kladnitski, N., Newby, J. M. & Andrews, G. Treatment-as-usual (TAU) is anything but usual: A meta-analysis of CBT versus TAU for anxiety and depression. J. Affect. Disord. 175, 152–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.025 (2015).

Bandelow, B. et al. Efficacy of treatments for anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 30, 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1097/yic.0000000000000078 (2015).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Holger Cramer was supported by the Erich Rothenfußer Stiftung. Apart from this, the review received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.H. was responsible for the conception and design of the meta-analysis, the collection and analysis of the study data and for drafting the manuscript. P.B. and M.S. participated in the collection and analysis of the study data and critically revised the manuscript. G.D. critically revised the manuscript. H.C. participated in the conception and design of the meta-analysis, the analysis of the study data, and critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Haller, H., Breilmann, P., Schröter, M. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of acceptance- and mindfulness-based interventions for DSM-5 anxiety disorders. Sci Rep 11, 20385 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-99882-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-99882-w

This article is cited by

-

Psychological Outcomes and Mechanisms of Mindfulness-Based Training for Generalised Anxiety Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Current Psychology (2024)

-

The Western origins of mindfulness therapy in ancient Rome

Neurological Sciences (2023)

-

Eine neue Methode körperbasierter Psychotherapie mittels Selbstberührungen: Idiopraxie®

psychopraxis. neuropraxis (2023)

-

Characterizing Nature Videos for an Attention Placebo Control for MBSR: The Development of Nature-Based Stress Reduction (NBSR)

Mindfulness (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.