Abstract

Considering the increased demand and potential of photovoltaic devices in clean, renewable electrical and hi-tech applications, non-fullerene acceptor (NFA) chromophores have gained significant attention. Herein, six novel NFA molecules IBRD1–IBRD6 have been designed by structural modification of the terminal moieties from experimentally synthesized A2-A1-D-A1-A2 architecture IBR for better integration in organic solar cells (OSCs). To exploit the electronic, photophysical and photovoltaic behavior, density functional theory/time dependent-density functional theory (DFT/TD-DFT) computations were performed at M06/6-311G(d,p) functional. The geometry, electrical and optical properties of the designed acceptor molecules were compared with reported IBR architecture. Interestingly, a reduction in bandgap (2.528–2.126 eV), with a broader absorption spectrum, was studied in IBR derivatives (2.734 eV). Additionally, frontier molecular orbital findings revealed an excellent transfer of charge from donor to terminal acceptors and the central indenoindene-core was considered responsible for the charge transfer. Among all the chromophores, IBRD3 manifested the lowest energy gap (2.126 eV) with higher λmax at 734 and 745 nm in gaseous phase and solvent (chloroform), respectively due to the strong electron-withdrawing effect of five end-capped cyano groups present on the terminal acceptor. The transition density matrix map revealed an excellent charge transfer from donor to terminal acceptors. Further, to investigate the charge transfer and open-circuit voltage (Voc), PBDBT donor polymer was blended with acceptor chromophores, and a significant Voc (0.696–1.854 V) was observed. Intriguingly, all compounds exhibited lower reorganization and binding energy with a higher exciton dissociation in an excited state. This investigation indicates that these designed chromophores can serve as excellent electron acceptor molecules in organic solar cells (OSCs) that make them attractive candidates for the development of scalable and inexpensive optoelectronic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

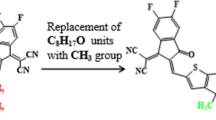

Solar energy is the most poised amongst the renewable sources to avert the climate crisis1,2. Until now Silicon-based solar cells (SCs) have been used frequently due to their low toxicity, thermal stability, and comparatively impressive power conversion efficiency (PCE); but suffer from certain drawbacks, including the high cost of production, heavy weight (20–30 kg m−2), rigidity, as well as defined and unalterable HOMO–LUMO levels3. To overcome these drawbacks, significant research effort has been put into more flexible, lightweight (0.5 kg m−2) organic solar cells (OSCs)4. These show great promise but traditionally suffered from low efficiencies. OSCs are generally bulk heterojunction (BHJ) units where absorption layers blend donor and acceptor molecules. Over the last 2 decades, cell efficiencies have improved from 2 to 18% and it has been possible due to use of fullerenes as electron-accepting moieties5. PCE of OSCs containing fullerene and their derivatives like PC61BM or PC71BM is found to be 11–12%, which is comparatively good electron conduction owing to their deep-lying LUMO levels. But fullerene acceptors suffer from the inability to harvest light as their absorption spectrum is poorly matched to the solar spectrum. This is further complicated by low photostability, diffusion into other layers, and lack of tunability6,7,8,9,10,11. This has given a way to research into non-fullerene acceptors (NFAs), particularly small molecules offering electron affinity tuneability and better-suited absorption spectra to capture sunlight6,7,12,13,14,15. Non-fullerene (NF) solar cells also termed as ‘all polymer’ or fullerene-free solar cells16 are considered as next generation OSCs17. Fused ring electron acceptors (FREAs) is an emergent class that absorbs visible to near-infrared (NIR) very well6,12,18,19,20,21,22,23,24 and possess better PCE values25, high thermic constancy26, and good stability in comparison to other NFAs27. In the last decade, there has been a move to design better photovoltaic materials and fine-tune their optoelectronic characteristics utilizing various FREAs, such as star molecule28, linear geometric molecules29 and X-shaped donor molecule30 etc. FREAs are usually A-D-A type chromophores where donor forms the central core, while electron acceptors act as pendants where they play the role of side end-capped groups which can be modified to tune the optoelectronic properties of investigated compounds13,14,15,31,32,33,34. This arrangement has been shown to be effective to build up highly desirable optoelectronic materials and the prediction of their electronic characteristics prior to synthesis. The properties of NFAs in OSCs inspired us to use recently synthesized A2-A1-D-A1-A2 type efficient NFA as reference chromophore, shortened as IBR synthesized by Zulfiqar et al. with an indenoindene core35 and 3-ethylrodanine end-capped acceptor. The indenoindene core in IBR enhanced the electron transportation due to extended π-electron conjugation. One sp3 carbon bridge and conjugated 14π-electrons in indenoindene allows it for tuning crystallinity, energy levels, absorption and solubility. This core has proven very effective in developing photovoltaic materials36. Li et al. showed that weak electron-withdrawing units play a vital role in tuning charge transport properties and energy level tuning. Thus, we planned to replace 3-ethylrodanine of IBR with different compounds with varying strength of electron removal in combination with indenoindene core to design novel photovoltaic molecules. Further, in the designed compounds, 2-butyloctyl is replaced by a methoxy group taking into account the computational cost. To the best of our information, the photovoltaic investigation of designed compounds (IBRD1–IBRD6) is unreported. Therefore, for the first time, we reported maximum absorption (λmax), frontier molecular orbital (FMOs), density of states (DOS) analysis, open-circuit voltage (Voc), reorganization energies and transition density matrix (TDM) heat maps of IBRD1–IBRD6 chromophores. Above mentioned properties of designed compounds have been compared with IBR to evaluate the performance of end-capped acceptor units. This theoretical insight should offer better design of photovoltaic materials to be used in the OSC applications.

Methods

All the computations for the present work were implemented using Gaussian version 09 software37, and calculations were examined through GaussView version 538. First of all, for optimization of geometrical parameters of IBR, theoretical calculations were performed at various functionals such as B3LYP39, CAM-B3LYP40, M0634, Hartree Fock method (HF)41 and M062X42 with a 6-311G(d,p) basis set. Furthermore, UV–visible investigations for IBR was performed at the aforementioned functionals and basis set in chloroform. At the M06 Level, UV–visible findings exhibited an excellent agreement with experimental values (Fig. 1). After the selection of M06 functional, all the derivatives were optimized at this level of theory. To investigate the structure–property relationship and optoelectronic properties of OSCs, absorption spectra, frontier molecular orbital analysis (FMOs), the density of states (DOS), reorganization energy (RE), transition density matrices (TDM), and open-circuit voltage (Voc) were investigated at M06/6-311g(d,p) level. Moreover, the charge transfer phenomena for the complexes (PBDBT:IBRD3 and PBDBT:IBR-IBRD6) was investigated at M06 and \(\omega\) B97XD with 3-21G basis set. Frequently, the functional (\(\omega\) B97XD) was utilized to explore the dispersion forces43. Subsequently, the charge transformation is significantly observed from donor to acceptor in PBDBT:IBRD3 and PBDBT:IBRD6 at \(\omega\) B97XD/3-21G functional (see Figure S2) as was reported at M06/3-21G level. Various software, including Multiwfn version 3.844, PyMOlyze version 2.045, Avogadro version 1.2.0n46, Gaussview version 5.038 and Chemcraft build 595b47 were used for data analysis.

Graphical representation of comparison between experimentally and calculated UV–Vis results of IBR at four DFT based functionals and Hartree Fock method (HF) in solvent (CHCl3) by utilizing origin 8.5 version (https://www.originlab.com/). All out put files of entitled compounds were accomplished by Gaussian 09 version D.01 (https://gaussian.com/g09citation/).

Results and discussion

In current investigation, IBR, used as a reference molecule, consists on an indenoindene-core that behaves as a donor (D) unit and flanked by A1 (4 methylbenzo[c][1,2,5]thiadiazole) and A2 (3-ethyl-5-methylene-2-thioxothiazolidin-4-one). We substituted the terminal acceptor species (A2) of the IBR with various reported acceptors to design IBRD1–IBRD6 species (Fig. 2) and inspected the acceptor units influence on optoelectronic and photophysical properties of IBR. The optimization with frequency analyses were performed for all the compounds and imaginary frequency was not present in any of the compounds (Tables S22–S28). The optimization with frequency analyses based graphs as well as optimized structures are presented in Figure S1. The absence of any negative frequency in all compounds confirm the accuracy of the optimized molecular structure at true minima. Moreover, their cartesian coordinates are displayed in Tables S1–S7.

Frontier molecular orbital (FMO) investigations

FMO investigation is considered a crucial factor for detecting the photo-electronic properties of OSCs48. It is presumed that according to the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) distribution pattern, the charge transfer in photovoltaic OSCs varies significantly. According to valence band theory, the LUMO and HOMO are considered as conduction and valence bands, respectively. The difference of energy between HOMO/LUMO has been explained as the bandgap (Eg)49,50,51,52,53. The proficiency of OSCs power conversion is fairly reliant on the energy bandgap as there would be a high photovoltaic response of a material with a low Eg and vice versa. Herein, molecular orbital energies and their Eg for entitled compounds are calculated as shown in Table 1.

In IBR, 2.734 eV band gap is studied with − 5.981 and − 3.247 eV energies of HOMO and LUMO, respectively, in a closed relationship with experimental value (2.23 eV)14,35. Interestingly, a reduction in Eg has been examined in designed chromophores. The energies for HOMO are found to be − 6.030, − 6.427, − 6.531, − 6.155, − 6.154, and − 6.141 eV, respectively, for IBRD1–IBRD6, while for LUMO are − 3.502, − 4.161, − 4.405, − 3.714, − 3.739 and − 3.664 eV, respectively (Table 1). The energy gap shows a reduction when the terminal acceptor of IBR is modified in IBRD1, where the combined effect of enlargement in resonance along with electron-withdrawing effect of cyano (–CN) group stabilized the chromophore by lowering its bandgap. Furthermore, a decrease in Eg is examined for IBRD2–IBRD3 when the number of electron-withdrawing groups (–CN) increased (Table 1). Consequently, an increase in the energy gap is also examined when the cyano group is replaced by the chloro group in IBRD4, as cyano is more inductive effect than chloro (–CN > Cl)54. The bandgap starts diminishing in IBRD5 than IBRD4 as the number of the electron-withdrawing groups (–Cl) increased (Fig. 2). Contrarily, a larger value of Eg is exhibited by IBRD6, 2.477 eV, as chloro group on terminal acceptor replaced with fluoro (–F) group. This might be due to the resonance effect that may compete with the inductive effect as F and Cl groups are electron donating due to the resonance effect (Cl > F)55. Overall, the reduction in the bandgap with terminal electron-withdrawing groups was found as F > Cl > CN. Among all the chromophores, it is inferred that IBRD3 has a narrow energy gap as it has three cyano groups that powerfully attract the electronic cloud toward themselves and lower the band gap between orbitals. However, the decreasing Eg order of IBR and IBRD1–IBRD6 is IBR > IBRD1 > IBRD6 > IBRD4 > IBRD5 > IBRD2 > IBRD3. Additionally, the dispersion pattern of electron density in LUMO and HOMO on the surface of both IBR and their fabricated molecules are shown in Fig. 3. In IBR the charge density is located all over the chromophore but significantly concentrated over the central indenoindene-core (donor) in HOMO while end-capped acceptor units in LUMO. Similarly, in all designed molecules charge density for HOMO exists over donor (indenoindene) unit and A1 while in LUMO on the terminal acceptors moieties. A relatively lower Eg between orbitals and effective CT from D to terminal A is examined in derivatives than that of reference which indicates them to be efficient materials for solar cells.

Pictorial representation of FMOs for IBR and IBRD1–IBRD6 drawn with the help of Avogadro software, Version 1.2.0. (http://avogadro.cc/). All out put files of entitled compounds were accomplished by Gaussian 09 version D.01 (https://gaussian.com/g09citation/).

Density of state (DOS)

The density of state (DOS) is the number of different states that electrons will occupy at a given energy level. For energy levels, a high DOS value indicates that numerous states are vacant. The DOS zero value exhibits that there are no states available for occupation at any energy level. DOS computations allow the broad distribution of states as a function of energy to be measured and Eg can also be determined56. Thus, DOS helps in the manifestation of evidence discussed in FMOs and percentage influences about HOMO and LUMO charge densities. Herein, to investigate DOS, IBR and IBRD1–IBRD6 are divided into three fragments, i.e., A1, donor, and A2. In DOS spectra, the scattering pattern of the donor is manifested by a blue line, whereas the green and red lines exhibit the scattering pattern of acceptor-1 and acceptor-2, respectively (Fig. 4). The positive values along the x-axis specify LUMO (conduction band), while negative values express the HOMO (valence band), and the distance between conduction and valence band is expressed as a bandgap44,57.

Graphical representation of the density of states (DOS) of studied chromophores drawn by utilizing PyMOlyze 1.1 version (https://sourceforge.net/projects/pymolyze/). All out put files of entitled compounds were accomplished by Gaussian 09 version D.01 (https://gaussian.com/g09citation/).

For IBR, the Acceptor-1 contributes 20.8% to HOMO and 57.3% to LUMO, whereas, Acceptor-2 contributes to HOMO 14.2% and 30.4% to LUMO. Similarly, Donor contributes to HOMO, 65.0%, and LUMO, 12.3% in IBR. The Acceptor-1 contributes 19.4%, 17.7%, 17.6%, 18.8%, 18.5%, and 18.7% to HOMO and 31.5%, 22.1%, 18.9%, 27.8%, 25.4% and 28.4% to LUMO in IBRD1–IBRD6, respectively. Similarly, acceptor-2 contributes 6.7%, 7.4%, 7.5%, 6.7%, 6.2% and 6.3% to HOMO, while 61.4%, 73.0%, 76.7%, 66.1%, 69.4% and 65.5% to LUMO for IBRD1–IBRD6, respectively. In the same way, donor contributes 74.0%, 74.9%, 74.9%, 74.5%, 75.2% and 75.0% to HOMO whereas 7.1%, 4.9%, 4.4%, 6.1, 5.2, and 6.2% to LUMO for IBRD1–IBRD6, accordingly. DOS speculates that various electron-withdrawing acceptor groups are accountable for different scattering patterns of electron densities. Further, these electronic transitions are also responsible for intramolecular charge transfer. Figure 4 shows that in all chromophores for HOMO the highest peak for charge density is observed at the donor part in the range of − 6 to − 6.5 eV while in LUMO, it appears in A2 units at − 4 eV. Hence, these energy ranges are significant and demonstrated that donor and terminal acceptor moieties are mainly responsible to arise HOMO and LUMO, respectively in designed chromophores which also supported the FMO investigation.

UV–visible absorption spectra

The UV–visible absorption properties were determined by utilizing M06/6-311G(d,p) level in chloroform and gaseous phase to elucidate the optical properties of IBR and IBRD1–IBRD6 (Tables 2, 3; S8–S21). In addition, different parameters comprising oscillator strengths (\(f_{os}\)), transition energy, and molecular orbital transitions were investigated.

Donor–acceptor systems with low energy offset and high photoluminescence show improved performance for high-open-circuit-voltage OSCs58,59. Our results exhibit that efficient electron-withdrawing terminal units with a prolonged conjugation lower the bandgap and allowed the IBRD1–IBRD6 molecules to exhibit smaller excitation energies than IBR, with greater absorption spectra in the visible region (Fig. 5). Among all the derivatives of IBR, the lower value of λmax is examined in IBRD1 which then increased in IBRD6 as the introduction of the fluoro group with cyano group on the terminal acceptor unit.These groups enhance the electron-withdrawing effect in IBRD6, which reduced the energy gap between orbitals and hence, lowers excitation energy with a broader absorption band is examined. Further, a larger absorption band is found in IBRD4–IBRD5, where the fluoro groups are replaced with chloro groups. Higher red shift is examined in IBRD2–IBRD3 when chloro groups are replaced with a more electron-withdrawing cyano group which diminished the Eg. The same trend for absorption is examined in chloroform for all entitled chromophores, but interestingly, in solvent larger bathochromic shift is investigated, which may be due to the polarity of the solvent. Among all derivatives, IBRD3 shows the maximum absorption due to the presence of powerful electron-withdrawing five cyano groups on the terminal acceptor. The increasing absorption pattern is in order of IBR < IBRD1 < IBRD6 < IBRD4 < IBRD5 < IBRD2 < IBRD3 which is inversely related with Eg. The generated absorption spectra of IBR and IBRD1–IBR D6 in gaseous chloroform are shown in Fig. 5. The results show that all designed compounds exhibit better optical properties than IBR. It is therefore evident that structural modeling of the parent molecule with strong acceptor units, chromophores with reduced bandgap and broader absorption spectra can lead to the development of appealing OSCs materials.

Absorption spectra of IBR and IBRD1–IBRD6 in the gaseous phase (left) and chloroform solvent (right) made by using origin 8.5 version (https://www.originlab.com/). All out put files of entitled compounds were accomplished by Gaussian 09 version D.01 (https://gaussian.com/g09citation/).

Reorganization energy (RE)

Measuring the reorganization energy (RE) of the compounds is one of the simplest ways to test CT (charge transfer) properties60. The RE factor defines the position of electron mobility and holes as it directly correlates with the mobility of charges. Therefore, if a compound has low RE, it has elevated mobility of electrons and holes or vice versa. By adjusting parameters, fluctuations in reorganization power occur, but these fluctuations are highly dependent on types of two phases such as number of anions and cations. Cationic structure accords with the hole mobility, while anionic structure accords with the movement of electrons from particular ends. RE is partitioned into two phases; one arrangement inside RE and the other with outer RE. Internal reorganizational energy (λint.) is connected with the inner climate of particles and outside reorganizational energy (λext.) should be identified with the outside environment of an atom. As outside climate effect is less relevant in this context so we are excluding outer RE for this manuscript. Charge transfer and reorganization energy have an inverse relation, so if the reorganization energy is low, the system initiates a significant amount of charge transfer61,62,63,64,65. Therefore, reorganization energies \(\lambda_{{\text{e}}}\) and \(\lambda_{h}\) (\(\lambda_{{\text{e}}} =\) RE of electron) and (\(\lambda_{{\text{h}}} =\) RE of hole) are calculated for entitled chromophores with the help of following equations:

Here, \(E_{0}^{ + }\) and \(E_{0}^{ - }\) are RE of the cation and anion, respectively, computed at the optimized state of a neutral compound. \(E_{ + }\) and \(E_{ - }\) are the RE of cation and anion, respectively.

The λe for IBR is calculated to be 0.00882 eV and all derivatives have the higher value of λe except IBRD2 and IBRD3 as shown in Table 4. According to literature, the compounds with higher value of λe exhibited lower rate of charge transfer14,56,57,66. Therefore, the results from Table 4 indicated that higher rate of electron mobility is presented between donor and acceptor units in IBRD2 and IBRD3 among all the studied compounds as they have the lower value of λe. While IBRD1, IBRD5 and IBRD6 have the higher value of electron reorganization energies than reference so expressed lower electron mobility rate than the parent molecule. IBRD4 and reference compound have almost equal electron charge transfer rate as they have comparable values of λe 0.009976 and 0.00882 eV, respectively. Overall decreasing order of λe is IBRD3 > IBRD2 > IBR. > IBRD4 > IBRD5 > IBRD1 > IBRD6. Similarly, λh calculated for reference is lower than all its derivatives which indicates that among all the designed compounds higher rate for hole transportation is present than parent chromophore (see Table 4). The higher value of λh in designed compounds might be due to their higher ionization potential which inhibits the movement of the holes. Overall, a higher value of λh and lower λe is found in all designed IBRD1–IBRD6 molecules, this making them excellent candidates for electron mobility and appealing acceptors for OSCs. Previosuly, heterojunction interface models with nonfullerene acceptors show better light harvesting capability and intramolecular charge transfer properties along with lower burn-in degradation67,68.

Exciton binding energies and transition density matrix analysis

The tool for measuring and evaluating the transmission of the charge of electrons in an excited state is known as transition density matrix (TDM). In an excited state, it supports to explain donor–acceptor unit interactions, electronic excitation, hole-electron localization and delocalization56,69. As a consequence of extremely limited contribution, hydrogen atoms are excluded during calculation. The nature of the transition is shown in TDM diagrams for all investigated molecules in Fig. 6. To calculate the TDM, we made fragments of designed molecules like Donor (central core: D) and Acceptors (end-capped groups: A1, A2) units.

TDM of the IBR and IBD1–IBRD6 at the S1 state drawn with the help of Multiwfn 3.7software (http://sobereva.com/multiwfn/). All out put files of designed compounds were accomplished by Gaussian 09 version D.01 (https://gaussian.com/g09citation/).

In the scattered form, TDM diagrams shows the presence of charge movement. By considering the FMO and DOS analysis, transfer of charge occurs significantly all over the molecule in designed chromophores. This CT brings considerable changes in TDM heat maps. TDM plots exploited that excitations are significantly confined on D (indenoindene) units and then these excitations diagonally extend via A1 and A2 as though electron–hole pair started to build along diagonally without trapping in all investigated molecules. Binding energy (Eb) is another favorable factor that assists in determining the capacity for exciton dissociation, photo-electronic properties, and efficiency of OSCs. The PCE of OSCs and the parting rate of charges depend on the binding energies (Eb). Further, Eb is also linked to energy driving force (∆E). ∆E is the difference of LUMOs of acceptor and donor and it should be greater than 0.3 eV, for effective exciton split and charge transfer at DA interface69,70. The band gap difference of the optical and electrical energies gives the exciton binding energies. By using Eq. (3) we can calculate Eb71.

In Eq. (3) EH–L = the Eg of HOMO/LUMO. Eopt = minimum amount of energy required for the first excitation, attained from S0 to S1.

It is a significant instrument that tests the columbic forces, the interaction between e (electron) and h (hole). There is a direct relationship between Eb and coulombic hole-electron interaction, which has an inverse relation with exciton dissociation in the excited state72. A molecule with low Eb indicates low columbic contact between h and e that triggers high dissociation of arousal in an excited state. The IBR has a higher value of exciton Eb while IBRD3 expressed the lowest value of exciton Eb 0.437 eV along with smaller λe, compared to the reference and other designed compounds indicating the presence of the greater amount of charges, leading to a higher degree of charge separation in the S1 state observed in Table 5. The decreasing Eb order is obtained to be IBR > IBRD1 > IBRD6 > IBRD4 > IBRD5 > IBRD2 > IBRD3 (Table 5). Because of the low value of Eb, all the derivatives expressed a higher degree of charge partition, hence can act as appealing OSCs material.

Open circuit voltage (V oc)

The term Voc has its significance in organic solar cells73 as OSCs working capability and performance are estimated by examining its Voc. It can be defined as the total quantity of current that can be passed through any optical device74. The Voc is maximum voltage substantially at zero-current levels. Recombination in devices can be achieved with the help of saturation current and light generated current; ultimately, Voc depends on these two factors. Open circuit voltage has an inverse relation with the Eg of donor and acceptor compounds, respectively75,76. A higher value of Voc can be attained if the LUMO level of the acceptor has a higher energy value and the HOMO of the donor have a lower value77. Charber and his coworkers78,79 proposed an equation to calculate the Voc values, the open circuit values of all investigated compounds are calculated by Eq. (4).

where E is the energy and 0.3 is a constant observed from simplifying voltage drop factors60,80 The main idea of Voc is to align the LUMO of designed molecules, including IBR, with the HOMO of a well-acknowledged PBDBT donor. The results obtained are tabulated in Table 6.

The band gap between the orbitals (HOMO/LUMO) of donor/acceptor complexes is found to be 2.154, 1.899, 1.24, 0.996, 1.687, 1.662, and 1.95 eV, respectively, for IBR and IBRD1–IBRD6 (Table 6; Fig. 7). This shows that PBDBT:IBR complex has the highest energy gap value than all other derivative complexes. The Voc of IBR with respect to HOMOPBDBT‒LUMOAcceptor is 1.854 V. Voc of IBRD1–IBRD6 are 1.599, 0.94, 0.696, 1.387, 1.362 and 1.437 V, respectively. All the designed compounds expressed comparable Voc value with respect to reference molecules. The decreasing order of Voc values is: IBR > IBRD1 > IBRD6 > IBRD4 > IBRD5 > IBRD2 > IBRD3. An acceptor species with lower lying LUMO causes greater Voc. A low lying LUMO orbital means that the electron can easily be transferred between the donors to the acceptor unit. In addition, the energy gap between the HOMO and LUMO is also important for the transition of electrons between the donors to the acceptor unit and enhances the PCE. It is clear that in all designed molecules, IBRD1 has higher Voc than other designed molecules, thus possessing better optoelectronic properties. The higher Voc of IBRD1 is due to the higher LUMO and lower HOMO values. The above discussion concludes that all designed acceptor molecules are suitable candidates for use in OSCs due to better optoelectronic properties when aligned with the HOMOPBDBT.

The open-circuit voltage (Voc) of IBR and IBRD1–IBRD6 with respect to the donor PBDBT. All out put files of entitled compounds were accomplished by Gaussian 09 version D.01 (https://gaussian.com/g09citation/).

Charge transfer analysis

To understand the phenomena of charge transfer between our designed acceptor chromophores, we utilized a well-known donor PBDBT polymer. For this purpose, we blend the IBRD3 molecule with PBDBT polymer because of its lowest transition energy, highest λmax, good electron and hole mobility values among IBRD1–IBRD6. Additionally, IBRD6 is also utilized to make a complex with PBDBT polymer as it exhibited a higher value of Voc among all derivatives (Figure S2a, b). The optimization of both complexes (i) PBDBT:IBRD3 and (ii) PBDBT:IBRD6 is implemented at M06 and \(\omega\) B97XD functionals with 3-21G basis set and structures are shown in Figs. 8a and S2(a) for the best transfer of charge; we put our designed chromophores parallel to the donor polymer (Fig. 8b and S2). It is clear from Fig. 8b that the charge density for HOMO is located over the donor PBDBT polymer while LUMO is located over the IBRD3, which indicates that an excellent transfer of electronic cloud from donor PBDBT polymer towards IBRD3 chromophore. The same phenomena are observed for PBDBT:IBRD6 (Figure S2b). This excellent charge transfer revealed that our designed chromophores are suitable non-fullerene solar cell acceptors, which may play a significant role in designing optoelectronic devices.

Optimized geometry of PBDBT:IBRD3 charge transfer between (a) \({\text{HOMO}}_{{{\text{PBDBT}}}}\) and (b) \({\text{LUMO}}_{{{\text{IBRD}}3}}\). at M06/3-21G are made with the help of GaussView 5.0 and Gaussian 09 version D.01 (https://gaussian.com/g09citation/).

Conclusion

A series of indenoindene based A2-A1-D-A1-A2 architecture of novel NF-SMAs (IBRD1–IBRD6) was designed from organic chromophore IBR. These IBRD1–IBRD6 chromophores were obtained by the structural modification of terminal acceptor units. The effect of various A units was examined on photovoltaic properties and a comparable relation is found between parent chromophore and their derivatives. Interestingly, all the derivatives showed a broader spectrum with a smaller bandgap than the parent molecule. FMO, DOS and TDM findings reveals that an effective charge is transfer from donor moiety to acceptor units. Further lower value of λe, indicated higher rate of electron mobility in all designed chromophores.The Voc calculated with respect to PBDBT for IBRD1–IBRD6 was 1.854, 1.599, 0.94, 0.696, 1.387, 1.362, and 1.437 V, respectively. In all newly designed molecules, IBRD3 exhibits the highest optical absorption wavelength (754 nm) with the lowest energy band gap (2.126 eV). All molecules with lower binding energies make the higher exciton dissociation in an excited state, which eventually causes a high transfer rate of charge. These photovoltaic properties suggest that all the newly designed molecules were excellent acceptor candidates for obtaining high PCE in organic solar cells.

References

Kohle, O., Grätzel, M., Meyer, A. F. & Meyer, T. B. The photovoltaic stability of, bis (isothiocyanato) rlutheniurn (II)-bis-2,2′ bipyridine-4,4′-dicarboxylic acid and related sensitizers. Adv. Mater. 9, 904–906 (1997).

Nozik, A. Exciton multiplication and relaxation dynamics in quantum dots: Applications to ultrahigh-efficiency solar photon conversion. Inorg. Chem. 44, 6893–6899 (2005).

Han, G. & Yi, Y. Origin of photocurrent and voltage losses in organic solar cells. Adv. Theory Simul. 2, 1900067. https://doi.org/10.1002/adts.201900067 (2019).

Kupgan, G., Chen, X.-K. & Brédas, J.-L. Molecular packing in the active layers of organic solar cells based on non-fullerene acceptors: Impact of isomerization on charge transport, exciton dissociation, and nonradiative recombination. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 4, 4002–4011. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaem.1c00375 (2021).

Liu, T. & Troisi, A. What makes fullerene acceptors special as electron acceptors in organic solar cells and how to replace them. Adv. Mater. 25, 1038–1041 (2013).

Cheng, P., Li, G., Zhan, X. & Yang, Y. Next-generation organic photovoltaics based on non-fullerene acceptors. Nat. Photonics 12, 131–142 (2018).

Yan, C. et al. Non-fullerene acceptors for organic solar cells. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 18003. https://doi.org/10.1038/natrevmats.2018.3 (2018).

Lin, Y. & Zhan, X. Oligomer molecules for efficient organic photovoltaics. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 175–183 (2016).

Wong, H. C. et al. Morphological stability and performance of polymer–fullerene solar cells under thermal stress: The impact of photoinduced PC60BM oligomerization. ACS Nano 8, 1297–1308 (2014).

Zhang, Y. et al. A simple and effective way of achieving highly efficient and thermally stable bulk-heterojunction polymer solar cells using amorphous fullerene derivatives as electron acceptor. Chem. Mater. 21, 2598–2600 (2009).

Ross, R. B. et al. Endohedral fullerenes for organic photovoltaic devices. Nat. Mater. 8, 208–212. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat2379 (2009).

Hou, J., Inganäs, O., Friend, R. H. & Gao, F. Organic solar cells based on non-fullerene acceptors. Nat. Mater. 17, 119–128 (2018).

Jia, B. et al. Breaking 10% efficiency in semitransparent solar cells with fused-undecacyclic electron acceptor. Chem. Mater. 30, 239–245 (2018).

Kan, B. et al. Small-molecule acceptor based on the heptacyclic benzodi (cyclopentadithiophene) unit for highly efficient nonfullerene organic solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 4929–4934 (2017).

Liu, F. et al. A thieno [3, 4-b] thiophene-based non-fullerene electron acceptor for high-performance bulk-heterojunction organic solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 15523–15526 (2016).

Xia, Y. et al. Inverted all-polymer solar cells based on a quinoxaline–thiophene/naphthalene-diimide polymer blend improved by annealing. J. Mater. Chem. 4, 3835–3843 (2016).

Li, Z. et al. Donor polymer design enables efficient non-fullerene organic solar cells. Nature 7, 1–9 (2016).

Chen, J. D. et al. Polymer solar cells with 90% external quantum efficiency featuring an ideal light-and charge-manipulation layer. Adv. Mater. 30, 1706083 (2018).

Eastham, N. D. et al. Hole-transfer dependence on blend morphology and energy level alignment in polymer: ITIC photovoltaic materials. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704263 (2018).

Sun, C. et al. A low cost and high performance polymer donor material for polymer solar cells. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–10 (2018).

Sun, J. et al. Dithieno [3, 2-b: 2′, 3′-d] pyrrol fused nonfullerene acceptors enabling over 13% efficiency for organic solar cells. Adv. Mater. 30, 1707150 (2018).

Zhao, W. et al. Molecular optimization enables over 13% efficiency in organic solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 7148–7151 (2017).

Zhu, J. et al. Naphthodithiophene-based nonfullerene acceptor for high-performance organic photovoltaics: Effect of extended conjugation. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704713 (2018).

Zhu, J. et al. Alkoxy-induced near-infrared sensitive electron acceptor for high-performance organic solar cells. Chem. Mater. 30, 4150–4156 (2018).

Yang, Y. et al. Side-chain isomerization on an n-type organic semiconductor ITIC acceptor makes 11.77% high efficiency polymer solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 15011–15018 (2016).

Fan, Q. et al. Chlorine substituted 2D-conjugated polymer for high-performance polymer solar cells with 13.1% efficiency via toluene processing. Nano Energy 48, 413–420 (2018).

Baran, D. et al. Reducing the efficiency–stability–cost gap of organic photovoltaics with highly efficient and stable small molecule acceptor ternary solar cells. Nat. Mater. 16, 363–369 (2017).

Ripaud, E., Rousseau, T., Leriche, P. & Roncali, J. J. A. E. M. Unsymmetrical triphenylamine–oligothiophene hybrid conjugated systems as donor materials for high-voltage solution-processed organic solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 1, 540–545 (2011).

Takacs, C. J. et al. Solar cell efficiency, self-assembly, and dipole–dipole interactions of isomorphic narrow-band-gap molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 16597–16606 (2012).

Bibi, S., Li, P. & Zhang, J. J. J. o. M. C. A. X-Shaped donor molecules based on benzo [2, 1-b: 3, 4-b′] dithiophene as organic solar cell materials with PDIs as acceptors. J. Mater. Chem. 1, 13828–13841 (2013).

Dai, S. et al. Fused nonacyclic electron acceptors for efficient polymer solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 1336–1343 (2017).

Xu, S. j. et al. A twisted thieno[3, 4‐b]thiophene‐based electron acceptor featuring a 14‐π‐electron indenoindene core for high‐performance organic photovoltaics. Adv. Mater. 29, 1704510 (2017).

Yao, H. et al. Achieving highly efficient nonfullerene organic solar cells with improved intermolecular interaction and open-circuit voltage. Adv. Mater. 29, 1700254 (2017).

Bryantsev, V. S., Diallo, M. S., Van Duin, A. C. & Goddard, W. A. III. Evaluation of B3LYP, X3LYP, and M06-class density functionals for predicting the binding energies of neutral, protonated, and deprotonated water clusters. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 5, 1016–1026 (2009).

Zulfiqar, A. et al. Thermal-assisted Voc increase in an indenoindene-based non-fullerene solar system. Dyes Pigm. 165, 18–24 (2019).

Xu, S. j. et al. A twisted thieno [3, 4‐b] thiophene‐based electron acceptor featuring a 14‐π‐electron indenoindene core for high‐performance organic photovoltaics. Adv. Mater. 29, 1704510 (2017).

Frisch, M. et al. Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT. Gaussian 09 (2009).

Dennington, R. D., Keith, T. A. & Millam, J. M. GaussView 5.0. 8. Gaussian Inc (2008).

Civalleri, B., Zicovich-Wilson, C. M., Valenzano, L. & Ugliengo, P. B3LYP augmented with an empirical dispersion term (B3LYP-D*) as applied to molecular crystals. CrystEngComm 10, 405–410 (2008).

Yanai, T., Tew, D. P. & Handy, N. C. A new hybrid exchange–correlation functional using the Coulomb-attenuating method (CAM-B3LYP). Chem. Phys. Lett. 393, 51–57 (2004).

Arı, H. & Büyükmumcu, Z. Comparison of DFT functionals for prediction of band gap of conjugated polymers and effect of HF exchange term percentage and basis set on the performance. Comput. Mater. Sci. 138, 70–76 (2017).

Walker, M., Harvey, A. J., Sen, A. & Dessent, C. E. Performance of M06, M06–2X, and M06-HF density functionals for conformationally flexible anionic clusters: M06 functionals perform better than B3LYP for a model system with dispersion and ionic hydrogen-bonding interactions. J. Phys. Chem. A 117, 12590–12600 (2013).

Altalhi, T. A., Ibrahim, M. M., Gobouri, A. A. & El-Sheshtawy, H. S. Exploring non-covalent interactions for metformin-thyroid hormones stabilization: Structure, Hirshfeld atomic charges and solvent effect. J. Mol. Liq. 313, 113590 (2020).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

O'boyle, N. M., Tenderholt, A. L. & Langner, K. M. J. J. O. C. C. Clib: A library for package‐independent computational chemistry algorithms. J. Comput. Chem. 29, 839–845 (2008).

Hanwell, M. D. et al. Avogadro: An advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J. Cheminform. 4, 1–17 (2012).

Zhurko, G. & Zhurko, D. ChemCraft, version 1.6. http://www.chemcraftprog.com (2009).

Khan, M. U. et al. Designing triazatruxene-based donor materials with promising photovoltaic parameters for organic solar cells. RSC Adv. 9, 26402–26418. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9RA03856F (2019).

Khan, M. U. et al. First theoretical probe for efficient enhancement of nonlinear optical properties of quinacridone based compounds through various modifications. Chem. Phys. Lett. 715, 222–230 (2019).

Janjua, M. R. S. A. et al. Effect of π-conjugation spacer (CC) on the first hyperpolarizabilities of polymeric chain containing polyoxometalate cluster as a side-chain pendant: A DFT study. Comput. Theor. Chem. 994, 34–40 (2012).

Khan, M. U. et al. Prediction of second-order nonlinear optical properties of D–π–A compounds containing novel fluorene derivatives: A promising route to giant hyperpolarizabilities. J. Cluster Sci. 30, 415–430 (2019).

Khan, M. U. et al. Quantum chemical designing of indolo [3, 2, 1-jk] carbazole-based dyes for highly efficient nonlinear optical properties. Chem. Phys. Lett. 719, 59–66 (2019).

Adnan, M., Mehboob, M. Y., Hussain, R. & Irshad, Z. In silico designing of efficient C-shape non-fullerene acceptor molecules having quinoid structure with remarkable photovoltaic properties for high-performance organic solar cells. Optik 241, 166839 (2021).

Fujio, M., McIver Jr, R. & Taft, R. W. Effects of the acidities of phenols from specific substituent-solvent interactions. Inherent substituent parameters from gas-phase acidities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 103, 4017–4029 (1981).

Khalid, M., Lodhi, H. M., Khan, M. U. & Imran, M. Structural parameter-modulated nonlinear optical amplitude of acceptor–π–D–π–donor-configured pyrene derivatives: A DFT approach. RSC Adv. 11, 14237–14250 (2021).

Siddique, S. A. et al. Efficient tuning of triphenylamine-based donor materials for high-efficiency organic solar cells. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1191, 113045 (2020).

Ans, M. et al. Designing alkoxy-induced based high performance near infrared sensitive small molecule acceptors for organic solar cells. J. Mol. Liq. 305, 112829 (2020).

Qian, D. et al. Design rules for minimizing voltage losses in high-efficiency organic solar cells. Nat. Mater. 17, 703–709. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-018-0128-z (2018).

Bai, R.-R. et al. Interface configuration effects on excitation, exciton dissociation, and charge recombination in organic photovoltaic heterojunction. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 120, e26103. https://doi.org/10.1002/qua.26103 (2020).

Shehzad, R. A. et al. Designing of benzothiazole based non-fullerene acceptor (NFA) molecules for highly efficient organic solar cells. Computational and Theoretical Chemistry 1181, 112833 (2020).

Mühlbacher, D. et al. High photovoltaic performance of a low-bandgap polymer. Adv. Mater. 18, 2884–2889 (2006).

Zoombelt, A. P., Mathijssen, S. G., Turbiez, M. G., Wienk, M. M. & Janssen, R. A. Small band gap polymers based on diketopyrrolopyrrole. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 2240–2246 (2010).

Lu, J., Zheng, Y. & Zhang, J. Tuning the color of thermally activated delayed fluorescent properties for spiro-acridine derivatives by structural modification of the acceptor fragment: a DFT study. RSC Adv. 5, 18588–18592 (2015).

Kong, H. et al. The influence of electron deficient unit and interdigitated packing shape of new polythiophene derivatives on organic thin-film transistors and photovoltaic cells. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 49, 2886–2898 (2011).

ul Ain, Q. et al. Designing of benzodithiophene acridine based Donor materials with favorable photovoltaic parameters for efficient organic solar cell. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1200, 113238 (2021).

Goszczycki, P., Stadnicka, K., Brela, M. Z., Grolik, J. & Ostrowska, K. Synthesis, crystal structures, and optical properties of the π–π interacting pyrrolo [2, 3-b] quinoxaline derivatives containing 2-thienyl substituent. J. Mol. Struct. 1146, 337–346 (2017).

Bai, R.-R. et al. A comparative study of PffBT4T-2OD/EH-IDTBR and PffBT4T-2OD/PC71BM organic photovoltaic heterojunctions. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 412, 113225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2021.113225 (2021).

Bai, R.-R. et al. Donor halogenation effects on electronic structures and electron process rates of donor/C60 heterojunction interface: a theoretical study on FnZnPc (n = 0, 4, 8, 16) and ClnSubPc (n = 0, 6). J. Phys. Chem. A 123, 4034–4047. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.9b01937 (2019).

Khan, M. U. et al. Designing spirobifullerene core based three‐dimensional cross shape acceptor materials with promising photovoltaic properties for high‐efficiency organic solar cells. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 120, e26377 (2020).

Khalid, A. et al. Designing benzothiadiazole based non-fullerene acceptors with high open circuit voltage and higher LUMO level to increase the efficiency of organic solar cells. Optik 228, 166138 (2021).

Mehboob, M. Y. et al. Designing N-phenylaniline-triazol configured donor materials with promising optoelectronic properties for high-efficiency solar cells. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1186, 112908 (2020).

Mehboob, M. Y. et al. Designing of benzodithiophene core-based small molecular acceptors for efficient non-fullerene organic solar cells. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 244, 118873 (2021).

Irfan, M. et al. Design of donor–acceptor–donor (D–A–D) type small molecule donor materials with efficient photovoltaic parameters. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 117, e25363 (2017).

Tang, S. & Zhang, J. Design of donors with broad absorption regions and suitable frontier molecular orbitals to match typical acceptors via substitution on oligo (thienylenevinylene) toward solar cells. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 1353–1363 (2012).

Liang, Y. et al. For the bright future—Bulk heterojunction polymer solar cells with power conversion efficiency of 7.4%. Adv. Mater.22, E135–E138 (2010).

Ans, M. et al. Designing three-dimensional (3D) non-fullerene small molecule acceptors with efficient photovoltaic parameters. Chem. Select 3, 12797–12804 (2018).

Bai, H. et al. Acceptor–donor–acceptor small molecules based on indacenodithiophene for efficient organic solar cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 6, 8426–8433 (2014).

Scharber, M. C. et al. Design rules for donors in bulk-heterojunction solar cells—Towards 10% energy-conversion efficiency. Adv. Mater. 18, 789–794 (2006).

Mehboob, M. Y. et al. Quantum chemical design of near‐infrared sensitive fused ring electron acceptors containing selenophene as π‐bridge for high‐performance organic solar cells. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 4204 (2021).

Von Hauff, E., Dyakonov, V. & Parisi, J. Study of field effect mobility in PCBM films and P3HT: PCBM blends. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 87, 149–156 (2005).

Acknowledgements

M. Imran expresses appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University Saudi Arabia for funding through research groups program under Grant No. R.G.P. 1/37/42. A.A.C.B. (Grants 2011/07895-8, 2015/01491-3, and 2014/25770-6) is thankful to Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo for financial support. A.A.C.B. (Grant 309715/2017-2) also thanks to the Brazilian National Research Council (CNPq) for financial support and fellowships. This study was also financed in part by the CAPES—Finance Code 001. MSA wants to thank National Horizons Centre at Teesside for providing computation support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K., M., M.I. wrote the original draft and carried out D.F.T. calculations with M.F.R. and M.S.A. A.A.C.B. and M.S.A. edited the manuscript and helped design the study with M.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khalid, M., Momina, Imran, M. et al. Molecular engineering of indenoindene-3-ethylrodanine acceptors with A2-A1-D-A1-A2 architecture for promising fullerene-free organic solar cells. Sci Rep 11, 20320 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-99308-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-99308-7

This article is cited by

-

Chemical Synthesis, Experimental, Molecular Docking and Drug-likeness Studies of Salidroside

Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering (2024)

-

Theoretical studies on donor–acceptor based macrocycles for organic solar cell applications

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

First theoretical framework for highly efficient photovoltaic parameters by structural modification with benzothiophene-incorporated acceptors in dithiophene based chromophores

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Understanding the influence of alkyl-chains and hetero-atom (C, S, O) doped electron-acceptor fullerene-free benzothiazole for application in organic solar cell: first principle perception

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.