Abstract

Syrinx resolution has been associated with an increase in the size of the posterior subarachnoid space (pSAS) after foramen magnum decompression (FMD) for type I Chiari malformation (CM1). The present study investigated the influence of pSAS increase on syrinx resolution and symptom improvement after FMD. 32 patients with CM1 with syrinx were analyzed retrospectively. FMD was performed for the 24 patients with CM1 with syrinx. pSAS areas were measured on sagittal magnetic resonance images. Neurological symptoms were grouped into three clinical categories and scored. The rates of symptom improvement in the CM1 patients with syrinx after FMD was 19.7% ± 12.9%. The mean times to the improvement of neurological symptoms in CM1 patients with syrinx after FMD was 23.4 ± 50.2 months. There were no significant differences between the patients with and without improvement of syrinx after FMD with regard to the age, length of tonsillar herniation, BMI, and preoperative pSAS areas. The rate of increase in the pSAS areas was significantly higher in the group with syrinx improvement within 1 year (p < 0.0001). All patients with a > 50% rate of increase in the pSAS area showed syrinx improvement. Our results suggested that the increasing postoperative pSAS area accelerated the timing of syrinx resolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type I Chiari malformation (CM1) is an anatomical abnormality characterized by cerebellar tonsillar herniation through the foramen magnum1,2. In CM1 patients, the mean position is 13 mm below the foramen magnum with a range from 3 mm below the foramen magnum to 29 mm below3. In general, 5 mm of caudal descent of the tonsil is considered a CM1. Symptoms are thought to originate from an impaired dynamic cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow2,4 and direct compression of the brain stem5,6.

Syringomyelia in CM1 patients has risk of subsequent spinal cord damage. Symptoms of syringomyelia include muscle weakness, loss of reflexes, loss of sensitivity to pain and temperature, headaches, stiffness in your back, shoulders, arms and legs, pain in your neck, arms and back, and scoliosis. The cause of syrinx formation is not yet fully understood. However, previous studies have shown that patients with a smaller posterior fossa volume are more likely to demonstrate abnormalities of the CSF flow at the foramen magnum and have an increased risk of developing syrinx than others7,8,9,10,11,12,13.

The aim of surgery is to relieve central nervous system compression and improve CSF circulation. Although syrinx resolution has been associated with an increase in the posterior subarachnoid space (pSAS) volume after surgery14, the significance of the extent of this volume increase on syrinx resolution remains unclear. In this study, we retrospectively investigated the effect of the extent of pSAS increase on syrinx resolution and symptom improvement after foramen magnum decompression (FMD) in CM1 patients.

Methods

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Patient population

32 patients with CM1 with syrinx (ages, 36.1 ± 15.9 years old; male 7, female 25) were analyzed retrospectively. FMD was performed for 24 patients with CM1 with syrinx. Duraplasty was done for four patients. The timing of surgery was determined by a shared decision-making process involving both physicians and patients. Surgery was recommended for patients who experienced debilitating symptoms. Patients with mild symptoms who requested to reduce neurological symptoms were also treated surgically. Debilitating and mild symptoms indicate Score 1/2 and Score 3/4 in Neurological scores, respectively (Table 1). All human studies were approved by the ethical review board of Osaka University Medical Hospital (No. 17098). All patients provided informed consent prior to inclusion in this study.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the FMD patients with syrinx. We divided the FMD patients with syrinx according to the time of syringomyelia improvement: those who showed improvement within the first postoperative year were classified as having early improvement, and those whose condition improved later were classified as having late improvement. We also divided the FMD patients with syrinx according to the timing of symptom improvement: those who showed improvement within the first postoperative year were classified as having early improvement, and those who improved later were classified as having late improvement.

Radiological assessments

All patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervicothoracic spine and brain. All patients had one or more syrinxes on preoperative MRI. The diagnosis of CM1 was made based on MRI findings and defined as tonsillar herniation at least 5 mm below the level of the foramen magnum. Follow-up MRI was performed every 6 to 12 months.

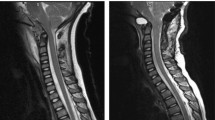

We measured the area of the pSAS between the cerebellar tonsils and C2 in the midline sagittal image on T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) before surgery, immediately after surgery, and at follow-up. The sagittal slice position and orientation were adjusted so that the slice plane was perpendicular to the cervical vertebral body in anterior–posterior axis and left–right axis. The mid-sagittal slice was selected from multiplanar (axial, coronal, sagittal) images. The pSAS area was obtained using manual delineation with the Image J software program15. Two examiners measured the pSAS area. We calculated the inter-rater reliability for the pSAS measurements. ICC2Ck was 0.995. pSAS was enlarged sequentially over time after FMD (Fig. 1). The ratios of the pSAS area immediately after surgery and at follow-up to the preoperative pSAS area were calculated. The percentage increase in pSAS area was calculated by dividing the difference between the pre- and postoperative values by the preoperative value. Syrinx resolution was defined as a decreased syrinx area on midline sagittal images of T2WI. The maximum syrinx/spinal cord length ratio and overall syrinx length were also measured to assess syrinx resolution after FMD. A 20% reduction in the syrinx/cord ratio or overall length at the last follow-up was defined as syrinx resolution.

pSAS was defined as the area between the dura mater and spinal cord from the foramen magnum to C2 on a midline sagittal image on T2-weighted imaging. The yellow line represents the outline of the pSAS. Representative MRI image with syrinx improvement. Right, preoperative images; Middle, postoperative images; Left, images at final follow-up.

Neurological assessments

Symptoms and clinical examination results were obtained from the medical records. A neurological score was given to each patient according to a previously described scoring system (Table 1)16. Symptoms were grouped into three clinical categories: pain, sensory disturbance, and motor disturbance. Clinical data were collected at the initial, perioperative, and follow-up examinations. The percentage increase in the improvement of the neurological score was calculated by dividing the difference between the pre- and postoperative values by the preoperative value.

Surgical procedure

A midline skin incision was made extending from just below the inion to the spinous process of the C2 vertebra. We performed exposure of the occipital bone, including defining the borders of the foramen magnum. We then dissected the posterior arch of the C1 vertebra in a subperiosteal fashion. Suboccipital craniectomy with C1 laminectomy was performed with a high speed drill or craniotome and rongeurs in all patients to achieve wide decompression of the cerebellar hemispheres, midline structures, brainstem, and spinal cord. The width and height of the bony opening was 25 to 30 mm. For posterior fossa decompression without duraplasty (PFD), the atlanto-occipital ligament was divided, and the underlying outer dura leaflet was incised and resected. For posterior fossa decompression with duraplasty (PFDD), opening dura was performed in a caudal to rostral fashion. Cranial dura has 2 layers. Dural sinuses lie between these 2 layers. There were no venous structures at the level of the C1. Dural opening proceeded rostrally, maintaining hemostasis by applying bipolar electrocautery or by Weck clips or suture on each side. Arachnoid opening was performed sharply. Using Weck clips or suture to affix the arachnoid to the cut dural edge. Care was taken to avoid contamination of the subarachnoid space with blood. Y-shaped duraplasty was performed with a Gore-Tex® dura substitute (W.L. Gore & Associates Inc., Flagstaff, AZ, USA). The water tight closure was performed with fibulin glue in all patients to guard against potential CSF leakage not noted intraoperatively. No patient developed meningitis, CSF leakage, or wound infection.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using the XLSTAT software program (Addinsoft Inc., NY, USA). Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test was used to compare continuous variables between two groups. For comparisons among multiple groups, data were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test along with Dunn's post hoc test. The values were presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

IRB approval

Ethical review board approval was obtained.

Results

32 patients with CM1 with syrinx was (ages, 36.1 ± 15.9 years old; male 7, female 25) were analyzed retrospectively. The length of tonsillar herniation and preoperative pSAS areas in the CM1 patients with syrinx was 10.5 ± 4.3 (mm) and 81.2 ± 76.2 (mm2), respectively. FMD was performed for 24 patients with CM1 with syrinx (ages, 33.6 ± 16.2 years old; male 5, female 19). The length of tonsillar herniation and preoperative pSAS areas in the FMD patients was 11.2 ± 4.2 (mm) and 49.2 ± 35.8 (mm2), respectively. The rates of symptom improvement in the CM1 patients with syrinx after FMD was 19.7% ± 12.9%. The mean times to the improvement of neurological symptoms in CM1 patients with syrinx after FMD was 23.4 ± 50.2 months. The rates of increase in the pSAS areas in CM1 patients with syrinx after FMD was 169.6% ± 383.4%.

Table 2 shows the characteristics in the CM1 patients with syrinx after FMD. Among CM1 patients with syrinx after FMD, 18 showed improvement in syrinx, while 6 did not. Four cases underwent PFDD. The ages of the patients with and without improvement of syrinx after FMD were 35.1 ± 13.5 years and 29.1 ± 23.5 years, respectively (p = 0.525). The lengths of tonsillar herniation in patients and without improvement of syrinx after FMD were 11.0 ± 4.2 mm, and 11.8 ± 4.6 mm, respectively (p = 0.733). The BMI in patients with and without improvement of syrinx after FMD were 23.7 ± 4.3, and 19.7 ± 3.9, respectively (p = 0.071). The preoperative pSAS areas in patients with and without improvement of syrinx after FMD were 40.1 ± 18.4 mm2, and 52.2 ± 40.0 mm2, respectively (p = 0.626). There were no significant differences between the patients with and without improvement of syrinx after FMD with regard to the age, length of tonsillar herniation, BMI, and preoperative pSAS areas.

In CM1 patients with syrinx, the mean time to the improvement of syrinx was 42.1 ± 50.4 months after FMD. The pre- and postoperative pSAS areas were 49.2 ± 35.9 and 95.3 ± 76.7 (mm2), respectively. CM1 patients in the group with syrinx improvement was significantly higher rate of increase in the pSAS areas after FMD (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the rate of increase in the pSAS areas after FMD was also significantly higher in the group with syrinx improvement within 1 year compared with the group with improvement after 1 year (Fig. 2B). Although there was no correlation between the rate of increase in the pSAS areas after FMD and the timing of syrinx resolution (R2 = 0.081), all patients with a > 50% rate of increase in the pSAS area after FMD showed syrinx improvement (Fig. 3). However, syrinx improvement was limited to 40% among patients with a < 50% rate of increase in the pSAS area. These findings suggest that the increasing postoperative pSAS area accelerated the timing of syrinx resolution in CM1 patients with syrinx.

The rate of increase in the pSAS area after FMD. (A) CM1 patients in the group with syrinx improvement was significantly higher rate of increase in the pSAS areas after FMD. (B) the rate of increase in the pSAS areas after FMD was significantly higher in the group with syrinx improvement within 1 year compared with the group with improvement after 1 year. Imp + : syrinx improvement positive, Imp-: syrinx improvement negative.

Scatter plot showing the time to syrinx resolution. The vertical axis is the rate of increase in the pSAS area after FMD. The horizontal axis is the duration until syrinx improvement. Points over 250% on the vertical axis were not presented. White and black circles indicate syrinx improvement and no improvement, respectively. The dashed line indicates a 50% rate of increase in the pSAS area.

Discussion

FMD re-establishes the CSF flow pathway and resolves syringomyelia15. Patients with a crowded posterior fossa are more likely to experience syrinx formation than those without obvious posterior fossa crowdedness17. Sahuquillo et. al stated that enlargement of the cisterna magna is critical to clinical improvement18. In the present study, CM1 patients with improvement of syrinx showed a marked rate of increase in the pSAS area after FMD. All patients a > 50% rate of increase in the pSAS area after FMD showed syrinx improvement. Thus, syrinx resolution can be expected in cases with a postoperative pSAS area > 1.5 times the preoperative pSAS area. Furthermore, the rate of increase in the pSAS area after FMD was significantly higher in the group with symptom improvement within 1 year than in the group with improvement after 1 year. These findings suggest that the increase in the postoperative pSAS area accelerated the timing of syrinx resolution.

In CM1 patients with syrinx, the pre-operative pain, sensory disturbance, and motor disturbance scores were 3.0 ± 1.1, 3.4 ± 1.2, and 4.6 ± 0.6, respectively, and the respective postoperative scores were 4.0 ± 0.8, 4.2 ± 0.8, and 4.8 ± 0.3. The postoperative scores significantly improved for pain and sensory disturbance (p = 0.0019 and 0.0059, respectively) but not motor disturbance (p = 0.1636). The pre- and postoperative neurological scores was 11.1 ± 1.6 and 13.1 ± 1.3, respectively (p = 0.00002). There was no correlation between the rate of increase in the symptoms after FMD and the timing of improvement in the symptoms after FMD (R2 = 0.311) or between the rate of increase in the pSAS areas after FMD and the rate of increase in the symptoms after FMD (R2 = 0.049).

FMD patients improved symptoms and syrinx19,20. There is debate regarding the risks and benefits of PFD versus PFDD. Meta-analysis shows no convincing evidence that one method is superior over the other21. Another meta-analysis presented that PFD is a safe and effective surgical procedure with comparable outcomes and fewer complications compared to PFDD22. However, it has been reported that PFDD can be an optimal surgical strategy because of its higher clinical improvement and lower recurrence rate in the patients with syringomyelia23. Furthermore, good symptom control has been achieved despite radiographic failure24. Therefore, there is little to choose between PFD and PFDD, establishing post-surgical morphometric standards may lead to select the effective and safe surgical procedure.

Our study is limited by its retrospective design and reliance on imaging interpretation, which inherently lends itself to internal bias. In addition, we analyzed only single sagittal slices; the evaluation of multiple slices may have been more accurate. Other limitations include the selection bias inherent to noncontrolled surgical studies.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that the increase in the postoperative pSAS area accelerated the timing of syrinx resolution However, the study is limited by its retrospective and observational design. Further investigations are needed to better understand how best to treat CM1 in patients with syringomyelia.

References

Alperin, N. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-based measures predictive of short-term surgical outcome in patients with Chiari malformation type I: A pilot study. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 26, 28–38 (2017).

Ventureyra, E. C., Aziz, H. A. & Vassilyadi, M. The role of cine flow MRI in children with Chiari I malformation. Childs Nerv. Syst. 19, 109–113 (2003).

Barkovich, A. J., Wippold, F. J., Sherman, J. L. & Citrin, C. M. Significance of cerebellar tonsillar position on MR. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 7(5), 795–799 (1986).

Limonadi, F. M. & Selden, N. R. Dura-splitting decompression of the craniocervical junction: Reduced operative time, hospital stay, and cost with equivalent early outcome. J. Neurosurg. 101, 184–188 (2004).

Litvack, Z. N., Lindsay, R. A. & Selden, N. R. Dura splitting decompression for Chiari I malformation in pediatric patients: Clinical outcomes, healthcare costs, and resource utilization. Neurosurgery 72, 922–929 (2013).

Whitney, N., Sun, H., Pollock, J. M. & Ross, D. A. The human foramen magnum—Normal anatomy of the cisterna magna in adults. Neuroradiology 55, 1333–1339 (2013).

Atkinson, J. L., Kokmen, E. & Miller, G. M. Evidence of posterior fossa hypoplasia in the familial variant of adult Chiari I malformation: case report. Neurosurgery 42, 401–404 (1998).

Milhorat, T. H. et al. Chiari I malformation redefined: Clinical and radiographic findings for 364 symptomatic patients. Neurosurgery 44, 1005–1017 (1999).

Nishikawa, M., Sakamoto, H., Hakuba, A., Nakanishi, N. & Inoue, Y. Pathogenesis of Chiari malformation: a morphometric study of the posterior cranial fossa. J. Neurosurg. 86, 40–47 (1997).

Nyland, H. & Krogness, K. G. Size of posterior fossa in Chiari type 1 malformation in adults. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 40, 233–242 (1978).

Pinna, G., Alessandrini, F., Alfieri, A., Rossi, M. & Bricolo, A. Cerebrospinal fluid flow dynamics study in Chiari I malformation: implications for syrinx formation. Neurosurg. Focus. 8, 1–8 (2000).

Støverud, K. H., Langtangen, H. P., Ringstad, G. A., Eide, P. K. & Mardal, K. A. Computational investigation of cerebrospinal fluid dynamics in the posterior cranial fossa and cervical subarachnoid space in patients with Chiari I malformation. PLoS ONE 11, e0162938 (2016).

Stovner, L. J., Bergan, U., Nilsen, G. & Sjaastad, O. Posterior cranial fossa dimensions in the Chiari I malformation: Relation to pathogenesis and clinical presentation. Neuroradiology 35, 113–118 (1993).

Taylor, D. G. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid area and syringogenesis in Chiari malformation type I. J. Neurosurg. 21, 1–6 (2020).

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675 (2012).

Klekamp, J. & Samii, M. Introduction of a score system for the clinical evaluation of patients with spinal processes. Acta Neurochir. (Wien). 123, 221–223 (1993).

Ishikawa, M., Kikuchi, H., Fujisawa, I. & Yonekawa, Y. Tonsillar herniation on magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosurgery 22, 77–81 (1988).

Sahuquillo, J. et al. Posterior fossa reconstruction: a surgical technique for the treatment of Chiari I malformation and Chiari I/syringomyelia complex—Preliminary results and magnetic resonance imaging quantitative assessment of hindbrain migration. Neurosurgery 35, 874–884 (1994).

Papaker, M. G. et al. Clinical and radiological evaluation of treated Chiari I adult patients: retrospective study from two neurosurgical centers. Neurosurg. Rev. 44, 2261–2276 (2021).

Hida, K., Iwasaki, Y., Koyanagi, I., Sawamura, Y. & Abe, H. Surgical indication and results of foramen magnum decompression versus syringosubarachnoid shunting for syringomyelia associated with Chiari I malformation. Neurosurgery 37, 673–678 (1995).

Durham, S. R. & Fjeld-Olenec, K. Comparison of posterior fossa decompression with and without duraplasty for the surgical treatment of Chiari malformation Type I in pediatric patients: a meta-analysis. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2, 42–49 (2008).

Tavallaii, A. et al. Outcomes of dura-splitting technique compared to conventional duraplasty technique in the treatment of adult Chiari I malformation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg. Rev. 44, 1313–1329 (2021).

Lin, W. et al. Comparison of results between posterior fossa decompression with and without duraplasty for the surgical treatment of chiari malformation type I: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 110, 460-474.e5 (2018).

Tosi, U. et al. Persistent syringomyelia after posterior fossa decompression for chiari malformation. World Neurosurg. 136, 454-461.e1 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. T. Moriwaki.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.O., K.I., T.T., S.F., and S.K. performed surgery. Y.O., T.T., and S.F. retrospectively collected and analyzed data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ohnishi, Y., Fujiwara, S., Takenaka, T. et al. An increase in the posterior subarachnoid space accelerates the timing of syrinx resolution after foramen magnum decompression of type I Chiari malformation. Sci Rep 11, 19152 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-98546-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-98546-z

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.