Abstract

Stress is one of the major causes of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which is well-known for perturbing the microbiome and exacerbating IBS-associated symptoms. However, changes in the gut microbiome and metabolome in response to colorectal distention (CRD), combined with restraint stress (RS) administration, remains unclear. In this study, CRD and RS stress were used to construct an IBS rat model. The 16S rRNA gene sequencing was used to characterize the microbiota in ileocecal contents. UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS assay was used to characterize the metabolome of gut microbiota. As a result, significant gut microbial dysbiosis was observed in stress-induced IBS rats, with the obvious enrichment of three and depletion of 11 bacterial taxa in IBS rats, when compared with those in the control group (q < 0.05). Meanwhile, distinct changes in the fecal metabolic phenotype of stress-induced IBS rats were also found, including five increased and 19 decreased metabolites. Furthermore, phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis were the main metabolic pathways induced by IBS stress. Moreover, the altered gut microbiota had a strong correlation with the changes in metabolism of stress-induced IBS rats. Prevotella bacteria are correlated with the metabolism of 1-Naphthol and Arg.Thr. In conclusion, the gut microbiome, metabolome and their interaction were altered. This may be critical for the development of stress-induced IBS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a highly prevalent and multifactorial functional gastrointestinal disorder, and is characterized by altered bowel habits that lower a patient’s quality of life1. IBS has multiple triggers2,3, such as psychological4 and genetic factors5, bacterial gastroenteritis6, and gut microbiota, which has been studied intensively in recent years7. Researchers have found that stress and stress-related factors could lead to IBS-like symptoms, such as visceral hypersensitivity, dysmotility and altered colonic permeability8,9. The stress-induced rat model has been well used for the basic study of IBS and IBS-related disease.

It is presently well-accepted that the gut microbiota is critical in physiological function, regulating host immunity and metabolism, which is also affected by environmental factors inside and outside of the host10,11. The gut microbiota and metabolites secreted by the microbiota are important components of the intestinal mucosal micro-ecosystem. A growing number of studies have indicated that changes in the intestinal mucosal micro-ecosystem are correlated with the development of IBS12,13,14. However, the altered gut microbiota pattern in IBS conditions remains unclear. In addition, microbial- and host-derived metabolites can regulate many life activities, including cell signal release, energy transfer, intercellular communication, and so on11. Therefore, the functional change of the gut microbiota may be reflected in the intestinal metabolome. Thus, identifying the gut microbiota and metabolites composition, as well as the interrelation between these, may be helpful in understanding the mechanism of IBS.

It was hypothesized that the stress-induced microbial component and function changes create a metabolic environment that favors IBS development. Colorectal distention (CRD) and restraint stress (RS) are usually used for constructing the IBS model15,16. The present study employed the IBS model, 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS-based metabolomics approaches to explore the alterations and correlations of the gut microbiota and metabolic phenotype of the IBS rat model through stress treatment.

Materials and methods

Animals

A total of 20 male Sprague-Dawley rats, which were 6–8 weeks old and weighed approximately 240–260 g, were purchased from the Animal Laboratory of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University. These rats were raised in cages under a temperature-controlled room with a light cycle of 12 h of light and 12 h of darkness, and received ad libitum access to food and water. This animal study was approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, with approval number ZSLL-2016-145; ZSLL-2016-129 (Animal ethics approved by Mr. Wang Dejun in September 2016). All experiments were performed in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. All procedures were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines’ in the manuscript.

IBS model establishment and sample collection

In the present study, rats were randomly divided into two groups: control group (n = 10) and IBS group (n = 10). The IBS model was established, as previously described17. In brief, IBS rats were subjected to 14 days of colorectal distention, and subsequently treated with restraint stress for five days. These experiments were performed between 10:00 a.m. and 12:00 p.m. each day. Rats in control group did not receive the stress treatment (Fig. 1). After the 19-day consecutive treatment, the IBS and control group rats were sacrificed under systemic anesthesia using pentobarbital sodium. Then, the ileocecal contents were immediately collected and fresh frozen at − 80 °C for further microbiome and metabolome analysis.

IBS model evaluation

Visceral hypersensitivity was measured by grading the behavioral response of rats18, and this was evaluated by a blind observer through visual observation of the abdominal withdrawal reflex (AWR)19,20. The AWR for each rat was evaluated for three times by two independent operators. The mean AWR value was taken to eradicate any discrepancies, and used for the following statistical analysis.

Microbiome analysis

The genomic DNA of the gut microbiota was extracted from the ileocecus content using a QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and quantity of DNA were evaluated by Nanodrop 2000 ultraviolet spectrophotometry. The bacterial DNA was amplified using universal primers 343f, 5′-TACGGRAGGCAGCAG-3′ and 798r, 5′-AGGGTATCTAATCCT-3′ by targeting for the V3-V4 hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene21. The reverse primer contained a sample barcode, and both primers contained the Illumina sequencing adapter. Then, the PCR products were purified and quantified, and were used for sequencing on an IlluminaMiseq PE300 platform (Illumina, San Diego, USA) using a 300-bp paired-end sequencing protocol. Quality filtering was performed for the raw paired-end reads using the Trimmomatic software (version v.0.38)22. The paired-end read was assembled using the FLASH software (version v.1.2.8)23.

The optimized sequences were assigned to operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using Uparse (version v.10.0.240), according to a 97% identity cut-off24. The most abundant sequence of each OTU was selected as the representative sequence, subjected to the RDP classifier for taxonomical assignment, and compared with the Greengenes taxa (version 13.8), the NCBI 16S Microbial database (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/db/16SMicrobial.tar.gz), and SILVA databases (version 132)25. OTUs cluster, α-diversity and β-diversity calculation, and rarefaction analysis were performed using the MOTHUR program (version v.1.35.1). The relative abundances of the gut microbiota in the control and IBS groups were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) post hoc test. Then, the microbiota and metabolites were evaluated for the predictive accuracy of IBS by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

The functional capabilities of the gut microbiome were predicted by PICRUSt26. The high-level phenotypes that were present in the microbiome were predicted using BugBase, which is a microbiome analysis tool for determining the relative abundance difference of seven microbial communities. The differences between each group were analyzed using Wilcoxon rank-sum test. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Metabolomic (UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS) analysis

The ileocecus contents sample preparation was processed according to the report of Lv et al.27, with minor modifications. Then, 0.2 g of the ileocecus contents sample was diluted using 1 ml of methanol, mixed for 15 s, and allowed to stand for five minutes. Afterwards, the mixtures were shaken upside-down for 15 min, and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min. The resulting supernatant was filtered and used for the metabolic profiling analysis.

The UHPLC system (1290, Agilent Technologies) was used for the chromatographic separations. A Triple TOF mass spectrometer (MS) was used to acquire the MS/MS spectra during the LC/MS experiment28.

The raw data obtained from the UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS runs were analyzed using XCMS4dda v1.41.0 and XCMS4lipid v1.41.0. Then, the processed data set was exported and analyzed by SIMCA-P (v14.1, Sweden). The normalized data (peak area normalization) was used to perform the OPLS-DA analysis (the data scaling was performed using Pareto scaling [PAR]; and this was validated by sevenfold cross-validation and response permutation testing [RPT]), which was taken to characterize the metabolic perturbation between the control and IBS groups. Student's t test was used to identify metabolites that significantly differed between the two groups. The metabolic pathways of metabolites correlated to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) database were analyzed using MetaboAnalyst (http://www.metaboanalyst.ca).

Statistics analysis

The statistical comparisons were analyzed using SPSS 22.0 statistical software (Chicago, USA). The experimental data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The correlation analysis between two differentially significant variables (16S rRNA and metabolites) was carried out using the Spearman rank correlation test (Spearman’s rank correlation test, p < 0.05, correlation coefficient > 0.6 or < − 0.6).

Ethics approval

This article was approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University (approval number ZSLL-2016-145; ZSLL-2016-129). (Animal ethics approved by Mr. Wang Dejun in September 2016).

Consent to participate

We declare consent to participate.

Consent for publication

We declare consent for publication.

Results

Assessment of the IBS model

The rats in IBS group were subjected to 14 days of colorectal distention and 5 days of restraint stress. After the 19-day stress treatment, the model rats appeared listless and irritable. In addition, shrugged hair and reduced activity were observed. Furthermore, the stools were thin and soft, accompanied by perianal fecal residue. The mean AWR scores of IBS rats were higher, when compared to those of the control rats, at colorectal distention pressures of 20, 40, 60 and 80 mmHg (20 mmHg, P = 0.015; 40 mmHg, P = 0.009; 60 mmHg, P = 0.000; 80 mmHg, P = 0.048; Fig. 2a).

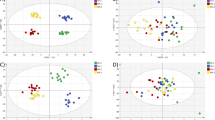

Assessment of the IBS model and the diversity and richness of the gut microbiome between control and stress-induced IBS rats. (a) The abdominal withdrawal reflex (AWR) scores in response to stress were evaluated in the control and IBS groups, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; (b) The microbial diversity characterized by the Shannon index between the control and IBS groups, P < 0.001; (c) The microbial diversity characterized by the Simpson index between the control and IBS groups, P = 0.01; (d) The microbial richness estimated by the Chao1 index between the control and IBS groups, P = 0.79.

The gut microbiome altered in the IBS model

A total of 732,648 reads (with 99.5% distributed in 400–500 bp length) were obtained from 20 samples, and were identified to 6538 OTUs at 97% similarity level. The declines in the species diversity were observed, as characterized by the Shannon Wiener index and Simpson index (Fig. 2b,c). However, no statistically significant difference was observed in mean community richness, as estimated by the Chao1 index (Fig. 2d) between the control and IBS groups. The principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) revealed that the diversity of microbiota did not significantly differ between the control and IBS samples (Supplemental material 1).

The taxonomical analysis indicated that Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria were the major phyla of the gut microbiota in both groups. It is noteworthy that, compared to the control group, the relative abundance of Epsilonbacteraeota was decreased in the IBS group at the phylum level. The 16 s rRNA sequencing indicated that Bacteroides, Helicobacter, Prevotella_9, Prevotellaceae_UCG-001, Oscillibacter and Christensenellaceae_R-7_group were the predominant genera at the genus level in both groups. Furthermore, the microbial composition changes of the ileocecus contents in the IBS group were as follows: Prevotella_9, Collinsella and Prevotellaceae_UCG-001 significantly increased, and Bacteroides, Oscillibacter, Holdemania, Helicobacter, Sellimonas, Butyricicoccus, Lachnospiraceae_ND3007_group, Adlercreutzia, Christensenellaceae_R_7_group, Family_XIII_AD3011_group, and Marvinbryantia significantly decreased (Fig. 3a,b). The ROC curve analysis also revealed that Prevotella_9, Marvinbryantia, Oscillibacter, and Adlercreutzia were the potential biomarkers for separating IBS rats from control rats (Table 1).

(a) The relative abundances in bacterial phylum, class, order, family, genus and species levels in the control (n = 10) and IBS (n = 10) groups, P < 0.05. (b) The dendrogram of the different gut microbiome obtained from the control (n = 10) and IBS (n = 10) groups, the statistical difference is presented in red (P < 0.05). Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) post hoc test.

Furthermore, the KEGG pathway analysis revealed that 27 KEGG pathways in level 2 were significantly decreased in the IBS group, when compared to the control group (Supplemental material 2). In order to avoid the impact of abundance on the predicted metagenomes, Bonferroni adjusted P-values were performed to analyze the KEGG pathways in level 3 with significantly different abundances. Compared with the control group, one KEGG pathway (Arachidonic acid metabolism, P = 0.007) was significantly enriched in the IBS samples, while two KEGG pathways (Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, P = 0.016; Penicillin and cephalosporin biosynthesis, P = 0.023) were significantly decreased in the IBS samples. In addition, the high-level phenotypical difference analysis indicated that the abundance of oxidative stress tolerant bacteria was higher, when compare to that in the IBS group (P = 0.035, Supplemental material 3).

The gut metabolic profiles altered in the IBS model

The metabolic profile difference between control and IBS rats was examined using the OPLS-DA model (Supplemental material 4). A total of 24 differentially relatively abundant metabolites with values of variable importance for projection (VIP) larger than 2.0 were identified between control and IBS rats: tryptamine, l-phenylalanine, d-allose, glycyl-l-leucine, deoxycytidine, 2′-deoxyuridine, deoxyguanosine, tyramine, nicotinamide, 1-methylhistamine, 1-naphthol, dl-3-phenyllactic acid, 5-aminopentanoic acid, betaine aldehyde, 4-hydroxycinnamic acid, benzenamine, N,N-dimethyl, dl-phenylalanine, Val-Ala, inosine, 2′-deoxy, Arg-Thr, .alpha.-CEHC, Ile-Met, Pro-Val, and 1-(9Z-octadecenoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (Table 2). Among these metabolites, five metabolites significantly decreased, while 19 metabolites significantly increased in experimental rats, when compared to normal controls. As indicated by the ROC curve analysis, dl.phenylalanine, dl-3-phenyllactic acid, nicotinamide and 1-naphthol can be used to distinguish IBS rats from controls (Table 1). Furthermore, phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis, pyrimidine metabolism, and the biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids were detected to be involved in the most relevant metabolic pathways influenced by IBS, with impact values of 0.500, 0.024 and 0.013, respectively (Fig. 4).

The pathway analysis of metabolites in the control and IBS groups (bubble diagram). Each bubble represents a metabolic pathway. The abscissa and bubble size indicate the size of the influence factor of the pathway in the topological analysis. The larger the size, the more obvious the influence became. The ordinate of the bubble and bubble color indicate the enrichment extent (negative common logarithm, i.e. − log10 P-value). The deeper the bubble color, the more significant the enrichment of metabolites became.

Correlations between the gut microbiome and metabolome

The Spearman correlation analysis for significantly different metabolites and microbes was performed to obtain the relationships between metabolites and microbes (Fig. 5). As a result, Prevotella_9, which increased by 23.25-fold in IBS rats, was found to be positively correlated with 1-Naphthol, but negatively correlated with Arg-Thr. Similarly, dl-phenylalanine, dl-3-phenyllactic acid and Tyramine were negatively correlated with Sellimonas, Marvinbryantia, Holdemania, Christensenellaceae_R_7_group and Oscillibacter, respectively. In addition, 4-Hydroxycinnamic acid was negatively correlated with Holdemania and Christensenellaceae_R_7_group. Furthermore, 5-Aminopentanoicacid was positively correlated with Sellimonas and Christensenellaceae_R_7_group, while Nicotinamide was negatively correlated with Collinsella. In summary, stress can induce a significant difference in the structure/composition of the gut microbiome, and substantially alter the metabolomic profile.

Discussion

The present study revealed the significant differences in gut microbial community abundance in the levels of phylum, class, order, family, genera and species between IBS and control rats. The metabolic profile was changed in stress-induced IBS rats. In addition, the altered gut microbiota had significant correlations with metabolites. These findings may provide mechanistic insights on IBS pathophysiology in the aspects of gut microbiome and metabolome. Furthermore, these may provide new potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for the treatment of IBS disease, and preventing its progression. A decrease in microbial diversity in the present IBS model was observed through the 16S rRNA gene sequencing of ileocecum contents, indicating that the microbial diversity was affected by stress treatment. Interestingly, microbial diversity was also reported to be decreased in the noxious-stress animal model29 and IBS patients30,31, suggesting that gut microbial diversity is important for preventing IBS development. Furthermore, it was also reported that the number of oxidative stress tolerant bacteria increased in the stress-induced IBS rat model, suggesting that the gut microbiota can modify itself to accommodate stress.

The abundance of certain key taxa and microbial clades substantially differed between the IBS and control groups. At the genus level, Prevotella_9 and Collinsella were significantly over-represented in the stress-induced IBS samples, while Christensenellaceae_R-7_group, Bacteroides, Marvinbryantia, Butyricicoccus, Adlercreutzia, Oscillibacter and Lachnospiraceae_ND3007_group were under-represented. The overabundance of Prevotella in the IBS model was consistent with the results reported by previous studies7,32,33,34. The Prevotella may be involved in inducing visceral hypersensitivity and exacerbating the symptoms of IBS by promoting carbohydrate fermentation and impairing intestinal mucosal immune function35,36. Prevotella overabundance was also correlated to other systemic conditions with high-fat diet, such as obesity37 and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease38. Similarly, the 5.5-fold increase in abundance of the genus Collinsella in IBS rats may have the potential to play a significant role in intestinal gas production, and have a proinflammatory effect, thereby contributing to IBS development39. In addition, the decrease in butyrate-producing bacteria40,41,42,43 in the IBS model, such as Christensenellaceae_R-7_group44, Bacteroides45, Butyricicoccus46, Adlercreutzia47, Marvinbryantia48, Oscillibacter7 and Lachnospiraceae_ND3007_group49, was also reported to be variously associated with IBS in humans, as well as in rat models of visceral pain. Butyrate has been proposed to play a key role in maintaining gut homeostasis and epithelial integrity, since it serves as the main energy source for colonocytes. This can directly inhibit histone deacetylases, and interfere with proinflammatory signals50,51. The enrichment of arachidonic acid metabolism was also observed in the IBS group, which is involved in a classical inflammation signal pathway52. In addition, a recent study conducted by Aguilera-Lizarraga et al.53 on the microbiota of IBS patients with meal-induced abdominal pain also support the notion that inflammation may contribute to the initiation of IBS visceral hypersensitivity, since pro-inflammation-related bacteria were significantly elevated in the IBS groups (Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes).

The enrichment of this pathway in the IBS group may contribute to the development of IBS. The metabolic potential of gut microbes has been shown to modulate the health status of the host11,54. Alterations in the relative abundance of 10 major metabolites were observed, in which three of these (Nicotinamide, Pro.val and Arg.Thr) significantly decreased in the IBS samples, while seven of these (4-Hydroxycinnamic acid, l.Phenylalanine, dl.Phenylalanine, dl-3-Phenyllactic acid, Tryptamine, Tyramine and 1-Naphthol) significantly increased. Nicotinamide is highly concentrated in healthy colons, and can reduce inflammation and carcinogenesis via affecting T-cell differentiation55,56,57. The other two decreased metabolites, Arg.Thr58 and Pro.val59, can participate in the synthesis and decomposition of essential or non-essential amino acids, and contribute to the maintenance of immune stability. The decreased abundance of these three metabolites in the stress-induced IBS rat model indicates that colonic immune instability might be affected. The increased metabolic of dl-3-Phenyllactic acid60 and 4-Hydroxycinnamic acid61,62, which has many pharmacological properties including immune-modulatory, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, may be involved in regulating the imbalance of intestinal immunity. These two isoforms of Phenylalanine, l.Phenylalanine and dl.Phenylalanine have similar physiological efficacy, and these were detected to be highly produced in the stress-induced model, indicating the low bioavailability of metabolites in the intestine of stress rats. These two metabolites were reported to be associated with inflammation63, and were also reported in a previous IBS-related study64. Furthermore, the increased level of Tryptamine and Tyramine was been considered to be involved in contributing to the hypersensitivity in IBS and antioxygenation65,66. In a recent study, tryptamine was significantly elevated in stool samples obtained from IBS-D patients, and this was confirmed to stimulate colonic epithelium fluid secretion67. The 1-Naphthol is considered as the product of benzene and nepthalene biotransformation, which has a strong antioxygenation effect68. More importantly, l.Phenylalanine, dl.Phenylalanine, Tryptamine and Tyramine are essential aromatic amino acids, which are the major nutrient and closely linked to host energy metabolism. The enrichment of these metabolites indicate that the energy metabolism was perturbed by stress. Consequently, the metabolic changes induced by stress in IBS rats might be closely associated with the imbalance of the colonic immune system, intestinal hypersensitivity, increased energy metabolism and adaptive antioxidant capacity.

The changes in gut microbiota and metabolic phenotypes have been widely used to understand the mechanism of disease development69,70. In the present study, the significantly different microbes and metabolites between the IBS and control groups were examined, and the metabolite-microbial relationship was evaluated. Eight metabolites were correlated with at least one of eight bacteria after the correlation analyses. Tyramine, l.Phenylalanine, and dl-3-Phenyllacticacid increased in the IBS group, and were negatively correlated with five butyrate-producing bacteria. Among these, Prevotella_9 and Collinsella were the positively-related bacteria, while the remaining six bacteria (Christensenellaceae_R_7_group, Marvinbryantia, Holdemania, Sellimonas, Oscillibacter, and Helicobacter) were negatively correlated with the metabolites. The 1-Naphthol had a strong correlation with Prevotella_9, which might suggest that the capability of oxidative stress tolerance was enhanced in IBS rats. The anti-inflammatory metabolite Nicotinamide was closely and negatively correlated with Collinsella, suggesting that Nicotinamide production can be inhibited by Collinsella. Thus, these correlation differences may play a role in discovering the relationship between IBS and gut microenvironment variation in the stress model.

In summary, the present study combined 16S rRNA gene sequencing and metabolomics methods to investigate the gut microbiome and metabolic profiles of IBS. The sequencing data revealed that the gut microflora composition was significantly altered in the IBS group, while the metabolomics revealed that a number of metabolites involved in diverse metabolic pathways were perturbed by stress. In addition, the correlation analysis identified that there was an obvious correlation between gut bacteria and metabolites.

Code availability

Accession codes The sequence data have been deposited in the SRA database under accession code PRJNA594853.

References

Lovell, R. M. & Ford, A. C. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: A meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10(7), 712–721 (2012).

Keszthelyi, D., Troost, F. J. & Masclee, A. A. Irritable bowel syndrome: methods, mechanisms, and pathophysiology. Methods to assess visceral hypersensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 303, G141–G154 (2012).

Camilleri, M. Peripheral mechanisms in irritable bowel syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 1626–1635 (2012).

Koloski, N. A. et al. The brain-gut pathway in functional gastrointestinal disorders is bidirectional: A 12-year prospective population-based study. Gut 61, 1284–1290 (2012).

Saito, Y. A., Mitra, N. & Mayer, E. A. Genetic approaches to functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology 138, 1276–1285 (2010).

Rodriguez, L. A. & Ruigomez, A. Increased risk of irritable bowel syndrome after bacterial gastroenteritis: Cohort study. BMJ 318, 565–566 (1999).

Tap, J. et al. Identification of an intestinal microbiota signature associated with severity of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 152(1), 111-123.e8 (2017).

Larauche, M., Kiank, C. & Tache, Y. Corticotropin releasing factor signaling in colon and ileum: Regulation by stress and pathophysiological implications. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 60(Suppl 7), 33–46 (2009).

van den Wijngaard, R. M., Klooker, T. K., de Jonge, W. J. & Boeckxstaens, G. E. Peripheral relays in stress-induced activation of visceral afferents in the gut. Auton. Neuro. sci. 153, 99–105 (2010).

Kau, A. L., Ahern, P. P., Griffin, N. W., Goodman, A. L. & Gordon, J. I. Human nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune system. Nature 474(7351), 327–336 (2011).

Nicholson, J. K. et al. Host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions. Science 336(6086), 1262–1267 (2012).

Pittayanon, R. et al. Gut microbiota in patients with irritable bowel syndrome—A systematic review. Gastroenterology 157(1), 97–108 (2019).

Canakis, A., Haroon, M. & Weber, H. C. Irritable bowel syndrome and gut microbiota. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 27(1), 28–35 (2020).

Mishima, Y. & Ishihara, S. Molecular mechanisms of microbiota-mediated pathology in irritable bowel syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(22), 8664 (2020).

Mao, Q. et al. Chemical profiles and pharmacological activities of Chang-Kang-Fang, a multi-herb Chinese medicinal formula, for treating irritable bowel syndrome. J. Ethnopharmacol. 201, 123–135 (2017).

Garabadu, D., Shah, A., Singh, S. & Krishnamurthy, S. Protective effect of eugenol against restraint stress-induced gastrointestinal dysfunction: Potential use in irritable bowel syndrome. Pharm. Biol. 53(7), 968–974 (2015).

Li, M. et al. Role of dendritic cell-mediated abnormal immune response in visceral hypersensitivity. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 8(8), 13243–13250 (2015).

Distrutti, E., Cipriani, S., Mencarelli, A., Renga, B. & Fiorucci, S. Probiotics VSL#3 protect against development of visceral pain in murine model of irritable bowel syndrome. PLoS ONE 8, e63893 (2013).

Ma, X. P., Tan, L. Y. & Yang, Y. Effect of electro-acupuncture on substance P, its receptor and corticotropin-releasing hormone in rats with irritable bowel syndrome. World J. Gastroenterol. 15(41), 5211–5217 (2009).

Jones, R. C. 3rd. et al. Short-term sensitization of colon mechanoreceptors is associated with long-term hypersensitivity to colon distention in the mouse. Gastroenterology 133, 184–194 (2007).

Nossa, C. W. et al. Design of 16S rRNA gene primers for 454 pyrosequencing of the human foregut microbiome. World J. Gastroenterol. 16(33), 4135–4144 (2010).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30(15), 2114–2120 (2014).

Reyon, D. et al. FLASH assembly of TALENs for high-throughput genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 30(5), 460–465 (2012).

Edgar, R. C. UPARSE: Highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10(10), 996–998 (2013).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596 (2013).

Langille, M. G. et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 31(9), 814–821 (2013).

Lv, L. X. et al. Alterations and correlations of the gut microbiome, metabolism and immunity in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Environ. Microbiol. 18(7), 2272–2286 (2016).

Ivanisevic, J. et al. Arteriovenous blood metabolomics: A readout of intra-tissue metabostasis. Sci. Rep. 5, 12757 (2015).

Liang, X. et al. Bidirectional interactions between indomethacin and the murine intestinal microbiota. Elife 4, e08973 (2015).

Durbán, A. et al. Instability of the faecalmicrobiota in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 86(3), 581–589 (2013).

Mättö, J. et al. Composition and temporal stability of gastrointestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome–a longitudinal study in IBS and control subjects. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 43(2), 213–222 (2005).

Su, T. et al. Altered intestinal microbiota with increased abundance of prevotella is associated with high risk of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2018, 6961783 (2018).

Ley, R. E. Gut microbiota in 2015: Prevotella in the gut: Choose carefully. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 13(2), 69–70 (2016).

Simpson, C. A., Mu, A., Haslam, N., Schwartz, O. S. & Simmons, J. G. Feeling down? A systematic review of the gut microbiota in anxiety/depression and irritable bowel syndrome. J. Affect Disord. 266, 429–446 (2020).

Kovatcheva-Datchary, P. et al. Dietary fiber-induced improvement in glucose metabolism is associated with increased abundance of prevotella. Cell Metab. 22(6), 971–982 (2015).

Staudacher, H. M., Irving, P. M., Lomer, M. C. & Whelan, K. Mechanisms and efficacy of dietary FODMAP restriction in IBS. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11(4), 256–266 (2014).

Zhu, L. et al. Characterization of gut microbiomes in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) patients: a connection between endogenous alcohol and NASH. Hepatology 57(2), 601–609 (2013).

Jiang, W. et al. Dysbiosis gut microbiota associated with inflammation and impaired mucosal immune function in intestine of humans with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci. Rep. 5, 8096 (2015).

Chen, J. et al. An expansion of rare lineage intestinal microbes characterizes rheumatoid arthritis. Genome Med. 8(1), 43 (2016).

Heitkemper, M. M. et al. Stool and urine trefoil factor 3 levels: associations with symptoms, intestinal permeability, and microbial diversity in irritable bowel syndrome. Benef. Microbes. 9(3), 345–355 (2018).

Noor, S. O. et al. Ulcerative colitis and irritable bowel patients exhibit distinct abnormalities of the gut microbiota. BMC Gastroenterol. 10, 134 (2010).

Valeur, J., Småstuen, M. C., Knudsen, T., Lied, G. A. & Røseth, A. G. Exploring gut microbiota composition as an indicator of clinical response to dietary FODMAP restriction in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Dig. Dis. Sci. 63(2), 429–436 (2018).

Zhang, J. et al. Beneficial effect of butyrate-producing Lachnospiraceae on stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity in rats. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 34(8), 1368–1376 (2019).

Hamer, H. M. et al. Review article: the role of butyrate on colonic function. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 27(2), 104–119 (2008).

Zhang, X. et al. Modulation of gut microbiota by berberine and metformin during the treatment of high-fat diet-induced obesity in rats. Sci. Rep. 5, 14405 (2015).

Devriese, S. et al. Reduced mucosa-associated butyricicoccus activity in patients with ulcerative colitis correlates with aberrant claudin-1 expression. J. Crohns. Colitis. 11(2), 229–236 (2017).

Chen, M. et al. Huang-Lian-Jie-Du-decoction ameliorates hyperglycemia and insulin resistant in association with gut microbiota modulation. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2380 (2018).

Wang, J. et al. Alfalfa-containing diets alter luminal microbiota structure and short chain fatty acid sensing in the caecal mucosa of pigs. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 9, 11 (2018).

Zhou, D. et al. Sodium butyrate attenuates high-fat diet-induced steatohepatitis in mice by improving gut microbiota and gastrointestinal barrier. World J. Gastroenterol. 23(1), 60–75 (2017).

Vital, M., Karch, A. & Pieper, D. H. Colonic butyrate-producing communities in humans: An overview using omics data. mSystems. 2(6), e00130-17 (2017).

van der Beek, C. M., Dejong, C. H. C., Troost, F. J., Masclee, A. A. M. & Lenaerts, K. Role of short-chain fatty acids in colonic inflammation, carcinogenesis, and mucosal protection and healing. Nutr. Rev. 75(4), 286–305 (2017).

Hanna, V. S. & Hafez, E. A. A. Synopsis of arachidonic acid metabolism: A review. J. Adv. Res. 11, 23–32 (2018).

Aguilera-Lizarraga, J. et al. Local immune response to food antigens drives meal-induced abdominal pain. Nature 590(7844), 151–156 (2021).

Jones, B. V., Begley, M., Hill, C., Gahan, C. G. & Marchesi, J. R. Functional and comparative metagenomic analysis of bile salt hydrolase activity in the human gut microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105(36), 13580–13585 (2008).

Thorburn, A. N., Macia, L. & Mackay, C. R. Diet, metabolites, and ‘western-lifestyle’ inflammatory diseases. Immunity 40, 833–842 (2014).

Singh, N. et al. Activation of Gpr109a, receptor for niacin and the commensal metabolite butyrate, suppresses colonic inflammation and carcinogenesis. Immunity 40, 128–139 (2014).

Hill, L. J. & Williams, A. C. Meat intake and the dose of vitamin B3-nicotinamide: Cause of the causes of disease transitions, health divides, and health futures?. Int. J. Tryptophan. Res. 10, 1178646917704662 (2017).

Bensing, B. A. et al. Structural basis for sialoglycan binding by the Streptococcus sanguinis SrpA adhesin. J. Biol. Chem. 291(14), 7230–7240 (2016).

Kruszewska, H., Zareba, T. & Tyski, S. Examination of antimicrobial activity of selected non-antibiotic medicinal preparations. Acta Pol. Pharm. 69(6), 1368–1371 (2012).

Mu, W., Yu, S., Zhu, L., Zhang, T. & Jiang, B. Recent research on 3-phenyllactic acid, a broad-spectrum antimicrobial compound. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 95(5), 1155–1163 (2012).

Neog, M. K., Joshua Pragasam, S., Krishnan, M. & Rasool, M. p-Coumaric acid, a dietary polyphenol ameliorates inflammation and curtails cartilage and bone erosion in the rheumatoid arthritis rat model. BioFactors 43(5), 698–717 (2017).

Ko, J. W. et al. 4-Hydroxycinnamic acid suppresses airway inflammation and mucus hypersecretion in allergic asthma induced by ovalbumin challenge. Phytother Res. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6553 (2019) (Epub ahead of print).

Klassen, P., Fürst, P., Schulz, C., Mazariegos, M. & Solomons, N. W. Plasma free amino acid concentrations in healthy Guatemalan adults and in patients with classic dengue. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 73(3), 647–652 (2001).

Yu, L. M., Zhao, K. J., Wang, S. S., Wang, X. & Lu, B. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry based metabolomic study in a murine model of irritable bowel syndrome. World J. Gastroenterol. 24(8), 894–904 (2018).

Bhattarai, Y. et al. Gut microbiota-produced tryptamine activates an epithelial G-protein-coupled receptor to increase colonic secretion. Cell Host. Microbe. 23(6), 775-785.e5 (2018).

Zar, S., Kumar, D. & Benson, M. J. Food hypersensitivity and irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment. PharmacolTher. 15(4), 439–449 (2001).

Mars, R. A. T. et al. Longitudinal multi-omics reveals subset-specific mechanisms underlying irritable bowel syndrome. Cell 183(4), 1137–1140 (2020).

Eastmond, D. A., French, R. C., Ross, D. & Smith, M. T. Metabolic activation of 1-naphthol and phenol by a simple superoxide-generating system and human leukocytes. Chem. Biol. Interact. 63(1), 47–62 (1987).

Lu, K. et al. Arsenic exposure perturbs the gut microbiome and its metabolic profile in mice: An integrated metagenomics and metabolomics analysis. Environ. Health Perspect. 122(3), 284–291 (2014).

Arrieta, M. C. et al. Early infancy microbial and metabolic alterations affect risk of childhood asthma. Sci. Transl. Med. 7(307), 307ra152 (2015).

Acknowledgements

There are no acknowledgments to report.

Funding

This study was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant no. 81770535) and Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LQ21H030001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.L. designed and supervised the study; Y.H., F.C., and H.Y. conducted the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, Y., Chen, F., Ye, H. et al. Integrative analysis of the gut microbiome and metabolome in a rat model with stress induced irritable bowel syndrome. Sci Rep 11, 17596 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97083-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97083-z

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.